Abstract

In this study, we investigate to what extent macro-economic circumstances and social protection expenditure affect economic deprivation. We use three items from round five of the European Social Survey (2010–2011) to construct our latent outcome variable, which we label economic deprivation in the 3 years before 2010–2011. The results of our linear multilevel regression analyses indicate that in countries that perform worse economically, individual experiences of economic deprivation are more prevalent: the stronger the rise in the unemployment rate and the lower a country’s wealth, the more economic deprivation individuals experience. We also find that in countries with high levels of social protection, people experience less economic deprivation as compared to countries with low levels of social protection. In turn, adverse economic conditions in a country temper these positive outcomes of social welfare arrangements. Finally, our study reveals that the strength of the relationship between a low income and economic deprivation strongly varies according to the economic circumstances in a country and the generosity of the welfare state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine and the United Kingdom. Originally, the data also contained information about individuals in Bulgaria. However, Bulgaria turned out to be an influential case in our measurement invariance analysis: models would not converge. Therefore, we decided to remove Bulgaria from our data.

The correlation between the composite scores and the saved factor scores per country is 0.932. Therefore, we decided to continue with the more easily interpretable composite scores.

Meredith (1993) proposed three types of invariance: (1) Configural, (2) Metric and (3) Scalar. Firstly, configural invariance implies that the measurement model holds across all countries. Secondly, metric invariance implies that configural invariance holds as well as equal factor loadings across all countries. Finally, scalar invariance implies that metric invariance holds and that the indicator intercepts are the same across all countries.

We also ran a model in which we—simultaneously with macro-economic conditions and social protection expenditure—tested if national income inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient) would affect our findings. The results of this sensitivity analysis indicate that the effects at both the individual and country level are stable. Moreover, the effect of income inequality did not prove to be significantly deviating from zero.

Unfortunately, these models would not converge when setting the dummy variables for income to random slope effects. Hence, the individual-level effect of income does not vary across countries in Models 6–10.

To a large extent, the results regarding our hypotheses prove robust if we exclude these countries.

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (2010). IBM SPSS Amos 19 user’s guide. Chicago: SPSS Inc.

Böhnke, P. (2008). Are the poor socially integrated? The link between poverty and social support in different welfare regimes. Journal of European Social Policy, 18, 133–150.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Dearing, J. W., & Rogers, E. (1996). Agenda-setting. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Dewilde, C. (2008). Individual and institutional determinants of multidimensional poverty: a European comparison. Social Indicators Research, 86, 233–256.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Oxford: Polity Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). Social foundations of post-industrial economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eurostat. (2011). ESSPROS manual. The European System of integrated Social PROtection Statistics (ESSPROS). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Gallie, D., & Paugam, S. (Eds.). (2000). Welfare regimes and the experience of unemployment in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., De Graaf, P. M., & Treiman, D. J. (1992). A standard International Socio-Economic Index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 21, 1–56.

Gesthuizen, M., & Scheepers, P. (2010). Economic vulnerability among low-educated Europeans: the impact of resources, the group’s composition, labour market conditions and welfare state arrangements. Acta Sociologica, 53, 247–267.

Gesthuizen, M., Solga, H., & Künster, R. (2011). Context matters: Economic marginalisation of low-educated workers in cross-national perspective. European Sociological Review, 27, 264–280.

Halleröd, B., & Larsson, D. (2008). Poverty, welfare problems and social exclusion. International Journal of Social Welfare, 17, 15–25.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (2006). LISREL 8.80 for Windows [Computer Software]. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International.

Jowell, R., & The Central Coordinating Team. (2007). European Social Survey 2006/2007: Technical report. London: Centre for Comparative Social Surveys, City University.

Keeley, B., & Love, P. (2010). From crisis to recovery: The causes, course and consequences of the Great Recession. Paris: OECD.

Kenworthy, L. (2011). Progress for the poor. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kenworthy, L., Epstein, J., & Duerr, D. (2011). Generous social policy reduces material deprivation. In L. Kenworthy (Ed.), Progress for the poor. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Layte, R., & Whelan, C. T. (2002). Cumulative disadvantage or individualisation? A comparative analysis of poverty risk and incidence. European Societies, 4, 209–233.

