Abstract

The introductory chapter introduces the research project that the book’s chapters are built upon and identifies key questions that are addressed within the book’s thematic frame. The COST Action ‘ProSEPS’ project (Professionalization and Social Impact of European Political Science) collected updated information about the situation of the political science profession in Europe. Despite the widely acknowledged process of continental integration driven by the European Union (EU), the academic landscape has been and still is characterised by a great variety of traditions, institutions and resources. On this basis, this chapter explains that institutional development has been chosen as the major focus that could possibly introduce as well as explain the sources of this variety. It identifies the empirical, theoretical and comparative issues at stake and introduces the cases covered in the book and its structure.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Institutional development

- Political science

- Comparative analysis

- Peripheral and latecomer

- Integration and variety

This volume aims to analyse the institutionalisation process undergone by political science in Europe in recent decades. It reflects a part of the research conducted within the framework of the COST Action ‘ProSEPS’ (Professionalization and Social Impact of European Political Science) that started in late 2016.Footnote 1 ‘A part’, indeed, since it is the result of the work of the first of four working groups (WGs) assigned thematic tasks within the context of the Action.Footnote 2 In this introduction, we briefly introduce the research project and then identify key questions we believe need addressing within our thematic frame. Finally, we offer a series of insights together with an overview of the different chapters comprising this volume.

1 ProSEPS and the Working Group on the State of Political Science in Europe

The main tasks of WG1Footnote 3 were (1) to contribute, in the early phase of the project, to the identification of political scientists across Europe—a tentative ‘census’ subsequently built on by national teams in 2017–2018; (2) to contribute to the general online survey jointly edited by WG3 and WG4, distributed among European political scientists in 2018–2019 and (3) to provide updated information about the situation of the profession on the continent, in particular by generating reports (mostly of a qualitative nature) based on a questionnaire distributed among the Action’s participants (2018–2019).

In regard to the first point, Action participants quickly realised just how challenging a comparative study of the state of the discipline in Europe was. Despite the widely acknowledged process of continental integration driven by the European Union (EU), the academic landscape has been, and still is, characterised by a great variety of traditions, institutions and resources—and not simply due to the fact that not all European states are EU member states. Understanding the category ‘political science’ means dealing with a discipline which has been variously labelled (political science or political sciences, political science or political studies and political science or ‘politology’) and which has variable relationships with a variety of subfields, each independent to a lesser or greater degree (international relations, public policy, public administration, political economy, political sociology, research methods and political theory are some of the best examples of such); these sub-fields are sometimes included as a branch of political science, while in other cases, they purport to be independent from it and intersect with other neighbouring disciplines. These relationships are no mere formality. While they are often based on a functional rationale and are the result of organisational considerations, they can significantly impact political science in terms of teaching, research focus and methodology. Moreover, the potentially, and necessarily, evolving interconnections between them hint at the overall formation/transformation of political science per se. Under these circumstances, the mere definition of what a political scientist is proves to be much more challenging than it might seem at first sight. The enduring national peculiarities lead us to underline the continued relevance of the fundamental questions posed by Klingemann (‘How many political scientists are there in Europe? How many institutions are there to employ them? There is no easy answer to these questions’) (Klingemann, 2008, p. 375) and his consequent conclusion (‘political science is unable to provide quantitative data about even basic indicators such as students or academic staff’) (Klingemann, 2008, p. 392). While during our research we did our best to find reliable information, these difficulties are encountered even before we get to the comparative European level: in a number of countries, such information is not readily available.

While a great deal of information has been gathered over the course of our project, a number of limitations and difficulties have had to be dealt with. First of all, a COST Action, while representing a valuable tool for networking and cooperation, does not directly fund research. Our study of the discipline has been conducted with no such financial support, and this has severely limited our efforts. Moreover, it also deals with a field that has been explored by a very limited number of scholars. Therefore, it is difficult to identify scholars within each European country who possess experience of research into the discipline: political science is certainly what they practice but is not what they study. There is also a degree of divergence among the national political science associations operating in Europe: they differ considerably not only in terms of their activities (in certain rare cases, they are not active at all, and in other cases, they do very little) but also in terms of their production of regular information about the (national) profession.

