Abstract

Purpose

We investigated whether social health mitigates the association between weight perception and anxiety and depression 1 year later in a large sample of Canadian youth in a prospective, gender-specific analysis.

Methods

We used 2 years of linked survey data from 20,485 grade 9–11 students who participated in wave 6 (2017/18) and 7 (2018/19) of the COMPASS study. Mental health outcomes included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder—7 item (GAD-7) scale and the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Revised (CESD-10-R). Social health encompassed students’ perceived relationships with friends, family, teachers, and within schools. Multilevel, prospective, linear models regressed mental health (at wave 7) on social health (at wave 6) and weight perception (at wave 6) while controlling for weight status, ethnicity, and grade (at wave 6). Interaction terms were used to test social health factors as moderators in the association between weight perception and mental health.

Results

Overweight perceptions were associated with higher anxiety and depression scores among youth; this was more pronounced among females. Social health was associated with lower anxiety and depression scores. Among females only, an overweight perception had the highest predicted scores for significant depressive symptoms. Among males only, underweight perceptions were associated with higher anxiety scores. No social health factors had moderating effects in females, and only two interactions were significant among males: feeling safe at school had protective associations with anxiety scores among those with underweight perceptions while those with overweight perceptions had higher depression scores when they reported rewarding social relationships.

Conclusion

Overweight perceptions in all youth, and underweight perceptions in males, predicted anxiety and depression symptoms 1 year later. The role of social health should not be discounted as a means of preventing anxiety and depression in youth, although this study suggests it is not sufficient to protect against adverse associations with overweight perceptions for all youth, and underweight perceptions for males.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A perception of overweight is associated with a myriad of negative physical and mental health outcomes including: headaches, psychological distress, anxiety, depression, suicidality, and weight gain, regardless of objective weight status [1,2,3,4,5]. These findings are consistent across age-groups and evident in cross-sectional and prospective studies [3, 4, 6]. Focusing on adolescence is particularly important as a key period for the onset of anxiety and depression, with symptoms persisting with age [7, 8], and heightened attention to the body’s appearance, peer acceptance, and social norms.

Among youth, gender differences exist in the psychosocial consequences of having overweight; the effects appear more pronounced among female youth relative to their male counterparts [9]. Stradmeijer et al. [10] reported that lower self-esteem was associated with overweight among Dutch female youth only. The association may be a vicious cycle as low-esteem was also predictive of a perception of overweight among female youth in a US representative sample [11]. In studies from China and the USA, an overweight perception was associated with a higher risk of depressive symptoms and suicide ideation in female adolescents, while no association was reported among males [12, 13]. However, a Korean study reported that an overweight perception was associated with unhealthy weight control behaviours and suicide ideation among females and males [6]. Similarly, in a cross-sectional study of Canadian adolescents, both overweight and underweight perceptions were associated with higher depression and anxiety symptoms [5]. These studies emphasize that gender-specific analyses are required when investigating associations between weight perception and mental health among youth.

The relationship between an individual’s perception of overweight and their mental health may be partially explained via the mediating role of weight bias [4]. Weight bias encompasses objective experiences, such as social rejection (e.g., via media, social exclusion and teasing), and can be internalized [4, 9]. Internalizing societal weight bias is associated with psychological distress, less heath promoting behaviours, poorer self-esteem, and lower cognitive and physical abilities [9, 11, 14].

Few studies have assessed whether social health contributes to links between weight perception and mental health among youth. Social health refers to an individual’s perceptions of key relationships in their lives, e.g., whether they perceive them to be rewarding, supportive, safe, and treated fairly and with respect. These include interactions with peers, family, teachers, school belonging, as well as understanding the quality of relationships, i.e., the extent to which they are (1) rewarding and supportive relationships or (2) might be harmful (e.g., youth victimized by bullying, or family disharmony). The social cognitive theory stipulates that cognitive factors are influenced by a person’s behaviour as well as their environmental factors (e.g., social health), and that these three factors are interrelated [15].

