Abstract

Real world learning and the internationalisation of curricula are relatively new considerations in contemporary higher education discourses. Inquiry and application lie at the heart of real world learning, and the internationalisation of academic programmes is expected to equip learners with diverse learning styles and global citizenship skills. However, combining these two sets of educational objectives for pedagogic success is challenging, mainly because of learners’ academic, social and cultural differences. The chapter addresses this problem theoretically and with the help of three real cases drawn from the UK and Bangladesh. The cases convey the ethos and procedures for accommodating diversity, inquiry, application of learning, and cross-cultural collaboration in international educational settings. The findings suggest several practical guidelines on creating authentic and long-term learning opportunities in higher education.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Real World Learning in the Changing Landscape of Higher Education

Nineteenth-century American educational reformer Horace Mann’s proclamation of education as the ‘great equaliser of the conditions of men’ has a wider meaning in contemporary educational policies and practices (Mann, 1957). The dramatic expansion of knowledge domains in present-day academic disciplines, and enhanced explanations of the connection between learning and its applications, show strengths of formal education in every sphere of human life. The importance of higher education is significant as it is often associated with people’s earning, living standards and roles in sociopolitical actions. Because of the strong focus on subject specialisation and employability, higher education is goal-oriented in terms of the meanings and applications of the learning it delivers to students and other stakeholders.

Applications of the learning gained from higher education can be diverse, for example, in areas of research, employment, further education, cultural networking, and political negotiation. Hence, ensuring versatility in the learning and teaching activities, or in the overall term curriculum, is often challenging because it requires geographically relevant and culturally acceptable educational practices. For this reason, higher education academic programmes are generally expected to address both local and international sources of information, their transferability to different sociocultural constructs, and practical considerations regarding potential implications of the knowledge and skills transfer across borders. The expression ‘real world learning’, with its literal meaning, echoes these requirements indicating learning as a context-bound, culture-oriented, and applied practice.

Real world learning is relatively a new lingo increasingly being used in the education literature referring to students’ authentic and positive learning experiences. Researchers, for example, Rau, Griffith, and Dieguez (2019); Sharma, Charity, Robson, and Lillystone (2018); and Marriott, Tan, and Marriott (2015) have used other terms like experiential learning, applications of learning for individual development, discipline-led experience, and concrete experience to mean real world learning. The approach is partly comparable with some traditional academic models, for example, problem-based learning, service learning, and project-based learning (Boss, 2015; Brundiers, Wiek, & Redman, 2010). Real world learning has not yet become a distinguishable pedagogic paradigm, but its various unique features are developing, which offer insights into its principles and power in higher education.

Real world learning is a fresher attention at tertiary-level education compared to its sustained presence in primary and secondary school curricula for long time (Maxwell, Stobaugh, & Tassell, 2015). While there has been a continuous emphasis on critical, reflective and practice-based learning at universities in the past five decades, currently there is an increasing focus on various applied forms of education to facilitate real world learning experiences. The term ‘applied’ is self-explanatory, which generally indicates the practical use or applications of learning (Ovenden-Hope & Blandford, 2017). However, the educational policies and academics may consider the applications of learning from two standpoints: (1) learning by doing or facilitating teaching/learning through ‘incorporating applications’ of specific learning points (2) and preparing students with the knowledge and skills for ‘future applications’ of learning. On the one hand, ‘incorporating applications’ refers to applied pedagogic actions, for example hands-on practice or student-learning activities based on authentic educational content. On the other, ‘future applications’ highlight the knowledge and skills that students gain through educational experiences and for the purpose of application in defined areas, mainly in professions and work.

Conceptualising Real World Learning in Internationalised Curricula

There are many examples of international academic mobility in higher education during the early years of the very old universities. Nalanda Mahavihara, a monastic university founded in the fifth century in India, attracted thousands of foreign students from distant Buddhist world, such as China, Korea and Japan (Barua, 2016). Historical records, for example the travelogue of a Chinese visitor called Xuanzang, describe the exclusive lifestyle and academic culture of the foreign students who travelled across many countries to study theology, languages and medicine at this ancient university (Pinkney, 2015). There are also instances of policy-level consideration for international students at such academic institutions. For example, Emperor Frederik Barbarossa in his ‘Authentica Habita’ document, published in 1158, discussed the aspects of freedom for foreign students studying at the University of Bologna in Italy (Otterspeer, 2008). Although various international elements have been prevalent in higher education since the beginning of universities, specific discussions on the internationalisation of academic programmes started to become popular only in 1980s with enhanced awareness and deliberations on global cultures, quality of education, and options for employment. Presently, many universities are placing an emphasis on international collaboration for strengthening teaching, research and the recruitment of international students to generate revenue. According to the forth Global Survey Report of the International Association of Universities, about 75% of 1300 institutions in 131 countries have internationalisation agenda in their core strategies (Egron-Polak & Hudson, 2014). This indicates a worldwide recognition about developing curricula that match academic and professional requirements of both local and international stakeholders.

