Abstract

Feline calicivirus (FCV) often causes respiratory tract and oral disease in cats and is a highly contagious virus. Widespread vaccination does not prevent the spread of FCV. Furthermore, the low fidelity of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of FCV leads to the emergence of new variants, some of which show increased virulence. Currently, few effective anti-FCV drugs are available. Here, we found that germacrone, one of the main constituents of volatile oil from rhizoma curcuma, was able to effectively reduce the growth of FCV strain F9 in vitro. This compound exhibited a strong anti-FCV effect mainly in the early phase of the viral life cycle. The antiviral effect depended on the concentration of the drug. In addition, germacrone treatment had a significant inhibitory effect against two other reference strains, 2280 and Bolin, and resulted in a significant reduction in the replication of strains WZ-1 and HRB-SS, which were recently isolated in China. This is the first report of antiviral effects of germacrone against a calicivirus, and extensive in vivo research is needed to evaluate this drug as an antiviral therapeutic agent for FCV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Caliciviruses are non-enveloped, small, positive-strand RNA viruses that are divided into five genera: Norovirus, Lagovirus, Sapovirus, Vesivirus, and Nebovirus [1]. The absence of an animal cell model for most caliciviruses has restricted our understanding of their biology. In particular, infection with human noroviruses (HuNoVs) has caused viral epidemic gastroenteritis globally in people of all ages [38]. Feline calicivirus (FCV) and murine norovirus have been used widely as model systems [39], and this has contributed to our understanding of HuNoVs. FCV belongs to the genus Vesivirus and is a highly contagious pathogen that is widely distributed in the feline population [41]. Previous FCV isolates mainly induced upper respiratory tract disease and oral ulceration [22, 23, 31, 32] with a low mortality rate (~2 %) [2, 40]. However, several outbreaks with high mortality (up to 60 %) have been reported in recent years [24].

The gene encoding the capsid protein of FCV contains a variable region [33], and the evolutionary rate in this region ranges from 1.3 × 10−2 to 2.6 × 10−2 substitutions/nucleotide/year [4]. FCV has the highest evolutionary rate among viruses [4]. Although there is only one serotype of FCV, the variability of its main antigen VP1 often contributes to a lack of efficacy of vaccination, and widespread vaccination does not prevent the spread of FCV [19]. In natural infections, cats that have recovered fully from an FCV infection are not protected against infection with other FCV strains [21]. In addition, FCV variants can inhibit or evade the host immune response and persist in cats [4]. After recovery from FCV infection, the clinical symptoms disappear, but many cats continue shedding virus for more than 30 days or even several years [32]. Our previous study found that FCV strain 2280 cannot induce IFN-β expression in vitro [34], which may be a key factor for survival of FCV in cats. Failure to efficiently control FCV infection leads to a high prevalence of FCV. FCV vaccines reduce the duration and severity of clinical signs but do not inhibit virus shedding or infection [25].

Since FCV vaccines do not provide a complete protection, it is urgent to develop an effective and safe antiviral drug for monotherapy or combination treatment. Production of type I interferons (IFNs), which are involved in antiviral responses and have broad-spectrum antiviral activities, is triggered by the presence of viral dsRNA or by-products of viral replication [10]. However, many viruses have evolved multiple strategies to evade or inhibit the IFN response [5–7, 35–37]. In vitro infection with some FCV strains does not result in activation of the IFN-β promoter [34], thus allowing these viruses to evade the IFN response.