Two US studies found support that social health moderated the association between weight perception and mental health among youth, while a study from China did not [16,17,18]. In a prospective analysis among US youth, Rawana [16] found that an overweight perception and a lack of perceived support (from parents, peers, and schools) significantly predicted depressive symptoms 1 year later. Another US study found that youth with an overweight perception were the group with the highest prevalence of mental distress and the lowest level of protective social health [17]. The same study found that social health (i.e., perceptions of parent, friend, and school connectedness, and social competency) was protective against mental distress among all youth [17]. Finally, a study among Chinese adolescents did not find an association between objective or perceived weight status, psychological functioning and the following social health factors: perceived availability of social support, perceived peer isolation, family disharmony, trouble with teachers and school connectedness [18]. Thus, evidence on the role of social health in the association between weight perception and anxiety and depression is mixed and may differ by gender.

The purpose of this study was to assess the extent to which weight perceptions are associated with anxiety and depression in a large sample of Canadian youth, and to evaluate whether social health (i.e., relationships with peers, family, and teachers, school belonging, and rewarding and supportive relationships) moderates this association prospectively in gender-specific analyses. We hypothesize that perceptions of overweight will be associated with greater anxiety and depression symptoms, with stronger associations in females than males, and that higher social health with provide protective effects in all youth.

Methods

Data source

The ‘Cannabis, Obesity, Mental health, Physical activity, Alcohol, Smoking, and Sedentary behaviour’ (COMPASS) Study is a multi-faceted, ongoing longitudinal study that aims to improve youth prevention research and practice. Data were collected once annually from full school samples via a self-report questionnaire completed during class time. COMPASS uses a convenience sample of secondary schools and boards based on permitted use of active-information passive-consent protocols, which are critical to collecting robust youth data, particularly on sensitive areas such as mental health [19, 20]. All students attending participating schools are eligible to participate. Non-response primarily resulted due to student absenteeism or spare study periods during data collection. Additional details on COMPASS can be found in print [21] or online (www.compass.uwaterloo.ca).

Sample

This study used 2-year linked student data from COMPASS waves 6 (2017/2018) and 7 (2018/2019); these represent the most recent full waves of available data collected before the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and since the full inception of the mental health components of COMPASS in wave 6. Wave 6 included 66,434 students from 122 schools in Ontario [31, 654 students, 61 schools], Alberta (3243 students, 8 schools), British Columbia (12,523 students, 16 schools), and Quebec (19,014 students, 37 schools). In wave 7, 74,501 students completed the student questionnaire from 136 schools in Ontario (30,675 students, 61 schools), Alberta (3301 students, 8 schools), British Columbia (10,402 students, 15 schools), and Quebec (30,123 students, 52 schools). The linked sample included 23,306 grade 9–11 students from 114 schools successfully linked across baseline (wave 6) and follow-up (wave 7) in Ontario (13,521 students, 59 schools), Alberta (1412 students, 8 schools), British Columbia (3902 students, 14 schools), and Quebec (4471 students, 33 schools). The linked sample only included students who were in grades 9–11, or Secondary 3–4 in Quebec, in the baseline wave, as well as 41 students in Secondary 5 at baseline who repeated Secondary 5 at follow-up. From this linked sample, 2821 students were removed due to missing values on one or more variable(s). Students missing data to calculate BMI (due to missing weight, height, age, and/or sex) were retained in the sample and categorized as having a ‘not stated’ BMI, given the large amount of missingness on this variable and likelihood that it is not missing completely at random [22, 23]. The total complete case sample included 20,485 students from 112 schools. The front page of the questionnaire includes a set of questions to create a code to link student data across waves, while preserving anonymity. Additional details on the data linkage process can be found in print [24, 25].

Measures

Generalized anxiety symptoms (dependent variable)

The seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale [26] was used to assess symptoms of generalized anxiety and has demonstrated validity for use among clinical and nonclinical adolescent populations [26,27,28]. The scale asks “over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems?” for the following seven complaints: “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge”, “not being able to stop or control worrying”, “worrying too much about different things”, “trouble relaxing”, “being so restless that it is hard to sit still”, “becoming easily annoyed or irritable”, and “feeling afraid as if something awful might happen” with an internal consistency of 0.92 [26]. The response options were as follows: “not at all”, “several days”, “over half the days” and “nearly every day”, scored 0 to 3, respectively. The responses were summed for a scale that ranged from 0 to 21, with a score of 10 or greater indicating clinically relevant anxiety symptoms [26].

