Abstract

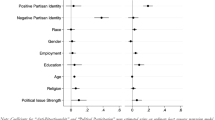

We examine the associations between personality traits and the strength and direction of partisan identification using a large national sample. We theorize that the relationships between Big Five personality traits and which party a person affiliates with should mirror those between the Big Five and ideology, which we find to be the case. This suggests that the associations between the Big Five and the direction of partisan identification are largely mediated by ideology. Our more novel finding is that personality traits substantially affect whether individuals affiliate with any party as well as the strength of those affiliations, effects that we theorize stem from affective and cognitive benefits of affiliation. In particular, we find that three personality traits (Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Openness) predict strength of partisan identification (p < 0.05). This result holds even after controlling for ideology and a variety of issue positions. These findings contribute to our understanding of the psychological antecedents of partisan identification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Scholars have considered some important psychological sources of partisan affiliation. For example, a relative lack of a “partisan social identity” compared to an “independent social identity” helps explain why partisan “leaners” are different from “true” partisans (Greene 2000). However, the present research is unique in that it focuses on dispositional traits, which develop independently of political environments.

For example, Gerber et al. (2010a) find that the relationships between Big Five traits and political attitudes vary across racial groups. Similarly, Mondak et al. (2010) find that the relationships between Big Five traits and political participation depend on characteristics of the political environment. Each of these studies suggests that the attitudinal and behavioral consequences of dispositional traits depend on contextual factors.

Elections in the United States are dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties. In the 2008 U.S. elections, 97.3% of votes cast in House races went to candidates from these parties, and a similar proportion went to candidates in gubernatorial (97.6%), Senate (96.6%), and presidential (98.5%) elections. From 1961 to 2008, politicians from parties other than the two major parties have only served 12 out of the 10,859 representative/terms in the House of Representatives and 5 of approximately 828 senator/terms in the Senate.

Other studies in the U.S. and Europe have examined the associations between Big Five traits and vote choice or vote intention (Barbaranelli et al. 2007; Caprara et al. 1999; Schoen and Schumann 2007) or statewide vote returns (Rentfrow et al. 2009) and find similar relationships. In a German sample, for example, Schoen and Schumann find that those high on Openness and Emotional Stability tend to vote for liberal parties, whereas those high on Conscientiousness and Agreeableness tend to vote for conservative parties. We note that Schoen and Schumann’s finding that Emotional Stability is associated with affiliating with a liberal party conflicts with Mondak and Halperin’s (2008) finding of the inverse relationship.

We have also investigated the direct effects of personality on directional party identification controlling for ideology. We find that once ideology is controlled for, the effects of Big Five personality traits on which party one chooses to identify with are greatly attenuated. See below for further details.

The survey sample is constructed by first drawing a target population sample. This sample is based on the 2005–2007 American Community Study (ACS), November 2008 Current Population Survey Supplement, and the 2007 Pew Religious Life Survey. Thus, this target sample is representative of the general population on a broad range of characteristics including a variety of geographic (state, region, metropolitan statistical area), demographic (age, race, income, education, gender), and other measures (born-again status, employment, interest in news, party identification, ideology, and turnout). Polimetrix invited a sample of their opt-in panel of 1.4 million survey respondents to participate in the study. Invitations were stratified based on race, gender, and battleground status, with an oversample of nine battleground and early primary states (Florida, Iowa, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin). Those who completed the survey (approximately 2.5 times the target sample) were then matched to the target sample using nearest-neighbor matching based on the variables listed in parentheses above. Finally, weights were calculated to adjust the final sample to reflect the national public on these demographic and other characteristics (including correcting for the oversampling of battleground states). For more detailed information on this type of survey and sampling technique see Vavreck and Rivers (2008). In concrete terms, the weighted CCAP sample we use in our analysis appears similar in levels of political interest to that found in the weighted 2008 American National Election Study (ANES) time-series survey. In the September wave of the CCAP we find that 55% of respondents are “very much” interested in politics (variable = scap813, “How interested are you in politics?”). In the ANES pre-election survey, the comparable figure is 58% (variable = V0830001b, “How interested are you in information about what’s going on in government and politics?” = Extremely or very interested, restricted to reported registered voters).

