Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to investigate the associations between quality of life and both perceived and objective availability of local green and blue spaces in people with dementia, including potential variation across rural/urban settings and those with/without opportunities to go outdoors.

Methods

This study was based on 1540 community-dwelling people with dementia in the Improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life (IDEAL) programme. Quality of life was measured by the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) scale. A list of 12 types of green and blue spaces was used to measure perceived availability while objective availability was estimated using geographic information system data. Regression modelling was employed to investigate the associations of quality of life with perceived and objective availability of green and blue spaces, adjusting for individual factors and deprivation level. Interaction terms with rural/urban areas or opportunities to go outdoors were fitted to test whether the associations differed across these subgroups.

Results

Higher QoL-AD scores were associated with higher perceived availability of local green and blue spaces (0.82; 95% CI 0.06, 1.58) but not objective availability. The positive association between perceived availability and quality of life was stronger for urban (1.50; 95% CI 0.52, 2.48) than rural residents but did not differ between participants with and without opportunities to go outdoors.

Conclusions

Only perceived availability was related to quality of life in people with dementia. Future research may investigate how people with dementia utilise green and blue spaces and improve dementia-friendliness of these spaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

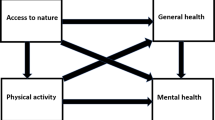

Interaction with the natural environment, such as visiting gardens, parks, woodlands and rivers and coastal areas, termed green and blue spaces, has been associated with better health and wellbeing in the general population [1, 2] as well as among people with dementia [3,4,5,6]. Previous research has suggested that access to nature might have beneficial influences on physical activity, psychological health and wellbeing in people with dementia and contribute to reduction in dementia-related symptoms [6,7,8,9,10]. However, most existing studies are based on relatively small numbers of people with dementia living in residential care settings and have generally used qualitative methods [3]. There is a lack of empirical evidence from community-dwelling people with dementia and how their interactions with the local natural environment may support people to live well with the condition.

Perceptions of the natural environment are likely to be linked to experiences of environmental interactions in the wider context of social networks, mobility and sociocultural systems [11]. Individual factors, such as sociodemographic characteristics and health status, as well as collective factors, such as values, norms and social networks, may modify behaviour and the use of the environment in certain subgroups [11, 12]. For example, people with low socioeconomic status generally have poor access to green space and the quality of green space is reported to be worse in more deprived areas [13, 14]. People with dementia who experience changes in cognitive function and health status might also have different perceptions of the availability of green and blue spaces, reflecting their experiences of access to and engagement with these environmental features [3]. Thus, perceived availability of green and blue spaces should not be considered as a proxy for objective availability of green and blue spaces, which is generally measured using national statistics, maps or geographic information system (GIS) data [15]. While the objective measures indicate actual areas of green and blue spaces, the perceived measures may reflect individual subjective experience of interacting with these spaces. To investigate the role of green and blue spaces in supporting people to live well with dementia, it is important to consider variation between perceived and objective measures and investigate the potential impact of these on quality of life, a key outcome measure in dementia care research focusing on individual perception of wellbeing, happiness, goodness and satisfaction with various aspects of life [16, 17].

Based on a large cohort study of people with dementia in Great Britain, the aim of this study was to examine perceived and objective availability of local green and blue spaces and their associations with quality of life. The analysis also investigated whether the associations of quality of life with perceived and objective availability of green and blue spaces varied across those with different individual (with and without opportunities to go outdoors) and area-level (urban and rural settings) factors.

Methods

Study population

The Improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life (IDEAL) programme is a longitudinal cohort study of 1540 community-dwelling people with dementia and 1278 carers in Great Britain [18, 19]. More detailed information on study design and the profile of the IDEAL study population has been reported previously [18, 20]. In brief, IDEAL aims to identify social, psychological and economic factors that support people to live well with dementia. Recruitment was carried out through a network of 29 National Health Service sites across England, Scotland and Wales between July 2014 and August 2016. All participants were required to have a clinical diagnosis of dementia and a Mini-Mental State Examination score ≥ 15 on entry to the study. People with dementia who were not able to provide informed consent were excluded from recruitment. For each person with dementia, a carer who provided practical or emotional unpaid support was also recruited where possible. For those who agreed to take part, a trained researcher visited them at home and implemented standardised questionnaires at baseline and two follow-up interviews 12 and 24 months later. Among 3105 people with dementia who were approached by the IDEAL researchers, 378 were ineligible, 1106 declined and 81 withdrew subsequently. The response rate was 56% among eligible people with dementia.

