Abstract

Objective

This paper describes the role of an agency Clinical Director in developing a project to assess and begin to address obesity-related health problems of patients treated in a community-based mental health clinic in New York City. After a five year review of outpatient deaths revealed a high rate of deaths from cardiovascular and diabetes-related issues, the Clinical Director assembled a group of clinicians, researchers, and administrative staff to design a pilot project to assess health and nutrition status of primarily Hispanic day treatment patients with severe and persistent mental illness.

Method

About 69 of the 105 patients at the clinic were assessed by chart review, interview about nutritional habits and medical care, and somatic measurements for blood pressure, weight, girth, body mass index (BMI), glucose and lipid levels.

Results

Patients were predominantly between the ages of 25 and 64 years, 51% were female, and 78% were Hispanic. Around 57% were diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, 86% were receiving antipsychotic medications, and 25% were on two or more antipsychotics. Only 11% of the women and 41% of the men had normal weight. A total of 29% of the women and 18% of the men were overweight (BMI = 25–29.9); and an additional 60% of the women and 41% of the men were obese (BMI ≥ 30). Atypical antipsychotic treatment was significantly associated with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) (chi sq = 5.5, df = 1, P < 0.025). Using American Heart Association criteria, waist measurements showed significant abdominal obesity among female patients. Blood pressure was elevated in 77% of the patients: 45% were pre-hypertensive with BP 120–139/80–89 and 32% were hypertensive with BP ≥ 140/90. About 53% had elevated random blood glucoses (>110 mg/dl). On the positive side, patients generally had had recent medical follow-up, and most had adequate cooking facilities.

Conclusions

This project revealed that these predominantly Hispanic, severely mentally ill individuals were at high risk for cardiac illness, highlighting the need for developing culturally-sensitive interventions in urban outpatient psychiatric settings. Findings were disseminated in educational presentations and clinical discussions, and have mobilized an institutional effort to significantly improve medical monitoring for these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent data have suggested that the United States is experiencing an obesity epidemic, with consequences including increased morbidity and mortality [1]. Obesity can induce the development of a metabolic syndrome, and worsen the course of illnesses including diabetes, hypertension, and cerebrovascular and coronary artery diseases. Obesity-related medical problems are particularly evident among individuals diagnosed with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI), especially those with schizophrenia [2, 3] and bipolar disorder [4]. Behavioral factors may include unhealthy dietary habits, and high rates of smoking and use of alcohol and street drugs [5]. Numerous medications used to treat patients with SPMI, such as olanzapine and clozapine, are associated with weight gain [6–12]. Such patients often receive inadequate management of their medical illnesses [13]. Individuals with SPMI in urban settings may face particular problems, which may be exacerbated by poverty, cultural issues, and other factors.

The Washington Heights Community Service (WHCS) is a university-affiliated outpatient program in upper Manhattan which serves approximately 1000 individuals, most of whom are Hispanic. WHCS is a unit of the New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI). During the period of January 2000 to December 2004, the Clinical Director of NYSPI, together with other clinical and administrative staff, conducted a review of morbidity and mortality in the service. About 22 deaths were found. (see Table 1 ) There were 13 deaths from unexpected natural, causes, many of which occurred in relatively young people: Around 18 of the 22 patients were between the ages of 22 and 64 years of age. Of the 13 unexpected deaths, most individuals carried diagnoses of schizophrenia, 5 with paranoid schizophrenia, 4 with undifferentiated schizophrenia, and 2 with schizoaffective disorder. Cardiovascular events were the cause of death in 8 cases; diabetes, in 2 cases; stroke, in 1 case and perforated ulcer in 1 case. These findings were reviewed by the Clinical Director (D.H.) and were discussed by the institution’s clinical and administrative staff, including risk management and quality improvement staff, leading to the conclusion that many individuals enrolled in the program could be facing serious health issues.

The Clinical Director established a work group to address these problems, starting with a literature review. A variety of studies have been done on the correlation of obesity and chronic mental illness [14–18]. The recently published CATIE study [19] demonstrated that among the atypical antipsychotics, olanzapine was particularly associated with weight gain, although over 10% of patients on all medicines except ziprasidone gained 7% or more of body weight during the study. Only a few studies have focused on naturalistic patient populations in institutionalized or community settings [20, 21], and no studies were found that focused on a patient population from a poor, urban, predominately Hispanic neighborhood. The group decided to perform its own quality improvement project, to assess the health status of predominantly Hispanic outpatients in an urban psychiatric treatment program looking for demographic, medical and behavioral variables that might contribute to obesity-related illnesses The group’s hypotheses were: (1) there would be a high prevalence of obesity, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and hyperlipidemia, often unaddressed by clinical staff; (2) atypical antipsychotic use would be associated with obesity; and (3) patients would have poor access to medical care and adequate cooking facilities, which could exacerbate the medical problems. Depending on the findings, the group’s intention was to modify clinical and administrative policies and procedures to enable better assessment and treatment of these health issues.

