Abstract

The RNA World is generally thought to have been an important link between purely prebiotic (>3.7 Ga) chemistry and modern DNA/protein biochemistry. One concern about the RNA World hypothesis is the geochemical stability of ribose, the sugar moiety of RNA. Prebiotic stabilization of ribose by solutions associated with borate minerals, notably colemanite, ulexite, and kernite, has been proposed as one resolution to this difficulty. However, a critical unresolved issue is whether borate minerals existed in sufficient quantities on the primitive Earth, especially in the period when prebiotic synthesis processes leading to RNA took place. Although the oldest reported colemanite and ulexite are 330 Ma, and the oldest reported kernite, 19 Ma, boron isotope data and geologic context are consistent with an evaporitic borate precursor to 2400-2100 Ma borate deposits in the Liaoning and Jilin Provinces, China, as well as to tourmaline-group minerals at 3300–3450 Ma in the Barberton belt, South Africa. The oldest boron minerals for which the age of crystallization could be determined are the metamorphic tourmaline species schorl and dravite in the Isua complex (metamorphism between ca. 3650 and ca. 3600 Ma). Whether borates such as colemanite, ulexite and kernite were present in the Hadean (>4000 Ma) at the critical juncture when prebiotic molecules such as ribose required stabilization depends on whether a granitic continental crust had yet differentiated, because in its absence we see no means for boron to be sufficiently concentrated for borates to be precipitated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An early phase of life’s origin, linking prebiotic chemistry with modern DNA/protein biochemistry, is generally thought to be the “RNA World,” wherein RNA served as an all-in-one molecule that both stored genetic information and catalyzed reactions needed for the self-replication required to sustain itself (e.g., Joyce 1989; Joyce and Orgel 2006; Orgel 1986; Robertson and Joyce 2010). Thus, the RNA World could have been an important phase in the transition from purely prebiotic chemistry towards modern biochemistry. This scenario assumes that the basic building blocks of RNA were readily available on the prebiotic Earth. Although there are plausible pathways for the prebiotic synthesis of components such as the nucleobases in RNA (Orgel 2004), problems exist with the synthesis and stability of ribose, the sugar moiety in RNA. In the prebiotic synthesis of sugars via the formose reaction (Boutlerow 1861), ribose is only a minor component of a complex mixture of sugars (Schwartz and de Graaf 1993; Shapiro 1988). Even though there may be synthesis and enrichment pathways that might result in a more preferential production and accumulation of ribose (Müller et al. 1990; Orgel 2004; Springsteen and Joyce 2004), the problem of the inherent instability of ribose at pH near 7 greatly compromises the possibility that significant quantities of ribose would have been present on the primordial Earth (Larralde et al. 1995).

In order to deal with the ribose instability issue it has been suggested that borate present in the primitive oceans acted as a complexing agent that stabilized ribose against decomposition (Benner 2004; Kim and Benner 2010; Prieur 2001; Ricardo et al. 2004; Scorei and Cimpoiaşu 2006). Benner and co-workers (Benner 2004; Ricardo et al. 2004) have reported experiments in which solutions containing ribose were incubated with the borate minerals colemanite, CaB3O4(OH)3(H2O), ulexite, NaCaB5O6(OH)6(H2O)5, and kernite, Na2B4O6(OH)2(H2O)3, which stabilized it, thereby leading Benner and co-workers to conclude that the presence of borate would allow prebiotic accumulation of ribose formed from simple organic precursors. The experiments performed by Prieur (2001) and Scorei and Cimpoiaşu (2006) involved solutions of boric acid and sodium tetraborate. The latter corresponds to either kernite, borax, or tincalconite, all of which have Na:B = 2:4, but differ in contents of hydroxyl and molecular water. Boron concentrations in the experiments cited above ranged from close to that of present day seawater to several orders of magnitude greater. Only Scorei and Cimpoiaşu (2006) quantitatively related exchange rate constants and half-life decomposition times with boron concentration in solution at different pH.

