Abstract

Many distinct polyomaviruses infecting a variety of vertebrate hosts have recently been discovered, and their complete genome sequence could often be determined. To accommodate this fast-growing diversity, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) Polyomaviridae Study Group designed a host- and sequence-based rationale for an updated taxonomy of the family Polyomaviridae. Applying this resulted in numerous recommendations of taxonomical revisions, which were accepted by the Executive Committee of the ICTV in December 2015. New criteria for definition and creation of polyomavirus species were established that were based on the observed distance between large T antigen coding sequences. Four genera (Alpha-, Beta, Gamma- and Deltapolyomavirus) were delineated that together include 73 species. Species naming was made as systematic as possible – most species names now consist of the binomial name of the host species followed by polyomavirus and a number reflecting the order of discovery. It is hoped that this important update of the family taxonomy will serve as a stable basis for future taxonomical developments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When it was created, the family Polyomaviridae included only a handful of polyomavirus species, whose members had all been discovered by the early 1980s [21]. The situation has now changed dramatically: sequences attributed to relatives of these early polyomaviruses have been published at a much accelerated pace [5, 22], and by September 2015, more than 1200 complete polyomavirus genome sequences representing roughly 100 genetically and biologically distinct polyomaviruses had been deposited in public databases. Nearly all of them were made publicly available in the years 2000–2015, and a number of novel polyomaviruses were published while this report was being prepared.

This sudden acceleration found its roots in technological improvements that made polyomavirus discovery much easier, though still a laborious task (reviewed in [5]). Concomitantly, the first demonstration of the oncogenic potential of a polyomavirus in humans, Merkel cell PyV [6], considerably rekindled interest in this viral family. With the ever-growing body of data, new questions will emerge that will likely result in maintaining a firm foot on the discovery throttle. In this respect, it is striking to observe that even for the few well-sampled non-human mammalian hosts, e.g., chimpanzees, increasing the sample size often results in the identification of new polyomaviruses [4, 9, 13, 16, 19]. Cataloguing the diversity of this family will be a work in progress for many years. Ideally, taxonomy should accompany and help this work.

To enable taxonomic classification, pieces of information have to be identified that are frequently available and that we consider suitable to build a stable and consistent taxonomic system upon. For most novel polyomaviruses, their host and their nucleic acid sequence are the only characters within immediate reach; it is reasonable to anticipate that this will be a long-lasting status quo. Therefore, designing a host- and sequence-based taxonomy of the family Polyomaviridae seems to be the best way forward. A first step in this direction had been made by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) Polyomaviridae Study Group (SG) with the suggestion that entities with >19 % whole-genome divergence be considered members of separate species. In addition, the SG had proposed to create three genera within the family (Avi-, Wuki-, and Orthopolyomavirus) [11]. However, this approach has not been adopted by the ICTV because it did not account for the observation that some polyomaviruses are recombinants, and the phylogenetic analyses underlying the genus definition were based on different genes. In consideration of the committee’s criticisms, the SG developed novel host- and sequence-based criteria for species demarcation and genus delineation. In addition, a standardized scheme for species naming was established. These taxonomical updates were accepted by the Executive Committee of the ICTV in December 2015 and are described in this article.

Criteria for definition of polyomavirus species

Briefly, the five delineation criteria aim at ensuring that: (1) nucleic acid sequence information is public and verified and unambiguously identifies a polyomavirus (C1-C2), (2) a plausible host is known (C3), and (3) the genetic (and possibly biological) divergence qualifies the new entity as a member of a species distinct from members of all species already recognized (C4-C5). Complying with C1 to C4 is enough to justify the creation of a new species; in cases where C1 to C3 are fulfilled but C4 is not, a new species may still be validated by applying C5. The five delineation criteria are as follows:

-

C1.

The complete genome sequence is available in public databases and published in a peer-reviewed journal or an edited journal announcing the availability of genome sequences.

Note: As the binomial host species name is part of the polyomavirus species name (see below), information on the host of the virus and details regarding how the host was determined are required. Such information is usually included in publications but frequently is not available in sequence database entries.

-

C2.

The genome displays an organization typical for polyomaviruses, i.e., a dsDNA genome with an early region and a late region encoding the T antigens and the structural viral proteins on opposite strands, respectively. Both regions are separated by a noncoding control region.

