Abstract

Research on embodied cognition stresses that bodily and motor processes constrain how we perceive others. Regarding action perception the most prominent hypothesis is that observed actions are matched to the observer’s own motor representations. Previous findings demonstrate that the motor laws that constrain one’s performance also constrain one’s perception of others’ actions. The present neuropsychological case study asked whether neurological impairments affect a person’s performance and action perception in the same way. The results showed that patient DS, who suffers from a frontal brain lesion, not only ignored target size when performing movements but also when asked to judge whether others can perform the same movements. In other words DS showed the same violation of Fitts’s law when performing and observing actions. These results further support the assumption of close perception action links and the assumption that these links recruit predictive mechanisms residing in the motor system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The assumption that the motor system supports cognition has gained a lot of popularity in the last decade. It implies that basic bodily and motor processes constrain not only what individuals can perceive, feel, and do, but also how they understand and relate to others (Sommerville & Decety, 2006). One way to conceptualize motor contributions to perception and cognition is the assumption of common coding (Prinz, 1997; Prinz & Hommel, 2002) that is inspired by James (1890) ideomotor principle for voluntary action. This principle states that imagining an action creates a tendency to carry it out. Common coding theory extends the ideomotor principle and claims that the same mental representations are involved in performing actions and observing actions. These representations code the “perceivable” effect of actions. During performance common codes are activated from the inside and then further specified in the motor system. During observation they are activated from the outside and lead to “motor resonance”.

A large body of neurophysiological evidence supports the assumption of a common coding for perception and action (Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004). Mirror neurons found in the premotor cortex of the monkey brain and the analogous mirror system in humans are engaged in perception as well as in execution of action supporting the view that others’ actions are coded in a functionally equivalent way as one’s own actions. The primary function of the common representations implemented in the mirror system has so far been attributed to action understanding (Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004), that is, extracting the goals that underlie observed actions (Wohlschlaeger & Bekkering, 2002; Hamilton & Grafton, 2006; Rizzolatti, Fogassi, & Gallese, 2001).

However, there is also reason to believe that mirror matching contributes to predicting others’ actions in real time (Knoblich & Flach, 2001; Knoblich, Seigerschmidt, Flach, & Prinz, 2002; Wilson & Knoblich, 2005). Accordingly, simulation theories (Jeannerod, 2001; Wilson & Knoblich, 2005; Schubotz, 2007) propose that people use internal models (Wolpert, Ghahramani, & Jordan 1995; Frith, Blakemore & Wolpert, 2000) to predict the future sensory and perceptual consequences of observed actions. The idea is that the same models that are used to plan one’s own actions can be exploited in action perception.

In the context of action planning, internal models reflect previously experienced relationships between actions and their outcomes (Kawato, 1999; Miall, 2003; Wolpert et al., 1995). With every motor command generated during movement execution, the motor system produces an efference copy of that motor command in parallel. Based on this copy, the forward model estimates the sensory consequences of the movement. The estimate stands in for the re-afferent information coming from sensory channels and is used in further processing until the actual re-afferent information arrives at the central nervous system (e.g., Frith et al., 2000). The critical assumption in the simulation accounts above is that forward models are instrumental in action perception. Accordingly, an observed action is matched with our own repertoire and is simulated via the internal models using the same efference copy. In other words, perception and action matching allows us to exploit already existing predictive mechanisms in the motor system to make sense of others’ actions.

In summary, “motor theories” of action perception suggest that perceived actions are matched to one’s own action repertoire and that this matching activates internal models that allow one to predict the outcome of perceived actions. One testable implication of these assumptions is that the principles or “laws” that constrain production of movement should affect action perception. The reason is that motor simulations should impose the constraints of one’s own motor apparatus onto observed actors. Before describing a neuropsychological case study on patient DS that further tested this claim we shortly summarize earlier evidence that has been obtained with regard to two well-established motor laws: The two-thirds power law (Lacquaniti, Terzuolo, & Viviani, 1983) and Fitts’s law (Fitts, 1954). In particular, we will focus on results suggesting that these motor laws affect how we perceive others.