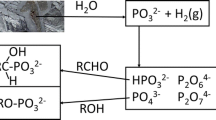

A role for borate in the origin of the RNA World presupposes that such borates were present at the Earth’s surface over 4 billion years ago so that high borate concentrations could be attained, at least locally, in marine or non-marine waters, but this supposition has not been examined in detail (Grew and Hazen 2010). None of these three minerals cited by Benner and co-workers has been found in rocks older than 330 Ma (Fig. 1); the oldest reported colemanite and ulexite are in the 330 Ma Maritimes basin, Canada (Grice et al. 2005; Roulston and Waugh 1981) and the oldest reported kernite is 19 Ma in the Kramer, California, and Kirka, Turkey, deposits (e.g., Helvaci and Ortí 2004; Smith and Medrano 2002). Sassolite (boric acid), H3BO3, has mostly been reported in Neogene or younger rocks (e.g., boric acid lagoons, fumaroles, efflorescences; Garrett 1998) or results from recent activity (e.g., Pring et al. 2000). The oldest boron minerals reported to date belong to the tourmaline supergroup of borosilicates, e.g., Na(Mg,Fe)3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)4, in metapelites and tourmalinites of the 3800-3700 Ma Isua complex, southwestern Greenland (Appel 1984, 1995; Chaussidon and Appel 1997; Meng 1988; Meng and Dymek 1987). Zircon and titanite U-Pb data give ages between ca. 3650 and ca. 3600 Ma for amphibolite-facies metamorphism in the Isua area (Crowley 2003; Nutman and Friend 2009), the age range presumed for tourmaline crystallization. Nonetheless, there is no reason to exclude a priori the existence of boron minerals or borate-rich waters 4 billion years ago, even though no trace of their presence is known in the geologic record. In this paper we review the history and evolution of boron minerals in order to evaluate the possibility that borates were present at the critical juncture in the early history of life.

Cumulative plot for 263 boron minerals based on reported occurrences and age determinations in the literature (Grew and Hazen 2010 and in preparation), showing boron mineral occurrences mentioned in the text

Boron and Its Minerals—Quintessentially Crustal

Of the 263 mineral species containing boron as an essential constituent, 241 are valid according to the International Mineralogical Association Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification (IMA CNMNC). The remaining 22 can be considered prospective, e.g., approved by the IMA CNMNC, but not yet published and unnamed, potentially valid species such as those listed by Smith and Nickel (2007). Boron minerals include one nitride, four fluorides, and 258 oxygen compounds (borates), of which 129 contain only B(O,OH)3 triangles and/or B(O,OH)4 tetrahedra such as colemanite, ulexite, and kernite, and 129 contain additional oxyanionic complexes of Be, C, Si, P, S, or As, such as the borosilicate tourmaline (e.g., Hawthorne et al. 2002).

Boron is a quintessential crustal element: it is enriched in the upper continental crust compared to other reservoirs, i.e., averages of 17 ppm vs. 2 ppm in the lower crust (Rudnick and Gao 2004), 0.26 ppm in primitive mantle (Palme and O’Neill 2004), and 0.775 ppm in CI chondrites (Lodders 2010). Moreover, B is very unevenly distributed in crustal rocks, and some reservoirs show marked enrichment relative to the average. For example, boron contents reach 40 ppm in granite, 180 ppm in oceanic sediment, and 270 ppm in altered oceanic crust (Leeman and Sisson 2002). Stilling et al. (2006) calculated an average B content of 213 ppm for a highly evolved granitic pegmatite (Tanco pegmatite, Manitoba, Canada). It is thus no surprise that boron minerals have been found only in the Earth’s crust, where they are largely restricted to such B-enriched rocks.

Boron minerals have not been reported in meteorites. There have been reports of boron minerals in rocks of mantle origin or from mantle depths, but involvement of crustal material in their formation cannot be excluded, e.g., kornerupine, (□,Mg,Fe)(Al,Mg,Fe)9(Si,Al,B)5O21(OH,F), where □ is a cation vacancy, as a secondary phase in a pyrope-spinel xenolith from Moses Rock dike, Utah (Padovani and Tracy 1981), where the fluids causing the alteration could have originated in the crust (Smith 1995). Tourmaline has been reported in kimberlites and lamproites, e.g., Riley County, Kansas, (Brookins 1969) and at several localities in Canada, U.S. and Australia (Fipke et al. 1995). Although Fipke et al. (1995) suggested the tourmaline might have originated from boron associated with kimberlite and lamproite, Roger Mitchell (personal communication 2010) wrote me that all tourmaline in kimberlite and lamproite is xenocrystal—never a primary phase; he made no mention of any boron mineral in his book on kimberlites and related rocks (Mitchell 1995). Cubic boron nitride (BN) has been reported to form at mantle depths, but it was found in a small rock fragment interpreted to be subducted continental crust (Dobrzhinetskaya et al. 2009).

Geologic Occurrence and History of Borate Minerals

Boron minerals are found in a large number of environments where B has been concentrated by some process, either magmatic or involving an aqueous fluid, but by far the greatest diversity (80 species) is found in evaporites, occurring in both non-marine (e.g., Helvaci and Ortí 2004; Smith and Medrano 2002) and marine (e.g., Braitsch 1971; Garrett 1998; Grice et al. 2005) environments, and at scales ranging from layers a few meters thick to vast lacustrine deposits of economic importance such as Searles Lake and Boron (Kramer), California. Continental deposits are most extensively developed in down-faulted basins associated with active collisional zones (e.g., California, Chile, Argentina, Turkey, China). However, the tectonic associations of marine deposits are more varied, i.e., the Mississippian deposits of Maritime Canada are in fault-bounded extensional basins (Pascucci and Gibling 2003).

