Abstract

This article investigates a palatalization process called Surface Velar Palatalization that turns /k g/ into [kj gj] before the front vowel e. What would appear to be a trivial rule, k g → kjgj/—ε, turns out to be a highly complex process. The complexity is caused by several independent factors. First, Surface Velar Palatalization, k g → kjgj, competes with Phonemic Velar Palatalization, k g → ʧ ʤ. Second, some but not all changes are restricted to derived environments. Third, some suffixes appear to be exceptions to one type of Palatalization but not to the other type. Fourth, /x/ behaves in an ambivalent way by undergoing one but not the other type of Palatalization. Fifth, Palatalization constraints interacting with segment inventory constraints yield different results in virtually the same contexts.

I argue that the complexity of Surface Velar Palatalization motivates derivational levels in Optimality Theory. Further, the condition of derived environments is expressed as a constraint that is ranked differently at different levels of evaluation.

A historical analysis of Surface Velar Palatalization tells the story of how the process came into being and operated for centuries in an unrestricted way. It subsequently became restricted to derived environments, which led to pronunciation reversals of the historical Duke of York type: gε → gjε → gε.*

Similar content being viewed by others

This article investigates a palatalization process in Polish called Surface Velar Palatalization,Footnote 1 which turns /k g/ into [kj gj] before the front vowel e. Aside from some cursory remarks in Gussmann (1980) and Rubach (1984), Surface Velar Palatalization has not been discussed in the generative literature to date, so the material is new.Footnote 2 What would appear to be a trivial rule, k g → kjgj/—ε, turns out to be a highly complex but fully regular process. Accounting for Surface Velar Palatalization is therefore a challenge and a test of adequacy for phonological theory.

On the theoretical side, this paper is a contribution to Stratal Optimality Theory (Stratal OT, henceforth) in two ways. First, it provides a new argument for the distinction of levels or strata stemming from the hitherto unexplored role played by segment inventories. Second, it investigates derived environments in Palatalization and postulates that they are best captured as an OT constraint that can be ranked differently at different levels of derivation. Third, a historical study of Surface Velar Palatalization contributes to an understanding of the life cycle of a process that Stratal OT is designed to model.

Arguments for Stratal OT have typically been based on opacity (Kiparsky 2000; Bermúdez-Otero 1999; Rubach 2000a). The weak point of such arguments is that Standard Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky 2004; McCarthy and Prince 1995) has developed a number of auxiliary theories that can handle opacity, including Output-Output Theory (Benua 1997), Sympathy Theory (McCarthy 1999) and OT-Candidate Chains (McCarthy 2007). The opacity argument for strata is weak because it reduces to the demonstration that Stratal OT can account for opacity by invoking one mechanism (strata/levels) while Standard OT uses several unrelated mechanisms, so is not homogeneous. The point of this paper is that strata/levels are motivated by different inventories, so the type of admissible segments at the stem level is different from the type of admissible segments at the word level and that, in turn, is different from the type of admissible segments at the postlexical level. Inventory arguments are important because they are not amenable to restatement in terms of OT auxiliary theories. Selecting Surface Velar Palatalization for making the inventory argument is a good choice because the process unveils massive differences in inventories at level 1, level 2 and level 3.

The second point of this paper—derived environments—brings up two issues: first, the issue of how derived environments (DE, henceforth) should be expressed formally and, second, the issue of the life cycle of a historical process. It is argued that the role of derived environments is best defined as a constraint that, like any OT constraint, can be ranked differently at different levels in Stratal OT. A historical analysis of Surface Velar Palatalization tells the story of how the process came into being and operated for centuries in an unrestricted way. It subsequently became restricted to derived environments, which led to pronunciation reversals of the historical Duke-of-York type: gε → gjε → gε.

This article is organized as follows. Section 1 introduces the relevant background facts of Polish phonology (Sect. 1.1) and the assumptions of Stratal OT (Sect. 1.2). Section 2 discusses Phonemic Velar Palatalization while Sect. 3 provides an OT analysis of Surface Velar Palatalization and related processes, making the point about segment inventory constraints and derived environments. Section 4 looks at a historical development of Surface Velar Palatalization from Old Polish, through Middle Polish, to Modern Polish. Section 5 summarizes the rankings of the constraints and their interaction. Section 6 concludes with a summary of the results. The Appendix extends the analysis to coronal and labial inputs and to i as the trigger of Palatalization.

1 Background

This section prepares the ground for an analysis of Velar Palatalization. I begin with the presentation of descriptive facts of Polish phonology in the fragment that is relevant for this article. Subsequently, I introduce the assumptions of Stratal OT and the constraint apparatus for an analysis of Palatalization.

1.1 Descriptive background

Polish has a rich system of consonants. One reason for this richness is that the distinction ‘hard’ versus ‘soft’ consonants cuts without exception across the whole system. According to Wierzchowska (1963:9–11 and 1971:149), hard consonants are pronounced with a tongue body configuration for the back vowel [a] while soft consonants have a tongue body position characteristic for front vowels. Consequently, in terms of features, hard consonants are characterized as [+back] while soft consonants are [-back]. In (1), I look at a fragment of the phonetic inventory that includes coronals and dorsals. For compactness, I list only voiceless obstruents, noting that [x] has a voiced counterpart only as a result of Voice Assimilation. I assume the Halle–Sagey model of Feature Geometry (Halle 1992; Sagey 1986), in which the features [±anterior] and [±strident] are dependents of the CORONAL node, so they are not applicable to dorsals.

-

(1)

Surface coronal and dorsal obstruents in Polish

C O R O N

D O R S

t

tj

s

sj

ʦ

ʦj

ʃ

ʃj

ʧ

ʧj

ɕ

tɕ

k

kj

x

xj

back

+

–

+

–

+

–

+

–

+

–

–

–

+

–

+

–

contin

–

–

+

+

–

–

+

+

–

–

+

–

–

–

+

+

anter

+

+

+

+

+

+

–

–

–

–

–

–

strid

–

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

All of these consonants occur in the surface representation, as the following examples show.

-

(2)

Hard versus soft consonants in Polish

brat [t] ‘brother’ – brat Janka [tj j] ‘Janek’s brother’:

palatalized dental stop

zobacz [ʧ] ‘see’ – zobacz je [ʧj j] ‘see them’:

palatalized postalveolar affricate

głos [s] ‘voice’ – głosIreny [sj i] ‘Irena’s voice’:

palatalized alveolar fricative

dasz [ʃ] ‘give’ – daszje [ʃj j] ‘you will give them’:

palatalized postalveolar fricative

krok [k] ‘step’ – krokIreny [kj i] ‘Irena’s step’:

prevelar stop

duch [x] ‘spirit’ – duchIreny [xj i] ‘Irena’s spirit’:

prevelar fricative

ciało [ tɕa] ‘body’:

prepalatal affricate

siano [ɕa] ‘hay’:

prepalatal fricative

The feature theory shown in (1) fails to distinguish between palatalized postalveolar [ʃj ʧj] and prepalatal [ɕ tɕ]. This issue has been debated in the phonetic literature, notably by Dogil (1990), Halle and Stevens (1997) and Żygis and Hamann (2003). Wierzchowska (1971) and Dogil (1990) note that [ʃ Ʒ ʧ ʤ ʃj Ʒj ʧj ʤj] are pronounced with lip protrusion, which gives them a characteristic hushing quality that distinguishes them from [ɕ ʑ tɕ ʥ]. Sidestepping the exact nature of the relevant phonetic property, I will use the following segment inventory constraints:

-

(3)

-

a.

*[tɕ]: No hissing prepalatals, that is, *[tɕ ʥ ɕ ʑ].

-

b.

*[ʧ]: No hushing postalveolars, that is, *[ʧj ʤj ʃj Ʒj ʧ ʤ ʃ Ʒ].

-

a.

In contrast to the consonantal system, the vocalic system of Polish is simple. It includes the high vowels [i ɨ u],Footnote 3 the mid [ε ɔ] and the low [a].Footnote 4 The only complication is that Polish has yers, the renowned Slavic vowels, which exhibit an alternation between e [ε] and zero, as in bez ‘lilac’ (nom.sg.) – bz+y (nom.pl.).

Analyzing yers is a perennial problem of Polish phonology. Rubach’s (2016) study of the yers has been carried out in the framework of Stratal OT, so it connects with the analysis pursued here in a seamless way.

Rubach (2016) turns around the classic analysis of yers (Gussmann 1980; Rubach 1984) and argues that, first, Yer Deletion precedes Yer Vocalization and, second, Yer Deletion is context-sensitive while Yer Vocalization is context-free. Yer Deletion takes place in a CV context, meaning before a single consonant followed by a full vowel.Footnote 5 Yers that have not been deleted ‘vocalize’ context-freely and become the regular vowel [ε]. This is illustrated in (4), where I look at the derivation of bz+y ‘lilac’ (nom.pl.) and bez (nom.sg.). The yer is transcribed as the capital letter E.

-

(4)

-

a.

Yer Deletion //bEz+ɨ//Footnote 6 → [bzɨ]

-

b.

Yer Vocalization //bEz// → [bεs]

-

a.

In (4a), the yer is followed by a consonant and a vowel, and hence deletes. This context does not occur in (4b), so Yer Deletion is mute and, consequently, the yer vocalizes. Rubach (2016) argues that Yer Deletion takes place at level 2 while Yer Vocalization happens at level 3. Looking at the examples in (4), the inputs to level 3 are the structures /bzɨ/ and /bEz/. The former has no yer any more, so [bzɨ] is the final output. The latter vocalizes its yer and surfaces as [bεs], where //z// → [s] is an effect of Final Devoicing.

A further question is what the symbol //E// actually stands for. It cannot be a regular vowel [ε] because //ε// contrasts with //E// in that the deletion is unpredictable, as the following minimal pairs show.

-

(5)

bez [bεs] ‘meringue’ (gen.pl.)

–

bez+y [bεzɨ] (nom.pl.)

bez [bεs] ‘lilac’ (nom.sg.)

–

bz+y [bzɨ] (nom.pl.)

kier [kjεr] ‘hearts’ (nom.sg.)

–

kier+y [kjεrɨ] (nom.pl.)

kier [kjεr] (gen.pl.)

