Abstract

This study examines whether personal net worth affects new venture creation and performance. Prior research on wealth and entrepreneurial entry has relied on data providing only a snapshot of the transition into self-employment. The present study draws on a sample of US nascent entrepreneurs actively attempting to start new ventures. Controlling for a number of covariates and the endogenous accumulation of wealth, we find strong evidence of higher dropout rates among low-wealth and moderately wealthy nascent entrepreneurs. However, wealth appears to have no effect on venture creation for those managing to remain in gestation. This suggests liquidity constraints theory applies more toward entrepreneurial disengagement than entrepreneurial entry. Furthermore, the suggestion that the wealthy are able to aggressively grow their ventures is only partially supported by the data when we include a set of covariates correlated with wealth. Integrating these findings, we conclude that entrepreneurial success is concentrated at the top of the wealth distribution, despite notable evidence of capability for those at the lower end of the wealth distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As of the first interview in the PSED II, each venture had been at risk of termination for a period of time, resulting in left truncation—that is, the sample contains only firms that survived the period between first activity and the first interview, and strong emerging organizations may be overrepresented (Yang and Aldrich 2012).

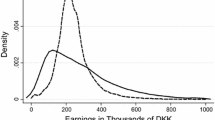

Two features of the graph are worth noting. First, the horizontal scale has been limited to −$100,000 and $1,000,000 so that we can focus on the data’s centrality—the top 8 % and lower 1 % both extend far beyond those limits and dwarf the remainder of the graph. Second, six steep vertical climbs in the (blue) empirical distribution function for the PSED II occur due to those few observations where a unique value for net worth was withheld by the respondent so that we had to impute net worth as the midpoint of the range provided by the respondent.

If one envisions that starting any business requires a minimum amount of investment that is beyond the means of low-wealth individuals, then this can be recast as a −100 % rate of return on an investment beneath that threshold.

The Variance Inflation Factor for each variable is less than 10, with a mean VIF of around 1.14 for each model. We are therefore confident our regression models do not suffer from multicollinearity.

This should reveal any hidden underlying nonlinear relationship, but nothing noteworthy emerges (and hence the results have been suppressed from our plots for clarity).

The loess method uses weighted least squares to fit the regression for each wealth percentile “section” overlaying the regression, weighting data points with a decreasing function of their distance from the wealth level being plotted (Garson 2012). Nonparametric estimation of a nonlinear function is appropriate here given our preliminary observations of the nonlinear effects of wealth on nascent entrepreneur outcomes, at the individual and firm level. These effects mirror those found in structural inequality at the societal level (Piketty 2014).

However, because this approach makes the fewest assumptions on functional form, it is most susceptible to noise in the available sample of modest size.

We also conducted semi-parametric and nonparametric tests to gauge the robustness of our results, given the amount of structure that we impose on the data. To facilitate interpretation of the Figures, the cubic splines, knots, and loess smoothers from these tests were removed. Additionally, the horizontal scales on each Figure are limited to range from −$100,000 to $1,000,000 so that we can focus on the data’s centrality—the top 8 % and bottom 2 % of nascent entrepreneurs in the wealth distribution extend far beyond those limits and dwarf the remainder of the Figure. The actual data points have been suppressed from the plots because they all fall along the horizontal lines at 0 and 1.

References

Acs, Z. (2008). Foundations of high impact entrepreneurship. Breda: Now Publishers Inc. doi:10.1561/0300000025.

Acs, Z., & Armington, C. (2004). Employment growth and entrepreneurial activity in cities. Regional Studies, 38(8), 911–927. doi:10.1080/0034340042000280938.

Acs, Z., & Audretsch, D. B. (1988). Innovation in large and small firms: An empirical analysis. The American Economic Review,. doi:10.1016/0165-1765(87)90211-4.

Aghion, P., & Bolton, P. (1997). A theory of trickle-down growth and development. The Review of Economic Studies, 64(2), 151–172. doi:10.2307/2971707.

Banerjee, A. V., & Newman, A. F. (1993). Occupational choice and the process of development. Journal of Political Economy,. doi:10.1086/261876.

Bates, T. (1990). Entrepreneur human capital inputs and small business longevity. Review of Economics and Statistics, 72(4), 551–559. doi:10.2307/2109594.

Birch, D. L. (2000). The job generation process. In D. J. Storey (Ed.), Small business: Critical perspectives on business and management (Vol. 2, pp. 431–465). London and New York: Routledge.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. J. (1990). What makes an entrepreneur? Evidence on inheritance and capital constraints. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.1086/209881.