Volcanic activity, including thermal springs and hydrothermal fluids, are an important source of B to continental evaporites, but volcanism plays a less important role, or none at all, as a source of B for marine deposits. Whether the diversity of mineral species characteristic of continental deposits is an original feature of the evaporite or the result of deep burial and post-burial diagenesis and is a matter of dispute, and could vary among deposits. More specifically, borax and ulexite precipitate directly from saline solutions, whereas kernite forms at moderately elevated temperatures (37°–59°C) during diagenesis, depending on solution salinity (Bowser 1965). Helvaci and Ortí (2004) proposed that colemanite precipitated from solution at the Kirka borate deposit, western Turkey, whereas Smith and Medrano (2002) argued that it is a diagenetic phase in the California deposits, although Bowser (1965) admitted some colemanite might be primary in the Kramer deposit. In addition, Tanner (2002) suggests that some colemanite in the Furnace Creek Formation, California may have formed as a primary precipitate. In summary, most California occurrences appear to have resulted from the diagenesis of precursor minerals. Ulexite and colemanite, but not kernite, have been reported from marine evaporites.

Very few instances are known of boron-bearing evaporites being preserved from the Precambrian. Examples give the impression that extensive precipitation began only in the lower Cambrian, as in the case of the Angara suite (Fig. 1) in the Korshunovskoye and Nepskoye deposits on the Siberian Platform, Irkutsk Oblast’, Russia (Mazurov et al. 2007; Semeykina and Kozlova 1985). The only borate reported from a Precambrian evaporite is chambersite (Mn3B7O13Cl) associated with algal dolostone in the 1500 Ma Gaoyuzhuang Formation, China (Fan et al. 1999; Shi et al. 2008). Fan et al. (1999) concluded that the deposit formed in a subtidal lagoon of an epicontinental sea, and that chambersite precipitated directly under conditions of high salinity, high B, Mn, and Mg concentrations, and weak alkalinity; submarine volcanic eruptions are believed to be the main source of B.

The oldest reported occurrence of a borate mineral readily soluble in water is teepleite, Na2B(OH)4Cl, but only as a few daughter crystals within fluid inclusions in topaz from the Volynian pegmatites, Ukraine (Kalyuzhnyy 1958) for which the age is 1770 Ma (Fig. 1, Pavlishin and Dovgyi 2007). The occurrence of teepleite as an evaporitic mineral is limited to Holocene lake deposits in California (e.g., Gale et al. 1939). Thus, if sufficiently protected, even borates readily soluble in water such as teepleite can survive at least 1770 m.y.

Nonetheless, circumstantial evidence, notably microstructures and B isotopes, suggests that B-bearing evaporites were deposited in the Precambrian, but were subsequently replaced by borates and borosilicates of metamorphic or hydrothermal origin, e.g., tourmaline-bearing marine and non-marine evaporites in rifts within the 1000-800 Ma Duruchaus Formation in the Damara Orogen, Namibia (e.g., Behr et al. 1983; Henry et al. 2008) and tourmalinite inferred to have a non-marine evaporite source of B in the ~1700 Ma Willyama Supergroup, Broken Hill, Australia (e.g., Slack et al. 1989, 1993). Perhaps the most spectacular example comprises deposits of metamorphic borates in the Liaoning and Jilin Provinces, China (Fig. 1). Peng and Palmer (2002) reported geological, geochemical, and boron isotope data supporting a scenario in which non-marine evaporite precursors deposited in playa lakes 2400-2100 Ma ago recrystallized under greenschist- to amphibolite-facies conditions at 2100-2000 Ma to form borate assemblages dominated by szaibélyite, MgBO2(OH), suanite, Mg2B2O5, and ludwigite, (Mg, Fe2+)2Fe3+BO5. The two anhydrous borates are characteristic of relatively high-temperature contact metamorphic deposits, such as skarns (e.g., Anovitz and Grew 2002). The Liaoning-Jilin area first experienced subduction of oceanic crust below an Archean craton, then continental collision and lastly development of extensional basins analogous to the Cenozoic basins that contain evaporitic borates in Turkey and Argentina (Peng and Palmer 2002).

An even more ancient evaporitic precursor has been suggested for tourmaline-bearing greenschist-facies metasedimentary rocks in the Upper Onverwacht Group (3300–3450 Ma) of the Barberton greenstone belt in South Africa (Fig. 1; Byerly and Palmer 1991; Byerly et al. 1996). Byerly and Palmer (1991) cited siliceous pseudomorphs, most likely after nahcolite, NaHCO3 (Lowe and Fisher Worrell 1999), and B isotopes as evidence for a marine evaporite precursor to tourmalinized rocks, and proposed a two-stage B enrichment whereby evaporitic B was mobilized by hydrothermal solutions to mineralize algal stromatolites either subaerially or in shallow marine waters.