The study was approved by the Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 (reference: 13/WA/0405) and the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, Bangor University (reference: 2014-11684). The study is registered with the UK Clinical Research Network, registration number 16593. This analysis focused on the baseline data of 1540 people with dementia.

Quality of life

People with dementia rated their quality of life using the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease scale (QoL-AD), a dementia-specific measure of quality of life with good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.88) and test–retest reliability (intra-class correlation coefficient = 0.76) [21]. In the IDEAL study, the Cronbach’s α of QoL-AD was estimated to be 0.86 [22]. The scale includes 13 items on mood, memory, functional abilities and interpersonal relationships and a 4-level Likert response scale for each item (poor, fair, good and excellent). A higher score (range 13–52) indicates better quality of life.

Perceived availability of green and blue spaces

To measure the availability of local green and blue spaces, the IDEAL questionnaire provided a list of different possible types of green and blue space and people with dementia were asked which of the following 12 types of green and blue spaces were within a 10-minute walk of their dwelling (yes/no): countryside; woodlands; parks and gardens; country parks; green corridors; outdoor sports facilities; amenity green space; play areas; allotments, community gardens and urban farms; cemeteries and churchyards; river, lake or canal; and sea [23]. The option of ‘none of the above’ was also provided. The total number of local green and blue spaces was calculated based on the sum of these 12 items and was divided into quartiles (0–4, 5–6, 7–8, 9–12). A higher number indicates perceived availability of more of these spaces in the local area.

Objective availability of green and blue spaces

GIS data were used to measure objective availability of green and blue spaces in local areas. The Ordnance Survey (OS) Open Greenspace data [24] provide the location and extent of green spaces that are likely to be accessible to the public across Great Britain, including allotments or community growing spaces, bowling greens, cemeteries, religious grounds, golf courses, other sports facilities, play spaces, playing fields, public parks or gardens, and tennis courts. The OS Open Rivers data [25] provide information on the watercourse network including freshwater rivers, tidal estuaries and canals in Great Britain. Given the time points of the IDEAL baseline interview, the earliest available versions were obtained for the greenspace (version July 2017) and river data (version October 2016) via Digimap (digimap.edina.ac.uk).

Postcode information relating to the IDEAL participants’ places of residence was converted into the National Grid reference, a UK-based coordinate system [26]. For each participant, a 400-metre (m) buffer based on individual residence was generated as a proxy for a 10-min walking area for people with dementia [27]. The areas (square metres) of green spaces within the buffers were calculated and divided into quartiles. To match with the perceived measure, different types of green spaces were categorised into five groups: allotment or community growing spaces; cemeteries or religious grounds; public parks or gardens; sports spaces; and play spaces. For blue spaces, the OS Open Rivers data were used to identify any rivers within the 400-m buffers and the UK coastline was used to identify seas within the buffers. The measure for blue spaces was categorised into three groups: none; river or sea; and both. All GIS data were managed and analysed using ArcGIS 10.3.1.

Covariates

The IDEAL interviews collected information on age, sex, education and social class for people with dementia. The highest educational qualification was used to divide participants into three groups: low (no qualification), middle (school-leaving qualification at age 16) and high (higher school-leaving qualification at age 18 or above). Social class was defined using the main occupation in working life and the current standard occupational classification for the UK (SOC 2010) system. The measure was categorised into three social class groups: high (professional or managerial occupations); middle (skilled occupations); and low (partly skilled, unskilled occupations or armed forces). In addition to sociodemographic factors, health status and walking speed might affect perceived availability of local green and blue spaces. Self-rated health over the past 4 weeks was used to measure overall health status and categorised into three groups: very poor/poor; fair; good/very good/excellent [28]. Self-reported walking speed of people with dementia was divided into three levels: slow pace; steady average pace; brisk or fast pace [29]. The opportunity to go outdoors in the last 2 weeks was measured using a single question: “Have you had an opportunity to be outside, go for walks, enjoy nature?” with a binary answer of yes/no [30].