Therefore, the ProSEPS scholars basically had to start from scratch and establish criteria with which to identify political scientists in Europe. This was not an easy task, but after much discussion, it was agreed that political scientists were to be identified on the basis of national legal criteria, insofar as such are available (e.g. national accreditation schemes and ministerial definitions/regulations), or if official/legal criteria do not exist, then on the basis of the combination of the following: (1) institutional affiliation (e.g. member of a department of political science), (2) possession of a PhD in political science and (3) research experience or having taught courses in political science. These groups are not necessarily exclusionary. But the point is clear: academic qualifications, professional experience and working environment together provide the basis for the establishment of the group of political scientists.Footnote 4 These criteria establish transparent selection markers which may sound excessively broad; however, an overly narrow definition of ‘political scientist’ would have led to the exclusion of actual political scientists who are not affiliated to a political science department. Bearing in mind that the population of political scientists was not defined for its own sake but was the basis for a survey, a more inclusive approach was preferred here.

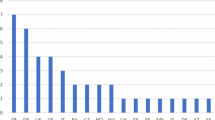

National delegates were then tasked with identifying political scientists in their own countries. While in some fortunate cases this information can be quickly and easily found, in others the task proved to be more complicated (sometimes very much more complicated). The lack of any clear-cut disciplinary boundaries in the institutional organisation of academic departments, the existence of private actors with no obligation to divulge their practices and the lack of transparency, or poor quality, of online resources were among the obstacles to what may have seemed a simple undertaking at first sight. At the individual level, asking political scientists questions about their affiliation or status could raise privacy issues. After careful examination, a tentative first census of European political scientists was developed by the network in 2017–2018. This census, based on an integrative perspective (meaning that litigious cases tended to be included rather than excluded), resulted in an estimated figure of just over 11,000 political scientists. Two countries (the UK and Germany) account for almost half of the population (more than 2100 and just over 2000, respectively), and the number of political scientists is around 1000 in both Russia and Turkey (Capano & Verzichelli, 2019, pp. 6–7). However, the data it relies on should be treated with caution due to the aforementioned difficulties, especially when being used for comparative purposes.

The data used also relied on the ProSEPS online survey, which was mainly conceived and conducted by WG3 and WG4 between March 2018 and January 2019 (see Real Dato & Verzichelli, 2019, Brans et al., 2019), although it benefited from the efforts of all Action members, including WG1 and WG2 (see Engeli & Kostova, 2019). Accordingly, the 52-question survey dealt with political scientists’ media visibility (written press, radio and television networks and online news) and their political consultancy/policy advisory services. Some questions addressed the ideas that political scientists themselves have of their own role in public debate and related activities, while others tried to assess the self-declared importance of internationalisation (in terms of publications, conference attendance, funding and linguistic practices); others still aimed at grasping the main subfields that political scientists taught. However, the resulting data were difficult to interpret since less than 21% of interviewees completed the questionnaire.

Finally, a third source is offered by the answers to a questionnaire tentatively dealing with ‘the state of political science in Europe’ (labelled in a purposely loose manner). The questionnaire was discussed by WG1 members and benefited from output from WG2 in its section on internationalisation. It was circulated among national experts from late 2018 onwards, when it was submitted, in its final version, to a meeting held in Sarajevo. Answers, taking the form of a series of national reports, were gradually received up until early 2019 (Ilonszki & Roux, 2019). Thematic sections addressed a number of different issues: the structuring of the political science community, the structure of political science education programmes, the features of political science research, the visibility of, and prospects for, the discipline and its internationalisation.

The gradual ‘awakening’ of the discipline was confirmed: whilst early attention was often devoted to political issues in some countries, through traditional institutions (chairs, academies and the like), the rise of political science as a discipline took place at various different moments during the course of the twentieth century, and in particular in the latter half thereof in conjunction with the emergence of mass higher education and advanced social science research in most Western countries, and at a later point—after the fall of authoritarian rule—elsewhere (i.e. in most of Southern and Eastern Europe). In addition to the differences in the pace of political science’s emergence, Europe also displays a considerable diversity of situations in terms of the different dimensions (education, research, institutions and resources) we need to explore in order to understand the current situation and its underlying dynamics. Once again, the considerable difficulty experienced in accessing information and establishing a valid comparison was evident. Although our group of scholars began producing preliminary data on this topic (Ilonszki & Roux, 2019), such data must be considered as a raw material requiring careful interpretation.

