Abstract

The proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) has emerged as a promising treatment target to lower serum cholesterol, a major risk factor of cardiovascular diseases. Gain-of-function mutations of PCSK9 are associated with hypercholesterolemia and increased risk of cardiovascular events. Conversely, loss-of-function mutations cause low-plasma LDL-C levels and a reduction of cardiovascular risk without known unwanted effects on individual health. Experimental studies have revealed that PCSK9 reduces the hepatic uptake of LDL-C by increasing the endosomal and lysosomal degradation of LDL receptors (LDLR). A number of clinical studies have demonstrated that inhibition of PCSK9 alone and in addition to statins potently reduces serum LDL-C concentrations. This review summarizes the current data on the regulation of PCSK9, its molecular function in lipid homeostasis and the emerging evidence on the extra-hepatic effects of PCSK9.

Similar content being viewed by others

Protein convertase–LDL receptor interaction

The main function of the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin (PCSK) type 9 (PCSK9) is the proteolytic maturation of secreted proteins such as hormones, cytokines, growth factors, and cell surface receptors [149]. The name PCSK9 stems from the relation to bacterial subtilisin and yeast kexin and the presence of nine secretory serine proteases. PCSK9 is expressed mainly in the liver, the intestine, the kidney, and the central nervous system [122].

PCSK9 is a 692 amino acid protein with a molecular weight of 72 kDa that consists of a prodomain (PD), a catalytic domain and a cysteine- and histidine-rich C-terminal domain (CHRD) [41] (Fig. 1). The best characterized function of PCSK9 relates to the binding to LDL-C receptors (LDLR) in hepatocytes. Pro-PCSK9 (72 kDa) is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) as is the precursor form (120 kDa) of the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor (LDLR). The binding of pro-PCSK9 to the LDLR in the ER supports the transport of the LDLR from the ER [163] towards the Golgi complex, where the LDLR acquires its mature carbohydrate residues (160 kDa). Trafficking of pro-PCSK9 to the Golgi apparatus depends on the presence of the protein Sec24A [31]. Within the Golgi, the pro-domain of pro-PCSK9 is auto-catalytically cleaved off, but remains non-covalently bound to the mature PCSK9 assisting the folding of PCSK9, and blocking its catalytic activity [61]. Binding of pro-PCSK9 to the precursor form of the LDLR promotes PCSK9 auto-catalytic cleavage [163].

The structure of PCSK9 contains a signal peptide (SP, amino acids 1–30), a prodomain (Pro, amino acids 31–152), a catalytic domain and the C-terminal domain. The cleavage of the prodomain is required for PCSK9 folding and maturation. The location of the aspartic acid (D), histidine (H) and serine (S) comprising the catalytic triad and the site of binding of the single N-linked sugar (Asn533) are shown. The oxyanion hole is located at Asn317. Mutations associated with elevated plasma levels of LDL-C are depicted at the top (blue), mutations leading to reduced LDL-C at the bottom (green). The asterisk indicates mutations associated with elevated plasma LDL-C levels found only in families who also have mutations in the LDL receptor (modified from [75])

Some of the loss-of-function (LOF) mutations of PCSK9—as the exchange of amino acids C678X [15] or S462P [25]—abolish the release of PCSK9 from the ER as does loss of parts of its PD [49]. On its way through the Golgi and trans-Golgi complex, PCSK9 co-localizes with the protein sortilin; in sortilin-knockout mice the plasma PCSK9 concentration is decreased suggesting that such protein–protein interaction is required for cellular secretion of PCSK9 [66]. In healthy humans, circulating PCSK9 levels directly correlate with plasma sortilin levels [66]. The exchange of amino acids S127R and D124G reduces secretion of PCSK9 from hepatocytes and increases the intracellular expression of PCSK9 [72]. It appears that partial proteolysis of PCSK9 is required prior to its cellular secretion [36]. Proteolysis of PCSK9 is regulated by phosphorylation at its residues serine 47 (PD) and serine 688 (CHRD) which occurs by a Golgi casein kinase-like kinase; an increase in epitope phosphorylation reduces proteolysis of PCSK9 [45].

Apart from acting as a chaperone to transport the precursor form of the LDLR from the ER, intracellular PCSK9 plays a role in regulating the expression of the mature LDLR by inducing intracellular degradation of the LDLR prior to its transport to the cell surface membrane. Given the fact that the mature LDLR and PCSK9 are found in the Golgi complex, it is likely that the LDLR degrading effect of PCSK9 occurs in or is initiated in the Golgi or trans-Golgi complex [107, 108]. The post-ER mechanism of LDLR degradation requires the catalytic activity of PCSK9 [13, 14].

If not degraded intracellularly, the mature LDLR is transported to the cell surface, where it resides in clathrin-coated pits because of its interaction with the low-density lipoprotein receptor adapter protein 1, which may cause autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia (ARH). The LDLR undergoes endocytosis in the presence or absence of its ligand, entering the endocytic recycling compartment. The change in pH within this compartment allows dissociation of the LDLR from its ligand, which then becomes degraded in the lysosome while the LDLR recycles.

The main role of secreted extracellular PCSK9 is to post-translationally regulate the number of cell surface LDLR. Secreted PCSK9 binds to the epidermal growth factor repeat A (EGF-A) region of the LDLR [21, 32, 179]. For such binding, the catalytic activity of PCSK9 is not required [101, 115], but pH changes and changes in the positive [70] or negative [71] charges of PCSK9 epitopes affect its binding affinity to the LDLR [16, 62]. Mutations in the EGF-A binding domain of the LDLR associated with familiar hypercholesterolemia increases PCSK9 binding [114]. The formed PCSK9–LDLR complex is internalized again by clathrin-mediated endocytosis [124, 130] and the complex is then routed to the sorting endosome/lysosome via a mechanism that does not require ubiquitination [172], but might involve interaction of the cytosolic tail of PCSK9 with the amyloid precursor protein like protein 2 [44]. At the acidic pH of the endosome/lysosome, an additional interaction between the ligand-binding domain of the LDLR and the C-terminal domain of PCSK9 occurs [49, 142]; as a consequence PCSK9 remains bound to the LDLR and the LDLR fails to adopt a closed conformation which is required for LDLR recycling. The failure of the LDLR to recycle appears to also involve ectodomain cleavage by a cysteine cathepsin in the sorting endosome [97]. Thus, by binding to the LDLR, PCSK9 disrupts the recycling of the LDLR leading to its degradation and subsequently a reduced number of available LDLRs. LDLR lacking its cytoplasmic domain are also degraded by PCSK9 [162] (Fig. 2).

PCSK9 undergoes self-assembly and forms PCSK9 dimers or trimers which have greater LDLR degrading activity [53]. One of the gain-of-function (GOF) mutations of PCSK9 (D374Y) is characterized by an enhanced PCSK9 self-assembly [53]. The main route of PCSK9 elimination is through LDLR binding [167], although LDLR-independent mechanisms of PCSK9 clearance must exist [24]. Up to 30 % of PCSK9 is bound to LDL-C in mice [55, 167] and normolipidemic subjects [84]. In mice, PCSK9 is also bound to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) [55]. For the binding of PCSK9 to LDL-C the amino residues 31–52 of the PD are required [84].

PCSK9 is cleaved by furin as well as protein convertases (PC) 5/6 [15] between the amino acids Arg 218 and Gln 219 [52], and both forms of PCSK9 can be measured in human plasma [67]. Furin-cleaved PCSK9 (55 kDa) is still active and binds to the LDLR, however, with a twofold reduced activity [104]. Indeed, injection of furin-cleaved PCSK9 into mice results in increased LDL-C, as LDLR are downregulated [104].

PCSK9 binds to a variety of other proteins (for review, see [178]), one of them being annexin A2 which is present in the nucleus, the cytosol and the cell membrane in a variety of cells. The N-terminal repeat R1 of annexin 2 binds to the CHRD region of PCSK9 and inhibits its extracellular LDLR degrading activity [109]. In annexin A2 knockout mice plasma PCSK9 levels are doubled resulting in reduced LDLR expression and an increase in LDL-C [151]; thus annexin A2 is viewed as endogenous inhibitor of PCSK9 [109].

In summary, PCSK9 regulates the concentration of circulating low-density lipoproteins by enhancing the degradation of the hepatic LDLR that is required for hepatic LDL-C clearance.

Plasma concentration of PCSK9

The plasma concentration of PCSK9 follows a diurnal rhythm similar to cholesterol synthesis [28], with an increased plasma concentration in the morning and a lower concentration in the afternoon [125]. The plasma PCSK9 concentration is higher in women compared to men [90], and the PCSK9 concentrations decrease with age in men, but increase in women [11], most likely because elevated estrogen levels reduce PCSK9 expression [126]. Plasma PCSK9 concentration varies over a 50 [34]–100 [90] fold range [30–3,000 ng/ml] and plasma PCSK9 concentration correlates to plasma LDL-C concentration [4, 90] even in newborn infants [6]; in adults a 100 ng/ml increase in the plasma PCSK9 concentration will increase LDL-C by 0.20–0.25 mmol/l [92]. Lipid apheresis reduces plasma PCSK9 levels by 50 % [168], removing both the mature and the furin-cleaved form of PCSK9 [74].

Regulation of PCSK9 gene expression

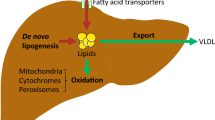

A number of transcription factors or cofactors regulate the PCSK9 gene expression (Fig. 3), including sterol-response element binding proteins (SREBP-1/2). Since the PCSK9 gene is regulated by sterols through SREBP2, low dietary cholesterol concentrations potently suppresses its expression and PCSK9 protein levels decrease in the course of fasting and increase after feeding in animals [175] and humans [23]. SREBP2 also controls LDLR expression.

