Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about consumer information needs regarding antipsychotic medicines. Medicines call centre (MCC)-derived data are underutilised; and could provide insight into issues of importance to consumers. This study aimed to explore consumers’ information needs about antipsychotic medication sought from a national MCC in Australia.

Methods

Questions received by the National Prescribing Service Medicines Line relating to antipsychotic medication from September 2002 to June 2010 were examined by antipsychotic subclass and in relation to other medication queries.

Results

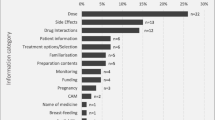

We identified 6,295 calls related to antipsychotic medication. While female callers predominated, the percentage of males with antipsychotic questions was statistically significantly higher than for other medication calls (33.9 vs 22.6 %; p < 0.001). There were distinct gender differences in medicines information seeking across age ranges. Younger men asked about second-generation antipsychotics, shifting toward first-generation antipsychotics after 45 years of age. Female interest in both subclasses was comparable, irrespective of age. Most callers asking about antipsychotics sought information for themselves (69.4 %). Callers were primarily concerned about safety (57.0 %), especially adverse drug reactions (28.8 %), and were more often prompted by a worrying symptom (23.8 %) compared with the rest of calls (17.2 %). Trends of antipsychotic questions received corresponded with antipsychotic prescription data.

Conclusions

The number of calls received by this MCC over time reveals an ongoing consumer need for additional, targeted information about antipsychotics. Noticeable was the relatively high frequency of young male callers asking about antipsychotics, indicating that call centres could be a way to reach these traditionally poor users of health services.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organisation (2001) The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health—New Understanding, New Hope. World Health Organisation, Geneva

Rössler W, Joachim Salize H, van Os J, Riecher-Rössler A (2005) Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15(4):399–409

Mental health services in Australia (2012) Mental-health related prescriptions. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. http://mhsa.aihw.gov.au/resources/prescriptions/. Accessed 8 Dec 2012

Data and Modelling Section Pharmaceutical Policy and Analysis Branch (2011) Expenditure and prescriptions twelve months to 30 June 2011. Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme. http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/statistics/expenditure-and-prescriptions-30-06-2011. Accessed 21 Jan 2013

Verdoux H, Tournier M, Begaud B (2010) Antipsychotic prescribing trends: a review of pharmaco-epidemiological studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 121(1):4–10. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01425.x

Tio J, LaCaze A, Cottrell WN (2007) Ascertaining consumer perspectives of medication information sources using a modified repertory grid technique. Pharm World Sci 29(2):73–80

Närhi U (2007) Sources of medicine information and their reliability evaluated by medicine users. Pharm World Sci 29(6):688–694

Ho CH, Ko Y, Tan ML (2009) Patient needs and sources of drug information in Singapore: is the Internet replacing former sources? Ann Pharmacother 43(4):732–739. doi:10.1345/aph.1L580

Melnyk P, Shevchuk Y, Remillard A (2000) Impact of the dial access drug information service on patient outcome. Ann Pharmacother 34(5):585–592

Bertsche T, Hammerlein A, Schulz M (2007) German national drug information service: user satisfaction and potential positive patient outcomes. Pharm World Sci 29(3):167–172

Marvin V, Park C, Vaughan L, Valentine J (2011) Phone calls to a hospital medicines information helpline: analysis of queries from members of the public and assessment of potential for harm from their medicines. Int J Pharm Pract 19(2):115–122. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7174.2010.00081.x

Svarstad BL, Mount JK, Tabak ER (2005) Expert and consumer evaluation of patient medication leaflets provided in US pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc 45:443–451

Dutta-Bergman MJ (2003) Developing a profile of consumer intention to seek our health information beyond a doctor. Health Mark Q 21(1–2):91–112

Lambert SD, Loiselle CG (2007) Health information-seeking behavior. Qual Health Res 17(8):1006–1019

Anker AE, Reinhart AM, Feeley TH (2011) Health information seeking: a review of measures and methods. Patient Educ Couns 82(3):346–354. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.008

World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (2010) Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment, 2011. World Health Organisation, Oslo

UBM Medica (2012) MIMS. MIMS Australia. http://www.mims.com.au/index.php/about-mims/mims-australia. Accessed 27 Sep 2012

ABS (2009) National Health Survey: Summary of Results, 2007-2008. Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mf/4364.0 Accessed 21 Jan 2013

Information and Research Branch Department of Health and Aged Care (2001) Measuring Remoteness: Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA) New Series, vol 14. Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing (2004–2012) Australian statistics on medicines 2002-2010. Department of Health and Ageing. http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/browse/statistics. Accessed 4 Feb 2013

ABS (2012) Year Book Australia 2012; population and growth 2010. Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1301.0. Accessed 11 Feb 2013

