Abstract

Few patients are as helpless and totally dependent on nursing as long-term intensive care (ICU) patients. How the ICU nurse relates to the patient is crucial, both concerning the patients’ mental and physical health and well-being. Even if nurses provide evidence-based care in the form of minimum sedation, early mobilization, and attempts at spontaneous breathing during weaning, the patient may not have the strength, courage, and willpower to comply. Interestingly, several elements of human connectedness have shown a positive influence on patient outcomes. Thus, a shift from technical nursing toward an increased focus on patient understanding and greater patient and family involvement in ICU treatment and care is suggested. Accordingly, a holistic view including the lived experiences of ICU care from the perspectives of patients, family members, and ICU nurses is required in ICU care as well as research.

Considerable research has been devoted to long-term ICU patients’ experiences from their ICU stays. However, less attention has been paid to salutogenic resources which are essential in supporting long-term ICU patients’ inner strength and existential will to keep on living. A theory of salutogenic ICU nursing is highly welcome. Therefore, this chapter draws on empirical data from three large qualitative studies in the development of a tentative theory of salutogenic ICU nursing care. From the perspective of former long-term ICU patients, their family members, and ICU nurses, this chapter provides insights into how salutogenic ICU nursing care can support and facilitate ICU patients’ existential will to keep on living, and thus promoting their health, survival, and well-being. In a salutogenic perspective on health, the ICU patient pathway along the ease/dis-ease continuum reveals three stages; (1) The breaking point, (2) In between, and (3) Never in my mind to give up. The tentative theory of salutogenic long-term ICU nursing care includes five main concepts: (1) the long-term ICU patient pathway (along the salutogenic health continuum), (2) the patient’s inner strength and willpower, (3) salutogenic ICU nursing care (4), family care, and (5) pull and push. The salutogenic concepts of inner strength, meaning, connectedness, hope, willpower, and coping are of vital importance and form the essence of salutogenic long-term ICU nursing care.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The main difference between patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) and other patients is that the former are severely critically ill and need advanced life-sustaining care, including mechanical ventilation. ICU patients need fundamentals of care such as keeping clean, warm, fed, hydrated, dressed, comfortable, mobile, and safe. ICU patients who need mechanical ventilation are unable to talk. They are therefore totally dependent on others, including having others interpret their symptoms and feelings. This means that advanced medical treatment and technology need to be accompanied by advanced nursing care. In this chapter, we argue for the relevance of a health promotion perspective in the care of acutely/critically ill patients. The aim of this chapter is to enhance understanding of the essence of long-term ICU care in a health promotion perspective. We build our analysis on qualitative data on former long-term ICU patients’ experiences of their struggle to survive, together with the experiences of ICU nurses and patients’ family members. This chapter is written from our home-offices since all universities are locked down due to the COVID-19 infection worldwide. The present Covid-19 pandemic demonstrates that a health promotion approach in the care of long-term ICU patients is ever more important in the years to come. The pathophysiology of severe viral pneumonia (as in COVID-19) is acute respiratory distress syndrome, which is associated with a prolonged ICU stay [1]. A retrospective study from the Lombardy region in Italy demonstrated that 5 weeks after the first admission to the ICU, most of the COVID-19 patients (58%) were still in the ICU showing a higher need for mechanical ventilation than other ICU patients [2]. ICU care of COVID-19 patients is challenged by isolating regimes with limited human contact. ICU nurses caring for the patients are wearing medical masks, gowns, gloves, and face shields, and visits from family members are banned [1]. From a health promotion perspective, these factors might cause stress for patients, family members, and nurses, and negatively affect the patients in the recovery process.

This chapter starts with an outline of research on long-term ICU patients. Following this, a specific nurse–patient situation with data from observations in an ICU (the story of Peter) is used to give the reader insight into the key aspects of care for the long-term ICU patient. The story runs like a thread throughout the chapter, leading the reader through the phases of ICU nursing with a focus on salutogenesis and health promotion. Our aim is to demonstrate how clinical skills are context-specific, and how these skills are manifested in a specific encounter with an individual patient. This chapter is placed in a health promotion perspective and is based in the salutogenic health theory. The chapter is divided into sections on theoretical perspectives, purpose, methodology, results, and discussion of the findings.

2 Background

Recent years have seen an increasing focus on the long-term consequences for ICU patients after hospital discharge. Former ICU patients may suffer from physical and mental health problems with a negative impact on quality of life and daily functioning [3]. The term post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) describes new or worsening problems in physical, cognitive, or mental health status arising after a critical illness and persisting beyond acute care hospitalization [4]. Possible mechanisms of PICS are insufficient supply of oxygen (hypoxia), treatment such as a tube is inserted into the patients’ airway (endotracheal intubation), frequent use of benzodiazepines, immobilization, and interruption of the sleep-wake cycle [4]. Health promoting and rehabilitation efforts should therefore already be initiated during the ICU stay [3].

A growing evidence suggest that the ABCDEF bundle (A, assess, prevent, and manage pain; B, both awakening and spontaneous breathing trials; C, choice of analgesic and sedation; D, delirium: assess, prevent, and manage; E, early mobility and exercise; and F, family engagement and empowerment) improves ICU patient-centered outcomes and promotes interprofessional teamwork and collaboration [5, 6]. A multicenter prospective cohort study among 15,226 adults concluded that ABCDEF bundle performance showed significant and clinically meaningful improvements in outcomes including survival, mechanical ventilation use, coma, delirium, restraint-free care, and ICU readmission [7]. It was suggested that the bundle components including several elements of human connectedness (waking patients, holding their hand and patients regaining a feeling of control over actions and their consequences) had a positive influence on patient outcomes. However, these nursing interventions cannot easily be quantified; a recent Scandinavian study suggests a shift from technical nursing toward an increased focus on patient understanding, and greater patient and family involvement in ICU treatment and care [8]. Therefore, future studies could benefit from a more holistic view, including the lived experiences of ICU care from the perspectives of patients, family members, and ICU nurses.

The suggestion that patients and their family members be involved in care was first introduced by the Picker Institute in 1988. Since then, family inclusion has evolved into a model of collaboration between and among patients, families, and health care providers [9]. The guidelines for family-centered care [10] highlight the importance of future research to improve collaboration with patient and family in ICU care [10].

Although considerable research has been devoted to long-term ICU patients’ experiences from their ICU stays [11], less attention has been paid to health promoting factors [12, 13] that encourage ICU patients’ existential will to keep on living [14]. Knowledge of health promotion in ICU care from the perspectives of ICU patients, their family members, and ICU nurses may improve the quality and efficiency of long-term ICU care. Therefore, we suggest the need to develop a tentative theory of salutogenic ICU nursing care to describe long-term ICU care and the health promotion process of getting through the illness trajectory.

3 Theoretical Foundation

The choice of theoretical perspectives, models, interventions, and reflections included in this chapter are based on their usefulness for ICU nursing and health care. Further, this chapter emphasizes ICU patients’ and their families’ perspectives on ICU health promotion. This chapter is based on our own empirical research [14,15,16,17,18], as well as our extensive clinical experience in ICU nursing and nursing of the chronically ill, including palliative patients. The literature we build on is grounded in both qualitative and quantitative research. In a health promoting perspective, we draw on the salutogenic theory of Antonovsky [19,20,21] and the philosophy of nursing care formulated by the Norwegian nurse and philosopher Kari Martinsen [22, 23]. Additionally, this presentation was substantiated with a literature search using the terms “intensive care patients,” “critical care patients,” “family,” “family member,” “next of kin,” “health promotion,” “salutogenesis,” and “long-term ICU care.” Since we live in Norway, and have studied and worked there, our examples from clinical practice are drawn from the Norwegian context.

