Abstract

We examine the process of romantic attraction in same-gender relationships using open and closed-ended questionnaire data from a sample of 120 men and women in Northern California. Agreeableness (e.g., kind, supportive) and Extraversion (e.g., fun, sense of humor) are the two most prominent bases of attraction, followed by Physical Attractiveness (e.g., appearance, sexy). The least important attractors represent traits associated with material success (e.g., financially secure, nice house). We also find evidence of seemingly contradictory attraction processes documented previously in heterosexual romantic relationships, in which individuals become disillusioned with the qualities in a partner that were initially appealing. Our findings challenge common stereotypes of same-gender relationships. The results document broad similarities between same-gender and cross-gender couples in attraction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stereotypes of men and women in intimate, same-gender relationships circulate in our society and play a role in the hotly contested debate concerning the legitimacy of gay marriage (Elections 1992; Herek 2008). The language of current anti-gay measures conveys the message that same-gender relationships and the people in them are deviant. These characterizations incorporate a number of untested assumptions, including the supposition that physical attraction takes an unusually prominent role in the romantic attraction process among same-gender couples (See Herek 1991; Herek and Berrill, 1990). Yet such assumptions receive little scholarly attention. One main goal of this research is to examine the degree to which these stereotypes are reflected in romantic attraction among individuals in lesbian and gay relationships in Northern California. We base our arguments on socio-cultural theories of gender (e.g., Bem 1993) and social exchange perspectives on attraction (e.g., Thibault and Kelley, 1959) and examine our research questions and hypotheses with an analysis of closed and open-ended questionnaire data.

Numerous studies address the question of attraction in relationships and find that several factors, such as similarity and proximity, draw two people together to form friendships and heterosexual romantic relationships (Graziano and Bruce 2008; Sprecher and Felmlee 2008). Nevertheless, relatively little research exists on attraction within intimate same-gender relationships. According to a review of the literature by Peplau and Spalding (2000), during the period from 1980 to 1993, only a tiny fraction of articles in two relationship-oriented social science journals, Journal of Marriage and the Family (less than .2%) and Journal of Social and Personal Relationships (less than 1%), dealt with sexual orientation in some way. Another goal of this research, therefore, is to extend the study of the attraction process to same-gender relationships. Do the same theories and processes of attraction apply to romance between those of the same gender?

This study uses questionnaire data gathered from a sample of individuals involved in same-gender relationships to examine the qualities that initially attracted these individuals to a romantic partner. We rely on both quantitative and qualitative data in our analyses. We begin by investigating the qualities that individuals report as attracting them to their intimate partner, and we employ factor analysis to identify the underlying dimensions of these attractors. Next we examine differences between men and women in terms of these attractors and factors. In addition, we investigate the traits that individuals report as now being “excessive” in their intimate partner. Finally, we examine a process of attraction and disenchantment that has been documented in heterosexual relationships, sometimes referred to as “fatal attraction” (See Felmlee 1998, 2001; Pines 1997, 2005).

Lesbian and Gay Stereotypes

Public opinion about gay men and lesbians has become more positive since the 1970’s (e.g., Hicks and Lee 2006; Stotzer 2009). Nevertheless, there exist substantial levels of institutional and personal hostility towards homosexuals in the U.S. and a number of negative stereotypes persist (Herek 1991). The existing scholarly literature on gay men and lesbians documents several common stereotypes, including the following: exhibition of gender atypical traits, sexual promiscuity, and predatory sexual tendencies. For example, one common public perception is that homosexuals manifest gender atypical traits or roles (Golebiowska 2001; Herek 1991; Patterson 1995a; Patterson 1995b; Patterson 2000; Simon 1998). Americans perceive gay men as gentle, passive, effeminate, and well-dressed (Gurwitz and Marcus 1978; Haddock et al. 1993; Madon 1997; Taywaditep 2001; Glick et al. 2007) and believe that gay men violate acceptable male gender roles (Madon 1997; Glick et al. 2007). Common stereotypes of lesbians emphasize the exhibition of excessive masculinity and a disinterest in traditional feminine pursuits and appearance (Geiger et al. 2006; LaMar and Kite 1998; Patterson 2000; Wilkinson 2008). Other stereotypes characterize homosexuals as sexually promiscuous and sexual predators (Bernstein 1997; Herek 1991; Simon 1998). Gay men, in particular, are labeled as predatory and promiscuous, with an inability to develop long-term intimate relationships (Golebiowska 2002; Golebiowska 2003; LaMar and Kite 1998; Madon 1997).

Variations of stereotypes also exist. Peplau (1991) discusses (and debunks) the stereotype that gay men and lesbians do not desire enduring relationships, which represents a variant of the promiscuity stereotype. Another version of this stereotype espouses the belief that homosexuals have unusually high sex drives (Herek 1991; Levitt and Klassen 1974). Moreover, a number of heterosexuals perceive gay men and lesbians as psychologically maladjusted, as well as obsessed with sex and incapable of forming committed relationships, although there is evidence to the contrary (Herek 1991). According to Herek (2004, 2007), such “sexual stigma” are based on biased cognitive processes, such as the recall of stereotype-confirming information, and therefore illustrate a form of sexual prejudice. These individual-level prejudices represent what Patricia Hill Collins refers to as “sexual repression” when they enter into and shape public discourse on sexuality and act to limit sexual alternatives (Alex-Assensoh 2005). Furthermore, prejudice towards gays and lesbians also extends across international borders (e.g., Heaven and Oxman 1999; Plummer 2001), a fact displayed most vividly, perhaps, in cases of homophobic violence documented across Europe, Australia, and the Americas (e.g., Comstock 1991; Sandroussi and Thompson 1995).

Note that the stereotyping of gay men and lesbians often conflates sexual orientation/identity with gender role performance. That is, traditional culturally constructed gender roles are presumed to be both desirable and consistent across the spectrum of human sexual identities. A common theme in our culture is that sex, sexuality, and gender are congruent with each other and fixed over the life course (Lorber 1996). Beginning in infancy, we are classified as either male or female based on the physical appearance of our external genitalia. Judith Butler (1999) refers to this binary categorization as the “discrete and asymmetrical oppositions between ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine,’ where these terms are understood as expressive attributes of ‘male’ and ‘female’.” In other words, our society associates gender and sexuality with biological sex, and assumes that behavioral expectations necessarily align with one of the two binary gender categories to which one is assigned. Feminist scholars, on the other hand, maintain that gender and sexuality are socially constructed through individuals’ thoughts, feelings, and social interactions, rather than the sole product of biological forces (Bem 1993; Butler 1999).