Several treatment strategies against FCV disease have been reported [30, 41]. Phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMO) can function as efficient drugs to control FCV disease [30] and have been tested in natural outbreaks of FCV. Mefloquine is a human-approved pharmaceutical compound that has been demonstrated to be effective in the treatment of FCV infections [18]. Combination treatment with Mefloquine and “recombinant feline interferon ω” (rFeIFN-ω) results in a higher efficiency in controlling FCV infection [18]. However, the unfavorable aspects of many drug metabolism pathways might restrict their application [18]. Lithium chloride (LiCl) is widely applied as an important therapeutic agent for nervous system disorders [15], including Alzheimer’s disease [8], and for serous ovarian cancer [20] and diabetes [12]. Several studies have suggested that LiCl can act as an antiviral agent for inhibiting the growth of viruses, such as coronavirus [27], herpes simplex virus type 1 [29], porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) [11] and infectious bronchitis virus [13]. Moreover, LiCl can suppress host inflammatory responses [11], regulate cell apoptosis [27], and restore the synthesis of host proteins in virus-infected cells [43]. Our previous study found that LiCl can efficiently suppress FCV replication in in vitro [41]. However, antiviral therapy with a single drug often causes the emergence of drug-resistant FCV strains. In addition, the high evolutionary rate of FCV [4] makes it necessary to identify more antiviral drugs.

Germacrone is one of the main constituents in volatile oil from rhizoma curcuma [42]. It can suppress angiogenesis and metastasis, which contributes the restriction of cell proliferation. Due to its potential to inhibit the growth of tumour cells, germacrone has been widely used as an anti-cancer drug in China [17]. It has been demonstrated that germacrone can inhibit the replication of H1N1 and H3N2 influenza A virus in vitro by impairing the attachment/entry step and early events in the viral life cycle [14]. Another study also found that germacrone may be a potential drug against porcine parvovirus (PPV) infection [3]. In the current study, the antiviral effects of germacrone on FCV replication were investigated by measuring changes in viral RNA (vRNA) levels and virus yield. The results indicated that germacrone can act as an efficient antiviral drug against FCV replication.

Materials and methods

Viruses and cells

The FCV strains 2280, Bolin and F9 were obtained from ATCC. Strains HRB-SS and WZ-1 were isolated from ill household cats, as described previously [16, 41]. Crandell-Reese feline kidney (CRFK) cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone) supplemented with 8 % fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin. Virus stocks were propagated in CRFK cells, centrifuged at 4 °C and 12,000 g for 20 min, and kept at -80 °C until used.

Reagents

Germacrone (CAS No. 6902-91-6) was purchased from BELLONCAM, China. It was initially dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 20 mM in 80 % DMSO (v/v). The amount of DMSO was constantly maintained at 0.4 % for all samples. DMSO concentrations below 1 % (v/v) are widely used for poorly soluble polar and nonpolar molecules and are not toxic to retinal neuronal cell lines [9].

Cytotoxicity assay for germacrone

CRFK cells in a 96-well plate (104 cells/well) were prepared prior to the assay. The next day, the culture medium was discarded, and germacrone was added at different concentrations (0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 and 200 μM), diluted in serum-free DMEM. Cells treated with DMSO (0.4 %) were used as a control. After treatment for 24 h, cytotoxicity assays were done using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) (Donjindo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After washing two times with 1× PBS, DMEM (80 μL) and CCK8 solution (20 μL) were added to the cells, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for two hours. The optical density (OD) was determined using an EnSpire® Multimode Plate Reader (PE, USA) with a 450-nm excitation filter [41]. The relative cell viability was calculated as a percentage of that of the mock-treated control cells. Germacrone concentrations below the 50 % cytostatic concentration (CC50) were considered non-toxic.

Antiviral test

To determine antiviral efficacy of germacrone against FCV proliferation, cells were treated for one hour with germacrone at concentrations of 20-100 μM. After incubation, the cells were infected with strain F9 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 TCID50 in the presence of germacrone for one hour. After washing three times with PBS, the cells were exposed to germacrone (20-100 μM) for twelve hours. The time of drug exposure in this test was from one hour before infection until the test endpoint, allowing the step in the viral life cycle at which the drug acts to be determined. The virus yields in cell supernatants were measured, total RNA was isolated from the cells, and the levels of vRNA were determined by real-time RT-PCR.