Activation of PCSK9 expression can be mediated by activation of insulin receptors (Ins-R) and subsequent activation of the sterol-response element binding protein (SREBP) 1 and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways. Reduction of PCSK9 expression can be achieved by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) and activation of SREBP2. Secretion of PCSK9 can be attenuated by annexin A2. Plasma concentration of PCSK9 can be reduced by PPARα-dependent cleavage (requiring furin). High concentrations of PCSK9 down-regulate LDLR expression and favor the formation of oxidized (ox)-LDL. See text for more details

SREBP1 expression in hepatocytes is increased by insulin resulting in increased PCSK9 expression [39]. However, insulin can also activate the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)/protein kinase δ pathway thereby inhibiting hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α (HNF1α) resulting in less PCSK9 expression in hepatocytes [2]. Indeed, in HepG2 cells, hyperinsulinemia decreases PCSK9 expression, an effect which is also observed in post-menopausal obese women [9]. On the contrary, in healthy men 24 h hyperinsulinemia did not alter plasma PCSK9 concentrations [80] and PCSK9 expression is similar in normal, pre- and Typ2-diabetic patients [22]. Thus, the overall effect of insulin on PCSK9 expression appears to be neutral.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) regulates PCSK9 expression: PPARα reduces PCSK9 promoter activity thereby attenuating PCSK9 expression, while at the same time PPARα enhances furin/PC5/6 expression leading to increased cleavage of PCSK9 [85]. On the contrary, PPARγ increases PCSK9 expression in hepatocytes [50].

Other transcription factors or factors are the farnesoid X receptor (FXR, activated by bile acids, reduces PCSK9 expression) [93], the liver X receptor (LXR, activated by oxysterols, increases PCSK9 expression) [39, 148], and histone nuclear factor P (HINFP, increases PCSK9 expression) [100].

Also sirtuins 1 and 6 (SIRT1/6), critical histone deacetylases, suppress the PCSK9 gene [166], reduce PCSK9 secretion and increase hepatocyte LDLR expression [117] thereby modifying LDL-C homeostasis. Finally, the adipose tissue-derived adipokine resistin increases the PCSK9 expression and reduces LDLR expression in hepatocytes [116].

Ongoing studies will be instrumental for the understanding of the importance of the regulators of PCSK9 gene expression for serum LDL-C concentrations. In addition, further research is needed to address the expression of PCSK9 and its function in different compartments (e.g. blood, liver and intestine).

PCSK9 and inducible degrader of LDLR (IDOL)

IDOL is another protein which involved in the internalization and degradation of the LDLR [77, 144]. IDOL binds to the C-terminus of the LDLR [147, 148] and stimulates clathrin-independent endocytosis of the LDLR [147]. IDOL, which is activated through the LXR employs the endosomal sorting complex required for transport to traffic LDLR to the lysosomes [147]. IDOL can also stimulate SREBP2 thereby increasing PCSK9 expression again reducing LDLR expression. Individuals carrying an IDOL mutation (pArg266X) which results in a complete loss of IDOL function exhibit low serum LDL-C concentrations [156].

Drug-induced changes in PCSK9 expression

Given the number of transcription factors and co-factors regulating the PCSK9 gene it appears obvious that a number of drugs will affect PCSK9 expression (Table 1).

Statins increase the transcription factor SREBP2 [7] thereby increasing PCSK9 expression [7, 18, 138] dose-dependently [64] also in diabetic patients (otherwise having normal PCSK9 levels, see above) [29, 40, 120]. More recently, statins have been shown to increase HNF1α expression in hepatocytes, thereby increasing PCSK9 expression to a greater extent than LDLR expression [48]. Statins not only enhance the monomeric but also the heterodimeric form of PCSK9 [123]. The increase in PCSK9 expression following statin treatment is correlated to the statin-induced LDL-C decrease [10], and can be reversed by mevalonate treatment [51] or resistin treatment [116]. Such co-treatment therefore could enhance the LDL-C reducing effect of statins.

Fibrates activate PPARα thereby affecting PCSK9 expression [85]. Indeed, fibrates reduce PCSK9 expression in hepatocytes [110] and in patients [91]. However, the latter finding is controversial since fibrate treatment increased PCSK9 in another short-term patient study [169]; this discrepant finding can potentially be explained by the LDL-C lowering effect of fibrates leading to an increased PCSK9 expression (for review, see [12]).

Ezetimibe does not increase PCSK9 per se in healthy men [18]. However, ezetimibe through its plasma LDL-C concentration reducing effect might lead to a secondary increase of PCSK9 expression as measured in cynomolgus monkeys [68].

Cholesterylester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors, in contrast downregulate PCSK9 and LDLR expression through decreases in SREBP2 expression in hepatocytes [47].

Glitazones activate the extracellular-regulated kinases (ERK) 1 and 2 resulting in phosphorylation of PPARγ thereby reducing its activity; as PPARγ increases PCSK9 mRNA and protein expression in the liver, glitazones attenuate secretion of PCSK9 from hepatocytes [50].

Rapamycin, as an immunosuppressant, attenuates mTORC1 activation thereby increasing HNF1α activity and subsequently PCSK9 expression [2].

Berberine treatment decreases PCSK9 in hepatocytes associated with an inhibition of the transcription factor HNF1α [26, 99]. Interestingly, in in vivo studies, berberine treatment reduces dyslipidemia induced by LPS treatment which was associated with a reduction in the plasma PCSK9 concentration [177].

Disease-induced changes of PCSK9 expression

Inflammation stimulates PCSK9 expression in hepatocytes [54] and the plasma PCSK9 concentration is correlated to white blood cell count [102] and fibrinogen concentration [181] in patients. In patients with an acute myocardial infarction, the plasma PCSK9 concentration is elevated compared to stable coronary artery disease patients [5]. Similarly in proteinuric patients [87] and those with a nephrotic syndrome [79] an increase in plasma PCSK9 concentration occurs; part of this effect, however, might relate to the statin treatment of these patients.

PCSK9 mutations and LDL-C concentration

Alterations in the PCSK9 gene and/or PCSK9 GOF mutations are responsible in part for familiar hypercholesterolemia (FH) [106], including the autosomal dominant form. GOF mutations of PCSK9 [1, 15, 72] lead to hypercholesterolemia while non-sense mutations [1] or LOF-mutations [15, 17, 34, 45] reduce the LDL-C concentration (Fig. 1). GOF mutations are sometimes related to reduced furin cleavage of PCSK9 [52] while LOF-mutations relate to lack of PCSK9 phosphorylation and subsequent increased proteolysis [45]. For review, please refer to [170].

PCSK9 and cardiovascular disease

The GOF-mutation (D374Y) of PCSK9 causes severe hypercholesterolemia and development of profound atherosclerotic lesions in mice [137] and pigs [3]. PCSK9 overexpression increases LDL-C concentration in mice and accelerates the development of atherosclerosis, the latter being absent in LDLR-knockout mice [41]. On the contrary, development of atherosclerosis is slowed down by inactivation of the PCSK9 gene in mice [41]. These data were supported by Kühnast et al. [86] treating mice with increased atherogenesis with different doses of a PCSK9 inhibitor alone and in combination with atorvastatin. Alirocumab alone dose-dependently decreased serum cholesterol, reduced atherosclerotic lesion size and improved plaque morphology. These effects were enhanced when atorvastatin was added [86] (Fig. 4) but beneficial effects require both the presence of the LDLR and apoprotein E [8].

Correlation between average plasma TC and atherosclerotic lesion area in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice treated with different doses of the PCSK9 inhibitor alone and in combination with atorvastatin. Alirocumab dose-dependently decreased serum cholesterol, reduced atherosclerotic lesion size and improved plaque morphology. These effects were enhanced when atorvastatin was added. (modified from [86])

Development of atherosclerosis involves endothelial cell apoptosis and accumulation of foam cells, both of which can be triggered by oxidized LDL-C (oxLDL-C) [154, 165, 174]. Indeed, oxLDL-C increases PCSK9 expression in macrophages [165] and the oxLDL-C induced apoptosis is reduced in human umbilical vein endothelial cells by silencing PCSK9, an effect being related to less caspase 9 and 3 activation [174]. Also cholesterol uptake of THP-1 macrophages and foam cell formation as well as oxLDL-C/NFkB- induced inflammation are attenuated by PCSK9 silencing [165] (for review, see [154]).

In line with the above cell and animal experiments, the plasma PCSK9 concentration correlates with the intima-media thickness in patients [96], and GOF mutations of PCSK9 increase not only the LDL-C concentration but also the intima-media thickness over time compared to normal subjects [121]. Plasma PCSK9 concentrations are predictive for 4-5 year major cardiovascular event rate [76] and PCSK9 serum concentrations correlate with cardiovascular risk [95]. In patients with stable coronary artery disease (Fig. 5), higher PCSK9 concentrations were associated with increased cardiovascular events and with female gender, hypertension, statin treatment, C-reactive protein, HbA1c, insulin, total cholesterol and fasting triglycerides, but not with LDL- or HDL-cholesterol. Interestingly, the association of PCSK9 levels with cardiovascular events was reduced after adjustment for fasting triglycerides [173].

Number of primary outcome events (cardiovascular death and unplanned cardiovascular hospitalization) in 504 consecutive patients with stable coronary artery disease stratified by PCSK9 tertiles after 48 months. Increased PCSK9 serum concentrations correlate with outcomes. (modified from [173])

With high-dose statin treatment, however, the predictive value of PCSK9 is lost [76]. Mutations of PCSK9 leading to reduced expression and or function of PCSK9 are associated with a reduced rate of coronary heart disease [37] (Fig. 6), myocardial infarction [63] and overall cardiovascular events [143], an effect being more pronounced in black as compared to white subjects [37].