These questions were extensively discussed by the members of WG1 representing Austria, Belarus, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Hungary, Iceland, Lithuania, Malta, Moldova, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Serbia and Spain. As the list of countries suggests,Footnote 5 most of the countries represented were latecomers or enjoyed peripheral status within the profession, despite the fact that many have impressive record in terms of academic achievement in the field. Consequently, the considerable interest of the country representatives in the focus of WG1’s specific theme, namely the institutionalisation of the profession, was clear. WG1 was called upon to propose a joint undertaking regarding some of the trickiest questions concerning institutional development that in one way or another were important to all of us. This common interest matured into the idea of the present volume. While in the end not all the countries are represented in this volume, research is ongoing with those countries as well. Special thanks should go to our colleagues from the countries that have not provided authors for this book, as their input has nevertheless provided invaluable for the development of the project.Footnote 6

This is precisely how work started on this book. We chose to reframe the generic query into a more thorough research question concerning the institutionalisation of political science as an academic discipline: this required responding to a threefold challenge—empirical, theoretical and comparative—by embracing a cross-national undertaking based on a specific theoretical framework.

2 Understanding the Institutionalisation of Political Science in Europe’s ‘Periphery’

The following pages provide some insight into the difficulties academia faces, and the approaches and solutions it offers, when it analyses the institutionalisation of political science as an academic discipline in Europe in recent years.

The term ‘institutionalisation’ is commonly used but rarely defined. As DiMaggio and Powell (1991, p. 1) observe, ‘scholars who have written about institutions have often been rather casual about defining them; institutionalism has disparate meanings in different disciplines; and even within organization theory, “institutionalists” vary in their relative emphasis on micro and macro features, in their weightings of cognitive and normative aspects of institutions, and in the importance they attribute to interests and relational networks in the creation and diffusion of institutions”. In our search for a preliminary definition, we can start with Lanzalaco’s view that an ‘institution’ is the result of an ‘institutionalisation’ process, that is when social relations and behavioural models “a) are differentiated from other behavioural models and types of social relations…, b) acquire an intrinsic value… [and] c) are depersonalised” (Lanzalaco, 1995, p. 65).Footnote 7 While differentiation and depersonalisation can be seen as properties of the institutionalisation process, we believe that the acquisition of intrinsic value is more an outcome of the process than a definitional component of such. The concept effectively embraces the process by which political science became a separate discipline within European academia, with its own name, its durability and its own procedures for establishing the standards of scientific recognition, knowledge transmission and personnel training, hiring and promotion. Moving on from this general definition to how it can be applied to political science, we believe it requires complex considerations that exceed the scope of this introduction: consequently, these are developed separately in Chap. 2 (Ilonszki, this volume).