The idea of the male-female binary underlies another societal stereotype, one that asserts that there are dual gender roles in both same- and cross-gender relationships. According to this stereotype, each partner takes on either the masculine or feminine role to complement the other. Furthermore, the assumption is made that individuals whose sexuality is not oriented towards the cross gender are likely to display gendered behavior that is inconsistent with their biological sex. Hence, the notion of effeminate gay men and masculine lesbian women holds sway in the popular imagination. These stereotypes are not consistent with research findings (e.g., Peplau and Spalding 2000; Kurdek 2004).

Implicit in these stereotypes are assumptions regarding the social dynamics of the romantic relationships between two men or two women. In particular, relationships are believed to be short term and largely based on excessively strong sexual desires (see Peplau 1993; Sartore and Cunningham 2009). Popular conceptualizations of any non-physical traits of attraction reify ideas about dual masculine-feminine partner roles or transgressive gender-role performances (i.e., effeminate men or butch women). It is these relationship specific stereotypes that we address in our work.

Romantic Attraction

The process of romantic attraction is the subject of investigation in numerous research studies (e.g., Orbuch and Sprecher 2003), and the bulk of this research focuses on attraction among heterosexuals. Historically, the initial focus of research was on attraction between heterosexual strangers who met for the first time (Berscheid and Hatfield 1969). More recent research examines the attraction process among individuals in ongoing heterosexual relationships. Some of the main predictors of attraction include: proximity or propinquity, similarity or homogamy, physical attractiveness, and reciprocal liking (for a review of the literature see Orbuch and Sprecher 2003). An additional factor is familiarity, sometimes labeled “the most basic principle of attraction,” (Berscheid and Reis 1998), because it is thought to explain the association of several other factors with attraction, such as proximity and similarity. Desirable characteristics of the other, social influences (e.g., social network approval), and need-fulfillment are additional predictors of attraction commonly mentioned in reviews (Aron et al. 1989; Sprecher and Felmlee 2008). The three factors of desirable personality, physical appearance, and reciprocal liking appear in cross-cultural studies based on self-reports in several different societies (Sprecher et al. 1994).

Social exchange theory (Cook and Emerson 1987; Molm 1997; Thibault and Kelley 1959) represents one of the most prominent perspectives used in accounting for interpersonal attraction. According to exchange theory, individuals are apt to become attracted to one another when the rewards offered by a potential partner are greater than the costs, and when the rewards exceed those of feasible alternatives. Rewards refer to the pleasurable and gratifying consequences we obtain from being with another person, as well as the access provided to desired goods, such as money, status, and beauty. Costs are the negative and undesirable components of relationships, such as financial investments, interpersonal conflict, and the potential for pain and anguish. Subtracting anticipated costs from the anticipated rewards of a relationship generates the likely relationship outcome associated with a particular potential partner.

People use two standards to evaluate potential outcomes, according to the exchange perspective (Kelley and Thibaut 1978; Thibault and Kelley, 1959). The comparison level comprises one standard that people employ to evaluate a particular relationship, and it refers to the outcomes an individual expects to receive from a relationship based on past experiences. A potential relationship that falls below an individual’s comparison level is less likely to be satisfying than one that promises to be above it. The other standard is the comparison level for alternatives, which represents the level of outcomes an individual can expect to receive from available alternative relationships. An individual’s evaluation of his or her relationship depends on the opportunities for alternative partnerships that an individual faces. For example, someone may reject a potential romantic partner who appears to be promising, because she or he perceives better chances with a different person.

What differences, if any, might there be in the attraction process from a social exchange perspective for individuals in cross-gender relationships and those in same-gender relationships? The fundamental processes of social exchange should operate in similar ways. Individuals in either type of relationship would be expected to consider the rewards, costs, and outcomes and compare those to outcomes from previous relationships and to those that might be obtained in alternative situations (See Peplau and Fingerhut 2007). On the other hand, the content and level of the components of the theory could differ, depending on the sexual composition of the couple. For example, relationship costs for men and women in same-gender relationships are apt to be much higher than those facing the average heterosexual couple, due to the ever present specter of discrimination and homophobic prejudice. Higher costs may inhibit relationship formation in the first place and/or lead to relatively elevated breakup rates for same-gender couples. Yet there are likely to be fewer potential same-gender partners available in our society, as compared to the number available to individuals seeking cross-gender partners, suggesting that the average comparison level for alternatives for homosexuals will be relatively constricted. Individuals may be less likely to reject viable, potential partners in such situations.

Same-Gender Romantic Attraction

A handful of studies yields information regarding the attraction process for same-gender relationships. An investigation of personal ads found that homosexuals tend to request sex-typical, as opposed to sex-atypical, traits, with men frequently seeking masculine gay male partners, for example, and women often requesting feminine lesbian partners (Bailey et al. 1997; Phua 2002; Smith and Stillman 2002). Gay men and lesbians who place personals ads also demonstrate patterns of gender differences in language similar to those of heterosexuals (Groom and Pennebaker 2005). Evidence emerges in personals ads of a tendency for working-class and younger lesbians, however, to describe themselves, or the partner they seek, using the terms “butch” and/or “femme” (Weber 1996; Crawley 2001). In their response to mating psychology scales, homosexuals appear to be similar to heterosexuals of their own gender in many of their mating preferences (Bailey et al. 1994). Put another way, several related patterns of mate selection appear among men and women based on gender category membership, regardless of sexual orientation. In addition, similar to findings with heterosexuals, homosexuals emphasize mental, positive personality, and family-oriented characteristics when considering a long-term romantic partner, as opposed to a short-term sexual partner; physical appeal is rated more highly for a potential sex partner (Regan et al. 2001). Finally, according to one of the few survey studies of attraction that includes homosexuals (Howard et al. 1987), U.S. heterosexuals, lesbians, and gay men all rate indicators of expressiveness (e.g., affectionate, compassionate, expresses feelings) as most desirable in an ideal partner. To the extent differences between groups exist, gay men and lesbians display even stronger preferences for expressiveness than do heterosexuals.

Several studies identify basic similarities in general relationship processes and functioning when comparing across gay, lesbian, and heterosexual couples. For instance, the same variables predict relationship quality and stability for gay, lesbian, and heterosexual married couples (Kurdek 2004, 2005). On the other hand, there are some differences between groups. For instance, when compared to married couples, lesbian and gay partners report greater autonomy, fewer barriers to leaving a relationship, and more frequent relationship breakups (Kurdek 1998).