Cagetti, M., & De Nardi, M. (2006). Entrepreneurship, frictions, and wealth. Journal of Political Economy, 114(5), 835–870. doi:10.1086/508032.

Cardon, M. S., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 511–532. doi:10.5465/AMR.2009.40633190.

Carter, S. (2011). The rewards of entrepreneurship: Exploring the incomes, wealth, and economic well-being of entrepreneurial households. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 39–55. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00422.x.

Cassar, G. (2004). The financing of business startups. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 261–283. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00029-6.

Cassar, G., & Friedman, H. (2009). Does self-efficacy affect entrepreneurial investment? Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 3(3), 241–260. doi:10.1002/sej.73.

Davidsson, P. (2004). Researching entrepreneurship (International studies in entrepreneurship). Boston, MA: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-26692-3.

Davidsson, P., & Gordon, S. R. (2012). Panel studies of new venture creation: A methods-focused review and suggestions for future research. Small Business Economics, 39(4), 853–876. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9325-8.

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6.

De Meza, D., & Southey, C. (1996). The borrower’s curse: Optimism, finance and entrepreneurship. The Economic Journal, 106(435), 375–386. doi:10.2307/2235253.

Evans, D. S., & Jovanovic, B. (1989). An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. The Journal of Political Economy,. doi:10.1086/261629.

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1989). Some empirical aspects of entrepreneurship. The American Economic Review, 79(3), 519–535.

Fairlie, R. W. (1999). The absence of the African-American owned business: An analysis of the dynamics of self-employment. Journal of Labor Economics, 17(1), 80–108. doi:10.1086/209914.

Fairlie, R. W., & Krashinsky, H. A. (2012). Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship revisited. Review of Income and Wealth, 58(2), 279–306. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4991.2011.00491.x.

Fairlie, R. W., & Robb, A. M. (2008). Race and entrepreneurial success: Black-, Asian-, and White-owned businesses in the United States. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Fairlie, R. W., & Robb, A. M. (2009). Gender differences in business performance: Evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey. Small Business Economics, 33(4), 375–395. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9207-5.

Florin, J., Lubatkin, M., & Schulze, W. (2003). A social capital model of high-growth ventures. Academy of Management Journal, 46(3), 374–384. doi:10.2307/30040630.

Freel, M. S. (2007). Are small innovators credit rationed? Small Business Economics, 28(1), 23–35. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-6058-6.

Garson, G. D. (2012). Multiple regression (statistical associates blue book series). Asheboro, NC: Statistical Associates Publishers.

Gartner, W. B., Frid, C. J., & Alexander, J. C. (2012). Financing the emerging firm. Small Business Economics, 39(3), 745–761. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9359-y.

Gatewood, E. J., Shaver, K. G., Powers, J. B., & Gartner, W. B. (2002). Entrepreneurial expectancy, task effort, and performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 187–206. doi:10.1111/1540-8520.00011.

Gentry, W. M., & Hubbard, R. G. (2004). Entrepreneurship and household saving. Advances in Economic Analysis and Policy,. doi:10.2202/1538-0637.1053.

Henley, A. (2005). Job creation by the self-employed: The roles of entrepreneurial and financial capital. Small Business Economics, 25(2), 175–196. doi:10.1007/s11187-004-6480-1.

Holtz-Eakin, D., Joulfaian, D., & Rosen, H. S. (1993). Entrepreneurial decisions and liquidity constraints (No. w4526). National Bureau of Economic Research,. doi:10.2307/2555834.

Hurst, E., & Lusardi, A. (2004). Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Political Economy, 112(2), 319–347. doi:10.1086/381478.

Kim, P. H., Aldrich, H. E., & Keister, L. A. (2006). Access (not) denied: The impact of financial, human, and cultural capital on entrepreneurial entryin the United States. Small Business Economics, 27(1), 5–22. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-0007-x.

Landes, D. S., Mokyr, J., & Baumol, W. J. (Eds.). (2012). The invention of enterprise: Entrepreneurship from ancient Mesopotamia to modern times. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Liao, J., & Gartner, W. B. (2006). The effects of pre-venture plan timing and perceived environmental uncertainty on the persistence of emerging firms. Small Business Economics, 27, 23–40. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-0020-0.

Liao, J., & Welsch, H. (2005). Roles of social capital in venture creation: Key dimensions and research implications*. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(4), 345–362. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2005.00141.x.