Analysis of the effect of germacrone on viral attachment

Cells were seeded and cultured for 24 h. Nontoxic concentrations (60-100 μM) of germacrone, or 0.4 % DMSO alone for mock treatment, were mixed with the virus suspension and incubated for one hour at 37 °C. The mixture containing the drug and the virus was then added to the cells, followed by incubation for one hour at 4 °C. The MOI in this assay was 0.1 TCID50. The levels of vRNA in cells were determined by real-time RT-PCR.

Analysis of the effect of germacrone on viral entry

Cells in 24-well plates were inoculated with strain F9 at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50, which was diluted in different concentrations of germacrone (60-100 μM) or 0.4 % DMSO for mock treatment for one hour at 4 °C. The plate was then incubated for one hour at 37 °C. The levels of vRNA were determined by real-time RT-PCR.

Effect of germacrone on viral replication

To further investigate the antiviral efficacy of germacrone, cells were inoculated with strain F9 at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50 for one hour at 37 °C. After the cells were washed three times with 1× PBS, the infected cells were exposed to germacrone at concentrations of 60-100 μM or subjected to mock treatment with 0.4 % DMSO for twelve hours. The recovered virus yields in cell supernatants were determined. The levels of vRNA were determined by real-time RT-PCR.

Time-of-addition assay

To determine which stages of the viral life cycle were affected by the drug, the effects of simultaneous treatment, pre-treatment and post-treatment were evaluated. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates and cultured for 24 hours. (1) Cells were pre-treated with germacrone at a concentration of 60 μM for one hour. After incubation, cells were challenged with strain F9 at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50. (2) Cells were simultaneously exposed to strain F9 at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50 and germacrone (60 μM) for twelve hours. (3) Cells were inoculated with strain F9 at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50 for one hour prior to exposure to 60 μM germacrone at 1, 3, 6 and 9 hpi. The recovered virus yields in cell supernatants were determined at 12 hpi. The levels of vRNA were measured by real-time RT-PCR.

Evaluation of the antiviral activity of germacrone against other FCV strains

The cells was treated with 60 μM germacrone for one hour prior to challenge with strain 2280, Bolin, F9, HRB-SS or WZ-1 at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50. The time of drug exposure was from one hour before challenge until the end of the experiment. The recovered virus yield in the cell supernatant was determined at 12 hpi.

Virus titration

The protocol for virus titration has been described previously [35]. Briefly, virus stocks were diluted 1:10 in free-serum DMEM and applied to the cells. After a one-hour adsorption period, medium containing 1 % FBS was added. At 48-72 h post-inoculation, a cytopathic effect was observed. Following to the protocol of Reed and Müench [26], the viral yields were calculated as the median tissue culture infective dose log10 (TCID50/mL).

Real-time RT-PCR

The protocol for real-time RT-PCR has been described previously [35]. Total RNA from drug-treated or untreated cells was isolated using an RNeasy® Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transcription of RNA into cDNA was performed using a PrimeScript ™ 1st Strand cDNA Kit (Takara, Japan). The following primers for FCV Pro-Pol and GAPDH were designed: FCV-for, 5’-ATGATTTGGGGTTGTGATGT-3’; FCV-rev, 5’-TGGGGCTRTCCATGTTGAT-3’; GAPDH-for, 5’-TGACCACAGTCCATGCCATC-3’; GAPDH-rev, 5’-GCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCA-3’. The procedure for PCR consisted of an initial step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 15 s. The relative level of RNA expression was determined by the 2-∆∆CT method [41]. GAPDH mRNA was analyzed as a loading control.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA)

After washing three times with PBS, cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and then permeabilized with 0.2 % Triton X-100 for 20 min. The cells were washed three times, and a feline anti-FCV serum (1:100, diluted in PBS) was incubated with the cells at room temperature or at 37 °C for one hour. The cells were then incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-cat IgG (1:100, diluted in PBS; Jackson, USA). The cells were then washed three times and incubated with DAPI (1:100, diluted in PBS) at room temperature for 20 min. The fluorescence was examined using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

Statistics

Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and data are presented as the mean ± SD. The significance of differences was analyzed by a one-way ANOVA and an unpaired t-test, using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. In comparisons between the drug- and mock-treated groups, a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant and is indicated as follows: **, P < 0.01.