3.1 Health Promotion in the Health Care

In 1986 the World Health Organization (WHO) arranged the first international conference on Health Promotion, resulting in the Ottawa Charter. This charter defined health promotion as “the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve their health,” and identified basic strategies for health promotion. An international network of health promotion hospitals (HPH) was later established, with an aim of reorienting the hospitals in a health promoting direction. However, in order to succeed in doing so, knowledge and evidence on health promoting nursing centering on patients’ health and resources were needed. Several theories of health promotion have been developed, among which the salutogenic health theory by Antonovsky [19, 24] is central. Available evidence guiding long-term ICU nursing care into a more health promoting direction is scarce. Hence, this chapter aims at developing a tentative theory of salutogenic ICU nursing care.

3.2 The Salutogenic Understanding of Health

Aron Antonovsky (1923–1994) challenged the conventional paradigm of pathogenesis and its dichotomous classification of persons as being either healthy or diseased [19]. He coined the concept of salutogenesis, which means the origin of health. Basically, salutogenesis—the salutogenic understanding of health and the gradually evolving salutogenic concepts—signifies knowledge about the origin of health, i.e. about what provides, facilitates, and supports health. The concept of salutogenesis has matured since 1986 and has become a core theory of health promotion [21]. From a salutogenic perspective, health is a positive concept involving social and personal resources, as well as physical capacities. Hence, the salutogenic theory of health offers a resource-oriented and strength-based perspective, i.e. a broad focus on the genesis or sources of health, as well as circumstances promoting or undermining health.

Figure 1.1 in Chap. 1 in this book illustrates how Antonovsky saw health as a movement along a continuum on a horizontal axis between health-ease (H+) and dis-ease (H−) [25]. Health promotion and salutogenic ICU nursing care intend to move the patient along this continuum toward the positive end, termed H+. According to Antonovsky, sense of coherence (SOC) is a vital health resource moving the individual toward good health. While facing stressors in life, such as, e.g., serious illness, tension appears. To avoid breakdown, and instead move along the continuum in the positive direction, the patient must cope with the tensions. A strong SOC as well as generalized resistance resources (GRRs) will help the seriously ill person to cope, to stand out with the suffering, to survive and recover. Looking at Fig. 18.1, GRRs are important to hinder breakdown and move the ICU patient along the ease/dis-ease continuum toward best possible health. The salutogenic approach to long-term ICU patients is resource-oriented and focuses on the patient’s ability to manage the stressors in this specific life situation to recover and stay healthy.

The SOC and the GRR represent key concepts of the salutogenic health theory. SOC is defined as “a global orientation that expresses the extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring through dynamic feeling of confidence that: (1) the stimuli from one’s internal and external environments in the course of living are structured, predictable and explicable; (2) the resources are available to one to meet the demands posed by these stimuli; and (3) these demands are challenges, worthy of investment and engagement” ([24], p. 19). SOC includes the three dimensions of comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness (ibid.). Comprehensibility represents the cognitive aspect of SOC, including the capacity to appraise one’s reality and to understand what is going on. A seriously ill ICU patient might struggle to grasp what is taking place around him. The second aspect, manageability covers an individual’s instrumental and behavioral capacity to manage and cope with the situation. Coping is difficult if you do not understand what is happening with you. Finally, the meaningfulness aspect involves an individual’s feelings that life makes sense emotionally, and that the present challenges are worth investing one’s effort and energy in; that is, one’s commitment and engagement. Meaningfulness is seen as the motivation aspect of SOC. Finding meaningfulness and thus motivation to fight for survival might be hard to the long-term ICU patient who is at “a breaking point” (Figs. 18.2 and 18.3). These three aspects of SOC—comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness—are involved when an individual experiences a long-term ICU stay. As illustrated by the example of Peter down under, long-term ICU patients experience several and huge stressors, and thus much tension. The need for resistance resources is obvious. GRR represents a set of resources promoting meaningfulness, comprehensibility, and thus manageability (SOC). GRRs are present in an individual’s personal capacities, but also in the immediate and distant environment [24, 26]. A strong SOC enables one to recognize, pick up, and utilize the available GRRs. Salutogenic ICU nursing care supports the patient’s awareness and use of the resources available. The patient’s family and the ICU nurses should perform as GRR resources during the long-term ICU stay. Specifically, close family members can help to identify and facilitate personal GRRs for their ICU patient.

Furthermore, Antonovsky understood the relationship between the two orientations of pathogenesis and salutogenesis as complementary [20]. We therefore emphasize that health promotion approaches do not imply a disregard of pathogenesis. Knowledge of pathogenesis, i.e. knowledge of disease, risk, and prevention, is important in all health disciplines, and naturally in health care, particularly in the ICU context. When people become injured or seriously ill, whether it be an accident, heart disease, lung disease, cancer, mental illness or the need for a surgical intervention, knowledge of illnesses, injuries and trauma, and their treatment, is crucial to their lives. However, instead of juxtaposing pathogenesis and salutogenesis, it is pertinent to assimilate these two paradigms into a manifestly holistic way of understanding and working with health. Health is always present, while illness and injury occur from time to time. Thus, health is the basis and the origin, and should therefore be the foundation of health care, also in the ICU. We use Peter throughout this chapter to depict the movement along the health continuum during the long-term ICU patient’s pathway.

-

Background: Peter was in a road accident 2 days ago with complicated fractures of his back, femur and ankle. He also has serious rib fractures and bleeding in his chest cavity, requiring mechanical ventilation. Peter’s bed is by the window. Over his head hangs a monitor. Right next to the head of his bed, the ventilator produces a rhythmic sound. On the monitor a graph moves, looking like a row of mountain peaks. Suddenly a lung appears at the top of the screen, and then disappears again. We can also see numbers that keep changing. Peter moves his arms and head, and suddenly a sharp sound is heard and a light flashes on the ventilator. Then it goes quiet again just as quickly. Next to the bed are infusion pumps for medication. Several chains with a hook on the end hang from a rail in the ceiling. On one of them is a photo of a man and a little child. A photo that links Peter to a life outside this room.

-

Peter’s reflections on his stay in the ICU (comprehensibility, meaning, manageability):

-

I was more like a rocket that was shot up into the sky, there was lots of noise, lots of loud noises and steel, rockets are full of steel, aren’t they? Then when it was going up into the sky, bits of it began to fall off and then when it reached a certain level, it stopped, and it began to fall again. It was a terribly long and tiresome trip! And on the way down, the bits of metal came back on again and then it fell to the ground. And I think ... I think the connection is that the day after I arrived at the ICU, I was operated on. They put steel in my back, it was stiffened, and I heard that noise and everything that was going on, I think ... I’m quite sure about that!

-

The family member’s reflections:

-

There was no communication the days he was on the ventilator. So, then we just made short visits. I went in and looked at him and stroked his cheek and then I talked a bit to the nurses.

Peter is an entity of body-mind-soul who is at a breaking point: will he survive his huge injuries, or will he pass away? We do not know yet. In this early unstable phase, medical treatment is urgent. The patient needs stabilizing, organ support like mechanical ventilation and dialysis, and symptom treatment like pain relief and sedation. However, a health promotion approach also includes family members’ presence and nursing care, as well as awareness toward Peter’s sense of comprehensibility, manageability and meaning. How can the nurses help him to understand what is going on? How much information is he able to take? What can make him find meaningfulness, and a sense of manageability in the midst of ailments and fatigue?