Lindh, T., & Ohlsson, H. (1996). Self-employment and windfall gains: Evidence from the Swedish lottery. The Economic Journal,. doi:10.2307/2235198.

Lofstrom, M., Bates, T., & Parker, S. C. (2014). Why are some people more likely to become small-businesses owners than others: Entrepreneurship entry and industry-specific barriers. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(2), 232–251. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.01.004.

Parker, S. C. (2003). Asymmetric information, occupational choice and government policy*. The Economic Journal, 113(490), 861–882. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.t01-1-00157.

Parker, S. C. (2009). The economics of entrepreneurship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511817441.

Parker, S. C., & Belghitar, Y. (2006). What happens to nascent entrepreneurs? An econometric analysis of the PSED. Small Business Economics, 27(1), 81–101. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-9003-4.

Petrova, K. (2012). Part-time entrepreneurship and financial constraints: Evidence from the panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 473–493. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9310-7.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/9780674369542.

Quadrini, V. (1999). The importance of entrepreneurship for wealth concentration and mobility. Review of Income and Wealth, 45(1), 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4991.1999.tb00309.x.

Quadrini, V. (2000). Entrepreneurship, saving, and social mobility. Review of Economic Dynamics, 3(1), 1–40. doi:10.1006/redy.1999.0077.

Rees, H., & Shah, A. (1986). An empirical analysis of self-employment in the UK. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 1(1), 95–108. doi:10.1002/jae.3950010107.

Reynolds, P. D. (2000). National panel study of U.S. business start-ups: Background and methodology. In J. A. Katz (Ed.), Advances in entrepreneurship, firm emergence and growth (pp. 153–227). Stamford, CT: JAI Press.

Reynolds, P. D., & Curtin, R. T. (2007). Panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics program rationale and description. Retrieved December 10, from http://www.psed.isr.umich.edu/psed/background

Reynolds, P. D., & Curtin, R. T. (2008). Business creation in the United States: Panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics II initial assessment. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 4(3), 155–307. doi:10.1561/0300000022.

Reynolds, P. D., & Curtin, R. T. (Eds.). (2009). New firm creation in the United States: Initial explorations with the PSED II data set. New York: Springer.

Reynolds, P. D., & White, S. B. (1997). The entrepreneurial process: Economic growth, men, women, and minorities. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Robb, A. M., & Watson, J. (2012). Gender differences in firm performance: Evidence from new ventures in the United States. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(5), 544–558. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.10.002.

Shaver, K. G., Davis, A. E., & Kindy, M. S. (2015). Approaching the PSED: Some assembly required. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 22(1), 99–115.

Steffens, P., Terjesen, S., & Davidsson, P. (2012). Birds of a feather get lost together: New venture team composition and performance. Small Business Economics, 39(3), 727–743. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9358-z.

Stiglitz, J. E., & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. The American Economic Review, 71(3), 393–410.

Van Praag, C. M., & Versloot, P. H. (2007). What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small Business Economics, 29(4), 351–382. doi:10.1007/s11187-007-9074-x.

Wiens, J., & Jackson, C. (2015). The importance of young firms for economic growth. Entrepreneurship policy digest. Kansas City: Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

Wolff, E. N. (2014). Household wealth trends in the United States, 1983–2010. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 30(1), 21–43. doi:10.1093/oxrep/gru001.

Xu, B. (1998). A reestimation of the Evans–Jovanovic entrepreneurial choice model. Economics Letters, 58(1), 91–95. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(97)00255-3.

Yang, T., & Aldrich, H. E. (2012). Out of sight but not out of mind: Why failure to account for left truncation biases research on failure rates. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(4), 477–492. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.01.001.

Zissimopoulos, J., Karoly, L., & Gu, Q. (2009). Liquidity constraints, household wealth and self-employment: The case of older workers. RAND working paper series. Retrieved December 10, from doi:10.2139/ssrn.1533502.

Zumbrun, J. (2014). How to save like the rich and the upper middle class (hint: it’s not with your house). The Wall Street Journal: Real Time Economics Blog. Retrieved from http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2014/12/26/how-to-save-like-the-rich-and-the-upper-middle-class-hint-its-not-with-your-house/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frid, C.J., Wyman, D.M. & Coffey, B. Effects of wealth inequality on entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 47, 895–920 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9742-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9742-9

Keywords

- Wealth inequality

- Entrepreneurial entry

- Nascent entrepreneur

- New venture performance

- Liquidity constraints