Depression symptoms (dependent variable)

To assess risk for, or symptoms of, unipolar depression, the student questionnaire includes the ten-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Revised (CESD-R-10) [29, 30]. Its use is found to be valid and reliable among general populations of youth [29, 31, 32]. The scale asks “on how many of the last 7 days did you feel the following ways?” for the following ten complaints: “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me”, “I had trouble keeping my mind of what I was doing”, “I felt depressed”, “I felt that everything I did was an effort”, “I felt hopeful about the future”, “I felt fearful”, “My sleep was restless”, “I was happy”, “I felt lonely”, and “I could not get ‘going’” with an internal consistency of 0.91 [30]. The response options were as follows: “not at all”, “several days”, “over half the days”, and “nearly every day” scoring 0 to 3, respectively (items “I felt hopeful about the future” and “I was happy” were reverse scored). The responses were summed for a scale that ranged between 0 and 30, with scores of 10 or above indicating significant depressive symptoms [29, 30].

Weight perception (independent variable)

Weight perception was assessed by asking youth “how do you describe your weight” and they had the following options to choose from: “very underweight”, “slightly underweight”, “about the right weight”, “slightly overweight” or “very overweight”. For this analysis, “very underweight” and “slightly underweight” and “slightly overweight” and “very overweight” were combined.

Social health (independent variables)

Social health consisted of measures from: peers, family, teachers, school belonging, and rewarding and supportive relationships. The question asks “How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements?” for “I can talk about my problems with my friends”, “I can talk about my problems with my family”, “I have a happy home life”, “My parents/guardians expect too much of me”, “I feel the teachers at my school treat me fairly”, “I feel I am part of my school”, “I feel safe in my school”, “My social relationships are supportive and rewarding”, and “People respect me”. The five response options (from strongly disagree to strongly agree), were collapsed into agree (“strongly agree” or “agree”) and disagree/neutral (“neither agree nor disagree", "disagree" or "strongly disagree").

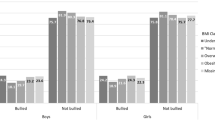

Bullying status was assessed by asking “In the last 30 days, how often have you been bullied by other students?” to identify victims of bullying and “In the last 30 days, how often have you taken part in bullying other students?” to identify perpetrators of bullying. If youth reported any bullying or perpetrating behaviour, they were considered victims of bullying or perpetrators of bullying, respectively. Those who participated in both were categorized as “bully-victims” and youth who did not report any of these behaviours were categorized as “none”.

Covariates

The variables weight status, race/ethnicity, and grade were used as control variables in our study. Weight status was determined from BMI using youth’s self-reported weight (in kilograms) and height (in meters). The World Health Organization’s (WHO) age- and sex-specific cut-off points (ages 13–18 years old) were used to classify weight status [33]. The measures used to determine BMI in COMPASS have been previously validated (ICC = 0.84) [34]. You who did not report weight or height information were categorized as ‘not stated’ in the analyses.

Youth reported their race/ethnicity when answering the question “How would you describe yourself? (Mark all that apply)” and they chose from “White”, “Black”, “Asian”, “Aboriginal (First Nation, Métis, Inuit)”, “Latin American/Hispanic”, and “Other”. For our analysis, we generated a dichotomous variable consisting of the racial-ethnic majority (White) and grouped the racial-ethnic minorities (non-White).

Youth reported their current Grade [9, 10, 11, 12]. In Quebec students, Secondary II, IV, and V were classified as Grade 9, 10, and 11, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Differences in baseline and follow-up sample characteristics between females and males were examined using chi-squared tests. As for the dependent variables, differences at baseline and follow-up between females and males were examined using t tests. Since there were significant differences between females and males on both outcomes and many predictor variables, analyses were stratified by gender.

The regression analysis consisted of linear mixed-effects models (with a random intercept term to account for school-level clustering) to examine the prospective association between weight perception (at Wave 6) and social health (at Wave 6) with anxiety and depression (at Wave 7 i.e., reflecting a 1-year follow-up) while controlling for weight status, ethnicity, and grade (at Wave 6).