Note: This criterion was set up to exclude recombinant viruses that associate polyomavirus-related coding regions with genomic elements from other viruses, e.g., bandicoot papillomatosis viruses [1, 23].

-

C3.

Sufficient information on the natural host is available.

Note: In cases where the host cannot be firmly identified by host morphology, molecular methods should be applied, e.g., mitochondrial cytochrome b typing.

-

C4.

The observed genetic distance to members of the most closely related species is >15 % for the large T antigen (LTAg) coding sequence.

Note: Under this criterion, all publicly available genomes of frequently sequenced polyomaviruses fall into their respective species (e.g., BKPyV, HPyV6, HPyV7, JCPyV, KIPyV, MCPyV, MWPyV, SV40 and WUPyV genomes). The choice of LTAg as a delineating marker was made to keep this criterion in line with the genus delineation criteria (see below). Observed genetic distances were chosen after having checked that they were very similar to patristic distances (data not shown).

-

C5.

When two polyomaviruses exhibit <15 % observed genetic distance, biological properties (e.g., host specificity, disease association, tissue tropism, etc.) can justify the creation of a new species.

-

Example 1: Two polyomaviruses are regularly detected in the same host, but C4 is not fulfilled (i.e., they exhibit less than 15 % divergence). Here, both viruses are assigned to the same species (e.g., BKPyV variants; percentage of identity: 93–100 %).

-

Example 2: Two polyomaviruses are regularly and exclusively detected in separate hosts, but C4 is not fulfilled (i.e., they exhibit less than 15 % divergence). In this case, C5 may result in assigning both viruses to separate species, i.e., C5 overrides C4. This is exemplified by the two polyomaviruses infecting squirrel monkeys of different species (percentage of identity: 89 %; Table 1).

Table 1 Polyomavirus species -

Example 3: Two polyomaviruses are regularly detected in the same host and C4 is fulfilled: the two polyomaviruses are assigned to separate species (e.g., Pan troglodytes polyomavirus 2 and 3; percentage of identity: 81 %).

-

Naming of polyomavirus species

As novel polyomaviruses are discovered at a very fast pace, the SG recommended the implementation of standardized species naming, thereby avoiding the nonsystematic inclusion of patient acronyms, geographical and biological designations, etc. into the species name. It seems clear that polyomaviruses are host-specific. Despite the use of broad-ranging and flexible detection methods, there are no (or very few) reports about any polyomavirus first discovered in an organism and later detected in another. Exceptions may be SV40 and lymphotropic polyomavirus, but the circulation of these monkey viruses in human populations – or their origin– is still a controversial issue [3, 7, 8, 15, 18]. Therefore, the SG decided to include the host species name into the polyomavirus species name. For this purpose, the binomial host species name was preferred to a common host name, as it is unique at the time of polyomavirus species creation. Naming was achieved by a combination of the Latinized host species name and the term “polyomavirus”, followed by a number. Numbers are consecutive and follow the chronological order of discovery/publication of the according polyomavirus. Example: the virus known in the literature as bovine polyomavirus (BPyV) belongs to the species Bos taurus polyomavirus 1.

Only a few exceptions to this naming scheme were accepted. The ability of budgerigar fledgling disease polyomavirus (BFDPyV) to infect multiple avian hosts [10] was accounted for by renaming the corresponding species Aves polyomavirus 1. In addition, all species accommodating human polyomaviruses were named Human polyomavirus (instead of Homo sapiens polyomavirus), followed by a number. Example: the virus known in the literature as BK polyomavirus (BKV or BKPyV) belongs to the species Human polyomavirus 1.

Definition of novel species, renaming or removal of former species

As of 2015-March-30 (cutoff date for preparation of the current taxonomical update), 68 novel polyomavirus species were defined and named, eight species were renamed and five species were removed from the Polyomaviridae, since they do not meet the novel species definition criteria. All in all, 76 species were defined, including 13 polyomavirus species with members infecting humans, 10 ape polyomavirus species (7 chimpanzee, 1 gorilla and 2 orangutan polyomavirus species), 13 monkey polyomavirus species, 21 bat polyomavirus species, 4 rodent polyomavirus species, seven species with members identified from other mammals, seven avian polyomavirus species, and one fish polyomavirus species. They are listed with their host and accession number in Table 1. Members of 61 species displayed >15 % divergence from the most closely related polyomavirus of another species. Members of 15 species displayed <15 % divergence (11-14 %) to the most closely related polyomavirus of another species but originated from different host species (Table 1).

