Abstract

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is a prime example of a systems disease. In the initial phase, apolipoprotein B-containing cholesterol-rich lipoproteins deposit excess cholesterol in macrophage-like cells that subsequently develop into foam cells. A multitude of systemic as well as environmental factors are involved in further progression of atherosclerotic plaque formation. In recent years, both oral and gut microbiota have been proposed to play an important role in the process at different stages. Particularly bacteria from the oral cavity may easily reach the circulation and cause low-grade inflammation, a recognized risk factor for ASCVD. Gut-derived microbiota on the other hand can influence host metabolism on various levels. Next to translocation across the intestinal wall, these prokaryotes produce a great number of specific metabolites such as trimethylamine and short-chain fatty acids but can also metabolize endogenously formed bile acids and convert these into metabolites that may influence signal transduction pathways. In this overview, we critically discuss the novel developments in this rapidly emerging research field.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD), including coronary heart disease and stroke, are still the main causes of death in the Western world. In the last decades, extensive research programs have attempted to unravel molecular mechanisms underlying these debilitating diseases. Substantial progress has been made particularly in identification of the causal role of low-density lipoprotein (Ference et al. 2017) and triglyceride-rich remnants (Nordestgaard 2016). Although the focal point in research is often directed to cholesterol-containing lipoproteins, the major predictive risk factor for ASCVD is age (Pencina et al. 2019). The vascular aging process that underlies ASCVD risk is a complex process in which lipoproteins and blood pressure interact with the vessel wall and a number of environmental factors exert a secondary influence. One of these factors, which has gained substantial interest in recent years, is the microbiome defined as all microorganisms that colonize the body. Although the vast majority of microbiome studies concentrate on the gut, the oral microbiome may play a significant role in the context of ASCVD development. In this overview, we will critically review recent literature that focuses on the role of the microbiome in ASCVD.

ASCVD is a prime example of a systems disease. The obligate substrate is deposition of cholesterol in the vessel wall. Once depot formation is initiated in the form of foam cells, a host of additional factors such as inflammatory processes further determine disease progression through a plethora of actions. Note that inflammatory processes may also control lipid levels in the blood, thereby exerting control on multiple steps in development of atherosclerosis. Until recently, most of the information about the importance of inflammation in ASCVD came from studies in animal models. The results of the CANTOS trial, which showed a beneficial effect on ASCVD events through antibody-mediated inhibition of interleukin-1β, have added critical insight in the role of inflammation in ASCVD development in humans (Ridker et al. 2017). Inflammation is an extremely complex process by itself, and it is therefore not surprising that novel inflammation-modulating factors pop up continuously as potential ASCVD influencers. Yet, the onset of the disease requires lipid disposition mediated primarily by apolipoprotein B (apoB)-containing lipoproteins. The dominant role of these lipoproteins was nicely exemplified by Mendelian randomization studies that make use of natural mutations in the genes encoding lipoproteins (reviewed in Holmes et al. 2017). This enabled studies into the effect of variations in circulating cholesterol carriers on ASCVD risk (Ference et al. 2017). In addition, LDL-C lowering trials using statins with or without ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors have provided critical insight in the role of cholesterol carriers and ASCVD risk (Wright and Murphy 2016). Interestingly, there is linear relation between LDL-C levels and cardiovascular events in which zero disease risk was associated with circulating LDL-C levels of around 1 mM (Wright and Murphy 2016). This suggests that at this level, the risk of cardiovascular events is close to zero and no disposition of lipid in the vessel wall will occur. In the general population, however, the concentration of apoB-containing lipoproteins is much higher than 1 mM, and some degree of atherosclerotic plaques development is almost inevitable. Indeed in the 1960s of the last century, studies in young soldiers that died in the Korean and Vietnam wars demonstrated early signs of atherosclerotic plaque formation as early as 25 years of age in about 5% of the soldiers (Virmani et al. 1987). Fortunately, certainly at ages lower than 60 years, most atherosclerotic plaques are not symptomatic. A majority of current research initiatives therefore focuses on processes that induce vulnerability of the plaque to rupture, one of the main causes for acute coronary syndromes.

In short, lipid deposition in the vessel wall and complex inflammatory processes are critical for development of ASCVD. In addition, aging and environmental factors such as smoking and diet play an important role herein. More recently, both oral and gut microbiome have entered the spotlights. Before considering the role of the microbiome in ASCVD development in detail, we will first give an update on recent oral and gut microbiome literature and focus on host-microbiome interactions relevant for progression of ASCVD.

2 Gut and Oral Microbiome Communities: Potential Drivers of ASCVD?

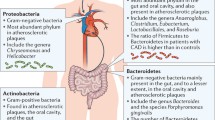

The gut and oral microbiome are the first and second, respectively, largest and most complex communities of microorganisms in the human body and comprise bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea, and protozoa. It is critical to point out that the vast majority of publications on the role of the gut and oral microbiome in human health and disease are heavily biased toward bacterial members of this community. The upcoming awareness of the critical role of other members of the microbiome to composition and function of the community – and thereby contribution to human metabolism – is likely to change this bias in the coming decade. We will first elaborate on the bacterial component of the (gut and oral) microbiome and their postulated role in ASCVD development. Mechanistically, both the gut and oral microbiome are currently considered to affect human metabolism and ASCVD by interaction with the host immune system (gut and oral) and by conversion of dietary components into hormone-like signals or biologically active metabolites (gut) (Fig. 1).

Oral and gut microbiome have been implicated in the development of ASCVD (a). Increased pathogen abundance in the oral cavity, such as during periodontal disease, might reach the circulation and contribute to low-grade inflammation, a recognized risk factor for ASCVD. In addition, continuous swallowing of bacteria from the oral cavity has been suggested to alter gut microbiome composition, thereby contributing to ASCVD development (b). Please see text for details

The gut microbiome (estimated number of species >1,000, 1.5–2 kg per person) is a critical component of digestion, maintenance of gut barrier function, and immunomodulation. The predominant bacterial phyla are Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, with Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia being less abundant (Shetty et al. 2017). Methanogens are dominant among the archaea (Paterson et al. 2017). The vast majority of gut bacteria are shared among individuals at higher taxonomic levels (phylum). However, interindividual variation at lower taxonomic levels (species, strain) is very high. Alterations at this level, in particular reduced number and diversity of bacterial genes, have been associated with metabolic diseases including ASCVD (reviewed in Aron-Wisnewsky and Clément 2016; Liu et al. 2019; Tilg et al. 2019).

ASCVD risk factors have been reported to associate with the gut microbiome; for example, Clostridiales and Clostridium spp. correlate negatively with C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker (Karlsson et al. 2012). The gut microbiome of ASCVD patients has been associated with decreased abundance of gut commensals such as Bacteroidetes (incl. Bacteroides and Prevotella) compared to healthy controls (Emoto et al. 2016). A metagenome-wide association study (Jie et al. 2017) in fecal samples of ASCVD patients and healthy controls reproduced findings on the reduced abundance of Bacteroidetes in ASCVD patients and further reported that these patients had reduced abundance of presumably beneficial short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria such as Roseburia intestinalis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Conversely, the microbiome of ASCVD patients was enriched in species belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family, which are oftentimes associated with gut microbiome dysbiosis and (metabolic) disease development. Interestingly, the relative abundance of bacteria typical for the oral cavity, in particular Streptococcus spp., was also higher in the gut microbiome of patients with ACVD compared to healthy controls.