Similar Partner Likes and Dislikes

Prior research finds that individuals sometimes report what appear to be related likes and dislikes in a dating partner or spouse (Felmlee 1995; Pines 1997). In particular, the qualities that initially attract individuals to their spouse or partner can be connected to those that they report as an eventual irritant or a cause of conflict. An example of such a case occurs when people say that they were attracted originally to a partner’s success in the workplace, but now dislike that person’s extreme ambitiousness or tendency to work too much. Presumably the disliked partner attributes of ambition and overworking are closely linked to that of the attractive trait of successfulness. Another instance occurs in relationships in which people are drawn to a partner or spouse’s humorous side, but then they come to dislike their partner’s tendency to joke too much and their avoidance of serious matters. Once again, the admired quality of a loved one, a great sense of humor, closely relates to the irritating characteristics of repeated joking and a lack of seriousness. Such patterns of associated partner likes and dislikes occur in a number of marriages (Pines 2005) as well as among some dating couples (Felmlee et al. 2008).

These relationship patterns, sometimes termed “fatal attractions,” (Felmlee 1995) may occur because the extreme, positive virtues of another (e.g., extremely successful, great sense of humor) serve as a source of romantic attraction and interest. Personal qualities that are extreme, even those that are considered virtues, are particularly prone to have downsides and connected costs, according to arguments dating back to Aristotle (1994/350 B.C.E.). Infatuation may temporarily blind an individual to the negative aspects of an appealing partner attribute, but when infatuation fades, the negative aspects of that attribute become more apparent. Some degree of relationship dissatisfaction or disenchantment ensues when the costs associated with a particular partner quality outweigh its benefits, according to exchange theory.

Yet research to date on this phenomenon has been limited to cross-gender relationships. Here we have data on the qualities that individuals in same-gender relationships report as attractors, as well as the ones they dislike. Another goal of this research, therefore, is to use our data to investigate whether the same, seemingly paradoxical processes of attraction and disaffection can occur in same-gender pairs. Stereotypes imply that equivalent underlying processes do not govern same- and cross-gender relationships (Herek 1991). Yet social exchange theory suggests that any dyad, regardless of gender composition and level of intimacy, remains subject to the equivalent cost and benefit analyses that influence relationship assessments. The specific types of costs and benefits may differ between same-gender and cross-gender couples, as noted above, but the basic relationship assessment processes should be the same. We therefore expect to find evidence among our respondents of similarity between reports of attractive and disliked partner qualities, as documented in prior research with cross-gender romantic dyads.

We investigate this hypothesis in two ways—quantitatively and qualitatively. First, we use Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis to test the argument that people in same-gender relationships can become disenchanted with the same qualities that first attracted them to their partner. The dependent variable in this set of analyses captures the degree to which respondents perceive their partner as having too much, or an excess, of a set of traits. The key, theoretical covariate measures the degree of attraction experienced by the respondent to this same set of traits in his or her partner at the time of initial attraction. We hypothesize that this covariate, the degree of initial attraction to a partner’s trait, will be positively related to the degree to which people report that their partner now exhibits “too much” of that same trait, while controlling for several other factors.

Next, we examine the open-ended data gathered from our survey to see whether there are incidences of similarity between attractive and disliked partner qualities in the written, qualitative reports of our respondents, as documented previously in open-ended data from heterosexuals. The occurrence of such incidents of disenchantment in the open-ended data would further validate our hypothesis as well as illustrate examples of this phenomenon among female couples and male couples.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

In sum, we argue that the basic, underlying attraction processes for those in same-gender relationships resemble those found previously in cross-gender relationships. In particular, we investigate the following research questions:

-

RQ1:

What qualities attract one person to another in same-gender relationships?

-

RQ2:

Are there similarities between liked and disliked partner traits, as suggested by research on disenchantment?

In addition, we will test the following hypotheses. Note that we expect to find evidence that contradicts the first two hypotheses and evidence that supports the 3 rd one. That is, we expect to fail to reject the null hypothesis for H1 and H2 and reject the null hypothesis for H3:

-

H1:

Negative Stereotype Hypothesis: Gays and lesbians are thought to be “hypersexual,” and therefore physical attractors are the most highly rated attractors among those in same-gender relationships.

-

H2:

Gender as Binary Hypothesis: Females and males in same-gender relationships differ substantially in the qualities that attract them to another person, according to the “gender as binary” assumption.

-

H3:

Disenchantment Hypothesis: Attraction to a particular quality in a partner relates positively to the likelihood of later viewing that partner as exhibiting too much, or an excess, of that same quality.

Method

Study Design and Participants

This study employs survey data from 120 individuals in the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) community. Three-quarters (76%) of the respondents were recruited from the attendees of a public LGBT event in a large Northern California city. Data from volunteers were collected at a booth rented by the researchers. To increase the sample size, respondents were also obtained at the LGBT Center of a college campus in Northern California and through a snowball sample. Following briefing and informed consent protocol in which participants were assured confidentiality, participants completed a questionnaire regarding their current or most recent romantic relationship.

The sample consists of 68 females and 52 males. Mean respondent age is 38 years, with a range of 18 to 71 years. Forty-seven percent of participants hold at least a college degree. The sample captures some variation in ethnicity among respondents: 66% identified as Caucasian, 10% as Latino/a, 8% Black/African American, 8% Asian/ Asian American/Pacific Islander, and 6% as “Other.” The length of the relationships in this study varied from less than 1 month to 49 years, with a mean length of 11.5 years. Seventy-five percent of the relationships we consider in this paper were ongoing at the time of the survey. Four individuals in our sample identified as transgender and were not included in the final study because of the small number of cases. There were no significant differences between women and men in any of the background characteristics or in the covariates for the regression analysis (see Table 1). Correlations among the variables used in our regressions are shown in Table 1.

Open-ended Questions

Questionnaires began with open-ended questions regarding individuals’ intimate relationship. Respondents were instructed to think about the romantic relationship in which they were involved, or their most recent relationship, if they were not currently involved with someone. Two open-ended questions were posed: (a) Describe the specific qualities that first attracted you to that individual. (b) What are (were) the specific qualities about that individual that you find least attractive?