Results

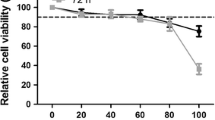

Cytotoxicity of germacrone

Cytotoxicity assays showed that the relative cell viability was greater than 85 % after exposure to germacrone at concentrations ranging from 20 to 100 μM for 24 h, whereas the viability was less than 50 % after treatment with 200 μM germacrone for 24 h (Fig. 1). Treatment with ~100 μM germacrone (below the CC50 value) did not result in a significant difference in cell morphology (data not shown) compared to mock-treated cells. The concentration range of 20-100 μM was therefore selected for antiviral assays.

Cell toxicity assay after germacrone treatment. Cells were pre-exposed to 0.4 % DMSO (mock) or germacrone at concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 or 200 μM for 24 h. Cell toxicity was evaluated using a CCK8 assay. The activity of DMSO-treated cells was considered to be 100 %, and cell toxicity was plotted as the percentage viable cells relative to mock-treated cells. The values represent three independent experiments

Identification of germacrone as an inhibitor of FCV replication in vitro

To evaluate whether germacrone could inhibit FCV proliferation, cells were treated with different concentrations of germacrone (20-100 μM) for one hour prior to infection with strain F9 in the presence of the drug. The results showed that germacrone treatment (20-100 μM) led to a significant reduction of vRNA levels compared to mock treatment, and the inhibitory effect was dose-dependent (Fig. 2A). Treatment with 20 μM or 40 μM germacrone did not affect virus yield significantly, and treatment with 60-100 μM germacrone inhibited viral proliferation by at least tenfold (Fig. 2B).

Evaluation of antiviral effects of germacrone on FCV growth. (A, B) Cells were treated with germacrone at a concentration of 20-100 μM prior to challenge. After a 1-h treatment with germacrone, cells were inoculated with strain F9 at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50 for one hour in the presence of the drug. The time of germacrone treatment was from one hour before challenge until the end of the experiment. Relative vRNA levels in cells (A) and the virus yields in supernatants from infected cells (B) were determined. (C) CRFK cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of germacrone at 37 °C for one hour or 0.4 % DMSO (mock) and then infected with strain F9 at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50 for one hour. Uninfected cells were used as negative controls. Fluorescence (×40) was observed at 12 hpi

In an IFA experiment, a strong signal was observed in mock-treated cells as well as in cells treated with 40 μM germacrone at 12 hpi. The fluorescent signals decreased after treatment with 60, 80 and 100 μM germacrone (Fig. 2C). No fluorescent signals were observed in the cell control group.

These results indicated that pre-treatment with 60-100 μM germacrone resulted in a significant reduction in both virus titer and vRNA levels in a concentration-dependent manner.

Germacrone treatment does not affect FCV attachment or entry

To investigate whether the antiviral effect of germacrone is associated with a reduction in virus attachment and entry into cells, germacrone (60 μM-100 μM) was mixed with a virus suspension for one hour and then added to cells, and the plate was then incubated for one hour at 4 °C. The amount of vRNA was then measured, and no difference was found between drug-treated and mock-treated samples (Fig. 3A), suggesting that germacrone treatment does not affect viral attachment to cells.

Evaluation of the effects of germacrone treatment on viral attachment and entry. CRFK cells were treated as described in “Materials and methods”, and vRNA levels in groups exposed to germacrone or 0.4 % DMSO (mock) were analyzed during the virus attachment stage (A) and the virus entry stage (B). The data represent three independent experiments

To investigate whether germacrone treatment inhibits FCV entry into cells, the cells were inoculated with virus for one hour at 4 °C, after which the cells were exposed to germacrone (60, 80 and 100 μM) for one hour at 37 °C. The levels of vRNA were determined by quantitative PCR. The vRNA levels were not decreased in germacrone-treated cells (Fig. 3B), indicating that the drug did not affect virion entry.

