Abstract

Exacerbated production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) is a key event in the progression of osteoarthritis (OA) and represents a promising target for the management of OA with nutraceuticals. In this study, we sought to determine the MMP-inhibitory activity of an ethanolic Caesalpinia sappan extract (CSE) in human OA chondrocytes. Thus, human articular chondrocytes isolated from OA cartilage and SW1353 chondrocytes were stimulated with Interleukin-1beta (IL1β), without or with pretreatment with CSE. Following viability assays, the production of MMP-2 and MMP-13 was assessed using ELISA, whereas mRNA levels of MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-13 and TIMP-1, TIMP-2, TIMP-3 were quantified using RT-qPCR assays. Chondrocytes were co-transfected with a MMP-13 luciferase reporter construct and NF-kB p50 and p65 expression vectors in the presence or absence of CSE. In addition, the direct effect of CSE on the proteolytic activities of MMP-2 was evaluated using gelatin zymography. We found that CSE significantly suppressed IL1β-mediated upregulation of MMP-13 mRNA and protein levels via abrogation of the NF-kB(p65/p50)-driven MMP-13 promoter activation. We further observed that the levels of IL1β-induced MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-7, and MMP-9 mRNA, but not TIMP mRNA levels, were down-regulated in chondrocytes in response to CSE. Zymographic results suggested that CSE did not directly interfere with the proteolytic activity of MMP-2. In summary, this study provides evidence for the MMP-inhibitory potential of CSE or CSE-derived compounds in human OA chondrocytes. The data indicate that the mechanism of this inhibition might, at least in part, involve targeting of NF-kB-mediated promoter activation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA), a chronic and degenerative joint disease, has the highest prevalence and economic impact among arthritic maladies. Besides mechanical and genetic factors, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL1β) or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) contribute to the impaired chondrocyte function and extracellular matrix (ECM) integrity in OA. Histological examination has demonstrated the localization of IL1β in the zones of degenerated OA cartilage (Saha et al. 1999) as well as in the synovial membranes and synovial fluids of OA patients (Smith et al. 1997; Kubota et al. 1997). At the cellular level, chondrocytes respond to this cytokine via a cascade of events leading to loss of balance between cartilage anabolism and catabolism, associated with phenotypic modulation and activation of the normally quiescent chondrocytes (Goldring and Marcu 2009; Goldring et al. 2008). In OA cartilage, IL1β and TNFα co-localize with increased levels of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (Tetlow et al. 2001), and IL1β was shown to upregulate MMP expression levels in normal human chondrocytes, OA chondrocytes, and chondrosarcoma cells (Tetlow et al. 2001; Fan et al. 2005; Mix et al. 2001).

According to their main substrate specificity, proteins of the MMP family can be divided into collagenases (MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-13), gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9), stromelysins (MMP-3, MMP-10, MMP-11), and membrane type I MMPs (MMP-14-17). Restriction of the proteolytic activities of MMPs is mediated by endogenous tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs) (Nagase and Woessner 1999). MMPs play important roles in physiological processes such as tissue repair, but also become part of destructive disease processes due both to its overexpression and the excessive activation of pro-MMPs into their active forms. Interestingly, a recent study by Little et al. demonstrated that MMP-13-knockout mice were less prone than wild-type mice to develop tibial cartilage structural damage following medial meniscal destabilization surgery in the knee (Little et al. 2009). Taken together, MMPs might represent promising targets for therapeutic intervention in OA.

To date, classic therapeutic approaches of OA are still limited to exercise, palliative drugs or surgical intervention. There is growing awareness, however, that nutritional factors can positively influence the maintenance of bone and joint health. Articular cartilage is critically dependent upon the regular provision of nutrients, vitamins, and essential trace elements (Goggs et al. 2005). Thus, dietary supplementation programs and nutraceuticals might provide long-term benefits to patients with a chronic disease such as OA. In general, the benefits offered by nutraceuticals are based on the lack of adverse effects and the targeting of multiple signaling pathways addressed by nutritional compound mixtures such as plant extracts (Bjorkman 1999). A comprehensive review on current nutraceuticals for the management of OA has been published elsewhere (Ameye and Chee 2006).

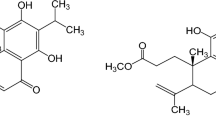

Caesalpinia sappan L. (Leguminosae) is distributed in Southeast Asia, and its dried heartwood (also known as Sappan wood) has been a traditional ingredient of food or beverages such as Bir Pletok, a Batavian spice drink. The extract was shown to lack toxic effects and to possess anti-atherogenic potential in rats based on its constituent hematein (Sireeratawong et al. 2010; Oh et al. 2001). In traditional Chinese medicine, Caesalpinia sappan is known to promote blood circulation and to possess analgesic or anti-inflammatory properties (China Pharmacopoeia 2010). In Japan, Sappan wood was listed in the 15th edition of the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (2006). A range of constituents including brazilin, hematoxylin, brazilein, photosappanin derivatives, flavones, and other homoisoflavonoids has been isolated from Caesalpinia sappan (Chen et al. 2008; Washiyama et al. 2009; Xie et al. 2000). Extracts of Caesalpinia sappan as well as some of their defined constituents have been investigated as functional food, revealing potential anti-inflammatory (Jeong et al. 2008), vasorelaxing (Xie et al. 2000), immunosuppressive (Ye et al. 2006), and hepatoprotective effects (Srilakshmi et al. 2010). At the time of finalizing this manuscript, Sun et al. published a study demonstrating the efficacy of a Caesalpinia sappan extract in an animal model of rheumatoid arthritis (Sun et al. 2011). Rats treated daily with 1.2, 2.4, or 3.6 g/kg extract showed reduced signs of paw swelling and arthritis severity as well as lower levels of proinflammatory mediators in the plasma as compared to untreated animals. The mechanisms underlying these effects, however, are still not fully understood.