Responses to these questions were coded separately by two of the authors. Each case was coded for the presence or absence of similarity between an initially attractive quality and one that was later disliked, that is, whether or not a disliked partner quality represented the same, or an excessive amount, of the originally attractive quality. Such incidents represent cases of “disenchantment,” or “fatal attraction.” Previous research on disenchantment using open-ended data was used to aid in coding (e.g., Felmlee 1995; Pines 2005). For example, based on earlier work, the disliked partner quality of “arrogance” was considered to be an excessive display of the originally appealing quality of “confidence,” whereas “an inability to be serious” represented “too much” humor. Interrater reliability for the coding was .74 (kappa). Discrepancies were settled by the first author.

Closed-ended Questions

Following the open-ended questions, respondents also answered several questions regarding twenty-one personal qualities, using seven-point Likert response scales:

-

1.

“Recall the period when you were initially attracted to your current (or former) partner. To what extent were you attracted to the following qualities in your partner?” (1 = Not At All, 7 = Extremely)

-

2.

“Think of yourself. To what extent do YOU possess the following qualities?” (1 = Not At All; 7 = Extremely)

-

3.

“Think of your current [or former] partner now. To what extent does YOUR PARTNER now exhibit these qualities: (1) too little (not enough; an undersupply), (4) the ideal amount (just the right amount) or (7) too much (more than is ideal; an overabundance)?

The twenty-one characteristics include: adventurous, ambitious, appearance, confident, considerate, dresses well, financially secure, fun, good job, good listener, independent, intelligence, kind, nice body, nice house, outgoing, sense of humor, sexy, successful, supportive, and understanding. Characteristics were derived from mate selection theory and research (Fletcher 2002), the five major personality factors (Farmer et al. 2001), as well as from sets of common attracting qualities, such as physical appearance, identified in previous research (e.g., Felmlee 2001).

We employed exploratory factor analysis, with an orthogonal varimax rotation, to reduce our 21 characteristics to a smaller number of discrete partner qualities. This produced five empirically and conceptually distinct factors: Agreeableness (kind, supportive, considerate, understanding, good listener; α = .8964), Extroversion (fun, sense of humor, outgoing, adventurous; α = .7144), Status (has, or has the potential for, a good job, a nice house, security, success, to dress well; α = .8597), Physical attractiveness (nice body, attractive appearance, sexy; α = .8518), and Motivation (ambitious, confident, independent, intelligent; α = .7453). Factors were constructed by taking respondents’ mean score for all relevant traits in a set.

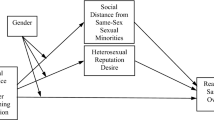

Dependent Variable and Covariates

The dependent variables in our regression analyses measure the degree to which respondents perceive their partner as having too much of a set of key traits. The key covariates in this study address the degree of attraction experienced by the respondent to a particular set of traits in his or her partner at the time of initial attraction. These variables are also factors derived from the 21 qualities previously discussed. We include several other covariates as controls. One set of variables are factors that capture the degree to which the respondent perceives him/herself as possessing a particular set of traits. We use this set of factors to examine the possible tendency of individuals to be more (or less) tolerant of excessive qualities in a partner that they themselves possess in excess. We include four other control variables in the analysis: age (measured in years), respondent’s gender (female vs. male), respondent’s race (white vs. non-white), and respondent’s educational attainment (college graduate vs. non college graduate). We incorporate these controls because these demographic characteristics occasionally relate significantly to the likelihood of disenchantment with an originally attractive partner quality among heterosexuals (e.g., Felmlee et al. 2008). We want to rule out the argument that any of the control measures, rather than our main covariate, initial attraction to a partner quality, accounts for a tendency to experience disenchantment. In addition, we eliminated a measure of relationship length from our analyses because of collinearity problems with age and other variables. We also removed a measure of the status of the relationship — whether or not it was still intact at the time of the survey — because it had no significant effect in the model. There were no significant gender differences in any of the covariate measures (see Table 1).

Results

Research Question 1: What Qualities Attract One Person to Another in Same-gender Relationships?

Quantitative Analyses

First, we investigate patterns of romantic attraction in our sample. We begin by examining mean ratings for the 21 individual attracting qualities. As can be seen in the first column of Table 2, fun, sense of humor, and intelligent are the three qualities rated most highly, on average, by both women and men as characteristics that attracted them to their partner. These qualities are followed closely in mean rating by the following: kind, supportive, and considerate. On the other hand, both sexes rated the potential attracting quality of possessing, or having the potential to possess, a “nice house” the lowest of all the 21 potentially desirable traits. It is the lowest ranked quality for both men and women together (see column 1 of Table 2) as well as for males and females separately (see columns 2 and 3 of Table 2). Other low-ranked traits include: financial security, success, and ambitiousness.

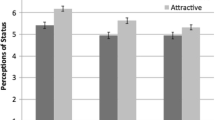

Next we examine the mean ratings for the five composite factors of the 21 qualities in order to create a more complete picture of what draws people to their same-gender romantic partner: Agreeableness, Extroversion, Physically Attractive, Motivated and Status. As can be seen in Table 3, Agreeableness (i.e., kind, supportive, considerate, understanding, good listener) constitutes the most highly rated attracting factor, followed by Extroversion, Physically Attractive, and Motivated. The Status factor (has, or has the potential for, a good job, a nice house, security, success, dress well) rates the lowest.

Hypothesis 1: Gender as Binary: Females and Males Differ Substantially in What Attracts Them to Another

We find that men and women in our sample are much more alike than different in their ratings of the specific, attracting partner characteristics (see the second and third columns of Table 2), evidence that contradicts H1. There are no significant gender differences in the ratings of these attracting qualities, according to a MANOVA (F(21, 88) = 1.13, p = .33). The order of the rankings of individual qualities also is quite similar for both males and females, with few differences. In one minor discrepancy, for instance, males rate intelligence as the most important attracting quality, while females rate it as 3 rd. In addition, the means for the five attraction factors do not differ significantly between women and men, as can be seen in the 2 last columns of Table 3 (F(5, 112) = 1.92, p = .10). Thus, our evidence contradicts H1, and we fail to reject the null hypothesis of no difference between males and females in attraction (H1).

Hypothesis 2: Negative Stereotypes: Attractors in the Category of Physical Attractiveness Will Be the Most Highly Rated

As can be seen in Table 2 (Column 1), physical attractors are not the most prominent attractors for those in male relationships or female relationships. “Sexy” rates 7th among attractors, whereas the next most common physical attractors, “appearance” and “nice body,” rate11th and 12th, respectively, out of 21 items. Our analysis of differences between means among the various attraction factors tells an even more compelling story. The mean score for Agreeableness is significantly higher than that of the third-ranked factor of Physical Attractiveness (p < .05) and higher than that of all the other factors as well (see Table 3). Mean scores for the factor Status are significantly lower than that of all the other attractors (p < .001). In other words, Agreeableness captures a particularly important set of attractive partner characteristics, as compared to that of Physically Attractive, Extroversion Motivated, and Status Seeking. Status seeking qualities are particularly unimportant attractors. Therefore, our evidence contradicts H2, and we fail to reject the null hypothesis.