–

kr+y [krɨ] ‘icefloats’

The conclusion is that the yer ε and the regular vowel ε must be distinct in terms of their underlying representation. There is voluminous literature on how this distinction should be made.Footnote 7 The analysis in Rubach (2016) builds on the idea of floating segments. Specifically, the yer ε differs from the regular vowel ε by lacking a mora. Yer Vocalization is therefore a process that inserts a mora, making the yer ε, transcribed //E//, indistinguishable from the regular vowel ε.

1.2 Theoretical background: Derivational Optimality Theory

Derivational OT (Rubach 1997, 2011, 2016) is a version of Stratal OT (Kiparsky 1997, 2000, 2015; Bermúdez-Otero 1999, 2007, 2018). It is different from Stratal OT in one respect only: the assumption is that the grammar by default has four levels or strata. Stratal OT recognizes three levels/strata: the stem level, the word level and the postlexical level. Derivational OT adds a fourth level: the clitic level that is placed between the word level and the postlexical level.

The stem level encompasses the root and level 1 affixes. The word level enlarges the domain of analysis by adding level 2 affixes to the structures derived at the stem level. The determination which affixes are level 1 and which are level 2 is a language-specific matter. Similarly, languages may differ in their understanding of what constitutes a clitic structure. For example, Rubach (2016) argues that prefixes in Polish have the status of clitics,Footnote 8 hence prefix plus word structures are analyzed at level 3. The postlexical level, level 4, covers the domain of the utterance, analyzing processes that apply across word boundaries. The input to level 1 is the underlying representation, the input to level 2 is the optimal output from level 1, the input to level 3 is the winner from level 2, and the winner from level 3 is the input to level 4. In effect then, the architecture of Derivational OT is cyclic because the derivation proceeds from smaller domains to progressively larger domains: stem → word → clitic phrase → utterance. There is an obvious and actually intended similarity between Derivational OT and Lexical Phonology (Kiparsky 1982; Booij and Rubach 1987). Like in Lexical Phonology, at each cycle constraints can look at the structure derived in the previous cycle. However, unlike in Lexical Phonology, there is no prohibition to change the representations derived in an earlier cycle. Constraints are the same at all levels but their ranking may be different. The principle of reranking minimalism (Rubach 2000b) makes sure that reranking of the constraints occurs only if required by compelling analytical need. In sum, the grammar is understood as a system of four levels that are connected serially. Each level constitutes an OT ‘miniphonology,’ which means that it has its own inputs and constraint ranking. The Standard OT’s principle of strict parallelism (simultaneous evaluation, no derivational steps) holds inside a level but not across levels since, as just explained, levels are ordered serially.

From the point of view of OT, Slavic Palatalization is driven by markedness constraints that are individualized with regard to the trigger.Footnote 9

-

(6)

a. PAL-i

A consonant and a following high vowel must agree in [±back].

b. PAL-e

A consonant and a following mid vowel must agree in [±back].

c. PAL-Glide

A consonant and a following glide must agree in [±back].

PAL constraints mandate agreement in the feature [±back], so, for example, PAL-i is violated by the output [Ci] because the consonant is hard, i.e. [+back], while the vowel is front, i.e. [-back]. This violation can be removed in two ways. First, the consonant can undergo Palatalization, Ci → Cji, or the vowel can undergo Retraction, Ci → Cɨ, where [ɨ] is a [+back] vowel in terms of featural classification.

The architecture of OT requires that markedness constraints, here the constraints in (6), be controlled in their operation by faithfulness constraints. The relevant constraints evaluate the occurrence of [-back] and [+back] vowels as well as reflect the traditional bifurcation in Slavic languages into ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ consonants expressed as the opposition of [+back] for hard consonants and [-back] for soft consonants (Rubach 2003).

-

(7)

a. IDENT-C[+back]

[+back] on the consonant in the input must be preserved on

a correspondent of that consonant in the output.

b. IDENT-C[-back]

[-back] on the consonant in the input must be preserved on

a correspondent of that consonant in the output.

c. IDENT-V[-back]

[-back] on the vowel in the input must be preserved on a

correspondent of that vowel in the output.

d. IDENT-V[+back]

[+back] on the vowel in the input must be preserved on a

correspondent of that vowel in the output.Footnote 10

Palatalization as a strategy of conflict resolution is grounded in phonetics, both articulatory and acoustic. Kochetov (2016) points out that fronting and raising of the tongue body is in conflict with gestures that articulators need to execute to produce consonants with various places and manners of articulation. He further argues that the sequence of a consonant plus a front vowel or a glide is both acoustically and perceptually problematic “as front vowels tend to obscure phonetic cues to place of articulation and induce affrication, ultimately leading to perceptual confusion” (Kochetov 2016:4, see also Ohala 1978; Kawasaki 1982; Guion 1996).

This article analyzes Palatalization of velar consonants in Polish, with a focus on the surface k g → kjgj Palatalization. To keep the presentation within manageable bounds, I look at the operation of PAL-e and ignore PAL-i.Footnote 11 This operation manifests itself in two ways that appear to be contradictory.

-

(8)

a. Phonemic Velar

Palatalization k g x → ʧ ʤ ʃ /—ε

Example: ryk [k] ‘scream’ (N) – rycz+e+ć [ʧε] ‘to scream’

b. Surface Velar

Palatalization k g → kj gj /—ε

Example: cukier [kjε] ‘sugar’ (nom.sg.) – cukr+u [k] (gen.sg.)

There are two kinds of Palatalization that I dub Phonemic Velar Palatalization (8a)Footnote 12 and Surface Velar Palatalization (8b). The former makes profound changes by turning velars into strident coronals, k g → ʧ ʤ. The latter executes a minor alteration turning velars into prevelars, k g → kjgj.

In the case of PAL-e, the repair of the violation in [Cε] is implemented as Palatalization, schematically, //Cε// → [Cjε], rather than as Vowel Retraction. The reason is that Vowel Retraction acting on /ε/ as the input would derive schwa, ε → ə / C[+back]—, like we have i → ɨ / C[+back]—in the case of PAL-i (see above and Appendix). This action is blocked because schwa does not exist in Polish.

To conclude, PAL-e manifests itself in Polish as Palatalization, not as Vowel Retraction, a generalization that is expressed by the ranking of IDENT-V[-back] higher than PAL-e and IDENT-C[+back]. In what follows, I will not consider Vowel Retraction candidates such as [kə] from the input /kε/.Footnote 13

2 Phonemic Velar Palatalization

As noted in (8), velars palatalize in two different ways that I call Phonemic Velar Palatalization (k g x → ʧ ʤ ʃ) and Surface Velar Palatalization (k g → kjgj). This section looks at the former type of Palatalization in an effort to disentangle the two types of changes.

-

(9)

k → ʧ

ryk [k] ‘scream’ (N)

rycz+e+ć [ʧε] ‘to scream’

tłuk+ą [k] ‘they break’

tłucz+esz [ʧε] ‘you break’

człowiek [k] ‘man’ (nom.sg.)

człowiecz+e [ʧε] (voc.sg.)

człowiecz+ek [ʧε] (dimin.)

człowiecz+eństw+o [ʧε] ‘humanity’

g → ʤFootnote 14

mózg [sk] ‘brain’

móżdż+ek [Ʒʤε] (dimin.)

miazg+a [zg] ‘pulp’

miażdż+en+ie [Ʒʤε] ‘crushing’

x → ʃ

słuch [x] ‘hearing’

słysz+e+ć [ʃε] ‘to hear’

dach [x] ‘roof’

dasz+ek [ʃε] (dimin.)

PAL-e, which is the driver for the alternations in (9), expresses a general Palatalization process that affects not only velars but also other types of consonants, as the following sample of representative examples shows.

-

(10)

nom.sg.

voc.sg.

type of change

gloss

brat[t]

brac+ie [tɕ+ε]

tε → tɕε

‘brother’

los [s]

los+ie [ɕ+ε]

sε → ɕε

‘lot’

dzwon [n]

dzwon+ie [ɲ+ε]

nε → ɲε

‘bell’

chłop [p]

chłop+ie [pj+ε]

pε → pjε

‘farmer’

cham [m]

cham+ie [mj+ε]

mε → mjε

‘cad’

The outputs of Palatalization before ε in (10) are invariably the phonetically soft (that is, [-back]) consonants. This is expected as Palatalization spreads the feature [-back] from /ε/ to the consonant. Unexpectedly, however, the outputs given earlier in (9) are the hard (that is [+back]) consonants: [ʧ ʤ ʃ].

Since PAL-e spreads [-back], the outputs must be the soft [ʧj ʤj ʃj]. The derivation of the hard [ʧ ʤ ʃ] is an effect of an independent process that I call Hardening (HARD). In terms of OT, Hardening is a segment inventory constraint.

-

(11)

HARD [ʧ ʤ ʃ Ʒ] must be hard (that is, [+back]).

HARD is a well-known generalization in Slavic languages (Rubach 2003). The details are different in different languages, for example, in Russian [ʃ Ʒ] are hard but [ʧ] is soft (Avanesov 1968).

The co-existence of PAL-e and HARD in a single language creates an analytical problem for Standard OT. PAL-e requires agreement in [-back] between the consonant and [ε] while HARD bans [-back] stridents. The contradiction is solved by assuming that PAL-e and HARD operate on different levels of derivation, an analysis that is afforded by Derivational OT. Specifically, PAL-e, but not HARD, is active at level 1, so PAL-e is ranked high while HARD is bottom-ranked. At level 2, HARD is reranked above PAL-e, and, consequently, [ʧjε ʤjε ʃjε Ʒjε] must yield to [ʧε ʤε ʃε Ʒε], even though these outputs violate PAL-e.

Given the input //k+ε//, as in rycz+e+ć [rɨʧ+ε+tɕ] ‘to scream’, a verb derived from ryk ‘scream’, the analysis must make sure that //kε gε xε// change into /ʧj ʤj ʃj/, and not into some other segments. In particular, it is necessary to exclude /kjε gjε xjε/, which satisfy PAL-e by sharing [-back]. The desired effect is achieved by ranking as undominated the segment inventory constraints in (12).

-

(12)

-

a.

*kj: Don’t be kj

-

b.

*gj: Don’t be gj

-

c.

*xj: Don’t be xj.

