Abstract

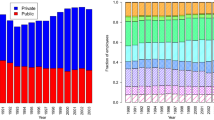

Empirical measures of firm and employment dynamics based on administrative datasets are biased due to missing links in the longitudinal observation of firms. This paper presents a systematic overview of the problems and evaluates two prevailing solutions. We quantify the biases in a set of widely used empirical measures and show which estimates are most sensitive to missing linkages. The biases are found to be especially large in the size distribution of entrants and exits, in firm-level growth estimates for medium and large firms, and in job reallocation measures. We show that an employee-flow linkage method is more effective in reducing bias than a traditional link method often used by statistical agencies. A consistent approach is developed for imputing firm-level growth measures of linked firms. The analysis is carried out using a longitudinal dataset for Belgium and discussed from an international perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Abowd et al. (1999) present a linkage method for France, and Bycroft (2003) for New Zealand; Clayton and Spletzer (2009) describe the longitudinal linkage method applied by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. In Europe, linkage methods adopted by national statistical agencies have led to general Eurostat-OECD recommendations on firm record linking (Eurostat-OECD 2007).

One of the first institutes to implement an employee-flow method has been Statistics Canada (Baldwin et al. 1992), where it is still used for the construction of the National Accounts Longitudinal Microdata File (Dixon and Rollin 2012). Employee-flow methods are also used for the construction of longitudinal employer databases in Denmark (Albaek and Sorensen 1998), Finland (Korkeamäki and Kyyrä 2000), Sweden (Persson 2004), Italy (Contini et al. 2007), Belgium (Geurts et al. 2009), and Germany (Hethey and Schmieder 2013).

Linked employer–employee data have further been used to analyze a wide variety of labor market issues. For a comprehensive overview, see Abowd and Kramarz (1999).

The methods have been developed for the construction of the DynaM longitudinal employer database. The database is designed to track changes in employment at both the macro and the firm levels and to produce annual series of gross job gains and losses statistics in Belgium. See www.dynam-belgium.org.

The unit of the ‘firm’ or more specifically the ‘employer-enterprise’ in the Belgian business register complies with the EU Regulation (EC) No 177/2008 for the harmonization of the national business registers for statistical purposes. It corresponds to ‘the smallest combination of legal units that is an organizational unit producing goods or services, which benefits from a certain degree of autonomy in decision-making, especially for the allocation of its current resources. An enterprise carries out one or more activities at one or more locations. An enterprise may be a sole legal unit.’ (Eurostat-OECD 2007).

The social security contributions are subject to strict control. The NSSO declarations are filled out electronically by the employer, and missing declarations or unexpected changes in employment are checked by NSSO analysts. This ensures continuity of the firm identification number and makes the data unlikely to be contaminated by measurement error.

Temporary work agencies are left out from the analysis in this paper because the high job turnover in this industry confuses the discussion of average job reallocation.

See, for example, Benedetto et al. (2007) for a discussion of these practices in the USA.

In Belgium, small firms do not need to file full annual accounts or install a work council (with fewer than 100 employees, turnover below 7.3 m EUR, and balance sheet total below 3.65 m EUR).

The matching procedure used by Statistics Belgium is based on the Term Frequency—Inverse Document Frequency method.

The validation process is carried out by making use of the comprehensive business ‘datawarehouse’ DBRIS. DBRIS is a relational database of all Belgian firms, which links information at the firm level of a vast set of administrative sources (national register of legal entities, Annual Accounts, VAT declarations, Social Security declarations,…), business surveys (Structure of Enterprises Survey, Structure of Earnings Survey,…), and statistical registers on enterprise ownership and control structure (including consolidations, participations, and FDI registered by the National Bank of Belgium and the European Group Register).

The approach of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (Pinkston and Spletzer 2002) and Statistics Canada (Dixon and Rollin 2012) is to collapse both firms into a consolidated employer and calculate employment change at the level of this merged entity. For aggregate measures of job creation and destruction, our strategy yields the same result as this approach. The disadvantage of using a consolidated entity is that the firm counts will be inconsistent across time and, more importantly, the relation between firm size and firm growth will be biased. Indeed, the size of the consolidated entity is by construction larger than those of the original firms.

Rapidly growing firms have an incentive to split up activities into smaller legal units to remain below the size threshold for legal obligations. See also footnote 10.

Benedetto et al. (2007) equally show for US data that the employee-flow method has a nontrivial value added to other linkage methods for identifying missing links between firm identifiers.

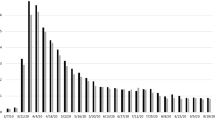

The average sizes of real versus spurious entrants and exits are reported in Table A.2 in the online Appendix.

As mentioned above, Belgian firm ID numbers do not change after a change in ownership or legal form, in contrast to many other countries.

The OECD and Eurostat statistics discussed here are derived from harmonized national business registers. Countries can either apply their own method to obtain consistent longitudinal data or follow the traditional linkage approach recommended by Eurostat-OECD as discussed above.