Two-thirds power law

The two-thirds power law (Lacquaniti et al., 1983; Viviani, 2002) describes the relationship between the velocity of a movement and the curvature of its trajectory. The law states that as curvature increases one needs to systematically slow down. As the curvature decreases, on the other hand, one can systematically accelerate the movement. This change in velocity is directly proportional to the change in curvature. The two-thirds power law has been shown to hold for most types of human movement, including manual (Viviani & Mounoud, 1990) or eye tracking movements (de Sperati & Viviani, 1997). Studies that investigated perceptual judgments for movements indicate that the two-thirds power law constrains perception of action in the same way as it constrains production. For example, it was shown that people’s perception of geometric and kinematic properties of end-point trajectories, such as drawing and writing (Viviani & Stucchi, 1989, 1992), is systematically biased towards complying with the two-thirds power law (Lacquaniti et al., 1983).

Further support comes from a recent functional MRI study (Dayan et al., 2007) which investigated the neural correlates of the two-thirds power law by presenting participants visual stimuli that were either in compliance with or in violation of this law. The authors found that the stimuli obeying the two-thirds power law yielded stronger and more widespread activation in areas associated with action production, action perception and visual motion processing.

Kandel, Orliaguet and Boe (2000) investigated whether the two-thirds power law also influences an observer’s ability to predict the future course of handwriting trajectories. They found that the predictions were most accurate for trajectories that complied with the law and became less accurate as trajectories were manipulated to deviate from it. Flach, Knoblich and Prinz (2004) reported similar findings for a representational momentum paradigm (Hubbard, 2005), where subjects are typically asked to predict the future course of a movement. Errors in prediction were smaller when the observed movement trajectories complied with the two-thirds power law.

The results described above suggest that anticipating the future course of a perceived movement is easier when it corresponds to the constraints that govern the actions that produce this movement. They can be interpreted as support for the claim that we perceive and understand movements through the lens of our motor repertoires. When perceived events are predictable by an internal model in the motor system people can better anticipate what will follow than when the perceived events are not predictable by an internal model.

Fitts’s law

Fitts’s law (Fitts, 1954) is perhaps the most stable law in human motor control (for a review, see Plamondon & Alimi, 1997), and has been studied extensively by the human computer interaction (HCI) field as well as psychophysics. The law captures the speed accuracy trade-off observed in human movement, and states that the average time it takes to move between two targets is determined by the width of the targets and the distance separating them. With increasing target width, one can move faster between the targets without missing them. With increasing distance between targets, one takes longer to move between them. Fitts’s law expresses this trade-off between speed and accuracy as:

where MT is movement time, ID is the index of difficulty, and a and b are empirical constants. The critical variable is the ID, which relates the amplitude (A) of the movement to the width (W) of the targets. It is expressed as:

The main quantitative prediction that can be derived from Fitts’s law is that different combinations of target width and movement amplitude can yield the same index of difficulty, and thus the same MT (see Table 1 for examples). Fitts’s law holds for many forms of movement production including different effectors and movement contexts, with only a few exceptions (e.g., Chi & Lin, 1997; Danion, Duarte, & Grosjean, et al., 1999).

Decety and Jeannerod (1996) were the first to demonstrate that Fitts’s law not only holds for movements that are actually performed but also for movements one imagines to perform. They asked participants to imagine walking in a three-dimensional virtual environment towards gates of varying widths situated at varying distances and found that the mental MT it took the participants to move between the two gates was a linear function of the index of difficulty (ID), just as predicted by Fitts’s law. The imagined MT increased with increasing apparent distance between the gates, and with decreasing gate width. This result shows that imagined actions maintain the temporal characteristics of the same actions executed (Decety, Jeannerod, & Prablanc, 1989; Sirigu et al., 1995, 1996), indicating that the same internal models are at work when performing and imagining actions.

There is also evidence that a person has implicit knowledge of Fitts’s law when preparing for future movements, when perceiving the constraints of planned movements, and when evaluating the difficulty of planned movements (Augustyn & Rosenbaum, 2005; Sirigu et al., 1995, 1996; Maruff & Velakoulis, 2000; Slifkin & Grilli, 2006). Other motor imagery studies using a variety of tasks, such as walking (Bakker, de Lange, Stevens, Toni, & Bloem, 2007; Decety et al., 1989), simple hand actions (Sirigu et al., 1996; Choudhury, Charman, Bird, & Blakemore, 2007), drawing (Decety & Michel, 1989) or reaching targets (Maruff & Velakoulis, 2000) confirm that the same motor representations govern an action whether it is real or imagined. Index of difficulty affects actions in the same way irrespective of their modalities. Taken together, similarity in temporal properties between real and imagined movements (Decety & Jeannerod, 1996; Decety & Michel, 1989) suggests that overlapping motor mechanisms are recruited for both types of movement.