-

a.

Since, given the ranking, /kjε gjε xjε/ are not viable winners in the evaluation driven by PAL-e, the query is to what segments the inputs //kε gε xε// will change. The default would be /tjε djε sjε/ as coronals are less marked than labialsFootnote 15 and anteriors are better than posteriors. However, the facts of Polish show otherwise. In particular, palatalized coronals are preferably posterior (Rubach 2003), a generalization that is expressed as the following segment inventory constraint.

-

(13)

Posteriority (POSTER) Palatalized coronals must be posterior ([-anterior]).

That is, palatalized coronals must be [-anter]. This is exactly what we find in Slovak, where [tj] is not just palatalized but also [-anter], which is marked as a minus underneath the t. However, posterior t is not the desired output of Phonemic Velar Palatalization. We need to make sure that the outputs are strident consonants, //k g x// → /ʧj ʤj ʃj/. This is effected by Stridency (Rubach 2007).

-

(14)

Stridency (STRID) Palatalized coronals must be [+strident].

The derivation //k g x// → /ʧj ʤj ʃj/ at level 1 is almost ready. The final step is to ensure that posterior stridents are the hushing stridents [ʧj ʤj ʃj] and not the hissing stridents [tɕ ʥ ɕ]. The desired effect is achieved by ranking the segment inventory constraint *[tɕ ʥ ɕ] over *[ʧj ʤj ʃj], which tips the evaluation towards the hushing stridents. Lastly, turning dorsals into coronals violates IDENT-Dor.

-

(15)

IDENT-Dor

The node DORSAL on the input segment must be preserved

on a correspondent of that segment in the output.

The foregoing discussion is summarized in all essential points by looking at the evaluation of rycz+e+ć //rɨk+ ε+tɕ// → [rɨʧ+ε+tɕ] ‘to scream’, a verb derived from ryk ‘scream’. I look at the relevant fragment of the word.

-

(16)

Level 1 //kε// → /ʧjε/

*kj

ID-V[-bk]

PAL-e

POSTER

STRID

*[tɕ]

*[ʧj]

ID-Dor

ID-C[+bk]

HARD

a. kε

*!

b. kjε

*!

*

c. tjε

*!

*

*

*

d. tjε

*!

*

*

e. tɕε

*!

*

*

f. ʧəFootnote 16

*!

*

☞

g. ʧjε

*

*

*

*

h. ʧε

*!

*

*

Obedience to PAL-e, like to any other Palatalization constraint, produces a soft [-back] consonant, which violates IDENT-C[+back]. The derivation is completed at level 2, where the [-back] stridents /ʧj ʤj ʃj/ are turned into the phonetically attested [+back] consonants through the action of HARD that is reranked to an undominated position.

-

(17)

Level 2 /ʧjε/ → [ʧε]

HARD

IDENT-V[-back]Footnote 17

PAL-e

a. ʧjε

*!

☞

b. ʧε

*

c. ʧə

*!

Coronal inputs, such as brat ‘brother’ – brac+ie [bratɕε] (voc.sg.) take a different derivational path from velar inputs. The problem is how to guarantee that //t// changes to [tɕ] and not to [ʧj], as we see in the velar input in (16). To achieve the correct result, we need to rerank the segment inventory constraints, as shown below.

-

(18)

Level 1: *[tɕ] ≫ *[ʧj] versus Level 2: *[ʧj] ≫ *[tɕ]

At level 1, //brat+ε// palatalizes to /bratjε/ but does not undergo the enhancement operation conducted by POSTER and STRID, or else /tj/ would end up as [ʧj]. The soft dental /tj/ is kept in place by faithfulness constraints.

-

(19)

a. IDENT[+anter]

[+anterior] on the input segment must be preserved

on a correspondent of that segment in the output.

b. IDENT[-strid]

[-strident] on the input segment must be preserved on

a correspondent of that segment in the output.

These IDENT constraints outrank POSTER and STRID at level 1. They block tj → ʧj, but are mute on k → ʧj. The reason is that, as noted earlier, [±anter] and [±strid] are dependents of CORON, so they are mute on velar inputs.

The spell-out operation, /tj/ → [tɕ] takes place at level 2, where we witness the following rerankings. Importantly, the default posterior segment is now [tɕ] rather than [ʧj].

-

(20)

Level 1: IDENT[+anter], IDENT[-strid] ≫ POSTER, STRID versus

Level 2: POSTER, STRID ≫ IDENT[+anter], IDENT[-strid]

Level 1: *[tɕ] ≫*[ʧj] versus Level 2: *[ʧj] ≫ *[tɕ]

The derivation of brac+ie ‘brother’ (voc.sg.) continues as follows.

-

(21)

Level 2 /bratjε/ → [bratɕε]

POSTER

STRID

IDENT[+anter]

IDENT[-strid]

*ʧj

*tɕ

a. bratjε

*!

*

b. bratjε

*!

*

c. braʦjε

*!

*

d. braʧjε

*

*

*!

☞

e. bratɕε

*

*

*

Finally, the operation of PAL-e is restricted to derived environments (DE, henceforth) in the sense that the consonant and the /ε/ must span a morpheme boundary. This condition is fulfilled by the examples in (9) and (10) but not by those in (22) below. Morpheme-internal //Cε// remains unaffected and surfaces as [Cε] in violation of PAL-e. This generalization extends to all types of consonants, not just to dorsals.

-

(22)

a. Dorsals:

kelner [kε] ‘waiter’

b. Coronals:

teść [tε] ‘father-in-law’

gem [gε] ‘game’

deszcz [dε] ‘rain’

chełp+i+ć się [xε] ‘boast’

ser [sε] ‘cheese’

c. Labials:

berł+o [bε] ‘scepter’

pewien [pε] ‘sure’

wesoł+y [vε] ‘happy’

It is unclear how the DE restriction can be built into an OT analysis and I will not pursue this issue here.Footnote 18 One way would be to make reference to a morpheme boundary in the statement of a given PAL constraint. This approach is problematic in three ways. First, Rubach (1984) has shown that Palatalization in all contexts, not just before e, may carry a DE restriction. Translated into the OT framework, this observation would mean that DE needs to be written into three separate constraints: PAL-e, PAL-i and PAL-Glide. Second, the founding assumption of OT is that constraints are universal, so there is no sense in which PAL-e is a Polish constraint. For example, PAL-e belongs just as much to Russian phonology as it does to Polish phonology. Writing DE into the statement of PAL-e would make the prediction that the DE restriction holds for Russian, like it does for Polish. The prediction is wrong because PAL-e freely applies morpheme-internally in Russian, as the following closely minimal contrasts show.

-

(23)

Russian

Polish

gloss

tekst [tjεkst]

tekst [tεkst]

‘text’

serdc+e [sjεrtʦε]

serc+e [sεrʦε]

‘heart’

hokkej [xɔkjεj]

hokej [xɔkεj]

‘hockey’

I conclude that the putative DE-PAL-e would not be able to deliver the correct results in Russian.

The third reason against building DE into particular PAL constraints stems from the observation that the same constraint in the same language can act as a DE generalization at one level but not at another level. This is what happens in the case of PAL-Glide. It is limited to DE at level 1 but not at level 2, where it applies morpheme-internally. I discuss this issue in Sect. 3.

The problems with the DE condition are eliminated if DE is divorced from particular PAL constraints and is stated as a constraint in its own right.

-

(24)

DE-PAL: A [-back] consonant and a front vowel/glide must span a morpheme boundary.

DE-PAL is subject to language-specific ranking, like any other constraint.Footnote 19 Similarly, like other constraints, it can be reranked between levels. In Polish, the restriction of PAL-e to derived environments means that the ranking is DE-PAL ≫ PAL-e. In Russian, the ranking is reversed, PAL-e ≫ DE-PAL, meaning that morpheme-internal palatalization is valued more highly than obedience to DE-PAL. The role of DE-PAL in Polish is illustrated by looking at the word seks ‘sex’ occurring in the loc.sg., whose suffix is //ε//. The surface representation contains unpalatalized [s] morpheme-internally and prepalatal [ɕ] at a morpheme boundary: //sεks+ε// → [sεkɕ+ε]. The evaluation is shown in (25), where I look at the interaction between DE-PAL and PAL-e, ignoring the constraints that make sure that the output is the prepalatal [ɕ] rather than the palatalized [sj].

-

(25)

//sεks+ε// → [sεkɕ+ε]

DE-PAL

PAL-e

IDENT-C[+back]

a. sεks+ε

**!

b. ɕεkɕ+ε

*!

**

☞ c. sεkɕ+ε

*

*

Candidate (25b) violates DE-PAL as there is no morpheme boundary between [ɕ] and [ε] in the root morpheme. This problem is repaired by candidate (25c) that leaves morpheme-internal [s] unpalatalized, so there is no violation of DE-PAL.

The question is what protects morpheme-internal sequences of a soft consonant and a front vowel from being eliminated in order to satisfy DE-PAL. These are the morphemes that have underlying soft consonants that come historically from the time when PAL-e was not constrained by DE and applied across the board (Rubach 1984). The answer is that the potential adverse action of DE-PAL is thwarted by IDENT-C[-back] that outranks DE-PAL. Thus, there is no danger that, for example, underlying //ɕεrp//, sierp ‘sickle’, can lose its palatalization because the consonant and [ε] are in the same morpheme and hence violate DE-PAL.

-

(26)

//ɕεrp// = [ɕεrp] (no change)

IDENT-C[-back]

DE-PAL

☞ a. ɕεrp

*

b. sεrp

*!

The interaction between DE-PAL and PAL-Glide mentioned above creates no difficulty (see the next section). At level 1, DE-PAL ≫ PAL-Glide ensures that the candidate respecting DE is the winner. At level 2, the constraints are reranked, so PAL-Glide has jurisdiction not only at morpheme boundaries but also morpheme-internally. As will be shown in Sect. 4, DE-PAL makes sense not only for present day synchronic analysis but also for diachronic analysis because it permits to view historical change as constraint reranking.

A reviewer draws my attention to the fact that DE-PAL can be satisfied by depalatalizing a morpheme-internal consonant, as shown by the candidate [sεrp] in (26b). This option is closed in Polish by the ranking IDENT-C[-back] ≫ DE-PAL. The reverse ranking, DE-PAL ≫ IDENT-C[-back] would lead to depalatalization. This is exactly what we find in the history of Ukrainian.Footnote 20 The word cited below means ‘winter’.

