Abstract

Tall deciduous shrubs are critically important to carbon and nutrient cycling in high-latitude ecosystems. As Arctic regions warm, shrubs expand heterogeneously across their ranges, including within unburned terrain experiencing isometric gradients of warming. To constrain the effects of widespread shrub expansion in terrestrial and Earth System Models, improved knowledge of local-to-regional scale patterns, rates, and controls on decadal shrub expansion is required. Using fine-scale remote sensing, we modeled the drivers of patch-scale tall-shrub expansion over 68 years across the central Seward Peninsula of Alaska. Models show the heterogeneous patterns of tall-shrub expansion are not only predictable but have an upper limit defined by permafrost, climate, and edaphic gradients, two-thirds of which have yet to be colonized. These observations suggest that increased nitrogen inputs from nitrogen-fixing alders contributed to a positive feedback that advanced overall tall-shrub expansion. These findings will be useful for constraining and projecting vegetation-climate feedbacks in the Arctic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-latitude regions are warming nearly four times faster than the global average1, leading to widespread shifts in tundra vegetation2,3,4. One of the earliest observed and most ubiquitous of these shifts is the expansion of tall deciduous shrub canopies5,6,7, particularly in alder, birch, and willow shrubs (Alnus spp., Betula spp., and Salix spp., respectively). These shrubs are strong competitors for resources, able to outcompete prostrate and low-statured plant types for light via tall canopy architecture8, increase soil insulation and moisture via snow accumulation9, and efficiently acquire nutrients via mycorrhizal associations2, which together contribute to rapid expansion rates2,10. Alder shrubs have the additional advantage of a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria, increasing the local availability of nitrogen in soils11. The widespread success and increased dominance of deciduous shrubs across many tundra regions contribute to accelerating regional warming by altering surface energy balance (i.e., decreased albedo)2,6,10 and positive trends in ecosystem productivity and greenness across the pan-Arctic10,12,13,14

Observations of shrub expansion (often termed shrubification) are prevalent across Alaska15,16, Canada17,18, Russia19,20, and northern Europe21,22, where the rate and direction of shrub cover change vary with and modify a suite of environmental variables. Soil moisture and water availability have been shown to regulate the kinetics of reactions involved with shrub growth2, leading to increased shrub expansion in moist soils but limited expansion in saturated soils due to anoxic conditions23,24,25. Forced and passive warming experiments have demonstrated positively enhanced shrub height and width8, similar to that observed in long-term monitoring plots in response to climate warming26. Warmer summer temperatures have also been linked with increased productivity (i.e. normalized difference vegetation index and aboveground biomass)14. Disturbances including frost heave, permafrost thaw, and wildfire may expose mineral soils and/or deepen the active layer (i.e. seasonally thawed soil layer), also promoting shrub recruitment10. In contrast, thermokarst (surface subsidence from permafrost thaw) may facilitate the transition from well-drained to poorly drained terrain, drowning shrubs with increased soil inundation15,20. Due to the complex ecological dynamics that govern the rate and direction of shrub cover change at local to regional scales, our ability to anticipate patch-scale patterns of vegetation change across space and time remains limited. Minimizing uncertainties in key biogeophysical feedback processes in response to projected climate and environmental change, however, relies on understanding patch-scale shrubification dynamics.

As climate and environmental conditions change, shrubs will likely continue to thrive in warmer and longer growing seasons2, propagating across the landscape14,27. However, shrubs cannot expand homogeneously, even within similar gradients of warming3,4,15. While our understanding of the factors that influence shrub dynamics is increasing2,6,10,14,27, our ability to predict the spatially heterogeneous patterns of shrubification across the Arctic remains limited. Here we develop a dynamic shrub patch-scale suitability model capable of predicting the present and projected ceiling (i.e. maximum spatial extent) of tall-shrub and alder-specific expansion. Using 68 years of optical data acquired from uncrewed aerial systems (UAS), aerial photography, and spaceborne observations, we mapped and modeled fine-scale patterns of shrub patch dynamics within a topographically and environmentally heterogeneous region within the continuous-discontinuous permafrost zone. The study region experienced similar rates of warming throughout, ranging from 0.25 to 0.29 °C y−10 as compared to 0.16 to 0.40 °C y−10 for the entire tundra region of Alaska. Specifically, we (1) quantify the patch-scale patterns and rates of change in alder, birch, and willow shrubs, (2) model the spatial extent of present and projected shrub expansion, and (3) upscale field observations of nitrogen fixation via alder root nodules to evaluate the spatially explicit impact of increased nitrogen availability on shrub-to-shrub interactions across space. Results provide new evidence to support a positive feedback between alder expansion and overall tall-shrub expansion while providing new methods to constrain the dynamic advancement of tall shrubs across vast regions of the Arctic.