Additional mammalian and fish polyomaviruses, including polyomaviruses of five previously ICTV-recognized species that have now been removed from the Polyomaviridae (see above) might give rise to additional species within the Polyomaviridae in the near future. They are currently excluded from species definition or have been removed from the family because their host species was not reported, their publication happened after the cutoff date, or the report was not validated by peer review (GenBank accession numbers: NC_025811, NC_007611, KM496324, NC_025800, NC_004763, AB972942, NC_026766, NC_015123, NC_020065, NC_010107, NC_010817, KJ641707, KJ641705, KJ577598, NC_025259, NC_026244, NC_026012, NC_026015, NC_026942, NC_026944, NC_027531, NC_027532).

Creation of genera and assignment of polyomavirus species to genera

The tremendous diversity of polyomaviruses naturally calls for the identification of some hierarchy within the taxonomical structure of the family, e.g., through the definition of intermediate taxa such as genera. Some years ago, the SG took a first step in this direction and proposed to delineate three genera [11]. The suggestion to create the genus Avipolyomavirus aimed at accounting for the distinctive biological properties that avian polyomaviruses display when compared to mammalian ones: broad host range and tissue tropism, no oncogenicity but marked pathogenicity, individual genomic features [11]. In line with this, phylogenetic analyses consistently supported the reciprocal monophyly of avian and mammalian polyomaviruses. Most mammalian polyomaviruses are only known from their sequences, which prevented a sound examination and comparison of their biological properties. It was, however, proposed to create two mammalian genera, respectively coined Orthopolyomavirus and Wukipolyomavirus, whose existence was essentially based on sequence divergence of the VP1-encoding gene [11]. The addition of new polyomaviruses revealed that these genera were unlikely to reflect evolutionary lineages [14] and alternative taxonomical arrangements were proposed, e.g., grouping all polyomaviruses into a single genus [20] or delineating additional genera [5]. The SG also re-examined this question, keeping in mind the important constraint that, for most novel polyomaviruses, only the host and nucleic acid sequences are known.

There is little evidence for pronounced co-divergence of polyomaviruses with their hosts in family-scale phylogenies [20], but at very deep nodes, phylogenetic trees mostly support the separation of polyomaviruses infecting birds and mammals. Although the lack of observed co-divergence may reflect a mere sampling artifact (and be corrected in the future), at the moment, there is no real possibility to use hosts as a major factor (or virus trait) to delineate genera.

The genomic organization of polyomaviruses is very uniform. Although a number of accessory open reading frames have been described, only a single one (ALTO; [2]) can be regarded as a landmark characterizing a monophyletic group of polyomaviruses. It therefore seems that genomic organization also cannot generally be used as a primary criterion for genus-level delineation.

The unique option left is to use reconstructed evolutionary relationships for the delineation of genera. Although the SG acknowledges that full-genome analyses would in principle be the ideal tool [12], the recent realization that recombination events in some instances can significantly reshuffle long-diverged genomes indicated that caution is needed [14, 20]. The SG therefore recommended using one of the three major coding sequences (LTAg, VP1 or VP2) for the delineation of genera. To the best of the SG´s knowledge, there has not been a report thus far of significant recombination events within these three coding sequences.

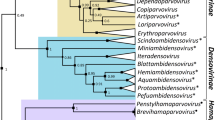

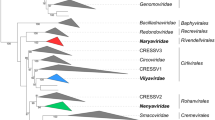

The SG proposed that evolutionary relationships derived from analyses of the LTAg amino acid sequences be used for this purpose. Our estimate of amino acid sequence variation rates based on relaxed molecular clock models obtained using BEAST v1.8.2 was lower for LTAg than for VP1 and VP2 (Fig. 1), which facilitates phylogenetic analysis. In addition, more internal branches appeared to be relatively well supported with this same fragment, as notably revealed by overlaying posterior sets of trees generated with BEAST v1.8.2 with DensiTree v2.01 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 3 shows a chronogram derived from an alignment of conserved amino acid blocks (selected with Gblocks v0.1) reconstructed with BEAST v1.8.2 under the best model of amino acid substitution (LG + F + I + G; as determined with ProtTest v3.2), a relaxed clock (lognormal) and a birth-death model of speciation. Branch thickness is proportional to posterior probability support (thin branches are less supported). A similar topology was supported by an analysis with PhyML v3 using the BEST tree search algorithm. As far as the SG is aware, it comprises sequences representative of most lineages described to date. Members of species were excluded that displayed an observed amino acid distance in LTAg of less than 5 % to a member of one of the species included in the tree, as this tree was constructed to facilitate genus delineation.