The present study was driven by the hypothesis that the extract of Caesalpinia sappan (CSE) interferes with catabolic processes in human OA chondrocytes. We cultured human chondrocytes in the presence of IL1β and examined the biological effects of CSE co-treatment on the expression and activity of major MMPs. The results presented here demonstrate that CSE strongly inhibits chondrocyte catabolism by suppressing IL1β-induced MMPs mRNA and protein levels. We further present evidence that CSE interferes with MMP-13 promoter activation mediated by NF-kB subunits p50 and p65.

Materials and methods

Preparation and characterization of CSE

The heartwoods of Caesalpinia sappan were collected in June 2006 in San-Pa-Thong district, Chiang Mai province, Thailand, and identified by comparison with the voucher specimen (No. 87-1631) at the Herbarium Section, Northern Research Center for Medicinal Plants, Faculty of Pharmacy, Chiang Mai University, Thailand. Ethanolic extraction was performed by continuously extracting 30 g powdered heartwood in 350 ml 96% EtOH for 24 h using a Soxhlet apparatus. Then, the liquid extract was evaporated under reduced pressure to yield solid CSE. The composition of CSE has been described in detail previously (Chen et al. 2008). For further characterization, 4 batches of CSE were analyzed qualitatively using HPLC. Briefly, CSE samples were dissolved in MeOH (1 mg/ml), filtrated through a 0.2 μm sterile filter, and analyzed by HPLC (ICS-3000, Dionex, USA) using a Nucleodur C-18 column (Macherey–Nagel, D), a PDA-100 detector (Dionex) and a solvent gradient of MeOH and bidistilled H2O (both containing 2.5% acetic acid). At 280 nm, all 4 batches yielded congruent chromatograms which were also comparable to that of the standardized reference Natural Red 24 (MP Biomedicals, USA, LOT #: R25179), a commercially available Sappan wood extract (Supplementary Figure 1). For cell treatment, CSE was dissolved in 96% EtOH (10 mg/ml) and used in appropriate dilutions for the in vitro assays. The activity of specific components was not addressed in the current study.

Cell culture

Human articular cartilage was obtained from intact regions of femoral condyles and tibial plateaus at the time of total knee replacement surgery in OA patients with informed consent and in accordance with the terms of the ethics committee of the Medical University Vienna (EKNr.: 081/2005). Primary chondrocytes (PCs) were isolated according to standard protocols (Toegel et al. 2009), seeded at 105 cells/cm2, and grown in an atmosphere of humidified 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, A) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Biochrom AG, D) and gentamycin (complete medium). Only freshly isolated PCs were used for all assays throughout the study. Human SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells were seeded at 104 cells/cm2 and maintained in complete medium, whereas T/C28a2 immortalized chondrocytes were seeded at 104 cells/cm2 and cultured using DMEM/F12 containing 10% FCS. Prior to cell treatment, chondrocytes were starved for 6 h in serum-free DMEM containing 2% insulin-transferrin-selenium solution (Gibco, A) (ITS medium). Then, cells were pretreated for 1 h with CSE or vehicle in ITS medium followed by the addition of 10 ng/ml IL1β (Strathmann Biotec, D) and further incubation for the indicated times.

Viability assay

Primary chondrocytes were seeded at 3 × 103 cells/well into 96-well microplates (Iwaki, J), serum-starved, and treated in quadruplicate with serial dilutions of CSE for 72 h. Cell proliferation was evaluated using the MTT-based EZ4U cell proliferation assay (Biomedica, A) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The experiment was repeated twice with cells from different donors.

Gelatin zymography

Serum-starved cells were cultured in the presence of 5 μg/ml CSE for 48 h. Ten microliter of cell culture supernatant was mixed with 10 μl Sample buffer (0.5 M Tris–HCl, 20% Glycerol, 10% SDS, 0.1% Bromophenol Blue) and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were loaded on gelatin (1 mg/ml)—containing SDS–polyacrylamide gels for electrophoresis with constant voltage (125 V). After running, the gel was incubated in renaturation buffer (2.5% Triton X-100) with gentle agitation for 30 min at room temperature. Afterward, the gel was equilibrated for 30 min in developing buffer (50 mM Tris-Base, 0.2 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.02% Brij35) and then incubated in fresh developing buffer overnight at 37°C. The zymographic activities were revealed by staining the gel with 0.2% Coomassie Blue. Gels were destained with a destaining solution (7.5% acetic acid in 20% ethanol). Areas of protease activity appeared as clear bands against a dark blue background, where the substrate digestion by the protease occurred. Molecular weights were estimated by comparison with prestained SDS–PAGE markers and a human pro-MMP-2 standard (AnaSpec, USA).

In a different approach, 0.1 μg/ml human pro-MMP-2 (AnaSpec, USA) were mixed with sample buffer and subjected to gelatine zymography as described above. Following electrophoresis, the gel was divided into equal parts, and the individual strips were developed in different developing buffers containing 5 μg/ml CSE, 10 μg/ml CSE, or 1 mM EDTA as positive control, respectively (Albini et al. 2001; Mazzoni et al. 2007).

MMP ELISA

Primary human chondrocytes (n = 3 donors) and SW1353 cells were cultured as described in 12-well plates and pretreated with 5 μg/ml CSE followed by the addition of 10 ng/ml IL1β. After 48 h, the culture supernatants were collected, centrifuged, and stored at −80°C. ELISA assays for MMP-2 and MMP-13 were carried out following the protocols provided by the manufacturer (RayBiotech, USA).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Primary chondrocytes and SW1353 cells were cultured as described in 12-well plates and pretreated for 1 h with 5 μg/ml CSE followed by the addition of 10 ng/ml IL1β. After 6 h, cell monolayers were washed with PBS and total RNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin RNA II Kit (Macherey–Nagel, D) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. On-column DNase digestion was performed for all samples during the isolation process. To quantify and control for the integrity of the isolated RNA preparations, each sample was run on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer Nano LabChip prior to reverse transcription of equal RNA quantities into cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, A). RNA integrity numbers (RINs) were found to range from 7.8 to 10 for all samples.