There is no evidence for an evaporitic precursor to the two metamorphic tourmaline species dravite and schorl in the Isua complex, Greenland, which at ca. 3650—ca. 3600 Ma (metamorphic age) contains the oldest B minerals reported to date (Fig. 1). Meng (1988) and Meng and Dymek (1987) described tourmaline cores inferred to be of detrital origin with compositions plotting in the fields of both metasedimentary and igneous tourmaline (Henry and Guidotti 1985), suggesting the intriguing possibility of tourmaline-bearing continental crust older than that in the Isua belt and supplying detritus to it. However, to date no tourmaline or other boron mineral has been reported from exposures of the oldest reported exposed continental crust (4000–4280 Ma), which is composed of orthogneisses intermediate and mafic in composition (Bowring and Williams 1999; O’Neil et al. 2008). Although tourmaline does occur in the same metamorphosed quartz-pebble conglomerates from the Jack Hills belt, Western Australia as the zircons older than 4000 Ma (Maas et al. 1992; Cavosie et al. 2004; Rasmussen et al. 2010), there is no evidence that the tourmaline is as old as these zircons, e.g., tourmaline has not yet been found as inclusions in them (Maas et al. 1992; Harrison 2009). Estimating the age of the tourmaline depends on whether it is metamorphic or detrital, but this is ambiguous in many cases (Cavosie et al. 2004). If the tourmaline were metamorphic, its age would more likely be 2650 Ma, the age inferred for the main event (Rasmussen et al. 2010). An older age is likely if the tourmaline were detrital. According to Rasmussen et al (2010) the metaconglomerate was deposited between 3050 and 2650 Ma, which would provide a minimum age for detrital tourmaline. Nonetheless, it still probably would be no older than 3600 Ma, because most zircons are between ca. 3600 and 3000 Ma in age (Maas et al. 1992; Rasmussen et al. 2010).

Were there Borates or Boron-rich Waters Before 4000 Ma?

Although we have no firm evidence that any boron mineral was present prior to 3700 Ma, we cannot a priori exclude such a possibility if a granitic continental crust had already differentiated by 4000 Ma, or if oceans were present with an average B concentration not significantly less than the present value of 4.5 ppm B (Nozaki 1997). Either situation could lead to localized B enrichments for the formation of borates or borate-rich waters. Hawkesworth et al. (2010) concluded that there is evidence in zircons from Jack Hills, Western Australia, for a felsic component to a crust dominantly mafic in composition 4300 Ma ago, but failure of this Hadean crust to survive conditions on a hotter Earth is no surprise. In a comprehensive review of data from these zircons, including Hf isotopes, Harrison (2009) concluded that the Earth at 4300 Ma “was behaving much as it does today,” in which subduction, albeit shallow, played a major role and water condensed in a global ocean. If indeed this had been the case, it is plausible that the global boron cycle might have resembled the current cycle (Park and Schlesinger 2002; Carrano et al. 2009) minus the anthropogenic components and emissions from land vegetation. An important flux today is weathering of exposed rock. Ushikubo et al. (2008) cited high Li contents and fractionated δ7Li values of the Hadean zircons as evidence for the presence of chemically differentiated and weathered crust by 4300 Ma. If continental crust were as enriched in Li at 4300 Ma as it has been since the Archean, then it is reasonable to assume that B was also enriched to a comparable degree, and B flux from land to sea could have approached today’s levels. Harrison (2009) questioned the significance of the Li data reported by Ushikubo et al. (2008), because of the very real possibility that Li diffuses too readily to preserve the Hadean signature. However. Cherniak and Watson (2010) reported experimental Li diffusivities in zircon that are consistent with little mobilization of Li in zircon under the amphibolite-facies conditions reported for the metaconglomerate (andalusite present), and thus the measured Li contents are likely to be original. Cherniak and Watson (2010) did not discuss the possibility that the isotopic signature might be disrupted even when bulk Li content has not been, so it is less certain whether the Li isotopic signatures in zircon would survive an amphibolite-facies event.

If we accept the Harrison (2009) scenario, together with the zircon Li data, at face value, then it seems reasonable to suggest a scene on land at 4300 Ma not unlike present-day landscapes lacking vegetation. Borate deposits precipitated from thermal waters in the Hadean need not be restricted to analogues of the Cenozoic and Holocene continental evaporites deposited in tectonically active areas. One might imagine small pools of brine sourced by B-enriched thermal waters and concentrated by evaporation into the atmosphere. A comparable scenario, but one where concentration was achieved by freezing, has been proposed to explain borax inferred to be pseudomorphic after kernite in boulders with nahcolite in supraglacial moraine near the Colbert Hills, Transantarctic Mountains (Fitzpatrick and Muhs 1989; Fitzpatrick et al. 1990; Faure and Mensing 2010), which are no longer tectonically active.