Trait pairs for each trait. Observed correlations in brackets; (R) indicates reverse scoring:

-

Extraversion: Extraverted, enthusiastic; Reserved, quiet (R) [r = 0.432]

-

Agreeableness: Sympathetic, warm; Critical, quarrelsome (R) [r = 0.221]

-

Conscientiousness: Dependable, self-disciplined; Disorganized, careless (R) [r = 0.395]

-

Emotional Stability: Calm, emotionally stable; Anxious, easily upset (R) [r = 0.467]

-

Openness: Open to new experiences, complex; Conventional, uncreative (R) [r = 0.267].

We note that the TIPI was not designed with the intent of achieving high inter-item correlations. Rather, it was designed to (1) be brief; (2) achieve high test–retest reliability (as well as reliability between self- and peer-administered ratings); and (3) yield measures that are highly correlated with those obtained using much longer batteries (the correlations between TIPI measures and the 44-item Big Five Inventory range from 0.65 to 0.87; correlations with measures from the much longer, 240-item NEO PI-R range from 0.56 to 0.68). Therefore, because each question in the TIPI is designed to measure part of a broader Big Five trait, inter-item correlations between the two items used to measure each trait are less informative of the items’ reliability (Gosling 2009; more generally, see Kline 2000; Woods and Hampson 2005 on the misleading nature of alphas calculated on scales with only a small number of items). Table 7 in the Appendix reports sample correlations between the Big Five traits.

-

The inclusion in our analysis of income and education, which unlike gender, age, and race are not immutable characteristics, deserves special attention. We noted above research that finds that personality traits predict these outcomes. However, we believe that including them in the reported analysis is a conservative strategy for two reasons. First, it demonstrates that the effects of personality on the different outcomes we study are not due to the indirect effect of personality on earnings and educational attainment. Second, in practical terms, including income and education in the estimated models tends to yield more conservative estimates of the effect of personality on our outcomes of interest. (Parallel analysis excluding these measures appears in Appendix Tables 8 and 9.) We suppress the education and income indicators from the estimates presented in the body of the text for space reasons. Full results are available upon request.

We have also repeated the analysis in column (1) using a 5-Point Party Identification measure that pools weak and leaning partisans. The results (available upon request) are qualitatively similar to those reported in column (1). This demonstrates that the pattern of results we observe in column (1) is not driven by differences between weak and leaning partisans, whose voting behavior is often quite similar.

We note that this analysis rests on two assumptions. First, we assume that Big Five traits affect directional partisanship through ideology rather than affecting ideology through partisanship. Second, we assume that it is ideology that mediates the relationship between Big Five traits and partisanship rather than an omitted variable that is correlated with ideology, partisanship, and personality.

We conducted additional analysis (available upon request), replacing strength of partisanship with strength of ideology as the dependent variable in the model specification presented in Table 5, column (1). In contrast to the similar relationships between Big Five traits and both ideology and directional partisanship we report in Table 4, we find that the relationships between Big Five traits and strength of ideology are quite different from the relationships between these traits and strength of partisanship. Conscientiousness is positively associated with both of these outcomes; however, the only other statistically significant relationship we find is a positive association between Emotional Stability and strength of ideology, which is in contrast to the negative, but statistically insignificant association between this trait and strength of partisanship.

In more formal tests (available upon request), we conducted Sobel tests to assess whether a linear measure of strength of ideology significantly mediates the relationships between Big Five traits and strength of partisanship. As the findings in Table 5 suggest, including a measure of strength of ideology significantly reduces the magnitude of the coefficient on Conscientiousness. We also find evidence that strength of ideology affects the (statistically insignificant) relationship between Emotional Stability and strength of partisanship. However, in this case the pattern of relationships suggests that excluding strength of ideology from the model suppresses the relationship between these measures (i.e., including the strength of ideology measure strengthens the negative relationship between Emotional Stability and strength of partisanship).

The Tea Party movement emerged following the 2008 general election and is broadly viewed to be ideologically conservative.

The CCES is also administered over the Internet by YouGov/Polimetrix. On the post-election CCES participants were asked: “What is your view of the Tea Party movement—would you say it is very positive, somewhat positive, neutral, somewhat negative, or very negative, or don’t you know enough about the Tea Party movement to say?” (Very Positive; Somewhat Positive; Neutral; Somewhat negative; Very Negative; Don’t know enough to say; No opinion). The analysis reported in Table 10 excludes responses of “don’t know enough to say” and “no opinion”.

The analysis is further restricted by the loss of 31 cases from Washington, DC and Hawaii because no respondents from those areas changed their responses to the party identification question.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., & Saunders, K. L. (1998). Ideological realignment in the U.S. electorate. Journal of Politics, 60, 634–652.