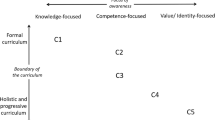

Internationalisation in higher education is broadly the amalgamation of “intercultural and international dimensions into the curriculum” (OECD, 2004, p. 7). It connects local and global cultures together and have impacts on major curricular areas, such as teaching methods, academic support, assessment, and learning gain (Leask, 2015). The key aim of the internationalisation is to enable “knowledge of self, and of self in relation to others, and seeing personal change as a necessary precursor to social change” (Clifford & Montgomery, 2015, p. 48). Because of these demands, internationalised academic programmes need to be external-facing, or linked to the real world, where students are treated as cultural agents and learning is a context-bound process. That is why an international curriculum targeted for real world learning is expected to enable students to become global citizens who learn and apply their knowledge and skills with considerations of diverse social, academic and employment contexts. The concept map (Fig. 6.1) illustrates some fundamental objectives of real world learning, such as enhanced awareness of global cultures, efficient intercultural communication skills, and strong capacity to think critically in the perspective of international academic programmes. The concepts drawn in the map emerged while we, the authors of this chapter, were reflecting on our personal teaching and educational research experiences linking with the value of real world experiences and external-facing curricula (see the conclusion chapter for the procedure we followed). Although the concept map is based on our personal experiences and professional beliefs, it widely denotes two contemporary and overarching focuses of the internationalised curricula: roles and impacts of globalisation, and the effects of teaching and learning on such global curricular features (Vishwanath & Mummery, 2019).

The educational notions depicted in the concept map offer the following four thematic areas associated with real world learning in the context of internationalised curricula, or more precisely international academic programmes.

- Ethos::

-

students are global citizens and work-ready with essential employability skills

- Purposes::

-

to build awareness of cultural diversity, help students transfer learning across borders and to different professions

- Methods::

-

culture-rich and applied pedagogies, coaching, collaboration, communication

- Learning gain::

-

curiosity and confidence, critical thinking and decision-making skills, employment skills, global citizenship skills, ability to incorporate different learning styles

We must acknowledge that the integration of these academic elements in higher education for improved learning experiences is not a brand-new idea. Rather, there is ample evidence suggesting their full or partial implementation. In the following section, we discuss three features of real world learning in international academic programmes. With reference to original case studies, we explore if the associated teaching and learning practices provide any pedagogic guidelines suitable for greater higher education sector.

Real World Learning in Action: An Evidence-based Discussion

The relationship between real world learning and global citizenship is crucial in international curricula. From a philosophical standpoint, true global citizens do not confine knowledge within conservative and nationalistic ideologies; rather they tend to see the validity of the knowledge from disparate social, economic, and cultural angles of vision. For example, while conducting a scientific experiment, students with the spirit of global citizenship are expected to acknowledge its wider impacts in different locations. They also try to contextualise foreign events, examples, and methodological approaches, for instance a teaching or learning strategy, in their learning. This feature in the curricula and pedagogies supplies them the opportunity to reflect and think critically and, at the same time, encourages them to relate learning to professional practices. Presently, the greater availability of technological resources has opened the door for students and academics to compare and contest individual views with divergent cultural entities within and beyond local contexts. Therefore, it is now less difficult to materialise external-facing curricula which are adequately inclusive, particularly through their connections with different locations, cultures, and people’s views.

The following sections contain three case studies, collected from UK and Bangladeshi universities, which evidence how students develop themselves to be global citizens through some carefully designed academic interventions. The UK and Bangladesh are two geographically and economically dissimilar countries, but it is interesting to notice their uniformity in terms of educational aims towards real world learning and internalisation of academic programmes.

Accommodating Diversity and ‘Wider’ Application of Learning

Curriculum is an umbrella term covering almost every philosophical and practical aspect of formal education, including teaching methods, learning approaches, educational resources, and academic development strategies. Different higher educational institutions may consider their respective curriculum unique because of individual viewpoints and emphasis, but the overall expectations have a common ground. For example, contemporary universities generally want their curricula to facilitate critical and reflective practices and prepare students to deal with local and global challenges. Additionally, students are expected to gain specialised academic and professional competencies, contributing to the creation of educated workforce needed for a healthy economy and knowledge-based society.

International elements in higher education can potentially offer enhanced learning outcomes, including better language skills, and intercultural communication and networks (Jibeen & Khan, 2015). The approach has strengths to improve one’s career prospects, especially if the required knowledge and skills are needed in target socio-economic and employment situations. Besides, from the higher educational institution point of view, internationalised learning culture can bring reputation and improve quality of academic programmes through increased global competitions and financial sustainability with the help of external sources of funding. Because of these multifaceted features, internationalised curricula in higher education can address the following two academic expectations:

-

1.

the teaching and learning are accessible and suitable for international audiences, such as students, faculty members, and researchers; and

-

2.

the educational outcomes can accommodate and be transferred to diverse global settings, for example the economic activities and job market in a particular country or region

Apart from preparing local students as global citizens, universities are also supposed to be welcoming to international students with different cultural backgrounds and economic classes. They should try creating inclusive educational environment and practical support systems to enable learning for all. In an international academic environment, providing language support is a prerequisite if the medium of instruction is different from students’ first language. Similarly, essential training on academic conventions and standards need to be facilitated for those coming from different learning cultures. In addition to helping students to attune in new educational environment, the curricula need to have the provision for building capacity to transfer knowledge and skills to various social and economic circumstances. University graduates are generally expected to contribute to the national development programmes, which may vary in countries and regions. Therefore, higher education curricula should be able to help students become strategic while designing and implementing initiatives that fit in local cultural expectations. The following case study taken from a Bangladeshi university describes two academic programmes designed for international students and their future involvement in national and regional development initiatives.