Layte, R., Whelan, C. T., Maître, B., & Nolan, B. (2001). Explaining levels of deprivation in the European Union. Acta Sociologica, 44, 105–121.

Lohmann, H. (2009). Welfare states, labour market institutions and the working poor: A comparative analysis of 20 European countries. European Sociological Review, 25, 489–504.

Meredith, W. (1993). Measurement invariance, factor analysis, and factorial invariance. Psychometrika, 58, 525–543.

Mills, M., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2005). Globalization, uncertainty and the early life course: A theoretical framework. In H.-P. Blossfeld, E. Klijzing, M. Milss, & K. Kurz (Eds.), Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society (pp. 1–24). London: Routledge.

Muffels, R., & Fouarge, D. (2004). The role of European welfare states in explaining resources deprivation. Social Indicators Research, 68, 299–330.

Nelson, K. (2012). Counteracting material deprivation: The role of social assistance in Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 22, 148–163.

Nolan, B., Hauser, R., & Zoyem, J. P. (2000). The changing effects of social protection on poverty. In D. Gallie & S. Paugam (Eds.), Welfare regimes and the experience of unemployment in Europe (pp. 87–106). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (1996a). Measuring poverty using income and deprivation indicators: alternatives approaches. Journal of European Social Policy, 6, 225–240.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (1996b). Resources, deprivation and poverty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (2011). Poverty and deprivation in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oberholzer-Gee, F. (2007). Nonemployment stigma as rational herding: a field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 65, 30–40.

OECD. (2008). Growing unequal? Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries. Paris: OECD.

Price, R., Choi, J. N., & Vinokur, A. (2002). Links in the chain of adversity following job loss: how financial strain and loss of personal control lead to depression, impaired functioning, and poor health. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7, 302–312.

Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2009). The aftermath of financial crises. American Economic Review, 99, 466–472.

Saris, W. E., Satorra, A., & Van der Veld, W. M. (2009). Testing structural equation models or detection of misspecifications? Structural Equation Modeling, 16, 561–582.

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: Sage Publishers.

Stuckler, D., Basu, S., Suhrcke, M., Coutts, A., & McKee, M. (2009). The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet, 374, 315–323.

Tsakloglou, P., & Papadopoulos, F. (2002). Aggregate level and determining factors of social exclusion in Twelve European Countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 12, 211–225.

Van der Veld, W. M., Saris, W. E., & Satorra, A. (2008). Judgment Rule Aid for structural equation models. User manual. http://www.vanderveld.nl/SEM/JRule.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4–70.

Whelan, C. T., Layte, R., & Maître, B. (2002). Multiple deprivation and persistent poverty in the European Union. Journal of European Social Policy, 12, 91–105.

Whelan, C. T., Layte, R., & Maître, B. (2003). Persistent income poverty and deprivation in the European Union: An analysis of the first three waves of the European Community Household Panel. Journal of Social Policy, 32, 1–18.

Whelan, C. T., Layte, R., & Maître, B. (2004). Understanding the mismatch between income poverty and deprivation: A dynamic comparative analysis. European Sociological Review, 20, 287–302.

Whelan, C. T., Layte, R., Maître, B., & Nolan, B. (2001). Income, deprivation and economic strain. An analysis of the European Community Household Panel. European Sociological Review, 17, 357–372.

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2005). Economic vulnerability, multidimensional deprivation and social cohesion in an enlarged European community. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 46, 215–239.

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2010). Welfare regime and social class variation in poverty and economic vulnerability. Journal of European Social Policy, 20, 316–332.

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2012). Understanding material deprivation: A comparative European analysis. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30, 489–503.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

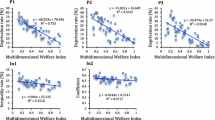

As stated in the data section, we tested if economic deprivation is equivalently measured across our sample of nations. We started by calculating covariance matrices and mean structures for each country separately by importing the original scores on the items into PRELIS. Using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) within LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog and Sörbom 2006), we constructed a single factor, which we labeled ‘economic deprivation in the three years before 2010-2011′ or in short, economic deprivation. Maximum likelihood estimation was used as the procedure to obtain the model parameters. To identify the model, we fixed the factor loading of the item ‘I have had to manage on a lower household income’ to 1. This ensures that the response scale on which this item is measured, is also the scale on which economic deprivation is expressed. We selected this item as our reference variable, because for most people a lower household income represents the most relevant form of economic deprivation.