While people face various life stressors, such as serious illness leading to a long-term stay in an ICU, research has shown that those who, despite the difficulties, experience meaning-in-life cope better and report more well-being than those who experience meaninglessness. Meaning is an important psychological variable that promotes well-being [27,28,29], protects individuals from negative outcomes [30, 31], and serves as a mediating variable in psychological health [32,33,34,35,36]. The concept of meaningfulness is also crucial in the salutogenic theory of health [19, 24] that focuses on health promoting resources, among which sense of coherence (SOC) is vital. Individuals with a strong SOC tend to perceive life as being manageable and believe that stressors are explicable; thus, they have confidence in their coping capacities [37]. Several studies link SOC with patient-reported and clinical outcomes such as perceived stress and coping [38], recovery from depression [37], physical and mental well-being [39, 40], and satisfying quality of life and reduced mortality [41, 42]. SOC has thus been recognized as a meaningful concept for patients with a wide variety of medical conditions.

3.3 Health Promoting Long-Term ICU Nursing

The theoretical perspective is based on a view of nursing as a practical discipline and on professor Kari Martinsen’s philosophy of nursing care. The caring situation in nursing is by nature concrete and contextual. Care has a relational, practical and moral dimension ([22], pp. 14–20). A central ontological feature of Martinsen’s theoretical work is the assumption that human beings are interconnected and dependent upon each other; humans are born as relational individuals. Thus, without a relationship with a “you,” there cannot be an “I.” The individual can only become a living person in a relationship with a “you” [23, 43, 44]. This dependence on others must not be seen as negating independence; however, people can never understand and realize themselves alone or independently of others. Care is fundamental and natural, but also difficult because in relationships with others we are vulnerable to the other’s gaze, mood, and body language. We may ignore or reject what the other is expressing. This implies that human relationships are ethical. Care is to relate to the other and to be able to recognize and respond to the patient’s needs [44]. The specific encounter with the long-term ICU patient thus has a moral dimension. As nurses, we can look, and overlook.

A recent Danish study argued for the development of theory in clinical nursing to meet the needs of patients and relatives [45]. Consequently, in the present study we explore and illuminate central concepts in health promoting family-centered long-term ICU care. The focus is not on giving the actual concepts fixed meanings, but on creating a useful understanding of the shared meaning of concepts within a specific context [46]. A conceptual framework aims at prescribing broad, open-textured (structured) assumptions of how phenomena in a field are to be understood [47]. Within the framework of health promotion, we aim to articulate the values and goals of nursing by making aspects of this practice explicit and analyzing patients’ needs [48].

4 Purpose

The purpose of this study was to gain a deeper understanding of the essence of long-term ICU care in a health promotion perspective. A more specific aim was to identify central salutogenic concepts in long-term ICU patients’ lifeworld. From the perspective of former long-term ICU patients, their family members, and ICU nurses, this study provides insights into how salutogenic resources can be used to support and facilitate ICU patients’ existential will to keep on living. Finally, we aim to propose a tentative theory of salutogenic long-term ICU nursing care.

5 Design and Methods

A hermeneutic phenomenological approach was applied, illuminating the meaning embraced in people’s experiences and forms of expression [49, 50].

5.1 Settings and Sample

This study was based on three different qualitative datasets about long-term ICU patients’ struggle to survive, as experienced by (1) the patients themselves, (2) their family members, and (3) ICU nurses. Data were collected from two university hospitals and two local hospitals in Norway between 2004 and 2017.

5.2 Data Collection

The three datasets included (1) six in-depth interviews of experienced ICU nurses before and after observations of nurse–patient interactions in mechanical ventilation, collected in 2004, (2) interviews of ICU patients 5–14 months after ICU discharge (collected in 2012–2014), and (3) interviews of ICU patients, family members, and ICU nurses involved in long-term ICU care (collected in 2016–2017) (Table 18.1). A total of 28 long-term ICU patients, 13 family members, and 13 ICU nurses participated in the study. Further details are published elsewhere [14, 16,17,18].

5.3 Data Analysis

The datasets were handled as a whole and analyzed by the following steps: First, the authors presented and reflected on the results from the first analysis of all datasets using themes and subthemes. Second, a reflective discussion was guided by the following questions: What are the characteristics of long-term ICU patients? What is the essence of long-term ICU care and the health promotion process of getting through the illness trajectory? Third, the original empirical data were reread to identify real life examples of the health promotion process and were further interpreted as phases. Fourth, the reading of literature in the fields of lifeworld research and health promotion concepts based on salutogenic theory [20, 21] inspired further interpretation of data. Fifth, essential concepts describing the health promotion process of getting through the illness trajectory in long-term ICU care and suggested relationships among these concepts were developed [51]. The concepts were framed within the salutogenic theory and the ABCDEF bundle approach [6].

5.4 Characteristics of the Researchers

Two authors (IA, HSH) are ICU nurses, with expertise in teaching, clinical practice, and research, while the third author (GH) is a specialist in the nursing care of chronically ill patients and end-of-life care and has published widely in health promotion research among different populations.

5.5 Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was not sought, as the study is based on a secondary analysis of data from published studies.

6 Results

The health promotion process of getting through the illness trajectory during the ICU stay was interpreted as three overlapping phases: (1) A body at a breaking point, (2) In between, and (3) Never in my mind to give up (Table 18.2). This process is not linear, but depends upon the severity of the disease, the patient’s progress and setbacks, courage and despondency, hope and despair. Inner strength [52], perceived meaning-in-life [53, 54] as well as meaningfulness [19], connectedness [55], hope [56, 57], willpower [58], and coping [59] appeared to be vital salutogenic resources for long-term ICU patients, particularly in phases 2 and 3, after the first critical phase (“A body at a breaking point”). Knowing the patient was important to both family members and ICU nurses. The concepts of pull and push used by the nurses were found to be important in all three phases and seemed to be associated with the other health promotion resources identified.

6.1 A Body at a Breaking Point

-

Observation during morning care:

-

The nurse speaks directly to Peter: “Please bend your foot when we turn you over.” He can’t do that. He’s completely limp when we raise his arms and wash him. The nurse suctions the endotracheal tube before we turn the patient to prevent him coughing badly when he lies on his side during care and changing the sheets. Following the care, Peter is placed up in bed, supported with four pillows. The curtains are pulled aside to let in the light. They put a blanket over him and air the room. The nurse takes a blood gas. When she returns, he’s coughing up white foamy phlegm. His face is red and sweaty, and his respiratory rate is 30 breaths per minute. We move him more over on his side as we can smell stool. Then we close the door, pull down the curtains and change his diaper. When he’s put back on his back, his face is still red and sweaty, his breathing is rather superficial, and his blood pressure is rising.

-

Peter’s reflections (comprehensibility, meaning, manageability):

-

The moment when I crashed, I lost consciousness. Before I woke up, three people who have been very close to me came to see me on a mountain. We were lifted together in four pillars of light into heaven—they explained to me that this life was over, and I had to choose where to live my next life! But suddenly I was in the ICU, looking down at myself for a moment, and suddenly I was inside myself again!—An extraordinary experience!

-

The nurse’s reflections:

-

Although we had no contact with him yesterday, he was lying there with his eyes open and looking around. And then I use the care situation to assess him more closely. Mainly, I look at the patient, and form a mental picture of how well he is based on how he looks and feels. That’s the main thing I do. Then I look at what he’s getting from the ventilator, look at the monitor values and then I sometimes also take a blood gas to have some figures to lean on.

-

In principle, it’s important for the patient to have rest periods, and it’s especially important at night. There shouldn’t be bright light and activity around the patient all the time. You have to find a balance, but it depends on how much there is to do around the patient. How long the care takes, if you have to change e.g. the central venous catheter, arterial catheter and the wounds. How much rest we can achieve depends on the particular situation and the individual patient. And it depends a bit on us too, how much we allow a patient to rest.