In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (ARIC), sequence variants of PCSK9 that are associated with reduced plasma LDL-C are associated with reduced risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). The figure depicts the results of n = 3363 black subjects: 2.6 % showed nonsense mutations in PCSK9; these mutations were associated with a 28 % reduction in mean LDL-C and a 88 % reduction in the risk of CHD. Of the 9,524 white subjects examined, 3.2 % had a sequence variation in PCSK9 that was associated with a 15 % reduction in LDL-C and a 47 % reduction in the risk of CHD (P = 0.003) (modified from [37])

Other receptors/channels/enzymes affected by PCSK9

Apart from its binding to LDLR, PCSK9 also interacts with other receptors such as the very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) [88, 127], the LDLR-related protein 1 (LRP1) [27], the apoprotein E receptor (ApoER) as well as CD81 on hepatocytes (hepatitis C virus receptor) [89] and CD36 on macrophages (for review, see [154]). Some interactions of PCSK9 with receptors depend on a EGF-A binding domain (VLDLR) [152] or require the catalytic activity of PCSK9 (LRP1). VLDLR and ApoER are also targeted by IDOL (for review, see [76]).

Lipoprotein (Lp) (a)

Clinical studies show that inhibition of PCSK9 potently lowers Lp(a), which is a strong cardiovascular risk factor [59, 159]. Currently, no drug treatment is available that lowers Lp(a) (with the exeption of nicotinic acid in some countries). Interestingly, PCSK9 inhibition reduces Lp(a) in patients with homozygous FH despite their lack or dysfunction of the LDLR. This effect was observed even in patients that are LDLR negative [159]. Therefore, the question arises whether the regulation of Lp(a) by PCSK9 may be independent of the LDLR. From this perspective, the modulation of VLDLR by PCSK9 appears to be of great interest since Lp(a) clearance by hepatocytes appears to depend on VLDLR expression [73]. Thus, reducing PCSK9 expression or receptor binding activity may mediate the reduction of Lp(a). The underlying molecular mechanism(s) are not fully understood. The following pathways may contribute:

-

Reduction of Apo(a) synthesis (in hepatocytes, release in circulation).

-

Reduction of ApoB or assembly (at outer hepatocyte surface).

-

Enhanced removal of Lp(a) in kidney, liver, peripheral tissues. Potential additional receptors for Lp(a) such as docking receptors, sorting receptors sortilin, endocytic receptors (syndecan-1 heparan sulfate proteoglycan).

-

Intestinal lipoprotein metabolism (please see below).

Epithelial ENaC

Expression at the cell surface is reduced by PCSK9. PCSK9—independent from its catalytic activity— the proteosomal degradation of ENaC prior to its membrane integration; interestingly and different from other receptor interactions, PCSK9 does not interfere with membrane-bound ENaC [153]. It has been speculated that GOF mutation of PCSK9 will therefore reduce membrane-bound ENaC expression leading to less sodium reabsorption and potentially less hypertension in the long-term. However, the clinical study programs of PCSK9 inhibiting antibodies have not shown signals of increased blood pressure to date.

Extra-hepatic expression and effects of PCSK9

Intestinal cholesterol absorption

Although the hepatic effects of PCSK9 appear to be the primary mechanism of action, PCSK9 in intestinal cells may play a very important role for the lipoprotein homeostasis. PCSK9 increases the expression of the apical cholesterol transporter (Niemann Pick C1 like 1, NPC1L1) in intestine epithelial cells [98]. Furthermore, PCSK9 enhances the intracellular expression of the apoprotein B48 (apoB48) [98, 135] and modifies the activities of the HMG-CoA reductase (decreased), the Acyl-CoA-Cholesterol-Transferase (ACAT, decreased) [98] and the microsomal transfer protein (MTP, increased) [98]. It also reduces the expression of the LDLR at the basolateral membrane of intestine epithelial cells [98]. PCSK9 promotes intestinal overproduction of triglyceride-rich apoB lipoproteins [135], and a reduction in PCSK9 leads to a reduced apoB48 expression, less triglycerides being transferred to apoB48 (via MTP inhibition) and prolonged storage and less secretion of triglycerides (via ACAT inhibition) from intestine epithelial cells. As a consequence postprandial triglyceridemia is reduced in PCSK9 knockout mice [95].

Furthermore, the transintestinal cholesterol excretion (TICE)—contributes up to 30 % of fecal neutral sterols excretion—is modulated by PCSK9. TICE is fuelled by apoprotein B containing particles such as LDL and also to a minor extent by HDL. TICE involves the active transporter ATP binding cassette transporter B1 on the apical membrane of enterocytes and the LDLR at its basolateral membrane [94]. PCSK9 through decreasing LDLR expression reduces TICE, as it had no impact in LDLR-knockout mice [94]. These findings may explain the correlation of PCSK9 with triglycerides in the serum [173].

PCSK9 in the brain

PCSK9 was initially discovered as a protein up-regulated during apoptosis of neurons [150]. PCSK9, that was formerly known as NARC-1 is important for brain development, especially the cerebellum [128]. Here, PCSK9 is thought to interact primarily with VLDLR and ApoER which are coupled to relin signaling and pro-apoptotic signaling pathways [88], although an interaction of PCSK9 with ApoER in brain tissue was questioned more recently [105]. PCSK9 is present in the cerebrospinal fluid at remarkably constant concentrations [33]. Brain tissue PCSK9 expression is increased with cerebral ischemia [88] and in brain tissue with signs of neuronal apoptosis [19], the latter being induced for example by increased oxLDL-C concentrations [176]. A relation to vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease is controversial, PCSK9 may be involved in degradation of β-site amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cleaving enzyme 1 and the generation of amyloid β-peptide.

The location of the “loss-of-function” single-nucleotide polymorphism rs11591147 (more commonly called R46L) is depicted in Fig. 1. In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (ARIC), the R46L mutation was associated with lower LDL-C and a reduced prevalence of peripheral arterial disease as well as a reduced risk of coronary heart disease [17, 37, 57]. Recently, the effects of LDL-C lowering mediated by PCSK9 inhibition on cognitive function have become a matter of debate [http://digitool.library.mcgill.ca/webclient/StreamGate?folder_id=0&dvs=1420384772483~463]. Jukema et al. therefore assessed the PCSK9 R46Lmutation within 5,777 participants of the PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) [129]. R46L was associated with 10–16 % lower LDL-C levels, but was not associated with cognitive performance, daily activities, or non-cardiovascular clinical events. The authors conclude “that lower cholesterol levels due to genetic variation in the PCSK9 gene are not associated with cognitive performance, functional status, or non-cardiovascular clinical events” [129].

PCSK9 in pancreatic ß-cells

PCSK9 and LDLR are also expressed in ß-cells. PCSK9-knockout mice carry more LDLR and less insulin in the pancreas, leading to hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance. ß-cell islets of PCSK9-knockout mice inhibit signs of inflammation and apoptosis [112]. This phenotype is modulated by gender and age [111]. Glucose tolerance is one of the parameters that will be carefully monitored in the outcome trials with PCSK9 inhibitors, so far the phase II data do not suggest the presence of this potential off-target effect in humans.

PCSK9 in adipose tissue

PCSK9-knockout mice have more visceral adipose tissue. Individual adipocytes are hypertrophied, most likely as a result of increased expression of VLDLR [141].

PCSK9 and innate immune response

Pathogen-associated lipids such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activate innate immune receptors inducing an inflammatory response, e.g. during sepsis. Mammalian lipid transfer proteins bind pathogen lipids. Interstingly, PCSK9 inhibited LPS uptake in human liver cells [171]. Inhibition of PCSK9 improved survival and inflammation in murine sepsis. The PCSK9 effect was abrogated in LDL receptor (LDLR) knockout mice. These data were confirmed in humans with PCSK9 loss-of-function genetic variants and in humans who are homozygous for an LDLR variant that is resistant to PCSK9. These data suggest that inhibition of PCSK9 mediates pathogen lipid clearance via the LDLR regulating systemic inflammatory response.

Therapeutic strategies to inhibit PCSK9

Anti-PCSK9 antibody treatment

Fully human antibodies directed against PCSK9 have been developed and are used in clinical trials (for detailed review, see [78]). These antibodies dose-dependently reduce plasma LDL-C and also lower the plasma Lp(a) concentration. Results of published trials are given in Table 2. However, new strategies to modify the PCSK9-LDLR interaction are in development (Table 3).

Partial antibodies/fragment antigen binding

Antibodies to PCSK9, binding to epitopes adjacent to the ones required for LDLR binding, increase LDLR expression in hepatocytes. This antibody administered to mice results in a significant reduction in plasma LDL-C concentration which is not seen in LDLR-knockout mice. The effect of antibody treatment on LDL-C is even more pronounced and prolonged in monkeys [30]. Similar results are obtained with antibodies covering the catalytic domain of PCSK9 otherwise binding the EGF-A domain of the LDLR [119, 180]; such treatment reduces the free plasma PCSK9 and LDL-C concentrations in rhesus monkeys [146]. Similarly, antibodies against the C-terminal domain lower LDL-C in cynomolgus monkeys [145].

Similar to antibodies, molecular scaffolds binding to PCSK9 close to its LDLR binding epitopes reduce the free PCSK9 and subsequently the LDL-C concentration in cynomolgus monkeys [118]. Such a molecular scaffold is adnectin (11 kDa), which is derived from human fibronectin.

Apart from the interaction with secreted PCSK9, interference can occur at the gene or mRNA level. Induction of loss-of-function mutations in mice, using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR-Cas9) genome editing, results in reduced plasma PCSK9 and LDL-C concentrations [155]. RNA interfering (RNAi) drugs attenuate PCSK9 synthesis and decrease plasma PCSK9 and LDL-C concentrations in rodents [58], primates [58] and healthy volunteers [56]. Locked nucleic acid (LNA) antisense oligonucleotide silences PCSK9 in vitro (hepatocytes) and in vivo (mice) subsequently reducing plasma PCSK9 and LDL-C concentrations [65]. Again, similar results are obtained in non-human primates where a single injection of LNA decreases LDL-C concentration for more than 4 weeks [103].