SYBR green-based RT-qPCR assays for MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9, and MMP-13 as well as TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and TIMP-3 were established according to previously published protocols (Toegel et al. 2007, 2008). Details on primer sequences are given in Table 1. Amplification efficiencies of all primers were evaluated using dilution series of cDNA prepared from chondrocyte mRNA. All RT-qPCR reactions were performed in 25-μl reaction mixtures containing 1 μl cDNA, 12.5 μl SensiMix SYBR Green Master Mix (GenXpress, A), 100 nM primers (Metabion, D), and nuclease-free water to 25 μl and run in duplicate on an Mx3000P QPCR system (Stratagene, USA). Melting curves were generated to confirm a single gene-specific peak and no-template-controls were included in each run to control for contaminations.

The regulation of target genes was calculated as quantities relative to the untreated control group using the MxPro real-time QPCR software, considering both amplification efficiencies and normalization to GAPDH as reference gene. In preceding experiments, the expression stability of 5 candidate reference genes (GAPDH, ACTB, HPRT1, SDHA, B2M) was determined in human chondrocytes and SW1353 cells treated with 5, 10, and 20 μg/ml CSE, as described above. Then, the expression stabilities were evaluated using the geNorm software (Vandesompele et al. 2002), and GAPDH was selected as stable reference gene under the experimental conditions of this study.

We declare that the current study has adhered to the minimal guidelines for the design and documentation of qPCR experiments as recently outlined by Bustin et al. (2010). A qPCR checklist listing all relevant technical information has been provided for the reviewers to assess the technical adequacy of the used qPCR protocols (Supplementary Table 1).

Transfection and reporter assays

The MMP-13 promoter sequence spanning −1007/+27 bp of the human MMP13 promoter was prepared by PCR and cloned into the pGL2-Basic luciferase reporter vector (Promega; USA) as previously described (Ijiri et al. 2005). The expression vectors encoding the NF-kB p50 and p65 subunits were previously described (Grall et al. 2005). The sequences of all constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Transient transfection experiments were carried out in T/C-28a2 cells using LipofectAMINE PLUS™ Reagents (Invitrogen; USA). Cells were seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates and cultured to 80% confluence. Transfections were carried out in serum-free antibiotic-free medium using no more than 325 ng of plasmid DNA, including 300 ng of reporter constructs and 25 ng of expression vectors or pCI empty vector (control). After incubation for 1 h at 37°C with the transfection mixture, cells were treated with 1 ml of serum-free medium containing CSE or caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE; Calbiochem, D) and incubation was continued for 23 h. Cell lysates were prepared using the Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega), and luciferase activities were determined by chemiluminescence assay using the LMaxII384 luminometer (Molecular Devices, USA) and the Luciferase Assay Substrate (Promega). Data are representative of two independent experiments performed in triplicate and expressed as fold change versus control.

Statistics

Data were exported to the GraphPad Prism statistics software package (GraphPad Prism Software, USA). The Gaussian distribution of the data was verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Statistics were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey tests, cross-comparing all study groups (95% confidence interval). P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Cytotoxicity

Aiming to test the potential use of CSE as MMP inhibitor in chondrocytes, we first evaluated the cytotoxic effects of the extract on primary human chondrocytes using an MTT-based viability assay. As shown in Fig. 1, CSE concentrations up to 20 μg/ml did not induce cytotoxicity in chondrocytes, whereas 40 μg/ml CSE significantly reduced viability (47.0 ± 2.2%). In the subsequent assays, therefore, we used the concentrations of CSE below 20 μg/ml.

Cell viability of primary chondrocytes treated with CSE. Serum-starved primary chondrocytes were treated for 72 h with varying concentrations of CSE (up to 40 μg/ml). Cell-viability was evaluated using a MTT-based proliferation assay. The experiment was repeated twice with cells from different donors, and each experimental condition was set up in quadruplicate. Mean values and standard deviations are given with respect to untreated cells (100% viability). *indicates significant differences with respect to untreated controls (P < 0.05)

CSE does not directly modify gelatinolytic activities

Previous work has suggested that MMP-2 is involved in both the physiological collagen turnover in articular cartilage and the matrix degradation in OA cartilage (Duerr et al. 2004). Using gelatin zymography, the present study confirms that chondrocytes isolated from OA cartilage, as well as SW1353 cells (data not shown), express functional pro-MMP-2 (Fig. 2a). In contrast, bands corresponding to MMP-9 activity were hardly detectable (data not shown), reflecting the differences in MMP-2 and MMP-9 mRNA levels (Table 2). The images also indicate that the activity of MMP2 was not affected in primary chondrocytes treated with 5 μg/ml CSE (Fig. 2a). Similarly, when added to the buffer during zymography development, CSE did not substantially affect the enzymatic activity of recombinant MMP-2, whereas the addition of EDTA completely abrogated the gelatinolytic activity (Fig. 2b).