The situation reveals a sensory presence in which the nurse uses all her senses (looking, listening, touching, smelling) to assess and understand the patient’s condition: “Yesterday, his eyes were open and he was looking around” is interpreted as a sign of health which the nurse sees as a resource to build on. The nurse’s presence, attention and care are health promoting resources, supporting and facilitating the health-giving processes taking place in the patient as an entity of body-mind-spirit. The body is at a breaking point. Thus, the mind and spirit are also in a state that may be termed a “breaking point.” In a health promotion perspective, the ICU nurse is aware of every sign of health (his eyes are open, looking around) on which she can build her presence, attention and care. Hence, if we adapt Fig. 1.1 in Chap. 1 to Peter’s situation, it may be portrayed as in Fig. 18.1.

Figure 18.1 shows the health ease/dis-ease continuum: a huge stressor appears, and Peter’s body is suddenly at a breaking point in the ICU. Peter’s situation is characterized by unconsciousness, sedation, exhaustion, weakness, and discomfort, which are experiences also described in other studies as tiring delusions, feeling trapped, and being on an edge between life and death [60,61,62]. At this point, both pathogenesis and salutogenesis are vital perspectives and approaches in the ICU. Peter may move along the health continuum: either toward breakdown or in the positive direction. Along with medical treatment, the intensive nursing care involves facilitating the salutogenic resources embedded in Peter’s situation and the context. By actively supporting and strengthening the salutogenic resources, the nurses may push Peter along the health continuum in the positive direction toward recovery and health. Based on the three datasets, we identified the following salutogenic resources: (1) connectedness to life, (2) feeling alive and present, (3) meaningfulness and purpose, (4) feeling valuable to someone, (5) practical solutions, (6) previous coping experiences, and (7) provoking and inspiring experiences [14, 16,17,18]. By means of creative approaches that support and enhance these salutogenic resources, Peter is pulled and pushed along the continuum, reaching the stage termed “In between.”

6.2 In Between

-

Peter was transferred to the ICU of a local hospital, where he eventually had secretion stagnation and therefore needed mechanical ventilation again. He has had high fever and severe diarrhea. Now he is recovering and the goal is to disconnect the ventilator, extubate him and let him breathe himself.

-

Observation:

-

The doctor on duty indicates that Peter can be allowed to breathe completely on his own. The nurse disconnects him from the ventilator, mucus is suctioned from the breathing tube into a bag and the air is removed from the cuff before the breathing tube in his throat is removed. A sterile compress is applied to the hole in his throat and Peter receives oxygen via a nasal cannula. The nurse sits down by his bed and can see that he’s breathing effortlessly. Then he opens his eyes and tries to focus on her. He coughs and the nurse puts her finger over the compress to prevent air leakage to enable him to cough more powerfully. Then he falls asleep again and he seems to be ok. Suddenly he wakes up, opens his eyes and turns his head.

-

Peter’s reflections (comprehensibility, meaning, manageability):

-

I’m not sure, really, if it was just when I came to or if it was in the coma phase itself ... I think it was when I was coming out of the coma that I felt very nervous ... and scared, but I also felt that things had kind of worked out all right. The fact that it was a bit up and down, that might be a way of reacting when you’re woken up again, I don’t know, it’s hard to say. … Yes, it was just like it was very hot and it was kind of a lousy feeling to be alive, as it was so hard ... that’s a bit weird.

-

The nurse’s reflections:

-

He seems to have a thousand questions in his head: “My God, who, what, where?” He realizes that I’m here and falls asleep again. He’s still so sick that he can’t relate to what we’re doing. He opens his eyes when we talk to him, but I don’t think he would say “I’m cold” of his own accord unless I asked him. He’s a man who’s been very sick and he’ll need a lot of help to get going again. Now he’ll be spending most of his energy on breathing and coughing and eventually communicating.

-

Today when I brushed his teeth, he opened his mouth and stuck out his tongue. Peter follows what I say, or tries to. I asked if he could answer “yes” or “no”, but I don’t know whether what he said was yes or no. But I don’t think he has the look of a person who’s completely out of it. He seems to be looking at me as if he’s asking: “What are you doing?” But I don’t feel that he’s afraid. Not now. He might be in a dream, who knows? I try to appeal to him and see if he reacts to anything. See if I can get a smile. I got one yesterday evening. I haven’t had one today.

In the “In between” phase, patients were awakened and became gradually more alert. However, at the same time they often experienced their body as amorphous and boundless, and some even felt that they were not human. The patients described this phase as marked by an existential threat and a feeling of being trapped. It was like living the worst horror movie with tiring delusions. Others found that vivid experiences in dreams ignited their willpower.

The ICU nurses were close to the patients during the awakening period (In between) and provided reassurance and well-being:

I remember they were turning me, talking and asking: ‘Are you lying comfortably now?’ and they had gentle and mild voices. That was all nice, really. My experience was that the nurses were very clever. They were confident in their work. It seemed like they knew what they were doing, no hesitation – that made me feel very safe!

However, the relatives were obviously most important to the patients, and were the first people they remembered when they woke up; they transformed “gloomy weather into a sunny day.” Family members were essential for the ICU patient to feel important and have future hopes.

I was happy every time they came. And they brought my five grandchildren from time to time, and that helps to get your spirits up too.

Although visits from family and friends were appreciated, there was a limit where the visit became burdensome. Several talked about the communication problems linked to being intubated. Others wanted someone to tell them how long it would take before they would make enough progress to move out of the ICU. Although this was not easy to predict, it would have reassured the patient if someone had talked about it and explained why they could not give a definite answer. It also seems important to find time to provide care to the patient’s relatives in the form of information and advice on how to support the patient.

6.3 Never in My Mind to Give Up

-

The nurse’s reflections:

-

Yesterday Peter was so alert that I went through what had happened with him again. Because if they’re capable of thinking in a phase like that, it must be a terrible experience to wake up and not understand anything, because I’m sure he doesn’t. So, I prefer to use short phrases like “It’s ok” and “You’re getting better”. Maybe you saw it today too: it’s hard to tell if he’s trying to say something or if he’s trying to swallow. And to make sure he doesn’t panic, I emphasized that he has a voice and that he’ll get it back and everything will be the way it was before.

-

Peter’s reflections (comprehensibility, meaning, manageability):

-

The doctor told me to try to scratch my nose and I couldn’t do it, only got half-way up with my index finger, I didn’t have the strength. Not a single muscle in my body was working then... I probably thought it was a lot easier than it was. Like if I just had a few more days, I could just get on my feet again and get a walker, but in fact it wasn’t that easy … There was nothing else in my head except to get up on my feet and be active again, that was all I thought about! ... I had good care and I was looked after properly by competent people, so I felt reassured that I was getting the best treatment you could get.

-

It was the progress I was making all the time ... and the words of the nurse: “When you finally turn the corner, you’ll really notice it and then things will really start to move”, and that’s what happened. Once I started to make progress, the first thing was stand in front of the bed for 20 seconds, then one step forward and one back and then I could take two steps forward and then I could walk round the room, and then finally I could walk by myself with the walker. So, it was the progress all the time that gave me the courage and motivation to make a bit more effort.

Clearly, disease and illness are more prominent than well-being among ICU patients. At the same time, both clinicians and relatives are striving for and looking (consciously or unconsciously) for signs of well-being in the patient. Our data also showed that many patients, despite serious illness, experience inner strength, meaning, comprehensibility, manageability, connectedness, hope, and willpower. The most important aspect of this phase from the patient’s point of view was that the salutogenic forces were not distrusted or contradicted (by nurses wishing to present the reality), even though the patient’s hopes, meanings and comprehensibility may have seemed completely unrealistic to doctors and nurses.