Results from another recent study suggest that observation of action may recruit similar motor processes as performing and imagining movements. In particular, Grosjean, Shiffrar and Knoblich (2007) have shown that Fitts’s law holds when people are asked to judge how fast another person can move. In this experiment, participants were shown alternating pictures of a person moving their arm between two targets. Index of difficulty (ID) was varied choosing appropriate movement amplitudes and target widths. Nine different amplitude/width combinations were used, yielding three conditions for each of three IDs. The participants were asked to report whether the person could perform such a movement without missing the targets. Alternating pictures were chosen instead of video clips to avoid any additional information provided by movement trajectories. The perceived MTs were defined in terms of the speed at which the participants reported an equal number of ‘possible’ and ‘impossible’ judgments.

The perceived MTs were found to vary linearly as a function of ID (r 2 = 0.96), indicating that the MTs did not vary as a function of target width or movement amplitude alone. These results demonstrated that the same motor law constraining action production and motor imagery constrains action perception as well. Providing a solid support for motor contributions to action perception, this study reinforced the relationship between action production, motor imagery and action perception, in line with evidence for overlapping neural systems for these three motor domains (Grezes & Decety, 2001; Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004).

The authors explain these results with the following model (see Fig. 1) postulating that simulations are run via two separate routes. One route deals with the contextual information surrounding an action (task layout) and one deals with the kinematics (spatiotemporal characteristics) of the observed action. A representation of the task layout constrains internal models towards simulating the action so that it could be executed in that given environment (cf. Pacherie, 2008). In other words, predicted speed (or MT) for the movement depends on the context within which the action is embedded and the biomechanical constraints reflected in the internal models. In order to decide whether an observed movement is doable or not, the speed prediction is contrasted with the perceived movement speed.

Proposed dual route model of action perception. Contextual information and the kinematics of the observed actions are coded independently via separate routes of internal simulations, The two routes feed into and are reconciled by the predictors that yield a judgment with respect to the doability of the perceived action

The dynamic model of Erlhagen, Mukovskiy, & Bicho (2006) suggests possible neural correlates of these separate routes. In this model, simulation and action understanding are integrated within a continuous dynamic process. Accordingly, contextual information, movement information, and the goal of the movement are represented as dynamic activity in layered neural networks. One part of the model consists of the premotor-parietal-STS (superior temporal sulcus) mirror circuitry responsible for action observation and action execution. This circuitry is inter-connected with a layer in prefrontal cortex (PFC) that is proposed to encode the intentional action goal framed by the context in which the action is set.

If the contextual constraints in which actions are embedded are processed by prefrontal areas, as claimed by Erlhagen et al. (2006), then we would expect a lesion in this area to misrepresent the context of an action, and hence the reasons driving it. Particularly in a Fitts’s task, a patient with a prefrontal lesion would not be able to integrate the task layout into his representation of the observed movement. This, in turn, would not only impair his ability to adapt his movement speed but in the same manner his ability to judge whether an observed person can achieve a certain movement speed or not. In the following, we report a study that tested this hypothesis in the neuropsychological patient DS whose lesion encompasses the left frontal lobe.

Patient DS

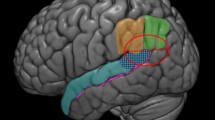

DS is a 74-year-old former train inspector who suffered a stroke in 1995. He is able to function at a relatively self-sufficient manner despite his hemiplegia of the right side. Following his accident, a wide range of neuropsychological measures and an MRI-scan of his lesion were obtained. His MRI-scan revealed damage to the left inferior, middle and superior frontal gyri (see Fig. 2). DS’s scores on low level visual perception and object naming were relatively normal. He scored 100% on unusual views matching, and 86% on naming everyday objects. Despite a few semantic errors in naming, DS used these objects appropriately.

Method

Participants

In addition to patient DS, five healthy control participants were tested in exchange for course credit or money. The control participants reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision. They were not age-matched as Fitts’s law has been shown to hold across different age groups (Skoura, Papaxanthis, Vinter, & Pozzo, 2005).