Germacrone treatment inhibits viral replication

Since germacrone treatment did not affect FCV attachment and entry, we speculated that germacrone might affect viral proliferation. Cells were infected with virus for one hour and then treated with germacrone at a concentration of 60, 80 or 100 μM for twelve hours. The levels of vRNA and recovered virus yields were determined.

Compared to mock-treated cells, germacrone treatment with 60, 80 and 100 μM led to 57.51 %, 59.67 % and 69.27 % decrease, respectively, in the relative vRNA level (Fig. 4A). Moreover, virus loads in the cells treated with 60 μM germacrone were decreased by 100-fold (Fig. 4B).

Evaluation of the effects of germacrone treatment on viral replication. Cells were inoculated with strain F9 at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50 for one hour. The cells were then exposed to germacrone (60-100 μM) at 37 °C for 12 hours. Relative vRNA levels (A) in the cells and virus yields in the cell supernatants (B) were determined

The antiviral effect of germacrone occurs chiefly in the early stage of FCV replication

Further experiments were performed to analyze the inhibitory effect of germacrone against viral proliferation. Cells were exposed to 60 μM germacrone prior to or after virus challenge. As shown in Fig. 5A, a reduction in the amount of vRNA was detected at -1, 0 and 1 hpi but was not observed from 3 h to 9 h in the germacrone-treated groups. Compared to mock-treated cells, the virus loads were significantly reduced in cells treated with germacrone at -1 h, 0 h and 1 h, but no significant reduction was detected from 3 h to 9 h (Fig. 5B). Thus, germacrone treatment chiefly affects the early stage of viral proliferation.

The time-dependent effects of germacrone on FCV replication. Cells were inoculated with strain F9 at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50. The cells were treated with germacrone at the indicated time points. Relative vRNA levels (A) in the cells and virus yields in the cell supernatants (B) were determined at 12 hpi; ‘-1 h’ indicates pre-treatment with germacrone for one hour before virus challenge. The data represent three independent experiments

Germacrone treatment inhibits the replication of field isolates and other reference strains

An antiviral assay was performed to evaluate whether germacrone can affect the replication of other reference strains and field isolates. Following a 1-h treatment with germacrone or mock treatment, cells were infected with different FCV isolates for one hour and treated with 60 μM germacrone for twelve hours. The recovered virus yields were determined at 12 hpi. As shown in Fig. 6, germacrone treatment significantly suppressed the growth of reference strains F9, Bolin and 2280 and field isolates WZ-1 and HRB-SS. After germacrone treatment, a nearly tenfold decrease in virus yield was detected for the reference strains and field isolates compared to mock treatment (Fig. 6).

Inhibitory effects of germacrone on other reference stains and field isolates of FCV. Cells were exposed to 60 μM germacrone for one hour and then inoculated with the indicated FCV strains at an MOI of 0.1 TCID50. The recovered virus yields were determined at 12 hpi. The data represent three independent experiments

Discussion

The family Caliciviridae is a highly diverse family of human and non-human pathogenic viruses [28]. The human pathogenic norovirus is a major cause of viral gastroenteritis worldwide. For the human pathogenic norovirus, there are no suitable in vitro culture systems, and this has restricted vaccine development. Antiviral drugs may be a better method to control human norovirus infection. Feline calicivirus (FCV) has been used widely as model systems to accelerate our learning about HuNoVs. Developing antiviral drugs against FCV may help in controlling human norovirus infection.

Rhizoma curcuma is applied for the treatment of tumors and inflammation in traditional Chinese medicine [8]. Germacrone is a key component of the essential oils isolated from rhizoma curcuma and has been used for antitussive, anti-inflammatory, antidepressant, antifeedant, antifungal, antibacterial and antitumor proposes [4, 17]. Recently, germacrone was shown to inhibit influenza virus replication in a concentration-dependent manner [9].