Most ICU patients felt safe, grateful, and satisfied with nurses and physicians. However, some experienced a lack of respect and understanding of their situation and too little information about things that were obvious to the staff, but not to the patient. Despite exhaustion, weakness and discomfort, most patients expressed no doubts about coming back to life. Their daily life in the ICU was both challenging and monotonous and one way to cope with it all was to dream about one’s future life.

6.3.1 How Do Family Members Support Patients?

For relatives it was important to be with the patient. Sitting close to a loved one was a burden for many of them, but they still wanted to be there. Family members described a specific sensitivity for the patient’s body language and needs, and for what was meaningful in the situation.

I had to keep an eye on things a bit. I don’t know anything about the medical stuff, about nursing and so on and what it takes to get him healthy, but I felt I had to be there anyway to ... make sure he didn’t miss anything. ... and then I had to do what I could to help him get better, putting skin cream on his legs when they were dry and so on. There wasn’t much I could do, but I do know he was pleased I was there!

And because Mom was producing a lot of mucus and she was on the ventilator for so long, they gave her a tracheostomy. And it was very difficult for Mom when she woke up that she had no voice. So, we had to explain that repeatedly.

The presence of family members was important because they could look ahead and encourage the patient by saying that this was something they would cope with together. Relatives knew what motivated the patient, such as family, a pet, a soccer game on television or talking about going hunting again. They could motivate and push the patient by saying: “If you’re going to get out of here, you have to keep going even though it’s hard.”

The patient’s experience of the presence of relatives was described as follows:

I could recognize her smell, I knew it. And she has a special way of doing things, in a way only she does, my brain managed to register that. It was very good for me. Small impulses that give me a good feeling ... like stroking my cheek. I didn’t hear any voices, just felt that touch!

I remember the visits made me very tired. But when my wife came, it was like I’d had gloomy weather for a long time and then suddenly there was a sunny day! You see? This happened every time she arrived!

6.3.2 How Do ICU Nurses Support Patients?

The nurses supported the patients by taking responsibility for both patients and visiting family members. The ability to “tune in” to the patient was important and was expressed through attention and sensitivity to the patient’s body language:

I don’t know if there’s anything we do subconsciously ... if we give the impression that we’ve given up or not? It’s kind of scary to think about ... whether they can feel that we believe they’ll pull through or not. We had a patient who said that everyone had kind of given up hope for her ... and she’d understood a lot of what was said. Afterwards, she said to the nurse who had said she would recover: ‘You were the one with the kind hands’. And then I thought: Is it possible, really? Do we convey things without realizing it?

In this case, the way the ICU nurse provided reassurance and well-being helped to promote the patient’s willpower to fight for recovery. The following case underlines the importance of knowing the patient:

Of course, we can often tell when the patient’s at the turning point. When you do familiar things like morning care and talk about everyday life, their children and their family, the dog for example, well then you make contact that may be good for the patient and help prevent delirium. Familiar things and loved ones are important to motivate patients to move forward. I think it’s important that it’s the same nurses who come back, so you can build on what we achieved yesterday, that has a positive effect. And that you have contact with the patient, that good relationship is very important. My daughter once said: ‘Oh, do you need to put on makeup before you go to work?’ I answered: ‘Well yes, because today I’m almost the only person the patient’s going to see.’ Not that it makes any difference, but ... we should believe in things for them many times, and we must push them. Some of them often don’t want to get up. And precisely that step of getting out of bed and into a chair seems quite out of the question when you’ve been in bed for weeks and can’t even lift your finger. But then we need to believe on their behalf: ‘Yes, but this is something we’ve got to do ... I understand you don’t want to, but it’s for your own good.’ Because we see that many times… we have to put in much more effort than they can manage themselves.

Knowing the patient seems important to create meaning. The good relationship and the nurse’s efforts in transferring belief and hope to the patient provided support in the rehabilitation process during the illness trajectory.

The above examples may be said to describe model cases. But nurses have also experienced actions that did not go according to plan. One experienced ICU nurse talked about a patient who was a well-known pianist:

Sometimes you think ... I’m sure this will be ok! … I remember once when I had a patient called Geir, who had been on the ventilator for a very long time, he was very depressed and heavy-hearted… and eventually he got a tracheostomy. Then I could take him around in a wheelchair, with his oxygen bottle and bag. I thought: he was a very well-known pianist, if I go round past the switchboard ... there’s a piano there ... then I can wheel him there ... then he can play! Music was his whole life! But it was just a big disappointment, because Geir couldn’t control his fingers properly. What I thought would be a great motivating factor ... it didn’t really work out too well.

That was a borderline case where the nurse tried to use the patient’s potential health-promoting resources. She regarded him as more than “just a patient,” realized his personal qualities and put in an extra effort to help him to “light the spark of life.” The patient was probably just as disappointed as she was, despite her good intentions and dedication. Oscillation between success and failure was typical of not only long-term ICU patients but also their nurses and their relatives.

6.3.3 Summing Up

Based on the three datasets from long-term ICU patients, their family members, and experienced ICU nurses, three stations along the ease/dis-ease continuum were identified: (1) The breaking point, (2) In between, and (3) Never in my mind to give up. Figure 18.2 portrays the health continuum, illustrating the three different stages along the pathway toward survival and health. Here we see how the ICU nurses make great efforts to relieve Peter’s ailments, such as pain, exhaustion, and tiring delusions. Using the identified salutogenic resources, the nurses and Peter’s family members are gently pulling and pushing him in the positive direction, toward survival and functioning.

7 Discussion

The aim of this study was to enhance understanding of the essence of long-term ICU care in a health promotion perspective. This means that nurses can be both generalized and specific resistance resources against the stress caused by ICU care. Further, they enable patients to find meaningfulness and gain control over their life situation. From the perspectives of former long-term ICU patients, their family members, and ICU nurses, this study provides insights into how salutogenic resources can be used to support and facilitate ICU patients’ existential will to keep on living. The salutogenic concepts of inner strength, meaning, connectedness, hope, willpower, and coping are central and form part of the essence of salutogenic long-term ICU care. Below we will discuss the benefit of ICU nurses using a health promotion perspective to support care based on the ABCDEF bundle in relation to a tentative theory of salutogenic long-term ICU nursing care.

7.1 The ABCDEF Bundle, Health Promotion, and the Missing Salutogenic “G”

Although intensive care has made great strides in recent years [4], patients and their relatives may experience discomfort and mental and physical health symptoms as a result of examinations, treatment, and the way clinicians relate to them [5, 63]. According to Ely [5], this may partly be due to an ICU culture where physicians and nurses have focused strongly on the technical aspects of patient care at the expense of patients’ dignity, self-respect and identity: “The most productive aspect of the philosophy of ICU liberation for us as clinicians is that it shifts our focus from the monitors, beeps, and buzzers to a human connection” ([5], p. 327). In recent years, international research has therefore called for a shift in ICU culture from heavy sedation and the use of restraint to more open units with patients who are more alert and active [5], and where relatives are given a more active role in patient care [63].

After the patient is stabilized, evidence-based measures in the form of the ABCDEF bundle are recommended. “The ABCDEF bundle is a tool to promote the assessment, prevention, and integrated management of pain, agitation, and delirium, while also facilitating weaning from mechanical ventilation and maximizing early mobility and exercise and family engagement and empowerment” [6]. This bundle is an international framework aiming at flexibility and the incorporation of new evidence-based recommendations. Although an important goal of intensive care is to reduce pain, anxiety and ICU delirium threatening the patient’s dignity and self-respect, it appears difficult to achieve this in practice [5]. Ely argues that the ABCDEF bundle is not a cookbook recipe, but requires lasting changes bedside, where the implementation process must include both philosophy and culture ([5], p. 326). Important barriers to ABCDEF bundle compliance are; patient safety, lack of knowledge, workload, turnover (clinicians and managers), poor staff morale, and lack of respect between the professional groups involved in implementing the bundle [6].