Abramowitz, A. I., & Saunders, K. L. (2006). Exploring the bases of partisanship in the American electorate: Social identity vs. ideology. Political Research Quarterly, 59, 175–187.

Alford, J. R., Funk, C. L., & Hibbing, J. R. (2005). Are political orientations genetically transmitted? American Political Science Review, 99, 153–167.

Alford, J. R., & Hibbing, J. R. (2007). Personal, interpersonal, and political temperaments. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 614, 196–212.

Alwin, D. F., & Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Aging, cohorts, and the stability of sociopolitical orientations over the life span. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 169–195.

Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., Vecchione, M., & Fraley, C. R. (2007). Voters’ personality traits in presidential elections. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 1199–1208.

Borg, M. O., & Shapiro, S. L. (1996). Personality type and student performance in principles of economics. Journal of Economic Education, 27, 3–25.

Borghans, L., Duckworth, A. L., Heckman, J. J., & ter Weel, B. (2008). The economics and psychology of personality traits. Journal of Human Resources, 43, 972–1059.

Bouchard, T. J., Jr. (1997). The genetics of personality. In K. Blum & E. P. Noble (Eds.), Handbook of psychiatric genetics (pp. 273–296). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Brewer, M. B. (1979). In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive motivational analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 17, 475–482.

Brown, R. J., Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1980). Minimal group situations and inter-group discrimination: Comments on the paper by Aschenbrenner and Schaefer. European Journal of Social Psychology, 10, 399–414.

Burden, B. C. (2008). The social roots of the partisan gender gap. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72, 55–75.

Burden, B. C., & Greene, S. (2000). Party attachments and state election laws. Political Research Quarterly, 53, 63–76.

Burden, B. C., & Klofstad, C. A. (2005). Affect and cognition in party identification. Political Psychology, 26, 869–886.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., Miller, W., & Stokes, D. (1960). The American voter. New York: Wiley.

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1999). Personality profiles and political parties. Political Psychology, 20, 175–197.

Carlo, G., Okun, M. A., Knight, G. P., & de Guzman, M. R. T. (2005). The interplay of traits and motives on volunteering: Agreeableness, extraversion and prosocial value motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 1293–1305.

Carney, D. R., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychology, 29, 807–840.

Carsey, T. M., & Layman, G. C. (2006). Changing sides or changing minds? Party. Identification and policy preferences in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 464–477.

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO PI-R. Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Denissen, J. J. A., & Penke, L. (2008). Motivational individual reaction norms underlying the Five-Factor Model of personality: First steps towards a theory-based conceptual framework. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 1285–1302.

Diseth, Å. (2002). Personality and approaches to learning as predictors of academic achievement. European Journal of Personality, 17, 143–155.

Elazar, D. J. (1984). American federalism: A view from the States (3rd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective voting in American national elections. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Fowler, J. H., Baker, L. A., & Dawes, C. T. (2008). Genetic variation in political participation. American Political Science Review, 102, 233–248.

Gerber, A. S., & Huber, G. A. (2009). Partisanship and economic behavior: Do partisan differences in economic forecasts predict real economic behavior? American Political Science Review, 103, 407–426.

Gerber, A. S., & Huber, G. A. (2010). Partisanship, political control, and economic assessments. American Journal of Political Science, 54, 153–173.

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., Dowling, C. M., Raso, C., & Ha, S. E. (2011). Personality traits and participation in political processes. Journal of Politics, 73, 692–706.

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., Dowling, C. M., & Shang, E. H. (2010a). Personality and political attitudes: Relationships across issue domains and political contexts. American Political Science Review, 104, 111–133.

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., & Washington, E. (2010b). Party affiliation, partisanship, and political beliefs: A field experiment. American Political Science Review, 104, 720–744.

Goodwin, R. D., & Friedman, H. S. (2006). Health status and the Five-Factor personality traits in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 643–654.

Goren, P. (2002). Character weakness, partisan bias, and presidential evaluation. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 627–641.

Goren, P. (2005). Party identification and core political values. American Journal of Political Science, 49, 881–896.

Gosling, S. D. (2009). A note on alpha reliability and factor structure in the TIPI. December 20. Accessed January 5, 2010, from http://homepage.psy.utexas.edu/homepage/faculty/gosling/tipi_alpha_note.htm.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504–528.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Greene, S. (1999). Understanding party identification: A social identity approach. Political Psychology, 20, 393–403.