ABS (2007) Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) Remoteness Structure (RA) Digital Boundaries, Australia, 2006. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra

Smith JA, Braunack-Mayer A, Wittert G (2006) What do we know about men’s help-seeking and health service use? Med J Aust 184(2):81–83

Warner D, Procaccino JD (2004) Toward wellness: Women seeking health information. J Am Soc Inform Sci Technol 55(8):709–730

Pohjanoksa-Mantyla MK, Antila J, Eerikainen S, Enakoski M, Hannuksela O, Pietila K, Airaksinen M (2008) Utilization of a community pharmacy-operated national drug information call center in Finland. Res Social Adm Pharm 4(2):144–152. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.05.001

Huber M, Kullak-Ublick GA, Kirch W (2009) Drug information for patients—an update of long-term results: type of enquiries and patient characteristics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 18(2):111–119. doi:10.1002/pds.1682

Gourash N (1978) Help-seeking: a review of the literature. Am J Community Psychol 6(5):413–423

Ramanadhan S, Viswanath K (2006) Health and the information nonseeker: a profile. Health Commun 20(2):131–139

Mackenzie CS, Gekoski WL, Knox VJ (2006) Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: the influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Ment Health 10(6):574–582

Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun TB (2007) Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20(4):359–364

Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P (2005) Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs 49(6):616–623

Biddle L, Gunnell D, Sharp D, Donovan JL (2004) Factors influencing help seeking in mentally distressed young adults: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract 54(501):248–253

Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä M, Bell JS, Helakorpi S, Närhi U, Pelkonen A, Airaksinen M (2011) Is the Internet replacing health professionals? A population survey on sources of medicines information among people with mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46(5):373–379. doi:10.1007/s00127-010-0201-7

Powell J, Clarke A (2006) Internet information-seeking in mental health. Br J Psychiatry 189(3):273–277

Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Cochand S, Hoch A, Khankarli MB, Khan R, Zullino DF (2008) Internet use by patients with psychiatric disorders in search for general and medical informations. Psychiatr Q 79(4):301–309. doi:10.1007/s11126-008-9083-1

McGuire TM (2005) Consumer medicines call centres: a medication liaison model of pharmaceutical care. Dissertation, University of Queensland

Rosen NO, Knäuper B (2009) A little uncertainty goes a long way: State and trait differences in uncertainty interact to increase information seeking but also increase worry. Health Commun 24(3):228–238. doi:10.1080/10410230902804125

Happell B, Manias E, Roper C (2004) Wanting to be heard: mental health consumers’ experiences of information about medication. Int J Ment Health Nurs 13(4):242–248

Powell J, Clarke A (2006) Information in mental health: qualitative study of mental health service users. Health Expect 9(4):359–365

Gray R, Rofail D, Allen J, Newey T (2005) A survey of patient satisfaction with and subjective experiences of treatment with antipsychotic medication. J Adv Nurs 52(1):31–37

Weiden PJ, Buckley PF (2007) Reducing the burden of side effects during long-term antipsychotic therapy: the role of “switching” medications. J Clin Psychiatry 68(6):14–23

Eysenbach G, Diepgen TL (1999) Patients looking for information on the internet and seeking teleadvice: motivation, expectations, and misconceptions as expressed in e-mails sent to physicians. Arch Dermatol 135(2):151–156

Umefjord G, Petersson G, Hamberg K (2003) Reasons for consulting a doctor on the Internet: Web survey of users of an Ask the Doctor service. J Med Internet Res 5(4):e26

Newby DA, Hill SR, Barker BJ, Drew AK, Henry DA (2001) Drug information for consumers: should it be disease or medication specific? Results of a community survey. Aust N Z J Public Health 25(6):564–570

Grymonpre R, Steele J (1998) The medication information line for the elderly: an 8-year cumulative analysis. Ann Pharmacother 32(7):743–748

Fleischhacker WW, Meise U, Günther V, Kurz M (1994) Compliance with antipsychotic drug treatment: influence of side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 382:11–15

Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J (2001) Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther 26(5):331–342

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge NPS MedicineWise (formerly National Prescribing Service, Australia), funder of NPS Medicines Line and service provider since July 2010. We would also like to thank Mater Health Services for providing the raw service data from September 2002 to 30 June 2010; and Gabrielle Hartley, Mater Pharmacy Services, for database assistance. This study was supported by a travel scholarship for Rianne Weersink from the Chiel Hekster Fund and the Stipendium Fund of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij ter bevordering der Pharmacie (KNMP), The Netherlands.

Conflict of interest

The sponsors had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weersink, R.A., Taxis, K., McGuire, T.M. et al. Consumers’ questions about antipsychotic medication: revealing safety concerns and the silent voices of young men. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50, 725–733 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-1005-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-1005-y