With over 700 bacterial species, the oral cavity comprises the second largest and most diverse microbiome community after the gut in the human body. These species are located in a plethora of very complex niches including the hard surfaces of the teeth as well as the soft mucus linings of the mouth. The mouth is the major entrance point to the human body. Bacteria from the oral cavity, in particular those associated with oral infectious diseases and adapted to thrive in an inflammatory environment (e.g., caries (tooth decay) and periodontitis (gum disease)), have been associated with “off-site” effects on systemic diseases such as ASCVD (Hajishengallis 2015).

Although the number of studies that have associated differences in gut and oral microbiome composition with ASCVD is plentiful, it is important to point out that data on a causal role for the gut microbiome in ASCVD development in humans is more difficult to find. The strongest evidence for a causal role of the gut or oral microbiome in progression of ASCVD has been derived from animal studies, in particular mouse models (Table 1). Germ-free (sterile) apolipoprotein E-null (ApoE −/−) mice were shown to have increased atherosclerotic plaques compared to conventionally raised counterparts when fed a chow diet (Stepankova et al. 2010). These data were confirmed by Lindskog et al. but only with respect to the chow diet (Jonsson et al. 2018). Conversely, when germ-free ApoE −/− mice were fed a high-fat/high-cholesterol diet, the absence of microbiota increased atherogenesis, but the extent was still reduced compared to conventionally raised mice (Jonsson et al. 2018). However, there is some controversy around these data because Kasahara et al. reported decreased atherosclerosis in germ-free ApoE −/− mice on a chow diet (Kasahara et al. 2017). Since chow diets are not well characterized and composition differs from batch to batch, the apparent discrepancy may well be caused by subtle changes in the diet used in the different studies.

Convincing data for a causal role of the microbiota in ASCVD development came from fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) studies showing that atherosclerosis was induced when FMT was carried out with feces derived from mice with proven atherosclerosis (Gregory et al. 2015). The question arises which factor is responsible for the atherosclerosis aggravating effect induced by the microbiome. Activation of inflammatory signaling pathways by the gut microbiome, or components thereof, has received a lot of attention in the past decade. This is exemplified by observations that transplantation of a pro-inflammatory microbiome into atherosclerosis-prone LDLR−/− mice accelerated phenotype development compared to LDLR−/− mice receiving a control microbiome (Brandsma et al. 2019). Translocation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) across the intestinal wall into the blood seems a good mechanistic candidate. LPS is the major molecular component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, the most abundant bacteria in the gut (Raetz and Whitfield 2008). The lipid A component of LPS is a pathogen-associated molecular pattern, which activates Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (Aderem and Underhill 1999). High-fat diet has been shown to increase gut permeability in mice. This may enhance the translocation of LPS into the circulation thereby inducing metabolic endotoxemia (Cani et al. 2007). In line, germ-free mice were demonstrated to be resistant to high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and obesity (Rabot et al. 2010). Whether these results in mice can be translated to humans remains to be established.

Identification of atherosclerotic plaque-associated bacteria is suggestive of a direct role in plaque progression (Koren et al. 2011; Jonsson et al. 2017). Interestingly, many of these bacteria were also localized in the oral microbiome of patients with atherosclerosis. Indeed, a close association between periodontitis and ASCVD risk has been reported in a number of studies (Hajishengallis 2015). Gingival bleeding caused by periodontitis offers oral bacteria an easy entry into the circulation where they can attach to the atherosclerotic plaque. Whether they stay alive when bound to the plaque is not clear. As far as we are aware, no live bacteria have been cultured from plaques obtained during surgery. Yet, upon entry into the blood, the orally derived bacteria may be capable of activating endothelial cells, possibly leading to expression and secretion of metalloproteinases that in turn may decrease plaque stability. The activity of periodontitis has been shown to be reflected in systemic inflammation. This is important given the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of ASCVD. Plasma levels of the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein (CRP) have been correlated with periodontitis status (Noack et al. 2005; Yoshii et al. 2009) as well as the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 (Loos et al. 2005). These immune modulators may be either produced locally in the oral environment and subsequently secreted into the circulation or arise as a result of low-grade, short-lived bacteremia (Torres De Heens et al. 2010). Given the high prevalence of periodontitis in the adult population, treatment of this disease may be an important modality to reduce the incidence of ASCVD (Lobo et al. 2019).

Summarizing these studies, it seems fair to conclude that activation of an inflammatory pathway is a reasonable way via which bacteria may promote progression of ASCVD. Whether the prokaryotes that enter the circulation via the oral cavity or gut play a role in affecting plaque stability has not yet been shown. In a study in mice, Jonsson et al. (2017) did not find differences in bacterial content between stable and labile plaques. However, activation of the inflammatory component of ASCVD may not be the only way by means of which the microbiota exert influence.

2.1 Other Microbiome Community Members

Although bacteria and archaea indeed account for >99% of microbiome mass (Shkoporov and Hill 2019), it should be realized, however, that both the oral and gut microbiome contain vast numbers of viruses, fungi, and – in most humans – protozoans. Although many of these less abundant community members have been linked to human disease (Hoffmann et al. 2013; Huseyin et al. 2017; Paterson et al. 2017; Laforest-Lapointe and Arrieta 2018), surprisingly little is known about trans-kingdom community-level interactions and the consequences thereof for human health. In order to deepen our understanding about the complexity of host-microbial interactions, it will be critical to address such interactions in the relevant ecosystem (e.g., the gut or oral cavity).

2.1.1 Viruses and Bacteriophages

Bacteriophages (phages), viruses of bacteria, are of particular interest because of their proven role in shaping microbial communities in many ecosystems (Fernández et al. 2018; Warwick-Dugdale et al. 2019). Furthermore, phages are abundantly present in the gut (estimated 1:1 ratio with bacteria), either as free phage or integrated into the bacterial genome as prophage (Reyes et al. 2012; Walk et al. 2016; Carding et al. 2017).

The many studies that have described a strong association of specific bacterial strains with ASCVD generally characterize the phylogenetic core, dynamics, and stability of the bacterial ecosystem by high-throughput 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing-based approaches. This precludes identification of integrated bacteriophage DNA in the bacterial DNA (see for recent reviews (Shetty et al. 2017; Hornung et al. 2018; Falony et al. 2019)). Increasingly accessible and affordable shotgun and long-read nanopore sequencing approaches together with rapidly emerging computational tools to unravel novel phage genomes are now rapidly solving part of the challenges phage researchers have faced in the past. These include the fact that the majority of gut bacteria (phage hosts) are strict anaerobes and thereby extremely difficult to culture. This has, until recent years, limited researchers to microscopic characterization of phages. The current collection of known gut phages therefore is a vast underrepresentation of the gut phageome. Interestingly, a healthy gut status in humans has been shown to mainly comprise integrated phages (Reyes et al. 2010; Minot et al. 2011), whereas cases of intestinal bowel disease have been associated with higher levels of free phages (Norman et al. 2015; Duerkop et al. 2018). Prophage integration has been shown to affect bacterial fitness and metabolic function in the gut (Duerkop et al. 2012; Hsu et al. 2019; Oh et al. 2019). Moreover, evidence for a direct role of phages in activation of the mammalian immune system, a critical element of ASCVD development, has recently been put forward (Gogokhia et al. 2019; Sweere et al. 2019). In line with long-standing observations that bacteriophages are able to pass the intestinal wall to enter the bloodstream, at least in experimental settings (Van Belleghem et al. 2019), these results support the urgency to carefully look into these viral members of the microbiome community in the gut and beyond. Implications for phages as modulators of (immune)metabolism are yet to be confirmed, but we predict this will be highly relevant for studies addressing the role of the microbiome in human ASCVD development.