Two area-level measures, area deprivation and rural/urban areas, were linked to the IDEAL participants through postcode information. More detailed information is provided in a previous study [31]. In brief, the deprivation index, which summarised characteristics related to poverty and socioeconomic disadvantage including income, employment, education and training, health and disability, barriers to housing and services, the living environment and crime, were divided into quintiles among all area units for England, Scotland and Wales. The first quintile (Q1) represents 20% of the most deprived areas in the country. Rural/urban areas were defined based on 2011 Census Rural Urban Classification (England and Wales) and Scottish Government Urban Rural Classification 2013–2014 (Scotland).

Statistical analyses

To investigate whether the perceived availability of local green and blue spaces corresponded to the objective measures, the percentages of agreement (both available or not available) were reported for specific types of green and blue spaces, including parks, sport spaces, play areas, allotments and community gardens, cemeteries and religious grounds, rivers and seas. Since a 10-min walking distance may differ due to individual walking speed, the percentages of agreement were also stratified by self-reported walking speed.

Regression modelling was carried out to investigate the associations of quality of life with perceived and objective availability of green and blue spaces in people with dementia. The quartiles of perceived and objective availability measures were fitted in the modelling and adjusted for sociodemographic factors (age, gender, education and social class), self-rated health, walking speed and area deprivation. A full model was fitted to include both perceived and objective measures in order to test whether one of them had stronger associations with quality of life. Multicollinearity was checked using variance inflation factor (VIF) and remained low in the full model (VIF = 1.60). Since people who had opportunities to go outdoors might have different interactions with green and blue spaces from those who did not have these opportunities, the analysis included interaction terms between opportunities to go outdoors (yes/no) and perceived or objective measures for green and blue spaces. Green and blue spaces in urban areas may ameliorate noise, heavy traffic and pollution and therefore could be particularly important to urban residents. To investigate whether the associations of quality of life with green and blue spaces differed across urban and rural settings, interaction terms between rural/urban areas and perceived or objective measures for green and blue spaces were fitted into the modelling. Robust standard errors were estimated for all models.

To address missing data, multiple imputation was conducted using all variables included in the modelling. Estimates from 20 imputed datasets were combined using Rubin’s rules [32]. The imputed results of regression modelling are reported in this study. Test for trend was used to examine whether higher availability of local green and blue spaces was associated with higher quality of life. This study was based on the IDEAL baseline data version 4.5. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 15.1.

Results

Among the 1540 participants, the median age was 77 years with an interquartile range between 71 and 83. The percentage of men was 56.2% (Table 1). Most participants had secondary education or above (54.1%), professional or managerial occupations (44.7%) and lived in the least deprived areas (30.5%). Nearly 63% reported good, very good or excellent health. There were 46.1% people with dementia reporting average walking speed and 16.5% did not have opportunities to be outside and enjoy nature. Just over two-thirds of participants lived in urban settings.

Table 2 shows percentages of agreement between perceived and objective availability of green and blue spaces. Apart from sea (90.4%), the agreement was low in all types of green and blue spaces with the percentages ranging between 44.7 and 64.4%. The percentages of agreement remained similar when stratified by walking speed.

The mean QoL-AD score was 36.8 with a standard deviation (SD) of 5.9 among the 1396 participants without missing items. Table 3 reports the associations between quality of life and both perceived and objective availability of local green and blue spaces. Higher QoL-AD scorers were found for those reporting a higher availability of perceived green and blue spaces (1.31; 95% CI 0.46, 2.16) but not for those where objective measures of green and blue spaces indicated higher availability. After adjusting for all covariates, the association between quality of life and the perceived availability of green and blue spaces was attenuated (0.82; 95% CI 0.06, 1.58) but the test for trend remained statistically significant. The effect sizes were similar when including both perceived and objective measures for green and blue spaces in one model.

