Abstract

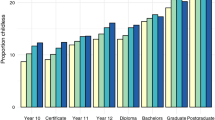

The decline in fertility in Australia in the 1990s reflected both decreased first-order birth rates and decreased second-order birth rates (Kippen 2004). Whilst childlessness has been studied extensively, little attention has been paid to the progression from one to two children. This study analyses which women stop at one child using data from 1,809 parous 40–54 year olds from Wave 1 of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. Important early lifecourse predictors of whether a woman stops her childbearing at one child are shown to be a woman s country of birth, highest level and type of schooling, and her father s occupation. A woman s marital status and her age at the time of the first birth are also shown to be significant predictors of her likelihood of not progressing to a second birth. The causes of trends over time are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abbasi-Shavazi, M.J. and P. McDonald. 2000. Fertility and multiculturalism: immigrant fertility in Australia 1977–1991.International Migration Review 34(1):215–242.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 1997.Australian Standard Classification of Occupations (ASCO) Second Edition. Catalogue Number 1220.0. Canberra.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2003.Schools. Catalogue Number 4221.0. Canberra.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2006a.Births 2005. Catalogue Number 3301.0. Canberra.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2006b.Australian Historical Statistics. Catalogue Number 3105.0.65.001. Canberra.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2006c.Marriages 2005. Catalogue Number 3306.0.55.001.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2007.Australia at a Glance. Catalogue Number 1309.0. Canberra.

Avdeev, A. 2001. How fertility has fallen in Russia and the reasons for the fall. Paper presented to the IUSSP Seminar on International Perspectives on Low Fertility: Trends, Theories and Policies, Tokyo, 21–23 March.

Baird, M. 2005. Who s rocking the cradle?Making the Link 16: 32–38.

Blake, J. 1979. Is zero preferred? American attitudes towards childlessness in the 1970s.Journal of Marriage and the Family 41(May):245–257.

Blake, J. 1989.Family Size and Achievement. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Bongaarts, J. and R.G. Potter. 1983.Fertility, Biology and Behavior. New York: Academic Press.

Breusch, T. and E. Gray. 2004. New estimates of mothers forgone earnings using HILDA data.Australian Journal of Labour Economics 7(2):125–150.

Carmichael. G.A. 1998. Things aint what they used to be! Demography, mental cohorts, morality and values in Post-War Australia.Journal of the Australian Population Association 15(2):91–114.

Carmichael, G.A. and P. McDonald. 2003. Fertility trends and differentials. Pp. 40–76 in S-E. Khoo and P. McDonald (eds),The Transformation of Australia s Population 1970–2030. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Carmichael, G.A. and A. Whittaker. 2007. Choice and circumstance: qualitative insights into contemporary childlessness in Australia.European Journal of Population 23(2):111–143.

Chapman, B., Y. Dunlop, M. Gray, A. Liu and D. Mitchell. 2001. The impact of children on the lifetime earnings of Australian women: evidence from the 1990s.Australian Economic Review 34(4):373–389.

Craig, L. 2003. The time cost of children: a cross-national comparison of the interaction between time use and fertility rate. Paper presented to the 25th IATUR Conference on Time Use Research Comparing Time, Brussels, 17–19 September.

Craig, L. 2005.Where Do They Find the Time? Social Policy Research Centre Discussion Paper No 136. Sydney: UNSW.

Craig, L. 2006. Parental education, time in paid work and time with children: an Australian time-diary analysis.British Journal of Sociology 57(4):553–575.

Craig, L. and M. Bittman. 2003. The time costs of children in Australia. Paper presented to Rethinking Expenditures on Children: Towards an International Research Agenda, ANU, Canberra, 15–16 January.

Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (DIMA). 2001.Immigration: Federation to Century s End. Canberra.

Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (DIMA). 2006.Immigration Update. Canberra.

Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (DIMIA). 2002.Australian Immigration Consolidated Statistics. Canberra.

De Vaus, D., L. Qu and R. Weston. 2005. The disappearing link between premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital stability 1971–2001.Journal of Population Research 22(2):99–118.

Dodson, L. 2004. The mother of all spending sprees.Sydney Morning Herald 12 May: 1.

Fong, V.L. 2004.Only Hope: Coming of Age Under Chinas One-Child Policy. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Greenhalgh, S. 2003. Science, modernity and the making of China s one-child policy.Population and Development Review 29(2): 163–201.

Heard, G. 2006. Pronatalism under Howard.People and Place 14(3): 12–24.

Henman, P., R. Percival, A. Harding and M. Gray. 2007. Costs of children: research commissioned by the Ministerial Taskforce on Child Support.Occasional Paper No. 18. Canberra: Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

Ho, C. 2006. Migration as feminization? Chinese women s experiences of work and family in Australia.Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 32(3):497–514.