Qualitative Analyses

Responses to the open-ended question as to what first attracted participants to their partner reflect similar trends in attracting qualities to those obtained in the quantitative analyses and reinforce the salience of the traits deemed most important. Some respondents, for instance, specifically report “kindness,” “intelligence,” “a sense of humor,” and/or a “fun” personality as important initial attractors, and these are the individual traits that received the highest ratings in the closed-ended scales (see Table 2). In addition, many respondents describe characteristics associated with the most important attracting factor, according to the quantitative data, of agreeableness (see Table 3). For example, one woman reports that “I like good humored, loveable, spiritual individuals who have heart and depth. Looks are good too but not the most important.” In another instance, a man emphasizes the caring nature of his partner: “He is quite caring and I was easily able to confide things in him that I had rarely told my strongest friends.” Another woman writes that the following qualities attracted her to her partner: “She made me feel good inside, she made me happy and my heart filled up with love for her.” More generally, a number of men and women characterized their partners’ appealing qualities using adjectives related to the broad factor of agreeableness, such as “sweet”, “compassionate”, and/or “generous.”

Open-ended comments on the part of respondents reflected additional highly rated attractors, such as those related to extroversion and intelligence. In one case, a young man reported that what first attracted him to his partner was that he “was dancing silly at a party,” while a woman, in referring to the beginning stages of her same-gender relationship, said “I was immediately attracted to her… witty, smart-ass demeanor.” Both of these descriptions appear to capture partners who exhibit outgoing, extroverted personalities. Intelligence, another common attracting quality, also received a good deal of attention as an attractor in the open-ended responses: “Intelligence [was] a major factor,” reports one man when describing what drew him initially to his partner.

Only rarely (3% of cases) did any of our participants mention characteristics as attractors that allude to their partner’s success, or potential for success (e.g., “profession,” “cool car.”). Recall that the factor of Success represented the category of attractors that was rated the lowest in the closed-ended data. Here we see that the qualitative data confirm the relative unimportance of Success as an attractor.

Hypothesis 3: Disenchantment Hypothesis: Attraction to a Quality Relates Positively to the Likelihood of Later Viewing That Partner as Exhibiting Too Much of That Same Quality

Quantitative Analyses

We uncover evidence of a tendency to report excessiveness in an originally attractive trait of a partner in our multivariate regression analyses of closed-ended responses (see Table 4). We find that a respondent’s level of attraction to a set of traits in a partner relates significantly and positively to the degree to which that person now views his or her partner as exhibiting “too much” of that same set of qualities, net of controls, findings that provide support for our third hypothesis. For example, the more individuals report being originally attracted to traits of “extroversion” in their partner, the stronger is their tendency to rate that same person as now possessing “too much” extroversion. Likewise, the more intense the initial attraction to “motivation” in a partner, then the more prone respondents are to evaluating that same individual as currently displaying an excessive amount of motivation. This type of result holds true for the regression analyses of each of the five desirable partner factors, while controlling for several variables, including the individuals’ own expression of the same quality, age, gender, race, and level of education. In other words, it appears that an initially intense attraction to a particular type of partner quality often is associated with a subsequently negative evaluation of that same quality. That is, the partner tends to be now seen as having a more than ideal amount of the originally desirable characteristic.

The pattern of significant results for our key measure, initial attraction to a partner’s quality, is particularly robust. For instance, we find additional support for our findings when we replicate our analyses using each of the 21 individual traits as the dependent measures, rather than the five composite factors (not shown here). We employ ordered, logistic regression analysis with the ordinal responses to each of the 21 individual attracting traits as the dependent measures (1–7 Likert response scales). We apply the false discover rate criterion when determining statistical significance, in order to control for problems with multiple hypothesis testing (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). With only a couple of exceptions, we find that the reported initial level of attraction to a particular partner quality relates positively, and significantly, to the likelihood that individuals report that their partner now exhibits that same, originally appealing quality, to an excessive degree. Moreover, we found the equivalent associations when we employ ordinary least squares or multinomial modeling rather than OLS. Note that ordinal regression is not a viable analytic technique when one of our five attracting factors is the dependent variable (see Table 4), because these factors have as many as 35 possible outcome values. Furthermore, we analyzed our models separately for males and females and found the same pattern of positive, statistical significance for our hypothesized predictor variable, level of initial attraction.

The respondents’ own expression of a quality had no statistically significant association with the likelihood to rate their partner as having too much (or too little) of a particular quality. This suggests that people are neither more nor less tolerant of a quality they see themselves as having in excess. Similar to findings with cross-gender couples (e.g., Felmlee et al. 2008), the demographic measures of age, race, and education displayed only occasional significant effects in the model. Finally, we find no evidence of multicollinearity in our models, according to the Variance Inflation Factor.

Research Question 3: Similarities Between Liked and Disliked Partner Traits

Open-ended Responses

Similar to studies of heterosexuals (e.g., Felmlee 1995; Pines 2005), we also uncover a number of cases in which there are similarities between liked and disliked partner qualities in the qualitative data. Here we compare the open-ended responses of the participants to the question regarding what attracted them to their partner with those to the question asking them what they now “least like” about that same person. These disenchanting attractions occur among both males and females in the qualitative data, as seen in Table 5.

In one illustration, a woman reports that the qualities that originally attracted her to her long-term partner, to whom she considers herself married, were that this woman was “spontaneous [and] funny.” On the other hand, the characteristics that she finds least attractive about her now include that she is: “crass and inappropriately loud in social situations (embarrassing).” In other words, the otherwise desirable qualities of spontaneity and humor in her mate have a negative side, such as that of embarrassing behavior. This respondent appears to experience some degree of disenchantment with the qualities that originally drew her to her partner, and this occurs in spite of the fact that she is highly committed to the relationship.

