Abstract

The plant-communities from habitats of the metallophyte species Minuartia verna and Thlaspi alpestre (T. caerulescens) at sites disturbed and undisturbed by mining are described. Four communities were delineated by cluster and principal component analysis. Group 1 comprised species-poor communities on disturbed non-calcareous soils; group 2, relatively species-rich communities on disturbed calcareous soils; group 3, species-rich communities in the main on undisturbed calcareous soils. Group 4 consisted of species-rich communities with an alpine element, in damp habitats on base-rich soils derived from igneous rocks. Total and exchangeable elements As, Ba, Ca, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mg, Mn, Ni, Pb and Zn were determined for the soils of these sites. Levels of soil Ca, Cd, Pb and Zn accounted for most of the variation along the first axis of the PCA and soil nutrient levels were probably the main predictor along the second.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- PCA:

-

Principal Component Analysis

References

Allen S. E., Grimshaw M. H., Parkinson J. A. & Quarmby C. 1974. Chemical analysis of ecological materials. Blackwell's Scientific Publications, Oxford.

Antonovics J., Bradshaw A. D. & Turner R. G. 1971. Heavy metal tolerance in plants. Adv. Ecol. Res. 7: 1–85.

Barry S. A. S. & Clark S. C. 1978. Problems of interpreting the relationship between the amounts of lead and zinc in plants and soil on metalliferous wastes. New Phytol. 81: 773–783.

Berrow, M. L. & Burridge, J. C. 1977. Trace element levels in soils: effects of sewage sludge. In: Inorganic pollution and agriculture, MAFF/ADAS, Reference book 326, pp. 159–183.

Birse E. L. 1982. Plant communities on serpentine in Scotland. Vegetatio 49: 141–162.

Brooks R. R., Shaw S. & Asensi Marfil A. 1981. Some observations on the ecology, metal uptake and nickel tolerance of Alyssum serpyllifolium subspecies from the Iberian peninsula. Vegetatio 45: 183–188.

Dagnelie P. 1975. Analyse statistique à plusieurs variables. Presses Agronomique, Gembloux.

Davies B. E. 1971. Trace metal content of soils affected by base metal mining in the west of England. Oikos 22: 366–372.

Davis J. C. 1973. Statistics and data analysis in geology. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Duvigneaud P. & Denaeyerde Smet 1963. Cuivre et végétation au Katanga. Bull. Soc. Roy. Bot. Belg. 96: 93–231.

Ernst W. 1968a. Ökologische Untersuchungen an Pflanzengesellschaften unterschiedlich stark gestörter schwermetallreicher Böden in Grossbritannien. Flora B 158: 95–109.

Ernst W. 1968b. Zur Kenntnis der Soziologie und Ökologie der Schwermetallvegetation Grossbritanniens. Ber. Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 81: 116–124.

Ernst W. 1974. Schwermetallvegetation der Erde. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart.

Ernst W. 1976. Physiological and biochemical aspects of metal tolerance. In: Mansfield T. A. (ed.) Effects of air pollutants on plants, pp. 115–133. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Ernst W. 1976. Violetea calaminariae. Prodrome of the European plant communities no. 3, pp. 1–132. J. Cramer, Vaduz.

Hawksworth D. L., James P. W. & Coppins B. J. 1980. Checklist of British lichen forming lichenicolous and allied fungi. Lichenologist 12: 1–115.

Hickey D. A. & McNeilly T. 1975. Competition between metal tolerant and normal plant populations: a field experiment on normal soil. Evolution 29: 458–464.

Ingrouille M. J. & Smirnoff N. 1986. Thlaspi caerulescens J. & C. Presl. (T. alpestre) in Britain. New Phytol. 102: 219–233.

Koenigs R. L., Williams W. A. & Jones M. B. 1982. Factors affecting vegetation on a serpentine soil. I. Principal Components Analysis of vegetation data. Hilgardia 50: 1–14.

Kruckeberg A. R. 1954. The ecology of Serpentine soils III. Plant species in relation to Serpentine soils. Ecology 35: 267–274.

Lambinon J. & Auquier P. 1963. La flore et la végétation de terrains calaminaires de la Wallonie septentrionale et de la Rhenanie aixoise. Types chorologiques et groups écologique. Natura Mosana 16: 113–131.

Morrey D. R., Baker A. J. M. & Cooke J. A. 1988. Floristic variation in plant communities on metalliferous mining residues in the northern and southern Pennines, England. Environ. Geochem. Health 10: 11–20.

Motyka J., Dobrzanski B. & Zawadski S. 1950. Wstepne badania nad lakami poludniowo-wschodneij Lubelszczyzny. Ann. Univ. M. Curie-Sklodowska. E. 5: 367–447.

Nicholls M. K. & McNeilly T. 1985. The performance of Agrostis capillaris genotypes differing in Cu tolerance in ryegrass swords on normal soil. New Phytol. 101: 207–217.

Shimwell D. W. & Laurie A. E. 1972. Lead and zinc contamination of vegetation in the South Pennines. Environ. Pollut. 3: 291–301.

Simon E. 1978. Heavy metals in soils, vegetation development and heavy metal tolerance in plant populations from metalliferous areas. New Phytol. 81: 175–188.

Smith R. A. H. & Bradshaw A. D. 1970. The reclamation of toxic metalliferous wastes using tolerant populations of grass. Nature (London) 227: 376–377.

Smith R. A. H. & Bradshaw A. D. 1979. The use of metal tolerant plant populations for the reclamation of metalliferous wastes. J. Appl. Ecol. 16: 595–612.

Sokal R. R. & Michener C. D. 1958. A statistic method for evaluating systematic relationships. Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull. 38: 1409–1438.

Sörensen T. 1948. A method of establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similarity of species content. K. Dan. Vidensk. Selsk., Biol. Skr. 5: 1–34.

Steel R. G. D. & Torrie J. H. 1960. Principles and procedures of statistics. McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc., London.

Thompson J. & Proctor J. 1983. Vegetation and soil factors on a heavy metal mine spoil heap. New Phytol. 94: 297–308.

Walker B. H. & Wehrhann 1971. Relationships between derived vegetation gradients and measured environmental variables in Saskatchewan Wetlands. Ecology 52: 85–95.

Wilson J. B. 1988. The cost of heavy-metal tolerance: an example. Evolution 42: 408–413.

Woolhouse H. W. 1983. Toxicity and tolerance in the responses of plants to metals. In: Lange O. L., Nobel P. S., Osmond C. S. & Zeigler H. (eds), Physiological plant ecology III. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Wu L., Bradshaw A. D. & Thurman D. A. 1975. The potential for evolution of heavy metal tolerances. III. The rapid evolution of copper tolerance in Agrostis stolonifera. Heredity 34: 165–187.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

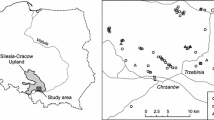

García-Gonzalez, A., Clark, S.C. The distribution of Minuartia verna and Thlaspi alpestre in the British Isles in relation to 13 soil metals. Vegetatio 84, 87–98 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00036509

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00036509