Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The aim of this study was to investigate whether the use of antimicrobials is associated with the risk of childhood type 1 diabetes.

Materials and methods

The study population included all children born in Finland between 1996 and 2000 who were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes by the end of 2002. For each case (n=437), four matched controls were selected. Data on diabetes and the maternal use of antimicrobials was derived from nationwide registries.

Results

Maternal use of phenoxymethyl penicillins (odds ratio [OR]=1.70, 95% CI 1.08–2.68, p=0.022) or quinolone antimicrobials (OR=2.43, 95% CI 1.16–5.10, p=0.019) before pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of type 1 diabetes in the child, whereas the use of other specific antimicrobials was not related to the risk. The risk was also higher among mother–child pairs where macrolides were used both by the mother before pregnancy and by the child, compared with pairs where neither used macrolides (OR=1.76, 95% CI 1.05–2.94, p=0.032). Maternal use of antimicrobials during pregnancy was not associated with an increased risk. The high use of antimicrobials by the child (more than seven vs seven or less purchases) was related to greater risk (OR=1.66, 95% CI 1.24–2.24, p=0.001).

Conclusions/interpretation

Overall, the use of antimicrobials before pregnancy, during pregnancy or during childhood was not related to the risk of childhood type 1 diabetes. However, the use of some specific antimicrobials by the mother before pregnancy and by the child may be associated with an increased risk. Further studies are needed to confirm these associations and to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes is considered to be a chronic immune-mediated disease that is characterised by the destruction of insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. Low concordance rates among monozygotic twins, the results of migrant studies, a large international variation in incidence, and increasing worldwide incidence rates suggest that environmental factors play a critical role in the development of this disease [1]. The relatively young age at onset and the long preclinical phase of type 1 diabetes suggest that these environmental risk factors may play a role in the foetal or perinatal period of life, when the immune system is maturing [1]. Exposure to microbes and the immunological consequences of infection may be involved in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Within this context, the treatment of infections by using antimicrobials could also play a role as either an indicator of exposure to microbes; via effects on intestinal flora (e.g. disturbing the maturation of the immune system); or via direct toxic effects on beta cells. We investigated whether the use of antimicrobials by the mother or by the child was associated with the risk of type 1 diabetes in Finnish children born between 1996 and 2000.

Subjects and methods

Subjects and data collection

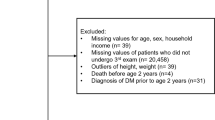

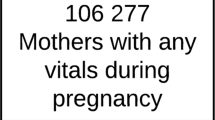

This study is based on registers confirmed to have high validity and coverage [2]. The study population was derived from a birth cohort consisting of all births in Finland between 1996 and 2000. Of these, 450 children were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes by the end of 2002. Cases were identified from the national register based on special reimbursement for drug costs. Patients with a certificate from a physician stating that the diagnostic criteria of type 1 diabetes are fulfilled are entitled to reimbursement of the drug costs. Thirteen children who had not purchased any insulin (who were probably mistakenly diagnosed with diabetes) were excluded. For each case, four non-diabetic controls who were matched to the case in terms of age (±28 days), sex and hospital district were randomly selected from the population register.

Information on antimicrobial use was obtained from a nationwide drug prescription register. All antimicrobials purchased by a mother during the year preceding pregnancy and during the pregnancy, and for the child from birth until the time the case was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, were included. The data were completed by linkage with the Finnish Medical Birth Register; no data were available for ten subjects. The linkages were based on the unique personal identification numbers of the mothers and children. The study was approved by the National Data Protection Ombudsman, the institutions keeping the registers, and the Institutional Review Board of the National Public Health Institute.