Greene, S. (2000). The psychological sources of partisan-leaning independence. American Politics Research, 28, 511–537.

Greene, S. (2002). The social-psychological measurement of partisanship. Political Behavior, 24, 171–197.

Hatemi, P. K., Alford, J. R., Hibbing, J. R., Martin, N. G., & Eaves, L. J. (2009). Is there a ‘party’ in your genes? Political Research Quarterly, 62, 584–600.

Jackman, S., & Vavreck, L. (2009). Cooperative campaign analysis project, 2007–2008 panel study: Common content. [Computer File] Release 1: February 1, 2009. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA.

Jacoby, W. G. (1988). The impact of party identification on issue attitudes. American Journal of Political Science, 32, 643–661.

Jennings, M. K., & Niemi, R. G. (1974). The political character of adolescence: The influence of families and schools. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press.

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375.

Keith, B. E., Magleby, D. B., Nelson, C. J., Orr, E., Westlye, M. C., & Wolfinger, R. E. (1992). The myth of the independent voter. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Key, V. O., Jr. (1966). The responsible electorate: Rationality in presidential voting 1936–1960. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Key, V. O., Jr., & Munger, F. (1959). Social determinism and electoral decision: The case of Indiana. In E. Burdick & A. Brodbeck (Eds.), American voting behavior (pp. 291–299). Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Kline, P. (2000). Handbook of psychological testing. London: Routledge.

Levendusky, M. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals became democrats and conservatives became republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2000). Three steps toward a theory of motivated political reasoning. In A. Lupia, M. McCubbins, & S. Popkin (Eds.), Elements of political reason: Understanding and expanding the limits of rationality (pp. 183–213). London: Cambridge University Press.

McAdams, D. P., & Pals, J. L. (2006). A new Big Five: Fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality. American Psychologist, 61, 204–217.

McCrae, R. R. (1996). Social consequences of experiential openness. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 323–337.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1996). Toward a new generation of personality theories: Theoretical contexts for the Five-Factor Model. In J. S. Wiggins (Ed.), The Five-Factor Model of personality: Theoretical perspectives (pp. 51–87). New York: The Guilford Press.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory perspective (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Mehrabian, A. (1996). Relations among political attitudes, personality, and psychopathology assessed with new measures of libertarianism and conservatism. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 18, 469–491.

Mondak, J. J. (2010). Personality and the foundations of political behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mondak, J. J., & Halperin, K. D. (2008). A framework for the study of personality and political behaviour. British Journal of Political Science, 38, 335–362.

Mondak, J. J., Hibbing, M. V., Canache, D., Seligson, M. A., & Anderson, M. R. (2010). Personality and civic engagement: An integrative framework for the study of trait effects on political behavior. American Political Science Review, 104, 85–110.

Neuberg, S. L., & Newsom, J. T. (1993). Personal need for structure: Individual differences in the desire for simple structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 113–131.

Niemi, R. G., & Jennings, M. K. (1991). Issues and inheritance in the formation of party identification. American Journal of Political Science, 35, 970–988.

Norrander, B. (1989). Explaining cross-state variation in independent identification. American Journal of Political Science, 33, 516–536.

Norrander, B. (1997). The independence gap and the gender gap. Public Opinion Quarterly, 61, 464–476.

O’Brien, T. P., Bernold, L. E., & Akroyd, D. (1998). Myers-Briggs type indicator and academic achievement in engineering education. International Journal of Engineering Education, 14, 311–315.

Okun, M. A., Pugliese, J., & Rook, K. S. (2007). Unpacking the relation between extraversion and volunteering in later life: The role of social capital. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 1467–1477.

Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., McClearn, G. E., & McGuffin, P. (1990). Behavioral genetics: A primer. New York: W.H. Freeman & Company.

Rahn, W. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37, 472–496.

Redlawsk, D. P. (2002). Hot cognition or cool consideration? Testing the effects of motivated reasoning on political decision making. Journal of Politics, 64, 1021–1044.

Rentfrow, P. J., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2009). Statewide differences in personality predict voting patterns in 1996–2004 U.S. presidential elections. In J. T. Jost, A. C. Kay, & H. Thorisdottir (Eds.), Social and psychological bases of ideology and system justification (pp. 314–347). New York: Oxford University Press.