Method

A multidisciplinary committee of clinicians and administrators in the Columbia University Department of Psychiatry and the New York State Psychiatric Institute developed a project to review the general health status of WHCS outpatients for the purposes of improving the quality of clinical care. The goal was to assess these chronically mentally ill individuals in order to better understand health risks, and to begin to design appropriate and ecologically-valid health-enhancing interventions. The committee consisted of psychiatrists, nurses, nutritionists, occupational therapists, and social workers, in consultation with an eating disorders researcher (M.J.D.) The project received approval by the Institutional Review Board of the NY State Psychiatric Institute as a minimal risk study.

The Inwood Clinic Day Treatment Program of the WHCS was chosen for this review. Of 105 enrollees, clinicians and Quality Improvement staff were able to assess the health status of 69 patients. Most of the patients were frequent attenders of the program. The review included: demographic profile; clinical psychiatric diagnoses; diagnosed medical problems; current medications and dosages; and laboratory tests noted in charts (including fasting and/or random blood glucose, triglycerides, HDL, LDL and total cholesterol). Whether or not the patient had a primary care physician, and the date of their most recent medical examination, were noted. A registered nurse met with each patient to measure vital signs, weight, height, and girth at waist and hips (in order to calculate Body Mass Index (BMI), calculated in kg/m2) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR). Patients were interviewed about their cigarette use, their dietary and nutritional habits, the availability of cooking facilities, and other possible barriers to healthy eating. Data were tabulated into an anonymized database and analyzed by appropriate statistics, including chi square for categorical variables.

Results

Demographics

A total of 51% (N = 35) of the participants were women. About 78% (N = 54) were Hispanic, most of whom were primarily Spanish-speaking, and of Dominican origin; 13% (N = 9) were Caucasian, and 3% (N = 2) were African–American. Subjects were all adults (age ≥ 18 years), with 33% (N = 23) aged 55–64, 20% (N = 14) aged 35–44, and 19% (N = 13) aged 45–54 years. Around 85% (29/34) of the male patients had schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders compared to 46% (16/35) of the female patients (chi sq = 11.9, df = 1, P ≤ 0.001). Five of the male patients had mood disorders (2 with major depression, 2 with bipolar disorder, 1 with dysthymic disorder), and 19 of female patients had mood disorders (12 with major depression, 5 with bipolar disorder, 1 with mood disorder NOS, 1 with dysthymic disorder).

Overall health status and health monitoring

Medical diagnoses noted by treating psychiatric clinicians included hypertension in 29% (N = 20); hyperlipidemia or hypercholesterolemia in 22% (N = 15); diabetes in 17% (N = 12), endocrine disorder in 13% (N = 9); and cardiac disease in 13% (N = 9). Of the 69 patients, only 23% (N = 16) had normal blood pressure (systolic pressure <120 and diastolic <90); 45% (N = 31) were pre-hypertensive (BP 120–139/80–89); and 32% (N = 22) were hypertensive (BP ≥140/≥90).

Lipid and cholesterol levels within the past year were available for only 32% (22/69) of patients. About 9% (2/22) had high cholesterol levels (>239 mg/dl); 50% (N = 11) had borderline levels (200–239 mg/dl); and 41% (N = 9) had normal levels (<200). Around 5% (N = 11) had very high triglyceride levels (>499 mg/dl), 28% (6/22) had high levels (200–499) 23% (N = 5) had borderline high levels (150–199 mg/dl) and 46% (N = 10) had normal levels. A total of 40% (8/20) had LDL levels above 130 mg/dl, and 29% (6/21) had HDL below 40 mg/dl. Of note, none of the 22 patients had total cholesterol levels <200 mg/dl, HDL>59 mg/dl, LDL<100 mg/dl and TG <150 mg/dl. A total of 34 patients were randomly tested for blood glucoses levels. Of these, 47% (N = 16) had elevated levels (>110 mg/dl). Around 20% (7/35) of the female participants and 38% (13/34) of the male participants reported being either current or recent habitual cigarette smokers. Women reported smoking an average of about 10 cigarettes/day, whereas males reported average use of over 20 cigarettes per day.