3 Microbiome-Derived Metabolites

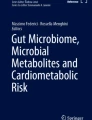

Gut bacteria are also considered to modulate human metabolism by production of small molecules including conversion of dietary components into hormone-like signals or biologically active metabolites (Fig. 2). It has been estimated that about 10% of the small molecules in the circulation are derived from the gut microbiome (Holmes et al. 2012). This estimate can very well be an underestimation because despite the major advances in development of metabolomics in the last decade, most circulating metabolites whether endogenous or microbial have not yet been identified.

Gut microbial metabolites have been implicated in ASCVD development. Primary bile acids are produced by the liver after which a small percentage is converted to secondary bile acids by colonic bacteria. Although evidence from human trials addressing if secondary bile acids might prevent ASCVD development is still warranted, secondary read outs associated with ASCVD (e.g., inflammation and LDL-C levels) have been reported to be reduced by bacteria capable of converting primary to secondary bile acids. TMA is produced by the microbiota from choline or carnitine precursors. In the liver, TMA is converted to TMAO which has been extensively linked to ASCVD development. ImP is a microbial metabolite of histidine. ImP directly inhibits insulin receptor-mediated signaling thereby leading to insulin resistance, a significant risk factor for the development of ASCVD. Whether ImP indeed affects ASCVD development is yet to be established. SCFA is a microbial fermentation product of complex carbohydrates. Many health benefits have been addressed to SCFA and include improved gut barrier function and reduced inflammation. Please see text for details

3.1 TMAO

A wonderful example of how a bacterial metabolite can be identified to exert effect on ASCVD comes from the studies of the Hazen group in Cleveland Clinic (Zhu et al. 2017; Koeth et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2014). They demonstrated that nutrients such as choline and carnitine can be converted to trimethylamine (TMA) by gut bacteria that express TMA lyases. The gas TMA subsequently diffuses from the intestine into the circulation and is converted to trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) in the liver by the hepatic enzyme flavine monooxygenase 3 (FMO3) (Brown and Hazen 2015). TMAO activates atherosclerosis in mouse models, and TMAO plasma levels have been shown to correlate with incidence of cardiovascular disease in humans in a number of studies (Zhu et al. 2016, 2017). Several other studies, however, failed to show this correlation (Heianza et al. 2017; Kaysen et al. 2015; Mueller et al. 2015; Aldana-Hernández et al. 2019). Zhu et al. showed that TMAO may exert its action via influencing blood platelet hyperresponsiveness and thrombosis, which provides a mechanistic link between TMAO and cardiovascular risk (Zhu et al. 2016, 2017). Recently, Chen et al. showed that TMAO may induce ER stress (Chen et al. 2019). Unravelling the metabolic pathways involved in TMAO metabolism provides a beautiful example how the interaction between microbial activity and host metabolism can be elucidated. By developing specific inhibitors of TMA lyases, the Hazen group (Koh et al. 2018) may have produced the tools to treat patients at risk for ACSVD due to increased TMAO (Wang et al. 2015). In the original paper in which the Hazen group introduced the TMAO pathway, additional ASCVD-associated peaks in the MS spectra were observed (Wang et al. 2011). Characterization of these putative metabolites has not yet been published, but it seems justified to suggest that there is more to come.

3.2 Imidazole-Propionate

Metabolites produced by microbial metabolism of aromatic amino acids are good candidates. Recently the histidine derivative imidazole-propionate (ImP) has been linked to insulin resistance in humans. By detailed analysis of portal blood obtained from obese diabetic patients compared to “healthy” (nondiabetic) obese controls, the group was able to single out ImP as one of the compounds strongly increased in portal blood from the diabetics (Koh et al. 2018). The group of Backhed subsequently characterized the molecular mechanism of action in great detail (Koh et al. 2018). Extensive mechanistic studies in mice revealed that ImP impairs insulin signaling via p38 protein kinase. Identification of ImP is very recent, and its putative role in ASCVD has not been investigated yet. Since ASCVD is an almost inevitable comorbidity of diabetes, an aggravating effect of IMP on ASCVD may be expected to be published in the near future.

3.3 Short-Chain Fatty Acids

The short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) butyrate, propionate, and acetate are produced from colonic fermentation of complex fibers by the gut microbiota. SCFAs are the main product of the digestive actions of the gut microbiota making them interesting candidates in the quest for microbial-derived metabolites influencing ASCVD. Lower levels of SCFA or SCFA-producing bacteria have been correlated with arterial stiffness, high blood pressure, and related end-organ damage (Pluznick 2013; Kim et al. 2018; Menni et al. 2018). Despite the abundant literature on diverse aspects of SCFA, metabolism insight in their impact on ASCVD in humans is limited to association studies. However, interesting effects have been observed in studies in animal models. A case in point is the recent study of Kasahara et al. in Nature Microbiology (Kasahara et al. 2018) that focused on the ameliorating action of butyrate on atherosclerotic plaque progression in ApoE −/− mice. Germ-free ApoE−/− mice were first colonized with a mixture of eight low butyrate-producing bacterial strains. Subsequently, mice were inoculated with the high butyrate-producing strain Roseburia intestinalis as well. This led to a significant reduction in atherosclerotic plaque size (compared to controls). Interestingly, butyrate, whether added to diet or produced by the bacteria, had no effect on plasma cholesterol or TMAO levels. The observed beneficial effect on plaque progression seemed mainly due to a tightening of gut barrier function which potentially reduces translocation of LPS in this animal model. This local effect of butyrate makes sense because this particular SCFA is almost completely metabolized by the colonic enterocytes. Besides this putative effect on gut barrier function, which clearly requires confirmation, SCFA have been implicated in modulation of inflammatory processes (Ohira et al. 2017). The G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 serve as SCFA receptors and have been shown to elicit intracellular signal transduction cascades mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and protein kinase C (PKC) (den Besten et al. 2013). In addition, butyrate has been shown to inhibit histone deacetylases, thereby altering the acetylation state of histones and other proteins which may induce epigenetic changes in gene transcription (Vinolo et al. 2011). A direct effect of SCFAs on expression of COX1 and 2 and hence possibly on eicosanoid production, important regulators of inflammatory processes, has also been proposed (Nurmi et al. 2005; Al-Lahham et al. 2010).

Most studies aiming at increasing insight into the molecular mechanism via which SCFA exert influence on inflammatory processes derive from in vitro experiments with cultured cells or tissues (Vinolo et al. 2011). Butyrate and propionate have been shown to affect neutrophil function by increasing apoptosis via a caspase-dependent pathway (Aoyama et al. 2010). A problem with most in vitro studies is that supraphysiological concentrations are used to show the effects making translation to the human situation difficult. Furthermore, acetate, butyrate, and propionate sometimes exhibit contrasting effects (Cavaglieri et al. 2003) leading to controversy on their modes of action. It can, however, not be excluded that the SCFA concentration required to elicit an anti-inflammatory response varies with the type of inflammation (Al-Lahham et al. 2010).