Materials

Material and apparatus

Stimulus presentation and response registration were managed by an IBM compatible computer using E-Prime software version 1.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.). The stimuli used were pairs of digital photographs of an arm pointing at one of the two targets placed on a flat surface (see Fig. 3). The two targets were of identical widths and were separated by varying amplitudes. Across trials, each of three widths (2, 4 and 8 cm) was combined with three of five amplitudes (4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 cm) to make up for three IDs (2, 3 and 4; see Table 1). The pair of photographs was repeatedly alternated to create apparent motion.

Procedure and design

The rate at which the stimuli were alternated was set at 1 of 11 stimulus-onset asynchronies (SOAs), which also corresponded to the durations of individual frames. SOAs ranged from 150 to 650 ms in increments of 50 ms. Each trial started at an SOA of either 150 or 650 ms. The SOAs could be changed with key presses. Key [1] shortened the SOA by one step, key [2] lengthened the SOA by one step, and key [3] was programmed to go on to the next trial. The task was to choose the speed at which the movement between the two targets was just doable. The participants could modify the SOAs as often as they wanted until they were satisfied, before they moved on to the next trial. The SOA that was ultimately chosen on a given trial was defined as the MT that was perceived as just doable. A 3 (width) × 3 (ID) × 2 (hand) factorial design was used. Half of the stimuli showed right-hand movements and half showed left-hand movements. Each block of 72 trials was presented to the participants in a random order, following a short practice session. The running time for each block was roughly 20 min, and three blocks were completed.

The patient was also asked to execute the same actions presented in the action perception task. Targets of same widths as in the previous task were placed across each other at varying amplitudes, to create the same IDs (see Table 1). DS was instructed to move between the targets as fast and as accurately as possible while a video camera recorded his performance. Produced MT for a given trial was defined as the average duration of a single movement between the targets, i.e., 10 s divided by the total number of performed movements.

The patient could perform the task with his left hand only, due to his hemiplegia. Each of the nine trial types was tested twice. Trials were presented in a random order within the same block. No control participants were tested for this task, as Fitts’s law is well established in action production across age groups (Skoura et al., 2005).

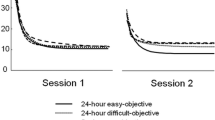

Results

Figure 4 presents the mean perceived MTs as a function of width and index of difficulty (ID), for patient DS and the five control participants. The results for the controls are consistent with Fitts’s law and our previous findings (Grosjean et al., 2007). Perceived MTs increased linearly with ID (see bottom panel of Fig. 4). The regression analysis yielded a significant r 2 of 0.91 [F(1, 7) = 74.13, P < 0.001] and the following regression equation for MT: MT = 269 + 48ID. In contrast, the data for patient DS did not obey Fitts’s law (see top panel of Fig. 4). ID only accounted for a small and nonsignificant portion of the variance in DS’s perceptual judgments [r 2 = 0.34, F(1, 7) = 3.61, P = 0.099]. The resulting regression equation was MT = 219 + 51ID.

Figure 5 displays the same data plotted as a function of movement amplitude (A), that is, distance between the targets instead of ID. As can be seen in the top panel of the figure, movement amplitude was an almost perfect predictor for which MTs DS perceived as just doable, as evidenced by the r 2 of 0.98 [F(1, 7) = 451.93, P < 0.001. The resulting regression equation was MT = 284 + 4]. As would be expected, based on the results presented above, movement amplitude was a weaker predictor for the control participants’ performance (see bottom panel of Fig. 5) because it fails to take into account the influence of W [r 2 = 0.66, F(1, 7) = 13.83, P < 0.01. The resulting regression equation was MT = 371 + 2A].

The action production data gathered from DS are depicted in Fig. 6. As was already observed for his perceptual data, movement amplitude [r 2 = 0.93, F(1, 7) = 93.44, P < 0.001, regression equation MT = 257 + 3A; see bottom panel of Fig. 6] proved to be a much better predictor of his performance than ID [r 2 = 0.65, F(1, 7) = 13.03, P < 0.01, regression equation MT = 176 + 46ID; see top panel of Fig. 6]. Thus, both his perceptual and production data violated Fitts’s law in similar ways: MT was linearly related to movement amplitude rather than index of difficulty. Finally, in line with what would be expected if DS relied on a similar set of representations and/or processes in both tasks, we found that his perceived and produced MTs were almost perfectly correlated across conditions [r 2 = 0.88, F(1, 7) = 50.34, P < 0.001].