PPV can cause reproductive failure in sows, and antiviral drugs may be an alternative method to protect animals from PPV infection. Chen et al. reported that pre-exposure with germacrone significantly inhibited PPV replication at an early stage in a concentration-dependent manner [3]. Our study showed that germacrone suppressed FCV replication as well as the production of vRNA and progeny virus. The antiviral effect of germacrone treatment occurred chiefly in the early stage of virus replication in a concentration-dependent manner. The data suggest that germacrone might be a potential drug for the treatment of FCV disease, but further investigation is required to examine its antiviral effect and safety in vivo. Most studies so far have focused on in vitro data, and in vivo data are urgently needed to explore safety issues.

Since germacrone does not affect FCV and PPV attachment and entry, and inoculation prior to infection results in the highest inhibitory efficiency, as in the case of influenza virus [14], we speculate that treatment with germacrone may affect the expression of host genes, some of which may be required for viral replication.

We infer that germacrone may be protective against infection with most FCV strains. Although FCV evolves quickly due to the low fidelity of its RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, only one serotype has been identified so far. Another report also demonstrated that strain F9 and seven other strains have similar sensitivity to mefloquine treatment [18]. Moreover, all of the strains used in this study, including the currently circulating viruses from China, showed a similar sensitivity to germacrone treatment. Our results suggest that germacrone can be used as an effective broad-spectrum anti-FCV drug, either alone or in combination with other anti-FCV compounds for the treatment of cats. Additionally, the used of a combination of germacrone and existing antiviral drugs might help to prevent the development of resistance to drugs developed for FCV in the future.

Conclusions

In this study, germacrone was identified as a potent inhibitor of FCV replication when present at low concentrations. Germacrone treatment chiefly affected the early phase of viral replication. Moreover, the evaluation of its inhibitory effect against a calicivirus extends the broad spectrum of its antiviral effects. More investigation is needed to optimize this drug for clinical application for the treatment of FCV. It is also necessary to analyze the effectiveness of germacrone against other feline viruses.

References

Abente EJ, Sosnovtsev SV, Bok K, Green KY (2010) Visualization of feline calicivirus replication in real-time with recombinant viruses engineered to express fluorescent reporter proteins. Virology 400:18–31

Cave TA, Thompson H, Reid SW, Hodgson DR, Addie DD (2002) Kitten mortality in the United Kingdom: a retrospective analysis of 274 histopathological examinations (1986 to 2000). Vet Rec 151:497–501

Chen Y, Dong Y, Jiao Y, Hou L, Shi Y, Gu T, Zhou P, Shi Z, Xu L, Wang C (2015) In vitro antiviral activity of germacrone against porcine parvovirus. Arch Virol 160:1415–1420

Coyne KP, Gaskell RM, Dawson S, Porter CJ, Radford AD (2007) Evolutionary mechanisms of persistence and diversification of a calicivirus within endemically infected natural host populations. J Virol 81:1961–1971

de Los Santos T, de Avila Botton S, Weiblen R, Grubman MJ (2006) The leader proteinase of foot-and-mouth disease virus inhibits the induction of beta interferon mRNA and blocks the host innate immune response. J Virol 80:1906–1914

Didcock L, Young DF, Goodbourn S, Randall RE (1999) The V protein of simian virus 5 inhibits interferon signalling by targeting STAT1 for proteasome-mediated degradation. J Virol 73:9928–9933

Fensterl V, Grotheer D, Berk I, Schlemminger S, Vallbracht A, Dotzauer A (2005) Hepatitis A virus suppresses RIG-I-mediated IRF-3 activation to block induction of beta interferon. J Virol 79:10968–10977

Forlenza OV, de Paula VJ, Machado-Vieira R, Diniz BS, Gattaz WF (2012) Does lithium prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Drug Aging 29:335–342