CSE does not directly interfere with the gelatinolytic activity of MMP-2. a Cell culture supernatants of primary chondrocytes isolated from 2 patients (PC1 and PC2) were treated and subjected to gelatine zymography as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1 shows the activity of a recombinant human pro-MMP-2. Lanes 2 and 4 show the supernatants of untreated chondrocytes, whereas lanes 3 and 5 present the supernatants of the chondrocytes treated with 5 μg/ml CSE, respectively. b Recombinant human pro-MMP-2 was subjected to gelatine zymography and developed separately in different developing buffers containing 5 μg/ml CSE, 10 μg/ml CSE or 1 mM EDTA

CSE inhibits IL1β -stimulated production of MMP-13

In order to investigate the effect of CSE on MMP-13 and MMP-2 protein levels produced by human chondrocytes, supernatants of treated cell cultures were collected and subjected to ELISA. We observed that neither IL1β nor CSE significantly modified the expression of MMP-2 in primary or SW1353 cells (data not shown). In contrast, MMP-13 levels were significantly up-regulated in both SW1353 and primary cells after treatment with IL1β (Fig. 3). Pretreatment of SW1353 cells with 5 μg/ml CSE significantly reduced IL1β-stimulated MMP-13 production from 6.7 ± 1.6 to 2.5 ± 1.4 pg/ml, which was comparable to the levels found in untreated cells (1.2 ± 0.5 pg/ml; P > 0.05). In primary chondrocytes, CSE significantly reduced IL1β-stimulated MMP-13 levels from 16.3 ± 1.4 to 13.1 ± 2.7 pg/ml (P < 0.05; n = 3 donors).

CSE inhibits IL1β-stimulated MMP-13 production in human chondrocytes. Primary chondrocytes (PC) were isolated from 3 donors and cultured and analyzed separately. Serum-starved SW1353 cells and PC were pretreated with 5 μg/ml CSE followed by the coincubation with 10 ng/ml IL1β for 48 h. MMP-13 concentration was determined in the cell culture supernatants using ELISA. Mean values and standard deviations from 2 independent experiments (SW1353) and from 3 donors (PC) are given. *indicates significant differences with respect to cells treated with IL1β only (P < 0.05). #indicates significant differences with respect to untreated controls (P < 0.05)

CSE inhibits gene expression of MMPs, but not of TIMPs

To evaluate the effects of CSE on MMP and TIMP expression in human chondrocytes, mRNA levels of 7 MMPs (MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-13) and 3 TIMPs (TIMP-1, TIMP-2, TIMP-3) were quantified using RT-qPCR (Table 2). In agreement with previous reports (Fan et al. 2005), MMP-3 was the most abundant (12.1 ± 12.2 molecules/molecules GAPDH) of the MMPs analyzed in human OA primary chondrocytes, with MMP-7 and MMP-8 showing the lower expression levels. The expression levels of TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and TIMP-3 were relatively higher compared with most MMPs, with lower expression of TIMP-3 (Table 2). Interestingly, the SW1353 cell line showed a different MMP and TIMP expression profile as compared to primary cells (Table 2), with MMP-2 being the most abundant (0.22 molecules/molecule GAPDH) and very low levels of MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-13 mRNA.

IL1β up-regulated the expression of a number of MMPs in SW1353 cells, including MMP-1 (Fig. 4a, 64.0 ± 3.1 fold), MMP-3 (Fig. 4c, 27.4 ± 0.8 fold), MMP-7 (Fig. 4d, 3.2 ± 0.1 fold), MMP-8 (Fig. 4e, 6.3 ± 1.1 fold), MMP-9 (Fig. 4f, 1.8 ± 0.1 fold), and MMP-13 (Fig. 4g, 71.4 ± 1.1 fold). Preincubation of SW1353 cells with CSE suppressed the IL1β-induced mRNA levels of these MMPs in a dose-dependent manner. Of note, 5 μg/ml CSE strongly inhibited the expression of MMP-1 (Fig. 4a), MMP-3 (Fig. 4c), and MMP-13 (Fig. 4g) mRNA as compared to IL1β-treated cells (P < 0.05), and 10 μg/ml CSE further down-regulated the expression of these genes to levels comparable to control cells (P > 0.05). In addition, 5 μg/ml of CSE reduced the IL-1β-induced MMP-7 (Fig. 4d), MMP-8 (Fig. 4e), and MMP-9 (Fig. 4f) expression to basal levels. Regarding MMP-2 gene expression, no alterations were observed in SW1353 cells under the experimental conditions of this study (Fig. 4b).

CSE inhibits IL1β-mediated MMP transcription in SW1353 cells. Serum-starved SW1353 cells were pretreated with 5, 10, or 20 μg/ml of CSE followed by the addition of 10 ng/ml IL1β. After 6 h of incubation, total RNA was isolated and mRNA levels of a MMP-1, b MMP-2, c MMP-3, d MMP-7, e MMP-8, f MMP-9, and g MMP-13 were quantified using RT-qPCR and expressed as fold change with respect to untreated controls. Mean values and standard deviations are given. *indicates significant differences with respect to cells treated with IL1β only (P < 0.05). #indicates significant differences with respect to untreated controls (P < 0.05)

In keeping with those observations, the results obtained with human OA primary chondrocytes (n = 3; PC1,2,3) further confirmed those obtained in SW1353 cells, as shown in Table 3. Namely, despite minor inter-individual differences, IL1β significantly increased mRNA levels of MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-13 in all 3 cell populations. At 5 μg/ml, CSE significantly suppressed the IL1β-mediated upregulation of MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-13 in all cell populations and that of MMP-1 in 2 out of 3 donors. Similar to the results in SW1353 cells, 10 and 20 μg/ml CSE reduced the IL-1β-induced MMP mRNA expression to basal levels. Expression of MMP-2 and MMP-8 were only slightly altered in the presence of IL1β and CSE (P < 0.05 in 1 out of 3 donors).

Since the balance between MMP and TIMP activities determines cartilage degradation in OA [Nagase and Woessner 1999), we examined the effect of 5 μg/ml CSE on the gene expression of TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and TIMP-3 in IL1β-treated chondrocytes (Fig. 5). In primary cells, neither IL1β nor 5 μg/ml CSE regulated the mRNA levels of any of the TIMPs (Fig. 5a, b, c). In SW1353 cells, however, TIMP-1 and TIMP-3 mRNA levels were up-regulated by IL1β 2.1 ± 0.3 fold and 3.0 ± 0.1 fold, respectively. Treatment with 5 μg/ml CSE reduced only TIMP-3 mRNA levels significantly in SW1353 cells (Fig. 5d).

