Abstract

The tendency for women in Canada and the United States to report being more satisfied than men with their jobs is considered paradoxical because women, on average, receive fewer job-related resources than men. Theory and research suggest that the magnitude of the gender difference that underlies that paradox may increase as levels of negative affect increase. Using data from people living and working in Toronto, Canada, this study evaluates hypotheses about the joint association of gender and two forms of negative affect, anxiety and demoralization, with job satisfaction. Data collected in telephone interviews are analyzed using ordinal probit regression. As job satisfaction decreases with increasing negative affect, the size of the gender difference in job satisfaction increases. When job characteristics indicative of job quality are controlled, the interaction between gender and demoralization is reduced to a non-significant level, but the interaction between gender and anxiety changes little, and remains significant. The results are interpreted as indicating that as negative affect increases, women are more likely to reference standards that counterbalance decreases in their satisfaction (e.g., standards linked to “communion” with co-workers), and men are more likely to reference standards that further decrease their satisfaction (e.g., standards linked to relative advantage). The persistence of the interaction between gender and anxiety after job characteristics are controlled suggests that anxiety-provoking experiences outside of the workplace may contribute to the gender difference in job satisfaction. The associations among quality of work, demoralization, and job satisfaction are stronger among men than women, explaining the interaction of gender with demoralization.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bäzner, E., Brömer, P., Hammelstein, P., & Meyer, T. D. (2006). Current and former depression and their relationship to the effects of social comparison processes. Results of an internet based study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 93, 97–103. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.017.

Belansky, E. S., & Boggiano, A. K. (1994). Predicting helping behaviors: The role of gender and instrumental/expressive self-schemata. Sex Roles, 30, 647–661. doi:10.1007/BF01544668.

Bird, S. R. (2003). Sex composition, masculinity stereotype dissimilarity and the quality of men’s workplace social relations. Gender, Work and Organization, 10, 579–604. doi:10.1111/1468-0432.00212.

Brown, G. W., Harris, T. O., & Eales, M. J. (1996). Social factors and comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 168(Suppl 30), 50–57.

Buchanan, T. (2008). The same-sex-referent-work satisfaction relationship: assessing the mediating role of distributive justice perceptions. Sociological Focus, 41, 177–196.

Burleson, B., Hanasono, L., Bodie, G., Holmstrom, A., Rack, J., & Gill Rosier, J. (2009). Explaining recipient responses to supportive messages. Sex Roles, 16, 265–280. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9623-7.

Butzer, B., & Kuiper, N. A. (2006). Relationships between the frequency of social comparisons and self-concept clarity, intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety, and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 167–176. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.017.

Buunk, A. P., & Gibbons, F. X. (2006). Social comparison orientation: A new perspective on those who do and who don’t compare to others. In S. Guimond (Ed.), Social comparison and social psychology: Understanding cognition, intergroup relations, and culture (pp. 15–32). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Buunk, A. P., Zurriaga, R., & Peíro, J. M. (2010). Social comparison as a predictor of changes in burnout among nurses. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal, 23, 181–194. doi:10.1080/10615800902971521.

Côté, J. E. (2000). Arrested adulthood: The changing nature of maturity and identity. New York: New York University Press.

Cranford, C. J. (2012). Gendered projects of solidarity: Workplace organizing among immigrant. Gender, Work & Organization, 19, 142–164. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2011.00585.x.

Cranford, C. J., Vosko, L. F., & Zukewich, N. (2003). The gender of precarious employment in Canada. Relations Industrielles, 58, 454–479. doi:10.7202/007495ar.

Crosby, F. (1982). Relative deprivation and working women. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cross, S. E., Hardin, E. E., & Gercek-Swing, B. (2011). The what, how, why, and where of self-construal. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 142–179. doi:10.1177/1088868310373752.