Even if there were no borates on land, there could have been sufficient concentration of B for stabilizing ribose in the ocean had plate tectonics been active. As far as we are aware, no one has attempted to estimate B concentrations in the early oceans. Izawa et al. (2010) suggested a three-stage evolution for the oceans overall: (1) a “pre-uniformitarian” period from ca. 4200 Ma to ca. 3700 Ma when under heavy bombardment the dominant source for solutes was meteorites and seawater was more saline than now and dominated by MgSO4 rather than NaCl; (2) a transitional period of intermediate seawater composition from ca. 3700 Ma to ca. 3300-3000 Ma when the dominant source was weathered crust; and (3) after ca. 3300-3000 Ma when influx of crustal material had wiped out the meteoritic signature to give a seawater composition close to that today. Nonetheless, even during the first stage, had there been exposed granitic crust being weathered or hydrothermal fluids leaching boron from oceanic crust, boron could have entered the oceans if river flow and circulation around hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor were as important fluxes between the ocean and crust as they are today. Leeman and Sisson (2002) noted that B is commonly enriched in oceanic crust (to 270 ppm B) exposed in fracture zones because B in seawater is adsorbed onto clays and other hydrous secondary phases, a plausible process in a Hadean ocean containing several ppm B.

Nonetheless, the presence of continental crust so early in Earth’s history remains a hotly debated topic. Citing new Hf isotope measurements, also on zircons from Jack Hills, Kemp et al. (2010) come to the opposite conclusion of Harrison (2009), viz., the new Hf data “do not require a plate tectonic regime for the Hadean Earth similar to that operating today.” Instead, Kemp et al. (2010) contend that the data are consistent with magma generation by melting of enriched basalt in a thickened volcanic pile; there is no need to invoke a metasedimentary source for the Jack Hills zircons. Their model envisages a “nascent hydrosphere/steam atmosphere.” In this setting, concentrations of B either on land or in the sea sufficient to play a role in ribose stabilization are thus unlikely. Alternative stabilizers, such as aqueous silicate (Lambert et al. 2010a, b), could be more plausible. In addition, crystallization of products formed from the reaction of ribose with prebiotic reagents such as cyanamide could have played a role in sequestering and preservation of ribose for eventual incorporation into early RNA (Springsteen and Joyce 2004).

References

Anovitz LM, Grew ES (2002) Mineralogy, petrology and geochemistry of boron: an introduction. In: Grew ES, Anovitz LM (eds), Boron: mineralogy, petrology and geochemistry. Rev Mineral 33, 2nd printing. Mineralogical Society of America, Washington, pp 1–40, 115–116, 385

Appel PWU (1984) Tourmaline in the Early Archaean Isua supracrustal belt, West Greenland. J Geol 92:599–605

Appel PWU (1995) Tourmalinites in the 3800 Ma old Isua supracrustal belt, West Greenland. Precambrian Res 72:227–234

Behr H-J, Ahrendt H, Porada H, Röhrs J, Weber K (1983) Upper Proterozoic playa-lake deposits in the Damara orogen, SWA/Namibia. Spec Publ Geol Soc S Afr 11:1–20

Benner SA (2004) Understanding nucleic acids using synthetic chemistry. Acc Chem Res 37:784–797

Boutlerow A (1861) Formation synthétique d’une substance sucrée. C R Acad Sci 53:145–147

Bowring SA, Williams IS (1999) Priscoan (4.00–4.03 Ga) orthogneisses from northwestern Canada. Contrib Mineral Petrol 134:3–16

Bowser CJ (1965) Geochemistry and petrology of the sodium borates in the non-marine evaporite environment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Los Angeles

Braitsch O (1971) Salt deposits. Their origin and composition. Springer, Berlin

Brookins DG (1969) A list of minerals found in Riley County kimberlites. Trans Kans Acad Sci 72(3):365–373

Byerly GR, Palmer MR (1991) Tourmaline mineralization in the Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa: early Archean metasomatism by evaporite-derived boron. Contrib Mineral Petrol 107:387–402

Byerly GR, Kröner A, Lowe DR, Todt W, Walsh MM (1996) Prolonged magmatism and time constraints for sediment deposition in the Early Archean Barberton greenstone belt: evidence from the Upper Onverwacht and Fig Tree groups. Precambrian Res 78:125–138

Carrano CJ, Schellenberg S, Amin SA, Green DH, Küpper FC (2009) Boron and marine life: a new look at an enigmatic bioelement. Mar Biotechnol 11:431–440

Cavosie AJ, Wilde SA, Liu D, Weiblen PW, Valley JW (2004) Internal zoning and U–Th–Pb chemistry of Jack Hills detrital zircons: a mineral record of early Archean to Mesoproterozoic (4348–1576 Ma) magmatism. Precambrian Res 135:251–279