Confirmation of the anti-inflammatory properties that are often associated with SCFA comes from animal experiments. In ApoE knockout mice, feeding with butyrate reduced atherosclerotic lesions and lowered macrophage migration accompanied by a decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines (Aguilar et al. 2014). In mice treated intraperitoneally with acetate, inflammatory processes after kidney injuries were decreased leading to attenuation of the detrimental effects of inflammation on renal function (Andrade-Oliveira et al. 2015). Conversely, after systemic administration of supraphysiological doses of SCFA, renal tissue inflammation was increased due to dysregulation of T-cell response (Park et al. 2016). In another study in mice, SCFA receptors GPR41 and GPR43 were found to be required for an inflammatory response to bacterial infection and thus a protective pro-inflammatory response (Kim et al. 2013). In rodent models of colitis, oral acetate administration was shown to be protective (Masui et al. 2013).

As far as we are aware, no outcome trials have been carried out focusing on the effect of SCFA on ASCVD. However, a few human studies looked at the effect of SCFA on inflammatory aspects. A recent study investigated the effect of colonic infusions of SCFA, in concentrations found in the gut, on fasting levels of cytokines in overweight and obese subjects. The pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β decreased with a high acetate (60%) containing SCFA mixture compared to placebo and was significantly lower compared to a SCFA mixture containing high propionate (35%). Postprandial IL-1β levels as well as other pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 did not change in the obese subjects neither in the fasting nor in the postprandial period (Canfora et al. 2017). In the study by van der Beek et al. (2016), a tendency for lower fasting plasma TNF-α concentrations was found after distal colonic acetate infusion with a 100 mmol/L yet not with a 180 mmol/L, as well as after proximal colonic acetate infusion.

3.4 Other Microbiome-Produced Metabolites Associated with ASCVD

A number of studies have appeared recently that aimed to identify bacteria as well as metabolites associated with different stages of cardiovascular disease (Wang et al. 2019; Würtz et al. 2015; Kurilshikov et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019). Using a metagenomics approach, Kurilshikov et al. could link metabolic pathways encoded in the various bacteria to ASCVD risk but assessed risk directly in only one of the studied cohorts by measuring carotid IMT. In the other cohorts, a metabolic risk score was calculated from 33 established ASCVD biomarkers. An advantage of the metagenomics approach is that functional relations between ASCVD risk and microbial pathway can be identified. This is important because many bacterial strains share metabolic pathways. ASCVD risk is associated strongly with pathways involved in amino acid metabolism (Newgard 2017). Metabolomics was investigated in this study using the NMR-based Nightingale platform which focuses mainly on lipoproteins, and the expected relations between ApoB-containing lipoproteins and ASCVD risk were observed. Using a multi-omics approach, in which state-of-the-art metabolomics was combined with 16S rRNA sequencing, a number of metabolic pathways and co-abundant bacterial groups were identified to associate with ASCVD severity (Liu et al. 2019). Although ASCVD severity was determined using coronary angiography, which enables accurate diagnosis of the extent of plaque formation, this limits the number patients that can be studied. By grouping bacteria by co-abundance, functional properties of these groups could be predicted linking ASCVD risk to taurine, sphingolipid, ceramide, and benzene metabolism. Identification of xenobiotics links environmental variables directly to microbiota and host metabolism which could lead in future studies to identification of molecular mechanisms.

4 Bile Acids

The most important endogenous molecules that undergo microbial modifications are the family of bile acids (BA).

4.1 Bile Acid Metabolism

These molecules are produced exclusively by the liver via two pathways that start separately but fuse after four steps to share most of the subsequent steps in the parts that produce the primary bile acid chenodeoxycholic acid (Kuipers et al. 2014). The so-called classic bile acid synthesis pathway starts with the conversion of cholesterol into 7-alpha-cholesterol catalyzed by the enzyme 7-alpha-hydroxylase and produce either cholic acid or chenodeoxycholic acid. In humans, this has been postulated to be the major pathway, but this hypothesis requires experimental validation. After synthesis is completed via a complex pathway consisting of enzymatic steps in the cellular cytosol as well as mitochondria, the molecules are conjugated in peroxisomes with either glycine or taurine (Russell 2003; Chiang and Ferrell 2019). In humans the ratio glycine/taurine is mostly around 3; rodents predominantly conjugate with taurine (Kuipers et al. 2014). Another substantial difference between rodents and humans is the fact that rodents convert the hydrophobic chenodeoxycholic acid into the very hydrophilic muricholic acids. This completely alters BA function and precludes direct translation of rodent data to humans (Kuipers et al. 2014).

In mice and man, BA are stored in the gallbladder and are expelled into the duodenum primarily after initiating intake of food (Behar 2013). The consensus is that sensors in the small intestine register arrival of fat and protein and activate gallbladder contraction through release of cholecystokinin, although also in the absence of food regular small contraction of the gallbladder must occur to maintain BA concentrations observed in the circulation (Sips et al. 2018). BA arriving in the terminal ileum are extremely efficiently absorbed via the sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT or SLC10A2) (Hagenbuch and Dawson 2004). Bile acids are highly toxic for bacteria which is probably an important reason why the small intestine is sparsely colonized relative to the colon. Depending on small intestinal motility and the bile salt hydrolase activity of the microbiota colonizing the small intestine, a small amount of bile acids enters the colon and is metabolized into a myriad of so-called secondary or more recently tertiary bile acids. The degree of metabolism strongly depends on the colonic microbiota composition of a given subject (Ridlon et al. 2006).

Secondary bile acids are hydrophobic and consequently highly toxic for bacteria; apparently bacteria that are able to dehydroxylate bile acids have evolved to create a toxic environment for their neighbors. Because of the fact that the secondary bile acids are hydrophobic, they can passively diffuse across the colonocyte cell membranes and enter the bloodstream. Whether this process is purely diffusion or whether transporters are also involved is not known. In humans, it is estimated that about 5% of the bile acid pool is not reabsorbed and is excreted via the feces. The variability may in part be caused by changes in absorptive capacity which might directly influence the risk on ASCVD. Note that although only 5% of the bile acids escapes the enterohepatic circulation, bile acid excretion is the major pathway for cholesterol export from the body, apart from neutral sterol excretion. Aging correlates negatively with bile acid synthesis (Einarsson et al. 1985); thus also cholesterol excretion via this route decreases with age pointing to a possible causal relation between BA excretion and ASCVD. The plasma concentration of taurocholate has been found to negatively correlate with longevity (Cheng et al. 2015). This could be due to increased absorptive capacity possibly increasing with age and also accounting for the decrease in synthesis, but this still has to be addressed experimentally. One report has described a negative correlation between bile acid synthesis rates and ASCVD events (Charach et al. 2018). Though highly interesting this study requires confirmation.

4.2 Regulation by Bile Acids

Besides the direct role of BA in cholesterol metabolism, they control diverse metabolic pathways via membrane and nuclear hormone receptors signaling. Particularly G-protein linked receptor TGR5 and the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) are important in this respect. Both receptors show a great preference for the more hydrophobic bile acids; hence microbial metabolism plays a major role in regulating BA control of metabolism.