Case Study 1

Pathways for Promise and Access Academy (Nazmul Alam, Associate Professor and Head of Public Health, Asian University for Women, Bangladesh, and AKM Moniruzzaman Mollah, Professor of Biological Sciences and the Head of Science and Math Programmes, Asian University for Women, Bangladesh)

The Asian University for Women (AUW), a regional university based in Chattogram, Bangladesh, is dedicated to nurture the next generation of leaders for Asia and the Middle East. AUW offers academic programmes to promising young women from various cultural, religious, ethnic, and socio-economic backgrounds. It follows a liberal arts curriculum at pre-collegiate and undergraduate levels in social science and science disciplines. The education programmes combine leadership training, professional development and mentoring, and footing in critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Two pre-undergraduate programmes, namely Pathways for Promise and Access Academy, prepare students in English, Mathematics, and critical reasoning skills in the liberal arts tradition. All academic programmes taught in English and the academic environment are supportive to enable multiculturalism in the campus and residential life. In 2019, the university had students from 17 Asian countries representing many ethnic backgrounds.

A major challenge at AUW has been to ease the transition for international students coming from different education systems, languages of instruction and curriculum patterns. This challenge is even critical given AUW’s noble mission to teach young women from the underprivileged communities where English and quantitative skills at admission are a major issue. To address the problem, in 2008, AUW started ‘Access Academy’, a one-year programme to standardise English, mathematics, and critical reasoning skills before students start their undergraduate studies (AUW, n.d.). In 2016, the university introduced a flagship programme called ‘Pathways for Promise’, which offers an English-language intensive course for preparing students to study in the Access Academy programme. As a result of this spanning course, it has been possible for the Pathways programme to recruit young women from the ready-made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh (Jahangir, 2016), from the Rohingya refugee communities in Bangladesh and Myanmar, and from Afghanistan, Palestine, and Yemen for tertiary-level education.

International academic programmes in higher education generally aim to improve students’ awareness of other cultures and values. However, the risk of this objective is that the students may not have adequate opportunities to deal with their own contexts and cultures (Leask, 2015). Pathways for Promise and Access Academy programmes have created the space for combining students’ own social and cultural contexts, such as their country-specific economic development needs, in the teaching and learning. Yet, the pedagogic approaches involved in these programmes follow internationally recognised educational methods where English, an international language, is used as the medium of instruction. The Pathways programme primarily focuses on developing students’ English-language skills in an approach that equips them with linguistic and communicative competencies, enabling them to become effective communicators in both academic and social environments. The students go through a competency-based learning approach in which language is treated as a medium of interaction and communication among people from different cultures aiming to achieve common goals and purposes. This helps them fulfil the expectations of any international curricula which are to develop cross-cultural and intercultural awareness (Clifford & Montgomery, 2017). Another important aim is to develop students’ teamwork and leadership skills. These behavioural competencies are achieved through core curricular and extracurricular activities, such as project work and community engagement. Enabling students to take responsibility for their own learning is also an integral aspect. So far, the outcomes of the programme have been very encouraging as the students have demonstrated excellent perseverance to work for their own and for the betterment of their home countries.

The Access Academy is contributing with great novelty by recruiting female students from several fragile and conflict-affected countries where female education has become virtually elusive. For example, through an agreement between AUW and Daughters for Life Foundation (http://daughtersforlife.com), many disadvantaged young women from the Middle East have received scholarships for undergraduate education. AUW and the Daughters for Life Foundation have supported vulnerable students from Palestine and Syria in tuition waivers and awards to cover all costs of their undergraduate studies including learning at the Access Academy. Besides, the university has successfully mobilised international collaboration with Afghanistan, a country where most systematic and destructive abuses against women have been executed through the denial of education. In recent years, more than 100 students from various disadvantaged and ethnic groups in Afghanistan have been recruited. These women, who once feared to even dream, now actually stand with their heads held high.

With the unique educational interventions by Pathways for Promise and Access Academy programmes, AUW has been reaching more students in Asia and the Middle East (in 2019, there were enrolments from Yemen and Senegal for the first time). The university has graduated over 700 exceptional young women to become leaders in their communities. Ninety percent of them have received employment or enrolled in higher education programmes within one year of their graduation. Among the employed graduates, around 85% work in their home countries. Twenty five per cent of graduates are enrolled in further studies, with some completing programmes at world-renowned higher educational institutions, such as Stanford, Columbia, Johns Hopkins, Oxford, Edinburgh, and Yonsei. In addition to the academic support from Pathways for Promise and Access Academy, the students have also been benefited from the AUW’s extensive international networks with educational institutions, industries, and employers. These links have eventually helped them obtain places in internship and study abroad programmes, and in securing employments internationally. At the same time, AUW has been able to develop its curriculum and engage many visiting faculty members, resulting in a stronger academic profile and achievements.