PCSK9 has both intracellular and extracellular functions which differ related to the cell type and organ. PCSK9 affects both receptor expression and intracellular enzyme function. Thus, antibodies directed against the secreted form of PCSK9—acting mainly extracellularly—will most likely lead to different results when compared to approaches resulting to LOF-mutation or gene knockout of PCSK9, both interfering PCSK9 intracellular and extracellular function. Epidemiological findings related to GOF- or LOF- mutations of PCSK9 may therefore not easily be transferred to recent antibody approaches.

In conclusion, effects of PCSK9 inhibitors in addition to the regulation of the LDLR expression clearly exist and may be beneficial. In the large on-going phase 3 programs using PCSK9 inhibitors, to date no “loss of safety”- signal has been observed. The primary effect of PSCK9 inhibition appears to be the up-regulation of hepatic LDLR but further basic science and clinical research will advance our understanding of how PCSK9 inhibition interferes with lipoprotein metabolism and improve cardiovascular outcome.

References

Abifadel M, Rabes JP, Boileau C, Varret M (2007) After the LDL receptor and apolipoprotein B, autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia reveals its third protagonist: PCSK9. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 68:138–146. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2007.02.002

Ai D, Chen C, Han S, Ganda A, Murphy AJ, Haeusler R, Thorp E, Accili D, Horton JD, Tall AR (2012) Regulation of hepatic LDL receptors by mTORC1 and PCSK9 in mice. J Clin Invest 122:1262–1270. doi:10.1172/JCI61919

Al-Mashhadi RH, Sorensen CB, Kragh PM, Christoffersen C, Mortensen MB, Tolbod LP, Thim T, Du Y, Li J, Liu Y, Moldt B, Schmidt M, Vajta G, Larsen T, Purup S, Bolund L, Nielsen LB, Callesen H, Falk E, Mikkelsen JG, Bentzon JF (2013) Familial hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in cloned minipigs created by DNA transposition of a human PCSK9 gain-of-function mutant. Sci Transl Med 5:166ra1. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004853

Alborn WE, Cao G, Careskey HE, Qian YW, Subramaniam DR, Davies J, Conner EM, Konrad RJ (2007) Serum proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 is correlated directly with serum LDL cholesterol. Clin Chem 53:1814–1819. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.091280

Almontashiri NA, Vilmundarson RO, Ghasemzadeh N, Dandona S, Roberts R, Quyyumi AA, Chen HH, Stewart AF (2014) Plasma PCSK9 levels are elevated with acute myocardial infarction in two independent retrospective angiographic studies. PLoS One 9:e106294. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106294

Araki S, Suga S, Miyake F, Ichikawa S, Kinjo T, Yamamoto Y, Kusuhara K (2014) Circulating PCSK9 levels correlate with the serum LDL cholesterol level in newborn infants. Early Hum Dev 90:607–611. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.07.013

Ason B, Tep S, Davis HR Jr, Xu Y, Tetzloff G, Galinski B, Soriano F, Dubinina N, Zhu L, Stefanni A, Wong KK, Tadin-Strapps M, Bartz SR, Hubbard B, Ranalletta M, Sachs AB, Flanagan WM, Strack A, Kuklin NA (2011) Improved efficacy for ezetimibe and rosuvastatin by attenuating the induction of PCSK9. J Lipid Res 52:679–687. doi:10.1194/jlr.M013664

Ason B, van der Hoorn JW, Chan J, Lee E, Pieterman EJ, Nguyen KK, Di M, Shetterly S, Tang J, Yeh WC, Schwarz M, Jukema JW, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Princen HM, Jackson S (2014) PCSK9 inhibition fails to alter hepatic LDLR, circulating cholesterol, and atherosclerosis in the absence of ApoE. J Lipid Res 55:2370–2379. doi:10.1194/jlr.M053207

Awan Z, Dubuc G, Faraj M, Dufour R, Seidah NG, Davignon J, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Baass A (2014) The effect of insulin on circulating PCSK9 in postmenopausal obese women. Clin Biochem 47:1033–1039. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.03.022

Awan Z, Seidah NG, MacFadyen JG, Benjannet S, Chasman DI, Ridker PM, Genest J (2012) Rosuvastatin, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 concentrations, and LDL cholesterol response: the JUPITER trial. Clin Chem 58:183–189. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2011.172932

Baass A, Dubuc G, Tremblay M, Delvin EE, O’Loughlin J, Levy E, Davignon J, Lambert M (2009) Plasma PCSK9 is associated with age, sex, and multiple metabolic markers in a population-based sample of children and adolescents. Clin Chem 55:1637–1645. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2009.126987

Beaudoin M, Lo KS, N’Diaye A, Rivas MA, Dube MP, Laplante N, Phillips MS, Rioux JD, Tardif JC, Lettre G (2012) Pooled DNA resequencing of 68 myocardial infarction candidate genes in French canadians. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 5:547–554. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.963165

Benjannet S, Hamelin J, Chretien M, Seidah NG (2012) Loss- and gain-of-function PCSK9 variants: cleavage specificity, dominant negative effects, and low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) degradation. J Biol Chem 287:33745–33755. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.399725

Benjannet S, Rhainds D, Essalmani R, Mayne J, Wickham L, Jin W, Asselin MC, Hamelin J, Varret M, Allard D, Trillard M, Abifadel M, Tebon A, Attie AD, Rader DJ, Boileau C, Brissette L, Chretien M, Prat A, Seidah NG (2004) NARC-1/PCSK9 and its natural mutants: zymogen cleavage and effects on the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor and LDL cholesterol. J Biol Chem 279:48865–48875. doi:10.1074/jbc.M409699200

Benjannet S, Rhainds D, Hamelin J, Nassoury N, Seidah NG (2006) The proprotein convertase (PC) PCSK9 is inactivated by furin and/or PC5/6A: functional consequences of natural mutations and post-translational modifications. J Biol Chem 281:30561–30572. doi:10.1074/jbc.M606495200

Benjannet S, Saavedra YG, Hamelin J, Asselin MC, Essalmani R, Pasquato A, Lemaire P, Duke G, Miao B, Duclos F, Parker R, Mayer G, Seidah NG (2010) Effects of the prosegment and pH on the activity of PCSK9: evidence for additional processing events. J Biol Chem 285:40965–40978. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.154815

Benn M, Nordestgaard BG, Grande P, Schnohr P, Tybjaerg-Hansen A (2010) PCSK9 R46L, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, and risk of ischemic heart disease: 3 independent studies and meta-analyses. J Am Coll Cardiol 55:2833–2842. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.044

Berthold HK, Seidah NG, Benjannet S, Gouni-Berthold I (2013) Evidence from a randomized trial that simvastatin, but not ezetimibe, upregulates circulating PCSK9 levels. PLoS One 8:e60095. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060095

Bingham B, Shen R, Kotnis S, Lo CF, Ozenberger BA, Ghosh N, Kennedy JD, Jacobsen JS, Grenier JM, DiStefano PS, Chiang LW, Wood A (2006) Proapoptotic effects of NARC 1 (=PCSK9), the gene encoding a novel serine proteinase. Cytometry A 69:1123–1131. doi:10.1002/cyto.a.20346

Blom DJ, Hala T, Bolognese M, Lillestol MJ, Toth PD, Burgess L, Ceska R, Roth E, Koren MJ, Ballantyne CM, Monsalvo ML, Tsirtsonis K, Kim JB, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Stein EA (2014) A 52-week placebo-controlled trial of evolocumab in hyperlipidemia. N Engl J Med 370:1809–1819. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1316222

Bottomley MJ, Cirillo A, Orsatti L, Ruggeri L, Fisher TS, Santoro JC, Cummings RT, Cubbon RM, Lo SP, Calzetta A, Noto A, Baysarowich J, Mattu M, Talamo F, De FR, Sparrow CP, Sitlani A, Carfi A (2009) Structural and biochemical characterization of the wild type PCSK9-EGF(AB) complex and natural familial hypercholesterolemia mutants. J Biol Chem 284:1313–1323. doi:10.1074/jbc.M808363200

Brouwers MC, Troutt JS, van Greevenbroek MM, Ferreira I, Feskens EJ, van der Kallen CJ, Schaper NC, Schalkwijk CG, Konrad RJ, Stehouwer CD (2011) Plasma proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 is not altered in subjects with impaired glucose metabolism and type 2 diabetes mellitus, but its relationship with non-HDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B may be modified by type 2 diabetes mellitus: the CODAM study. Atherosclerosis 217:263–267. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.03.023

Browning JD, Horton JD (2010) Fasting reduces plasma proprotein convertase, subtilisin/kexin type 9 and cholesterol biosynthesis in humans. J Lipid Res 51:3359–3363. doi:10.1194/jlr.P009860

Cameron J, Bogsrud MP, Tveten K, Strom TB, Holven K, Berge KE, Leren TP (2012) Serum levels of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 in subjects with familial hypercholesterolemia indicate that proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 is cleared from plasma by low-density lipoprotein receptor-independent pathways. Transl Res 160:125–130. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2012.01.010

Cameron J, Holla OL, Laerdahl JK, Kulseth MA, Berge KE, Leren TP (2009) Mutation S462P in the PCSK9 gene reduces secretion of mutant PCSK9 without affecting the autocatalytic cleavage. Atherosclerosis 203:161–165. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.007

Cameron J, Ranheim T, Kulseth MA, Leren TP, Berge KE (2008) Berberine decreases PCSK9 expression in HepG2 cells. Atherosclerosis 201:266–273. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.02.004

Canuel M, Sun X, Asselin MC, Paramithiotis E, Prat A, Seidah NG (2013) Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) can mediate degradation of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP-1). PLoS One 8:e64145. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064145

Cariou B, Langhi C, Le BM, Bortolotti M, Le KA, Theytaz F, Le MC, Guyomarc’h-Delasalle B, Zair Y, Kreis R, Boesch C, Krempf M, Tappy L, Costet P (2013) Plasma PCSK9 concentrations during an oral fat load and after short term high-fat, high-fat high-protein and high-fructose diets. Nutr Metab (Lond) 10:4. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-10-4