-

(27)

Polish [ʑim+a] Russian [zjim+a] Ukrainian [zɨm+a]

There is no doubt that the historical source is the form containing [i] and palatalized [zj], as in Modern Russian. That is, [zɨma] with [ɨ] and hard [z] is a Ukrainian innovation (Shevelov 1979). The innovation can be readily accounted for if DE-PAL outranks IDENT-C[-back] and PAL-i is ranked above IDENT-V[-back].

-

(28)

//zjim+a//Footnote 21 → [zɨm+a]

DE-PAL

PAL-i

IDENT-C[-back]

IDENT-V[-back]

a. zjim+a

*!

b. zim+a

*!

*

☞ c. zɨm+a

*

*

Recall that PAL-i can be satisfied either by Palatalization, Ci → Cj, or by Vowel Retraction, Ci → Cɨ, as in either case the consonant and the vowel agree in [±back]. DE-PAL is violated by (28a) because a palatalized consonant and a front vowel are not separated by a morpheme boundary.

The loc.sg. ending in Ukrainian is //i//, so the underlying representation of the loc.sg. form is //zjim+i//. The word illustrates the two effects of DE-PAL: Vowel Retraction morpheme-internally, i → ɨ, and Palatalization at a morpheme boundary, C → Cj.

-

(29)

//zjim+i // → [zɨmj+i]

DE-PAL

PAL-i

IDENT-C[-back]

IDENT-V[-back]

a. zjim+i

*!

b. zimj+i

*!

*

☞ c. zɨmj+i

*

*

The winner [zɨmj+i] is exactly the attested surface representation in Ukrainian. I conclude that DE-PAL as a constraint is supported not only by the absence of Palatalization morpheme-internally, as in Polish (26), but also by Depalatalization, as in Ukrainian (28)–(29).

In sum, DE effects in Palatalization are captured by DE-PAL, a new constraint. Evidence for level distinction and hence for Derivational OT is drawn from the ranking paradoxes displayed by the segment inventory constraints: *tɕ, *ʧj, POSTER and STRID.

3 Surface Velar Palatalization

The interaction between DE-PAL and PAL-e accounts for the absence of palatalization in (30), where the consonant and /ε/ occur inside one morpheme, as in ser [sεr] ‘cheese’.

-

(30)

//sεr// → [sεr]

DE-PAL

PAL-e

IDENT-C[+back]

☞ a. sεr

*

b. ɕεr

*!

*

The problem is that the DE restriction cannot account for the absence of palatalization in the instr.sg. forms in (31) below. The examples are the same words as in (10), but this time we look not only at the voc.sg. but also at the instr.sg.

-

(31)

nom.sg.

voc.sg.

instr.sg.

gloss

brat

brac+ie [tɕ+ε]

brat+em [t+εm]

‘brother’

los [s]

los+ie [ɕ+ε]

los+em [s+εm]

‘lot’

dzwon [n]

dzwon+ie [ɲ+ε]

dzwon+em [n+εm]

‘bell’

chłop [p]

chłop+ie [pj+ε]

chłop+em [p+εm]

‘farmer’

cham [m]

cham+ie [mj+ε]

cham+em [m+εm]

‘cad’

These data show that the e of the instr.sg. suffix -em does not induce Palatalization. The same is true of a few other suffixes in the declension of adjectives.

-

(32)

-

a.

Masculine declension

gen.sg.

dat.sg.

gloss

grub+ego [b+εgɔ]

grub+emu [b+εmu]

‘fat’

tłust+ego [t+εgɔ]

tłust+emu [t+εmu]

‘greasy’

Likewise (same examples):

-

b.

Feminine and neuter declension

neuter nom.sg.

feminine gen.sg.

fem/neuternom.pl.

grub+e [b+ε]

grub+ej [b+εj]

grub+e [b+ε]

tłust+e [t+ε]

tłust+ej [t+εj]

tłust+e [t+ε]

-

c.

Foreign agentive –er

boks [s] ‘boxing’ – boks+er [s+εr] ‘boxer’

tost [t] ‘toast’ – tost+er [t+εr] ‘toaster’

skan [n] ‘scan’ – skan+er [n+εr] ‘scanner’

-

a.

The absence of palatalization in (31)–(32) is puzzling because the DE condition, a consonant and a vowel spanning a morpheme boundary, is fulfilled.

It appears that the suffixes in (31)–(32) must be marked as exceptions to Palatalization, but such marking cannot be correct, as the following examples show.

-

(33)

Surface Velar Palatalization: //k+ε// → [kj+ε] and //g+ε// → [gj+ε]

a. Nouns:

nom.sg.

instr.sg.

gloss

rok [k]

rok+iem [kj+εm]

‘year’

róg [k]

rog+iem [gj+εm]

‘horn’

BUT no Surface Velar Palatalization with /x/

dach [x]

dach+em [x+εm]

‘roof’

b. Masculine adjectives:

gen.sg.

dat.sg.

gloss

wysok+iego [kj+εgɔ]

wysok+iemu [kj+εmu]

‘tall’

dług+iego [gj+εgɔ]

dług+iemu [gj+εmu]

‘long’

BUT no Surface Velar Palatalization with /x/:

głuch+ego [x+εgɔ]

głuch+emu [x+εmu]

‘deaf’

c. Likewise feminine and neuter adjectives (same examples):

neuter nom.sg.

feminine gen.sg.

fem/neuter nom.pl.

wysok+ie [kj+ε]

wysok+iej [kj+εj]

wysok+ie [kj+ε]

dług+ie [gj+ε]

dług+iej [gj+εj]

dług+ie [gj+ε]

BUT no Surface Velar Palatalization with /x/

głuch+e [x+ε]

głuch+ej [x+εj]

głuch+e [x+ε]

d. Foreign agentive –er

bank [k] ‘bank’ – bank+ier [kj+εr] ‘banker’

pomag+a+ć [g] ‘help’ – pomag+ier [gj+εr] ‘helper’

To conclude, the suffixes in (31)–(33) show a contradictory behavior: they are palatalizing for velar stops, but not for other types of consonants. Furthermore, the effect of Velar Palatalization is different from that seen before: //k g// change to [kj gj] rather than to [ʧʤ], as in ryk [k] ‘scream’ (nom.sg.) – ryk+iem [kj+ε] (instr.sg.) versus rycz+e+ć [ʧ+ε] ‘to scream’. The contradictions just outlined are resolved by Derivational OT without difficulty. The scenario is as follows.

The suffixes -em (instr.sg.), -ego (masc. gen.sg.), -emu (masc. dat.sg.), -e (neuter nom.sg.), -ej (fem. gen.sg.), -e (nom.pl.), and the foreign agentive -er are level 2 suffixes. This means that they are not available for evaluation at level 1, which accounts for the absence of palatalization at level 1 in brat+em [t+εm] ‘brother’ (instr.sg.), tłust+ego [t+εgɔ] ‘greasy’ (gen.sg.), tłust+emu [t+εmu] (dat.sg.), tost+er [t+εr] ‘toaster’, and so forth.Footnote 22

An objection can be raised that the assignment of affixes to different levels is arbitrary. This is true and it reflects different historical sources that merged in the evolution of the language. The point is that Derivational OT has the resources to give a formal account of differences in the behavior of various affixes.

A reviewer points out that Standard OT could account for the behavior of level 2 suffixes by resorting to indexed constraints (Pater 2008). This is true, for example, an Output–Output faithfulness constraint OO-IDENT-Dor could be co-indexed with the instr.sg. suffix //εm//. The drawback of this solution is that it opens the way to analyses in which potentially every affix could have a phonology of its own, which hugely weakens the restrictiveness of the theory. Derivational OT assigns the problematic suffixes to a level and they cannot choose to which constraints they wish to be available. I conclude that level assignment is a more restrictive mechanism than Standard OT’s indexed constraints and OO-faithfulness.

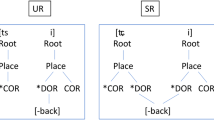

The question regarding the absence of palatalization returns at level 2, but the action of PAL-e is now severely curtailed. The curtailment is effected by the high ranking of the segment inventory constraints: *SOFT-Lab, banning palatalized labials, *SOFT-Coron, prohibiting [-back] coronals, and *xj, banning the palatalized velar fricative.

-

(34)

-

a.

Level 1: *kj *gj *xj ≫ PAL-e ≫ *SOFT-Lab, *SOFT-Coron

-

b.

Level 2: *SOFT-Lab, *SOFT-Coron, *xj ≫ PAL-e ≫ *kj *gj

-

a.

At level 1, it is more important to obey PAL-e than the segment inventory constraints against soft labials and coronals (34a), so we have Palatalization of labials and coronals, exemplified in (10), such as chłop ‘man’ – chłop+ie [pj+ε] (voc.sg.) and brat ‘brother’ – brac+ie [bratɕ+ε] (voc.sg.). At level 2, greater value is placed on obeying the segment inventory constraints in (34b) than obeying PAL-e, so Palatalization of labials, coronals and /x/ before /ε/ is blocked, as required by the data in (31)–(33).

At level 2, velar stops palatalize in a surface manner, k g → kjgj, because the option of changing /k g/ to [ʧʤ] is closed by reranking IDENT-Dor to an undominated position. In (35), I look at the evaluation of krok+iem ‘step’ (instr.sg.) at level 2. Recall that //εm// is a level 2 suffix, so it was not available on level 1.

-

(35)

Level 2 /krɔk+εm/ → [krɔkj+εm]

IDENT-Dor

PAL-e

*kj *gj

IDENT-C[+back]

a. krɔk+εm

*!

☞

b. krɔkj+εm

*

*

c. krɔʧj+εm

*!

*

The blocking effect of the reranked constraints in (34b) is illustrated by pas+em [pasεm] ‘belt’ (instr.sg.).

-

(36)

Level 2 /pas+εm/ = [pas+εm] (no change)

*SOFT-Coron

PAL-e

☞ a. pas+εm

*

b. paɕ+εm

*!