The role of FXR in controlling progress of ASCVD is ambiguous. Hanniman et al. reported increased atherosclerosis development in FXR/ApoE double KO mice (Hanniman et al. 2005), whereas two other studies reported that loss of FXR in low-density lipoprotein receptor −/− (LDLR) mice and ApoE−/− mice reduced atherosclerotic lesion size (Guo et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2006). Although differences in gut microbiota composition and sex of the mouse models used may play a role, the exact nature of these discrepancies is unclear. In contrast, FXR stimulation with the FXR agonists PX20606 and WAY-362450 did prevent atherosclerotic plaque formation in ApoE KO, LDLR −/−, or CETP transgene LDLR −/− models (Hartman et al. 2009; Hambruch et al. 2012). Additionally, FXR stimulation modulates inflammatory responses, thereby reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production. The first FDA-approved FXR agonist obeticholic acid (OCA) is currently tested in human trials (Neuschwander-Tetri et al. 2015). Unexpectedly, OCA induced an increase in LDL cholesterol and a concomitant decrease in HDL-C (Nevens et al. 2016). The underlying mechanism is not clear, and the effect on ASCVD has not yet been assessed; but the induced phenotype makes OCA a less attractive option to treat atherosclerosis in humans.

The other important BA receptor, TGR5, has a high affinity for secondary BA in particular lithocholate (Klindt et al. 2015). TGR5 stimulation activates thyroid hormone deiodinase 2 which converts inactive thyroxine (T4) into active 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine 12 (T3) and stimulates energy expenditure (Watanabe et al. 2006). Interestingly, TGR5 activation has immunosuppressive effects. TGR5 has been shown to reduce cytokine expression via inhibition of nuclear translocation of NF-κB (Pols et al. 2011; Yoneno et al. 2013). Furthermore, TGR5 activation with INT-777 inhibits the inflammasome, a major driver of the inflammatory component of ASCVD progression (Hao et al. 2017). In addition to its effects on immune cells, TGR5 also effects metabolism in endothelial cells (Keitel et al. 2007) where it may control nitric oxide (NO) production, through phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (Kida et al. 2013). The immunomodulatory functions of TGR5 make this receptor an interesting target to treat atherosclerosis, and because of its high affinity for lithocholic acid and deoxycholic acid, it may explain beneficial effects of the gut microbiota in ASCVD. So far, the effects of specific TGR5 agonists have only been studied in animal models; hence it is not clear whether the results can be translated to humans.

5 Summary and Future Perspectives

The etiology of ASCVD starts simple with disposition of lipids in the vessel wall but develops into an extremely complex myriad of aggravating and inhibiting factors when it progresses. Because so many factors are involved, it seems justified to assume that ASCVD develops in a unique way in any single patient. Up to now treatment of ASCVD mainly focuses on inhibiting the initiating factor, disposition of lipid in the vessel wall. Although perhaps successful in inhibiting progress of the disease, it does not induce regression of the plaques to a significant extent. Attempts to induce plaque regression have been very unsuccessful so far. Enhancing cholesterol efflux through increasing plasma HDL concentration has not worked probably by a lack of understanding of the molecular mechanism of cholesterol efflux in vivo.

The question arises whether influencing the composition of the microbiome can help. As discussed in this review, the bacterial component of the microbiome can influence the process of ASCVD development at many different stages. Particularly, the oral microbiome can easily invade a patient suffering from a very common periodontitis. This causes a systemic inflammatory response potentially aggravating atherosclerotic plaque progression.

Bacteria can initiate production of harmful molecules such as TMA or ImP that are likely to contribute to ASCVD development. Since many bacterial species are capable of TMA or ImP production, it is challenging to develop strategies to, e.g., eradicate these bacteria. Antibiotics treatment has been shown to reduce TMAO production in humans (Craciun and Balskus 2012) However, it is critical to point out that there are many objections to using antibiotics as means to intervene in microbiome-mediated cues to ASCVD development. These include significant consequences of antibiotic use for the gut microbial community, risk to develop antibiotic resistance, and the fact that antibiotics use has been associated with increased progression of ASCVD (Heianza et al. 2019).

Early initiatives aiming to specifically reduce production of TMA (instead of the bacterium) have shown promising results in lowering TMAO levels and ASCVD risk, at least in mice. Inhibition of the activity of TMA lyase, which hydrolyses choline to TMA, using the choline analog DMB reduced atherosclerosis burden in ApoE−/− mice fed a choline-rich diet (Wang et al. 2015). More recently, it was shown that strategies aiming to inhibit phospholipase D, a bacterial enzyme that frees choline from phosphatidylcholine lipids, might be an interesting novel target to reduce choline-derived production of TMA (Chittim et al. 2019). More upstream in the cascade of microbial-metabolite production, it might be beneficial to develop strategies that aim to reduce intake of precursors of the presumably harmful metabolites. Although it is too early to tell if reduction of choline intake or alternative dietary strategies to reduce TMAO production will prevent ASCVD development (Washburn et al. 2019), these initiatives might provide feasible and economic solutions for reduction of these and other (e.g., ImP from histidine) microbiome-derived atherogenic metabolites. Important in this context is that humans usually have very low coherence to dietary interventions. In addition, high interindividual differences in response to dietary interventions (Walker et al. 2011; Cotillard et al. 2013; Kovatcheva-Datchary et al. 2015) make diet a challenging intervention to alter the microbiome and (markers of) ASCVD development.

The microbial modification of primary into secondary bile acids is in part facilitated by the bacterial enzyme bile salt hydrolase (BSH). BSH activity has been postulated to alter cholesterol accumulation, inflammation, and atherosclerosis development (Tremaroli and Bäckhed 2012), and BSH activity is present in a very wide range of bacteria (Joyce et al. 2014). A modified E. coli strain carrying the BSH gene was shown to enhance expression of genes involved in cholesterol efflux, immune homeostasis, and energy metabolism in mice (Joyce et al. 2014). In line, a dedicated intervention study using BSH-active Lactobacillus reuteri in hypercholesterolemic humans showed that this probiotic effectively lowered LDL-C compared to placebo-treated subjects (Jones et al. 2012). Of interest in this context is that many probiotic strains are characterized by BSH activity (Begley et al. 2006). Whether or not the BSH activity underlies the beneficial effects of probiotic strain administration on parameters of ASCVD risk/health remains to be determined. Nevertheless, many probiotic strains have been associated with ASCVD health. Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus plantarum have been associated with lowering of cholesterol (Tahri et al. 1996). Interestingly, Lactobacillus plantarum (Nguyen et al. 2007) and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (Qiu et al. 2018) were also reported to decrease TMAO and atherosclerosis development in mice prone to develop the disease. Likewise, in hypercholesterolemic humans, Lactobacillus rhamnosus was reported to reduce cholesterol levels (Costabile et al. 2017).

One can speculate that beneficial bacteria may produce molecules that halt or even induce regression of the process. As far as we know, studies to find these compounds have not been carried out. A good strategy may be to use modern machine learning methods to analyze the plasma of subjects with atherogenic plasma profile that do not show signs of ASCVD.