The associations of quality of life with perceived and objective availability of green and blue spaces did not differ across those with and without opportunities to be outside and enjoy nature (Fig. 1). Although people with dementia who did not go outdoors had lower quality of life scores, the interaction terms did not achieve statistical significance for perceived (p = 0.24) or objective green (p = 0.34) and blue spaces (p = 0.36). Urban and rural differences were only found in perceived availability of green and blue spaces (p = 0.03) (Fig. 2). In urban areas, a higher availability of perceived green and blue spaces was associated with higher quality of life (1.50; 95% CI 0.52, 2.48) but the association was less clear in rural areas.

Discussion

Main findings

Using a large cohort study of people with dementia in Great Britain, this study investigated the associations of quality of life with perceived and objective availability of local green and blue spaces. The agreement between perceived and objective measures for availability of green and blue spaces was generally low. Quality of life in people with dementia was associated with perceived availability of local green and blue spaces but not with objective measures of availability after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, self-rated health, walking speed and area deprivation. High availability of perceived green and blue spaces was particularly important for those living in urban settings.

Strengths and limitations

This study included a large and geographically spread sample of community-dwelling people with dementia in Great Britain. The GIS data which provide complete information on green and blue spaces across the three countries were integrated with the IDEAL cohort data. In addition to green spaces, the measure also included blue spaces, a different aspect of the natural environment and a novel research focus [33]. Moving beyond previous qualitative research, this analysis used quantitative approaches to compare the potential benefits of both perceived and objective availability of local green and blue spaces for quality of life in people with dementia taking into account individual and area level factors.

Due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, the results cannot indicate causal relationships. People with dementia might have changed their place of residence due to their health conditions and care needs, and hence might have been unfamiliar with new neighbourhood environments. However, 81% of participants had lived in their current place of residence for over five years. The GIS data for the objective availability of green and blue spaces were produced in 2016/2017, which was slightly later than the majority of baseline interviews. Yet areas of green and blue space should have been stable over this short period of time. The study population only included people with mild-to-moderate dementia and therefore the results cannot be generalised to those with severe dementia, who are likely to be homebound and have poor health and/or mobility. This study did not investigate how people with dementia used local green and blue spaces in their daily life. People with dementia might travel to certain green and blue spaces which are outside their local areas. In particular, the objective measures for local green and blue spaces were generated based on the 400-m buffers and this did not take into account individual mobility and activity space. However, the disagreement between perceived and objective measures of availability of green and blue spaces was not explained by walking speed. Participants who reported greater availability were likely to have more frequent interactions with the natural environment in their local areas and therefore the perceived measure might be influenced by level of usage of local green and blue spaces.

Interpretation of findings

Only perceived availability of local green and blue spaces was associated with quality of life in people with dementia. Low agreement between the perceived and objective availability measures confirmed that these two measures captured different aspects of local green and blue spaces and their relevance for people with dementia. While this study focused on people with mild-to-moderate dementia, the results correspond to the large body of previous quantitative research on healthy adults and older people, which has reported inconsistency between perceived and objective environmental measures and different relationships with physical activity and walking [34,35,36], mental health [37] and health-related quality of life [38]. This demonstrates that although people with dementia may have memory problems and difficulties with orientation, variation between perceived and objective environmental measures is likely to be observed in both those with and without dementia. On the other hand, evidence from qualitative research generally highlights positive experiences from engagement with nature in older people, including people with dementia [3]. Perceived availability was based on participants’ recollection, and participants might mainly report those green and blue spaces that are relevant to their daily lives. Compared to the objective availability measures, these perceived green and blue spaces might be more ‘meaningful’ due to people with dementia being able to access, use or enjoy these spaces. The different relationships with perceived and objective availability measures might reflect variation in participants’ interactions with nature or differential availability or quality of green and blue spaces which were easily accessible for people with dementia [39].