Regulation of TIMP transcription by IL1β and CSE in SW1353 cells and primary chondrocytes. a–c Primary chondrocytes were isolated from 3 donors (PC1, PC2, PC3) and cultured and analyzed separately. Serum-starved cells were pretreated with 5 μg/ml CSE followed by the addition of 10 ng/ml IL1β. After 6 h of incubation, the mRNA levels of TIMP-1 (a), TIMP-2 (b), and TIMP-3 (c) were quantified using RT-qPCR and expressed as fold change with respect to untreated controls (white bars). Gray bars represent IL1β-treated cells, whereas black bars represent cells pretreated with CSE. d TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and TIMP-3 mRNA levels were quantified in SW1353 cells under exposure to IL1β and CSE as described. Mean values and standard deviations are given. *indicates significant differences with respect to cells treated with IL1β only (P < 0.05). #indicates significant differences with respect to untreated controls (P < 0.05)

These results suggest that CSE is a potent inhibitor of IL1β-mediated MMP transcription in human chondrocytes, whereas it appears not to interfere with TIMP gene expression.

CSE inhibits MMP-13 promoter activation

It has been shown that IL1β-induced MMP gene expression is mediated by diverse signaling pathways and transcription factors, including NF-kB (Vincenti and Brinckerhoff 2002; Marcu et al. 2010). To further explore the mechanism underlying suppression of MMP transcription by CSE, human T/C-28a2 chondrocytes were co-transfected with a MMP-13 reporter construct and p65/p50 expression vectors in the presence or absence of CSE. As shown in Fig. 6, p65/p50 overexpression transactivated the pGL2B(−1007/+27)MMP-13 construct by 7.1 ± 1.5 fold, and CSE reversed the p65/p50-driven MMP-13 promoter transactivation in a concentration-dependent manner. Whereas 5 μg/ml CSE significantly inhibited MMP-13 promoter activity by about 65%, 10 μg/ml CSE completely blocked the p65/p50-mediated promoter activation, re-establishing levels comparable to those in the untreated control (P > 0.05).

Effect of CSE or CAPE on MMP-13 promoter activity. T/C28a2 chondrocytes, cotransfected with a MMP-13 luciferase reporter construct and p50 and p65 expression vectors, were treated with CAPE (gray bars) or CSE (black bars) in a dose-dependent manner. Both CAPE and CES inhibited the NF-kB(p65/p50)-driven MMP-13 promoter activation. #indicates significant differences with respect to cells transfected with the MMP-13 reporter construct and the pCI empty vector (P < 0.05). *indicates significant differences with respect to cells co-transfected with the MMP-13 promoter and the p65/p50 expression vectors (P < 0.05)

For comparison, additional experiments using CAPE were performed (Fig. 6). CAPE dose-dependently reduced the p65/p50-dependent promoter activation at a concentration of 0.5 μg/ml (P < 0.05) and re-established control levels at 2.5 μg/ml.

Discussion

The present study shows for the first time that CSE inhibits MMP expression in human chondrocytes in vitro. As our data demonstrate, pretreatment of primary chondrocytes with CSE effectively suppressed the IL1β-mediated upregulation of MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-13 at the level of gene expression involving NFkB signaling.

Since exacerbated production and activation of MMPs is associated with rheumatoid arthritis and OA, MMPs represent promising pharmacological targets for the treatment of arthritic diseases (Jacobsen et al. 2010). Strategies for MMP inhibition include direct MMP inhibition (by TIMPs, small molecule MMP inhibitors, or antibodies) and indirect MMP inhibition targeting signaling pathways that lead to MMP expression. Although considerable progress has been made in the development of direct MMP inhibitors, severe off-target effects, poor bioavailability and efficacy are frequently associated with their use in clinical trials (Clutterbuck et al. 2009). Thus, indirect MMP inhibition using nutraceuticals or plant-derived phytopharmaceuticals might provide a promising alternative to present therapeutic approaches. In this context, curcumin, resveratrol, or green tea catechins have already been investigated regarding their MMP-inhibitory actions (Shakibaei et al. 2007; Lee and Moon 2005; Annabi et al. 2007).

The results presented here suggest that Caesalpinia sappan-derived phytochemicals might be developed as nutraceuticals for the management of arthritic diseases. In this context, the strong inhibitory action of CSE on the IL1β-mediated overexpression of MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-13 appears of particular interest. Exacerbated production and activation of the collagenases, MMP-1 and MMP-13, in articular chondrocytes are known to promote the cleavage of collagen triple helices allowing further degradation by other MMPs (Nagase and Woessner 1999). Supporting the role of MMP-13 in connective tissue degradation, Neuhold et al. (2001) reported that transgenic mice overexpressing MMP-13 show signs of articular cartilage degradation and exhibit joint pathology similar to that found in OA. Our results confirm that IL1β represents a potent inflammatory stimulus that leads to overexpression of MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-13 mRNA in primary and SW1353 chondrocytes. Interestingly, the upregulation of these genes by IL1β was more pronounced in SW1353 cells than in primary OA chondrocytes; however, when cultured in the presence of 5–20 μg/ml CSE, the effect of IL1β was suppressed in both cell models and the expression of MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-13 mRNA was down-regulated to levels found under control conditions. The relevance of the RT-qPCR data was further verified by ELISA, demonstrating reduced MMP-13 protein levels in chondrocytes treated with CSE. In contrast, however, the transcription of TIMPs was not affected by the presence of CSE. Of note, CSE treatment did not totally block the expression of MMPs but rather inhibited IL1β-induced MMP overexpression. In this regard, CSE might be advantageous over other MMP inhibitors, since total MMP inhibition not only impairs physiological ECM remodeling, but may also affect cellular signaling to which MMPs contribute (Clutterbuck et al. 2009). In this context, it is noteworthy that CSE did not directly influence the gelatinolytic activity of MMP-2 under the experimental conditions of this study.