The performativity and impacts of a university are reflected through the way its academic programmes are devised and delivered. The curriculum of the Pathways for Promise and Access Academy programmes at the Asian University for Women demonstrates strengths of rigorous academic coaching to optimise potentials of exceptional and struggling students. One of the challenges in such an educational approach is fostering curiosity and confidence among the students to deal with different social, cultural, and religious views (Cameron, 2019). It is also plausible that the students face challenges while practising critical thinking and communication from multicultural viewpoints. Yet, this type of bridging or preparatory programmes facilitate “borderless, capitalist, civic, collaborative, cosmopolitan, disciplinary, marketised” characters which are the defining elements of modern higher education curricula (Barnett, 2013, p. 51). Moreover, the value of such programmes is widespread as the students’ learning gains are developed through and connected with real world circumstances.

Creating Cross-cultural Learning Space

A very small number of university students get a chance to study abroad, and the number is much lower in developing countries (de Wit, Gacel-Avila, Jones, & Jooste, 2017). However, the blessings of modern technology offer the provision for being connected with international academic stakeholders and share cross-cultural views while studying in the home country. This kind of knowledge sharing is essential in some academic disciplines; for example, business students need to understand consumer behaviours, marketing cultures, and business policies in different places. Technology-enabled and internationally connected curricula can help them attain useful competencies to become engaged in diverse cultural, economic, and political perspectives.

Research findings show higher student motivation and participation in international academic programmes (Trinh & Conner, 2019). However, we know very little about how students engage and behave in similar programmes when they are based in the home countries, and the teaching and learning are conducted using technology. Research findings on technology-enhanced learning provide indications of several challenges, for example gaps between technological designs and pedagogic actions (Davey, Elliott, & Bora, 2019), and participants’ lack of understanding of the cultural and intellectual backgrounds of their peers (Jamil, 2018). On the contrary, there is ample evidence of successful learning delivered by technology-enhanced activities, for example improved self-awareness and reflective practice through blogging (Barrett, Hayes, & Hollinshead, 2019), and rich academic discussion through Facebook-generated tasks (Manca & Ranieri, 2013). The next case study describes how an online classroom enables positive learning experiences for students studying in their home countries in Europe and Asia.

Case Study 2

Collaborative online international learning (Natascha Radclyffe-Thomas, Professor of Marketing and Sustainable Business at the British School of Fashion, Glasgow Caledonian University, UK)

Collaborative online international learning (COIL) is an award-winning project launched in 2013 to deliver authentic education through formal and informal collaboration between higher educational institutions in the UK and Asia. The International Fashion Panel (IFP), a global classroom in the form of a private Facebook group and part of the COIL project, has been facilitating collaborative work practices between students at four universities studying in areas of fashion design, business, marketing, media and communications. Students in the IFP are undergraduates, and the global classroom provides blended learning integrated into specific modules, for example, Fashion Branding or Media Communications. The initial partner institutions were the London College of Fashion and City University Hong Kong. Subsequently, the collaboration has extended to LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore, and RMIT’s satellite campus in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Developed to support internationalisation in its widest sense, the IFP had the following motivations behind its formation:

-

1.

to facilitate international research in the area of fashion branding and marketing

-

2.

to support a peer network in order that students recognise not just others’ but also their own social and cultural capital

-

3.

to stimulate cultural exchange and promote intercultural communication competences

-

4.

to introduce internationally situated project briefs focusing on non-homogenous markets

-

5.

to support international students, especially those with English as a second/foreign language, in group work and class discussions

-

6.

to simulate industry work practices with peer collaboration via asynchronous and digitally enabled communication

The IFP is primarily being used in the first year of studies. The teaching teams at each partner institution have conducted curriculum-mapping exercises which help them identify synergies in modules across content and assessment design. The students have been introduced to the global classroom, with an emphasis on its functions and benefits as a platform for collaborative research, in project briefings. Due to the global nature of the creative industries, and the risks of cultural appropriation and/or cross-cultural communication crises, an agreement has been established among institutions regarding the necessity of examining the local-global nexus, and how it manifests in products and marketing communications.

The name ‘International Fashion Panel’ was chosen to minimise real and perceived teacher-student hierarchies and the cultural distance between home and international students. The programme encourages students to recognise and develop their own expertise and the value of their knowledge and opinions. The objectives are achieved through a series of introductory activities designed to foster a community of learners and to demonstrate the shared interests and references between peer learners in each location—an example being asking students to create a post stating three companies they want to work for and three places they would like to live. Most students are familiar with presenting themselves via social media platforms; thus the exercise was fairly low-risk and they could reveal information as much or little as they wished. The activity highlighted the global nature of the fashion industry and offered students a chance to situate their (geographic) place within that. By sharing aspirations, they discovered the shared interests and preferences denoting a community of practice. It also served to foreground internationalisation in a positive way through recognising students’ diverse backgrounds as they discussed each other’s posts. In a similar manner, the positive integration of a non-homogenous and international lens on the practice of marketing communications was further integrated by a brand identity activity which uses a series of tutor-created brand mood boards representing a range of international fashion brands. Students were asked to discuss their interpretations and post comments on the perceptions of each brand’s identity and strategy using the 4Ps framework (product-place-price-promotion). The activity served to familiarise them with the global classroom format before moving into deeper engagement in the form of peer collaboration and review. The examples of such activities include cross-cultural seminar discussions and debates. Having posted a question such as ‘to what extent do you think there is global fashion?’ tutors facilitated in-class small group discussions, the summaries of which were captured as comments on the tutors’ original post. As the course in London has a large cohort, the global classroom has run several concurrent seminars and provided students an opportunity to contribute to a live cross-campus conversation. Students in the partner colleges have joined the discussion sessions or used the results to prompt their own, although these have been conducted asynchronously due to the time difference.

