Abstract

Purpose

This study examined the effects of individual and regional characteristics on receiving depression-specific treatment in the statutory health-insured population of Bavaria (83% of the population).

Methods

Data of the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians in Bavaria were analysed for prevalence, diagnosis of and treatment for depression in outpatient care by considering individual and regional characteristics.

Results

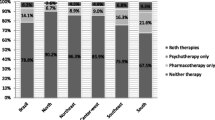

Prevalence of diagnosed depression was 9.2% for the statutory health-insured population aged 18–100 years. More than half of all individuals diagnosed with depression (F32.x/F33.x) and more than one-third of persons diagnosed with severe depression (F32.2/.3 and F33.2/.3) did not receive depression-specific treatment. Rates of a depression-specific treatment were higher for females, the middle aged, individuals with more severe depression diagnoses, those with psychiatric comorbidity and those without physical comorbidity and for individuals living in more rural areas.

Conclusions

The pathways to depression-specific treatment for persons diagnosed with moderate and severe depression need to be improved. Training for physicians, stepped care approaches, psycho-education for patients and anti-stigma campaigns are possible measures to reach this goal. The knowledge on individual characteristics that influence receiving a depression-specific treatment is important to target the groups at increased risk for under-treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S et al (2004) Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 109:21–27

Wittchen H-U, Jacobi F (2005) Size and burden of mental disorders in Europe—a critical review and appraisal of 27 studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15(4):357–376

Jacobi F, Klose M, Wittchen H-U (2004) Mental disorders in the community: healthcare utilization and disability days. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 47(8):736–744

Bramesfeld A, Grobe T, Schwartz FW (2007) Who is treated, and how, for depression? An analysis of statutory health insurance data in Germany. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42(9):740–746

Bramesfeld A, Grobe T, Schwartz FW (2010) Prevalence of depression diagnosis and prescription of antidepressants in East and West Germany: an analysis of health insurance data. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45:329–335

Friemel S, Bernert S, Angermeyer MC, König HH (2005) The direct costs of depressive disorders in Germany. Psychiatr Prax 32(3):113–121

Mathers CD, Lopez AD, Murray CJL (2006) The burden of disease and mortality by condition: data, methods, and results for 2001. In: Lopez AD et al. (eds) Global burden of disease

Gesundheitswesen. In: Statistical yearbook 2008 for the Federal Republic of Germany. Wiesbaden

Wang JL (2004) Rural-urban differences in the prevalence of major depression and associated impairment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39:19–25

Hu T, He Y, Zhang M, Chen N (2007) Economic costs of depression in China. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42:110–116

Thase ME, Friedman ES, Biggs MM et al (2007) Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second-step treatments: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 164(5):739–752

DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD et al (2005) Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(4):409–416

Casacalenda N, Perry JC, Looper K (2002) Remission in major depressive disorder: a comparison of pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and control conditions. Am J Psychiatry 159(8):1354–1360

DeRubeis RJ, Gelfand LA, Tang TZ, Simons AD (1999) Medications versus cognitive behavior therapy for severely depressed outpatients: mega-analysis of four randomized comparisons. Am J Psychiatry 156(7):1007–1013

Mojtabai R, Olfson M (2006) Treatment seeking for depression in Canada and the United States. Psychiatr Serv 57(5):631–639

Parikh SV, Lesage AD, Kennedy SH, Goering PN (1999) Depression in Ontario: under-treatment and factors related to antidepressant use. J Affect Disord 52(1–3):67–76

Fernandez A, Haro JM, Martinez-Alonso M et al (2007) Treatment adequacy for anxiety and depressive disorders in six European countries. Br J Psychiatry 190:172–173

Wittchen H-U, Schuster P, Pfister H, Muller N, Storz S, Isensee B (1999) Depressive disorders in the general population—poorly recognized and rarely treated. Nervenheilkunde 18(4):202–209

Spijker J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Nolen WA (2001) Care utilization and outcome of DSM-III-R major depression in the general population. Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Acta Psychiatr Scan 104(1):19–24

Kessler RC, Zhao SY, Katz SJ et al (1999) Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the national comorbidity survey. Am J Psychiatry 156(1):115–123

Rost K, Zhang ML, Fortney J, Smith J, Smith GR (1998) Rural-urban differences in depression treatment and suicidality. Med Care 36(7):1098–1107

Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Warden D et al (2008) Selecting among second-step antidepressant medication monotherapies Predictive value of clinical, or first-step treatment features. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65(8):870–881

Gesetzliche Krankenversicherungen: Kennzahlen und Faustformeln, 2009

Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC (2005) Twelve-month use of Mental Health Services in the United States—results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(6):629–640

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O et al (2003) The epidemiology of major depressive disorder—results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289(23):3095–3105

Karasu TB, Gelenberg A, Merriam A, Wang P (2000) Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, 2nd edn. American Psychiatric Association Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/loadGuidelinePdf.aspx?file=MDD2e_05-15-06

Management of Moderate to Severe Depression. http://www.gacguidelines.ca/index.cfm?ACT=topics&Summary_ID=216&Topic_ID=23 2007

Management of Mild Depression. http://www.gacguidelines.ca/index.cfm?ACT=topics&Summary_ID=215&Topic_ID=23 2007

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2004) Depression: management of depression in primary and secondary care—National Clinical Practice Guideline Number 23: The British Psychological Society and Gaskell

Hedeker DA (2003) Mixed-effects multinomial logistic regression model. Stat Med 22(9):1433–1446

Heck RH. (2001) Multilevel Modeling with SEM. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE (eds) New developments and techniques in structural equation modeling. Erlbaum, Mahwah

Heck RH, Thomas SL (2009) An introduction to multilevel modeling techniques. 2nd (edn). Quantitative methodology series. Routledge, New York

Muthen LK, Muthen BO (2007) Mplus user’s guide, 5th edn. Muthén & Muthén, CA

S3-Leitlinie/Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie Unipolare Depression: Langfassung, 1st edn. Berlin; Düsseldorf; 2009

Palsson SP, Ostling S, Skoog I (2001) The incidence of first-onset depression in a population followed from the age of 70 to 85. Psychol Med 31(7):1159–1168

Hegerl U, Althaus D, Schmidtke A, Niklewski G (2006) The alliance against depression: 2-year evaluation of a community-based intervention to reduce suicidality. Psychol Med 36(9):1225–1233

van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Smits N (2008) Effectiveness of a web-based self-help intervention for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 10(1):e7

Veer-Tazelaar PJ Van’t; Marwijk HW Van, Oppen P Van et al (2009) Stepped-care prevention of anxiety and depression in late life: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66(3):297–304

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians Bavaria, Munich, Germany.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boenisch, S., Kocalevent, RD., Matschinger, H. et al. Who receives depression-specific treatment? A secondary data-based analysis of outpatient care received by over 780,000 statutory health-insured individuals diagnosed with depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47, 475–486 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0355-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0355-y