In another example, a man reports that the following traits first interested him in his gay partner of 9 years: “…quiet, a bit shy and nice hairy legs.” He dislikes, however, that this person is: “Too much of a ‘lone wolf,’ secretive, seemed ashamed to be seen in public with me…” In other words, this man who was attractive in part because he was quiet and shy in the first place, is now viewed as “secretive,” too much of a loner, and too shy in public. Here again it seems that the originally attractive qualities of a partner eventually constitute a source of relationship distress.

In another case, the following qualities drew a woman to her lesbian partner of approximately 11 months: she “fed me all the time,” “let me fix things for her,” and was willing to become involved. Nevertheless, she complained that her partner had a “low self esteem engine” and that “[s]he was too submissive and would let anyone manipulate her.” The main complaints about her former partner (i.e., overly submissive and low self esteem) appear closely related to what attracted her in the first place, that is, the woman’s apparent extreme eagerness to please.

Discussion

We began this paper interested in examining attraction processes in same-gender relationships. We find that agreeableness, extroversion, and intelligence represent prominent bases of attraction, according to our participants. The top five most highly rated attracting qualities include: fun, sense of humor, intelligence, kindness, and supportiveness. The lowest rated attractors, on the other hand, represent traits associated with material success (e.g., success, financial security). We also document evidence of seemingly paradoxical attractions in our sample, both in the qualitative and quantitative data. In the quantitative data, the stronger the initial attraction is to a particular characteristic of a partner, the more likely it is that an individual comes to believe that his or her partner now possesses “too much” of that same characteristic. Furthermore, a number of individuals describe in their open-ended responses disliked qualities in their partner that are closely linked to those that initially attracted them to that same person.

Women and men display attraction processes that are much more alike than different in our sample, findings that contradict the thesis that gender is binary when it comes to romantic attraction among those in gay and lesbian relationships. Identical primary factors of attracting qualities emerge in the analyses (e.g., extroversion, intelligence and agreeableness), and there are no significant gender differences in the means for either the factors, nor in the 21 individual, attracting qualities. Both males and females often report similarities between what they view as positive and negative qualities in their partner as well, according to both the qualitative and quantitative analyses.

Our findings echo those of studies on cross-gender relationships and marriages. Men and women report that they are most strongly attracted to some of the same general, personality characteristics in a partner. For example, the attractors of extroversion, agreeableness, and intelligence documented here in same-gender relationships are the same factors that have been found to be important bases for romantic attraction in cross-gender relationships (e.g., Fletcher 2002). This is not to say that physical attractiveness plays no role in attraction here. Characteristics related to physical attractiveness, such as sexiness and physical appearance also influence the romantic attraction process, both in this study and in previous studies of heterosexuals (e.g., Duck 1988; Feingold 1991). Nevertheless, neither people in same-gender nor those in cross-gender relationships tend to rate characteristics related to physical qualities as the most important attractors in their relationships.

As suggested by social exchange theory, the women and men in our sample appear to be sensitive to the rewards and costs associated with a particular relationship. They report being drawn to various positive and highly rewarding qualities in their partner at the onset of their relationship, such as expressiveness. At the same time, they often are acutely aware of the problematic and costly side of involvement with that same person. The attraction process of same-gender relationships, as with cross-gender relationships, reflects something of a cost-benefit analysis, as documented in some prior research (see review by Peplau and Fingerhut 2007). Exchange principles appear to operate in some similar ways for both types of couples.

Our results dispute several common stereotypes regarding men and women in same-gender pairings. In particular we find no evidence that they are prominently attracted to gender atypical qualities in a partner. Both women and men in our sample tend to be drawn to agreeableness in a loved one (e.g., kindness, supportiveness), a personality quality that can be considered traditionally feminine. Intelligence, traditionally a hegemonic masculine quality, also appears as an important attractor; it is the top single attractor for males in our sample. Traits related to extroversion (e.g., fun and sense of humor) remain additional, highly ranked attractors, and these represent characteristics not typically included in either gender stereotype.

The findings highlight the problem of conflating performance of gender with sexual orientation/identity. Males in our sample are not attracted primarily to effeminate partners, nor do women consistently seek out other women who display qualities traditionally constructed as masculine. Rather both men and women in same-gender relationships look for partners with the conventional, appealing qualities of agreeableness and extroversion.

Our data speak to an additional misleading assumption, drawn from simplified generalizations regarding heteronormative relationships, that same-gender partnerships will typically develop two complementary gender roles. There is little evidence that the individuals in our sample are attempting to reconstruct a purportedly typical, heterosexual relationship model in which one partner is supposed to be primarily masculine in gender role orientation while the other is expected to be feminine. Same-gender couples do not appear to routinely adhere to a strict, dual role, archetype of an intimate relationship. Instead individuals of both sexes tend to seek out partners who display both certain traditional feminine qualities, such as kindness, as well as some typical masculine characteristics, such as intelligence. At the same time, there exists variance along these lines, with some people of either gender expressing a penchant for so-called feminine partner characteristics and others an inclination for those that are masculine. We see here a fluidity of gender performance expectations, preferences, and couplings that is not captured fully by common, homosexual stereotypes.

Our findings also challenge the assumption that those in same-gender relationships and men in particular are “hypersexual,” or too obsessed with sex. Personality characteristics of a partner, rather than physical qualities, emerged as the highest attractors in this sample for both women and men. This is not to say that physical attractiveness played no role in the same-gender attraction process. “Sexiness” in a partner was ranked on average seventh in importance, out of the 21 possible attracting characteristics, whereas “appearance” and “nice body” were rated 11th and 12th, respectively. In other words, although physical and sexual characteristics emerged as moderately relevant attractors, they by no means dominated the process by which individuals became interested in their same-gender partner. Moreover, our results contradict the stereotype that these men and women fail to value, and are unable to form lasting bonds. Our study includes a number of lengthy, highly committed relationships, and the average relationship length was substantial — 11.5 years.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, our sample is small and relatively select. Participants at an LGBT Pride event are apt to be more active in the LGBT community, and may be more outgoing, outspoken, and less reclusive than some. For such participants, certain attractors may be of particular import, such as the fact that a potential partner is “out,” that is, she or he is open about matters of sexual orientation, and capable of celebrating at a public event. Individuals who participate in LGBT Pride also may have more opportunities to form alternative relationships than do those not involved in such social gatherings. Second, it would be useful to examine the attraction process as individuals progress from the very start of relationships through the mature relationship stage exhibited by many in our sample, a research design that was beyond the scope of the current project. Such a design would provide an opportunity to document the processes of attraction as they unfold in the course of a relationship; to see when certain qualities are first identified as important traits of attraction, and if and when they are viewed as excessive. Furthermore, other minority groups not examined here also must navigate the terrain of the dominant white, middle class, and heterosexual notions of intimate bonds. The intersection of racial and sexual repression potentially creates unique social conditions that affect the romantic relationships of people of color in the LGBT community. For example, homophobic and racial stereotyping constrains the gender options for both gay and African-American males by depicting both as hypersexual. The lack of racial diversity in our sample does not allow us to explore these intriguing connections, however, and this remains an important task for future research.