Discussion

The results clearly indicate that patient DS relies solely on movement amplitude (the distance between two targets) when judging whether a movement was doable or not, and disregarded the target width. This suggests that DS seems to have lost the ability to integrate contextual constraints in action simulations, resulting in a deficiency in predicting an appropriate action speed for that given environment. Consequently, the resulting speed prediction was solely based on the amplitude of the movement. At the same time, the performance data indicated exactly the same deficit when he was asked to move as quickly possible between the two targets. This suggests that DS’s lesion affects his performance and his perception of others’ movements in the same way.

Although the control participants used in our study were not age-matched, it is unlikely that DS’s results can be attributed to general motor deterioration due to aging. First, Skoura et al. (2005) demonstrated that Fitts’s law holds for motor production in the elderly. Potentially troubling is their finding that elderly participants disregarded varying target widths during the motor imagery task (but not the motor production task). This finding seems to converge with the present result that patient DS disregarded width. It has to be kept in mind, however, that index of difficulty accounts for a much lesser amount of variance in DS’s doability judgments for perceived movements, than it accounted for in the motor imagery condition (r 2 = 0.34 and 0.89, respectively) in Skoura et al.’s study on elderly participants. These numbers seem to rule out the possibility that patient DS’s selective impairment is merely a by-product of aging.

It should also be noted that Skoura et al., attribute the violation of Fitts’s law in imagined movements to the aging parietal cortex. Sirigu et al. (1996) similarly found that patients with parietal lesions violated Fitts’s law in the same domain (motor imagery). The possibility has to be acknowledged that patient DS’s diffuse lesion in the frontal lobe might encompass this area’s links with the adjacent parietal lobe and result in his selective disregard to the target widths. Importantly, however, both mentioned studies found that parietal impairment did not yield to violation of Fitts’s law in action production, but only in motor imagery. In contrast, patient DS violated Fitts’s law in both of the tested action domains. Therefore, his parallel impairment in action production and action perception cannot be attributed to a potential injury in his parietal cortex.

The dynamic model outlined by Erlhagen et al. (2006) provides a plausible explanation to patient DS’s data. In this model the mirror circuitry (i.e. superior temporal sulcus, inferior parietal lobule and the inferior frontal gyrus) performs the matching of observed actions with the existing motor repertoire. The PFC, on the other hand, acts as the ‘goal layer’ (ibid. p. 177) and encodes the goal of the observed action, which is constrained by the action context. In DS’s case, the PFC cannot perform this function and the matching process between perception and action proceeds orthogonally to the action context.

Conclusions

The results of the present study clearly indicate that DS’ data are best understood as reflecting a specific deficit that is caused by a brain lesion that affect action production and action perception in exactly the same way. When presented with a Fitts’s like task, DS’s ‘doability’ judgments for observed movements were found to be a direct function of the distance between targets. Remarkably, DS’s produced movements slowed down as this distance increased, indicating that in both cases patient DS exhibited a specific disability to integrate target size into his motor representation.

As stipulated by Fitts’s law, previous research in healthy adults has demonstrated that difficulty of a movement (reflected in MT) is a function of the target width and the distance between the target pair. In line with the dynamic model proposed by Erlhagen, we attribute this specific deficit in DS to his lesion of the prefrontal lobe that precludes influences of the task layout on motor simulation. Although DS still perceives others’ action capabilities through the lens of his own motor repertoire, the brain systems encoding task context are dysfunctional and can therefore not inform the simulations. This is not to say that all influences on motor simulations are top-down. Previous research has shown that the lack of peripheral (bottom-up) input to the body schema can also lead to difficulties in action observation and action understanding (Bosbach, Cole, Prinz, & Knoblich, 2005; Bosbach, Knoblich, Reed, Cole, & Prinz, 2006).

Patient DS is yet another illustration of how mechanisms governing action performance constrain what is perceived to be ‘doable’ in others. In functional terms this suggests a common coding of perception and action that allows perceived actions to be matched to one’s own action capabilities (Prinz, 1997). Once common codes are activated the motor system runs simulations to predict the likely future of the ongoing actions that are being observed, thereby directly serving perception. The use of such simulations, which are evidently contingent upon the observer’s motor repertoire, renders perception a function of motor processes.