Graduates who aspire to work in the creative industries are increasingly required to work in virtual teams, often with culturally diverse colleagues. Additionally, the strategy and content they create are required to reflect the international nature of contemporary industry. Most approaches to internationalisation of curriculum attempt to expose students to alternate cultural artefacts and practices. While designing separate but aligned project briefs that explicitly reference the global classroom as a source of primary research, tutors of such curricular methodology require students to propose internationally viable strategies for selected fashion brands. To address this need, recent project briefs of the global classroom have asked students in Hong Kong to select a local Chinese brand to launch in London. Students in London were given an Asian city to research and either bring a local brand to London or launch a British brand there. To help students do useful research prior to seminars, global classroom tutors posted relevant articles and sources for further information.

The International Fashion Panel has so far connected over 750 students, tutors, and industry experts in exploring common interests and co-creating knowledge. Experiences of the students have been studied through exploratory investigations using questionnaires, focus groups, students’ reflective writing, as well as analyses of the group’s metrics and tutors’ observations. The findings indicate positive outcomes, particularly in facilitating geographically dispersed individuals to connect, share, and create content and ideas. The global classroom is only one aspect of the teaching delivery, but its ability to research and sense-check with peers living in the target markets has emerged as an invaluable source of qualitative data and feedback which ultimately enhance students’ work. Students have been found supporting their peers by preparing local fashion intelligence reports and providing feedback on work in progress. Overall, based on a model of communities of practice, it has created a successful network of learners for whom the classroom has been extended beyond the walls of their institutions, and their social and cultural capital has been enhanced and recognised. The following comment of a participant represents positive impacts of the IFP and the global classroom:

It’s like being a part of this creative learning community and people from different cultural backgrounds coming together to talk about the same topic. … it helped understand the perspective of people from the countries we based our project on. I also learnt so much about what people from other countries thought about my own culture. It was a very helpful learning experience. (London-based student)

(A detailed description of the collaborative online international learning project is available in Radclyffe-Thomas, Peirson-Smith, Roncha, Lacouture, and Huang, 2018).

The IFP and global classroom are an international and technology-enhanced curriculum environment which addresses two major educational challenges. First, many students and faculty members often fail to recognise the purposes and goals of international programmes (Green & Whitsed, 2015); therefore the global classroom provides appropriate briefings to its students on the procedures and benefits of their participation. Second, managing learning experiences of diverse student cohorts based in different countries is problematic (Irvine, Molyneux, & Gillman, 2015), so the global classroom sets small and controlled activities in the beginning to prepare students to partake in deeper and more complex tasks in later stages. The collaborative and dialogic nature of the learning activities, and the profession-focused content, also help them become part of wider communities of practice (Wenger, 1998). Overall, the virtual learning environment creates a cross-cultural space enabling self-reflection and openness to other cultures, and curiosity about non-homogenous industries situated in different geographic locations.

Linking Contexts with Inquiry and Analysis

International curricula demand contextual multiplicity in the learning and teaching. The requirement is compatible with emerging real world learning concepts which have a primary focus on the continuation and application of learning beyond formal education. Embedding inquiry and ‘linking knowledge to action’ in education can facilitate continuing and applied features (Brundiers et al., 2010). They can also supply pedagogic options for collaboration and deep learning, and equip students with utilisable lifelong skills (Tong, Standen, & Sotiriou, 2018). However, the success of inquiry-based education depends on students’ prior knowledge and cultural capital in the forms of critical thinking, interdisciplinary knowledge, and communication skills. Besides, many students struggle with dissimilar educational approaches, for example collaboration and questioning, especially if they are contradictory and different from their previous learning experiences (Rienties, Nanclares, Jindal-Snape, & Alcott, 2013). Consequently, some students find the learning experiences unconventional, inconsistent, and time and resource demanding (Bak & Kim, 2015). It is plausible that many students cannot participate equally and struggle academically in international academic programmes which involve culturally variant stakeholders and unique learning goals.

Inquiry-based learning is an intellectually stimulating academic approach which has recently gained ground in contemporary higher education. The approach has potentials to connect research and employment skills in education, and help students embrace twenty-first-century workplace challenges through innovative and creative measures (Acar & Tuncdogan, 2019; Campbell & Groundwater-Smith, 2013). The following case study, taken from BRAC University in Bangladesh, shows a developmental approach to strengthen traditional curriculum for supporting students to participate in inquiry-based learning with enhanced awareness of global perspectives and future professions.