Obesity, abdominal obesity, and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) in the overall study population and by gender

Women were more likely than men to be overweight, to be more overweight and to have abdominal obesity. About 89% (31/35) of women and 59% (20/34) of men were overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) or obese. Around 51% (35/69) of all patients had a BMI ≥ 30, a level that has been defined as obese and is a strong indicator of a high risk for heart disease, including 60% (21/35) of women and 41% (14/34) of men. On average, the female population was 40 lbs overweight, while the male population averaged 22 lbs overweight.

Regarding abdominal obesity (see Fig. 1), 45% (N = 9/20) of the men with a BMI ≥ 25 had a waist circumference greater than 102 cm, the American Heart Association’s threshold for abdominal obesity for men [22]. The mean waist circumference among these men was 101 ± 8 cm, no different from the AHA standard. Of the 32 women with BMI ≥ 25, 94% (N = 30) had a waist circumference above 88 cm, the AHA threshold for abdominal obesity among women. Women’s mean abdominal girth was 105 ± 12 cm, 17 cm above the AHA threshold.

Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), another measure related to cardiac risk [23, 24] was also assessed in the sample. Levels of 0.85 or greater for women and 0.90 or greater for men are associated with greater risk of MI. 83% (57/69) of the sample had elevated WHR. Mean ± SD WHR for women was 0.89 ± 0.06; 77% (27/35) of women were at or above the women’s risk threshold of 0.85. Mean ± SD WHR for men was 0.99 ± 0.07; 88% (21/34) of men were at or above the male risk threshold of 0.90.

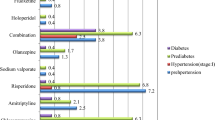

Medications and obesity

About 66 of the 69 patients screened were taking psychotropic medication. Of these, 86% (N = 57) were on antipsychotics, and 26% (N = 17) were on 2 or more antipsychotics. Patients on atypical antipsychotics included 17 on risperidone, 15 on olanzapine, 12 on quetiapine, 3 on clozapine, and 1 on ziprasidone. Patients on typical antipsychotics included 12 on haloperidol (p.o. and/or decanoate), 5 on fluphenazine (p.o. and/or decanoate), 3 on trifluoperazine, 2 on chlorpromazine, 1 on perphenazine, and 1 on thiothixine.

Atypical antipsychotics were associated with being both overweight (BMI > 25) and obese (BMI ≥ 30). Of the 44 patients on atypical antipsychotics, 82% (N = 36) had a BMI ≥ 25 (overweight) vs. 60% (N = 15) of the 25 not on atypicals (chi sq = 3.94, df = 1, P < 0.05) A total of 61% (N = 27) had a BMI ≥ 30, compared to 32% (8/25) of patients not on atypicals (chi sq = 5.5, df = 1, P < 0.025). About 86% (38/44) of patients on atypicals had WHR levels associated with increased cardiac risk, compared to 76% of patients not on atypicals (chi sq = 1.2, df = 1, NS).

No correlation between elevated BMI and mood stabilizers was observed. Of the 20% of patients (14/69) taking mood stabilizers (depakote and/or lithium), 71% were either overweight or obese compared to 75% of the 55 patients not taking mood stabilizers (chi sq = 0.06, df = 1, NS).

Barriers to healthy eating and proper medical care

Virtually all of the patients (67/69) had access to cooking facilities. One patient was without a refrigerator or stove, and 1 had a refrigerator but no stove. Most patients (83%; 57/69) purchased their groceries at a supermarket rather than a bodega or corner store, and most (83%; 57/69) lived within 5 blocks of their primary food shopping location. Most (81%, 56/69) reported that they either prepared their own meals (38%; 26/69), had them prepared by family members, including spouses (30%; 21/69), or shared food preparation activities with spouse or family members (13%; 9/69). All subjects were eligible to receive daily lunch meals when attending the day treatment program.

Contrary to expectation, most patients (84%; 58/69) of the patients reported having a primary care physician, and most (67%; 46/69) reported having a physical exam within the past year. As noted above, however, results of recent laboratory testing were often not available in patient charts.