LTAg-derived Bayesian chronogram of the family Polyomaviridae. The branches supporting the existence of the four genera whose creation is recommended by the SG are indicated by a red circle. Branch support is reported above the branches (SH-aLRT/posterior probability). Detailed methods are described in Supplementary File 1. Tips display the names of species (black), the vernacular names followed by accession numbers for viruses not allocated to a polyomavirus species (grey) or, in the case of viruses other than polyomaviruses comprising an LTAg sequence, abbreviations followed by accession numbers (grey). JEECV, Japanese eel endothelial cells-infecting virus; BCPV, bandicoot papillomatosis carcinomatosis virus type 1 and 2 (BPCV1 and 2). Note: as this tree was constructed to enable genus delineation, members of species were excluded that displayed an observed amino acid distance in LTAg of less than 5 % to a member of one of the species included in the tree

Based on this, the SG recommended the creation of four genera. These include four relatively large radiations of polyomaviruses that together include 73 of the 76 species created by the SG. To name these genera, the SG decided to follow the example of other SGs that had to accommodate many species and to create numerous genera, e.g., Papillomaviridae. Genus names will therefore be composed of Greek letters followed by “polyomavirus”, e.g., Alphapolyomavirus. Greek letters will be used consecutively, following the order of description of polyomavirus genera.

In brief, members of the genera Alphapolyomavirus, Betapolyomavirus and Deltapolyomavirus are known to infect only mammals; their most recent common ancestors (MRCAs) emerged within approximately the same time frame as the MRCA of members of the genus Gammapolyomavirus. This genus (formerly named Avipoloyomavirus; [11]) includes all seven polyomavirus species whose members are known to infect birds; its type species is Aves polyomavirus 1 (Fig. 3; Table 1).

The type species of the genus Alphapolyomavirus is Mus musculus polyomavirus 1 (member: murine polyomavirus, the first polyomavirus discovered). The genus accommodates 36 species whose members infect primates (humans, apes and monkeys), bats, rodents and other mammals (Fig. 3; Table 1). The type species of the genus Betapolyomavirus is Macaca mulatta polyomavirus 1 (member: simian virus 40, the first discovered polyomavirus in this genus). Twenty-six species are included that infect primates (humans and monkeys), bats, rodents and other mammals (Fig. 3; Table 1). The type species of the genus Deltapolyomavirus is Human polyomavirus 6 (member: human polyomavirus 6, the first discovered polyomavirus in this genus). The genus is currently populated by only four human polyomavirus species (Fig. 3; Table 1).

The three polyomavirus species not assigned to any genus are Bos taurus polyomavirus 1, Centropristis striata polyomavirus 1 and Delphinus delphis polyomavirus 1. The phylogenetic placement of the polyomaviruses populating the species Bos taurus polyomavirus 1 and Delphinus delphis polyomavirus 1 came with some ambiguity, which prevented their assignment to the new genera (analyses restricted to mammalian polyomaviruses weakly support their sistership, in disagreement with Fig. 3; data not shown). The virus populating the species Centropristis striata polyomavirus 1 was, at the cutoff date, the only published PyV infecting fish. Other fish polyomavirus genomes were available in GenBank but not yet peer reviewed. The decision was made to wait for their validation before a possible incremental update of the taxonomy focused on non-tetrapod polyomaviruses.

Polyomaviruses discovered in the future: species definition and assignment to genera

The assignment of a future polyomavirus to a certain genus will rely on its unambiguous phylogenetic placement within the corresponding clade, as demonstrated by sound phylogenetic analyses of LTAg amino acid sequences. All datasets and methods used to generate the phylogenetic trees that served as the basis for the genus delineation are available as Supplementary Files 1-7. The SG suggests that authors who are willing to accompany future polyomavirus discoveries with taxonomical claims should check that their methods are mostly in line with the methods and criteria employed here.