In sum, our findings speak to the belief held by some Americans that same-gender relationships are fundamentally different from “normal” heterosexual relationships. The attraction process in same-gender relationships appears comparable in many ways to that documented among heterosexual ties. Adults in same-gender pairs appear to be prone to the similar, complex, and sometimes contradictory, relationship dynamics found in cross-gender couples.

Note that we do not conclude that same- and cross-gender relationships are identical in all respects, with the exception of sexuality. There are a host of experiences common to people in the LGBT community that might complicate their intimate dyads. Individuals from the community interact within a culture defined by structural and interpersonal homophobia and heterosexism, and experience stress and mental health issues related to their minority status (Meyer 1995). The social experiences of homophobia and heterosexism that confront the LGBT community, and the host of structural impediments that they face, undoubtedly influence their intimate bonds. Yet we find extensive evidence that the basic attraction processes in same- and cross-gender relationships hold a number of common threads. Finally, our results contradict many of the typical stereotypes regarding men and women in same-gender relationships that predominate in public discourse.

References

Alex-Assensoh, Y. M. (2005). Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. [Review of the book Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism]. Politics and Gender, 1, 361–363.

Aristotle. (1994). Nicomachean ethics. (W. C. Ross, Trans.). In D.C. Stevenson (Ed.), The internet classics archives. (Original work published 350 B.C.E.). Retrieved from http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.html

Aron, A., Dutton, D. G., Aron, E. N., & Iverson, A. (1989). Experiences of falling in love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 6, 243–257.

Bailey, J. M., Gaulin, S., Agyei, Y., & Gladue, B. A. (1994). Effects of gender and sexual orientation on evolutionarily relevant aspects of human mating psychology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 1081–1093.

Bailey, J. M., Kim, P. Y., Hills, A., & Linsenmeier, J. A. W. (1997). Butch, femme, or straight acting? Partner preferences of gay men and lesbians. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 960–973.

Bem, S. L. (1993). The lenses of gender: transforming the debate on sexual inequality. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 57, 289–300.

Bernstein, M. (1997). Celebration and suppression: The strategic uses of identity by the lesbian and gay movement. American Journal of Sociology, 103, 531–565.

Berscheid, E., & Hatfield, E. (1969). Interpersonal attraction. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Berscheid, E., & Reis, H. T. (1998). Attraction and close relationships. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology (4th ed., pp. 193–281). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Butler, J. (1999). Gender trouble: feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge.

Comstock, G. D. (1991). Violence against lesbians and gay men. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cook, K. S., & Emerson, R. M. (1987). Social exchange theory. Beverly Hills: SAGE Publications.

Crawley, S. L. (2001). Are butch and fem working-class and antifeminist? Gender & Society, 15, 175–196.

Duck, S. (1988). Handbook of personal relationships: theory, research, and interventions. Chichester [England]; New York: Wiley.

Elections recommendations listed. (1992, November 2). The Oregonian, (Portland, OR) 4th ed., D12. Retrieved from NewsBank on-line database (Access World News): http://infoweb.newsbank.com

Farmer, R. F., Jarvis, L. L., Berent, M. K., & Corbett, A. (2001). Contributions to global self-esteem: The role of importance attached to self-concepts associated with the five-factor model. Journal of Research in Personality, 35, 483–499.

Feingold, A. (1991). Sex Differences in the effects of similarity and physical attractiveness on opposite-sex attraction. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 12, 357–367.

Felmlee, D. H. (1995). Fatal attractions: Affection and disaffection in intimate relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12, 295–311.

Felmlee, D. H. (1998). Be careful what you wish for...": A quantitative and qualitative investigation of "fatal attractions". Personal Relationships, 5, 235–253.

Felmlee, D. H. (2001). From appealing to appalling: Disenchantment with a romantic partner. Sociological Perspectives, 44, 263–280.

Felmlee, D. H., Flynn, H. K., & Bahr, P. R. (2008). Too much of a good thing: Fatal attraction in intimate relationships. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 36, 3–14.

Fletcher, G. J. O. (2002). The new science of intimate relationships. Malden: Blackwell.

Geiger, W., Harwood, J., & Hummert, M. L. (2006). College students' multiple stereotypes of lesbians: A cognitive perspective. Journal of Homosexuality, 51, 165–182.

Glick, P., Gangl, C., Gibb, S., Klumpner, S., & Weinberg, E. (2007). Defensive reactions to masculinity threat: More negative affect toward effeminate (but not masculine) gay men. Sex Roles, 57, 55–59.

Golebiowska, E. A. (2001). Group stereotypes and political evaluation. American Politics Research, 29, 535–565.

Golebiowska, E. A. (2002). Political implications of group stereotypes: Campaign experiences of openly gay political candidates. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 590–607.

Golebiowska, E. A. (2003). When to tell?: Disclosure of concealable group membership, stereotypes, and political evaluation. Political Behavior, 25, 313–337.

Graziano, W. G., & Bruce, J. W. (2008). Attraction and the initiation of relationships: A review of the empirical literature. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of Relationship Initiation (pp. 269–295). New York: Psychology Press.

Groom, C. J., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2005). The language of love: Sex, sexual orientation, and language use in online personal advertisements. Sex Roles, 52, 447–461.

Gurwitz, S. B., & Marcus, M. (1978). Effects of anticipated interaction, sex, and homosexual stereotypes on first impressions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 8, 47–56.

Haddock, G., Zanna, M. P., & Esses, V. M. (1993). Assessing the structure of prejudicial attitudes: The case of attitudes toward homosexuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1105–1118.

Heaven, P. C. L., & Oxman, L. N. (1999). Human values, conservatism, and stereotypes of homosexuals. Personality & Individual Differences, 27, 109–118.

Herek, G. M. (1991). Stigma, prejudice, and violence against lesbians and gay men. In J. C. Gonsiorek & J. D. Weinrich (Eds.), Homosexuality: Research implications for public policy (pp. 60–80). Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Herek, G. M. (2004). Beyond "homophobia": Thinking about sexual stigma and prejudice in the twenty-first century. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 1(2), 6–24.