Galvao J, Davis B, Tilley M, Normando E, Duchen MR, Cordeiro MF (2014) Unexpected low-dose toxicity of the universal solvent DMSO. FASEB J (official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology) 28:1317–1330

Haller O, Kochs G, Weber F (2006) The interferon response circuit: induction and suppression by pathogenic viruses. Virology 344:119–130

Hao HP, Wen LB, Li JR, Wang Y, Ni B, Wang R, Wang X, Sun MX, Fan HJ, Mao X (2015) LiCl inhibits PRRSV infection by enhancing Wnt/beta-catenin pathway and suppressing inflammatory responses. Antiviral Res 117:99–109

Lavoie J, Hebert M, Beaulieu JM (2015) Looking beyond the role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 genetic expression on electroretinogram response: what about lithium? Biol Psychiatr 77:E15–E17

Li J, Yin JC, Sui XW, Li GX, Ren XF (2009) Comparative analysis of the effect of glycyrrhizin diammonium and lithium chloride on infectious bronchitis virus infection in vitro. Avian Pathol 38:215–221

Liao Q, Qian Z, Liu R, An L, Chen X (2013) Germacrone inhibits early stages of influenza virus infection. Antiviral Res 100:578–588

Licht RW (2012) Lithium: still a major option in the management of bipolar disorder. CNS Neurosc Ther 18:219–226

Liu C, Liu Y, Liu D, Guo D, Liu M, Li Y, Qu L (2014) Complete Genome Sequence of feline calicivirus strain HRB-SS from a cat in Heilongjiang Province. Genome announcements, Northeastern China 2

Lu JJ, Dang YY, Huang M, Xu WS, Chen XP, Wang YT (2012) Anti-cancer properties of terpenoids isolated from Rhizoma Curcumae—a review. J Ethnopharmacol 143:406–411

McDonagh P, Sheehy PA, Fawcett A, Norris JM (2015) Antiviral effect of mefloquine on feline calicivirus in vitro. Vet Microbiol 176:370–377

Najafi H, Madadgar O, Jamshidi S, Ghalyanchi Langeroudi A, Darzi Lemraski M (2014) Molecular and clinical study on prevalence of feline herpesvirus type 1 and calicivirus in correlation with feline leukemia and immunodeficiency viruses. Vet Res Forum (an international quarterly journal) 5:255–261

Novetsky AP, Thompson DM, Zighelboim I, Thaker PH, Powell MA, Mutch DG, Goodfellow PJ (2013) Lithium chloride and inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta as a potential therapy for serous ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 23:361–366

Orr CM, Gaskell CJ, Gaskell RM (1980) Interaction of an intranasal combined feline viral rhinotracheitis, feline calicivirus vaccine and the FVR carrier state. Vet Rec 106:164–166

Ossiboff RJ, Parker JS (2007) Identification of regions and residues in feline junctional adhesion molecule required for feline calicivirus binding and infection. J Virol 81:13608–13621

Ossiboff RJ, Sheh A, Shotton J, Pesavento PA, Parker JS (2007) Feline caliciviruses (FCVs) isolated from cats with virulent systemic disease possess in vitro phenotypes distinct from those of other FCV isolates. J Gen Virol 88:506–517

Prikhodko VG, Sandoval-Jaime C, Abente EJ, Bok K, Parra GI, Rogozin IB, Ostlund EN, Green KY, Sosnovtsev SV (2014) Genetic characterization of feline calicivirus strains associated with varying disease manifestations during an outbreak season in Missouri (1995–1996). Virus Genes 48:96–110

Radford AD, Coyne KP, Dawson S, Porter CJ, Gaskell RM (2007) Feline calicivirus. Vet Res 38:319–335

Reed LJ, Münch H (1938) A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Epidemiol 27:493–497

Ren XF, Meng FD, Yin JC, Li GX, Li XL, Wang C, Herrler G (2011) Action Mechanisms of lithium chloride on cell infection by transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus. PloS One 6(5):e18669