There is no danger that the high-ranked *SOFT-Coron can undo the work done by PAL-e at level 1, as in, for example, los ‘lot’ (nom.sg.) – los+ie [lɔɕ+ε] (loc.sg.), which leaves level 1 with the representation /lɔsj+ε/.Footnote 23 The integrity of the palatalized /sj/ or [ɕ] is guarded by IDENT-C[-back] that is undominated at both level 1 and level 2.

-

(37)

Level 2 /lɔsj+ε/ → [lɔɕ+ε]

IDENT-C[-back]

*SOFT-Coron

PAL-e

Spell-outFootnote 24

a. lɔsj+ε

*

*!

☞ b. lɔɕ+ε

*

c. lɔs+ε

*!

*

The relationship between DE-PAL and PAL-e is copied unchanged from level 1 to level 2, which means that the ranking is DE-PAL ≫ PAL-e. The effect of the ranking is that the actual jurisdiction of PAL-e is limited to derived environments. This is exactly correct, as morpheme-internally, we find [kε gε] rather than [kjε gjε].

-

(38)

poker [kε] ‘poker’

legend+a [gε] ‘legend’

kelner [kε] ‘waiter’

geograf+ia [gε] ‘geography’

kefir [kε] ‘kefir’

geometr+ia [gε] ‘geometry’

hokej [kε] ‘hockey’

gest [gε] ‘gesture’

The constraint system predicts, correctly, that, for example, poker ‘poker’ is pronounced with [kε] while rok+iem ‘year’ (instr.sg.) has the palatalized [kjε], as the following evaluations show.

-

(39)

i. Level 2 /pɔkεr/ = [pɔkεr] (no change)

IDENT-Dor

DE-PAL

PAL-e

IDENT-C[+back]

☞ a. pɔkεr

*

b. pɔkjεr

*!

*

c. pɔʧjεr

*!

*

ii. Level 2 /rɔk+εm/ → [rɔkj+εm]

IDENT-Dor

DE-PAL

PAL-e

IDENT-C[+back]

a. rɔk+εm

*!

☞ b. rɔkj+εm

*

c. rɔʧj+εm

*!

*

Recall that DE-PAL requires that a soft consonant and a front vowel span a morpheme boundary, a demand that is fulfilled in (39iib), [rɔkj+εm], but not in (39ib), [pɔkjεr].

The consequence of limiting PAL-e to derived environments, DE-PAL ≫ PAL-e, is that morpheme-internal [kj gj] are not derivable from //k g// any more and hence must be underlying segments, as the following sample of examples illustrates.

-

(40)

kiedy [kjεdɨ] = //kjεdɨ// ‘when’

zgiełk [zgjεwk] = //zgjεwk// ‘turmoil’

kierat [kjεrat] = //kjεrat// ‘treadmill’

giemz+a [gjεmz+a] = //gjεmz+a// ‘chamois’

kier [kjεr] = //kjεr// ‘hearts’

giermek [gjεrmεk] = //gjεrmεk// ‘page’

Similarly as in (26) and (37), DE-PAL cannot undo the palatalization on the input //kjε// and //gjε// since DE-PAL is kept in check by IDENT-C[-back].

-

(41)

Level 2 /kjεdɨ/ = [kjεdɨ] (no change)

IDENT-Dor

IDENT-C[-back]

DE-PAL

PAL-e

☞

a. kjεdɨ

*

b. kεdɨ

*!

*

c. ʧjεdɨ

*!

There are two points that merit underscoring. First, the occurrence of [k g] versus [kj gj] cannot be predicted, as in poker [pɔkεr] ‘poker’ – kier [kjεr] ‘hearts’. Therefore, [k] versus [kj] must be encoded in the underlying representation: //pɔkεr// and //kjεr//. Second, the analysis upholds Kiparsky’s (1993) observation that the derived environment restriction can hold not only at the first level of derivation but also at later levels.Footnote 25 Specifically, PAL-e exhibits the DE limitation at both level 1 and level 2, as we have just seen. PAL-Glide to which we now turn substantiates a different theoretical point.

The action of PAL-Glide is limited to derived environments at level 1 but not at level 2, which shows that it would be ill-advised to write the DE restriction into the statement of PAL-Glide itself. The correct analysis treats the DE restriction as a constraint that I have dubbed DE-PAL. The ranking DE-PAL ≫ PAL-Glide postulated for level 1 restricts PAL-Glide to derived environmentsFootnote 26 while the reranking to PAL-Glide ≫ DE-PAL postulated for level 2 lifts this restriction. The details of the analysis ensue below.

The examples below illustrate the so-called ‘yers’, that is, vowels that alternate with zero (recall Sect. 1.1.).

-

(42)

-

a.

Masculine nouns

nom.sg.

gen.sg.

gloss

kiep [kjεp]

kp+a [kpa]

‘fool’

cukier [ʦukjεr]

cukr+u [ʦukru]

‘sugar’

giez [gjεz]

gz+a [gza]

‘gadfly’

ogień [ɔgjεɲ]

ogn+ia [ɔgɲa]

‘fire’

-

b.

Feminine and neuter nouns

nom.sg.

gen.pl.

gloss

kr+a [kra]

kier [kjεr]

‘icefloat’

iskr+a [iskra]

iskier [iskjεr]

‘spark’

bagn+o [bagnɔ]

bagien [bagjεn]

‘swamp’

igł+a [igwa]

igieł [igjεw]

‘needle’

-

a.

As explained in Sect. 1.1 yers, transcribed //E//, are floating melodic segments at the underlying level, so Yer Vocalization is a process of mora insertion. Prior to mora insertion, the yer is a melodic segment that cannot erect a syllable itself precisely because it lacks a mora. This is exactly the structure that characterizes glides. In autosegmental theory, the glide [j], for example, is the vocalic melodic segment [i] that lacks a mora. To conclude, the yer is structurally identical to a glide and, consequently, must be treated as a glide. The difference between //j// and //E// is that //j// is a high front glide while //E// is a mid front glide. The conclusion that matters for the analysis in this article is that Palatalization caused by yers falls under the jurisdiction of PAL-Glide, and not PAL-e.

The data in (42) represent a significant generalization that I state informally in (43).

-

(43)

Yers trigger Surface Velar Palatalization: k g → kj gj /—E

This generalization is entirely exceptionless and fully productive. It extends to newly created yers, that is, to recent borrowings, as the following examples demonstrate.

-

(44)

Russian łager ‘camp’ → Polish łagier [gjεr], a yer as [ε] alternates with zero in łagr+y (nom.pl.)

English single → Polish singiel [gjεl] ‘single person’, a yer as [ε] alternates with zero in singl+e (nom.pl.)

Since, as already said, yers are formally glides, the responsibility for inducing Palatalization rests with PAL-Glide, not with PAL-e. This is fortunate because Palatalization before //E// and Palatalization before the regular vowel //ε// exhibit different behaviors. The latter, that is, PAL-e, applies in derived environments and is blocked morpheme-internally: recall the data in (33) and (38), such as rok ‘year’ (nom.sg.) – rok+iem [rɔkj+εm] (instr.sg.) versus poker [pɔkεr] ‘poker’.

In contrast, PAL-Glide applies morpheme-internally, as in kiep [kjεp] ‘fool’ (nom.sg.) – kp+a [kp+a] (gen.sg.) and ogień [ɔgjεɲ] – ogn+ia [ɔgɲ+a] (gen.sg.). Translated into the constraint system, morpheme-internal application means that PAL-Glide must outrank DE-PAL. The derivation of kiep ‘fool’ is therefore as follows.

-

(45)

Level 2 /kEp/ → [kjεp]

Yer Del

IDENT-Dor

PAL-Glide

DE-PAL

IDENT-C[+back]

a. kEp

*!

☞ b. kjEp

*

*

c. ʧjEp

*!

*

*

Recall that Yer Deletion deletes //E// if followed by a consonant and a vowel, which is not the situation in (45), so /E/ survives in the optimal candidate at level 2. The winner from level 2, /kjEp/, is the input to level 3, at which yers vocalize, that is, obtain a mora and hence become nondistinct from the regular vowel [ε]: /kjEp/ → [kjεp].

The gen.sg. form kp+a ‘fool’, from underlying //kEp+a//, loses its yer at level 2 because E is followed by a consonant (here p) and a vowel (here a). Deleting the yer violates MAX-Seg that militates against deletion.

-

(46)

Level 2 /kEp+a/ → [kp+a]

Yer Del

IDENT-Dor

PAL-Glide

DE-PAL

MAX-Seg

IDENT-C[+back]

a. kEp+a

*!

*!

☞

b. kp+a

*

c. kjp+a

*

*!

The analysis is correct as [kpa] is the attested surface form. It is worth underscoring that there is an advantage to doing Surface Velar Palatalization at level 2 rather than at level 1. The reason is that yers are deleted at level 2, which allows us to uphold the generalization that /k g/ are palatalized before yers but only before those yers that ultimately vocalize and are turned into [ε] in the surface representation.

If Surface Velar Palatalization was done at level 1, hence prior to Yer Deletion, it would be necessary to postulate a Depalatalization constraint to depalatalize the stops at level 2. That is, //kEp+a// → /kjEp+a/ at level 1 and /kjEp+a/ → /kjp+a/ → [kpa] at level 2. The Depalatalization step and the Depalatalization constraint are not necessary if Surface Velar Palatalization is executed at level 2, as proposed in this paper.

PAL-Glide operates not only at level 2 but also at level 1, as the following examples show. The suffix –ek is a diminutive morpheme.

-

(47)

root

dimin. nom.sg.

dimin. gen.sg.

gloss

bok [k]

boczek [ʧ+εk]

bocz+k+a [ʧ+k]

‘side’

mózg [sk]

móżdż+ek [ʤ+εk]

móżdż+k+a [ʃʧ+k]

‘brain’

dach [x]

dasz+ek [ʃ+εk]

dasz+k+a [ʃ+k]

‘roof’

The diminutive suffix –ek contains a yer because e alternates with zero in (47). The representation is therefore //Ek// and the palatalization effects are the action of PAL-Glide, not of PAL-e. The point is that the changes driven by PAL-Glide and the associated constraints are different at level 1 and at level 2.