This simple conceptual underpinning has the advantage that it helps us organise our research. Of course, this is not the first time the discipline has been studied. Indeed, in Europe, its study gradually accompanied the global development of the discipline at the end of the twentieth century, and political science has been the object of a series of cross-national ‘pan-European’ overviews over the last two or three decades. Taking into account also the most recent studies made since the beginning of this century, some of these analyses have been made (mainly on the basis of an informative country-by-country approach) from a continental perspective (Boncourt et al., 2020; Klingemann, 2008; Krauz-Moser et al., 2015), while others have focused on Western Europe (Klingemann, 2007) or Eastern Europe (Eisfield & Pal, 2010; Kaase et al., 2002; Klingemann et al., 2002). To a certain degree, these volumes, together with all the articles published in this regard in academic journals, are themselves a sign that a process of discipline building has been successfully completed in recent decades. This comes as no surprise if we consider certain emblematic national cases such as that of the USA, the tentacular aspects and global influence of that nation’s political science community. Furthermore, the study of American political science can depend upon consolidated scholarship and benefits from the contribution of a powerful association and from the clear commitment of political scientists to monitoring their own discipline. Nevertheless, we should keep in mind that while the discipline’s reflection on its own being is not new to the American political science community, more recently it has also become a form of self-defense: when in 2009 a US senator proposed cutting funding to political science, claiming it to be a worthless (“good for nothing”) field, this was a wake-up call to political scientists who were called on to reflect on the discipline’s new tasks in a changing world. This is probably something that European political science should also think about: mere academic performance is not enough to make political science an acknowledged, institutionalised discipline. At the same time, it should be said that European political science is much more diversified than its US equivalent. In Europe, national political science associations appear less well-organised, and this lack of self-focus is indicative of the discipline’s degree of institutionalisation. Notwithstanding the substantial differences between the political science strongholds of North-Western Europe and other those of other parts of Europe, it was highly indicative that when asked if political science was acknowledged and recognised discipline in their country, almost all respondents, from Iceland to Bulgaria and from Portugal to Lithuania, ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that this was so.Footnote 8 How can such an agreement be accounted for, despite the evident differences in the strength of the discipline among such countries?

These challenges and difficulties explain why we chose the middle ground between updating the customary country-by-country report (‘what about political science in your country in 2020’) and a prospective European overview that would prove rather difficult and demand resources we do not have. In studying political science’s institutionalisation, our territorial focus here is clearly on Europe, although the cases selected for this volume do not cover the entire continent, indeed far from it. This is not only because the resources available to us did not allow us to do so. In addition to our WG membership, and to the partners concerned, the reflections shared with the other members of the working group led us to a growing conviction: rather than exploring the more obvious European success stories, we should turn our attention to the more peripheral cases and examine the difficulties political science actually faced in such countries. A valid concern raised some time ago but still an issue today is the question of whether these countries would simply ‘commute’ from one periphery to the other (Fink-Hafner, 2002) or manage to establish their own place in European political science.

We use ‘peripheral’ in a Rokkanian sense (Rokkan, 1999) to refer to those territories which appear to be severely deprived of a variety of resources that tend to be concentrated in core areas. Indeed, a striking feature of the development of political science in Europe has been its uneven nature, with it being most successful, as previously mentioned, in North-Western EuropeFootnote 9 (the United Kingdom, Germany, Scandinavia and the Netherlands), the centre for the various political science associations’ initiatives on the continent. If we are to understand the obstacles that the institutionalisation of political science has had to overcome and that it continues to face, we believe that we are more likely to gain insights into this question by looking to the margins rather than the core.

As a consequence, this book deals with a number of national cases that in the main encompass Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) together with Iceland and Malta—two small (in terms of population), insular, quite recently independent European countries located at the fringes (northern and southern, respectively) of Western Europe. It means that most of our cases were latecomers emerging from the post-Communist democratisation process in the 1990s, where the development of political science was delayed accordingly. This shows that political science has a ‘symbiotic relationship with democracy’ (Keohane, 2009, p. 363). Most of our attention is then devoted to the most recent decades, culminating in a portrayal of the profession as it stands in or around the year 2020.

This time period is very special, as for most of the countries covered here (the CEE countries) these were decades of significant transformation after the fall of the Berlin wall. This specific historical event can be seen as the point of departure for an institutionalisation process which, as one may have expected perhaps, should have involved several successive sequences of ‘innovation, diffusion and legitimation’ (Lawrence et al., 2001, p. 626), whereby the discipline would have been ‘created’, spread and anchored in the higher education and research landscape. However, as we now know, several important factors intervened in the meantime. CEE as a whole underwent a process of political change comprising (1) the creation of several new independent states (sometimes in violent conflict as in the case of the break-up of Yugoslavia); (2) democratic transition, in the case of both old and new states, which was affected by a significant political heritage and, in the long run, the persistence of authoritarian trends and (3) dealing with the influence of external factors such as globalisation, the effects of Europeanisation for EU member states (especially following the advent of the Bologna process) and the international weight of traditional actors such as Russia. At the economic level, a period of economic growth was accompanied by a modification of structures (the development of a market economy and the rise of the private sector) which have been mostly further affected, over the last decade, by the effects of the so-called Great Recession that hit Europe in the 2010s, not to mention the consequences of the more recent Covid-19 crisis which could not be included in our analysis. In other words, the context within which European political science has evolved, which has only been very briefly sketched here for reasons of space, has proven to be unstable and potentially highly problematic for the development of the discipline.