Chaussidon M, Appel PWU (1997) Boron isotopic composition of tourmalines from the 3.8-Ga-old Isua supracrustals, West Greenland: implications on the δ11B value of early Archean seawater. Chem Geol 136:171–180

Cherniak DJ, Watson EB (2010) Li diffusion in zircon. Contrib Mineral Petrol 160:383–390

Crowley JL (2003) U–Pb geochronology of 3810–3630 Ma granitoid rocks south of the Isua greenstone belt, southern West Greenland. Precambrian Res 126:235–257

Dobrzhinetskaya LF, Wirth R, Yang J, Hutcheon ID, Weber PK, Green HW II (2009) High-pressure highly reduced nitrides and oxides from chromitite of a Tibetan ophiolite. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106:19233–19238

Fan D, Yang P, Wang R (1999) Characteristics and origin of the Middle Proterozoic Dongshuichang chambersite deposit, Jixian, Tianjin, China. Ore Geol Rev 15:15–29

Faure G, Mensing TM (2010) The Transantarctic mountains. Rocks, ice, meteorites and water. Springer, Dordrecht

Fipke CE, Gurney JJ, Moore RO (1995) Diamond exploration techniques emphasising indicator mineral geochemistry and Canadian examples. Geol Surv Can Bull 423:1–86

Fitzpatrick JJ, Muhs DR (1989) Borax in the supraglacial moraine of the Lewis Cliff, Buckley Island Quadrangle—First Antarctic occurrence. Antarct J US 24(5):63–65

Fitzpatrick JJ, Muhs DR, Jull AJT (1990) Saline minerals in the Lewis Cliff ice tongue, Buckley Island Quadrangle, Antarctica. Antarct Res Ser 50:57–69

Gale WA, Foshag WF, Vonsen M (1939) Teepleite, a new mineral from Borax Lake, California. Am Mineral 24:48–52

Garrett DE (1998) Borates. Handbook of deposits, processing, properties, and use. Academic, San Diego

Grew E, Hazen RM (2010) Evolution of boron minerals: has early species diversity been lost from the geological record? Geol Soc Am Abstr Programs 42(5):92

Grice JD, Gault RA, Van Velthuizen J (2005) Borate minerals of the Penobsquis and Millstream deposits, southern New Brunswick, Canada. Can Mineral 43:1469–1487

Harrison TM (2009) The Hadean crust: evidence from >4 Ga zircons. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 37:479–505

Hawkesworth CJ, Dhuime B, Pietranik AB, Cawood PA, Kemp AIS, Storey CD (2010) The generation and evolution of the continental crust. J Geol Soc 167:229–248

Hawthorne FC, Burns PC, Grice JD (2002) The crystal chemistry of boron. In: Grew ES, Anovitz LM (eds) Boron: mineralogy, petrology and geochemistry. Rev Mineral 33, 2nd printing. Mineralogical Society of America, Washington, D.C., pp 41–116, 385.

Helvaci C, Ortí F (2004) Zoning in the Kirka borate deposit, western Turkey: primary evaporitic fractionation or diagenetic modifications? Can Mineral 42:1179–1204

Henry DJ, Guidotti CV (1985) Tourmaline as a petrogenetic indicator mineral: an example from the staurolite-grade metapelites of NW Maine. Am Mineral 70:1–15

Henry DJ, Sun H, Slack JF, Dutrow BL (2008) Tourmaline in meta-evaporites and highly magnesian rocks: perspectives from Namibian tourmalinites. Eur J Mineral 20:889–904

Izawa MRM, Nesbitt HW, MacRae ND, Hoffman EL (2010) Composition and evolution of the early oceans: evidence from the Tagish Lake meteorite. Earth Planet Sci Lett 298:443–449

Joyce GF (1989) RNA evolution and the origin of life. Nature 338:217–224

Joyce GF, Orgel LE (2006) Progress toward understanding the origin of the the RNA world. In: Gesteland RF, Cech TR, Atkins JF (eds) The RNA world, 3rd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, pp 23–56

Kalyuzhnyy VA (1958) On the studies of “prisoner” minerals in multiphase inclusions. Mineral Sb L’vovsk Geol Obshchestva 12:116–128 (in Russian)

Kemp AJS, Wilde SA, Hawkesworth CJ, Coath CD, Nemchin A, Pidgeon RT, Vervoort JD, DuFrane SA (2010) Hadean crustal evolution revisited: new constraints from Pb–Hf isotope systematics of the Jack Hills zircons. Earth Planet Sci Lett 296:45–56

Kim H-J, Benner SA (2010) Comment on “The silicate-mediated formose reaction: Bottom-up synthesis of sugar silicates”. Science 329:902-a

Lambert JB, Gurusamy-Thangavelu SA, Ma K (2010a) The silicate-mediated formose reaction: bottom-up synthesis of sugar silicates. Science 237:984–986