Simulations in general can be defined as partial recreations of previously experienced perceptual as well as motor states (Barsalou, 2008). They serve as the means through which we anticipate the world around us thereby allowing for further mental processing. This emphasizes the neglected flipside of the bidirectional link between bodily and mental states and offers us a plausible explanation as to how our interactions with the world ground cognition.

References

Augustyn, J. S., & Rosenbaum, D. A. (2005). Metacognitive control of action: Preparation for aiming reflects knowledge of Fitts’s law. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(5), 911–916.

Bakker, M., de Lange, F. P., Stevens, J. A., Toni, I., & Bloem, B. R. (2007). Motor imagery of gait: A quantitative approach. Experimental Brain Research, 179(3), 497–504.

Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 59, 617–645.

Bosbach, S., Cole, J., Prinz, W., & Knoblich, G. (2005). Understanding another’s expectation from action: The role of peripheral sensation. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 1295–1297.

Bosbach, S., Knoblich, G., Reed, C., Cole, J., & Prinz, W. (2006). Body inversion effect without body sense: Insights from deafferentation. Neuropsychologia, 44, 2950–2958.

Chi, C. F., & Lin, C. L. (1997). Aiming accuracy of the line of gaze and redesign of the gaze-pointing system. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 85(3), 1111–1120.

Choudhury, S., Charman, T., Bird, V., & Blakemore, S.-J. (2007). Development of action representation during adolescence. Neuropsychologia, 45(2), 255–262.

Danion, F., Duarte, M., & Grosjean, M. (1999). Fitts’ law in human standing: The effect of scaling. Neuroscience Letters, 277, 131–133.

Dayan, E., Casile, A., Levit-Binnun, N., Giese, M., Hendler, T., & Flash, T. (2007). Neural representations of kinematic laws of motion: Evidence of action-perception coupling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(51), 20582–20587.

de Sperati, C., & Viviani, P. (1997). The relationship between curvature and velocity in two-dimensional smooth pursuit eye movements. The Journal of Neuroscience, 17(10), 3932–3945.

Decety, J., & Jeannerod, M. (1996). Mentally simulated movements in virtual reality: Does Fitts’s law hold in motor imagery? Behavioral Brain Research, 72, 127–134.

Decety, J., Jeannerod, M., & Prablanc, C. (1989). The timing of mentally represented actions. Behavioral Brain Research, 34(1–2), 35–42.

Decety, J., & Michel, F. (1989). Comparative analysis of actual and mental movement times in 2 graphic tasks. Brain and Cognition, 11(1), 87–97.

Erlhagen, W., Mukovskiy, A., & Bicho, E. (2006). A dynamic model for action understanding and goal-directed imitation. Brain Research, 1083, 174–188.

Fitts, P. M. (1954). The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 47(6), 381–391.

Flach, R., Knoblich, G., & Prinz, W. (2004). Recognizing one’s own clapping: The role of temporal cues. Psychological Research, 69(1–2), 147–156.

Frith, C. D., Blakemore, S. J., & Wolpert, D. M. (2000). Abnormalities in the awareness and control of action. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 355(1404), 1771–1788.

Grezes, J., & Decety, J. (2001). Functional anatomy of execution, mental simulation, observation, and verb generation of actions: A meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping, 12(1), 1–19.

Grosjean, M., Shiffrar, M., & Knoblich, G. (2007). Fitts’s law holds for action perception. Psychological Science, 18(2), 95–99.

Hamilton, A. F. D., & Grafton, S. T. (2006). Goal representation in human anterior intraparietal sulcus. The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(4), 1133–1137.

Hubbard, T. L. (2005). Representational momentum and related displacements in spatial memory: A review of the findings. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(5), 822–851.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology (2 vols.). New York: Holt.

Jeannerod, M. (2001). Neural simulation of action: A unifying mechanism for motor cognition. NeuroImage, 14, 103–109.

Kandel, S., Orliaguet, J. P., & Boe, L. J. (2000). Detecting anticipatory events in handwriting movements. Perception, 29(8), 953–964.

Kawato, M. (1999). Internal models for motor control and trajectory planning. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 9(6), 718–727.