Cariou B, Le BM, Langhi C, Le MC, Guyomarc’h-Delasalle B, Krempf M, Costet P (2010) Association between plasma PCSK9 and gamma-glutamyl transferase levels in diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis 211:700–702. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.04.015

Chan JC, Piper DE, Cao Q, Liu D, King C, Wang W, Tang J, Liu Q, Higbee J, Xia Z, Di Y, Shetterly S, Arimura Z, Salomonis H, Romanow WG, Thibault ST, Zhang R, Cao P, Yang XP, Yu T, Lu M, Retter MW, Kwon G, Henne K, Pan O, Tsai MM, Fuchslocher B, Yang E, Zhou L, Lee KJ, Daris M, Sheng J, Wang Y, Shen WD, Yeh WC, Emery M, Walker NP, Shan B, Schwarz M, Jackson SM (2009) A proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 neutralizing antibody reduces serum cholesterol in mice and nonhuman primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:9820–9825. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903849106

Chen XW, Wang H, Bajaj K, Zhang P, Meng ZX, Ma D, Bai Y, Liu HH, Adams E, Baines A, Yu G, Sartor MA, Zhang B, Yi Z, Lin J, Young SG, Schekman R, Ginsburg D (2013) SEC24A deficiency lowers plasma cholesterol through reduced PCSK9 secretion. Elife 2:e00444. doi:10.7554/eLife.00444;00444

Chen Y, Wang H, Yu L, Yu X, Qian YW, Cao G, Wang J (2011) Role of ubiquitination in PCSK9-mediated low-density lipoprotein receptor degradation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 415:515–518. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.110

Chen YQ, Troutt JS, Konrad RJ (2014) PCSK9 is present in human cerebrospinal fluid and is maintained at remarkably constant concentrations throughout the course of the day. Lipids 49:445–455. doi:10.1007/s11745-014-3895-6

Chernogubova E, Strawbridge R, Mahdessian H, Malarstig A, Krapivner S, Gigante B, Hellenius ML, de FU, Franco-Cereceda A, Syvanen AC, Troutt JS, Konrad RJ, Eriksson P, Hamsten A, van ‘t Hooft FM (2012) Common and low-frequency genetic variants in the PCSK9 locus influence circulating PCSK9 levels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32:1526–1534. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.240549

Cho L, Rocco M, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, Rosenson RS, Dent R, Xue A, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Stroes E (2014) Design and rationale of the GAUSS-2 study trial: a double-blind, ezetimibe-controlled phase 3 study of the efficacy and tolerability of evolocumab (AMG 145) in subjects with hypercholesterolemia who are intolerant of statin therapy. Clin Cardiol 37:131–139. doi:10.1002/clc.22248

Chorba JS, Shokat KM (2014) The proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) active site and cleavage sequence differentially regulate protein secretion from proteolysis. J Biol Chem 289:29030–29043. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.594861

Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH Jr, Hobbs HH (2006) Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 354:1264–1272. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054013

Colhoun HM, Robinson JG, Farnier M, Cariou B, Blom D, Kereiakes DJ, Lorenzato C, Pordy R, Chaudhari U (2014) Efficacy and safety of alirocumab, a fully human PCSK9 monoclonal antibody, in high cardiovascular risk patients with poorly controlled hypercholesterolemia on maximally tolerated doses of statins: rationale and design of the ODYSSEY COMBO I and II trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 14:121. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-14-121

Costet P, Cariou B, Lambert G, Lalanne F, Lardeux B, Jarnoux AL, Grefhorst A, Staels B, Krempf M (2006) Hepatic PCSK9 expression is regulated by nutritional status via insulin and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c. J Biol Chem 281:6211–6218. doi:10.1074/jbc.M508582200

Costet P, Hoffmann MM, Cariou B, Guyomarc’h DB, Konrad T, Winkler K (2010) Plasma PCSK9 is increased by fenofibrate and atorvastatin in a non-additive fashion in diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis 212:246–251. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.05.027

Denis M, Marcinkiewicz J, Zaid A, Gauthier D, Poirier S, Lazure C, Seidah NG, Prat A (2012) Gene inactivation of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 reduces atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation 125:894–901. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.057406

Desai NR, Giugliano RP, Zhou J, Kohli P, Somaratne R, Hoffman E, Liu T, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Sabatine MS (2014) AMG 145, a monoclonal antibody against PCSK9, facilitates achievement of national cholesterol education program-adult treatment panel III low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals among high-risk patients: an analysis from the LAPLACE-TIMI 57 trial (LDL-C assessment with PCSK9 monoclonal antibody inhibition combined with statin thErapy-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 57). J Am Coll Cardiol 63:430–433. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.048

Desai NR, Kohli P, Giugliano RP, O’Donoghue ML, Somaratne R, Zhou J, Hoffman EB, Huang F, Rogers WJ, Wasserman SM, Scott R, Sabatine MS (2013) AMG145, a monoclonal antibody against proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9, significantly reduces lipoprotein(a) in hypercholesterolemic patients receiving statin therapy: an analysis from the LDL-C Assessment with Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin Kexin Type 9 Monoclonal Antibody Inhibition Combined with Statin Therapy (LAPLACE)-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 57 trial. Circulation 128:962–969. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001969

DeVay RM, Shelton DL, Liang H (2013) Characterization of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) trafficking reveals a novel lysosomal targeting mechanism via amyloid precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2). J Biol Chem 288:10805–10818. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.453373

Dewpura T, Raymond A, Hamelin J, Seidah NG, Mbikay M, Chretien M, Mayne J (2008) PCSK9 is phosphorylated by a Golgi casein kinase-like kinase ex vivo and circulates as a phosphoprotein in humans. FEBS J 275:3480–3493. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06495.x

Dias CS, Shaywitz AJ, Wasserman SM, Smith BP, Gao B, Stolman DS, Crispino CP, Smirnakis KV, Emery MG, Colbert A, Gibbs JP, Retter MW, Cooke BP, Uy ST, Matson M, Stein EA (2012) Effects of AMG 145 on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels: results from 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose phase 1 studies in healthy volunteers and hypercholesterolemic subjects on statins. J Am Coll Cardiol 60:1888–1898. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.986

Dong B, Wu M, Cao A, Li H, Liu J (2011) Suppression of Idol expression is an additional mechanism underlying statin-induced up-regulation of hepatic LDL receptor expression. Int J Mol Med 27:103–110. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2010.559

Dong B, Wu M, Li H, Kraemer FB, Adeli K, Seidah NG, Park SW, Liu J (2010) Strong induction of PCSK9 gene expression through HNF1alpha and SREBP2: mechanism for the resistance to LDL-cholesterol lowering effect of statins in dyslipidemic hamsters. J Lipid Res 51:1486–1495. doi:10.1194/jlr.M003566

Du F, Hui Y, Zhang M, Linton MF, Fazio S, Fan D (2011) Novel domain interaction regulates secretion of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) protein. J Biol Chem 286:43054–43061. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.273474

Duan Y, Chen Y, Hu W, Li X, Yang X, Zhou X, Yin Z, Kong D, Yao Z, Hajjar DP, Liu L, Liu Q, Han J (2012) Peroxisome Proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation by ligands and dephosphorylation induces proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 and low density lipoprotein receptor expression. J Biol Chem 287:23667–23677. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.350181

Dubuc G, Chamberland A, Wassef H, Davignon J, Seidah NG, Bernier L, Prat A (2004) Statins upregulate PCSK9, the gene encoding the proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase-1 implicated in familial hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24:1454–1459. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000134621.14315.43

Essalmani R, Susan-Resiga D, Chamberland A, Abifadel M, Creemers JW, Boileau C, Seidah NG, Prat A (2011) In vivo evidence that furin from hepatocytes inactivates PCSK9. J Biol Chem 286:4257–4263. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.192104

Fan D, Yancey PG, Qiu S, Ding L, Weeber EJ, Linton MF, Fazio S (2008) Self-association of human PCSK9 correlates with its LDLR-degrading activity. Biochemistry 47:1631–1639. doi:10.1021/bi7016359

Feingold KR, Moser AH, Shigenaga JK, Patzek SM, Grunfeld C (2008) Inflammation stimulates the expression of PCSK9. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 374:341–344. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.023

Fisher TS, Lo SP, Pandit S, Mattu M, Santoro JC, Wisniewski D, Cummings RT, Calzetta A, Cubbon RM, Fischer PA, Tarachandani A, De FR, Wright SD, Sparrow CP, Carfi A, Sitlani A (2007) Effects of pH and low density lipoprotein (LDL) on PCSK9-dependent LDL receptor regulation. J Biol Chem 282:20502–20512. doi:10.1074/jbc.M701634200

Fitzgerald K, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Shulga-Morskaya S, Liebow A, Bettencourt BR, Sutherland JE, Hutabarat RM, Clausen VA, Karsten V, Cehelsky J, Nochur SV, Kotelianski V, Horton J, Mant T, Chiesa J, Ritter J, Munisamy M, Vaishnaw AK, Gollob JA, Simon A (2014) Effect of an RNA interference drug on the synthesis of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and the concentration of serum LDL cholesterol in healthy volunteers: a randomised, single-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet 383:60–68. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61914-5

Folsom AR, Peacock JM, Boerwinkle E (2007) Sequence variation in proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 serine protease gene, low LDL cholesterol, and cancer incidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16:2455–2458. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0502

Frank-Kamenetsky M, Grefhorst A, Anderson NN, Racie TS, Bramlage B, Akinc A, Butler D, Charisse K, Dorkin R, Fan Y, Gamba-Vitalo C, Hadwiger P, Jayaraman M, John M, Jayaprakash KN, Maier M, Nechev L, Rajeev KG, Read T, Rohl I, Soutschek J, Tan P, Wong J, Wang G, Zimmermann T, de FA, Vornlocher HP, Langer R, Anderson DG, Manoharan M, Koteliansky V, Horton JD, Fitzgerald K (2008) Therapeutic RNAi targeting PCSK9 acutely lowers plasma cholesterol in rodents and LDL cholesterol in nonhuman primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:11915–11920. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805434105