Additional models were run which added interaction terms with weight perception for significant social health variables. To observe for differences in the predicted average GAD-7 and CESD-10-R scores by weight perception, we used the predicted least-squares means for Wave 7 after accounting for all the other variables in the model. Separately, we added social health at Wave 7 (reflecting a 1-year follow-up) to the models. These models had the same overall findings as the models without the social health at Wave 7 variables; thus, we presented the set of models without them following the law of parsimony. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 [35].

Results

Our sample consisted of 54% female and 46% male youth, who were primarily in grades 9 (39%), 10 (38%), and 11 (23%), given the lack of a grade 12 equivalent in Quebec schools. The vast majority reported a White ethnicity (75.9%). Sample descriptive statistics are displayed in Table 1.

Weight perception

Table 1 displays differences in weight perception, weight status, and other characteristics across female and male youth at baseline. Gender differences are apparent in weight perception. Table 1 shows that females tended to perceive their weight as about the right weight and overweight more than males (females: about the right weight = 63.2%, overweight = 26.1%; males: about the right weight = 56.5, overweight = 21.0%; p < 0.0001), while more males reported an underweight perception (males = 22.5%; females = 10.7%; p < 0.0001) at baseline.

Among those who did not report their weight/height (4782 youth out of 20,485), 29% reported a perception of overweight while 56.7% reported a perception of ‘about the right weight’ and 14.3% reported an underweight perception.

Social health

There were gender differences regarding perceived social support from friends and family. More males agreed that they can talk about their problems with their family (males = 62.8%, females = 55.9%, p < 0.0001 at baseline). Males also reported a happy home life more often than their female counterparts (males = 85.8%, females = 76.2%, p < 0.0001 at baseline). There were also gender differences in youth’s school belonging and rewarding and supportive relationships at baseline, with similar results reported at follow-up. More males reported feeling a part of their school (males = 79.2%, females = 74.4%, p < 0.0001 at baseline) than females. Males also reported more agreement that their social relationships are rewarding and supportive (males = 78.1%, females = 75.4%, p < 0.0001 at baseline). Female and male youth did not have differences in agreeing that parents expected too much of them (females = 30.5%, males = 30.0%, p = 0.4123) nor did they report differences in the fair treatment from their teachers (females = 85.5%, males = 85.7%, p = 0.645) at baseline with similar results reported at follow-up (Table 1).

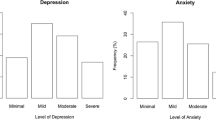

Anxiety and depression

Table 2 presents a summary of the anxiety and depression measures at baseline and at follow-up. There were significant gender differences as females reported much higher anxiety at baseline (females: \(\overline{x}\) = 7.8, σ = 5.7; males: \(\overline{x}\) = 4.6, σ = 4.7; p < 0.0001) and follow-up (females: \(\overline{x}\) = 8.4, σ = 5.7; males: \(\overline{x}\) = 5.1, σ = 5.0; p < 0.0001) relative to their male counterparts. Females also reported a higher depression mean score than their male counterparts at baseline (females: \(\overline{x}\) = 9.7, σ = 6.2; males: \(\overline{x}\) = 7.1, σ = 5.0; p < 0.0001) and follow-up (females: \(\overline{x}\) = 10.5, σ = 6.3; males: \(\overline{x}\) = 7.8, σ = 5.5; p < 0.0001).

Regression results: anxiety

Females

Table 3 shows results among females from the models that regressed the GAD-7 anxiety score on weight perception and social health factors while adjusting for covariates. A perception of overweight among females is associated with a 0.45-unit increase (95% CI = 0.23, 0.67) on the anxiety scale. Our predicted least-squares mean estimations predicted that females with overweight perception have a score of 9.32, just under the cut-off score of 10 that indicates clinically relevant anxiety symptoms [26].

Two social health factors were associated with a higher anxiety score: being a victim of bullying (β = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.35, 0.89) and a perception that parents expect too much of them (β = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.13, 0.53). Several of the social health factors were associated with lower anxiety: can talk about problems with family (β = − 0.26, 95% CI = − 0.45, − 0.06), feel a part of their school (β = − 0.36, 95% CI = − 0.58, − 0.14), feel safe at school (β = − 0.32, 95% CI = − 0.61, − 0.04) and a perception of that people respect them (β = − 0.47, 95% CI = − 0.68, − 0.26). The moderating impact of social health factors that were significant in this model were tested as interaction terms with weight perception in Model 4; however, none were found to be significant (results displayed in Supplementary Table 1).