Of note, a prerequisite for correct deduction of LTAg amino acid sequences is the proper identification of LTAg splice donor and acceptor sites. Ideally, this is done experimentally. However, as is the case for most of the currently known polyomaviruses, it can also rely on in silico analysis only. This is usually done by search for canonical splice donor and acceptor sites (http://www.umd.be/HSF3/HSF.html; [17]), followed by a selection of those that are well conserved between the virus in question and the most closely related known polyomaviruses. In addition, the observation might help that the introns of the members of genus Gammapolyomavirus are shortest (184-205 nt), followed by those of genus Betapolyomavirus (262-400 nt), genus Deltapolyomavirus (346-406 nt), and genus Alphapolyomavirus (353-565 nt). This is a rough guide predicting which length an LTAg intron should have, once preliminary BLAST and phylogenetic analysis have revealed the genus to which the novel virus may belong. Where help is needed in phylogenetic analysis of novel polyomaviruses, for publication purposes or for proposals of new species and genera to the ICTV, the SG offers to provide appropriate assistance.

Conclusions

A novel rationale for the taxonomy within the family Polyomaviridae was developed. It is mainly based on genomic sequences and host species, information that is available for most of the published polyomaviruses. The new taxonomical criteria have allowed the assignment of the vast majority of polyomaviruses to species and genera. As, after closing the polyomavirus list for preparation of the current taxonomical update (2015-March-30), additional mammalian and fish polyomavirus genomes became publicly available, new polyomavirus taxa, i.e., species and, possibly, genera, can already be seen on the horizon. They will serve as a useful touchstone for this taxonomy’s robustness.

References

Bennett MD, Woolford L, Stevens H, Van Ranst M, Oldfield T, Slaven M, O’Hara AJ, Warren KS, Nicholls PK (2008) Genomic characterization of a novel virus found in papillomatous lesions from a southern brown bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus) in Western Australia. Virology 376:173–182

Carter JJ, Daugherty MD, Qi X, Bheda-Malge A, Wipf GC, Robinson K, Roman A, Malik HS, Galloway DA (2013) Identification of an overprinting gene in Merkel cell polyomavirus provides evolutionary insight into the birth of viral genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:12744–12749

Delbue S, Tremolada S, Branchetti E, Elia F, Gualco E, Marchioni E, Maserati R, Ferrante P (2008) First identification and molecular characterization of lymphotropic polyomavirus in peripheral blood from patients with leukoencephalopathies. J Clin Microbiol 46:2461–2462

Deuzing I, Fagrouch Z, Groenewoud MJ, Niphuis H, Kondova I, Bogers W, Verschoor EJ (2010) Detection and characterization of two chimpanzee polyomavirus genotypes from different subspecies. Virol J 7:347

Feltkamp MC, Kazem S, van der Meijden E, Lauber C, Gorbalenya AE (2013) From Stockholm to Malawi: recent developments in studying human polyomaviruses. J Gen Virol 94:482–496

Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS (2008) Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science 319:1096–1100

Focosi D, Maggi F, Andreoli E, Lanini L, Ceccherini-Nelli L, Petrini M (2009) Polyomaviruses other than JCV are not detected in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Clinl Virol 45:161–162

Garcea RL, Imperiale MJ (2003) Simian virus 40 infection of humans. J Virol 77:5039–5045

Johne R, Enderlein D, Nieper H, Müller H (2005) Novel polyomavirus detected in the feces of a chimpanzee by nested broad-spectrum PCR. J Virol 79:3883–3887

Johne R, Muller H (2007) Polyomaviruses of birds: Etiologic agents of inflammatory diseases in a tumor virus family. J Virol 81:11554–11559

Johne R, Buck CB, Allander T, Atwood WJ, Garcea RL, Imperiale MJ, Major EO, Ramqvist T, Norkin LC (2011) Taxonomical developments in the family Polyomaviridae. Arch Virol 156:1627–1634

Lauber C, Gorbalenya AE (2012) Partitioning the genetic diversity of a virus family: approach and evaluation through a case study of picornaviruses. J Virol 86:3890–3904