In a first attempt to elaborate the mechanism underlying the MMP-inhibitory action of CSE, we focused on the role of NF-kB in MMP-13 promoter activation. It is well established that IL1β, once bound to its type 1 receptor, activates NF-kB dimers by triggering phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of the inhibitory kB proteins (Daheshia and Yao 2008). The most prevalent activated NF-kB dimer is the heterodimer RelA (p65)/p50, which can bind to sites in NF-kB-dependent promoters regulating the transcription of response genes (Roman-Blas and Jimenez 2006). Mengshol et al. have assessed the role of NF-kB in MMP-13 transcription in chondrocytes and found that, besides JNK and p38, NF-kB signaling is required for the IL1β-mediated induction of MMP-13 (Mengshol et al. 2000). Although the promoter of MMP-13 does not contain consensus NF-kB binding sites (Burrage et al. 2006), the link between NF-kB activation and MMP-13 induction has been further demonstrated in a previous study on the effect of hyaluronan oligosaccharides in articular chondrocytes (Ohno et al. 2006). We show here that, indeed, NF-kB p65/p50 overexpression leads to MMP-13 promoter transactivation and that CSE suppresses the p65/p50-driven MMP-13 promoter activation, thereby suggesting that CSE’s MMP-inhibitory actions are related to its blockade of the NF-kB signaling. Furthermore, the comparison to CAPE, a chemically defined specific inhibitor of NF-kB (Natarajan et al. 1996), revealed that CSE was only about 4 times less active in our assay. Our results go along with previous reports demonstrating that CSE and its constituents interfere with NF-kB signaling in different cell types. Namely, Bae et al. (2005) showed that brazilin, the main component of CSE, inhibited the DNA binding activity of NF-kB and AP-1 in LPS-stimulated mouse macrophages. In addition, protosappanin A was shown to target the NF-kB pathway in rat heart tissue (Wu et al. 2010). Therefore, our results suggest that CSE contains one or more active components that may act as potent inhibitors of NF-kB in human chondrocytes.

To date, the bioavailability of specific components of CSE has not been elaborated and it remains elusive whether the doses of CSE used in this study are representative for physiologically active concentrations. Despite this lack of specific knowledge, the efficacy of CSE in diverse in vivo models supports the apparent bioavailability of CSE components at therapeutically effective doses (Sun et al. 2011; Oh et al. 2001). Moreover, the present study demonstrates that CSE affects human chondrocytes in vitro at concentrations that are comparable to those of well-known dietary antioxidants including ascorbic acid, curcumin, or resveratrol (Csaki et al. 2009; Graeser et al. 2009). Similar to curcumin and resveratrol, CSE appears to exert its effects on chondrocytes via mechanisms targeting NFkB signaling. Interestingly, recent data have explored the different molecular targets of curcumin and resveratrol as well as their synergistic chondroprotective effects (Csaki et al. 2009). In this context, it might be of interest to further investigate the synergism between CSE components and other dietary antioxidants regarding the modulation of biomarkers of inflammation in cultured chondrocytes.

Conclusion

In summary, this study suggests that CSE or CSE-derived compounds may be beneficial as indirect MMP inhibitors for the future management of degenerative or inflammatory joint diseases. We present evidence that CSE effectively suppresses IL1β-mediated overexpression of major MMPs in human chondrocytes in vitro. More specifically, CSE inhibits the de novo synthesis of MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-13 at the gene expression level without affecting the expression of TIMPs. Further, we showed that the molecular mechanism underlying MMP-13 inhibition by CSE involves, at least in part, the interference with the NF-kB (p65/p50)-driven MMP-13 promoter transactivation. Future studies should therefore aim to define CSE’s actions in the context of arthritic diseases and to further delineate the molecular mechanisms evoked by CSE and its specific constituents both in vitro and in vivo.

References

Albini A, Morini M, D’Agostini F, Ferrari N, Campelli F, Arena G, Noonan DM, Pesce C, De Flora S (2001) Inhibition of angiogenesis-driven Kaposi’s sarcoma tumor growth in nude mice by oral N-acetylcysteine. Cancer Res 61:8171–8178

Ameye LG, Chee WSS (2006) Osteoarthritis and nutrition. From nutraceuticals to functional foods: a systematic review of the scientific evidence. Arthr Res Ther 8:R127

Annabi B, Currie JC, Moghrabi A, Béliveau R (2007) Inhibition of HuR and MMP-9 expression in macrophage-differentiated HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells by green tea polyphenol EGCg. Leuk Res 31:1277–1284

Bae IK, Min HY, Han AR, Seo EK, Lee SK (2005) Suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase by brazilin in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Eur J Pharmacol 513:237–242

Bjorkman DJ (1999) Current status of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use in the United States: risk factors and frequency of complications. Am J Med 107:3S–8S

Burrage PS, Mix KS, Brinckerhoff CE (2006) Matrix metalloproteinases: role in arthritis. Front Biosci 11:529–543

Bustin SA, Beaulieu JF, Huggett J, Jaggi R, Kibenge FSB, Olsvik PA, Penning LC, Toegel S (2010) MIQE précis: practical implementation of minimum standard guidelines for fluorescence-based quantitative real-time PCR experiments. BMC Mol Biol 11:74

Chen YP, Liu L, Zhou YH, Wen J, Jiang Y, Tu PF (2008) Chemical constituents from Sappan Lignum. J Chin Pharm Sci 17:82–86

China pharmacopoeia commission (2010) The Chinese Pharmacopoeia. Medical science press, Beijing