-

(48)

Level 1: k g x → ʧ ʤ ʃ/ — E, as shown in (47)

Level 2: k g → kj gj / — E, as shown in (42)

Further, the operation of PAL-Glide at level 1 leads to opacity in the surface representation. We see this in the gen.sg. forms in (49), for example, bocz+k+a, the gen. sg. of bocz+ek ‘side’ (dimin.).

-

(49)

Level 1: //bɔk+EK+a// → /bɔʧj+Ek+a/

Level 2: /bɔʧj+Ek+a / → [bɔʧka]

The trigger of Palatalization is not present in the surface representation, so the representation is opaque. In contrast, the outcomes produced by PAL-Glide at level 2 are fully transparent: we see [kj gj] only in the forms that have the trigger of Palatalization present in the surface representation, so the //k// is palatalized in kiep [kjεp] ‘fool’ (nom.sg.), but not in kp+a [kpa] (gen.sg.): //kEp// → [kjεp], with k → kj at level 2, but //kEp+a// → [kpa], with [k] at level 2.

It should also be noted that PAL-Glide is constrained by DE-PAL at level 1, that is, its jurisdiction is limited to derived environments, as in bocz+ek, //bɔk+EK// → /bɔʧj+Ek/. It is imperative that morpheme-internal structure is not within the reach of PAL-Glide because morphemes such as kiep //kEp// ‘fool’ and cukier //ʦukEr// ‘sugar’ must escape the //k// → /ʧj/ Palatalization and must emerge unscathed from level 1: /kEp/, not */ʧjEp/ and /ʦukEr/, not */ʦuʧjEr/. At level 2, on the other hand, the objective is reversed: PAL-Glide must be able to look into morphemes: /kEp/ → /kjEp/ and /ʦukEr/ → /ʦukjEr/.

The range of inputs to PAL-Glide is different at level 1 and level 2. At level 1, PAL-Glide affects not only //k g// but also //x//, as seen in (47): //bɔk+Ek// → /bɔʧjEk/ ‘side’ (dimin.) and //dax+Ek// → /daʃjEk/ ‘roof’ (dimin.). At level 2, PAL-Glide applies to //k g//, but not to //x//, as shown by cukier [ʦukjεr] ‘sugar’, with soft [kj] but wicher [vjixεr] ‘gale’, with hard [x].

The activity of PAL-e and PAL-Glide is different at different levels. PAL-e loses force at both the clitic phrase level (level 3) and the postlexical level (level 4). That is, the outputs are selected as optimal even if they violate PAL-e.

-

(50)

-

a.

PAL-e at level 3: clitics

Tak powiedział+em [w+εm] ‘I said so’ OR Tak+em [tak+εm] powiedział ‘So I said’ (clitic movement)

przed+egzaminacyjny [d+ε] ‘pre-examination’, not *[ʥ+ε] or *[dj+ε]

przed egzaminem [d ε] ‘before the examination’, not *[ʥ+ε] or *[dj+ε], that is, no Palatalization of any kind

-

b.

PAL-e at level 4: sentences

krok Ewy [krɔk εvɨ] ‘Eva’s step’, not *[krɔʧ εvɨ] or *[krɔkj εvɨ],

that is, no Palatalization of any kind

-

a.

The net result is that PAL-e produces no change at levels 3 and 4. This means that the ranking of the constraints is different from that at level 2. Specifically, IDENT-C[+back] is now ranked above PAL-e.

-

(51)

Level 2: PAL-e ≫ IDENT-C[+back]Footnote 27

Level 3 (and Level 4): IDENT-C[+back] ≫ PAL-e

In contrast to PAL-e, PAL-Glide is fully active at both level 3 and level 4.

-

(52)

a. PAL-Glide at level 3

b. PAL-Glide at level 4

przed+jedzeniowy [dj+j] ‘pre-eating’

sklep Janka [pj j] ‘Janek’s store’

przed jedzeniem [dj+j] ‘before eating’

skecz Janka [ʧj j] ‘Janek’s sketch’

krok jej [kj j] ‘her step’

krok Janka [kj j] ‘Janek’s step’

duch jej [xj j] ‘her spirit’

duchJanka [xj j] ‘Janek’s spirit’

brat jej [tj j] ‘her brother’

brat Janka [tj j] ‘Janek’s brother’

skecz jej [ʧj j] ‘her sketch’

sklep jej [pj j] ‘her store’

This is a very different situation from that found at level 2: PAL-Glide applies to all consonants in an unconstrained way. The generalization is captured by reranking PAL-Glide to an undominated position.

-

(53)

Level 2: *SOFT-Lab, *SOFT-Coron, *xj ≫ PAL-Glide ≫ IDENT-C[+back]

Levels 3 and 4: PAL-Glide ≫ *SOFT-Lab, *SOFT-Coron, *xj, IDENT- C[+back]

To conclude, as (53) shows, a large number of segment inventory constraints determining admissible inventories are ranked differently in the word domain (level 2) and in the phrase domain (levels 3 and 4). The differences in ranking cannot be derived from Standard OT’s opacity theories since these theories are not equipped to handle such differences. I conclude that the segment inventory constraints in (53) constitute an argument for levels and hence for Derivational OT.

In the following section, I look at PAL-e from a historical perspective, focusing on k g → kjgj, the effects of Surface Velar Palatalization.

4 A historical perspective

This section pursues the history of Surface Velar Palatalization from Old Polish (10th–15th c.), through Middle Polish (16th–18th c.) to Modern Polish (19th c. – present). Of interest are the concatenations of k, g and e, occurring inside morphemes and across morpheme boundaries.

Historical grammars of Polish concur: there was no Surface Velar Palatalization in Old Polish. Długosz-Kurczabowa and Dubisz (2006:147) cite zgiełk ‘turmoil’ and kiełbasa ‘sausage’ as examples of words pronounced with hard [kε], [gε] in Old Polish. The hard pronunciation was also true in contexts in which [ε] was a vocalized yer, as in the following examples (Długosz-Kurczabowa and Dubisz 2006:147).

-

(54)

kieł ‘cuspid’ (nom.sg.) – kł+y [nom.pl.), where kieł was pronounced [kεł],

//kEł//Footnote 28 → [kεł] by Yer Vocalization

okn+o ‘window’(nom.sg.) – okien (gen.pl.), where okien was pronounced

[ɔkεn], //ɔkEn// → [ɔkεn] by Yer Vocalization ogień ‘fire’ – ogn+ie (nom.pl.), where ogień was pronounced [ɔgεɲ],

//ɔgEɲ// → [ɔgεɲ] by Yer Vocalization (Stieber 1973:68)

The absence of Surface Velar Palatalization morpheme-internally raises the question of whether the process might have been limited to derived environments, which would explain its absence morpheme-internally. Limitation to derived environments is commonplace in Slavic phonology (see Rubach 1984). The answer is negative: Surface Velar Palatalization did not apply in derived environments. This is the conclusion of Stieber (1973:67–68), who evaluated scribal practices in Old Polish.

-

(55)

język ‘tongue’ (nom.sg.) – język+em [k+εm] (instr.sg.)

Likewise:

drug+ego [g+εgɔ] ‘second’ (masc. gen.sg.)

nyebyesk+emu [k+εmu] ‘blue’(masc. dat.sg.)

słodk+ey [k+εj] ‘sweet’ (fem. gen.sg.)

wissok+e [k+ε] ‘tall’ (fem./neuter nom.pl.)

The generalization is clear: [kj gj] did not exist as phonetic segments in Old Polish.Footnote 29 The absence of [kj gj] means that the segment inventory constraints *kj, *gj were undominated and blocked Palatalization from all PAL constraints.

According to Stieber (1973) and Długosz-Kurbaczowa and Dubisz (2006), this situation changed in Early Middle Polish (16th c.): soft [kj gj] started occurring in the very same contexts in which there were hard [k g] in Old Polish, so the examples in (55) would now look as follows.

-

(56)

język ‘tongue’ (nom.sg.) – język+iem [kj+εm] (instr.sg.)Footnote 30

Likewise:

drug+iego [gj+εgɔ] ‘second’ (masc. gen.sg.)

niebiesk+iemu [kj+εmu] ‘blue’ (masc. dat.sg.)

słodk+iej [kj+εj] ‘sweet’ (fem. gen.sg.)

wysok+ie [kj+ε] ‘tall’ (fem./neuter nom.pl.)

Surface Velar Palatalization applied not only at morpheme boundaries (56) but also morpheme-internally.

-

(57)

Old Polish

Middle Polish

[kεdɨ]

[kjεdɨ]

kiedy ‘when’

[zgεɫk]

[zgjεɫk]

zgiełk ‘turmoil’

[kεɫbasa]

[kjεɫbasa]

kiełbasa ‘sausage’

[kεɫ]

[kjεɫ]

kieł ‘cuspid’

[gεz]

[gjεs]

giez ‘gadfly’

In terms of the constraint system, the change between Old Polish and Middle Polish is a matter of reranking of the segment inventory constraints *kj *gj.

-

(58)

Old Polish:

*kj *gj ≫ PAL-e

Middle Polish:

PAL-e ≫ *kj *gj

The word kiedy ‘when’ serves as an example illustrating the changes.

-

(59)

i. Old Polish /kεdɨ/ = [kεdɨ] (no change)

*kj *gj

PAL-e

IDENT-C[+back]

☞ a. kεdɨ

*

b. kjεdɨ

*!

*

ii. Middle Polish /kεdɨ/ → [kjεdɨ] (Surface Velar Palatalization)

PAL-e

*kj *gj

IDENT-C[+back]

a. kεdɨ

*!

☞ b. kjεdɨ

*

*

Surface Velar Palatalization was perfectly productive in Middle Polish and it applied to all borrowings whose input structure had [kε] or [gε]. A sample of representative examples are cited from Sławski (1952).