Perceived availability of local green and blue spaces was particularly important for people with dementia living in urban settings. Environmental stressors in urban areas such as noise, traffic and pollution can lead to distress and sensory overload [40, 41]. People with dementia who reported a higher number of local green and blue spaces might have more frequent interactions with these spaces in urban areas and experience stress reduction and psychological restoration in nature [2, 6]. Opportunities to go outdoors did not modify the associations of quality of life with perceived and objective availability of green and blue spaces. Although people who were homebound might not be able to directly interact with local green and blue spaces, they might still enjoy aesthetic views of nature from widows or balconies and receive some benefits of exposure to greenness [42].

Implications and future research directions

To enhance the positive influence of green and blue spaces on quality of life, it is important to explore how people with dementia interact with local green and blue spaces and examine their subjective experience of this. Qualitative research has identified several barriers to accessing green spaces [27, 43]. This includes individual factors such as lack of motivation and physical fitness and environmental issues such as safety concerns, accessibility, quality of green spaces and lack of dementia-friendly awareness [27, 39, 43]. Future research may investigate these issues in longitudinal studies, identifying potential changes with the progression of dementia and specific barriers and needs in those with advanced dementia. Recent studies have also used wearable devices to provide accelerometer and Global Position System (GPS) data [11]. This approach may provide empirical data on how people with dementia utilise green and blue spaces and inform possible interventions relating to specific individual and environmental factors.

Availability of data and material

IDEAL data were deposited with the UK data archive in April 2020 and will be available to access from April 2023. Details of how the data can be accessed after that date can be found here: https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/854293/.

References

Pearce J, Shortt N, Rind E, Mitchell R (2016) Life course, green space and health: incorporating place into life course epidemiology. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13(3):331

Hartig T, Mitchell R, De Vries S, Frumkin H (2014) Nature and health. Annu Rev Public Health 35:207–228

Clark P, Mapes N, Burt J, Preston S (2013) Greening dementia—a literature review of the benefits and barriers facing individuals living with dementia in accessing the natural environment and local greenspace. Natural England Commissioned Reports, Number 137. 2013. http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/6578292471627776. Accessed 26 Mar 2020

Whear R, Coon JT, Bethel A, Abbott R, Stein K, Garside R (2014) What is the impact of using outdoor spaces such as gardens on the physical and mental well-being of those with dementia? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15:697–705

Keady J, Campbell S, Barnes H, Ward R, Xia L, Caroline S, Simon B, Ruth E (2012) Neighbourhoods and dementia in the health and social care context: a realist review of the literature and implications for UK policy development. Rev Clin Gerontol 22:150–163

Orr N, Wagstaffe A, Briscoe S, Garside R (2016) How do older people describe their sensory experiences of the natural world? A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. BMC Geriatr 16:116

Mapes N (2011) Research project: living with dementia and connecting with nature—looking back and stepping forwards. Dementia Adventure CIC. https://dementiaadventure.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/green-exercise-and-dementia-neil-mapes-february-2011.pdf. Accessed 26 Mar 2020

Connell B, Sanford J, Lewis D (2007) Therapeutic effects of an outdoor activity program on nursing home residents with dementia. J Hous Elder 21(3/4):195–209

Chalfont G (2006) Connection to nature at the building edge: towards a therapeutic architecture for dementia care environments. University of Sheffield, Sheffield. http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/1241/2/Chalfont%2C_Garuth_Eliot.pdf. Accessed 26 Mar 2020

Brooker DJ, Woolley RJ, Lee D (2007) Enriching opportunities for people living with dementia in nursing homes: an evaluation of a multi-level activity-based model of care. Aging Ment Health 11(4):361–370

Kestens Y, Chaix B, Gerber P, Desprès M, Gauvin L, Klein O et al (2016) Understanding the role of contrasting urban contexts in healthy aging: an international cohort study using wearable sensor devices (the CURHA study protocol). BMC Geriatr 16:96

Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S (2002) Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med 55:125–139

Jennings V, Baptiste AK, Osborne Jelks N, Skeete R (2017) Urban green space and the pursuit of health equity in parts of the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(11):1432

Hoffimann E, Barros H, Ribeiro AI (2017) Socioeconomic inequalities in green space quality and accessibility—evidence from a southern European City. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(8):916

Orstad SL, McDonough MH, Stapleton S, Altincekic C, Troped PJ (2017) A systematic review of agreement between perceived and objective neighborhood environment measures and associations with physical activity outcomes. Environ Behav 49:904–932

Ready RE, Ott BR (2003) Quality of Life measures for dementia. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:11

Hoe J, Orrell M, Livingston G (2010) Quality of life measures in old age. In: Abou Saleh M, Anand K, Katona C (eds) Principles and practice of geriatric psychiatry, 3rd edn. Wiley Blackwell, Chichester, pp 183–192

Clare L, Nelis SM, Quinn C, Martyr A, Henderson C, Hindle JV et al (2014) Improving the experience of dementia and enhancing active life - living well with dementia: study protocol for the IDEAL study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 12:164

Silarova B, Nelis SM, Ashworth RM, Ballard C, Bieńkiewicz M, Henderson C et al (2018) Protocol for the IDEAL-2 longitudinal study: following the experiences of people with dementia and their primary carers to understand what contributes to living well with dementia and enhances active life. BMC Public Health 18(1):1214

Clare L, Wu YT, Jones IR, Victor CR, Nelis SM, Martyr A et al (2019) A comprehensive model of factors associated with subjective perceptions of “living well” with dementia: findings from the IDEAL study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 33(1):36–41

Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L (1999) Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: patient and caregiver reports. J Ment Health Aging 5(1):21–32

Opdebeeck C, Katsaris MA, Martyr A, Lamont RA, Pickett JA, Rippon I et al (2020) What are the benefits of pet ownership and care among people with mild-to-moderate dementia? findings from the IDEAL programme. J Appl Gerontol 7:733464820962619

Welsh Government (2013) National Survey for Wales, 2012–2013. Welsh Government, Cardiff. https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/WGNS01/WGNS01.pdf. Accessed 20 Apr 2018

The Ordnance Survey Open Greenspace. https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/business-government/products/open-map-greenspace. Accessed 26 Mar 2020

The Ordnance Survey Open Rivers. https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/business-government/products/open-map-rivers. Accessed 26 Mar 2020

The Ordnance Survey Getoutside. A beginner’s guide to national grid reference. https://getoutside.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/guides/beginners-guide-to-grid-references/. Accessed 26 Mar 2020

Burton E, Mitchell L (2006) Inclusive urban design: streets for life. Architectural Press, Oxford

Bowling A (2005) Just one question: if one question works, why ask several? J Epidemiol Community Health 59(5):342–345

National Health Service (2009) The General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ): a screening tool to assess adult physical activity levels, within primary care. Department of Health, London

Albert SM, Del Castillo-Castaneda C, Sano M, Jacobs DM, Marder K, Bell K et al (1996) Quality of life in patients with Alzheimer’s disease as reported by patient proxies. J Am Geriatr Soc 44(11):1342–1347

Wu Y-T, Clare L, Jones IR, Martyr A, Nelis SM, Quinn C et al (2018) Inequalities in living well with dementia—the impact of deprivation on well-being, quality of life and life satisfaction: results from the improving the experience of dementia and enhancing active life study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 33(12):1736–1742

Rubin DB (1996) Multiple imputation after 18+ years (with discussion). J Am Stat Assoc 91:473

Britton E, Kindermann G, Domegan C, Carlin C (2020) Blue care: a systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promot Int 35(1):50–69

Gebel K, Bauman AE, Sugiyama T, Owen N (2011) Mismatch between perceived and objectively assessed neighborhood walkability attributes: prospective relationships with walking and weight gain. Health Place 17:519–524