Case Study 3

Outcome-based programme design (Mohammad Aminul Islam, Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Languages, BRAC University, Bangladesh, and Annajiat Alim Rasel, Undergraduate Programme Coordinator at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, BRAC University, Bangladesh)

BRAC University in Bangladesh follows broad-based or holistic approaches to learning and teaching. Since 2007, its academic programmes have been receiving outcome-based educational interventions on a regular basis to improve students’ awareness of global perspectives. In addition to continuous quality improvement, in 2016, the university placed an emphasis on General Education (GenEd). Consequently, since 2018, Outcome-Based Education (OBE) has become a key driver of the university’s overall curriculum. While implementing these programmes, the university took measures to ensure that the taught courses are academically relevant and globally competitive. As part of the process, the design of each academic course starts with a broad and general curriculum framework emphasising communication, critical thinking, quantitative skills, technological skills, and global thinking skills. All these components are interlinked in such a way that the students can align their learning with various real-life international challenges, starting from the orientation of a topic to the assessment of learning through concept-building activities. The curriculum has been further developed through recommendations from various accreditation bodies, resulting in a clearer focus on mapping its every component in granular details, from Programme Educational Objectives (PEO), Programme Learning Outcomes (PLO), down to Course Learning Outcomes (CLO), and how they are addressed in each learning and assessment activity. The curriculum and faculty members have been prepared with the help of BRAC University’s Institutional Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) and Professional Development Centre (PDC). PDC offers courses like Theory and Practice of Learner-centred Teaching (TPLT). TPLT is a professional development programme for BRAC University faculty members which includes teaching-learning methods, feedback rubric, technology-enhanced learning, collaboration, inquiry, practice, and production of articulations.

The text and reference materials as well as the ‘project challenges’ used in the taught units for the students are brought directly from international examples. For instance, books are chosen such that they are written by persons who are considered to have contemporary authority on the subjects, and the contents are complemented with authentic examples chosen from international locations. In ‘project challenge’ tasks, students are asked to analyse their proposed solutions in terms of different time zones and cultural variations (including values, languages, and preferences). As books tend to get outdated relatively quickly, students are encouraged to interact with professionals for exposure of fresh perspectives and industry challenges, and mimic what they would be doing in their job or during postgraduate education.

To instil research and development practices in the learning, students are introduced to challenges and are assessed on how their solutions take global contexts into account. The tasks are facilitated in collaborative, interactive, and sometimes flipped environment where the role of the instructors is mainly as facilitators and co-learners. Students are challenged with worklets based on professions or postgraduate life preceded by bridge materials. This helps them make a smooth connection between the topics covered with some anticipated profession-related challenges that they may face in future. The teaching also uses evidence-driven and interactive peer-instruction method (Mazur & Somers, 1999). Classes generally start with a review of past topic, content for the day along with pre-assessment and post-assessment, and a preview of upcoming topics. In the case of a course involving communication skills, global awareness is emphasised using examples like ‘thumbs up’, which is a positive feedback in many cultures, but the same gesture is treated very negatively in the cultures of some Asian countries. In courses having technical components, students are made aware of different languages and colours, accessibility issues for users with disabilities, scalability of solutions, robustness, and account for the increasing global security concerns, such as data leaks and data breaches. Students are exposed to a wide range of tools and resources, such as VuFind for knowledge discovery, Moodle LMS, KJS ThinkBoard (a Japan International Cooperation Agency pilot project for e-learning in Bangladesh), Mentimeter, and various simulation tools in their learning. Additionally, they deal with technical instruments and frameworks which are applied in relevant industries. Students also attend tutorial sessions where they can discuss academic confusions and receive further challenging tasks.

While accomplishing the coursework, students are required to interact with professionals and academics on global forums, such as Stack Overflow, Stack Exchange, Quora, newsgroups, Facebook/Google groups, Piazza, and MOOC platforms. They are made familiar with examples of what they may expect in their jobs or postgraduate studies at local or international institutions. They are also exposed to strategic thinking on how to handle unseen, complex, and hard-to-tackle problems, trade-offs and compromises, the importance of looking at the same problem from different angles, breaking down a problem into sub-problems, and collaborative approaches to problem solving. The course contents include various local and international compliance issues, for example international industrial certifications and international competitions. As academic disciplines are often different in terms of their learning goals and teaching approaches (Shulman, 2005), the nature, content, and features of these courses vary in different academic disciplines. Besides, regular modification and adjustment take place for all the courses in every semester to stay relevant to the needs of the future, to improve student engagement, and to support their sustainable active learning.

Outcome-based academic interventions at BRAC University have delivered some significant success. The students are receiving internship, industrial mentorship, and job offers from local and international organisations. Many have joined research-based programmes just after completing their degrees. Many batches of the students have initiated their own start-up companies. Students are regularly participating in national and international competitions and winning prizes. The academic changes and their outcomes have already contributed to boosting the ranking of BRAC University.