De Sousa, R. (1987). The rationality of emotion. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

de Visser, L., van der Knaap, L., van de Loo, A., van der Weerd, C., Ohl, F., & van den Bos, R. (2010). Trait anxiety affects decision-making differently in healthy men and women: Towards gender-specific endophenotypes of anxiety. Neuropsychologia, 48, 1598–1606. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.01.027.

Dyke, L. S., & Murphy, S. A. (2006). How we define success: A qualitative study of what matters most to women and men. Sex Roles, 55, 357–371. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9091-2.

Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., & Diekman, A. B. (2000). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. In T. Eckes, H. M. Trautner, A. E. Abele, M. Andra, & D. Bukatko (Eds.), The developmental social psychology of gender (pp. 123–174). Abingdon. Florence: Psychology Press [Imprint]. Taylor & Francis Group.

Förster, J., & Dannenberg, L. (2010). GLOMOsys: Specifications of a global model on processing styles. Psychological Inquiry, 21, 257–269. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2010.507989.

Gardner, W. L., Gabriel, S., & Hochschild, L. (2002). When you and I are “We”, you are not threatening: The role of self-expansion in social comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 239–251. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.82.2.239.

Garson, G.D. (2011). Reliability analysis. Retrieved from http://faculty.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/PA765/reliab.htm.

Goffman, E. (1986). In Northeastern University Press (Ed.), Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Goldstein, B. I. (2006). Why do women get depressed and men get drunk? An examination of attributional style and coping style in response to negative life events among Canadian young adults. Sex Roles, 54, 27–37. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-8867-8.

Hagan, J., & Kay, F. (2007). Even lawyers get the blues: Gender, depression, and job satisfaction in legal practice. Law & Society Review, 41, 51–78. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5893.2007.00291.x.

Harris, R. J., Firestone, J. M., & Bryan, P. J. (2006). A comparative analysis of sex role ideology in Canada, Mexico and the United States. In V. Demos & M. T. Segal (Eds.), Advances in gender research (Vol. 10, pp. 97–123). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. doi:10.1016/S1529-2126(06)10005-3.

Hochschild, A. R. (1997). The time bind: When work becomes home and home becomes work (1st ed.). New York: Metropolitan Books.

Hodson, R. (1989). Gender differences in job satisfaction: Why aren’t women more dissatisfied? The Sociological Quarterly, 30, 385–399. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1989.tb01527.x.

Hughes, K., Lowe, G.S., Schellenberg, G. (2003). Men’s and women’s quality of work in the new Canadian economy. Research paper W|19. Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Networks. Retrieved from http://www.cprn.org/doc.cfm?doc=66&l=en.

Hulbert, K. D. (1993). Reflections on the lives of educated women. In K. D. Hulbert & D. T. Schuster (Eds.), Women’s lives through time: Educated American women of the twentieth century (pp. 417–443). San Francisco: JosseyBass.

Isbell, L. M. (2010). What is the relationship between affect and information-processing styles?: This and other global and local questions inspired by GLOMOsys. Psychological Inquiry, 21, 225–232. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2010.503794.

Jackson, A., & Kumar, P. (1998). Measuring and monitoring the quality of jobs and the work environment in Canada. Paper presented at the CSLS Conference on the State of Living Standards and the Quality of Life in Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.csls.ca/events/oct98/jacks.pdf.

Judge, T. A., Hulin, C. L., & Dalal, R. S. (2012). Job satisfaction and job affect. In S. W. J. Kozlowski (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of organizational psychology (pp. 496–525). New York: Oxford University Press.

Karasek, R., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books.

Kendall, M. G., & Gibbons, J. D. (1990). Rank Correlation Methods (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Konrad, A. M., Ritchie, J. E. J., Lieb, P., & Corrigall, E. (2000). Sex differences and similarities in job attribute preferences: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 593–625. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.126.4.593.

Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., & Neter, J. (2004). Applied linear regression models (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Lance, C. E., Mallard, A. G., & Michalos, A. C. (1995). Tests of the causal directions of global-life facet satisfaction relationships. Social Indicators Research, 34, 69–92. doi:10.1007/BF01078968.