Rohayem J, Bergmann M, Gebhardt J, Gould E, Tucker P, Mattevi A, Unge T, Hilgenfeld R, Neyts J (2010) Antiviral strategies to control calicivirus infections. Antiviral Res 87:162–178

Skinner GR, Hartley C, Buchan A, Harper L, Gallimore P (1980) The effect of lithium chloride on the replication of herpes simplex virus. Med Microbiol Immunol 168:139–148

Smith AW, Iversen PL, O’Hanley PD, Skilling DE, Christensen JR, Weaver SS, Longley K, Stone MA, Poet SE, Matson DO (2008) Virus-specific antiviral treatment for controlling severe and fatal outbreaks of feline calicivirus infection. Am J Vet Res 69:23–32

Sosnovtsev SV, Garfield M, Green KY (2002) Processing map and essential cleavage sites of the nonstructural polyprotein encoded by ORF1 of the feline calicivirus genome. J Virol 76:7060–7072

Thiry E, Addie D, Belak S, Boucraut-Baralon C, Egberink H, Frymus T, Gruffydd-Jones T, Hartmann K, Hosie MJ, Lloret A, Lutz H, Marsilio F, Pennisi MG, Radford AD, Truyen U, Horzinek MC (2009) Feline herpesvirus infection. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J Feline Med Surg 11:547–555

Thumfart JO, Meyers G (2002) Feline calicivirus: recovery of wild-type and recombinant viruses after transfection of cRNA or cDNA constructs. J Virol 76:6398–6407

Tian J, Zhang X, Wu H, Liu C, Liu J, Hu X, Qu L (2015) Assessment of the IFN-beta response to four feline caliciviruses: Infection in CRFK cells. Infect Genet Evol J Mol Epidemiol Evol Genet Infect Dis 34:352–360

Wang D, Fang L, Luo R, Ye R, Fang Y, Xie L, Chen H, Xiao S (2010) Foot-and-mouth disease virus leader proteinase inhibits dsRNA-induced type I interferon transcription by decreasing interferon regulatory factor 3/7 in protein levels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 399:72–78

Wang D, Fang L, Bi J, Chen Q, Cao L, Luo R, Chen H, Xiao S (2011) Foot-and-mouth disease virus leader proteinase inhibits dsRNA-induced RANTES transcription in PK-15 cells. Virus Genes 42:388–393

Wang X, Li M, Zheng H, Muster T, Palese P, Beg AA, Garcia-Sastre A (2000) Influenza A virus NS1 protein prevents activation of NF-kappaB and induction of alpha/beta interferon. J Virol 74:11566–11573

Widdowson MA, Monroe SS, Glass RI (2005) Are noroviruses emerging? Emerg Infect Dis 11:735–737

Wobus CE, Thackray LB, Virgin HWT (2006) Murine norovirus: a model system to study norovirus biology and pathogenesis. J Virol 80:5104–5112

Wong WT, Kelman M, Ward MP (2013) Surveillance of upper respiratory tract disease in owned cats in Australia, 2009–2012. Prevent Vet Med 112:150–155

Wu H, Zhang X, Liu C, Liu D, Liu J, Tian J, Qu L (2015) Antiviral effect of lithium chloride on feline calicivirus in vitro. Arch Virol 12:2935–2943

Xia Q, Zhao KJ, Huang ZG, Zhang P, Dong TT, Li SP, Tsim KW (2005) Molecular genetic and chemical assessment of Rhizoma Curcumae in China. J Agric Food Chem 53:6019–6026

Ziaie Z, Kefalides NA (1989) Lithium chloride restores host protein synthesis in herpes simplex virus-infected endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 160:1073–1078

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31402201).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

H. Wu and Y. Liu are co-first authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Liu, Y., Zu, S. et al. In vitro antiviral effect of germacrone on feline calicivirus. Arch Virol 161, 1559–1567 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-016-2825-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-016-2825-8