Internationalisation of academic programmes prioritises cross-cultural competencies and intercultural awareness (Knight, 2013). Enabling inquiry and analysis in global-facing programmes requires students’ cultural and academic readiness. Faculty members’ positive attitudes and perceptions towards internationalisation are also pivotal in the process (Childress, 2010). BRAC University’s outcome-based curriculum development initiative demonstrates a structured approach to embedding inquiry and analysis in international academic programmes. Yet, it is plausible that students’ capacities to partake in such educational environment vary because they bring different types and levels of learning cultures and critical thinking abilities in the class.

In higher education literature, various guidelines regarding effective teaching and student participation in inquiry-based learning are available (Coffman, 2017; Mieg, 2019; Pedaste et al., 2015). However, discussions on how these approaches are relevant and linked to student learning in international academic programmes and life-long learning contexts are inadequate; thus it requires further exploration. It is also important to gauge the roles and impacts of academic and social support in students’ learning journeys.

Conclusions

The discussion in this chapter sheds light on some pertinent curricular features delineating real world learning in internationalised academic programmes. Real world learning emerges as a context-rich and applied educational approach having potentials to enable engagement, critical thinking, cooperation, and knowledge transfer beyond formal educational settings. The main objective of the approach is to transform students into global citizens who are ready to learn through cross-cultural exploration and collaboration, and are equipped with essential competencies to apply learning to real-life actions. The external-facing educational environment is a key driver in the internationalisation process and real world learning pedagogies, although both encourage students to apply critical thinking and analysis in understanding their own cultures too.

The notions and practical examples detailed in the three case studies signpost effective approaches to designing and implementing authentic learning activities in international academic programmes. The discussion provides at least three guiding principles: (1) inclusion of wider communities and their views as well as academic and professional needs in the teaching and learning practice, (2) creating opportunities to expand collaboration and communication across geographic borders, and (3) amalgamation of local and global views in learning activities, such as inquiry, reflection, and analysis. Philosophically, all these elements can supply opportunities to practise real world learning with enhanced global thinking skills, but it is likely that they may not always lead to high student satisfaction. One of the reasons is that many students face difficulties while studying in international learning environments as they go through distinct cultural adaptation and academic assimilation processes. Therefore, the quality and quantity of students’ learning gain may exceptionally vary in international academic programmes. This may also pose a challenge for faculty members, particularly in managing disparate levels of student achievement and satisfaction. To overcome the problems, the case studies, along with the learning and teaching concepts, suggest some curricular strategies, such as delivering preparatory academic programmes to enhance students’ communication skills and cultural awareness; providing exposures of international social, economic, and political events to enhance students’ motivation and engagement; and using modern technology to reach diverse people and cultures situated in different geographic locations. It is possible that these suggested actions will face resistance, or they may require to include alternative curricular strategies for successful teaching and learning in specific higher educational institutions. However, the discussed real world learning concepts and the real examples can be a starting point to explore evidence-based and sustainable academic approaches suitable for the internationalisation of higher education.

References

Acar, O. A., & Tuncdogan, A. (2019). Using the inquiry-based learning approach to enhance student innovativeness: A conceptual model. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(7), 895–909. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1516636

Asian University for Women (AUW). (n.d.). History. Retrieved May 5, 2019, from https://asian-university.org/who-we-are/history/.

Bak, H., & Kim, D. H. (2015). Too much emphasis on research? An empirical examination of the relationship between research and teaching in multitasking environments. Research in Higher Education, 56(8), 843–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9372-0

Barnett, R. (2013). Imagining the university. London: Routledge.

Barrett, G. A., Hayes, A., & Hollinshead, J. (2019). Study abroad and developing reflective research practice through blogs: A preliminary study from the United Kingdom. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 30, 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2019.1580757

Barua, J. B. (2016). Ancient Buddhist universities in Indian sub-continent. Meadville: Fulton Books.

Boss, S. (2015). Real-world projects: How do I design relevant and engaging learning experiences. Alexandria: ASCD.

Brundiers, K., Wiek, A., & Redman, C. L. (2010). Real-world learning opportunities in sustainability: From classroom into the real world. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 11(4), 308–324.

Cameron, A. (2019). Cultural and religious barriers to learning science in South Africa. In B. Billingsley, K. Chappell, & M. J. Reiss (Eds.), Science and religion in education (pp. 189–202). Cham. Retrieved from: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-17234-3_15

Campbell, A., & Groundwater-Smith, S. (Eds.). (2013). Connecting inquiry and professional learning in education: International perspectives and practical solutions. London: Routledge.

Childress, L. K. (2010). The twenty-first century university: Developing faculty engagement in internationalization (Vol. 32). New York: Peter Lang.

Clifford, V., & Montgomery, C. (2015). Transformative learning through internationalization of the curriculum in higher education. Journal of Transformative Education, 13(1), 46–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344614560909

Clifford, V., & Montgomery, C. (2017). Designing an internationalised curriculum for higher education: Embracing the local and the global citizen. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(6), 1138–1151. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1296413

Coffman, T. (2017). Inquiry-based learning: Designing instruction to promote higher level thinking. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

Davey, B., Elliott, K., & Bora, M. (2019). Negotiating pedagogical challenges in the shift from face-to-face to fully online learning: A case study of collaborative design solutions by learning designers and subject matter experts. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 16(1), 3.