Males

Table 4 shows results among males from the models that regressed the GAD-7 anxiety score on weight perception and social health factors while adjusting for covariates. A weight perception of underweight and overweight among males is associated with a 0.34-unit increase (95% CI = 0.12, 0.56) and a 0.42-unit increase (95% CI = 0.16, 0.67) respectively, on the anxiety scale. Our predicted least-squares mean estimations show the predicted average scores for males’ anxiety levels are lower than females’, at 6.13 for those with an overweight perception; therefore, males with an overweight perception are not reporting clinically relevant anxiety symptoms.

Being a victim of bullying was the only social health factor associated with higher anxiety (β = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.12, 0.73). The social health factors that were associated with lower anxiety were the same factors that were identified among females. The moderating influence of social health factors that were significant in this model were tested as interaction terms; only one interaction, between a perception of underweight and feeling safe at school, was significantly associated with a lower anxiety score (β = − 0.82, 95% CI = − 1.54, − 0.09) (results displayed in Supplementary Table 2).

Regression results: Depression

Females

Table 5 shows results among females from the models that regressed the depression score on weight perception and social health factors while adjusting for covariates. A perception of overweight among females is associated with a 0.51 unit increase (95% CI = 0.27, 0.75) on the depression scale. Our predicted least-squares mean estimations found that all females have an anxiety score over 10, where scores of 10 or above indicate clinically significant depressive symptoms [29, 30]. The highest predicted score was 12 among females with an overweight perception; the second highest score of 11.68 was among females with an underweight perception. Our results suggest that female youth have significant depressive symptoms, particularly those with an overweight perception.

Two social health factors were associated with higher depression: being a victim of bullying (β = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.37, 0.95) and a perception of parents expecting too much of them (β = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.34, 0.78). Many of the social health factors were associated with lower depression, mainly those that were also associated with lower anxiety, with the addition of youth reporting a happy home life (β = − 0.44, 95% CI = − 0.69, − 0.19). Other social health factors were: can talk about problems with family (β = − 0.51, 95% CI = − 0.73, − 0.29), feel a part of their school (β = − 0.58, 95% CI = − 0.82, − 0.34), feel safe at school (β = − 0.57, 95% CI = − 0.89, − 0.26) and perceive people to respect them (β = − 0.48, 95% CI = − 0.71, − 0.24). The moderating influence of social health factors that were significant were tested as interaction terms with weight perception; however, none were found to be significant (results displayed in Supplementary Table 3).

Males

Table 6 shows results among males from the models that regressed the depression score on weight perception and social health while adjusting for covariates. A weight perception of overweight among males is associated with a 0.33-unit increase (95% CI = 0.06, 0.60) on the depression scale. Among male youth, an overweight perception is associated with 1.3 unit increases in the CESD-R-10 depression scale across their secondary school years. Our predicted least-squares mean estimations show that males with an overweight perception have a CESD-R-10 score of 8.93, slightly below the cut-off that would classify them with significant depressive symptoms.

Two social health factors were associated with higher depression and they had to do with bullying status: being a victim of bullying (β = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.46, 1.11) and being a victim and perpetrator of bullying (β = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.26, 0.95), relative to not being a bullying victim or perpetrator. Many of the social health factors were associated with lower depression, and they were the same as those reported among females. The moderating influence of social health factors that were significant were tested as interaction terms; only one interaction, between a weight perception of overweight and rewarding social relationships, was significantly associated with a higher depression score (β = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.13, 1.38) (results displayed in Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

We found that an overweight perception is associated with higher anxiety and depression scores after 1 year, among youth in Canada while, an underweight perception was associated with higher scores 1 year later among males only. While an overweight perception is associated with increases in the depression scale among both genders, only females with an overweight perception were found to have significant depressive symptoms during secondary school, possibly because females have a higher mean depression score.