Regressions of continuing firms include 1.6 million firm-year observations; those of all firms 1.7 million.

The decomposition is given in the online Appendix E.

By definition, net employment growth is not affected by the linkage procedures since they only redefine the reallocation of jobs across firms.

References

Abowd, J. M., & Kramarz, F. (1999). The analysis of labor markets using matched employer-employee data. In O. C. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics Volume 3, part B (Vol. 3, pp. 2629–2710). North Holland: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/S1573-4463(99)30026-2.

Abowd, J. M., Corbel, P., & Kramarz, F. (1999). The entry and exit of workers and the growth of employment: an analysis of French establishments. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(2), 170–187. doi:10.1162/003465399558139.

Acs, Z. J., & Armington, C. (1998) Longitudinal establishment and enterprise microdata (LEEM) documentation. CES 98–9, Center for Economic Studies, US Bureau of the Census. ftp://ftp2.census.gov/ces/wp/1998/CES-WP-98-09.pdf.

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1989). Births and firm size. Southern Economic Journal, 56(2), 467–475. doi:10.2307/1059223.

Albaek, K., & Sorensen, B. E. (1998). Worker flows and job flows in Danish manufacturing, 1980–1991. The Economic Journal, 108, 1750–1771. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00370.

Baldwin, J. R., & Gorecki, P. K. (1987). Plant creation versus plant acquisition. The entry process in canadian manufacturing. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 5(1), 27–41. doi:10.1016/0167-7187(87)90004-X.

Baldwin, J. R., Dupuy, R., & Penner, W. (1992). Development of longitudinal panel data from business registers: The Canadian experience. Statistical Journal of the United Nations, 9, 289–303.

Bartelsman, E., Scarpetta, S., & Schivardi, F. (2005). Comparative analysis of firm demographics and survival: evidence from micro-level sources in OECD countries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 14(3), 365–391. doi:10.1093/icc/dth057.

Benedetto, G., Haltiwanger, J. C., Lane, J., & McKinney, K. (2007). Using worker flows to measure firm dynamics. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 25(3), 299–313. doi:10.1198/073500106000000620.

Bycroft, C (2003). Record linkage in LEED: An overview. Statistics New Zealand. http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/income-and-work/employment_and_unemployment/bycroft-record-linkage-in-leed.aspx.

Cabral, L., & Mata, J. (2003). On the evolution of the firm size distribution: facts and theory. The American Economic Review, 93(4), 1075–1090. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3132279.

Campbell, J. R. (1998). Entry, exit, embodied technology, and business cycles. Review of Economic Dynamics, 1(2), 371–408. doi:10.1006/redy.1998.0009.

Caves, R. E. (1998). Industrial organization and new findings on the turnover and mobility of firms. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(4), 1947–1982. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2565044.

Caves, R. E., & Porter, M. E. (1977). From entry barriers to mobility barriers: Conjectural decisions and contrived deterrence to new competition. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 91(2), 241–262. doi:10.2307/1885416.

Clayton, R. L., & Spletzer, J.R. (2009). Business employment dynamics. In T. Dunne, J. Bradford Jensen, & M. J. Roberts (Eds.), Producer dynamics: New evidence from micro data (pp. 125–147). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. http://papers.nber.org/books/dunn05-1.

Contini, B., Leombruni, R., Pacelli, L., & Villosio C. (2007). Wage mobility and dynamics in Italy in the 90’s. NBER working paper no. w13029. http://ssrn.com/abstract=979934.

Davis, S., Haltiwanger, J. C., & Schuh, S. (1996a). Job creation and destruction. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Davis, S., Haltiwanger, J. C., & Schuh, S. (1996b). Small business and job creation: Dissecting the myth and reassessing the facts. Small Business Economics, 8(4), 297–315. doi:10.1007/BF00393278.

Dixon, J., & Rollin A.-M. (2012). Firm dynamics: Employment growth rates of small versus large firms in Canada. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2141812.

Dunne, T., Roberts, M. J., & Samuelson, L. (1988). Patterns of firm entry and exit in U.S. manufacturing industries. RAND Journal of Economics, 19(4), 495–515. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2555454.

Dunne, T., Roberts, M. J., & Samuelson, L. (1989). The growth and failure of U.S. manufacturing plants. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), 671–698. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2937862

Eriksson, T., & Kuhn, J. M. (2006). Firm spin-offs in Denmark 1981–2000. Patterns of entry and exit. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24(5), 1021–1040. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2005.11.008.

Eurostat-OECD (2007). Eurostat-OECD manual on business demography statistics. Luxembourg: European Communities and OECD. doi:10.1787/9789264041882-en.

Geroski, P. A. (1995). What do we know about entry? International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 421–440. doi:10.1016/0167-7187(95)00498-X.