Results and Discussion

Shrub Patch Dynamics

Tall-shrub canopies were segmented using high-resolution (<3 m) aerial and satellite imagery across a 16,000 km2 region in the central Seward Peninsula of Alaska (Fig. 1a). Three subregions with a total area of 2240 km2 (Fig. 1b-d) were used to represent various environmental and biophysical properties (Table 1) that are known to influence shrub dynamics. We selected our subregions within disparate topographic and moisture gradients, which included subregions that were low-lying and inundated, within well-drained uplands, and a medley of both conditions. Using seamless PlanetScope orthomosaics of two phenoperiods (peak-biomass and senescence) we were able to classify tall shrubs with 94.7% accuracy. As alder leaves senesce later than those of other tall shrubs28, we were able to discriminate between canopies dominated by alder versus a willow and birch shrub complex (henceforth willow-birch). High-resolution shrub mapping indicated shrub extent varied with edaphic conditions within and among subregions (Tables 1, 2).

Map of our study region on the central Seward Peninsula of Alaska, including the full area (a), the western Coastal subregion extending north from Port Clarence Bay to the York Mountains and containing terrain that gradually shifts from low-lying floodplains to sloping uplands as the elevation increases (b), the eastern Upland Hillslope subregion, defined by low water availability, sloping topography, and a mix of volcanic and upland soils, with shrub patches largely confined to drainage networks known as water tracks (c), and the central Floodplains/Foothills subregion, defined by low-lying floodplains, though also comprising a section of the foothills of the Kigluaik Mountains to the south, where shrubs expanded in large clusters (d). The teal triangle marks the location of Mary’s Igloo, Alaska, and the violet square marks the location of the NGEE Arctic Kougarok Hillslope study site. All background images are courtesy of ESRI ArcGIS’s ‘Imagery’ Basemap.

Tall shrubs expanded heterogeneously over 68 years, with a substantially faster rate along hillslope water tracks, floodplains, and on rocky outcrops. These expansion patterns are consistent with prior studies29, likely due in part to the large initial shrub extent and the increased likelihood of seed dispersal. For example, within the central Floodplains/Foothills subregion (Fig. 1d), we identified a 119% (+5.25 km2 y−10) increase in new alder area and 142% (+6.04 km2 y−10) increase in the area of willow-birch, comprising 89 and 38.5% of the total alder and willow-birch expansion in all three subregions, respectively, despite the subregion’s small size (554 km2, 24.7% of the total subregion area). Across our three subregions (Table 2), willow-birch patch area increased 63 km2 (82%) between 1950 and 2018, by laterally expanding and infilling gaps within shrub patches at a rate of ~7 m2 ha−1 y−1 (Supp. Fig. 1). Over the same time period, alder increased by 83%, covering a total area of 48 km2 in 2018.

Nodule biomass per unit area on the Seward Peninsula and North Slope of Alaska was synthesized and used to fit an allometric relationship between alder height and nodule biomass (Supp. Fig. 2). Based on the allometric relationship between alder height and patch size, we estimate that the increase in cover of tall alders increased root nodule biomass by 41.2 kg y−1. Overall, shrubs expanded nearly 130% in the central Floodplains/Foothills subregion (Supp. Fig. 1c), 84% in the western Coastal subregion (Supp. Fig. 1b), and 34% in the eastern Upland Hillslope subregion (Supp. Fig. 1c), the latter of which was comparable to the 40% increase in tall shrubs identified within the upland Kougarak Hillslope site on the southern boundary of our study domain7.