References

Aderem A, Underhill DM (1999) Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages [in process citation]. Annu Rev Immunol 17:593

Aguilar EC, Leonel AJ, Teixeira LG et al (2014) Butyrate impairs atherogenesis by reducing plaque inflammation and vulnerability and decreasing NFκB activation. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 24:606–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2014.01.002

Aldana-Hernández P, Leonard K-A, Zhao Y-Y et al (2019) Dietary choline or trimethylamine N-oxide supplementation does not influence atherosclerosis development in Ldlr−/− and Apoe−/− male mice. J Nutr 150:249–255. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxz214

Al-Lahham SH, Peppelenbosch MP, Roelofsen H et al (2010) Biological effects of propionic acid in humans; metabolism, potential applications and underlying mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1801:1175–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.07.007

Andrade-Oliveira V, Amano MT, Correa-Costa M et al (2015) Gut Bacteria products prevent AKI induced by ischemia-reperfusion. J Am Soc Nephrol 26:1877–1888. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2014030288

Aoyama M, Kotani J, Usami M (2010) Butyrate and propionate induced activated or non-activated neutrophil apoptosis via HDAC inhibitor activity but without activating GPR-41/GPR-43 pathways. Nutrition 26:653–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2009.07.006

Aron-Wisnewsky J, Clément K (2016) The gut microbiome, diet, and links to cardiometabolic and chronic disorders. Nat Rev Nephrol 12:169. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2015.191

Begley M, Hill C, Gahan CGM (2006) Bile salt hydrolase activity in probiotics. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:1729

Behar J (2013) Physiology and pathophysiology of the biliary tract: the gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi—a review. ISRN Physiol 2013:1. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/837630

Brandsma E, Kloosterhuis NJ, Koster M et al (2019) A Proinflammatory gut microbiota increases systemic inflammation and accelerates atherosclerosis. Circ Res 124:94. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313234

Brown JM, Hazen SL (2015) The gut microbial endocrine organ: bacterially derived signals driving Cardiometabolic diseases. Annu Rev Med 66:343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-060513-093205

Canfora EE, van der Beek CM, Jocken JWE et al (2017) Colonic infusions of short-chain fatty acid mixtures promote energy metabolism in overweight/obese men: a randomized crossover trial. Sci Rep 7:2206. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02546-x

Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Fava F et al (2007) Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia. Diabetologia 50:2374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-007-0791-0

Carding SR, Davis N, Hoyles L (2017) Review article: the human intestinal virome in health and disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 46:800

Cavaglieri CR, Nishiyama A, Fernandes LC et al (2003) Differential effects of short-chain fatty acids on proliferation and production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by cultured lymphocytes. Life Sci 73:1683–1690

Charach G, Argov O, Geiger K et al (2018) Diminished bile acids excretion is a risk factor for coronary artery disease: 20-year follow up and long-term outcome. Ther Adv Gastroenterol 11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756283X17743420

Chen S, Henderson A, Petriello MC et al (2019) Trimethylamine N-oxide binds and activates PERK to promote metabolic dysfunction. Cell Metab 30:1141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.021

Cheng S, Larson MG, McCabe EL et al (2015) Distinct metabolomic signatures are associated with longevity in humans. Nat Commun 6:6791. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7791

Chiang JYL, Ferrell JM (2019) Bile acids as metabolic regulators and nutrient sensors. Annu Rev Nutr 39:175. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-082018-124344

Chittim CL, Martínez del Campo A, Balskus EP (2019) Gut bacterial phospholipase Ds support disease-associated metabolism by generating choline. Nat Microbiol 4:155. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0294-4

Costabile A, Buttarazzi I, Kolida S et al (2017) An in vivo assessment of the cholesterol-lowering efficacy of lactobacillus plantarum ECGC 13110402 in normal to mildly hypercholesterolaemic adults. PLoS One 12:e0187964. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187964

Cotillard A, Kennedy SP, Kong LC et al (2013) Dietary intervention impact on gut microbial gene richness. Nature 500:585. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12480

Craciun S, Balskus EP (2012) Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:21307. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1215689109

den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK et al (2013) The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res 54:2325. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.r036012

Duerkop BA, Clements CV, Rollins D et al (2012) A composite bacteriophage alters colonization by an intestinal commensal bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109:17621. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1206136109

Duerkop BA, Kleiner M, Paez-Espino D et al (2018) Murine colitis reveals a disease-associated bacteriophage community. Nat Microbiol 3:1023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0210-y

Einarsson K, Nilsell K, Leijd B, Angelin B (1985) Influence of age on secretion of cholesterol and synthesis of bile acids by the liver. N Engl J Med 313:277. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm198508013130501

Emoto T, Yamashita T, Sasaki N et al (2016) Analysis of gut microbiota in coronary artery disease patients: a possible link between gut microbiota and coronary artery disease. J Atheroscler Thromb 23:908. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.32672

Falony G, Vandeputte D, Caenepeel C et al (2019) The human microbiome in health and disease: hype or hope. Acta Clin Belgica 74:53. https://doi.org/10.1080/17843286.2019.1583782

Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I et al (2017) Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J 38:2459–2472. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144

Fernández L, Rodríguez A, García P (2018) Phage or foe: an insight into the impact of viral predation on microbial communities. ISME J 12:1171

Gogokhia L, Buhrke K, Bell R et al (2019) Expansion of bacteriophages is linked to aggravated intestinal inflammation and colitis. Cell Host Microbe 25:285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2019.01.008

Gregory JC, Buffa JA, Org E et al (2015) Transmission of atherosclerosis susceptibility with gut microbial transplantation. J Biol Chem 290:5647. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.618249

Guo GL, Santamarina-Fojo S, Akiyama TE et al (2006) Effects of FXR in foam-cell formation and atherosclerosis development. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1761:1401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.09.018

Hagenbuch B, Dawson P (2004) The sodium bile salt cotransport family SLC10. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol 447:566

Hajishengallis G (2015) Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 15:30–44

Hambruch E, Miyazaki-Anzai S, Hahn U et al (2012) Synthetic farnesoid X receptor agonists induce high-density lipoprotein-mediated transhepatic cholesterol efflux in mice and monkeys and prevent atherosclerosis in cholesteryl ester transfer protein transgenic low-density lipoprotein receptor (−/−) mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 343:556. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.112.196519

Hanniman EA, Lambert G, McCarthy TC, Sinal CJ (2005) Loss of functional farnesoid X receptor increases atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Lipid Res 46:2595. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.m500390-jlr200

Hao H, Cao L, Jiang C et al (2017) Farnesoid X receptor regulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome underlies cholestasis-associated sepsis. Cell Metab 25:856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.03.007

Hartman HB, Gardell SJ, Petucci CJ et al (2009) Activation of farnesoid X receptor prevents atherosclerotic lesion formation in LDLR −/− and apoE −/− mice. J Lipid Res 50:1090. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.m800619-jlr200

Heianza Y, Ma W, Manson JAE et al (2017) Gut microbiota metabolites and risk of major adverse cardiovascular disease events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Heart Assoc 6:e004947

Heianza Y, Zheng Y, Ma W et al (2019) Duration and life-stage of antibiotic use and risk of cardiovascular events in women. Eur Heart J 40:3838. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz231

Hoffmann C, Dollive S, Grunberg S et al (2013) Archaea and fungi of the human gut microbiome: correlations with diet and bacterial residents. PLoS One 8:e66019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066019

Holmes E, Li JV, Marchesi JR, Nicholson JK (2012) Gut microbiota composition and activity in relation to host metabolic phenotype and disease risk. Cell Metab 16:559