Gaudet D, Kereiakes DJ, McKenney JM, Roth EM, Hanotin C, Gipe D, Du Y, Ferrand AC, Ginsberg HN, Stein EA (2014) Effect of alirocumab, a monoclonal proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 antibody, on lipoprotein(a) concentrations (a pooled analysis of 150 mg every two weeks dosing from phase 2 trials). Am J Cardiol 114:711–715. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.05.060

Giugliano RP, Desai NR, Kohli P, Rogers WJ, Somaratne R, Huang F, Liu T, Mohanavelu S, Hoffman EB, McDonald ST, Abrahamsen TE, Wasserman SM, Scott R, Sabatine MS (2012) Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 in combination with a statin in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (LAPLACE-TIMI 57): a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 study. Lancet 380:2007–2017. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61770-X

Grozdanov PN, Petkov PM, Karagyozov LK, Dabeva MD (2006) Expression and localization of PCSK9 in rat hepatic cells. Biochem Cell Biol 84:80–92. doi:10.1139/o05-155

Gu HM, Adijiang A, Mah M, Zhang DW (2013) Characterization of the role of EGF-A of low density lipoprotein receptor in PCSK9 binding. J Lipid Res 54:3345–3357. doi:10.1194/jlr.M041129

Guella I, Asselta R, Ardissino D, Merlini PA, Peyvandi F, Kathiresan S, Mannucci PM, Tubaro M, Duga S (2010) Effects of PCSK9 genetic variants on plasma LDL cholesterol levels and risk of premature myocardial infarction in the Italian population. J Lipid Res 51:3342–3349. doi:10.1194/jlr.M010009

Guo YL, Liu J, Xu RX, Zhu CG, Wu NQ, Jiang LX, Li JJ (2013) Short-term impact of low-dose atorvastatin on serum proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9. Clin Drug Investig 33:877–883. doi:10.1007/s40261-013-0129-2

Gupta N, Fisker N, Asselin MC, Lindholm M, Rosenbohm C, Orum H, Elmen J, Seidah NG, Straarup EM (2010) A locked nucleic acid antisense oligonucleotide (LNA) silences PCSK9 and enhances LDLR expression in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 5:e10682. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010682

Gustafsen C, Kjolby M, Nyegaard M, Mattheisen M, Lundhede J, Buttenschon H, Mors O, Bentzon JF, Madsen P, Nykjaer A, Glerup S (2014) The hypercholesterolemia-risk gene SORT1 facilitates PCSK9 secretion. Cell Metab 19:310–318. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2013.12.006

Han B, Eacho PI, Knierman MD, Troutt JS, Konrad RJ, Yu X, Schroeder KM (2014) Isolation and characterization of the circulating truncated form of PCSK9. J Lipid Res 55:1505–1514. doi:10.1194/jlr.M049346

Hentze H, Jensen KK, Chia SM, Johns DG, Shaw RJ, Davis HR Jr, Shih SJ, Wong KK (2013) Inverse relationship between LDL cholesterol and PCSK9 plasma levels in dyslipidemic cynomolgus monkeys: effects of LDL lowering by ezetimibe in the absence of statins. Atherosclerosis 231:84–90. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.08.028

Hirayama A, Honarpour N, Yoshida M, Yamashita S, Huang F, Wasserman SM, Teramoto T (2014) Effects of evolocumab (AMG 145), a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, in hypercholesterolemic, statin-treated Japanese patients at high cardiovascular risk–primary results from the phase 2 YUKAWA study. Circ J 78:1073–1082 (DN/JST.JSTAGE/circj/CJ-14-0130 [pii])

Holla OL, Cameron J, Tveten K, Strom TB, Berge KE, Laerdahl JK, Leren TP (2011) Role of the C-terminal domain of PCSK9 in degradation of the LDL receptors. J Lipid Res 52:1787–1794. doi:10.1194/jlr.M018093

Holla OL, Laerdahl JK, Strom TB, Tveten K, Cameron J, Berge KE, Leren TP (2011) Removal of acidic residues of the prodomain of PCSK9 increases its activity towards the LDL receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 406:234–238. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.023

Homer VM, Marais AD, Charlton F, Laurie AD, Hurndell N, Scott R, Mangili F, Sullivan DR, Barter PJ, Rye KA, George PM, Lambert G (2008) Identification and characterization of two non-secreted PCSK9 mutants associated with familial hypercholesterolemia in cohorts from New Zealand and South Africa. Atherosclerosis 196:659–666. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.07.022

Hoover-Plow J, Huang M (2013) Lipoprotein(a) metabolism: potential sites for therapeutic targets. Metabolism 62:479–491. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2012.07.024

Hori M, Ishihara M, Yuasa Y, Makino H, Yanagi K, Tamanaha T, Kishimoto I, Kujiraoka T, Hattori H, Harada-Shiba M (2014) Removal of plasma mature and furin-cleaved proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) by low-density lipoprotein-apheresis in familial hypercholesterolemia: development and application of a new assay for PCSK9. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-3066

Horton JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH (2007) Molecular biology of PCSK9: its role in LDL metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci 32:71–77. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.12.008

Huijgen R, Boekholdt SM, Arsenault BJ, Bao W, Davaine JM, Tabet F, Petrides F, Rye KA, DeMicco DA, Barter PJ, Kastelein JJ, Lambert G (2012) Plasma PCSK9 levels and clinical outcomes in the TNT (Treating to New Targets) trial: a nested case-control study. J Am Coll Cardiol 59:1778–1784. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.043

Ishibashi M, Masson D, Westerterp M, Wang N, Sayers S, Li R, Welch CL, Tall AR (2010) Reduced VLDL clearance in Apoe(-/-)Npc1(-/-) mice is associated with increased Pcsk9 and Idol expression and decreased hepatic LDL-receptor levels. J Lipid Res 51:2655–2663. doi:10.1194/jlr.M006163

Jelassi A, Najah M, Slimani A, Jguirim I, Slimane MN, Varret M (2013) Autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia: needs for early diagnosis and cascade screening in the tunisian population. Curr Genomics 14:25–32. doi:10.2174/138920213804999200

Jin K, Park BS, Kim YW, Vaziri ND (2014) Plasma PCSK9 in nephrotic syndrome and in peritoneal dialysis: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis 63:584–589. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.042

Kappelle PJ, Lambert G, Dullaart RP (2011) Plasma proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 does not change during 24 h insulin infusion in healthy subjects and type 2 diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis 214:432–435. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.10.028

Koren MJ, Giugliano RP, Raal FJ, Sullivan D, Bolognese M, Langslet G, Civeira F, Somaratne R, Nelson P, Liu T, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Sabatine MS (2014) Efficacy and safety of longer-term administration of evolocumab (AMG 145) in patients with hypercholesterolemia: 52-week results from the Open-Label Study of Long-Term Evaluation Against LDL-C (OSLER) randomized trial. Circulation 129:234–243. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007012

Koren MJ, Lundqvist P, Bolognese M, Neutel JM, Monsalvo ML, Yang J, Kim JB, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Bays H (2014) Anti-PCSK9 monotherapy for hypercholesterolemia: The MENDEL-2 randomized, controlled phase III clinical trial of evolocumab. J Am Coll Cardiol 63:2531–2540. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.018

Koren MJ, Scott R, Kim JB, Knusel B, Liu T, Lei L, Bolognese M, Wasserman SM (2012) Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 as monotherapy in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (MENDEL): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet 380:1995–2006. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61771-1

Kosenko T, Golder M, Leblond G, Weng W, Lagace TA (2013) Low density lipoprotein binds to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type-9 (PCSK9) in human plasma and inhibits PCSK9-mediated low density lipoprotein receptor degradation. J Biol Chem 288:8279–8288. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.421370

Kourimate S, Le MC, Langhi C, Jarnoux AL, Ouguerram K, Zair Y, Nguyen P, Krempf M, Cariou B, Costet P (2008) Dual mechanisms for the fibrate-mediated repression of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9. J Biol Chem 283:9666–9673. doi:10.1074/jbc.M705831200

Kuhnast S, van der Hoorn JW, Pieterman EJ, van den Hoek AM, Sasiela WJ, Gusarova V, Peyman A, Schafer HL, Schwahn U, Jukema JW, Princen HM (2014) Alirocumab inhibits atherosclerosis, improves the plaque morphology, and enhances the effects of a statin. J Lipid Res 55:2103–2112. doi:10.1194/jlr.M051326

Kwakernaak AJ, Lambert G, Slagman MC, Waanders F, Laverman GD, Petrides F, Dikkeschei BD, Navis G, Dullaart RP (2013) Proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 is elevated in proteinuric subjects: relationship with lipoprotein response to antiproteinuric treatment. Atherosclerosis 226:459–465. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.11.009

Kysenius K, Muggalla P, Matlik K, Arumae U, Huttunen HJ (2012) PCSK9 regulates neuronal apoptosis by adjusting ApoER2 levels and signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 69:1903–1916. doi:10.1007/s00018-012-0977-6

Labonte P, Begley S, Guevin C, Asselin MC, Nassoury N, Mayer G, Prat A, Seidah NG (2009) PCSK9 impedes hepatitis C virus infection in vitro and modulates liver CD81 expression. Hepatology 50:17–24. doi:10.1002/hep.22911

Lakoski SG, Lagace TA, Cohen JC, Horton JD, Hobbs HH (2009) Genetic and metabolic determinants of plasma PCSK9 levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:2537–2543. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-0141