Egron-Polak, E., & Hudson, R. (2014). Internationalization of higher education: Growing expectations, essential values. IAU 4rd Global Survey Report. Paris: IAU.

Green, W., & Whitsed, C. (Eds.). (2015). Critical perspectives on internationalising the curriculum in disciplines: Reflective narrative accounts from business, education and health (Vol. 28). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Irvine, J., Molyneux, J., & Gillman, M. (2015). ‘Providing a link with the real world’: Learning from the student experience of service user and carer involvement in social work education. Social Work Education, 34(2), 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2014.957178

Jahangir, A. (2016, November 4). The Workers’ Revolution. The Daily Star. Retrieved November 25, 2019, from https://www.thedailystar.net/star-weekend/spotlight/the-workers-revolution-1308979

Jamil, M. G. (2018). Technology-enhanced teacher development in rural Bangladesh: A critical realist evaluation of the context. Evaluation and Program Planning, 69, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.04.002

Jibeen, T., & Khan, M. A. (2015). Internationalization of higher education: Potential benefits and costs. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 4(4), 196–199.

Knight, J. (2013). The changing landscape of higher education internationalisation–for better or worse? Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 17(3), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2012.753957

Leask, B. (2015). Internationalizing the curriculum. London: Routledge.

Manca, S., & Ranieri, M. (2013). Is it a tool suitable for learning? A critical review of the literature on Facebook as a technology-enhanced learning environment. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29(6), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12007

Mann, H. (1957). The Republic and the School: Horace Mann on the Education of Free Men. 12th Annual Report to the Massachusetts Board of Education–1848. New York: Teacher’s College, Columbia University.

Marriott, P., Tan, S. M., & Marriott, N. (2015). Experiential learning—A case study of the use of computerised stock market trading simulation in finance education. Accounting Education, 24(6), 480–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2015.1072728

Maxwell, M., Stobaugh, R., & Tassell, J. L. (2015). Real-world learning framework for secondary schools: Digital tools and practical strategies for successful implementation. Bloomington: Solutions Tree Press.

Mazur, E., & Somers, M. D. (1999). Book reviews-peer instruction: A user’s manual. American Journal of Physics, 67(4), 359–359.

Mieg, H. A. (2019). Inquiry-based learning–undergraduate research. Berlin: Springer. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14223-0

OECD. (2004). Internationalisation and trade in higher education: Opportunities and challenges. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264015067-en

Otterspeer, W. (2008). The bastion of liberty: Leiden University today and yesterday. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

Ovenden-Hope, T., & Blandford, S. (2017). Understanding applied learning: Developing effective practice to support all learners. London: Routledge.

Pedaste, M., Maeots, M., Siiman, L. A., De Jong, T., Van Riesen, S. A., Kamp, E. T., … Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review, 14, 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003

Pinkney, A. M. (2015). Looking west to India: Asian education, intra-Asian renaissance, and the Nalanda revival. Modern Asian Studies, 49(1), 111–149. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X13000310

Radclyffe-Thomas, N., Peirson-Smith, A., Roncha, A., Lacouture, A., & Huang, A. (2018). Developing global citizenship: Co-creating employability attributes in an international community of practice. In D. Morley (Ed.), Enhancing employability in higher education through work based learning (pp. 255–275). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75166-5_14

Rau, K., Griffith, R. L., & Dieguez, T. A. (2019). Out of the classroom and into the deep end: Real world learning at ICCM. In M. A. Gonzalez-Perez, K. Linded, & V. Taras (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of learning and teaching international business and management (pp. 159–184). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20415-0

Rienties, B., Nanclares, N. H., Jindal-Snape, D., & Alcott, P. (2013). The role of cultural background and team divisions in developing social learning relations in the classroom. Journal of Studies in International Education, 17(4), 332–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315312463826

Sharma, S., Charity, I., Robson, A., & Lillystone, S. (2018). How do students conceptualise a “real world” learning environment: An empirical study of a financial trading room? The International Journal of Management Education, 16(3), 541–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2017.09.001

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1162/0011526054622015

Tong, V. C., Standen, A., & Sotiriou, M. (Eds.). (2018). Shaping higher education with students: Ways to connect research and teaching. London: UCL Press.

Trinh, A. N., & Conner, L. (2019). Student engagement in internationalization of the curriculum: Vietnamese domestic students’ perspectives. Journal of Studies in International Education, 23(1), 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318814065

Vishwanath, T. P., & Mummery, J. (2019). Reflecting critically on the critical disposition within internationalisation of the curriculum (IoC): The developmental journey of a curriculum design team. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(2), 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1515181

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

de Wit, H., Gacel-Avila, J., Jones, E., & Jooste, N. (Eds.). (2017). The globalization of internationalization: Emerging voices and perspectives. London: Taylor & Francis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jamil, M.G., Alam, N., Radclyffe-Thomas, N., Islam, M.A., Moniruzzaman Mollah, A.K.M., Rasel, A.A. (2021). Real World Learning and the Internationalisation of Higher Education: Approaches to Making Learning Real for Global Communities. In: Morley, D.A., Jamil, M.G. (eds) Applied Pedagogies for Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46951-1_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46951-1_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-46950-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-46951-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)