Discussion

The project has demonstrated that our predominantly Hispanic SPMI outpatients appear to be at high risk for obesity, cardiac, and diabetes-related illnesses. Our findings are consistent with prior mortality data from our WHCS outpatient programs (Table 1), as well as with other data [25] suggesting high rates of metabolic syndrome ranging from 22–60% among schizophrenics. It is not clear whether such risks are greater for Hispanic than non-Hispanic individuals with SPMI. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that there is an urgent need for further research to assess and characterize risk factors, and to begin to develop effective interventions. Within our institution these findings have been disseminated both formally and informally in educational presentations and clinical discussions and have led to a variety of interventions to address these issues. Such interventions include behavioral as well as pharmacological approaches [26], plus better coordination of medical and psychiatric care.

Our findings are consistent with our first hypothesis, that this primarily Hispanic population of SPMI individuals has high levels of obesity, hypertension, and hyperglycemia. Over half of the patients are at high risk for heart disease with a BMI above 30 [22]. Over 80 per cent of the sample had waist-to-hip ratio levels associated with elevated risk of MI. Our second hypothesis, that the use of atypical antipsychotics is associated with being overweight and obese was also confirmed. Because of their striking degree of abdominal obesity which is strongly associated with metabolic risk factors, [22], female patients are at particular risk. Our third hypothesis, that the patients would have poor access to cooking facilities and health care assessments, was not supported. Most WHCS day program patients have access to medical care and adequate cooking facilities. Medical information relevant to psychiatric treatment decisions, such as choice of antipsychotic medication, was often not easily accessible in patient charts. It is likely that many patients meet criteria for metabolic syndrome i.e. 3 or more of the following, including: elevated waist circumference (≥40 inches for men and ≥35 inches for women); elevated triglycerides (≥150 mg/dl), reduced HDL (<40 mg/dl), elevated blood pressure (≥130/85 mm Hg), and elevated fasting glucose (≥100 mg/dl) [24], though missing data in patient charts often made it impossible to calculate this correctly.

Context of these findings

The findings in this sample should be compared to the general U.S. population, in which 65% of adults are overweight (BMI≥25) and 31% are obese (BMI ≥ 30) [27]. Among women in the U.S. between the ages of 40 and 59 years, 38% are obese [28]. There is a paucity of national data on Hispanics of Dominican origin. Among Mexican-Americans, obesity (BMI ≥ 30) has been found among 29% of men and 40% of women [27]. In a study of Hispanic individuals based on self-report, which may underestimate obesity, 24% were obese, a statistic that may vary based on country of origin, gender and years of acculturation [29]. The current day treatment sample shows notably higher rates of overweight (89% for women, 59% for men) and obesity (60% for women, 41% for men) than these comparison samples.

Psychiatric illness, medication side effects, and dietary and behavioral factors are all likely to contribute to these findings. The Hispanic patients in this program are mostly of Dominican origin. Dietary preferences may play a role, particularly in the notable degree of abdominal obesity among female patients. A study of Puerto Rican and Dominican elders [30] found that elevated BMI and abdominal obesity were associated with varying levels of acculturation and dietary preferences. Using factor analysis, Lin identified five predominant dietary patterns among these individuals. A “rice dietary cluster” with high percentages of calories from rice and added cooking oils was associated with significantly elevated BMI and abdominal obesity, in comparison to the four other dietary clusters: fruit and cereal, starchy vegetables, milk and sweets [27]. This diet was found more commonly among less acculturated immigrants. Further assessment of dietary preferences in such patient populations would provide valuable information for interventions.

Impact on clinical services

When these findings were presented to WHCS clinicians, they responded saying that a significant problem “has been demonstrated to us incontrovertibly.” Clinicians agreed that improved health and nutritional monitoring are essential in their clinical population. Consistent with recommendations from Marder et al. [2], the monitoring should include regular assessment of VS, BMI, abdominal girth, laboratory tests (lipids, cholesterol, fasting glucose). In order to identify individuals at risk this information must be recorded in clinical charts more consistently. More regular and better-documented communication with primary care physicians would also be useful. Finally, the clinicians expressed an interest in early identification of patients who are at elevated risk. This would allow early interventions in the psychiatric setting, as well as coordination of care with primary care providers. For instance, patients who demonstrate significant weight gain on an atypical antipsychotic medication might be changed to a medication less associated with weight gain and might have more extensive evaluations by their primary care physicians. Patients at very high risk (BMI ≥ 35), would require even more intensive medical follow-up.