Herek, G. M. (2007). Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: Theory and practice. Journal of Social Issues, 63, 905–925.

Herek, G. (2008, November 25). The psychological harm of anti-gay ballot campaigns. Retrieved from http://www.beyondhomophobia.com/blog/2008/11/25/anti-gay-ballot-campaigns-cause-psychological-harm/

Herek, G. M., & Berrill, K. T. (1990). Violence against lesbians and gay men: issues for research, practice, and policy. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Hicks, G. R., & Lee, T-t. (2006). Public attitudes toward gays and lesbians: Trends and predictors. Journal of Homosexuality, 51, 57–77.

Howard, J. A., Blumstein, P., & Schwartz, P. (1987). Social or evolutionary theories: some observations on preferences in human mate selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 194–200.

Kelley, H. H., & Thibaut, J. W. (1978). Interpersonal relations: a theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley.

Kurdek, L. A. (1998). Relationship outcomes and their predictors: Longitudinal evidence from heterosexual married, gay cohabiting, and lesbian cohabiting couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 553–568.

Kurdek, L. A. (2004). Are gay and lesbian cohabiting couples really different from heterosexual married couples? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66, 880–900.

Kurdek, L. A. (2005). What do we know about gay and lesbian couples? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 251–254.

LaMar, L., & Kite, M. (1998). Sex differences in attitudes toward gay men and lesbians: A multidimensional perspective. Journal of Sex Research, 35, 189–196.

Levitt, E. E., & Klassen, A. D. (1974). Public attitudes toward homosexuality: Part of 1970 National Survey by Institute for Sex Research. Journal of Homosexuality, 1, 29–43.

Lorber, J. (1996). Beyond the binaries: Depolarizing the categories of sex, sexuality, and gender. Sociological Inquiry, 66, 143–159.

Madon, S. (1997). What do people believe about gay males? A study of stereotype content and strength. Sex Roles, 37, 663–685.

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 38–56.

Molm, L. D. (1997). Risk and power use: Constraints on the use of coercion in exchange. American Sociological Review, 62, 113–133.

Orbuch, T. L., & Sprecher, S. (2003). Attraction and interpersonal relationships. In J. Delamater (Ed.), Handbook of Social Psychology (1st ed., pp. 389–410). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Patterson, C. J. (1995a). Gay and lesbian parenthood. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of Parenting: Status and Social Conditions of Parenting (Vol. 3, pp. 255–274). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Patterson, C. J. (1995b). Lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children. In A. R. D'Augelli & C. J. Patterson (Eds.), Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identities Over the Lifespan (pp. 262–290). New York: Oxford University Press.

Patterson, C. J. (2000). Family relationships of lesbians and gay men. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1052–1069.

Peplau, L. A. (1991). Lesbian and gay relationships. In J. C. Gonsiorek & J. D. Weinrich (Eds.), Homosexuality: Research implications for public policy (pp. 177–196). Newbury Park: Sage.

Peplau, L. A. (1993). Lesbian and gay relationships. In L. Garnets & D. C. Kimmel (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay male experiences (pp. 395–419). New York: Columbia University Press.

Peplau, L. A., & Spalding, L. R. (2000). The close relationships of lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. In C. A. Henrick & H. S. Singer (Eds.), Close Relationships: A Sourcebook (pp. 111–123). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Peplau, L. A., & Fingerhut, A. W. (2007). The close relationships of lesbians and gay men. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 405–424.

Pines, A. M. (1997). Fatal attractions or wise unconscious choices: The relationship between causes for entering and breaking intimate relationships. Personal Relationship Issues, 4, 1–6.

Pines, A. M. (2005). Falling in love: why we choose the lovers we choose (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Phua, V. C. (2002). Sex and sexuality in men’s personal advertisements. Men and Masculinities., 5, 178–191.

Plummer, D. C. (2001). The quest for modern manhood: masculine stereotypes, peer culture and the social significance of homophobia. Journal of Adolescence, 24, 15–23.

Regan, P. C., Medina, R., & Joshi, A. (2001). Partner preferences among homosexual men and women: What is desirable in a sex partner is not necessarily desirable in a romantic partner. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 29, 625–633.

Sandroussi, J., & Thompson, S. (1995). Out of the blue: A police survey of violence and harassment against gay men and lesbian. Sydney: New South Wales Police Service.

Sartore, M. L., & Cunningham, G. B. (2009). Gender, Sexual Prejudice and Sport Participation: Implications for Sexual Minorities. Sex Roles, 60, 100–113.

Simon, A. (1998). The relationship between stereotypes of and attitudes toward lesbians and gays. In G. M. Herek (Ed.), Stigma and Sexual Orientation: Understanding Prejudice Against Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals (Vol. 4, pp. 62–81). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Smith, C. A., & Stillman, S. (2002). Butch/Femme in the personal advertisements of lesbians. In S. Rose (Ed.), Lesbian love and relationships (pp. 45–52). New York: Harrington Park Press.

Sprecher, S., & Felmlee, D. (2008). Insider perspectives on attraction. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of Relationship Initiation (pp. 297–313). New York: Psychology Press.

Sprecher, S., Aron, A., Hatfield, E., Cortese, A., Potapova, E., & Levitskaya, A. (1994). Love: American style, Russian style, and Japanese style. Personal Relationships, 1, 349–369.

Stotzer, R. L. (2009). Straight allies: Supportive attitudes toward lesbians, gay, men, and bisexuals in a college sample. Sex Roles, 60, 67–80.

Taywaditep, K. J. (2001). Marginalization among the marginalized: Gay men's anti-effeminacy attitudes. Journal of Homosexuality, 42, 1–28.

Thibault, J. W., & Kelley, H. H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. New York: Wiley.

Weber, J. C. (1996). Social class as a correlate of gender identity among lesbian women. Sex Roles, 35, 271–280.

Wilkinson, W. W. (2008). Threatening the patriarchy: Testing an explanatory paradigm of anti-lesbian attitudes. Sex Roles, 59, 512–520.

Acknowledgements

The authors express appreciation to Greg Herek, Orit Avishai, and Scott Gartner for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this work. Partial funding for this research was provided by Grant BCS-05-27766 from the National Science Foundation. The conclusions remain those of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Felmlee, D., Orzechowicz, D. & Fortes, C. Fairy Tales: Attraction and Stereotypes in Same-Gender Relationships. Sex Roles 62, 226–240 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9701-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9701-x