Statistical analysis

To examine case–control differences in background characteristics the Cuzick non-parametric test for trend across ordered groups (categories of maternal socio-economic status, parity, and age and quartiles of ponderal index and gestational age), the χ2 test (maternal smoking), Fisher’s exact test (maternal type 1 diabetes) and ANOVA (continuous variables) were used. The conventional contingency table χ2 test was used to examine case–control differences in the prevalence of antimicrobial use, to evaluate whether the prevalence of antimicrobial use was associated with background characteristics and whether maternal antimicrobial use was associated with that of the child. The associations between use of antimicrobials and the risk of type 1 diabetes were analysed using conditional logistic regression with and without an adjustment for the background variables with case–control differences (p<0.1), i.e. maternal smoking, maternal type 1 diabetes, gestational age and mode of delivery. Two-sided p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The present study included 437 cases (218 boys and 219 girls, mean age at diagnosis 2.7 years, range 47 days to 5.7 years) with type 1 diabetes and 1,748 control children. The prevalence of antimicrobial use was the same in cases and controls in mothers before pregnancy (33 vs 34%, respectively), in mothers during pregnancy (24 vs 25%, respectively) and in children (76 vs 78%, respectively). The prevalence of maternal antimicrobial use was higher among smokers than non-smokers (p=0.001) and increased according to number of previous births (p<0.0001). Antimicrobials were more often used by children who had older siblings (p<0.0001) and by children of smoking mothers (p=0.041).

The total numbers of antimicrobial prescriptions for the mothers before and during pregnancy and for the children were 1,172, 766 and 8,253, respectively. Antimicrobial prescriptions for the children were distributed evenly over the time preceding the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. The maternal use of antimicrobials overall, as well as the use of cephalosporins, macrolides and penicillins with extended spectrum either before or during pregnancy, was associated with the child’s use of the respective antimicrobials.

Maternal use of phenoxymethyl penicillins (odds ratio [OR]=1.70, 95% CI 1.08–2.68, p=0.022) or quinolone antimicrobials (OR=2.43, 95% CI 1.16–5.10, p=0.019) before pregnancy was associated with the risk of type 1 diabetes in the child when adjusted for the potential confounders (Fig. 1), whereas the use of other specific antimicrobials was not related to the risk. The risk of type 1 diabetes in the child was also greater among pairs where macrolides were used both by the mother before pregnancy and by the child than in pairs where neither used macrolides (OR=1.76, 95% CI 1.05–2.94, p=0.032). Maternal use of antimicrobials during pregnancy was not associated with an increased risk. The high use of antimicrobials by the child was related to a greater risk of type 1 diabetes (OR for more than seven vs seven or less purchases 1.66, 95% CI 1.24–2.24, p=0.001; and OR for more than seven purchases vs zero purchases 1.37, 95% CI 0.94–1.99; Fig. 2).

Discussion

Our findings from a prospective population-based birth cohort covering the whole of Finland suggest, for the first time, that the use of antimicrobials by the mother before pregnancy and by the child may be associated with an increased risk of type 1 diabetes in the child. Because of issues of multiplicity, however, these results should be regarded as no more than borderline statistically significant. One possible explanation for a putative effect is that the use of antimicrobials serves as an indicator of infections possibly involved in pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes [1]. The use of antimicrobials, especially of those with a broad antibacterial spectrum and those that are incompletely absorbed, induces marked changes in gut flora [3]. This may not only disturb the maturation of the immune system, but may also make the gut more vulnerable to other environmental triggers. The favourable effects of the human normal microflora on the immune system are believed to be mainly associated with Bifidobacterium spp. or certain species of the lactic acid bacteria Lactobacillus spp. and Lactococcus spp. [4], i.e. genera extremely sensitive to macrolides, quinolones and penicillins. Maternal use of antimicrobials may prevent or delay the transmission of this normal microflora from the mother to the child. Certain antimicrobials may have direct toxic effects on beta cells. Because of the structural and functional similarities between bacteria and human mitochondria, exposure to macrolides and quinolones may inhibit the mitochondrial synthesis of DNA and enzymes in beta cells, resulting in beta cell death [5]. Antimicrobials have been shown to induce apoptosis by different mechanisms in many types of cells [6]. Moreover, bafilomycin A1 (a macrolide not in medical use) induced changes in pancreatic beta cells and dysregulation of insulin secretion in mice [7]. In utero exposure to bafilomycin (12 μg/kg) accelerated the onset of immune-mediated diabetes in NOD mice [8]. Unexpectedly, the maternal use of quinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and norfloxacin), phenoxymethyl penicillins or macrolides (azithromycin, clarithromycin and roxithromycin) before pregnancy was related to the risk of type 1 diabetes in the child. The macrolides used in our birth cohort are lipophilic and become concentrated in body fats and tissues to levels that greatly exceed those in plasma [9]. Quinolones complex with calcium, accumulate in bone [10], and remobilise when calcium is mobilised, such as during pregnancy or lactation. Since both these antimicrobials have a high placental passage [11, 12], mobilisation of maternal body deposits could explain the observed positive association between the use of macrolides or quinolones during the 12 months before pregnancy and the risk of type 1 diabetes in the child.