Lowe, G. (2007). 21st century job quality: Achieving what Canadians want. Research Report W|37. Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Networks. Retrieved from http://www.cprn.org/doc.cfm?doc=1745&l=en.

Magee, W., & St-Arnaud, S. (2012). Models of the joint structure of domain-related and global distress: Implications for the reconciliation of quality of life and mental health perspectives. Social Indicators Research, 105, 1–25. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9771-8.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

Mirowsky, J. (1996). Age and the gender gap in depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 37, 362–380.

Moore, H. A. (1985). Job satisfaction and women’s spheres of work. Sex Roles, 13, 663–678. doi:10.1007/BF00287302.

Mueller, C. W., & Wallace, J. E. (1996). Justice and the paradox of the contented female worker. Social Psychology Quarterly, 59, 338–349. doi:10.2307/2787075.

Nabi, R. L., & Oliver, M. B. (2009). The SAGE handbook of media processes and effects. Los Angeles: Sage.

Neil, C. C., & Snizek, W. E. (1987). Work values, job characteristics, and gender. Sociological Perspectives, 30, 245–265. doi:10.2307/1389112.

Nippert-Eng, C. E. (1995). Home and work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nussbaum, M. (2001). Symposium on Amartya Sen’s Philosophy: 5 Adaptive preferences and women’s options. Economics and Philosophy, 17, 67–88. doi:10.1017/S0266267101000153.

Ojeda, V. D., Frank, R. G., Mcguire, T. G., & Gilmer, T. P. (2010). Mental illness, nativity, gender and labor supply. Health Economics, 19, 396–421. doi:10.1002/hec.1480.

Oldham, G. R., & Hackman, J. R. (2010). Not what it was and not what it will be: The future of job design research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 463–479. doi:10.1002/job.678.

Phelan, J. (1994). The paradox of the contented female worker: An assessment of alternative explanations. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 95–107. doi:10.2307/2786704.

Poirier, D. J. (1978). The use of the Box-Cox transformation in limited dependent variable models. Toronto: Institute for Policy Analysis, University of Toronto.

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–102. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001.

Schwalbe, M. L., & Staples, C. L. (1991). Gender differences in sources of self-esteem. Social Psychology Quarterly, 54, 158–168.

Sekaran, U. (1986). Significant differences in quality-of-life factors and their correlates: a function of differences in career orientations or gender? Sex Roles, 14, 261–279. doi:10.1007/BF00287578.

Sheldon, K. M., & Schuler, J. (2011). Needing, wanting, and having: Integrating motive disposition theory and self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 1106–1123. doi:10.1037/a0024952.

Shields, M. (2006). Unhappy on the job. Health Reports. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada.

Sousa-Poza, A., & Sousa-Poza, A. A. (2000). Taking another look at the gender/job-satisfaction paradox. Kyklos, 53, 135–152. doi:10.1111/1467-6435.00114.

StataCorp. (2011). Stata Statistical Software (Version Release 12). College Station, Texas: Statacorp LP.

Statistics Canada. (2006a) Employment Income Groups (23) in Constant (2005) Dollars, Age Groups (7A), Work Activity in the Reference Year (3), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Mother Tongue (6) and Sex (3) for the Population 15 Years and Over of Canada, 2000 and 2005 - 20% Sample Data. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/tbt/Lp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=0&PRID=0&PTYPE=88971,97154&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=811&Temporal=2006&THEME=81&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=.

Statistics Canada. (2006b). Educational portrait of Canada, 2006 Census: Census metropolitan areas (CMAs). Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/as-sa/97-560/p37-eng.cfm.

Statistics Canada. (2009). Visible minority population, by census metropolitan areas (2006 Census): (Kingston, Peterborough, Oshawa, Toronto, Hamilton). Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo53c-eng.htm.

Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., & Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7, 242–264. doi:10.1037//1076-8998.7.3.242.