The chapters comprising this volume look at how Europe’s political scientists have addressed these various political and economic challenges. In our network’s underlying spirit of cooperation, we have added further features to this endeavour: we have chosen to avoid the common country-by-country structure of other analyses and have encouraged the contribution of comparative chapters on thematic issues. As Gelman says, ‘most political scientists still believe that Europe as a political entity is more than just a conglomerate of various countries, and the same statement is relevant for political science in this part of the world’ (Gel’man, 2016, p. 568). Indeed, this is the underlying approach we have adopted here, despite apparent country variations, when addressing the task of identifying the similarities and differences, developmental patterns and trends, sources of constraints and opportunities that characterise our profession. Nevertheless, we are well aware of the limitations to this undertaking, most notably the more nuanced presentation of their performance, that is, the contribution of these countries to the field. At the same time, it can be rightly argued that first we have to explore how the fundamental analytical components of stability, identity, legitimacy, autonomy and reproduction have been achieved in the process of institutionalisation of political science in the latecomer and peripheral countries dealt with here. On that basis, future research can examine whether the appraisal of their performance—that is, their general focus on the management of existing systems of government, insofar as they are self (nation)-centred and institution-oriented, while critical theories are almost absent (Eisfeld & Pal, 2010, p. 15)—is still valid or whether a more nuanced and more varied picture evolves over time.

Indeed, politics and political science change quickly, as shown by the different rankings of our cases and by our grouping of the countries, compared to how they were grouped in Eisfeld and Pal’s volume (2010 introduction). The Balkan States (Bulgaria and Romania) and the Visegrád countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) are now grouped together in Chap. 5, as they now seem to be facing similar challenges in the process of institutionalisation. The post-Yugoslavia chapter (Chap. 4) includes more cases now due to the understanding that the relevance of political science has broadly increased. The post-soviet republics are now placed together with two Baltic states (post-Soviet republics themselves) in Chap. 3 in order to examine and explain the different trajectories concerned.

Altogether, in addition to the introductory and conclusive chapters (Chaps. 1, 2 and 9), this volume contains six thematic chapters where the authors aim to establish the fundamental aspects of political science’s institutionalisation on the basis of country comparisons. These chapters, in addition to the specific knowledge of the country experts involved, also build on the methodological input of the COST project as mentioned above, comprising the questionnaire, the survey and the political science database.

Table 1.1 (appendix of this chapter) offers an illustration of this endeavour. It consists of a list of 30 of contextual features for the development of political science in the 16 countries under scrutiny in the book. It provides some basic information about the discipline and it adds important contextual factors demonstrating the academic environment in which political science operates. One can observe two substantial features—one is diversity between the countries and the other the challenges that virtually each country must face. As to the former particularly in terms of long-term demographic and financial perspectives, the country differences are huge. For example, Belarus and Serbia are clearly under threat, and with the exception of Croatia and Iceland, university student and staff numbers tend to decline. While funding, international connectedness, and academic performance indicators again show country differences in most countries, they are the expressions of constraints. These shortcomings and even failing patterns will provide the background of the institutionalisation of political science in the comparative chapters of the book.