To conclude, we have shown, in a well-defined nationwide cohort, using validated sources of information on drug use and diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, that the use of antimicrobials by the mother before pregnancy and by the child may be associated with an increased risk of type 1 diabetes in the child. It cannot be determined from this study whether the use of antimicrobials is causally related to type 1 diabetes, whether the indication for antimicrobial use weakened overall immune function, or if other factors are the pertinent underlying causes. Although further studies are needed to establish the associations and possible underlying mechanisms of action, these findings reinforce the need for prudent use of antimicrobials.

Abbreviations

- OR:

-

odds ratio

References

Knip M, Veijola R, Virtanen S, Hyöty H, Vaarala O, Åkerblom H (2005) Environmental triggers and determinants of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 54(Suppl 2):S125–S136

Gissler M, Teperi J, Hemminki E, Merilainen J (1995) Data quality after restructuring a national medical registry. Scand J Soc Med 23:75–80

Sullivan A, Edlund C, Nord CE (2001) Effect of antimicrobial agents on the ecological balance of human microflora. Lancet Infect Dis 1:101–114

Kimura K, McCartney AL, McConnell MA, Tannock GW (1997) Analysis of fecal populations of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli and investigation of the immunological responses of their human hosts to the predominant strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:3394–3398

Hayem G, Petit PX, Levacher M, Gaudin C, Kahn MF, Pocidalo JJ (1994) Cytofluorometric analysis of chondrotoxicity of fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 38:243–247

Jun YT, Kim HJ, Song MJ et al (2003) In vitro effects of ciprofloxacin and roxithromycin on apoptosis of jurkat T lymphocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:1161–1164

Myers MA, Mackay IR, Rowley MJ, Zimmet PZ (2001) Dietary microbial toxins and type 1 diabetes—a new meaning for seed and soil. Diabetologia 44:1199–1200

Hettiarachchi KD, Zimmet PZ, Myers MA (2004) Transplacental exposure to bafilomycin disrupts pancreatic islet organogenesis and accelerates diabetes onset in NOD mice. J Autoimmun 22:287–296

Foulds G, Shepard RM, Johnson RB (1990) The pharmacokinetics of azithromycin in human serum and tissues. J Antimicrob Chemother 25(Suppl A):73–82

Rimmele T, Boselli E, Breilh D et al (2004) Diffusion of levofloxacin into bone and synovial tissues. J Antimicrob Chemother 53:533–535

Kim JC, Bae CS, Kim SH et al (2003) Transplacental pharmacokinetics of the new fluoroquinolone DW-116 in pregnant rats. Toxicol Lett 142:103–109

Witt A, Sommer EM, Cichna M et al (2003) Placental passage of clarithromycin surpasses other macrolide antibiotics. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188:816–819

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Academy of Finland (grant 201988) and the Juho Vainio Foundation. We are also grateful to T. Korhonen for skilful technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kilkkinen, A., Virtanen, S.M., Klaukka, T. et al. Use of antimicrobials and risk of type 1 diabetes in a population-based mother–child cohort. Diabetologia 49, 66–70 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-0078-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-0078-2