Riemann, R., Grubich, C., Hempel, S., Mergl, S., & Richter, M. (1993). Personality and attitudes towards current political topics. Personality and Individual Differences, 15, 313–321.

Roberts, B. W., & Bogg, T. (2004). A longitudinal study of the relationships between conscientiousness and the social-environmental factors and substance-use behaviors that influence health. Journal of Personality, 72, 325–354.

Rudolph, T. J. (2003). Who’s responsible for the economy? The formation and consequences of responsibility attributions. American Journal of Political Science, 47, 698–713.

Schaller, M., Boyd, C., Yohannes, J., & O’Brien, M. (1995). The prejudiced personality revisited: Personal need for structure and formation of erroneous group stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 544–555.

Schoen, H., & Schumann, S. (2007). Personality traits, partisan attitudes, and voting behavior. Evidence from Germany. Political Psychology, 28, 471–498.

Settle, J. E., Dawes, C. T., & Fowler, J. H. (2009). The heritability of partisan attachment. Political Research Quarterly, 62, 601–613.

Settles, I. H. (2004). When multiple identities interfere: The role of identity centrality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 487–500.

Srivastava, S., John, O. P., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2003). Development of personality in early and middle adulthood: Set like plaster or persistent change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1041–1053.

Tajfel, H., Flament, C., Billig, M. G., & Bundy, R. F. (1971). Social categorization: An intergroup phenomenon. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1, 149–177.

Turner, J. C. (1991). Social influence. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Van Gestel, S., & Van Broeckhoven, C. (2003). Genetics of personality: Are we making progress? Molecular Psychiatry, 8, 840–852.

Van Hiel, A., Kossowska, M., & Mervielde, I. (2000). The relationship between openness to experience and political ideology. Personality and Individual Differences, 28, 741–751.

Van Hiel, A., & Mervielde, I. (2004). Openness to experience and boundaries in the mind: Relationships with cultural and economic conservative beliefs. Journal of Personality, 72, 659–686.

Van Houweling, R. P., & Sniderman, P. M. (2005). The political logic of a Downsian space. UC Berkeley: Institute of Governmental Studies. http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/3858b03t. Accessed 1 Aug 2011.

Vavreck, L., & Rivers, D. (2008). The 2006 cooperative congressional election study. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 18, 355–366.

Vecchione, M., & Caprara, G. V. (2009). Personality determinants of political participation: The contribution of traits and self-efficacy beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 487–492.

Westen, D., Blagov, P. S., Harenski, K., Kilts, C., & Hamann, S. (2006). Neural bases of motivated reasoning: An fMRI study of emotional constraints on partisan political judgment in the 2004 U.S. presidential election. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18, 1947–1958.

Wolk, C., & Nikolai, L. A. (1997). Personality types of accounting students and faculty: Comparisons and implications. Journal of Accounting Education, 15(1), 1–17.

Woods, S. A., & Hampson, S. E. (2005). Measuring the Big Five with single items using a bipolar response scale. European Journal of Personality, 19, 373–390.

Yang, J., McCrae, R. R., Jr. Costa, P. T., Dai, X., Yao, S., Taisheng, C., et al. (1999). Cross-cultural personality assessment in psychiatric populations: The NEO PI-R in the People’s Republic of China. Psychological Assessment, 11, 359–368.

Ziegert, A. L. (2000). The role of personality temperament and student learning in principles of economics: Further evidence. The Journal of Economic Education, 31, 307–322.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barry Burden, Casey Klofstad, Matthew Levendusky, Paul Goren, the anonymous reviewers, and the editors for comments on earlier versions. This research was funded by Yale’s Center for the Study of American Politics and Institution for Social and Policy Studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Question Wording and Coding

Partisanship

Stem Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a Democrat, a Republican, and Independent, or what?

-

If Democrat Would you call yourself a strong Democrat or a not very strong Democrat?

-

If Republican Would you call yourself a strong Republican or a not very strong Republican?

-

If Independent Do you think of yourself as closer to the Democratic or the Republican Party?

Direction

7-Point PID (−3 to 3): −3 = strong Rep.; −2 = weak Rep.; −1 = lean Rep.; 0 = Independent; 1 = lean Dem.; 2 = weak Dem.; 3 = strong Dem.

5-Point PID (−2 to 2): −2 = strong Rep.; −1 = weak/lean Rep.; 0 = Independent; 1 = weak/lean Dem.; 2 = strong Dem.