Lambert G, Ancellin N, Charlton F, Comas D, Pilot J, Keech A, Patel S, Sullivan DR, Cohn JS, Rye KA, Barter PJ (2008) Plasma PCSK9 concentrations correlate with LDL and total cholesterol in diabetic patients and are decreased by fenofibrate treatment. Clin Chem 54:1038–1045. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.099747

Lambert G, Petrides F, Chatelais M, Blom DJ, Choque B, Tabet F, Wong G, Rye KA, Hooper AJ, Burnett JR, Barter PJ, Marais AD (2014) Elevated plasma PCSK9 level is equally detrimental for patients with nonfamilial hypercholesterolemia and heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, irrespective of low-density lipoprotein receptor defects. J Am Coll Cardiol 63:2365–2373. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.538

Langhi C, Le MC, Kourimate S, Caron S, Staels B, Krempf M, Costet P, Cariou B (2008) Activation of the farnesoid X receptor represses PCSK9 expression in human hepatocytes. FEBS Lett 582:949–955. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.038

Le MC, Berger JM, Lespine A, Pillot B, Prieur X, Letessier E, Hussain MM, Collet X, Cariou B, Costet P (2013) Transintestinal cholesterol excretion is an active metabolic process modulated by PCSK9 and statin involving ABCB1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33:1484–1493. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300263

Le MC, Kourimate S, Langhi C, Chetiveaux M, Jarry A, Comera C, Collet X, Kuipers F, Krempf M, Cariou B, Costet P (2009) Proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 null mice are protected from postprandial triglyceridemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29:684–690. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181586

Lee CJ, Lee YH, Park SW, Kim KJ, Park S, Youn JC, Lee SH, Kang SM, Jang Y (2013) Association of serum proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 with carotid intima media thickness in hypertensive subjects. Metabolism 62:845–850. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2013.01.005

Leren TP (2004) Mutations in the PCSK9 gene in Norwegian subjects with autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Clin Genet 65:419–422. doi:10.1111/j.0009-9163.2004.0238.x

Levy E, Ben Djoudi OA, Spahis S, Sane AT, Garofalo C, Grenier E, Emonnot L, Yara S, Couture P, Beaulieu JF, Menard D, Seidah NG, Elchebly M (2013) PCSK9 plays a significant role in cholesterol homeostasis and lipid transport in intestinal epithelial cells. Atherosclerosis 227:297–306. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.01.023

Li H, Dong B, Park SW, Lee HS, Chen W, Liu J (2009) Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1alpha plays a critical role in PCSK9 gene transcription and regulation by the natural hypocholesterolemic compound berberine. J Biol Chem 284:28885–28895. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.052407

Li H, Liu J (2012) The novel function of HINFP as a co-activator in sterol-regulated transcription of PCSK9 in HepG2 cells. Biochem J 443:757–768. doi:10.1042/BJ20111645

Li J, Tumanut C, Gavigan JA, Huang WJ, Hampton EN, Tumanut R, Suen KF, Trauger JW, Spraggon G, Lesley SA, Liau G, Yowe D, Harris JL (2007) Secreted PCSK9 promotes LDL receptor degradation independently of proteolytic activity. Biochem J 406:203–207. doi:10.1042/BJ20070664

Li S, Guo YL, Xu RX, Zhang Y, Zhu CG, Sun J, Qing P, Wu NQ, Jiang LX, Li JJ (2014) Association of plasma PCSK9 levels with white blood cell count and its subsets in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 234:441–445. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.04.001

Lindholm MW, Elmen J, Fisker N, Hansen HF, Persson R, Moller MR, Rosenbohm C, Orum H, Straarup EM, Koch T (2012) PCSK9 LNA antisense oligonucleotides induce sustained reduction of LDL cholesterol in nonhuman primates. Mol Ther 20:376–381. doi:10.1038/mt.2011.260

Lipari MT, Li W, Moran P, Kong-Beltran M, Sai T, Lai J, Lin SJ, Kolumam G, Zavala-Solorio J, Izrael-Tomasevic A, Arnott D, Wang J, Peterson AS, Kirchhofer D (2012) Furin-cleaved proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is active and modulates low density lipoprotein receptor and serum cholesterol levels. J Biol Chem 287:43482–43491. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.380618

Liu M, Wu G, Baysarowich J, Kavana M, Addona GH, Bierilo KK, Mudgett JS, Pavlovic G, Sitlani A, Renger JJ, Hubbard BK, Fisher TS, Zerbinatti CV (2010) PCSK9 is not involved in the degradation of LDL receptors and BACE1 in the adult mouse brain. J Lipid Res 51:2611–2618. doi:10.1194/jlr.M006635

Mabuchi H, Nohara A, Noguchi T, Kobayashi J, Kawashiri MA, Inoue T, Mori M, Tada H, Nakanishi C, Yagi K, Yamagishi M, Ueda K, Takegoshi T, Miyamoto S, Inazu A, Koizumi J (2014) Genotypic and phenotypic features in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia caused by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) gain-of-function mutation. Atherosclerosis 236:54–61. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.06.005

Maxwell KN, Breslow JL (2004) Adenoviral-mediated expression of Pcsk9 in mice results in a low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:7100–7105. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402133101

Maxwell KN, Fisher EA, Breslow JL (2005) Overexpression of PCSK9 accelerates the degradation of the LDLR in a post-endoplasmic reticulum compartment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:2069–2074. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409736102

Mayer G, Poirier S, Seidah NG (2008) Annexin A2 is a C-terminal PCSK9-binding protein that regulates endogenous low density lipoprotein receptor levels. J Biol Chem 283:31791–31801. doi:10.1074/jbc.M805971200

Mayne J, Dewpura T, Raymond A, Cousins M, Chaplin A, Lahey KA, Lahaye SA, Mbikay M, Ooi TC, Chretien M (2008) Plasma PCSK9 levels are significantly modified by statins and fibrates in humans. Lipids Health Dis 7:22. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-7-22

Mbikay M, Sirois F, Gyamera-Acheampong C, Wang GS, Rippstein P, Chen A, Mayne J, Scott FW, Chretien M (2014) Variable effects of gender and Western diet on lipid and glucose homeostasis in aged PCSK9-deficient C57BL/6 mice. J Diabetes. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.12139

Mbikay M, Sirois F, Mayne J, Wang GS, Chen A, Dewpura T, Prat A, Seidah NG, Chretien M, Scott FW (2010) PCSK9-deficient mice exhibit impaired glucose tolerance and pancreatic islet abnormalities. FEBS Lett 584:701–706. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.018

McKenney JM, Koren MJ, Kereiakes DJ, Hanotin C, Ferrand AC, Stein EA (2012) Safety and efficacy of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 serine protease, SAR236553/REGN727, in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia receiving ongoing stable atorvastatin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 59:2344–2353. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.007

McNutt MC, Kwon HJ, Chen C, Chen JR, Horton JD, Lagace TA (2009) Antagonism of secreted PCSK9 increases low density lipoprotein receptor expression in HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem 284:10561–10570. doi:10.1074/jbc.M808802200

McNutt MC, Lagace TA, Horton JD (2007) Catalytic activity is not required for secreted PCSK9 to reduce low density lipoprotein receptors in HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem 282:20799–20803. doi:10.1074/jbc.C700095200

Melone M, Wilsie L, Palyha O, Strack A, Rashid S (2012) Discovery of a new role of human resistin in hepatocyte low-density lipoprotein receptor suppression mediated in part by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9. J Am Coll Cardiol 59:1697–1705. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.064

Miranda MX, van Tits LJ, Lohmann C, Arsiwala T, Winnik S, Tailleux A, Stein S, Gomes AP, Suri V, Ellis JL, Lutz TA, Hottiger MO, Sinclair DA, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K, Staels B, Luscher TF, Matter CM (2014) The Sirt1 activator SRT3025 provides atheroprotection in Apoe-/- mice by reducing hepatic Pcsk9 secretion and enhancing Ldlr expression. Eur Heart J. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu095

Mitchell T, Chao G, Sitkoff D, Lo F, Monshizadegan H, Meyers D, Low S, Russo K, DiBella R, Denhez F, Gao M, Myers J, Duke G, Witmer M, Miao B, Ho SP, Khan J, Parker RA (2014) Pharmacologic profile of the adnectin BMS-962476, a small protein biologic alternative to PCSK9 antibodies for low-density lipoprotein lowering. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 350:412–424. doi:10.1124/jpet.114.214221

Ni YG, Di MS, Condra JH, Peterson LB, Wang W, Wang F, Pandit S, Hammond HA, Rosa R, Cummings RT, Wood DD, Liu X, Bottomley MJ, Shen X, Cubbon RM, Wang SP, Johns DG, Volpari C, Hamuro L, Chin J, Huang L, Zhao JZ, Vitelli S, Haytko P, Wisniewski D, Mitnaul LJ, Sparrow CP, Hubbard B, Carfi A, Sitlani A (2011) A PCSK9-binding antibody that structurally mimics the EGF(A) domain of LDL-receptor reduces LDL cholesterol in vivo. J Lipid Res 52:78–86. doi:10.1194/jlr.M011445

Noguchi T, Kobayashi J, Yagi K, Nohara A, Yamaaki N, Sugihara M, Ito N, Oka R, Kawashiri MA, Tada H, Takata M, Inazu A, Yamagishi M, Mabuchi H (2011) Comparison of effects of bezafibrate and fenofibrate on circulating proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 and adipocytokine levels in dyslipidemic subjects with impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from a crossover study. Atherosclerosis 217:165–170. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.02.012

Norata GD, Garlaschelli K, Grigore L, Raselli S, Tramontana S, Meneghetti F, Artali R, Noto D, Cefalu AB, Buccianti G, Averna M, Catapano AL (2010) Effects of PCSK9 variants on common carotid artery intima media thickness and relation to ApoE alleles. Atherosclerosis 208:177–182. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.06.023

Norata GD, Tibolla G, Catapano AL (2014) Targeting PCSK9 for hypercholesterolemia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 54:273–293. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-140025