Lambert JB, Gurusamy-Thangavelu SA, Ma K (2010b) Response to comment on “The silicate-mediated formose reaction: Bottom-up synthesis of sugar silicates”. Science 329:902-b

Larralde R, Robertson MP, Miller SL (1995) Rates of decomposition of ribose and other sugars: implications for chemical evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci 92:8158–8160

Leeman WP, Sisson VB (2002) Geochemistry of boron and its implications for crustal and mantle processes. In: Grew ES, Anovitz LM (eds) Boron: mineralogy, petrology and geochemistry. Rev Mineral 33, 2nd printing. Mineralogical Society of America, Washington, D.C., pp 645–708

Lodders K (2010) Solar system abundances of the elements. In: Goswami A, Reddy BE (eds) Principles and perspectives in cosmochemistry. Astrophysics and space science proceedings. Springer, New York, pp 379–417

Lowe DR, Fisher Worrell G (1999) Sedimentology, mineralogy, and implications of silicified evaporites in the Kromberg Formation, Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa. In: Lowe DR, Byerly GR (eds) Geologic evolution of the Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa. Geol Soc Am Spec Pap 329:167–188

Maas R, Kinny PD, Williams IS, Froude DO, Compston W (1992) The Earth’s oldest known crust: a geochronological and geochemical study of 3900–4200 Ma old detrital zircons from Mt. Narryer and Jack Hills, Western Australia. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 56:1281–1300

Mazurov MP, Grishina SN, VYe I, Titov AT (2007) Metasomatism and ore formation at contacts of dolerite with saliferous rocks in the sedimentary cover of the southern Siberian Platform. Geol Rudn Mestorozd 49(4):306–320 (in Russian)

Meng Y (1988) Tourmaline from the Isua supracrustal belt, southern West Greenland. Master’s Thesis, Washington University, Saint Louis, Missouri

Meng Y, Dymek RF (1987) Compositional relationships and petrogenetic implications of tourmaline from the 3.8 Ga Isua supracrustal belt, West Greenland. Geol Soc Am Abstr Programs 19(7):770

Mitchell RH (1995) Kimberlites, orangeites, and related rocks. Plenum, New York

Müller D, Pitsch S, Kittaka A, Wagner E, Wintner CE, Eschenmoser A (1990) Chemistry of alpha-aminonitriles. Aldomerisation of glycolaldehyde phosphate to rac-hexose 2, 4, 6-triphosphates and in presence of formaldehyde) rac-pentose 2, 4-diphosphates: rac-allose 2, 4, 6-triphosphate and rac-ribose 2, 4-diphosphate are the main reaction products. Helv Chim Acta 73:1410–1468 (in German)

Nozaki Y (1997) A fresh look at element distribution in the North Pacific. Eos Trans Am Geophys Union 78:221 and http://www.agu.org/pubs/eos-news/supplements/1995-2003/97025e.shtml. Accessed 12 December 2010

Nutman AP, Friend CRL (2009) New 1:20, 000 scale geological maps, synthesis and history of investigation of the Isua supracrustal belt and adjacent orthogneisses, southern West Greenland: a glimpse of Eoarchaean crust formation and orogeny. Precambrian Res 172:189–211

O’Neil J, Carlson RW, Francis D, Stevenson RK (2008) Neodymium-142 evidence for Hadean crust. Science 321:1828–1831

Orgel LE (1986) RNA catalysis and the origin of life. J Theor Biol 123:127–149

Orgel LE (2004) Prebiotic chemistry and the origin of the RNA World. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 39:99–123

Padovani ER, Tracy RJ (1981) A pyrope-spinel (alkremite) xenolith from Moses Rock Dike: first known North American occurrence. Am Mineral 66:741–745

Palme H, O’Neill St C (2004) Cosmochemical estimates of mantle composition. In: Carlson RW (ed) The mantle and core, vol. 2 of Holland HD, Turekian KK (eds) Treatise on Geochemistry. Elsevier-Pergamon, Oxford, pp 1–38

Park H, Schlesinger WH (2002) Global biogeochemical cycle of boron. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 16(4):1072. doi:10.1029/2001GB001766,2002

Pascucci V, Gibling MR (2003) Late Palaeozoic evolution of the eastern Maritimes Basin, Atlantic Canada. Boll Soc Geol Ital 2:219–237

Pavlishin VI, Dovgyi SA (2007) Mineralogy of the Volynian chamber pegmatites, Ukraine. Mineral Alm 12:6–125

Peng Q-M, Palmer MR (2002) The Paleoproterozoic Mg and Mg-Fe borate deposits of Liaoning and Jilin Provinces, northeast China. Econ Geol 97:93–108

Prieur BE (2001) Étude de l’activité prébiotique potentielle de l’acide borique. C R Acad Sci Chim/Chem 4:667–670