Early in the discussions it became clear that rigorous implementation of Marder et al.’s [2] (see Table 2) health monitoring recommendations would require significant changes in clinic policies and documentation process. Most importantly, it would require changes in clinical programming and increased staffing, such as a part-time internal medicine physician on-staff. Staff discussed how behavioral and nutritional programs could be better incorporated into the outpatient setting, especially for patients in the Day Treatment program who receive high intensity services. For instance, blood pressure, abdominal girth and weight could be measured in therapy groups, and group activities could focus on food preparation, portion measurement, food choices, and regular exercise. Psychoeducation could regularly address patients’ concerns about obesity, diabetes, and other health issues. Discussions also suggested a need for culturally sensitive programming. Food preferences [29, 30] and preparation methods may differ by cultural and socioeconomic factors, even within the same ethnic group. Since it is common for patients’ relatives to be involved in food preparation, family involvement would be essential for improving such health outcomes. However, families of such patients may face numerous problems and stressors, and cardiovascular risks faced by one relative may not be the highest immediate priority. Our psychiatric day program, like many others, provides foods for patients, often the patients’ major meal of the day. Modification of these meals, therefore, might also be indicated.

Over the following year, clinicians and administrators began a number of initiatives to address these issues: (1) a review of existing health education, exercise, and nutrition-related programming in the outpatient setting, with the goal of further developing culturally-sensitive interventions; (2) a review of clinical policies and procedures related to health monitoring and interventions, with the goal of designing a health monitoring system for all outpatients; (3) the initiation of two targeted health status research projects for community patients, one for inpatient and the other in an outpatient setting. The inpatient project is assessing patient knowledge about metabolic syndrome and preferences for interventions. The outpatient project is attempting to rigorously implement health monitoring measures recommended by Marder et al. for a small sample of patients receiving atypical antipsychotic medications.

Future projects will include the initiation of more detailed nutritional assessment and education, and adaptation of electronic medical records to develop flags for health risk indices, such as weight gain on atypical antipsychotics. An application for grant funding for a research project to adapt a program for behavioral and nutritional intervention developed by Ganguli and colleagues [31] to our Hispanic outpatients has been submitted.

Limitations

This study is limited by its small sample size, its cross-sectional study design, and its assessment of only one clinical setting. The 69 subjects assessed in this study may differ from the 35 in the same program who were not assessed, with regard to medications prescribed, medical problems encountered and other factors. Laboratory results obtained from psychiatric charts may underestimate the adequacy of medical follow-up. In further studies, it would be important to know how these patients compare to their relatives without chronic mental disorders, as well as to other Hispanic and non-Hispanic populations of chronically mentally ill individuals. While it is unclear how WHCS study subjects’ health status (obesity, hypertension, etc.) compares to other groups, they are clearly at risk for negative health outcomes.

Conclusions

By a combination of formal and informal authority [32], this Clinical Director-initiated project has mobilized the organization’s efforts to address a significant medical problem among psychiatric outpatients. Davidoff and Batalden [33] have described a process of making observations in quality improvement projects, followed by more systematic assessment of the problem, followed by development of an intervention which can then be documented for publication, and be compared, replicated and evaluated in other settings. Beside this current project, we have pursued this approach in other arenas, including decreasing seclusion and restraint [34], and in instituting a patient coping agreement [35]. Such an approach can link clinical care, policy issues, utilization review/quality assurance procedures, and the development of important new clinical research. Clinical Directors working in academic medical settings that include community services have the opportunity to develop such synergies to effectively advance clinical care, service delivery, and patient care research.

References

Moktad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, et al.: Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. Journal of the American Medical Association 289:76–79, 2003.

Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al.: Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1334–1349, 2004.

Allison DB, Fontaine DR, Heo M, et al.: The distribution of body mass index among individuals with and without schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:215–220, 1999.

McElroy SL, Frye MA, Suppes T, et al.: Correlates of overweight and obesity in 644 patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:201–213, 2002.

Dalak GW, Healy DJ, Meador-Woodruff JH: Nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: A clinical phenomena and laboratory findings. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1490–1501, 1998.

Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, et al.: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain; a comprehensive research synthesis. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1686–1696, 1999.

Virk S, Schwartz TL, Jindal S, et al.: Psychiatric medication induced obesity: An aetiologic review. Obesity Reviews 5:167–170, 2004.

Nasrallah H: A review of the effect of atypical antipsychotics on weight. Psychoneuroendocinology 28(suppl 1):83–86, 2003.