Clutterbuck AL, Asplin KE, Harris P, Allaway D, Mobasheri A (2009) Targeting matrix metalloproteinases in inflammatory conditions. Curr Drug Targets 10:1245–1254

Csaki C, Mobasheri A, Shakibaei M (2009) Synergistic chondroprotective effects of curcumin and resveratrol in human articular chondrocytes: inhibition of IL-1beta-induced NF-kappaB-mediated inflammation and apoptosis. Arthr Res Ther 11:R165

Daheshia M, Yao JQ (2008) The interleukin 1beta pathway in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 35:2306–2312

Duerr S, Stremme S, Soeder S, Bau B, Aigner T (2004) MMP-2/gelatinase A is a gene product of human adult articular chondrocytes and is increased in osteoarthritic cartilage. Clin Exp Rheumatol 22:603–608

Fan Z, Bau B, Yang H, Soeder S, Aigner T (2005) Freshly isolated osteoarthritic chondrocytes are catabolically more active than normal chondrocytes, but less responsive to catabolic stimulation with interleukin-1β. Arthr Rheum 52:136–143

Goggs R, Vaughan-Thomas A, Clegg PD, Carter SD, Innes JF, Mobasheri A, Shakibaei M, Schwab W, Bondy CA (2005) Nutraceutical therapies for degenerative joint diseases: a critical review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 45:145–164

Goldring MB, Marcu KB (2009) Cartilage homeostasis in health and rheumatic diseases. Arthr Res Ther 11:224

Goldring MB, Otero M, Tsuchimochi K, Ijiri K, Li Y (2008) Defining the roles of inflammatory and anabolic cytokines in cartilage metabolism. Ann Rheum Dis 67:75–82

Graeser AC, Giller K, Wiegand H, Barella L, Boesch Saadatmandi C, Rimbach G (2009) Synergistic chondroprotective effect of alpha-tocopherol, ascorbic acid, and selenium as well as glucosamine and chondroitin on oxidant induced cell death and inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-3—studies in cultured chondrocytes. Molecules 15:27–39

Grall FT, Prall WC, Wei W, Gu X, Cho JY, Choy BK, Zerbini LF, Inan MS, Goldring SR, Gravallese EM, Goldring MB, Oettgen P, Libermann TA (2005) The Ets transcription factor ESE-1 mediates induction of the COX-2 gene by LPS in monocytes. FEBS J 272:1676–1687

Ijiri K, Zerbini LF, Peng H, Correa RG, Lu B, Walsh N, Zhao Y, Taniguchi N, Huang XL, Otu H, Wang H, Wang JF, Komiya S, Ducy P, Rahman MU, Flavell RA, Gravallese EM, Oettgen P, Libermann TA, Goldring MB (2005) A novel role for GADD45beta as a mediator of MMP-13 gene expression during chondrocyte terminal differentiation. J Biol Chem 280:38544–38555

Jacobsen JA, Major Jourden JL, Miller MT, Cohen SM (2010) To bind zinc or not to bind zinc: an examination of innovative approaches to improved metalloproteinase inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta 1803:72–94

Jeong IY, Chang HJ, Park YD, Lee HJ, Choi DS, Byun MW, Kim YJ (2008) Anti-inflammatory activity of an ethanol extract of Caesalpinia sappan L. in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. J Food Sci Nutr 13:253–258

Kubota E, Imamura H, Kubota T, Shibata T, Murakami K (1997) Interleukin 1 beta and stromelysin (MMP3) activity of synovial fluid as possible markers of osteoarthritis in the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 55:20–27

Lee B, Moon SK (2005) Resveratrol inhibits TNF-alpha-induced proliferation and matrix metalloproteinase expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Nutr 135:2767–2773

Little CB, Barai A, Burkhardt D, Smith SM, Fosang AJ, Werb Z, Shah M, Thompson EW (2009) Matrix metalloproteinase 13-deficient mice are resistant to osteoarthritic cartilage erosion but not chondrocyte hypertrophy or osteophyte development. Arthr Rheum 60:3723–3733

Marcu KB, Otero M, Olivotto E, Borzi RM, Goldring MB (2010) NF-kappaB signaling: multiple angles to target OA. Curr Drug Targets 11:599–613

Mazzoni A, Mannello F, Tay FR, Tonti GA, Papa S, Mazzotti G, Di Lenarda R, Pashley DH, Breschi L (2007) Zymographic analysis and characterization of MMP-2 and -9 forms in human sound dentin. J Dent Res 86:436–440

Mengshol JA, Vincenti MP, Coon CI, Barchowsky A, Brinckerhoff CE (2000) Interleukin-1 induction of collagenase 3 (matrix metalloproteinase 13) gene expression in chondrocytes requires p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and nuclear factor kappa B: differential regulation of collagenase 1 and collagenase 3. Arthr Rheum 43:801–811

Mix KS, Mengshol JA, Benbow U, Vincenti MP, Sporn MB, Brinckerhoff CE (2001) A synthetic triterpenoid selectively inhibits the induction of matrix metalloproteinases 1 and 13 by inflammatory cytokines. Arthr Rheum 44:1096–1104

Nagase H, Woessner JF (1999) Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem 274:21491–21494

Natarajan K, Singh S, Burke TR Jr, Grunberger D, Aggarwal BB (1996) Caffeic acid phenethyl ester is a potent and specific inhibitor of activation of nuclear transcription factor NF-kappa B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:9090–9095

Neuhold LA, Killar L, Zhao W, Sung ML, Warner L, Kulik J, Turner J, Wu W, Billinghurst C, Meijers T, Poole AR, Babij P, DeGennaro LJ (2001) Postnatal expression in hyaline cartilage of constitutively active human collagenase-3 (MMP-13) induces osteoarthritis in mice. J Clin Invest 107:35–44