Pring A, Kolitsch U, Francis G (2000) Additions to the mineralogy of the Iron Monarch deposit, Middleback Ranges, South Australia. Aust J Mineral 6(1):9–23

Rasmussen B, Fletcher IR, Muhling JR, Wilde SA (2010) In situ U–Th–Pb geochronology of monazite and xenotime from the Jack Hills belt: Implications for the age of deposition and metamorphism of Hadean zircons. Precambrian Res 180:26–46

Ricardo A, Carrigan MA, Olcott AN, Benner SA (2004) Borate minerals stabilize ribose. Science 303:196

Robertson MP, Joyce GF (2010) The Origins of the RNA World. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003608

Roulston BV, Waugh DCE (1981) A borate mineral assemblage from the Penobsquis and Salt Springs evaporite deposits of southern New Brunswick. Can Mineral 19:291–301

Rudnick RL, Gao S (2004) Composition of the continental crust. In: Rudnick RL (ed) The crust, vol. 3 of Holland HD, Turekian KK (eds) Treatise on Geochemistry. Elsevier-Pergamon, Oxford, pp 1–64

Schwartz AW, de Graaf RM (1993) The prebiotic synthesis of carbohydrates: a reassessment. J Mol Evol 36:101–106

Scorei R, Cimpoiaşu VM (2006) Boron enhances the thermostability of carbohydrates. Orig Life Evol Biosph 36:1–11

Semeykina LK, Kozlova VN. (1985) Mineralogical-petrographic characteristics of the potash rocks of the Nepskoye basin. In: Obshchiye Problemy Galogenezesa, Nauka, Moscow, pp 143–148 (in Russian)

Shapiro R (1988) Prebiotic ribose synthesis: a critical analysis. Orig Life Evol Biosph 18:71–85

Shi X, Zhang C, Jiang G, Liu J, Wang Y, Liu D (2008) Microbial mats in the Mesoproterozoic carbonates of the North China platform and their potential for hydrocarbon generation. J China Univ Geosci 19:549–566

Slack JF, Palmer MR, Stevens BPJ (1989) Boron isotope evidence for the involvement of non-marine evaporites in the origin of the Broken Hill ore deposits. Nature 342:913–916

Slack JF, Palmer MR, Stevens BPJ, Barnes RG (1993) Origin and significance of tourmaline-rich rocks in the Broken Hill district, Australia. Econ Geol 88:505–541

Smith D (1995) Chlorite-rich ultramafic reaction zones in Colorado Plateau xenoliths: recorders of sub-Moho hydration. Contrib Mineral Petrol 121(185):200

Smith DGW, Nickel EH (2007) A system of codification for unnamed minerals: report of the subcommittee for unnamed minerals of the IMA commission on new minerals, nomenclature and classification. Can Mineral 45:983–1055

Smith GI, Medrano MD (2002) Continental borate deposits of Cenozoic age. In: Grew ES, Anovitz LM (eds) Boron: mineralogy, petrology and geochemistry. Rev Mineral 33, 2nd printing. Mineralogical Society of America, Washington, D.C., pp 263–298

Springsteen G, Joyce GF (2004) Selective derivatization and sequestration of ribose from a prebiotic mix. J Am Chem Soc 126:9578–9583

Stilling A, Černý P, Vanstone PJ (2006) The Tanco pegmatite at Bernic Lake, Manitoba. XVI Zonal and bulk compositions and their petrogenetic significance. Can Mineral 44:599–623

Tanner LH (2002) Borate formation in a perennial lacustrine setting: Miocene–Pliocene Furnace Creek Formation, Death Valley, California, USA. Sediment Geol 148:259–273

Ushikubo T, Kita NT, Cavosie AJ, Wilde SA, Rudnick RL, Valley JW (2008) Lithium in Jack Hills zircons: Evidence for extensive weathering of Earth’s earliest crust. Earth Planet Sci Lett 272:666–676

Acknowledgements

We thank Nikolay N. Pertsev for assistance in obtaining copies of critical literature that would otherwise be inaccessible and two anonymous reviewers for thoughtful and constructive comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. Additionally, Antonio Lazcano and H. James Cleaves provided helpful comments. ESG is supported by U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) grant EAR 0837980 to the University of Maine. JLB is also affiliated with the Center for Chemical Evolution at the Georgia Institute of Technology, which is jointly supported by NSF (CHE-1004570) and NASA’s Astrobiology Institute. RMH thanks NSF (EAR-1023889), Astrobiology Institute of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Deep Carbon Observatory, and the Carnegie Institution for Science for support of research on mineral evolution and the origin of life.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grew, E.S., Bada, J.L. & Hazen, R.M. Borate Minerals and Origin of the RNA World. Orig Life Evol Biosph 41, 307–316 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11084-010-9233-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11084-010-9233-y