In the ICU, points B and E are emphasized as particularly important, meaning that the patient receives pain relief, has minimum or no sedation, and is mobilized despite still being on mechanical ventilation ([5], p. 325). However, our study shows the importance of providing good clinical nursing, the missing salutogenic “G,” where ICU nurses know the patient, include the family (F) and know which salutogenic resources are important to long-term ICU patients. This is, however, often underestimated as a health promotion factor in the ABCDEF bundle. The ICU nurse’s skills in tuning in to the needs of the patient and relatives and in focusing on salutary factors are regarded as important generalized resistance resources (GRR) that can strengthen patients’ SOC and resilience at the physical, psychological, and spiritual levels ([21, 64], p. 289).

7.2 A Tentative Theory of Salutogenic ICU Nursing Care

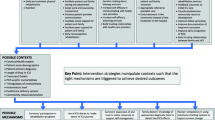

The tentative theory [65] of ICU nursing care has five main concepts: (1) the long-term ICU patient pathway, (2) the patient’s inner strength and willpower, (3) salutogenic ICU nursing care, (4) family care, and (5) pull and push. In Fig. 18.3 we suggest a structure of the phenomenon that includes essential concepts describing the health promotion process of long-term ICU care and suggested relationships among the concepts. The concepts of the tentative theory, shown in Fig. 18.3, indicate that the patient goes through three stages (The breaking point, In between, and Never in my mind to give up), and can potentially experience inner strength and willpower in all the stages. Family care and nursing care represent key salutogenic resources for the patient’s trajectory. The salutogenic resources are linked to the concept of pull and push factors. Pull factors help/entice the patient toward an existential “here” (connectedness, meaning, well-being) to enable nurses and relatives to gradually push (encourage) the patient in the continued ICU trajectory.

7.3 The Long-Term ICU Patient Pathway: SOC and GRRs

The SOC and GRRs are key concepts that are interrelated in the salutogenic model. But how can we understand the SOC and the salutogenic concept of manageability in ICU patients where fatigue and serious illness requiring life support mean that their bodies are dependent on and connected to ventilators and invasive catheters? What is the relevance of the salutogenic concepts of “meaning” and “comprehensibility” for patients who are totally exhausted and sometimes hallucinating, having experiences of travelling, flying, standing upside down and not knowing where their body begins and ends? For many intensive care patients, these are frightening experiences that are not “comprehensible” and have no “meaning.” Some patients deal with the situation by withdrawing into themselves, while others become very agitated, fight against the ventilator, pull the endotracheal tube and want to get out of bed at the risk of disconnecting vital equipment. In such situations, it is common in many countries to tie patients down [66] and/or use sedatives [67]. Both measures are debated, because they are considered as abuse and because they make patients passive and thus prolong ventilation, leading to an increased risk of complications [68].

Below, we argue that both family members and nurses represent important salutogenic resources to support and facilitate manageability, meaningfulness and comprehensibility to help patients through their stay in the ICU. But firstly, we will show that, despite their disease, delusions, exhaustion, and fatigue, long-term ICU patients have important salutogenic resources (GRRs) themselves.

7.4 Patients’ Inner Strength and Willpower

Previous studies have shown experiences on the borders of consciousness to be filled with personal meaning as well as healing potential [60,61,62]. In the present study, long-term ICU patients also told about experiences at the borders of unconsciousness that represented both personal meaning and vitalizing energy. They experienced meeting deceased relatives in their dreams or delusions. Initially, the ICU patients perceived the meeting as if the deceased relatives had come to fetch them, which was felt to be liberating. But without verbal communication, they immediately understood this as a message that seemed to represent a turning point at which the patients were pushed to make a choice about life and death, and an experience of, after all, having inner strength and willpower to go on living. This salutogenic perspective of the ICU patients’ dreams and delusions as having healing potential represents a complementary view to the pathogenic perspective that interprets delusional experiences as a symptom of ICU delirium [69].

7.5 Salutogenic ICU Nursing Care

Nursing care is to be concrete and present in a relationship where nurses use their senses and bodies. This implies that nurses direct attention away from themselves and toward patients in such a way that patients receive help, feel respected, and enabled to become participants in their own lives.

ICU nurses have close contact with their patients, and in Norway they are responsible for the practical everyday care of patients. Practical nursing, including everyday personal hygiene, provides ample opportunity for clinical observations and for the nurse to assess and respond to changes in the patient’s situation. In the close care relationship lies the potential to get to know the patient and build trust. Trust can be built by looking attentively at the patient, being sensitive to the patient’s body language and by handling the patient gently and correctly. From the perspective of the phenomenology of the body [70], this involves “pulling” the patient to an existential “here,” by the nurse creating a situation where the patient can experience connectedness and meaning in meaninglessness (cf. “gentle hands” and the patient’s feeling of hope).

Nurses are recommended to design interventions to enhance the SOC in early phases of hospitalization for patients [64]. Losing the feeling of one’s own body is common among ICU patients, as in the story about Peter. “Without” a body, finding meaningfulness in life might prove difficult. The nurse’s touch can help the patient to realize the limits of where the body begins and where it ends. Further, in personal hygiene situations it is important that the nurse includes the patient and encourages the use of the body again such as in brushing teeth and assists the patient with body movements (cf. “meaningfulness” and “comprehensibility” in the story about Peter). For the patient who is bedridden and attached to equipment, it provides hope and meaning to feel the floor under one’s feet. The nurse can “ground” patients by helping them to sit on the edge of the bed with their feet on the floor, or by offering patients the use of a bed bike so that they can feel resistance in their legs and perform familiar bodily movements, cf. “manageability.” It seems important to let the body do what it is meant to do (Table 18.2). Anything familiar seems health promoting, whether it be a familiar sound, smell, voice, touch, movement, or presence. Allowing for patient participation to help patients perceive life as comprehensive, manageable and meaningful is central in salutogenic ICU nursing care [21, 71]. Building a relationship with the patient and thereby gaining insight into the patient’s dreams and future plans (impacting meaningfulness, hope, and willpower) can be health-promoting when the nurse encourages patients and helps them to keep those dreams alive through the challenges of gradual rehabilitation, such as mobilization and ventilator weaning.

Since early 1990s, nurses in Norway started writing diaries for ICU patients to offer patients a tool for processing memories of their ICU stay [72]. Diaries are valuable for both patients and their family members [73] and were in a methasynthesis found to decrease anxiety and depression and improve health-related quality of life among ICU survivors [74]. One explanation might be that the diary has the potential to give a better understanding of the ICU periode by providing an opportunity for discovery of meaning in experiences and memories. Finding existential meaning seems to be of decisive significance for how far people reach in their lives after having lived through intensive care treatment [80].

7.6 Family Care

The present study illuminates how family members are key to the patient’s breakthrough because their actions are tailored to the patient’s specific personality as well as the patient’s lifeworld [17]. The presence of family members helps to awaken and release the patient’s inner strength, which has the potential of providing a turning point and breakthrough to life. In the perspective of the body as interpretive and meaningful [70], also at the breaking point between life and death, the ICU patient might sense the situation to be more comprehensible, manageable and meaningful in the presence of family members.

The presence of a family member means that the patient hears a familiar voice, smells a scent that evokes pleasant memories and feels a familiar hand. Such experiences are resources that can embolden the patient ([44], p. 174) and thus stimulate the patient’s inner strength and will to survive. Familiar faces, voices and smells, and a familiar and gentle hand, can help to reassure the patient and make the situation more manageable. The presence of family members provides comprehensibility through their behavior: their forms of communication and their recognition, interpretation, and acknowledgement of the patient’s body language.