A variety of social health factors were associated with lower anxiety and depression scores among female and male youth. Even though social health contributed to less anxiety and depression, it did not play a moderating role in the prospective relationship between weight perception and anxiety and depression among females. As for males, feeling safe at school had a protective effect on anxiety scores among males with underweight perceptions 1 year later, relative to males with about right perceptions and who did not feel safe while rewarding social relationships among males with overweight perceptions were associated with higher depression scores relative to their peers.

Among Canadian youth, perception of overweight is detrimental to the mental health of both females and males. A systematic review and meta-analysis also found that perceived overweight is associated with poor mental health (depression and suicidality) among females and males and across age-groups (children and adults); however, they did not investigate anxiety [1]. Studies among youth in the U.S.A. and China found such associations among only females [12, 13]. A previous cross-sectional analysis of the COMPASS study found both overweight and underweight perceptions to be associated with greater depression and anxiety symptoms, and lower flourishing, in both females and males [5]. There are other gender-based differences such as in perceptions of physical attractiveness. Societal ideals are more accepting of females having low weight status (or a small body size) versus the societal ideals of males which are more favorable of a larger, muscular body size [36]. This may explain our finding that a perception of underweight was associated with a higher anxiety score 1 year later among males only. In contrast, a study in Australia found that an underweight perception was associated with lower quality of life scores among females only [37]. Mixed results by gender may reflect differences by geographic locations, potentially related to weight norms. Further research is needed to build upon these mixed findings and clarify to what extent populations of youth have different associations between weight perception and anxiety and depression.

Social health was associated with lower depression and anxiety scores 1 year later. The Main-Effects Model emphasizes the importance of social health [38, 39]. It suggests that social support is positively associated with positive health effects and negatively associated with negative health effects [38]. However, research that followed this seminal article found that not all social health factors are associated with positive health effects; rather, these effects may differ depending on the type of support being studied [39].

In our findings, the social health factors that were associated with lower anxiety and depression for both females and males spanned: perceiving they can share their problems with their family, feeling a sense of belonging and safety at their school, as well as a general perception that people respect them. Our results show that these four social health factors are individually associated with decreases in anxiety and depression (via the beta coefficients) among female and male youth. It is worthy to note that evaluating for the cumulative association of the support factors is very likely to have a synergistic effect on mental health. This also indicates that if the betas are added across youth with low levels of support across the board, the betas become meaningful and youth who are report not feeling support have a cumulative higher risk of anxiety and depression. This is an area for future research to investigate.

Our findings support a comprehensive social support system (i.e., family, friends, school, general social networks) to enhance mental health among female and male youth. This finding aligns with viewing social health from an ecological perspective which considers multiple influences on development from different environments [40]. In this model, both environments and relationships are considered when assessing the association of social health with positive development [40].

We find that social health does not play a role in the association between weight perception and depression and anxiety among females, while only two interactions were significant among males: feeling safe at school had a protective association among males with perception of underweight and the effect of rewarding social relationships had a negative association among males with perception of overweight. One possible explanation is that supportive social influences positively influence youth’s mental health; but, they do not negate the impact of internalized weight bias towards their body image [41]. In male youth, a systematic review found that friends and peers can contribute to body dissatisfaction through teasing, modeling, comparing appearances and social conflict and these can be passive-aggressive communications [42]; thus, the quality of male youth’s rewarding social relationships should be cautiously interpreted.

Strengths of our study include the use of prospective-linked data from a large sample of youth in Canada, validated depression and anxiety scales, and inclusion of a variety of social health factors in gender-specific analyses. As for limitations, BMI was based on self-reported weight and height; although the weight status measure in COMPASS is valid and reliable for use among youth populations [34]. We used complete cases which is a potential bias for weight status and anxiety and depression since these individuals may be at a higher risk of anxiety or depression [19]. We did not control for eating disorders which may moderate the relationship between weight perception and mental ill-health [6, 9]. Although gender-specific, gender was only assessed as a binary construct due to survey measures.