Strength

4-Point strength of party ID: 0 = “true” independents; 1 = leaning partisans; 2 = weak partisans; 3 = strong partisans

Affiliated with a major party (1 = yes) [strong or weak]: 0 = respondent said they were an Independent, other, or not sure (partisan “leaners” are coded as 0); 1 = respondent identified as a Republican or Democrat in the stem question

3-Point strength of party ID (0–2) [leaners/weak collapsed]: 0 = “true” independents; 1 = leaning/weak partisans; 2 = strong partisans

3-Point strength of party ID (0–2) [independents/leaners collapsed]: 0 = “true” independents/leaning partisans; 1 = weak partisans; 2 = strong partisans.

TIPI (10 Trait Pairs)

Here are a number of personality traits that may or may not apply to you. Please write a number next to each statement to indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with that statement. You should rate the extent to which the pair of traits applies to you, even if one characteristic applies more strongly than the other. I see myself as:

Extraversion Extraverted, enthusiastic; reserved, quiet (reverse coded)

Agreeableness Sympathetic, warm; critical, quarrelsome (reverse coded)

Conscientiousness Dependable, self-disciplined; disorganized, careless (reverse coded)

Emotional stability: Calm, emotionally stable; anxious, easily upset (reverse coded)

Openness Open to new experiences, complex; conventional, uncreative (reverse coded)

(1 = disagree strongly; 2 = disagree moderately; 3 = disagree a little; 4 = neither agree nor disagree; 5 = agree a little; 6 = agree moderately; 7 = agree strongly. Responses rescaled to range from 0 to 1).

Ideology

Thinking about politics these days, how would you describe the political viewpoint of the following individuals… Yourself?

5-Point ideology: (−2 = very conservative; −1 = conservative; 0 = moderate/“not sure”; 1 = liberal; 2 = very liberal)

3-Point strength of ideology: 0 = moderate; 1 = liberal/conservative; 2 = very liberal/conservative

When used as covariate: (very conservative; conservative; moderate/“not sure” [omitted, reference category]; liberal; very liberal).

Policy Opinions

Abortion Under what circumstances should abortion be legal? (Abortion should be illegal. It should never be allowed; Abortion should only be legal in special circumstances, such as when the life of the mother is in danger; Abortion should be legal, but with some restrictions (such as for minors or late-term abortions) [omitted, reference category]; Abortion should always be legal. There should be no restrictions on abortion.)

Civil unions Do you favor allowing civil unions for gay and lesbian couples? These would give them many of the same rights as married couples (strongly oppose; somewhat oppose; somewhat favor [omitted, reference category]; strongly favor).

Government health care Which comes closest to your view about providing health care in the United States? (Health insurance should be voluntary. Individuals should either buy insurance or obtain it through their employers as they do currently. The elderly and the very poor should be covered by Medicare and Medicaid as they are currently; Companies should be required to provide health insurance for their employees and the government should provide subsidies for those who are not working or retired [omitted, reference category]; The Government should provide everyone with health care and pay for it with tax dollars.)

Taxing the rich Do you favor raising federal taxes on families earning more than $200,000 per year? (strongly oppose; somewhat oppose; somewhat favor [omitted, reference category]; strongly favor).

Demographics

Female 0 = male; 1 = female

White 0 = non-White; 1 = White [omitted, reference category]

Black 0 = non-Black; 1 = Black

Hispanic 0 = non-Hispanic; 1 = Hispanic

Other race (native American, Asian, mixed, other) 0 = not other race; 1 = other race

Education 1 = no high school diploma; 2 = high school graduate; 3 = some college [omitted, reference category]; 4 = two year degree; 5 = college graduate; 6 = post-graduate

Family income 1 < $10,000; 2 = $10,000–14,999; 3 = $15,000–19,999; 4 = $20,000–24,999; 5 = $25,000–29,999 [omitted, reference category]; 6 = $30,000–39,999; 7 = $40,000–49,999; 8 = $50,000–59,999; 9 = $60,000–69,999; 10 = $70,000–79,999; 11 = $80,000–99,999; 12 = $100,000–119,999; 13 = $120,000–149,999; 14 = $150,000 or more; 15 = prefer not to say or missing

Age Years.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gerber, A.S., Huber, G.A., Doherty, D. et al. Personality and the Strength and Direction of Partisan Identification. Polit Behav 34, 653–688 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-011-9178-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-011-9178-5