Tellegen, A., Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1999). On The Dimensional And Hierarchical Structure Of Affect. Psychological Science, 10, 297–303. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00157.

Tesser, A. (1991). Emotion in social comparison and reflection processes. In J. Suls & T. A. Wills (Eds.), Social comparison: Contemporary theory and research (pp. 117–145). Hillsdale, NH: Erlbaum.

Thagard, P., & Nerb, J. (2002). Emotional gestalts: appraisal, change, and the dynamics of affect. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6, 274–282. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0604_02.

Vliegenthart, R., & van Zoonen, L. (2011). Power to the frame: Bringing sociology back to frame analysis. European Journal of Communication, 26, 101–115. doi:10.1177/0267323111404838.

Wegge, J., van Dick, R., Fisher, G. K., West, M. A., & Dawson, J. F. (2006). A test of basic assumptions of affective events theory (AET) in call centre work. British Journal of Management, 17, 237–254. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00489.x.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (Vol. 18, pp. 1–74). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Williams, R. (2009). Using heterogeneous choice models to compare logit and probit coefficients across groups. Sociological Methods & Research, 37, 531–559. doi:10.1177/0049124109335735.

Wright, E. O., Baxter, J., & Gunn, E. B. (1995). The gender gap in workplace authority: A cross-national study. American Sociological Review, 60, 407–435. doi:10.2307/2096422.

Zalewska, A. M. (2011). Relationships between anxiety and job satisfaction—Three approaches: ‘Bottom-up’, ‘top-down’ and ‘transactional’. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 977–986. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.013.

Acknowledgments

Data collection was funded by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. I wish to thank the editor, Dr. Frieze, and the two anonymous reviewers for extensive feedback and suggestions that substantially improved the paper. Thanks also to Lesley Kenny and Sherri Klassen for editorial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A: Evaluating the Hypothesis that a Two-Factor Model Specifying Correlated Latent Factors for Global Anxiety and Global Demoralization will Fit Better Than a Single Factor Model

Appendix A: Evaluating the Hypothesis that a Two-Factor Model Specifying Correlated Latent Factors for Global Anxiety and Global Demoralization will Fit Better Than a Single Factor Model

Studies have found anxiety and depressive moods to constitute the negative poles of distinct dimensions of global affect (Tellegen, Watson, & Clark, 1999). The ability to empirically differentiate between these two dimensions depends on the measures of each. In order to determine if the two dimensions can be differentiated in the current data a confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) is conducted. The correlations analyzed in this analysis are presented in Table 4, along with correlations with measures of job-related affect. Kendall’s Tau-b coefficients (Kendall & Gibbons, 1990) are presented since response scales are ordinal and skewed. Empirical distinguishability of work-related affect from global affect has been demonstrated in a previous report using these data (Magee and St-Arnaud 2012).

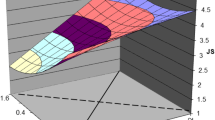

The fit of two CFA models are compared in Table 5. One model specifies a single latent factor for global negative affect, indicated by responses to all five of the global affect items. The other model specifies two latent factors with separate indicators of global demoralization (two-indicators) and global stress/anxiety (three indicators). Both analyses specify that loadings of indicators on latent factors are gender invariant. However, the correlation between the two latent factors in the two-factor model is free to vary by gender. Estimates are obtained from the asymptotic distribution-free (ADF) estimator in Stata 12 (StataCorp 2011). That estimator does not require that joint normality or the assumption of symmetry in item distributions.

By all fit criteria, the two-factor model fits the data well, and the single factor model does not fit the data at all. In addition, score-tests from the two-factor model indicate that there would be no gain from estimating models with different loadings for men and women (i.e., all tests are non-significant). Studies that have more extensively assessed anxiety, though, suggest that men and women may experience different symptoms of anxiety (de Visser, et al. 2010).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Magee, W. Anxiety, Demoralization, and the Gender Difference in Job Satisfaction. Sex Roles 69, 308–322 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0297-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0297-9