3 Plan of the Book

The book is organised as follows. Chapter 2 by Gabriella Ilonszki offers a theoretical framework with which to address the issue of institutionalisation. Rather than using the work in a loose metaphoric manner, she has anchored our reflections on the discipline to the broader debate so that our work may benefit from those insights provided by the various institutionalist traditions. This allows us to build a basis for the empirical elements that the other chapters are based upon. In Chap. 3, Tatsiana Chulitskaya Dangis Gudelis, Irmina Matonyte and Serghei Sprincean shed light on the transformation of the profession in post-Soviet Belarus, Estonia, Lithuania and Moldova. This is perhaps the chapter that most clearly shows how context influences institutionalisation opportunities as well as the very existence of the discipline. Chapter 4, written by Davor Boban and Ivan Stanojević, focuses on the case of former Yugoslavia: how the different parts of a once-united country, that subsequently gave rise to separate nation states, has managed the development of political science? Have shared traditions led to lasting similarities? Or have the separate paths followed by each new state produced significant differences? The authors claim that Yugoslavia, where early institutional innovation was more important than in other parts of Communist Europe, has resulted in the second scenario for the following reasons, which they carefully analyse here: a lack of financial resources, the influence of Europeanisation, the existence of authoritarian trends and the importance of private institutions in some areas, all of which have combined to produce a fragmented landscape whose further development is rather unpredictable. As a partial rejoinder, in Chap. 5, Aneta Világi, Darina Malová and Dobrinka Kostova assess the situation of political science in six countries where it appears to be under attack as such. They show that after an initial phase of development, the situation slowly worsened and political scientists, along with other academics, were attacked for who they are—or rather for what they are depicted as being and doing. In Chap. 6, Eva Marín Hlynsdóttir and Irmina Matonyte analyse the institutionalisation process in ‘small states’ (Estonia, Malta, Iceland and Slovenia). The underlying observation they make is that the lack of resources, often indicated as a key factor limiting the development of the discipline, is not always just a matter of geographical location. Size, mostly in terms of population, is an interesting issue. In Chap. 7, Gabriella Ilonszki, Davor Boban and Dangis Gudelis look at the question of relevance by comparing Hungary, Croatia and Lithuania. They show that changing legitimacy is a major factor in how the profession becomes relevant. In Chap. 8, Erkki Berndston tackles the issue of internationalisation. This chapter demonstrates that although there are currently several active European political science associations—the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR), the European Political Science Association (EPSA) and the European Confederation of Political Science Associations (ECPSA)—the latecomer political science communities have a limited presence of. The book’s concluding chapter (Chap. 9 by Christophe Roux) looks at the general trends that emerge from the work of the book’s authors and underlines the importance of the challenges ahead.

Notes

- 1.

COST Action CA15207 (Professionalization and Social Impact of European Political Science) (2016–2021). It originally comprised a total of 103 people from 42 countries, including those with a Eurasian basis (such as Russia and Turkey), and took into account non-European observers (USA, Canada). See https://www.cost.eu/actions/CA15207/ (retrieved on September 11th, 2020).

- 2.

WG1 dealt with the state of political science, WG2 with internationalization, WG3 with media visibility and WG4 with the policy impact of political scientists. Decisions regarding the Action as a whole were managed by its Core Group and its General Assembly.

- 3.

The group (chaired by Gabriella Ilonszki and vice-chaired by Christophe Roux) has held seven meetings, either alone or with the other working groups across Europe. Its last meeting, due to be held in Valencia, Spain, in March 2020, had to be cancelled due to the COVID-19 crisis.

- 4.

A broad approach was suggested, that is to consider membership in departments/institutes of political science, political studies, international relations, public administration, public policy, political theory (and also, eventually, departments / faculties / schools or institutes of neighboring institutions like European studies, law, area studies, geography, economy, sociology, psychology, management, communication, history, environmental and health sciences and so on).

- 5.

We only regret that we were not able to systematically include representatives from large academic communities (Germany and the United Kingdom first and foremost, but also countries such as Poland, the Netherlands and the Scandinavian countries).

- 6.

We would like to thank Miguel Jerez and Marcelo Camerlo their contributions in regard to Spain and Portugal, respectively.

- 7.

We would like to thank Giliberto Capano for having drawn our attention to this reference.

- 8.

ProSEPS WG1 National Reports. Only Malta is the exception to the rule.

- 9.

References

Boncourt, T. (2015). A Discipline on the Edge. An Overview of the History and Current State of Political Science in France. In B. Krauz-Morer, M. Kułakowska, P. Borowiec, & P. Ścigaj (Eds.), Political Science in Europe at the Beginning of the 21st Century (pp. 109–131). Jagiellonian University Press.