Hugo, G.J. 2006. Immigration responses to global change in Asia: a review.Geographical Research 44(2): 155–172.

Kiernan, K.E. and A.J. Cherlin. 1999. Parental divorce and partnership dissolution in adulthood: evidence from a British cohort study.Population Studies 53(1): 39–48.

Kippen, R. 2004. Declines in first and second birth rates and their effects on levels of fertility.People and Place 12(1): 28–37.

Kippen, R. 2006. The rise of the older mother.People and Place 14(3): 1–11.

Lesthaeghe, R. 1995. The Second Demographic Transition in Western countries: an interpretation. Pp. 17–62 in K.O. Mason and A. Jensen (eds),Gender and Family Change in Industrialized Countries. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Liefbroer, A.C. and E. Dourleijn. 2006. Unmarried cohabitation and union stability.Demography 43(2): 203–221.

Marjoribanks, K. 2002.Family and School Capital: Towards a Context Theory of School Outcomes. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Marks, G.N. 2006. Family size, family type and student achievement: cross-national differences.Journal of Comparative Family Studies 37(1): 1–24.

McDonald, P. 1998. Contemporary fertility patterns in Australia: first data from the 1996 census.People and Place 6(1): 1–12.

McDonald, P. 2001. Family support policy in Australia: the need for a paradigm shift.People and Place 9(2): 14–20.

McDonald, P. 2002. Low fertility: unifying the theory and the demography. Paper presented to the 2002 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Atlanta, 9–11 May.

Merlo, R. and D. Rowland. 2000. The prevalence of childlessness in Australia.People and Place 8(2): 21–32.

Murphy, M. and L.B. Knudsen. 2002. The intergenerational transmission of fertility in contemporary Denmark: the effects of number of siblings (full and half), birth order, and whether male or female. Population Studies 56(3): 235–248.

Newman, L.A. and G.J. Hugo. 2006. Women s fertility, religion and education in a low-fertility population: evidence from South Australia.Journal of Population Research 23(1): 41–66.

Nie, Y. and R.J. Wyman. 2005. The one-child policy in Shanghai: acceptance and internalization.Population and Development Review 31(2): 313–338.

Parr, N. 2005. Family background, schooling and childlessness in Australia.Journal of Biosocial Science 37(2): 229–243.

Parr, N. 2006. Do children from small families do better?Journal of Population Research 24(1): 1–25.

Parr, N. and F. Guo. 2005. The occupational concentration and mobility of Asian immigrants in Australia.Asian and Pacific Migration Review 14(3): 351–380.

Parr, N. and M. Mok. 1995. Differences in the educational achievements, aspirations and values of birthplace groups in New South Wales.People and Place 3(2): 1–8.

Percival, R. and A. Harding. 2002. All they need is love and around $450,000. The AMP-NAT-SEM Income and Wealth Report Issue 3. Australia: AMP <http://www.amp.com.au/au/3column/0,2338,CH5306%255FSI56,00.html>. Accessed 25 January 2007.

Ross, J.A. 1992. Sterilization: past, present, future.Studies in Family Planning 23(3): 187–198.

Santow, G. 1991. Trends in contraception and sterilization in Australia.Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetries and Gynaecology 31(3): 201–208.

Short, S.E., L. Ma and W. Yu. 2000. Birth planning and sterilization in China.Population Studies 54(3): 279–291.

Sobotka, T. 2003. Re-emerging diversity: rapid fertility changes in Central and Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Communist regimes.Population (English Edition) 58(4–5): 451–486.

United Nations Population Division. 2006.World Population Policies 2005. New York.

Van de Kaa, D. 1997. Options and sequences: Europe s demographic patterns.Journal of the Australian Population Association 14(1): 1–30.

Watson, N. and M. Wooden 2002a. The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey: Wave 1 survey methodology.Hilda Project Technical Paper Series No 1/2. <http://www.melbourneinstitute.com/hilda/>.Accessed 1 May 2007.

Watson, N. and M. Wooden 2002b. Assessing the quality of the HILDA Survey Wave 1 Data.Hilda Project Technical Paper Series No. 4/02. <http://www.melbourneinstitute.com/hilda/>.Accessed 20 August 2007.

Weston, R. and L. Qu. 2001. Men s and women s reasons for not having children.Family Matters 58(Autumn): 10–15.

Weston, R., L. Qu, R. Parker and M. Alexander. 2004.It s Not for Lack of Wanting Kids … A Report on the Fertility Decision Making Project. Research Report No. 11. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parr, N. Which women stop at one child in Australia?. Journal of Population Research 24, 207–225 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03031931

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03031931