Wu Y-T, Jones NR, van Sluijs EM, Griffin SJ, Wareham NJ, Jones AP (2016) Perceived and objectively measured environmental correlates of domain-specific physical activity in older English adults. J Aging Phys Act 24:599–616

Peters M, Muellmann S, Christianson L, Stalling I, Bammann K, Drell C, Forberger S (2020) Measuring the association of objective and perceived neighborhood environment with physical activity in older adults: challenges and implications from a systematic review. Int J Health Geogr 19(1):47

Dadvand P, Bartoll X, Basagaña X, Dalmau-Bueno A, Martinez D, Ambros A, Cirach M, Triguero-Mas M, Gascon M, Borrell C, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ (2016) Green spaces and general health: roles of mental health status, social support, and physical activity. Environ Int 91:161–167

Parra DC, Gomez LF, Sarmiento OL, Buchner D, Brownson R, Schimd T, Gomez V, Lobelo F (2010) Perceived and objective neighborhood environment attributes and health related quality of life among the elderly in Bogotá, Colombia. Soc Sci Med 70(7):1070–1076

Fongar C, Aamodt G, Randrup TB, Solfjeld I (2019) Does perceived green space quality matter? Linking Norwegian adult perspectives on perceived quality to motivation and frequency of visits. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(13):2327

Gruebner O, Rapp MA, Adli M, Kluge U, Galea S, Heinz A (2017) Cities and mental health. Dtsch Arztebl Int 114(8):121–127

White H, Shah P (2019) Attention in urban and natural environments. Yale J Biol Med 92(1):115–120

Raanaas RK, Patil GG, Hartig T (2012) Health benefits of a view of nature through the window: a quasi-experimental study of patients in a residential rehabilitation center. Clin Rehabil 26(1):21–32

Alzheimer Disease International (2015) Dementia Friendly Communities (DFCs). New domains and global examples. Alzheimer Disease International, London. https://www.alz.co.uk/adi/pdf/dementia-friendly-communities.pdf. Accessed 26 Mar 2020

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the three UK research networks, the NIHR Clinical Research Network in England, the Scottish Dementia Network (SDN) and Health and Care Research Wales, for supporting the study. We thank the local principal investigators and staff at our NHS sites, the IDEAL study participants and their families, the members of the ALWAYs group and the Project Advisory Group.

Funding

‘Improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life: living well with dementia. The IDEAL study’ was funded jointly by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through Grant ES/L001853/2. Investigators: L. Clare, I. R. Jones, C. Victor, J. V. Hindle, R. W. Jones, M. Knapp, M. Kopelman, R. Litherland, A. Martyr, F. Matthews, R. G. Morris, S. M. Nelis, J. Pickett, C. Quinn, J. Rusted, J. Thom. ESRC is part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). ‘Improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life: a longitudinal perspective on living well with dementia. The IDEAL-2 study’ is funded by Alzheimer’s Society, grant number 348, AS-PR2-16-001. Investigators: L. Clare, I. R. Jones, C. Victor, C. Ballard, A. Hillman, J. V. Hindle, J. Hughes, R. W. Jones, M. Knapp, R. Litherland, A. Martyr, F. Matthews, R. G. Morris, S. M. Nelis, C. Quinn, J. Rusted. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the ESRC, UKRI, NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, the National Health Service, or Alzheimer’s Society. The support of ESRC, NIHR and Alzheimer’s Society is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

YTW and IRJ developed the original idea and designed the approach. YTW conducted the data analysis and FEM supervised the analysis. YTW wrote the first draft and all authors contributed to manuscript writing and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no competing interest.

Ethics approval

The IDEAL study was approved by the Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 (reference 13/WA/0405) and the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, Bangor University (reference 2014-11684).

Consent to participate

The IDEAL study obtained written informed consent from participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

The analysis codes are available via contacting the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, YT., Clare, L., Jones, I.R. et al. Perceived and objective availability of green and blue spaces and quality of life in people with dementia: results from the IDEAL programme. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56, 1601–1610 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02030-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02030-y