Boncourt, T., Engeli, I., & Garzia, D. (Eds.). (2020). Political Science in Europe. Achievements, Challenges, Prospects. Rowman & Littlefield International.

Brans, M., Timmermans, A., & Gouglas, A. (2019). The Advisory Role of Political Scientists in Europe. ProSEPS Report by Working Group, 4. Retrieved September 22, 2020, from http://proseps.unibo.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/WG4.pdf

Capano, G., & Verzichelli, L. (2010). Good but not Enough: Recent Developments of Political Science in Italy. European Political Science, 9(1), 102–117.

Capano, G., & Verzichelli, L. (2019). Introduction: Goals and Methodology. ProSEPS Introductory Report. Retrieved September 22, 2020, from http://proseps.unibo.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/introduction.pdf

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). ‘Introduction’. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis (pp. 1–39). The University of Chicago Press.

Eisfeld, R., & Pal, L. (Eds.). (2010). Political Science in Central-Eastern Europe. Diversity and Convergence. Barbara Budrich.

Engeli, I., & Kostova, D. (2019). Towards a European Political Science? Opportunities and Pitfalls in the Internationalisation of Political Science in Europe. ProSEPS Report by Working Group, 2. Retrieved September 22, 2020, from http://proseps.unibo.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/WG2.pdf

Gel’man, V. (2016). European Political Science at the Beginning of the 21st Century. Book Review. European Political Science, 15, 567–570. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-016-0069-4

Fink-Hafner, D. (2002). Political Science – Slovenia. In M. Kaase & V. Sparschuh (Eds.), Three Social Science Disciplines in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 358–374). GESIS/Collegium Budapest.

Ilonszki, G., & Roux, C. (2019). The State of Political Science in Europe. ProSEPS Report by Working Group, 1. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from http://proseps.unibo.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Working-Group-1-Report-The-State-of-Political-Science.pdf

Kaase, M., Sparschuh, V., & Wenninger, A. (2002). Three Social Science Disciplines in Central and Eastern Europe. Handbook on Economics, Political Science and Sociology (1989–2001). Berlin-Budapest, Social Science Information Centre (IZ) – Collegium Budapest.

Keohane, R. (2009). Political Science as Vocation. Political Science and Politics, 42(2), 359–363.

Klingemann, H. (Ed.). (2007). The State of Political Science in Western Europe. Barbara Budrich.

Klingemann, H. (2008). Capacities: Political Science in Europe. West European Politics, 31(1–2), 370–396.

Klingemann, H., Kulesza, E., & Legutke, A. (Eds.). (2002). The State of Political Science in Central and Eastern Europe. Sigma.

Krauz-Moser, B., Kułakowska, M., & Borowiec & Ścigaj P. (Eds.). (2015). Political Science in Europe at the Beginning of the 21st Century. Jagiellonian University Press.

Lanzalaco, L. (1995). Istituzioni, organizzazioni, potere. Introduzione all’analisi istituzionale della politica [Institutions, Organizations, Power. Introduction to Institutional Political Analysis]. La Nuova Italia Scientifica.

Lawrence, T. B., Winn, M. I., & Jennings, P. D. (2001). The Temporal Dynamics of Institutionalization. The Academy of Management Review, 26(4), 624–644.

Marino, L., & Verzichelli, L. (2020). Political Science in Italian Universities: Demand, Supply and Vitality. Italian Political Science, 14(3), 217–228.

Real Dato, J., & Verzichelli, L. (2019). Social Visibility and Impact of European Political Scientists. ProSEPS Report by Working Group, 3. Retrieved September 22, 2020, from http://proseps.unibo.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/WG3.pdf

Rokkan, S. (1999). State Formation, Nation-Building and Mass Politics. Oxford University Press.

Smith, A. (2020). A Glass Half-Full: The Growing Strength of French Political Science. European Political Science, 19(2), 253–271.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ilonszki, G., Roux, C. (2022). Introduction: The Then and Now of Political Science Institutionalisation in Europe—A Research Agenda and Its Endeavour. In: Ilonszki, G., Roux, C. (eds) Opportunities and Challenges for New and Peripheral Political Science Communities. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79054-7_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79054-7_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-79053-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-79054-7

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)