Geurts, K., & Van Biesebroeck, J. (2014). Job creation, firm creation, and de novo entry. CEPR discussion paper no. 10118. https://feb.kuleuven.be/drc/CES/research/dps-papers/dps14/dps1425.pdf.

Geurts, K., Ramioul M., & Vets, P. (2009). Employee flows to improve measures of job creation and destruction and of firm dynamics. The case of Belgium. HIVA working paper, KU Leuven. http://gcoe.ier.hit-u.ac.jp/CAED/papers/id058_Geurts_Ramioul_Vets.pdf.

Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. S., & Miranda, J. (2013). Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 347–361. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00288.

Jarmin, R. S., & Miranda, J. (2002). The longitudinal business database. Center for economic studies discussion paper CES-WP-02-17. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2128793.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50(3), 649–670. doi:10.2307/1912606.

Korkeamäki, O., & T. Kyyrä. (2000). Integrated panel of Finnish companies and workers. VATT discussion paper 226. Helsinki: Government Institute for Economic Research. http://econpapers.repec.org/paper/ferdpaper/226.htm.

Mata, J. (1993). Entry and type of entrant. Evidence from Portugal. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 11(1), 101–122. doi:10.1016/0167-7187(93)90038-E.

Mata, J., Portugal, P., & Guimaraes, P. (1995). The survival of new plants: Start-up conditions and post-entry evolution. International Journal of Industrial Organisation, 13(4), 459–481. doi:10.1016/0167-7187(95)00500-5.

Mikkelson, G., Unger, L. I., & LeBel, D. (2006). Identifying and accounting for mergers and acquisitions in measuring employment. Washington: BLS Statistical Survey Papers. http://www.bls.gov/ore/pdf/st060160.pdf.

Muendler, M. A., Rauch, J. E., & Tocoian, O. (2012). Employee spinoffs and other entrants: Stylized facts from Brazil. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 30, 447–458. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2012.02.001.

OECD. (2015). Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2015. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/entrepreneur_aag-2015-en.

Persson, H. (1998). Job flows and worker flows in Sweden 1986-1995. In H. Persson (Ed.), Essays on labour demand and career mobility (pp. 1–84). Stockholm: Swedish Institute for Social Research.

Persson, H. (2004). The survival and growth of new establishments in Sweden, 1987–1995. Small Business Economics, 23(5), 423–440. doi:10.1007/s11187-004-3992-7.

Pesola, H. (2009). Labour market transitions following foreign acquisitions. Helsinki: HECER Discussion Paper No. 251. http://ethesis.helsinki.fi/julkaisut/eri/hecer/disc/251/labourma.pdf.

Pinkston, J. C., & Spletzer, J. R. (2002). Annual measures of job creation and job destruction created from quarterly microdata. Washington: BLS Statistical Survey Papers. www.bls.gov/ore/pdf/st020230.pdf.

Reynolds, P., Storey, D. J., & Westhead, P. (1994). Cross-national comparisons of the variation in new firm formation rates. Regional Studies, 28(4), 443–456. doi:10.1080/00343409412331348386.

Robertson, K., L. Huff, G. Mikkelson, T. Pivetz, & A. Winkler. (1999). Improvements in record linkage processes for the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Business Establishment list. In Record linkage techniques—1997: Proceedings of an international workshop and exposition (pp. 212–221). Washington, DC: National Academy Press. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/6491/record-linkage-techniques-1997-proceedings-of-an-international-workshop-and.

Hethey T., & Schmieder, J. (2013). Does the use of worker flows improve the analysis of establishment turnover? Evidence from German administrative data. NBER working paper no. 19730. doi:10.3386/w19730.

Storey, D. J. (1991). The birth of new firms. Does unemployment matter? A review of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 3(3), 167–178. doi:10.1007/BF00400022.

Vilhuber, L. (2008). Adjusting imperfect data: Overview and case studies. In E. P. Lazear, & K. L. Shaw (Eds.), The structure of wages: An international comparison (pp. 59–80). University of Chicago Press. doi:10.3386/w12977.

Wagner, J. (2007). Exports and productivity: A survey of the evidence from firm-level data. The World Economy, 30(1), 60–82. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.00872.x.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the valuable advice of Jo Van Biesebroeck. I am also grateful to the Belgian National Social Security Office (NSSO), in particular Peter Vets for collaboration on the development of the employee-flow method, and to Statistics Belgium, in particular Youri Baeyens and Antonio Fiordaliso for providing firm linkages created for the Eurostat Structural Business Statistics. I also thank Malcolm Brynin and Alex Schmitt for helpful suggestions, and three anonymous referees for valuable comments. Financial support from ERC Grant No. 241127 and KU Leuven Program Financing is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Geurts, K. Longitudinal firm-level data: problems and solutions. Small Bus Econ 46, 425–445 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9693-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9693-6

Keywords

- Firm dynamics

- Job creation and job destruction

- Firm-level microdata

- Linked employer–employee data

- Firm linkage