-

(60)

kies+a, [kjεsa] ‘purse’, a 17th c. borrowing from Turkish kese

kieln+ia [kjεlɲa] ‘trowel’, a 16th c. borowing from German Kelle

kaszkiet [kaʃkjεt] ‘cap’, an 18th c. borrowing from French casquette

giemz+a [gjεmza] ‘chamois’, a 16th c. borrowing from German Gemse

giermek [gjεrmεk] ‘page’, a 15th c. borrowing from Hungarian gyermek

The 18th and the 19th centuries witnessed a huge influx of borrowings and the pronunciation of the foreign [kεgε] was much debated in the linguistic literature of the 19th century. For example, Jeske (1800) states explicitly that the soft pronunciation [gjε] is used in gest [gjεst] ‘gesture’, geologia [gjεɔlɔgjja] ‘geology’, geografia [gjεɔgrafjja] ‘geography’, geniusz [gjεɲjuʃ] ‘spirit’, etc. Muczkowski (1849) establishes a rule that prohibits hard g before e. Małecki (1863) concurs that g is always pronounced soft before e, as in tragedia [tragjεdjja] ‘tragedy’, algebra [algjεbra] ‘algebra’, geometria [gjεɔmεtrjja] ‘geometry’, etc. Baudouin de Courtenay et al. (1899) record soft [gjε] in, for instance, legenda [lεgjεnda] ‘legend’, gestykulacja [gjεstɨkulaʦjja] ‘gesticulation’, genialny [gjεɲjalnɨ] ‘spiritual’ and, ewangelia [εvangjεljja] ‘gospel’. Kryński (1903:308) agrees with the rule k g → kjgj before e and adds new examples: ankieta [aŋkjεta] ‘inquiry’, agenda [agjεnda] ‘agency’ and bukiet [bukjεt] ‘bouquet’. He adopts the spelling convention that soft [kj gj] are marked by the letter i that is not pronounced. This leads him to recommend, for example, the following spellings.

-

(61)

Kryński’s spelling ( 1903 :308)

today’s spelling

gloss

legienda [lεgjεnda]

legenda

‘legend’

agienda [agjεnda]

agenda

‘agency’

algiebra [algjεbra]

algebra

‘algebra’

ewangielja [εvaŋgjεljja]

ewangelia

‘gospel’

gienerał [gjεnerał]

generał

‘general’

giest [gjεst]

gest

‘gesture’

Finally, Ładoń (1920:10) mandates that “k, g before e or i must be pronounced soft as kie, gie”Footnote 31 [my translation: IR], for instance, kiefir [kjεfjir] ‘kefir’, kierat [kjεrat] ‘treadmill’, cukier [ʦukjεr] ‘sugar’, and szwagier [ʃfagjεr] ‘brother-in-law’.

The pronunciation of the foreign [kε gε] as [kjε gjε] shows that PAL-e applies productively not only at morpheme boundaries, as in krok+iem ‘step’ (instr. sg.) and rog+iem ‘horn’ (instr. sg.) but also inside morphemes. To achieve this result, PAL-e must outrank DE-PAL, so that the derived environment restriction has no force.Footnote 32

The situation just described changes in the middle of the 20th century. First, new borrowings are not assimilated by palatalizing k, g before e. Second, we witness pronunciation reversals on a huge scale.

-

(62)

New borrowings (later than 1950)

a. hard [kε]:

dysk dżokej ‘disc jockey’

keczup ‘ketchup’

marker ‘marker’

marketing ‘marketing’

karaoke ‘karaoke’

kebab ‘type of hamburger’

b. hard [gε]

gem ‘game’

genetyk+a ‘genetics’

gen ‘gene’

geriatria ‘geriatrics’

hamburger ‘hamburger’

getry ‘long socks’

The generalization is that PAL-e stopped applying morpheme-internally. Palatalization is still 100% productive at morpheme boundaries, as shown by the fact that it applies to foreign names.

-

(63)

Edynburg ‘Edinburgh’ – Edenburg+iem [gj+εm] (instr.sg.)

Sherlock Holmes – Sherlock+iem [kj+εm] Holmsem (instr.sg.)

The limitation of PAL-e to derived environments induces restructuring of underlying representations, as the following examples show.Footnote 33

-

(64)

kiedy //kεdɨ// is restructured as //kjεdɨ//

Likewise:

kier+owa+ć //kεr// → //kjεr// ‘move in a direction’

pakiet //pakεt// → //pakjεt// ‘packet’

giermek //gεrmεk// → //gjεrmεk// ‘page’

giemz+a //gεmz+a// → //gjεmz+a// ‘chamois’

higien+a //xigεn+a// → //xigjεn+a// ‘hygiene’

The representations restructure by moving the previously derivable [kjε gjε] to the underlying representation. The reason is that PAL-e, now constrained by DE-PAL, cannot derive morpheme-internal [kj gj] any longer.

In contrast, the [kj gj] derivable by PAL-Glide do not restructure as //kj gj//. The vowel is a yer, as shown by the fact that we have an e – zero alternation.

-

(65)

nom.sg.

gen.sg.

UR

gloss

[kjεp]

kp+a [kpa]

//kEp//

‘fool’

lukier [lukjεr]

lukr+u [lukru]

//lukEr//

‘frosting’

ogień [ɔgjεɲ]

ogn+ia [ɔgɲa]

//ɔgEɲ//

‘fire’

As noted in (44) in Sect. 3, Palatalization before E is 100% reliable and exceptionless. The underlying representation is therefore underspecified for the predictable [-back] feature on the velar consonant.

The historical level 2 reranking of PAL-e ≫ DE-PAL to DE-PAL ≫ PAL-e and hence the inability of producing Palatalization morpheme-internally has resulted in massive pronunciation reversals. The very same examples that the 19th c. grammarians used in order to illustrate the pronunciation [kjε gjε] are now examples for hard [kε gε].

-

(66)

Pronunciation reversals

19th c.

today

gloss

[kjεfjir]

[kefjir]

kefir ‘kefir’

[kjεlnεr]

[kεlnεr]

kelner ‘waiter’

[lεgjεnda]

[lεgεnda]

legenda ‘legend’

[gjεst]

[gεst]

gest ‘gesture’

[gjεnεraɫ]

[gεnεraw]

generał ‘general’

[intεljigjεnʦjja]

[intεljigεnʦjja]

inteligencja ‘intelligence’

[εvaŋgjεljja]

[εvaŋgεljja]

ewangelia ‘gospel’

The words in (66), for example, legend+a ‘legend’, illustrate Duke-of-York derivations (Pullum 1976), but in a diachronic rather than synchronic dimension. Sławski (1952) states that legenda is a 16th c. borrowing of the mediaeval Latin legenda ‘story of saints’. At the point of borrowing, the ge in legenda was pronounced [gε]. In 1903 exactly this word is cited by Kryński (1903) as an example of the soft [gjε] pronunciation. Today legenda is invariably pronounced with hard [gε]. Schematically:

-

(67)

16th c.

16–19thc.

today

gloss

[lεgεnda]

[lεgjεnda]Footnote 34

[lεgεnda]

‘legend’

Pronunciation reversals do not constitute a problem for a theory that distinguishes between underlying and surface representations. Looking at legenda as an example, the Latin legenda enters Polish with //gε// because [gε] is the surface representation in the 16th c., [lεgεnd+a] = //lεgεnd+a//. The pronunciation [lεgjεnda] is an effect of Surface Velar Palatalization, a rule that develops in the 16th/17th c. Since the derivation g → gj is fully predictable from Surface Velar Palatalization, the underlying representation is underspecified for Palatalization, //lεgεnd+a//. In the 20th c. Surface Velar Palatalization changes status and becomes restricted to derived environments. Consequently, it can no longer affect morpheme-internal //gε// and hence legenda starts surfacing as [lεgεnda], with hard [gε]. Some words such as giermek [gjεrmεk] ‘page’ and kiedy [kjεdɨ] ‘when’ restructured their underlying representations from //gε// and /kε// to //gjε// and //kjε//, respectively, because there were no alternations between [kj gj] and [k g]. The restructuring process was lexically diffused and proceeded in an item-by-item manner, so, for example, the restructuring occurred in giermek //gjεrmεk// ‘page’ but not in legenda //lεgεnd+a// ‘legend’. When, in the 20th c., Surface Velar Palatalization lost jurisdiction over morpheme-internal structures, underlying representations emerged as surface representations, yielding [gjεrmεk] and [lεgεnda], respectively.

These pronunciation reversals highlight a new theoretical point. Namely, they show that reversals are possible in the absence of alternations. Kiparsky’s (1973) conclusion that reversals may occur only in instances of alternation is therefore too restrictive.Footnote 35

The story of ke, ge is relevant for the understanding of the life cycle of a process (Baudouin de Courtenay 1894; Hyman 1976; Bermúdez-Otero 1999, 2007, 2013; Kiparsky 2013). The idea of the life cycle is that a phonological process starts in phonetics and, when phonologized, begins to climb up the strata of Derivational/Stratal OT, beginning with the postlexical stratum (Bermúdez-Otero 2013). At late stages in the life cycle, the process is morphologized, stops being productive and finally expires. The story of ke, ge makes two additions to this understanding of the life cycle. First, a process may begin at level 2 rather than at level 4.Footnote 36 Second, evolution of a process goes through the stage at which it develops a DE restriction. At that stage, the process is still extremely regular and exceptionless, as exemplified by Surface Velar Palatalization, but its jurisdiction has narrowed down to derived environments.

A further point that the story of ke, ge brings out is the characterization of Palatalization in terms of PAL constraints. The DE restriction has affected PAL-e but not PAL-Glide and PAL-i (see the Appendix below), which continue to apply morpheme-internally as in //kEp// → /kjEp/ ‘fool’ (and /kjEp/ → [kjεp] at level 3), //dialekt// → [djjalεkt] ‘dialect’. This difference in the behavior of PAL-e and PAL-Glide (as well as PAL-i) shows that PAL-e is an independent generalization that should not be collapsed with the other PAL constraints.

Finally, the development of //kj gj// as underlying segments is an example of phonologization in the sense of Kiparsky (2013). The observation is that secondary split is effected here not through the destruction of the environment but through the change of status of the process from across-the-board-application to derived environments.

5 Summary of interactions

This section summarizes the interaction of the constraints and compares their ranking at different levels. Before summarizing the ranking, I illustrate schematically the changes at a given level by looking at the alteration of segments in four relevant contexts: before //ε// and before //E//, across morpheme boundaries and inside morphemes. I look at velars (represented by k), coronals (represented by t) and labials (represented by p).

