Abstract

Introduction

Over a million Americans have survived colorectal cancer. This study examined physician visit patterns, patient comorbidities, and mammography use among colorectal cancer survivors based on the competing demands model.

Methods

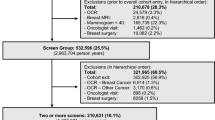

Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare linked data (2003 merge), study cohorts included female colorectal cancer patients who were diagnosed from 1973 through 1994 and had survived five or more years after the cancer diagnosis (n = 12,681), and a non-cancer comparison population who had no history of cancer and resided in the SEER areas during the study period.

Results

Cancer survivors had a significant 6% higher mammography rate during 2000 to 2001 than matched women with no history of cancer (50 vs 47 per 100 persons, respectively). Among cancer survivors, there was a significant and positive association between the number of physician visits for evaluation and management (E&M) and mammography rates. More physician visits for E&M reduced the differences of mammography rates between those with and without additional comorbidities. Cancer survivors who visited gynecologists for E&M were 45% more likely to receive mammograms than those who visited only primary care physicians (multivariate adjusted rate ratio, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.38–1.53).

Conclusions

Elderly female colorectal cancer survivors were more likely to receive mammograms than matched women with no history of cancer.

Implications for cancer survivors

Patients with multiple comorbidities might receive more mammograms by increasing the number of office visits for E&M and by visiting gynecologists. Primary care physicians should increase the priority for recommending mammograms among cancer survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ries LAG MD, Krapcho M, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Clegg L, Horner MJ, Howlader N, Eisner MP, Reichman M, Edwards BK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2004, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004/. Accessed 9 July 2007.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer Survivorship—United States, 1971–2001. MMWR. June 25, 2004/53(24);526–29.

Travis LB, Fossa SD, Schonfeld SJ, McMaster ML, Lynch CF, Storm H, et al. Second cancers among 40,576 testicular cancer patients: focus on long-term survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:1354–65.

Kirchhoff T, Satagopan JM, Kauff ND, Huang H, Kolachana P, Palmer C, et al. Frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in unselected Ashkenazi Jewish patients with colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:68–70.

Feuer EJ, Wun LM. Devcan: probability of developing or dying of cancer, version 4.0. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1999.

Trask PC, Rabin C, Rogers ML, Whiteley J, Nash J, Frierson G, et al. Cancer screening practices among cancer survivors. Am J Prev Med 2005;28:351–6.

Wallace AE, MacKenzie TA, Weeks WB. Women’s primary care providers and breast cancer screening: who’s following the guidelines? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:744–8.

Earle CC, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Weeks JC. Quality of non-breast cancer health maintenance among elderly breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1447–51.

Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer 2004;101:1712–9.

McBean MA, Yu X, Virnig BA. Preventive services use among uterine cancer survivors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008 (in press).

Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:8884–93.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

Jaen CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract 1994;38:166–71.

Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003;58:82–91.

Fox SA, Siu AL, Stein JA. The importance of physician communication on breast cancer screening of older women. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:2058–68.

Bynum JP, Braunstein JB, Sharkey P, Haddad K, Wu AW. The influence of health status, age, and race on screening mammography in elderly women. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:2083–8.

Anonymous. Screening mammography: a missed clinical opportunity? Results of the NCI breast cancer screening consortium and national health interview survey studies. JAMA 1990;264:54–8.

Taplin SH, Urban N, Taylor VM, Savarino J. Conflicting national recommendations and the use of screening mammography: does the physician’s recommendation matter? J Am Board Fam Pract 1997;10:88–95.

Cummings DM, Whetstone L, Shende A, Weismiller D. Predictors of screening mammography: implications for office practice. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:870–5.

Harrold LR, Field TS, Gurwitz JH. Knowledge, patterns of care, and outcomes of care for generalists and specialists. J Gen Intern Med 1999;14:499–511.

Smetana GW, Landon BE, Bindman AB, Burstin H, Davis RB, Tjia J, et al. A comparison of outcomes resulting from generalist vs specialist care for a single discrete medical condition: a systematic review and methodologic critique. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:10–20.

Kiefe CI, Funkhouser E, Fouad MN, May DS. Chronic disease as a barrier to breast and cervical cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:357–65.

Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER–Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care 2002;40:IV–3–18.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–9.

Klabunde CN, Harlan LC, Warren JL. Data sources for measuring comorbidity: a comparison of hospital records and Medicare claims for cancer patients. Med Care 2006;44:921–8.

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27.

Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:757–63.

Leuven E, Sianesi B. Psmatch2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html. Accessed in 9 July 2007.

Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6.

Mandelblatt J, Saha S, Teutsch S, Hoerger T, Siu AL, Atkins D, et al. The cost-effectiveness of screening mammography beyond age 65 years: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:835–42.

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2006. With chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD; 2006.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

Nutting PA, Baier M, Werner JJ, Cutter G, Conry C, Stewart L. Competing demands in the office visit: what influences mammography recommendations? J Am Board Fam Pract 2001;14:352–61.

Stange KC, Fedirko T, Zyzanski SJ, Jaen CR. How do family physicians prioritize delivery of multiple preventive services? J Fam Pract 1994;38:231–7.

Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health 2003;93:635–41.

Van Harrison R, Janz NK, Wolfe RA, Tedeschi PJ, Stross JK, Huang X, et al. Characteristics of primary care physicians and their practices associated with mammography rates for older women. Cancer 2003;98:1811–21.

Fortney JC, Steffick DE, Burgess JF Jr., Maciejewski ML, Petersen LA. Are primary care services a substitute or complement for specialty and inpatient services? Health Serv Res 2005;40:1422–42.

McBean AM, Yu X. The underuse of screening services among elderly women with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1466–72.

Wennberg JE. On patient need, equity, supplier-induced demand, and the need to assess the outcome of common medical practices. Med Care 1985;23:512–20.

Acknowledgement

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Aging (R01 AG 025079) and the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA 098974).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, X., McBean, A.M. & Virnig, B.A. Physician visits, patient comorbidities, and mammography use among elderly colorectal cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 1, 275–282 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-007-0037-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-007-0037-7