A meta-analytic review shows that people with stronger social relationships have a 50% greater likelihood of survival than those who have weaker social relationships [75]. In the cross-disciplinary field of psycho-neuro-endocrine-immunology, interaction has been found between biological, genetic, and environmental factors [76]. Studies show that one impact of close relationships on health is through inflammatory response [77]. When people are ill, it is hypothesized that the risk for mortality increases substantially when they lack social support [78]. The importance of social contact is not easy to quantify, but a study of cardiac patients showed that social support reduced the negative effects of stress on their mental and physical well-being [79]. Flexible visiting hours for relatives in ICUs appear to reduce delirium and symptoms of anxiety among patients and increase family member satisfaction [80]. In summary, being socially connected affects psychological and emotional well-being, and has a significant positive effect on physical well-being and survival [78]. ICU nurses thus have an important part to play in including relatives and facilitating their presence in the ICU.

7.7 Pull and Push

When the patient is “at breaking point” between life and death, the relationship to family members is important. Knowing the patient was essential to understand what she or he was trying to express [17]. Pull factors involve linking the patient to an existential “here” (connectedness, meaning, well-being), which will enable nurses and relatives to gradually push (encourage) the patient to progress in the ICU trajectory. This study shows that nurse–patient interaction based on the ICU nurse’s attunement and sensing can help to provide an understanding of the patient’s situation, by acknowledging the patient through eye contact, gentle touch and telling news from home.

8 Limitations

How can we determine whether the description of the phenomenon of health promotion in long-term ICU nursing care is valid and relevant? Nurse and professor Karin Dahlberg [49] states that an essence or structure is what constitutes a phenomenon. She uses the horse as an example and asks: What makes a horse a horse, and not a donkey or a mule? Although horses may be large or small and be of many different colors, there is something essential about the horse that makes us immediately realize that a particular animal is a horse. A phenomenon is not mysterious or hidden, but something we immediately see and understand. Essence is not something we add to research; it is not the researcher who makes the phenomenon meaningful. The essence is already there, in the intentional relationship between us and the phenomenon, between nurse and patient, between patient and relatives ([49], p. 249).

In this chapter, therefore, we have focused on presenting descriptions containing various nuances and aspects from the ICU context. The starting point has been the particular and the concrete. Since every phenomenon is related to everything else in the world, it is sometimes difficult to see the specific phenomenon one is looking for. Dahlberg refers to Merleau-Ponty [70] in stating that all phenomena and meanings are interconnected and that it can be difficult to see where one phenomenon ends, and another begins. To return to the horse: although the variety of horses is endless, there is a kind of model that sets a limit, an essence that says that this is a horse and not a mule. It is a general form, an essential meaning or essence that makes the phenomenon what it is. If the essential meaning changes, it is another phenomenon [49]. Many clinicians already know the essence of long-term ICU nursing care, and how a health promotion approach is already an integral part of the ICU context. For this reason, many ICU nurses can identify factors of particular importance to patients and take appropriate health-promoting measures. For others, such as intensive care students and less experienced ICU nurses, the theoretical analysis and tentative theory in this chapter may lead to reflection on their role and enable them to view their practice in a new light.

A potential weakness of this study is that we as researchers and ICU nurses belong to the same world as the phenomenon we have explored. Consequently, it can be difficult to separate the phenomenon from its context, but also to separate ourselves from the phenomenon. Using phenomenological reduction, which Dahlberg calls “bridling,” we have employed critical reflection to discuss “what we take for granted,” such as our clinical experience and our theoretical perspective.

A potential strength of this study is that a health promotion approach in ICU nursing is in line with the new paradigm in ICU care where the trend is toward a greater number of awake patients [81,82,83], with minimal or no sedation [84]. This will further challenge interaction and communication with patients [85]. With the aim of helping patients through the ICU stay, we thus consider it a strength that our empirical data include the voices of the patient, relatives and ICU nurses.

9 Conclusion

Few patients are as helpless and totally dependent on nursing as ICU patients. How the ICU nurse relates to the patient is of vital importance to the patient, both mentally and physically. Even if nurses provide evidence-based care in the form of minimum sedation, early mobilization and attempts at spontaneous breathing during weaning, the patient may not have the strength, courage and willpower to comply. From the perspective of former long-term ICU patients, their family members and ICU nurses, this study provides insights into how salutogenic resources can be used to support and facilitate ICU patients’ existential will to keep on living. The salutogenic concepts of inner strength, meaning, connectedness, hope, willpower and coping are of vital importance and form part of the essence of salutogenic long-term ICU nursing. The ICU nurse has independent responsibility to include family members in care and thus plays a key role in coordinating and implementing evidence-based measures for patients in a health promotion perspective.

The tentative theory of salutogenic long-term ICU nursing care presented here has five main concepts: (1) the long-term ICU patient pathway, (2) the patient’s inner strength and willpower, (3) salutogenic ICU nursing care, (4) family care, and (5) pull and push. These concepts show that the patient goes through three stages (The breaking point, In between, and Never in my mind to give up), in all of which the patient potentially experiences inner strength and willpower. Family care and nursing care represent vital salutogenic resources for the patient, and a key concept related to these resources is that of “pull and push.” Pull factors involve facilitating/enticing/linking the patient to an existential “here” (connectedness, meaning, well-being), which will enable nurses and relatives to gradually push (encourage) the patient to progress in the ICU trajectory.

This tentative theory can be used to reflect on one’s own clinical practice, and in teaching intensive care students and in research.

Take Home Messages

-

ICU patients who need mechanical ventilation are unable to talk and need fundamentals of nursing care. They are therefore totally dependent on others, including having others interpret their symptoms and feelings. This means that advanced medical treatment and technology need to be accompanied by advanced nursing care.

-

There is growing evidence to suggest that the ABCDEF bundle (A, assess, prevent, and manage pain; B, both awakening and spontaneous breathing trials; C, choice of analgesic and sedation; D, delirium: assess, prevent, and manage; E, early mobility and exercise; and F, family engagement and empowerment) improves ICU patient-centered outcomes and promotes interprofessional teamwork and collaboration. However, this chapter entails that the bundle misses the salutogenic “G.”

-

This chapter shows the importance of salutogenic ICU nursing care, termed “the missing G,” where ICU nurses know the patient, include the family, and uses salutogenic resources to promote long-term ICU patients’ inner strength, health, survival, and well-being.

-

The ICU nurse’s skills in tuning in to the needs of the patient and relatives and in focusing on salutary factors represent vital generalized resistance resources (GRR) that can strengthen patients’ SOC, resilience and well-being physically, psychologically, and spiritually.

-

A shift from technical nursing toward an increased focus on patient understanding, and greater patient and family involvement in ICU treatment and care is needed.

-

This chapter is based on the three datasets from long-term ICU patients, their family members and experienced ICU nurses, and three stations along the ease/dis-ease continuum were identified: (1) The breaking point, (2) In between, and (3) Never in my mind to give up.

-

The tentative theory of salutogenic long-term ICU nursing care includes five main concepts: (1) the long-term ICU patient pathway, (2) the patient’s inner strength and willpower, (3) salutogenic ICU nursing care, (4) family care, and (5) pull and push. These concepts demonstrate that the long-term ICU patient goes through the three stages (The breaking point, In between, and Never in my mind to give up), during which the patient potentially experiences inner strength and willpower.

-

Family care and nursing care represent vital salutogenic resources for the patient, and a key concept related to these resources is that of “pull and push.” Pull factors involve facilitating/enticing/linking the patient to an existential “here” (connectedness, meaning, well-being), which will enable nurses and relatives to gradually push (encourage) the patient to progress in the ICU trajectory.

-

The salutogenic concepts of inner strength, meaning, connectedness, hope, willpower, and coping are the central essences of salutogenic long-term ICU care.