-

(68)

Level 1

input

k+ε

t+ε

p+ε

k+E

t+E

p+E

kε

tε

pε

kE

tE

pE

output

ʧj+ε

tj+ε

pj+ε

ʧj+E

tj+E

pj+E

kε

tε

pε

kE

tE

pE

Phonemic Velar Palatalization, k → ʧj, is executed by ranking IDENT-Dor low and *kj, *gj, *xj high, so that velars have to change into coronals. The output must be a [-anter] affricate, which is enforced by POSTER (13) and STRID (14). The details of the ranking are as follows.

-

(69)

Level 1 ranking

IDENT-C[-back] ≫ *kj *gj *xj, IDENT-V[-back], DE-PAL ≫ PAL-e, PAL-Glide ≫ IDENT-C[+back], *SOFT-Coron, *SOFT-Lab, IDENT[+anter], IDENT[-strid] ≫ POSTER, STRID, HARD, IDENT-Dor, *tɕ ≫ *ʧj

IDENT-C[-back] is undominated at level 1 because neither hardening nor loss of underlying [-back] on soft consonants is admissible. Importantly, IDENT-C[-back] ≫ *kj *gj *xj makes sure that underlying soft velars, as in kiedy //kjεdɨ// ‘when’, sail unscathed through level 1. The ranking IDENT-V[-back] ≫ IDENT-C[+back], *SOFT-Coron, *SOFT-Lab guarantees that Palatalization of hard consonants rather than Retraction of front vowels is the response to PAL constraints at level 1. PAL-e and PAL-Glide palatalize not only velars but also coronals and labials, so PAL-e, PAL-Glide ≫ *SOFT-Coron, *SOFT-Lab. Palatalization is limited to derived environments, hence DE-PAL ≫ PAL-e, PAL-Glide. Velars //k g x// palatalize to soft postalveolars /ʧj ʤj ʃj/ rather than to /kj gj xj/, so *kj *gj *xj outrank *SOFT-Coron, HARD and IDENT-Dor. Dentals //t d s z// go to /tj dj sj zj/ at level 1, so IDENT[+anter], IDENT[-strid] dominate POSTER and STRID. The outputs of PhonemicVelar Palatalization are the postalveolars /ʧj ʤj ʃj/ rather than the prepalatals /tɕ ʥ ɕ ʑ/, which means that the constraint against the latter is ranked above the constraint against the former: *tɕ ≫ *ʧj.

Level 2 segmental changes do not include palatalized labials because [pj+ε] derived at level 1 is the final output. Morpheme-internal [pε] is also the attested surface form. The inputs with yers, for instance, /pj+E/ either delete the yer (when /E/ is followed by a consonant and a full vowel) or leave the /E/ intact, so that it can vocalize at level 3: E → ε.

-

(70)

Level 2

input

ʧj+ε

tj+ε

ʧj+E

tj+E

k+εFootnote 37

kε

tε

kE

tE

output

ʧ+ε

tɕ+ε

ʧ+E

tɕ+E

kj+ε

kε

tε

kjE

tE

Level 2 witnesses Hardening, ʧj → ʧ, so HARD is reranked to an undominated position. Velars palatalize in a surface manner, k → kj, before level 2 suffixes, so in DE contexts. The yer /E/, effects k → kj in non-DE environments, so morpheme-internally. The absence of k → ʧj is accounted for by reranking IDENT-Dor to an undominated position. Finally, palatalized coronals are spelled out as prepalatals, tj → tɕ. The details are as follows.

-

(71)

Level 2 ranking

IDENT-Dor, HARD, *xj ≫ IDENT-C[-back]Footnote 38 ≫ *SOFT-Coron ≫ IDENT-V[-back]Footnote 39≫ *SOFT-Lab ≫ PAL-Glide ≫ DE-PAL ≫ PAL-e, POSTER, STRID ≫ IDENT[+anter], IDENT[-strid], IDENT-C[+back], *kj *gj, *ʧj ≫ *tɕ.

As noted, level 2 exhibits some dramatic changes. First, Phonemic Velar Palatalization is closed as an option, so IDENT-Dor is reranked to an undominated position. PAL-e and PAL-Glide palatalize velar stops in a surface manner, /k g/ → [kj gj], but the velar fricative /x/ does not palatalize at all, so *kj *gj, but not *xj, are bottom-ranked at level 2. HARD, inducing /ʧj ʤj ʃj/ → [ʧ ʤ ʃ], is obeyed without exception, so HARD is reranked to an undominated position, crucially, above IDENT-C[-back]. IDENT-C[-back] yields to HARD but not to *SOFT-Coron, *SOFT-Lab and, therefore, it continues to outrank these constraints. PAL-Glide is no longer limited to derived environments and applies morpheme-internally, as in /kEp/ → /kjEp/ ‘fool’. Consequently, PAL-Glide is reranked above DE-PAL. To induce /k g/ → [kj gj], PAL-Glide must outrank *kj *gj. PAL-e and PAL-Glide affect velars, /k g/ → [kj gj], but not coronals or labials, so *SOFT-Coron, *SOFT-Lab ≫ PAL-e, PAL-Glide. Since input soft coronals and labials do not lose their [-back] property, IDENT-C[-back] must continue outranking *SOFT-Coron, *SOFT-Lab. The enhancement spell-out operation /tj dj sj zj/ → [tɕ ʥ ɕ ʑ] is effected at level 2, hence the grip of IDENT[+anter] and IDENT[-strid] must be released by reranking POSTER and STRID above these faithfulness constraints. The spell-out produces prepalatals [tɕ ʥ ɕ ʑ] rather than postalveolars [ʧj ʤj ʃj Ʒj], so the level 1 ranking *tɕ ≫ *ʧj is reversed at level 2: *ʧj ≫ *tɕ.

Level 3 segmental changes are all allophonic and occur before the glide [j]Footnote 40 since the yer (the glide /E/) now vocalizes as a full vowel [ε], so it is no longer a glide.

-

(72)

Level 2

input

ʧ+E

tɕ+E

pj+E

kj

tj

pj

output

ʧ+ε

tɕ+ε

pj+ε

kjj

tjj

pjj

The details of the ranking are as follows.

-

(73)

Level 3 ranking

IDENT-C[-back], IDENT-Dor, IDENT[+anter], IDENT[-strid], IDENT-V[-back], PAL-Glide ≫ *SOFT-Coron, *SOFT-Lab, *kj, *gj, *xj, HARD, POSTER, STRID, *tɕ, *ʧj, DE-PAL, IDENT-C[+back] ≫ PAL-e

Level 3, the clitic level, is much like level 1, except for four facts. First, PAL-e is totally inert, so it is reranked below IDENT-C[+back]. Second, PAL-Glide is undominated and surface-true because the glide causing Palatalization surfaces overtly in the phonetic representation. Third, Palatalization is of the secondary articulation type, C → Cj, and, unlike at levels 1 and 2, does not lead to the change of place or manner of articulation. Fourth, even HARD that is exceptionless and undominated at level 2 now yields to PAL-Glide and /ʧ ʤ ʃ/ occurring before [j] end up as soft [ʧj ʤj ʃj] because [j], which is an [i] at the melodic tier, is protected by the undominated IDENT-V[-back], so the disagreement in [±back] in inputs such as /ʧ j/, as in zabacz je ‘see them’, is resolved in favor of Palatalization at the expense of violating HARD: /ʧ j/ → [ʧj j]. The segment inventory constraints prohibiting soft consonants (here: *SOFT-Coron, *SOFT-Lab, *kj *gj *xj) are bottom-ranked, so Palatalization derived by PAL-Glide prevails. DE-PAL plays no role, so it is bottom-ranked.

For the fragment of Polish phonology discussed in this article, levels 3 (clitic level) and 4 (postlexical sentence level) have the same ranking, so (73) is true for both of these levels.

The interactions summarized in this section are illustrated by a sample derivation that I take through all four levels. The example is the following fragment of a sentence: Z jej soczkiem jutro... [zj jεj sɔʧkjεmj jutrɔ] ‘with her juice (dimin.) tomorrow...’, where z ‘with’ and jej ‘her’ are proclitics, soczk+iem is the instr.sg. of socz+ek, the diminutive of sok ‘juice’, and jutro ‘tomorrow’ is an adverb. The noun [sɔʧkj+εm] contains the instr.sg. ending //εm//, which is a level 2 suffix. The level 1 input is therefore socz+ek //sɔk+Ek// ‘juice’ (dimin.). The diminutive suffix has a yer, compare the [ε] – zero alternation in socz+ek [sɔʧ+εk] (nom.sg.) – socz+k+u [sɔʧ+k+u] (gen.sg.).

The derivation of Z jej soczkiem jutro [zj jεj sɔʧkjεmj jutrɔ] ‘with her juice (dimin.) tomorrow’ proceeds as follows. The words meaning ‘juice’ and ‘tomorrow’ begin their derivation at level 1. The clitics z ‘with’ and jej ‘her’ are not available until level 3.

-

(74)

Level 1 //sɔk+Ek// → /sɔʧj+Ek/

*kj *gj *xj

DE-PAL

PAL-Glide

ID-C[+bk]

ID-Dor

*tɕ

*ʧj

a. sɔk+Ek

*!

b. sɔkj+Ek

*!

*

☞

c. sɔʧj+Ek

*

*

*

d. sɔtɕ+Ek

*

*

*!

The winner /sɔʧj+Ek/ enters level 2, at which it picks up the instr.sg. suffix –em //εm//, so the input to level 2 is /sɔʧj+Ek+εm/. Recall from Sect. 3 that level 2 has an active Yer Deletion constraint that deletes yers if they are followed by a single consonant and a full vowel, such as /ε/.Footnote 41 The /ε/ creates a context for Palatalization. The relevant constraint is PAL-e.

-

(75)

Level 2 /sɔʧj+Ek+εm/ → [sɔʧjkjεm]

Yer Del

ID-Dor

HARD

ID-C[-bk]

DE-PAL

PAL-e

ID-C[+bk]

*kj *gj

a. sɔʧj+Ek+εm

*!

*

*

b. sɔʧj+k+εm

*!

*

☞

c. sɔʧ+kj+εm

*

*

d. sɔʧ+ʧ+εm

*!

*

At level 3, /sɔʧ+kj+εm/ picks up the proclitics z ‘with’ and jej ‘her’. Only the relevant constraints are shown.

-

(76)