Knoblich, G., & Flach, R. (2001). Predicting the effects of actions: Interactions of perception and action. Psychological Science, 12, 467–472.

Knoblich, G., Seigerschmidt, E., Flach, R., & Prinz, W. (2002). Authorship effects in the prediction of handwriting strokes. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 55A, 1027–1046.

Lacquaniti, F., Terzuolo, C., & Viviani, P. (1983). The law relating the kinematic and figural aspects of drawing movements. Acta Psychologica, 54(1–3), 115–130.

Maruff, P., & Velakoulis, D. (2000). The voluntary control of motor imagery. Imagined movements in individuals with feigned motor impairment and conversion disorder. Neuropsychologia, 38(9), 1251–1260.

Miall, R. C. (2003). Connecting mirror neurons and forward models. NeuroReport, 14(17), 2135–2137.

Pacherie, E. (2008). The phenomenology of action: A conceptual framework. Cognition, 107(1), 179–217.

Plamondon, R., & Alimi, A. M. (1997). Speed/accuracy trade-offs in target-directed movements. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 20(2), 279–349.

Prinz, W. (1997). Perception and action planning. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 9, 129–154.

Prinz, W., & Hommel, B. (2002). Common mechanisms in perception and action—Introductory remarks. In W. Prinz, & B. Hommel (Eds.), Common mechanisms in perception and action: Attention & performance XIX (pp. 3–5). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rizzolatti, G., & Craighero, L. (2004). The mirror-neuron system. Annual Review Neuroscience, 27, 169–192.

Rizzolatti, G., Fogassi, L., & Gallese, V. (2001). Neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the understanding and imitation of action. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2(9), 661–670.

Schubotz, R. I. (2007). Prediction of external events with our motor system: Towards a new framework. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(5), 211–218.

Sirigu, A., Cohen, L., Duhamel, J. R., Pillon, B., Dubois, B., Agid, Y., et al. (1995). Congruent unilateral impairments for real and imagined hand movements. NeuroReport, 6(7), 997–1001.

Sirigu, A., Duhamel, J. R., Cohen, L., Pillon, B., Dubois, B., & Agid, Y. (1996). The mental representation of hand movements after parietal cortex damage. Science, 273(5281), 1564–1568.

Skoura, X., Papaxanthis, C., Vinter, A., & Pozzo, T. (2005). Mentally represented motor actions in normal aging I. Age effects on the temporal features of overt and covert execution of actions. Behavioural Brain Research, 165(2), 229–239.

Slifkin, A. B., & Grilli, S. M. (2006). Aiming for the future: Prospective action difficulty, prescribed difficulty, and Fitts’ law. Experimental Brain Research, 174(4), 746–753.

Sommerville, J. A., & Decety, J. (2006). Weaving the fabric of social interaction: Articulating developmental psychology and cognitive neuroscience in the domain of motor cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13(2), 179–200.

Viviani, P. (2002). Motor competence in the perception of dynamic events: A tutorial. In W. Prinz, & B. Hommel (Eds.), Common mechanisms in perception and action: Attention and performance XIX (pp. 406–442). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Viviani, P., & Mounoud, P. (1990). Perceptuomotor compatibility in pursuit tracking of 2 dimensional movements. Journal of Motor Behavior, 22(3), 407–443.

Viviani, P., & Stucchi, N. (1989). The effect of movement velocity on form perception—Geometric illusions in dynamic displays. Perception & Psychophysics, 46(3), 266–274.

Viviani, P., & Stucchi, N. (1992). Biological movements look uniform—Evidence of motor perceptual interactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and Performance, 18(3), 603–623.

Wilson, M., & Knoblich, G. (2005). The case for motor involvement in perceiving conspecifics. Psychological Bulletin, 131(3), 460–473.

Wohlschlaeger, A., & Bekkering, H. (2002). Is human imitation based on a mirror-neuron system? Some behavioural evidence. Experimental Brain Research, 143(3), 335–341.

Wolpert, D. M., Ghahramani, Z., & Jordan, M. I. (1995). An internal model for sensorimotor integration. Science, 269(5232), 1880–1882.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Eskenazi, T., Grosjean, M., Humphreys, G.W. et al. The role of motor simulation in action perception: a neuropsychological case study. Psychological Research 73, 477–485 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-009-0231-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-009-0231-5