Oh GT, Choi JH, Hong JJ, Kim DY, Lee SB, Kim JR, Lee CH, Hyun BH, Oh SR, Bok SH, Jeong TS (2001) Dietary hematein ameliorates fatty streak lesions in the rabbit by the possible mechanism of reducing VCAM-1 and MCP-1 expression. Atherosclerosis 159:17–26

Ohno S, Im HJ, Knudson CB, Knudson W (2006) Hyaluronan oligosaccharides induce matrix metalloproteinase 13 via transcriptional activation of NFkappaB and p38 MAP kinase in articular chondrocytes. J Biol Chem 281:17952–17960

Roman-Blas JA, Jimenez SA (2006) NF-kB as a potential therapeutic target in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 14:839–848

Saha N, Moldovan F, Tardif G, Pelletier JP, Cloutier JM, Martel-Pelletier J (1999) Interleukin-1-β-converting enzyme/caspase-1 in human osteoarthritic tissues: localization and role in the maturation of interleukin-1β and interleukin-18. Arthr Rheum 42:1577–1587

Shakibaei M, John T, Schulze-Tanzil G, Lehmann I, Mobasheri A (2007) Suppression of NF-kappaB activation by curcumin leads to inhibition of expression of cyclo-oxygenase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in human articular chondrocytes: implications for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Biochem Pharmacol 73:1434–1445

Sireeratawong S, Piyabhan P, Singhalak T, Wongkrajang Y, Temsiririrkkul R, Punsrirat J, Ruangwises N, Saraya S, Lerdvuthisopon N, Jaijoy K (2010) Toxicity evaluation of sappan wood extract in rats. J Med Assoc Thai 93:S50–S57

Smith MD, Triantafillou S, Parker A, Youssef PP, Coleman M (1997) Synovial membrane inflammation and cytokine production in patients with early osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 24:365–371

Srilakshmi VS, Vijayan P, Raj PV, Dhanaraj SA, Chandrashekhar HR (2010) Hepatoprotective properties of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood on carbon tetrachloride induced toxicity. Indian J Exp Biol 48:905–910

Sun SQ, Wang YZ, Zhou YB (2011) Extract of the dried heartwood of Caesalpinia sappan L. attenuates collagen-induced arthritis. J Ethnopharmacol Article, in press

Tetlow LC, Adlam DJ, Woolley DE (2001) Matrix metalloproteinase and proinflammatory cytokine production by chondrocytes of human osteoarthritic cartilage: associations with degenerative changes. Arthr Rheum 44:585–594

The Society of Japanese Pharmacopoeia (2006) The Japanese Pharmacopoeia, 15th edn. Hirokawa Publishing, Tokyo

Toegel S, Huang W, Piana C, Unger FM, Wirth M, Goldring MB, Gabor F, Viernstein H (2007) Selection of reliable reference genes for qPCR studies on chondroprotective action. BMC Mol Biol 8:13

Toegel S, Wu SQ, Piana C, Unger FM, Wirth M, Goldring MB, Gabor F, Viernstein H (2008) Comparison between chondroprotective effects of glucosamine, curcumin, and diacerein in IL-1β stimulated C-28/I2 chondrocytes. Osteoarthr Cartil 16:1205–1212

Toegel S, Plattner VE, Wu SQ, Chiari C, Gabor F, Unger FM, Goldring MB, Nehrer S, Viernstein H, Wirth M (2009) Lectin binding patterns reflect the phenotypic status of in vitro chondrocyte models. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 45:351–360

Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F (2002) Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol 18:3

Vincenti MP, Brinckerhoff CE (2002) Transcriptional regulation of collagenase (MMP-1, MMP-13) genes in arthritis: integration of complex signaling pathways for the recruitment of gene-specific transcription factors. Arthr Res 4:157–164

Washiyama M, Sasaki Y, Hosokawa T, Nagumo S (2009) Anti-inflammatory constituents of Sappan Lignum. Biol Pharm Bull 32:941–944

Wu J, Zhang M, Jia H, Huang X, Zhang Q, Hou J, Bo Y (2010) Protosappanin A induces immunosuppression of rats heart transplantation targeting T cells in grafts via NF-kappaB pathway. Naunyn Schmied Arch Pharmacol 381:83–92

Xie YW, Ming DS, Xu HX, Dong H, But PP (2000) Vasorelaxing effects of Caesalpinia sappan involvement of endogenous nitric oxide. Life Sci 67:1913–1918

Ye M, Xie WD, Lei F, Meng Z, Zhao YN, Su H, Du LJ (2006) Brazilein, an important immunosuppressive component from Caesalpinia sappan L. Int Immunopharmacol 6:426–432

Acknowledgments

This research was supported partially by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01-AG022021 (Mary B Goldring), an Arthritis Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (Miguel Otero), and the graduate program “Molecular Drug Targets” sponsored by the University of Vienna (Shengqian Q Wu).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12263_2011_244_MOESM1_ESM.jpg

HPLC analysis. CSE was prepared and subjected to HPLC analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Panel (A) shows the HPLC chromatogram of CSE at 280 nm, whereas panel (B) shows the chromatogram of Natural Red 24 (MP Biomedicals, USA, LOT #: R25179) analyzed under the same conditions as CSE. Both chromatograms are characterized by two major peaks at retention times of 13.4 min and 15.9 min, respectively. (JPEG 2489 kb)

12263_2011_244_MOESM2_ESM.xls

qPCR checklist with all relevant technical information of the RT-qPCR protocols used in the present study. This information aims to provide transparency of the design, performance and documentation of qPCR experiments as recently outlined by Bustin et al. [2010]. (XLS 43 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toegel, S., Wu, S.Q., Otero, M. et al. Caesalpinia sappan extract inhibits IL1β-mediated overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases in human chondrocytes. Genes Nutr 7, 307–318 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-011-0244-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-011-0244-8