Nozue T, Hattori H, Ishihara M, Iwasaki T, Hirano T, Kawashiri MA, Yamagishi M, Michishita I (2013) Comparison of effects of pitavastatin versus pravastatin on serum proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 levels in statin-naive patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 111:1415–1419. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.01.289

Park SW, Moon YA, Horton JD (2004) Post-transcriptional regulation of low density lipoprotein receptor protein by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9a in mouse liver. J Biol Chem 279:50630–50638. doi:10.1074/jbc.M410077200

Persson L, Cao G, Stahle L, Sjoberg BG, Troutt JS, Konrad RJ, Galman C, Wallen H, Eriksson M, Hafstrom I, Lind S, Dahlin M, Amark P, Angelin B, Rudling M (2010) Circulating proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 has a diurnal rhythm synchronous with cholesterol synthesis and is reduced by fasting in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30:2666–2672. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.214130

Persson L, Henriksson P, Westerlund E, Hovatta O, Angelin B, Rudling M (2012) Endogenous estrogens lower plasma PCSK9 and LDL cholesterol but not Lp(a) or bile acid synthesis in women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32:810–814. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242461

Poirier S, Mayer G, Benjannet S, Bergeron E, Marcinkiewicz J, Nassoury N, Mayer H, Nimpf J, Prat A, Seidah NG (2008) The proprotein convertase PCSK9 induces the degradation of low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and its closest family members VLDLR and ApoER2. J Biol Chem 283:2363–2372. doi:10.1074/jbc.M708098200

Poirier S, Prat A, Marcinkiewicz E, Paquin J, Chitramuthu BP, Baranowski D, Cadieux B, Bennett HP, Seidah NG (2006) Implication of the proprotein convertase NARC-1/PCSK9 in the development of the nervous system. J Neurochem 98:838–850. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03928.x

Postmus I, Trompet S, de Craen AJ, Buckley BM, Ford I, Stott DJ, Sattar N, Slagboom PE, Westendorp RG, Jukema JW (2013) PCSK9 SNP rs11591147 is associated with low cholesterol levels but not with cognitive performance or noncardiovascular clinical events in an elderly population. J Lipid Res 54:561–566. doi:10.1194/jlr.P033969

Qian YW, Schmidt RJ, Zhang Y, Chu S, Lin A, Wang H, Wang X, Beyer TP, Bensch WR, Li W, Ehsani ME, Lu D, Konrad RJ, Eacho PI, Moller DE, Karathanasis SK, Cao G (2007) Secreted PCSK9 downregulates low density lipoprotein receptor through receptor-mediated endocytosis. J Lipid Res 48:1488–1498. doi:10.1194/jlr.M700071-JLR200

Raal F, Scott R, Somaratne R, Bridges I, Li G, Wasserman SM, Stein EA (2012) Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering effects of AMG 145, a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 serine protease in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: the Reduction of LDL-C with PCSK9 Inhibition in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia Disorder (RUTHERFORD) randomized trial. Circulation 126:2408–2417. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.144055

Raal FJ, Giugliano RP, Sabatine MS, Koren MJ, Langslet G, Bays H, Blom D, Eriksson M, Dent R, Wasserman SM, Huang F, Xue A, Albizem M, Scott R, Stein EA (2014) Reduction in lipoprotein(a) with PCSK9 monoclonal antibody evolocumab (AMG 145): a pooled analysis of more than 1,300 patients in 4 phase II trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 63:1278–1288. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.006

Raal FJ, Honarpour N, Blom DJ, Hovingh GK, Xu F, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Stein EA (2014) Inhibition of PCSK9 with evolocumab in homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (TESLA Part B): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61374-X

Raal FJ, Stein EA, Dufour R, Turner T, Civeira F, Burgess L, Langslet G, Scott R, Olsson AG, Sullivan D, Hovingh GK, Cariou B, Gouni-Berthold I, Somaratne R, Bridges I, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Gaudet D (2014) PCSK9 inhibition with evolocumab (AMG 145) in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (RUTHERFORD-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61399-4

Rashid S, Tavori H, Brown PE, Linton MF, He J, Giunzioni I, Fazio S (2014) Proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 promotes intestinal overproduction of triglyceride-rich apolipoprotein B lipoproteins through both low-density lipoprotein receptor-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Circulation 130:431–441. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006720

Robinson JG, Nedergaard BS, Rogers WJ, Fialkow J, Neutel JM, Ramstad D, Somaratne R, Legg JC, Nelson P, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Weiss R (2014) Effect of evolocumab or ezetimibe added to moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy on LDL-C lowering in patients with hypercholesterolemia: the LAPLACE-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 311:1870–1882. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.4030

Roche-Molina M, Sanz-Rosa D, Cruz FM, Garcia-Prieto J, Lopez S, Abia R, Muriana FJ, Fuster V, Ibanez B, Bernal JA (2014) Induction of sustained hypercholesterolemia by single adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer of mutant hPCSK9. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35:50–59. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303617

Romano M, Di Taranto MD, D’Agostino MN, Marotta G, Gentile M, Abate G, Mirabelli P, Di NR, Del VL, Rubba P, Fortunato G (2010) Identification and functional characterization of LDLR mutations in familial hypercholesterolemia patients from Southern Italy. Atherosclerosis 210:493–496. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.11.051

Roth EM, McKenney JM, Hanotin C, Asset G, Stein EA (2012) Atorvastatin with or without an antibody to PCSK9 in primary hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 367:1891–1900. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1201832

Roth EM, Taskinen MR, Ginsberg HN, Kastelein JJ, Colhoun HM, Robinson JG, Merlet L, Pordy R, Baccara-Dinet MT (2014) Monotherapy with the PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab versus ezetimibe in patients with hypercholesterolemia: Results of a 24 week, double-blind, randomized Phase 3 trial. Int J Cardiol 176:55–61. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.06.049

Roubtsova A, Munkonda MN, Awan Z, Marcinkiewicz J, Chamberland A, Lazure C, Cianflone K, Seidah NG, Prat A (2011) Circulating proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) regulates VLDLR protein and triglyceride accumulation in visceral adipose tissue. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31:785–791. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.220988

Saavedra YG, Day R, Seidah NG (2012) The M2 module of the Cys-His-rich domain (CHRD) of PCSK9 protein is needed for the extracellular low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) degradation pathway. J Biol Chem 287:43492–43501. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.394023

Saavedra YG, Dufour R, Davignon J, Baass A (2014) PCSK9 R46L, lower LDL, and cardiovascular disease risk in familial hypercholesterolemia: A cross-sectional cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304406

Sasaki M, Terao Y, Ayaori M, Uto-Kondo H, Iizuka M, Yogo M, Hagisawa K, Takiguchi S, Yakushiji E, Nakaya K, Ogura M, Komatsu T, Ikewaki K (2014) Hepatic overexpression of idol increases circulating protein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 in mice and hamsters via dual mechanisms: sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 and low-density lipoprotein receptor-dependent pathways. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34:1171–1178. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302670

Schiele F, Park J, Redemann N, Luippold G, Nar H (2014) An antibody against the C-terminal domain of PCSK9 lowers LDL cholesterol levels in vivo. J Mol Biol 426:843–852. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2013.11.011

Schroeder CI, Swedberg JE, Withka JM, Rosengren KJ, Akcan M, Clayton DJ, Daly NL, Cheneval O, Borzilleri KA, Griffor M, Stock I, Colless B, Walsh P, Sunderland P, Reyes A, Dullea R, Ammirati M, Liu S, McClure KF, Tu M, Bhattacharya SK, Liras S, Price DA, Craik DJ (2014) Design and synthesis of truncated EGF-A peptides that restore LDL-R recycling in the presence of PCSK9 in vitro. Chem Biol 21:284–294. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.11.014

Scotti E, Calamai M, Goulbourne CN, Zhang L, Hong C, Lin RR, Choi J, Pilch PF, Fong LG, Zou P, Ting AY, Pavone FS, Young SG, Tontonoz P (2013) IDOL stimulates clathrin-independent endocytosis and multivesicular body-mediated lysosomal degradation of the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Mol Cell Biol 33:1503–1514. doi:10.1128/MCB.01716-12

Scotti E, Hong C, Yoshinaga Y, Tu Y, Hu Y, Zelcer N, Boyadjian R, de Jong PJ, Young SG, Fong LG, Tontonoz P (2011) Targeted disruption of the idol gene alters cellular regulation of the low-density lipoprotein receptor by sterols and liver x receptor agonists. Mol Cell Biol 31:1885–1893. doi:10.1128/MCB.01469-10

Seidah NG (2011) The proprotein convertases, 20 years later. Methods Mol Biol 768:23–57. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-204-5_3

Seidah NG, Benjannet S, Wickham L, Marcinkiewicz J, Jasmin SB, Stifani S, Basak A, Prat A, Chretien M (2003) The secretory proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1): liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:928–933. doi:10.1073/pnas.0335507100

Seidah NG, Poirier S, Denis M, Parker R, Miao B, Mapelli C, Prat A, Wassef H, Davignon J, Hajjar KA, Mayer G (2012) Annexin A2 is a natural extrahepatic inhibitor of the PCSK9-induced LDL receptor degradation. PLoS One 7:e41865. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041865

Shan L, Pang L, Zhang R, Murgolo NJ, Lan H, Hedrick JA (2008) PCSK9 binds to multiple receptors and can be functionally inhibited by an EGF-A peptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 375:69–73. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.106

Sharotri V, Collier DM, Olson DR, Zhou R, Snyder PM (2012) Regulation of epithelial sodium channel trafficking by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9). J Biol Chem 287:19266–19274. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.363382

Shen L, Peng HC, Nees SN, Zhao SP, Xu DY (2013) Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 potentially influences cholesterol uptake in macrophages and reverse cholesterol transport. FEBS Lett 587:1271–1274. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2013.02.027