Blackburn GL: Weight gain and antipsychotic medication. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(suppl 8):36–41, 2000.

Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Kysar L, et al.: Novel antipsychotics: Comparison of weight gain liabilities. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 158:765–774; correction 158:1759, 2001.

Bustillo JR, Buchanan RW, Irish D, et al.: Differential effect of clozapine on weight: A controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:817–819, 1996.

Vanina Y, Podolska A, Sedky K, et al.: Body weight changes associated with psychopharmacology. Psychiatric Services 53:842–847, 2002.

Jones LE, Clarke W, Carney CP: Receipt of diabetes services by insured adults with and without claims for mental disorders. Medical Care 42:1167–1175, 2004.

Homel P, Casey D, Allison DB: Changes in body mass index for individuals with and without schizophrenia, 1987–1996. Schizophrenia Research 55:277–284, 2002.

Ganguli R, Brar JS, Ayrton Z: Weight gain over 4 months in schizophrenia patients: A comparison of olanzapine and risperidone. Schizophrenia Research 49:261–267, 2001.

Basson BR, Kinon BJ, Taylor CC, et al.: Factors influencing acute weight change in patients with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine, haloperidol, or risperidone. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62:231–238, 2001.

Bustillo JR, Buchanan RW, Irish D, et al.: Differential effect of clozapine on weight: A controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:817–819, 1996.

Elmslie JL, Silverstone JT, Mann JL, et al.: Prevalence of overweight and obesity in bipolar patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:179–184, 2000.

Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al, the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators: Effectiveness of Antipsychotic Drugs in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 353:1209–1223, 2005.

Martinez JA, Velasco JJ, Urbistondo MD: Effects of pharmacological therapy on anthropometric and biochemical status of male and female institutionalized psychiatric patients. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 13:192–197, 1994.

Susce MT, Villanueva N, Diaz FJ, et al.: Obesity and associated complications in patients with severe mental illnesses: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:167–173, 2005.

Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Cleeman JI, et al.: Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association Conference on Scientific Issues Related to Definition. Circulation 109:433–438, 2004.

Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al.: Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 364:937–52, 2004.

Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al.: Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27000 participants from 52 countries: A case-control study. Lancet 366:1640–1649, 2005.

Meyer J, Koro CE, L’Italien GJ: The metabolic syndrome and schizophrenia: A review. International Journal of Psychiatry 17:173–180, 2005.

Gracious BL, Meyer AE: Psychotropic-induced weight gain and potential pharmacologic treatment strategies. Psychiatry 2005; 36–42, 2005.

Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Journal of the American Medical Association 285:2486–2497, 2001.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al.: Prevalence and trends in obesity among U.S. adults, 1999–2000. Journal of the American Medical Association 288:1723–1727, 2002.

Khan LK, Sobal J, Martorell R: Acculturation, socioeconomic status, and obesity in Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, and Puerto Ricans. International Journal of Obesity 21:91–96, 1997.

Lin H, Bermudez OI, Tucker KL: Dietary patterns of Hispanic elders are associated with acculturation and obesity. Journal of Nutrition 133:3651–3657, 2003.

Brar JS, Ganguli R, Pandina G, et al.: Effects of behavioral therapy on weight loss in overweight and obese patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:205–212, 2005.

Ranz J, McQuistion HL, Stueve A: The role of the community psychiatrist as medical director: A delineation of job types. Psychiatric Services 51:930–932, 2000.

Davidoff F, Batalden P: Toward stronger evidence on quality improvement. Draft publication guidelines: The beginning of a consensus project. Quality and Safety in Health Care 14:319–325, 2005.

Hellerstein DJ, Staub AB, LeQuesne E: Decreasing the use of restraint and seclusion among psychiatric inpatients, Institute on Psychiatric Services, 2006 CME Syllabus and Proceedings Summary, American Psychiatric Association, Arlington VA, 2006, 50.

Hellerstein DJ, Almeida G: Behavioral coping preferences of psychiatric inpatients, New Research Abstracts, Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Arlington VA, 2005, 283.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Health Promotions Funding Award grant from the New York State Office of Mental Health Bureau of Health Services, and a grant from the Frontier Fund of the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hellerstein, D.J., Almeida, G., Devlin, M.J. et al. Assessing Obesity and Other Related Health Problems of Mentally Ill Hispanic Patients in an Urban Outpatient Setting. Psychiatr Q 78, 171–181 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-007-9038-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-007-9038-y