References

Phua J, Weng L, Ling L, Egi M, Lim CM, Divatia JV, et al. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):506–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30161-2.

Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574–81.

Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K, Brunkhorst FM, Graf J, Troitzsch U, et al. Rehabilitation interventions for postintensive care syndrome: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1263–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000148.

Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75.

Ely EW. The ABCDEF bundle: science and philosophy of how ICU liberation serves patients and families. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):321–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002175.

Stollings JL, Devlin JW, Pun BT, Puntillo KA, Kelly T, Hargett KD, et al. Implementing the ABCDEF bundle: top 8 questions asked during the ICU liberation ABCDEF bundle improvement collaborative. Crit Care Nurse. 2019;39(1):36–45. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2019981.

Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, Thompson JL, Aldrich JM, Barr J, et al. Caring for critically ill patients with the ABCDEF bundle: results of the ICU liberation collaborative in over 15,000 adults. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):3–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003482.

Egerod I, Kaldan G, Lindahl B, Hansen BS, Jensen JF, Collet MO, et al. Trends and recommendations for critical care nursing research in the Nordic countries: triangulation of review and survey data. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;56:102765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2019.102765.

Ciufo D, Hader R, Holly C. A comprehensive systematic review of visitation models in adult critical care units within the context of patient- and family-centred care. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2011;9(4):362–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1609.2011.00229.x.

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):103–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169.

Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1121–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882.

Al-Mutair AS, Plummer V, O'Brien A, Clerehan R. Family needs and involvement in the intensive care unit: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(13–14):1805–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12065.

Eriksson M, Lindstrom B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. J EpidemiolCommunity Health. 2006;60(5):376–81.

Alexandersen I, Stjern B, Eide R, Haugdahl HS, Engan Paulsby T, Borgen Lund S, Haugan G. “Never in my mind to give up!” A qualitative study of long-term intensive care patients’ inner strength and willpower-promoting and challenging aspects. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(21–22):3991–4003. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14980.

Haugdahl HS. Mechanical ventilation and weaning: roles and competencies of intensive care nurses and patients’ experiences of breathing. Doctoral thesis. UiT The Arctic University of Norway; 2016.

Haugdahl HS, Dahlberg H, Klepstad P, Storli SL. The breath of life. Patients’ experiences of breathing during and after mechanical ventilation. Intens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;40:85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.01.007.

Haugdahl HS, Eide R, Alexandersen I, Paulsby TE, Stjern B, Lund SB, Haugan G. From breaking point to breakthrough during the ICU stay: a qualitative study of family members’ experiences of long-term intensive care patients’ pathways towards survival. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(19–20):3630–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14523.

Haugdahl HS, Storli SL. ‘In a way, you have to pull the patient out of that state ...’: the competency of ventilator weaning. Nurs Inq. 2012;19(3):238–46.

Antonovsky A. Health, stress, and coping. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass; 1979.

Antonovsky A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot Int. 1996;11(1):11–8.

Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, Bauer GF, Pelikan JM, Lindström B, Espnes GA. The handbook of salutogenesis. Berlin: Springer; 2017.

Martinsen K. Omsorg, sykepleie og medisin: historisk-filosofiske essays [Care, nursing and medicine]. Oslo: TANO; 1989.

Martinsen K. Care and vulnerability, vol. 1. Oslo: Akribe; 2006.

Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987.

Lindström B, Eriksson M. The Hitchhiker’s guide to salutogenesis: salutogenic pathways to health promotion. Helsinki: Folkhälsan Research Centre; 2010.

Idan O, Eriksson M, Al-Yagon M. The salutogenic model: the role of generalized resistance resources. In: Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, Bauer GF, Pelikan JM, Lindström B, et al., editors. The handbook of salutogenesis. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG; 2017. p. 57–70.

Bonebright CA, Clay DL, Ankenmann RD. The relationship of workaholism with work–life conflict, life satisfaction, and purpose in life. J Couns Psychol. 2000;47(4):469.

Fry P. The unique contribution of key existential factors to the prediction of psychological well-being of older adults following spousal loss. Gerontologist. 2001;41(1):69–81.

Melton AM, Schulenberg S. On the measurement of meaning: logotherapy’s empirical contributions to humanistic psychology. Humanist Psychol. 2008;36(1):31–44.

Haugan G. Meaning-in-life in nursing-home patients: a valuable approach for enhancing psychological and physical well-being? J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(13–14):1830–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12402.

Pearson PR, Sheffield B. Psychoticism and purpose in life. Pers Individ Diff. 1989;10(12):1321–2.

Chan DW. Orientations to happiness and subjective well-being among Chinese prospective and in-service teachers in Hong Kong. Educ Psychol Rev. 2009;29(2):139–51.

Halama P, Dedová M. Meaning in life and hope as predictors of positive mental health: do they explain residual variance not predicted by personality traits? Stud Psychol. 2007;49(3):191.

Ho MY, Cheung FM, Cheung SF. The role of meaning in life and optimism in promoting Well-being. Pers Individ Diff. 2010;48(5):658–63.

Holahan CK, Holahan CJ, Suzuki R. Purposiveness, physical activity, and perceived health in cardiac patients. Disabil Rehabil Literature. 2008;30(23):1772–8.

Kleftaras G, Psarra E. Meaning in life, psychological well-being and depressive symptomatology: a comparative study. Psychol Health. 2012;3(4):337.

Skärsäter I, Rayens MK, Peden A, Hall L, Zhang M, Ågren H, Prochazka H. Sense of coherence and recovery from major depression: a 4-year follow-up. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23(2):119–27.

Zirke N, Schmid G, Mazurek B, Klapp BF, Rauchfuss M. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence in psychosomatic patients-a contribution to construct validation. Psychosoc Med. 2007;4:Doc03.

Li W, Leonhart R, Schaefert R, Zhao X, Zhang L, Wei J, et al. Sense of coherence contributes to physical and mental health in general hospital patients in China. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(5):614–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2014.952644.

Nygren B, Alex L, Jonsen E, Gustafson Y, Norberg A, Lundman B. Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):354–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360500114415.

Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and its relation with quality of life: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(11):938–44.

Surtees P, Wainwright N, Luben R, Khaw K-T, Day N. Sense of coherence and mortality in men and women in the EPIC-Norfolk United Kingdom prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(12):1202–9.

Buber M. On intersubjectivity and cultural creativity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1992.

Martinsen K. Fra Marx til Løgstrup. Om etikk og sanselighet i sykepleien [From Marx to Løgstrup]: TANO A.S.; 1993.

Hoeck B, Delmar C. Theoretical development in the context of nursing-the hidden epistemology of nursing theory. Nurs Philos. 2018;19(1) https://doi.org/10.1111/nup.12196.

Duncan C, Cloutier JD, Bailey PH. Concept analysis: the importance of differentiating the ontological focus. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58(3):293–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04277.x.

Mikkelsen KB, Delmar C, Sørensen EE. Fundamentals of care in time-limited encounters: exploring strategies that can be used to support establishing a nurse-patient relationship in time-limited encounters. J Nurs Stud Patient Care. 2019;1:8–16.

Risjord M. Nursing knowledge. Science, practice, and philosophy. London: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

Dahlberg K, Dahlberg H, Nyström M. Reflective lifeworld research. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2008.

Van Manen M. Phenomenology of practice : meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing, vol. 13. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press; 2014.

Smith MJ, Liehr PR. Middle range theory for nursing. Berlin: Springer; 2018.

Lundman B, Alex L, Jonsen E, Norberg A, Nygren B, Santamaki Fischer R, Strandberg G. Inner strength—a theoretical analysis of salutogenic concepts. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(2):251–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.05.020.

Frankl VE. Man’s search for meaning. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1985.