Conclusion

In a prospective analysis among a large sample of Canadian adolescents, an overweight perception was associated with higher anxiety and depression scores 1-year later, while supportive social influences were associated with lower scores among both females and males. An underweight perception was also associated with higher depression and anxiety scores among males only. Social influences did not moderate the association between an overweight perception and mental health. This study suggests that social support factors are not sufficient to protect against for the adverse associations between overweight perceptions for all youth, and underweight perceptions for males, on depression and anxiety. Interventions preventing weight perceptions differing from about the right weight and targeting weight bias may prove effective for prevention of internalizing disorders among adolescents.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due restrictions on sharing the data but are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Code availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due restrictions on sharing the code but are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Haynes A, Kersbergen I, Sutin A, Daly M, Robinson E (2019) Does perceived overweight increase risk of depressive symptoms and suicidality beyond objective weight status? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 73:101753

Swahn MH, Reynolds MR, Tice M, Miranda-Pierangeli MC, Jones CR, Jones IR (2009) Perceived overweight, BMI, and risk for suicide attempts: findings from the 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J Adolesc Heal 45:292–295

Lo WS, Ho SY, Mak KK, Wong YM, Lai YK, Lam TH (2009) Prospective effects of weight perception and weight comments on psychological health among Chinese adolescents. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. 98:1959–1964

Robinson E, Haynes A, Sutin A, Daly M (2020) Self-perception of overweight and obesity: a review of mental and physical health outcomes. Obes Sci Pract 6(5):552–561

Patte KA, Livermore M, Qian W, Leatherdale ST (2021) Do weight perception and bullying victimization account for links between weight status and mental health among adolescents? BMC Pub Health 21:1062

Kim DS, Cho Y, Cho SIL, Lim IS (2009) Body weight perception, unhealthy weight control behaviors, and suicidal ideation among Korean adolescents. J Sch Health 79:585–592

Mamun AA, Cramb S, McDermott BM, O’Callaghan M, Najman JM, Williams GM (2007) Adolescents’ perceived weight associated with depression in young adulthood: a longitudinal study. Obesity 15(12):3097–3105

Zarrella I, Russolillo LA, Caviglia G, Perrella R (2017) Continuity and discontinuity between psychopathology of childhood and adulthood: a review on retrospective and prospective studies. Res Psychother Psychopathol Process Outcome 20(2):248

Cornette R (2008) The emotional impact of obesity on children. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs 5:136–141

Stradmeijer M, Bosch J, Koops W, Seidell J (2000) Family functioning and psychosocial adjustment in overweight youngsters. Int J Eat Disord 27:110–114

Perrin EM, Boone-Heinonen J, Field AE, Coyne-Beasley T, Gordon-Larsen P (2010) Perception of overweight and self-esteem during adolescence. Int J Eat Disord 43(5):447–454

Seo DC, Lee CG (2013) The effect of perceived body weight on suicidal ideation among a representative sample of US adolescents. J Behav Med 36:498–507

Vogt Yuan AS (2007) Gender differences in the relationship of puberty with adolescents’ depressive symptoms: do body perceptions matter? Sex Roles 57:69–80

Emmer C, Bosnjak M, Mata J (2020) The association between weight stigma and mental health: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 21(1):e12935

Bandura A (1989) Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol 44(9):1175–1184

Rawana JS (2013) The relative importance of body change strategies, weight perception, perceived social support, and self-esteem on adolescent depressive symptoms: longitudinal findings from a national sample. J Psychosom Res 75:49–54

Christoph MJ, Jarrett ES, Gower AL, Borowsky IW (2018) Weight status and weight perception in relation to mental distress and psychosocial protective factors among adolescents. Acad Pediatr 18:51–58

Xie B, Liu C, Chou CP, Xia J, Spruijt-Metz D, Gong J et al (2003) Weight perception and psychological factors in Chinese adolescents. J Adolesc Heal 33:202–210

Chartier M, Van der Stoep A, McCauley E, Herting JR, Tracy M, Lymp J (2008) Passive versus active parental permission: Implications for the ability of school-based depression screening to reach youth at risk. J Sch Health 78:157–164

White VM, Hill DJ, Effendi Y (2004) How does active parental consent influence the findings of drug-use surveys in schools? Eval Rev 28:246–260

Leatherdale ST, Brown KS, Carson V, Childs RA, Dubin JA, Elliott SJ et al (2014) The COMPASS study: a longitudinal hierarchical research platform for evaluating natural experiments related to changes in school-level programs, policies and built environment resources. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 14(1):331. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24712314