Leendertz FH, Scuda N, Cameron KN, Kidega T, Zuberbuhler K, Leendertz SA, Couacy-Hymann E, Boesch C, Calvignac S, Ehlers B (2011) African great apes are naturally infected with polyomaviruses closely related to Merkel cell polyomavirus. J Virol 85:916–924

Lim ES, Reyes A, Antonio M, Saha D, Ikumapayi UN, Adeyemi M, Stine OC, Skelton R, Brennan DC, Mkakosya RS, Manary MJ, Gordon JI, Wang D (2013) Discovery of STL polyomavirus, a polyomavirus of ancestral recombinant origin that encodes a unique T antigen by alternative splicing. Virology 436:295–303

Lopez-Rios F, Illei PB, Rusch V, Ladanyi M (2004) Evidence against a role for SV40 infection in human mesotheliomas and high risk of false-positive PCR results owing to presence of SV40 sequences in common laboratory plasmids. Lancet 364:1157–1166

Madinda NF, Robbins MM, Boesch C, Leendertz FH, Ehlers B, Calvignac-Spencer S (2015) Genome Sequence of a Central Chimpanzee-Associated Polyomavirus Related to BK and JC Polyomaviruses, Pan troglodytes troglodytes Polyomavirus 1. Genome Announc 3

Patel AA, Steitz JA (2003) Splicing double: insights from the second spliceosome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4:960–970

Scuda N, Hofmann J, Calvignac-Spencer S, Ruprecht K, Liman P, Kuhn J, Hengel H, Ehlers B (2011) A novel human polyomavirus closely related to the african green monkey-derived lymphotropic polyomavirus. J Virol 85:4586–4590

Scuda N, Madinda NF, Akoua-Koffi C, Adjogoua EV, Wevers D, Hofmann J, Cameron KN, Leendertz SA, Couacy-Hymann E, Robbins M, Boesch C, Jarvis MA, Moens U, Mugisha L, Calvignac-Spencer S, Leendertz FH, Ehlers B (2013) Novel polyomaviruses of nonhuman primates: genetic and serological predictors for the existence of multiple unknown polyomaviruses within the human population. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003429

Tao Y, Shi M, Conrardy C, Kuzmin IV, Recuenco S, Agwanda B, Alvarez DA, Ellison JA, Gilbert AT, Moran D, Niezgoda M, Lindblade KA, Holmes EC, Breiman RF, Rupprecht CE, Tong S (2013) Discovery of diverse polyomaviruses in bats and the evolutionary history of the Polyomaviridae. J Gen Virol 94:738–748

Van Regenmortel MHV, Fauquet CM, Bishop DHL, Carstens EB, Estes MK, Lemon SM, Maniloff J, Mayo MA, McGeoch DJ, Pringle CR, Wickner RB (2000) Virus taxonomy. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego

White MK, Gordon J, Khalili K (2013) The rapidly expanding family of human polyomaviruses: recent developments in understanding their life cycle and role in human pathology. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003206

Woolford L, Rector A, Van Ranst M, Ducki A, Bennett MD, Nicholls PK, Warren KS, Swan RA, Wilcox GE, O’Hara AJ (2007) A novel virus detected in papillomas and carcinomas of the endangered western barred bandicoot (Perameles bougainville) exhibits genomic features of both the Papillomaviridae and Polyomaviridae. J Virol 81:13280–13290

Acknowledgements

This update of the Polyomaviridae taxonomy is the result of ongoing deliberations of the Polyomaviridae Study Group (currently chaired by B. Ehlers), starting in September 2012. For their valuable contributions in the earlier stages of this process, the SG is grateful to the former members of the SG, T. Allander, W. Atwood, C. B. Buck, B. Garcea, M. Imperiale, and E. O. Major. SG is indebted to A. Davison, president of the ICTV, and B. Harrach, member of the ICTV Executive Committee, for their continuous advice and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

The taxonomic changes summarized here have been submitted as an official taxonomic proposal to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) (http://www.ictvonline.org) and have now been accepted but not yet ratified. These changes therefore may differ from any new taxonomy that is ultimately approved by the ICTV.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Polyomaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses., Calvignac-Spencer, S., Feltkamp, M.C.W. et al. A taxonomy update for the family Polyomaviridae . Arch Virol 161, 1739–1750 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-016-2794-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-016-2794-y