Holmes MV, Ala-Korpela M, Smith GD (2017) Mendelian randomization in cardiometabolic disease: challenges in evaluating causality. Nat Rev Cardiol 14:577

Hornung B, Martins dos Santos VAP, Smidt H, Schaap PJ (2018) Studying microbial functionality within the gut ecosystem by systems biology. Genes Nutr 13:5

Hsu BB, Gibson TE, Yeliseyev V et al (2019) Dynamic modulation of the gut microbiota and Metabolome by bacteriophages in a mouse model. Cell Host Microbe 25:803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2019.05.001

Huseyin CE, O’Toole PW, Cotter PD, Scanlan PD (2017) Forgotten fungi-the gut mycobiome in human health and disease. FEMS Microbiol Rev 41:479

Jie Z, Xia H, Zhong SL et al (2017) The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun 8:845. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00900-1

Jones ML, Martoni CJ, Parent M, Prakash S (2012) Cholesterol-lowering efficacy of a microencapsulated bile salt hydrolase-active Lactobacillus reuteri NCIMB 30242 yoghurt formulation in hypercholesterolaemic adults. Br J Nutr 107:1505. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114511004703

Jonsson A, Hållenius FF, Akrami R et al (2017) Bacterial profile in human atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis 263:177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.06.016

Jonsson AL, Caesar R, Akrami R et al (2018) Impact of gut microbiota and diet on the development of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 38:2318. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311233

Joyce SA, MacSharry J, Casey PG et al (2014) Regulation of host weight gain and lipid metabolism by bacterial bile acid modification in the gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:7421–7426. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1323599111

Karlsson FH, Fåk F, Nookaew I et al (2012) Symptomatic atherosclerosis is associated with an altered gut metagenome. Nat Commun 3:1245. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2266

Kasahara K, Tanoue T, Yamashita T et al (2017) Commensal bacteria at the crossroad between cholesterol homeostasis and chronic inflammation in atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res 58:519. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.m072165

Kasahara K, Krautkramer KA, Org E et al (2018) Interactions between Roseburia intestinalis and diet modulate atherogenesis in a murine model. Nat Microbiol 3:1461. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0272-x

Kaysen GA, Johansen KL, Chertow GM et al (2015) Associations of Trimethylamine N-oxide with nutritional and inflammatory biomarkers and cardiovascular outcomes in patients new to dialysis. J Ren Nutr 25:351. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2015.02.006

Keitel V, Reinehr R, Gatsios P et al (2007) The G-protein coupled bile salt receptor TGR5 is expressed in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Hepatology 45:695. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21458

Kida T, Tsubosaka Y, Hori M et al (2013) Bile acid receptor tgr5 agonism induces no production and reduces monocyte adhesion in vascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33:1663. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301565

Kim MH, Kang SG, Park JH et al (2013) Short-chain fatty acids activate GPR41 and GPR43 on intestinal epithelial cells to promote inflammatory responses in mice. Gastroenterology 145:396–406.e10. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.056

Kim S, Goel R, Kumar A et al (2018) Imbalance of gut microbiome and intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction in patients with high blood pressure. Clin Sci 132:701. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20180087

Klindt C, Deutschmann K, Reich M et al (2015) TGR5 knockout mice are highly susceptible to LCA induced liver damage. Z Gastroenterol 53. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1568049

Koeth RA, Lam-Galvez BR, Kirsop J et al (2019) L-Carnitine in omnivorous diets induces an atherogenic gut microbial pathway in humans. J Clin Invest 129:373. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI94601

Koh A, Molinaro A, Ståhlman M et al (2018) Microbially produced imidazole propionate impairs insulin signaling through mTORC1. Cell 175:947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.055

Koren O, Spor A, Felin J et al (2011) Human oral, gut, and plaque microbiota in patients with atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:4592. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011383107

Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Nilsson A, Akrami R et al (2015) Dietary fiber-induced improvement in glucose metabolism is associated with increased abundance of Prevotella. Cell Metab 22:971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.001

Kuipers F, Bloks VW, Groen AK (2014) Beyond intestinal soap – bile acids in metabolic control. Nat Rev Endocrinol 10:488

Kurilshikov A, van den Munckhof ICL, Chen L et al (2019) Gut microbial associations to plasma metabolites linked to cardiovascular phenotypes and risk. Circ Res 124:1808. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314642

Laforest-Lapointe I, Arrieta M-C (2018) Microbial eukaryotes: a missing link in gut microbiome studies. mSystems 3:e00201. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00201-17

Liu H, Chen X, Hu X et al (2019) Alterations in the gut microbiome and metabolism with coronary artery disease severity. Microbiome 7:68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-0683-9

Lobo MG, Schmidt MM, Lopes RD et al (2019) Treating periodontal disease in patients with myocardial infarction: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Intern Med 71:76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2019.08.012

Loos BG, Craandijk J, Hoek FJ et al (2005) Elevation of systemic markers related to cardiovascular diseases in the peripheral blood of periodontitis patients. J Periodontol 71:1528. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1528

Masui R, Sasaki M, Funaki Y et al (2013) G protein-coupled receptor 43 moderates gut inflammation through cytokine regulation from mononuclear cells. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19:2848–2856. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MIB.0000435444.14860.ea

Menni C, Lin C, Cecelja M et al (2018) Gut microbial diversity is associated with lower arterial stiffness in women. Eur Heart J 39:2390. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy226

Minot S, Sinha R, Chen J et al (2011) The human gut virome: inter-individual variation and dynamic response to diet. Genome Res 21:1616. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.122705.111

Mueller DM, Allenspach M, Othman A et al (2015) Plasma levels of trimethylamine-N-oxide are confounded by impaired kidney function and poor metabolic control. Atherosclerosis 243:638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.10.091

Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ et al (2015) Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 385:956. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61933-4

Nevens F, Andreone P, Mazzella G et al (2016) A placebo-controlled trial of Obeticholic acid in primary biliary cholangitis. N Engl J Med 375:631. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1509840

Newgard CB (2017) Metabolomics and metabolic diseases: where do we stand? Cell Metab 25:43–56

Nguyen TDT, Kang JH, Lee MS (2007) Characterization of Lactobacillus plantarum PH04, a potential probiotic bacterium with cholesterol-lowering effects. Int J Food Microbiol 113:358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.08.015

Noack B, Genco RJ, Trevisan M et al (2005) Periodontal infections contribute to elevated systemic C-reactive protein level. J Periodontol 72:1221. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2000.72.9.1221

Nordestgaard BG (2016) Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: new insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. Circ Res 118:547. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306249

Norman JM, Handley SA, Baldridge MT et al (2015) Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 160:447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.002

Nurmi JT, Puolakkainen PA, Rautonen NE (2005) Bifidobacterium Lactis sp. 420 up-regulates cyclooxygenase (Cox)-1 and down-regulates Cox-2 gene expression in a Caco-2 cell culture model. Nutr Cancer 51:83–92. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327914nc5101_12

Oh JH, Alexander LM, Pan M et al (2019) Dietary fructose and microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids promote bacteriophage production in the gut symbiont lactobacillus reuteri. Cell Host Microbe 25:273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2018.11.016

Ohira H, Tsutsui W, Fujioka Y (2017) Are short chain fatty acids in gut microbiota defensive players for inflammation and atherosclerosis? J Atheroscler Thromb 24:660. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.rv17006