We then tested our model for three levels of measurement equivalence (i.e., configural, metric and scalar invariance), applying multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA), again within LISREL. Following the approach suggested by Vandenberg and Lance (2000), we employed a bottom-up procedure to detect misspecifications in the MGCFA model, because the number of parameters that are potentially misspecified in the most constrained model (i.e., scalar invariance) in a top-down approach could be overwhelming. Therefore, we started by testing for configural invariance, which is the least constrained model.

The standard procedure to assess whether a constrained parameter is misspecified or not, is by looking at the modification index (MI) and the expected parameter change (EPC). As Saris, Satorra and Van der Veld (2009) showed, however, the power of the test may influence the MI. To solve this issue (thus, to take into account the power of the test), we made use of the software package JRule 3.0.4 (Van der Veld et al. 2008). This program computes judgment rules based on LISREL output, indicating for each parameter if it is misspecified, not misspecified or if it depends on the extent to which the parameter will change when it is not constrained.

The results of our configural invariance test indicate that the measurement model holds across all countries. We also evaluated the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). According to various scholars, a value of the RMSEA of 0.050 or less would indicate a close fit of the model, a value between 0.050 and 0.080 would indicate a reasonable error of approximation and a global model fit greater than 0.100 suggests a poor fit (Arbuckle 2010; Browne and Cudeck 1993; Hu and Bentler 1999). We found a RMSEA of 0.000 (df = 1), indicating a perfect model fit.

For our metric invariance test, we have chosen Poland as our reference country, which has factor loadings close to the average across all counties. A reference country with extreme factor loadings will result in a decreased likelihood of that county being invariant. If we would select a country that is not invariant, it will become harder to compare a large set of countries. For Poland, we estimated the factor loadings, whereas in all other countries the factor loadings are constrained to being invariant. With help of JRule, we evaluated the imposed invariance constraints. Since configural invariance already holds, it makes no sense to look at misspecifications regarding correlated random error terms and correlated unique components. After all, these constrained parameters should have been detected as a misspecification during the configural invariance test. The results of JRule show that we have to inspect some of the EPC’s. There are four factor loadings that would significantly change when estimated, namely λ 21 in Germany and λ 31 in Croatia, Cyprus and Greece. We decided to adjust our model, because the model fit is mediocre: the value of the RMSEA is 0.095. When we released the constraints on these factor loadings, the value of the RMSEA becomes 0.060, almost indicating a close fit.

Given that we already tested for configural and metric invariance, we only evaluated the mean structure of our measurement model in our next step. We already estimated the intercept means of the items of which the factor loadings were released in our metric invariance test. First of all, the results of the scalar invariance test show that the RMSEA is 0.110, which indicates a poor model fit. We decided to adjust our model by looking at the MI in combination with the EPC. Ultimately, we released (in a stepwise manner) the constraints on the intercepts of several indicators in the following countries: ε 1 of item G8 in Cyprus, ε 2 of item G9 in the Czech Republic, ε 2 of item G9 in Estonia and ε 1 of item G8 and ε 3 of item G10 in Finland. After adapting these intercepts, the RMSEA of our model is 0.080. Since this implies reasonable error of approximation and because we would like to avoid partial scalar invariance for other countries, we chose to accept the model. Hence, our final model is partially invariant for Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany and Greece. This results in 7 of the 25 countries (28 percent) being partially invariant. We provide an overview of the factor loadings and indicator intercepts of our final measurement model in Table 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Visser, M., Gesthuizen, M. & Scheepers, P. The Impact of Macro-Economic Circumstances and Social Protection Expenditure on Economic Deprivation in 25 European Countries, 2007–2011. Soc Indic Res 115, 1179–1203 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0259-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0259-1