Aceves-Martins M, Whitehead R, Inchley J, Giralt M, Currie C, Solà R (2018) Self-reported weight and predictors of missing responses in youth. Nutrition 53:54–58

Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Faulkner GE, Leatherdale ST (2010) Learning from non-reported data: Interpreting missing body mass index values in young children. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci [Internet]. 14(4):241–51. https://shapeamerica.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2010.520243

Battista K, Qian W, Bredin C, ST L (2019) Student data linkage over multiple years [Internet]. Waterloo, Ontario. https://uwaterloo.ca/compass-system/student-data-linkage-over-multiple-years. cited 23 May 2020

Qian W, Battista K, Bredin C, Brown KS, Leatherdale ST (2015) Assessing longitudinal data linkage results in the COMPASS study [Internet]. Vol. 3. University of Waterloo. Available from: https://uwaterloo.ca/compass-system/sites/ca.compass-system/files/uploads/files/compass_report_-_assessing_longitudinal_data_linkage_results_-_volume_3_issue_4.pdf

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10):1092–1097

Mossman SA, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK, Varney ST, Fleck DE, Barzman DH et al (2017) The generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: Signal detection and validation. Ann Clin Psychiatry 29(4):227–234A

Tiirikainen K, Haravuori H, Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M (2019) Psychometric properties of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) in a large representative sample of Finnish adolescents. Psychiatry Res 272:30–35

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1:385–401

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL (1994) Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med 10:77–84

Bradley KL, Bagnell AL, Brannen CL (2010) Factorial validity of the center for epidemiological studies depression 10 in adolescents. Issues Ment Health Nurs 31:408–412

Haroz EE, Ybarra ML, Eaton WW (2014) Psychometric evaluation of a self-report scale to measure adolescent depression: the CESDR-10 in two national adolescent samples in the United States. J Affect Disord 158:154–160

World Health Organization (2007) Children growth reference [Internet]. http://www.who.int/growthref/who2007_bmi_for_age/en/index.html

Leatherdale ST, Laxer RE (2013) Reliability and validity of the weight status and dietary intake measures in the COMPASS questionnaire: are the self-reported measures of body mass index (BMI) and Canada’s food guide servings robust? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 10:42

SAS Institute Inc (2013) SAS 9.4. SAS Institute Inc, Cary

Ata RN, Ludden AB, Lally MM (2007) The effects of gender and family, friend, and media influences on eating behaviors and body image during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 36:1024–1037

Hayward J, Millar L, Petersen S, Swinburn B, Lewis AJ (2014) When ignorance is bliss: weight perception, body mass index and quality of life in adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 38:1328–1334

Cohen S, Wills TA (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 98:310–357

Rueger SY, Malecki CK, Pyun Y, Aycock C, Coyle S (2016) A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychol Bull 142:1017–1067

Bronfenbrenner U (2005) Making human beings human: bioecological perspectives on human development. Sage Publications Ltd.

Voelker D, Reel J, Greenleaf C (2015) Weight status and body image perceptions in adolescents: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther 6:149–158

Webb HJ, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (2014) The role of friends and peers in adolescent body dissatisfaction: a review and critique of 15 years of research. J Res Adolesc 24:564–590

Funding

The COMPASS study has been supported by a bridge grant from the CIHR Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes (INMD) through the “Obesity—Interventions to Prevent or Treat” priority funding awards (OOP-110788; awarded to SL), an operating grant from the CIHR Institute of Population and Public Health (IPPH) (MOP-114875; awarded to SL), a CIHR project grant (PJT-148562; awarded to SL), a CIHR bridge grant (PJT-149092; awarded to KP/SL), a CIHR project grant (PJT-159693; awarded to KP), and by a research funding arrangement with Health Canada (#1617-HQ-000012; contract awarded to SL). The COMPASS-Quebec project additionally benefits from funding from the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux of the province of Québec, and the Direction régionale de santé publique du CIUSSS de la Capitale-Nationale.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

This study used a convenience sample of secondary schools and boards based on permitted use of active-information passive-consent protocols among youth.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hammami, N., Patte, K., Battista, K. et al. Examining the role that weight perception and social influences have on mental health among youth in the COMPASS study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57, 1671–1684 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02219-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02219-9