Park J, Goergen CJ, HogenEsch H, Kim CH (2016) Chronically elevated levels of short-chain fatty acids induce T cell-mediated ureteritis and hydronephrosis. J Immunol 196:2388–2400. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1502046

Paterson MJ, Oh S, Underhill DM (2017) Host–microbe interactions: commensal fungi in the gut. Curr Opin Microbiol 40:131

Pencina MJ, Navar AM, Wojdyla D et al (2019) Quantifying importance of major risk factors for coronary heart disease. Circulation 139:1603. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031855

Pluznick JL (2013) A novel SCFA receptor, the microbiota, and blood pressure regulation. Gut Microbes 5:202. https://doi.org/10.4161/gmic.27492

Pols TWH, Nomura M, Harach T et al (2011) TGR5 activation inhibits atherosclerosis by reducing macrophage inflammation and lipid loading. Cell Metab 14:747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2011.11.006

Qiu L, Tao X, Xiong H et al (2018) Lactobacillus plantarum ZDY04 exhibits a strain-specific property of lowering TMAO via the modulation of gut microbiota in mice. Food Funct 9:4299. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8fo00349a

Rabot S, Membrez M, Bruneau A et al (2010) Germ-free C57BL/6J mice are resistant to high-fat-diet-induced insulin resistance and have altered cholesterol metabolism. FASEB J 24:4948. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.10-164921

Raetz CRH, Whitfield C (2008) Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins Christian. Annu Rev Biochem 71:635–700. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414

Reyes A, Haynes M, Hanson N et al (2010) Viruses in the faecal microbiota of monozygotic twins and their mothers. Nature 466:334. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09199

Reyes A, Semenkovich NP, Whiteson K et al (2012) Going viral: next-generation sequencing applied to phage populations in the human gut. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:607

Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T et al (2017) Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med 377:1119. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1707914

Ridlon JM, Kang D-J, Hylemon PB (2006) Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J Lipid Res 47:241. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.r500013-jlr200

Russell DW (2003) The enzymes, regulation, and genetics of bile acid synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem 72:137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161712

Shetty SA, Hugenholtz F, Lahti L et al (2017) Intestinal microbiome landscaping: insight in community assemblage and implications for microbial modulation strategies. FEMS Microbiol Rev 41:182. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuw045

Shkoporov AN, Hill C (2019) Bacteriophages of the human gut: the “known unknown” of the microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 25:195

Sips FLP, Eggink HM, Hilbers PAJ et al (2018) In silico analysis identifies intestinal transit as a key determinant of systemic bile acid metabolism. Front Physiol 9:631. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00631

Stepankova R, Tonar Z, Bartova J et al (2010) Absence of microbiota (germ-free conditions) accelerates the atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice fed standard low cholesterol diet. J Atheroscler Thromb 17:796. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.3285

Sweere JM, van Belleghem JD, Ishak H et al (2019) Bacteriophage trigger antiviral immunity and prevent clearance of bacterial infection. Science 363:eaat9691. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat9691

Tahri K, Grill JP, Schneider F (1996) Bifidobacteria strain behavior toward cholesterol: coprecipitation with bile salts and assimilation. Curr Microbiol 33:187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002849900098

Tilg H, Zmora N, Adolph TE, Elinav E (2019) The intestinal microbiota fuelling metabolic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 20:40. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0198-4

Torres De Heens GL, Loos BG, van der Velden U (2010) Monozygotic twins are discordant for chronic periodontitis: clinical and bacteriological findings. J Clin Periodontol 37:120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01511.x

Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F (2012) Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 489:242

van Belleghem JD, Dąbrowska K, Vaneechoutte M et al (2019) Interactions between bacteriophage, bacteria, and the mammalian immune system. Viruses 11:10

van der Beek CM, Canfora EE, Lenaerts K et al (2016) Distal, not proximal, colonic acetate infusions promote fat oxidation and improve metabolic markers in overweight/obese men. Clin Sci 130:2073–2082. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20160263

Vinolo MAR, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R (2011) Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients 3:858–876. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu3100858

Virmani R, Robinowitz M, Geer JC et al (1987) Coronary artery atherosclerosis revisited in Korean war combat casualties. Arch Pathol Lab Med 111:972–976

Walk ST, de Vos WM, van der Oost J et al (2016) Healthy human gut phageome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113:10400. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1601060113

Walker AW, Ince J, Duncan SH et al (2011) Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. ISME J 5:220. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2010.118

Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ et al (2011) Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 472:57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09922

Wang Z, Roberts AB, Buffa JA et al (2015) Non-lethal inhibition of gut microbial Trimethylamine production for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell 163:1585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.055

Wang Z, Zhu C, Nambi V et al (2019) Metabolomic pattern predicts incident coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 39:1475. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.118.312236

Warwick-Dugdale J, Buchholz HH, Allen MJ, Temperton B (2019) Host-hijacking and planktonic piracy: how phages command the microbial high seas. Virol J 16:15

Washburn RL, Cox JE, Muhlestein JB et al (2019) Pilot study of novel intermittent fasting effects on metabolomic and trimethylamine N-oxide changes during 24-hour water-only fasting in the FEELGOOD trial. Nutrients 11:246. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020246

Watanabe M, Houten SM, Mataki C et al (2006) Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature 439:484–489. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04330

Wright RS, Murphy J (2016) PROVE-IT to IMPROVE-IT why LDL-C goals still matter in post-ACS patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 67:362–364

Wright SD, Burton C, Hernandez M et al (2000) Infectious agents are not necessary for murine atherogenesis. J Exp Med 191:1437. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.191.8.1437

Wu J, Saleh MA, Kirabo A et al (2014) Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57:1470. https://doi.org/10.2337/db07-1403

Würtz P, Havulinna AS, Soininen P et al (2015) Metabolite profiling and cardiovascular event risk: a prospective study of 3 population-based cohorts. Circulation 131:774. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013116

Yoneno K, Hisamatsu T, Shimamura K et al (2013) TGR5 signalling inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by in vitro differentiated inflammatory and intestinal macrophages in Crohn’s disease. Immunology 139:19. https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12045

Yoshii S, Tsuboi S, Morita I et al (2009) Temporal association of elevated C-reactive protein and periodontal disease in men. J Periodontol 80:734. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2009.080537

Zhang Y, Wang X, Vales C et al (2006) FXR deficiency causes reduced atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26:2316. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.0000235697.35431.05

Zhu W, Gregory JC, Org E et al (2016) Gut microbial metabolite TMAO enhances platelet hyperreactivity and thrombosis risk. Cell 165:111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.011

Zhu W, Wang Z, Tang WW, Hazen SL (2017) Gut microbe-generated TMAO from dietary choline is prothrombotic in subjects. Circulation 135:1671. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40945-017-0033-9.Using

Acknowledgments

MN is supported by a ZONMW-VIDI grant 2013 [016.146.327] and a Dutch Heart Foundation CVON IN CONTROL Young Talent Grant 2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Herrema, H., Nieuwdorp, M., Groen, A.K. (2020). Microbiome and Cardiovascular Disease. In: von Eckardstein, A., Binder, C.J. (eds) Prevention and Treatment of Atherosclerosis . Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, vol 270. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2020_356

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2020_356

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86075-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86076-9

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)