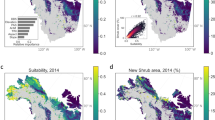

We determined the spatial controls on shrub-patch dynamics using a logistic-form equation and a suite of factors that describe local-to-regional environmental heterogeneity (Table 1). The most important predictor variables (i.e. relative importance, henceforth RI) required to model the probability of tall-shrub expansion based on the likelihood of pixels having new shrub canopies, included permafrost probability (i.e. modeled likelihood of finding near-surface permafrost30), summer air temperature, maximum annual surface temperature, and distance from waterbodies (Figs. 2, 3). We find the correspondence between observed and predicted patterns of shrub-patch expansion was ~87%, in line with our independent model validation accuracy of ~65% across subregions. In addition, we ran a separate model for the expansion of alder alone and found that the highest RI values included permafrost probability, maximum annual surface temperature, air temperature, topographic aspect, and distance from waterbodies (Fig. 2).

Illustrations of the change in shrub canopy extent at selected locations in each subregion (a) and the corresponding climate and environmental drivers included in our shrub model (b). All values in panel (b) are displayed from low (black) to high (white), with the exception of the Upland/Lowland dataset, displayed in gray and black, respectively.

Our identified controls on shrub expansion are not only able to predict fine-scale patterns of shrub cover change across environmentally distinct subregions but are well-supported by our current understanding of shrub dynamics (Figs. 2, 3), highlighting the applicability of our model at scale. Our findings provide quantitative support for previously described relationships between shrub expansion and temperature, soil moisture, topography, and shrub-snow dynamics. For example, enhanced shrub growth is widely reported in passive and forced warming experiments8,22 and other observations14,16, confirming the strong linkage (RI: 0.77) with air temperature in our model. We found that maximum annual surface temperature has a negative relationship with shrub expansion (RI: 0.71), likely due to evaporative cooling in the highly productive wetter floodplain regions31. In fact, many of our modeled drivers are linked to the water content of the soil. For example, the model used the topographic wetness index (TWI), distance from waterbodies, the recency of lake drainage, and a lower likelihood of permafrost presence, all of which are associated with active layer depth and soil water content2,22,30. Previous studies have established that where water availability does not limit plant growth, soil inundation and anoxic conditions may reduce shrub productivity and expansion20,23,25. Our negative relationships with TWI24 (RI: 0.34), distance from waterbodies25 (RI: 0.53), and recency of lake drainage32 (RI: 0.24) illustrate that inundated soils are not conducive to shrub expansion. Demonstrating the relationship between topographic position and shrub expansion, our model found a negative relationship between shrub expansion and elevation (RI: 0.46) and greater expansion in uplands than lowlands (RI: 0.18). These findings align with prior work that found shrubs to perform better on mid-hillslopes23. Finally, our model supports findings that the increased snow packing surrounding tall shrubs insulates the soil and promotes soil decomposition leading to further expansion9, given that shrub expansion increased the later in the year the snow melted (RI: 0.09).

Spatial limits on shrub expansion

In contrast to coarse-scale dispersal models33 unable to resolve fine-scale shrub-patch dynamics, our models find dispersal limitation to only influence local patch infilling, whereas environmental conditions were strong predictors of both locally and regionally heterogeneous patterns of shrub habitat and expansion. Therefore, we attribute the difference in modeled shrub habitat and the present remotely sensed shrub cover (Supp. Fig. 3) to the unrealized niche space of tall deciduous shrubs. This ecological concept describes the geographic space that contains the necessary conditions for the establishment of tall deciduous shrubs but has yet to be occupied34. Given their well-known competitive advantages2,8,10, it is likely shrubs will continue to advance and fill this space. Therefore, our models describe the upper limit or ceiling on the area of potential shrub expansion as defined by the fundamental niche and current environmental conditions. Analysis comparing the environmental conditions of new shrub colonized terrain with that of the overall terrain indicates the characteristics are fundamentally different (Supp. Table 1), further supporting that environmental variables define the range of suitable habitat. The environmental variables found to be most important in our model remained relatively consistent over time, perhaps understandable as we did not consider burned terrain, which have been shown to be hotspots of thermokarst35 and rapid shrub expansion15,36. Therefore, considering two time-periods likely well-represented the gradual patterns of tall-shrub propagation across our study region, however due to limited observation frequencies we were unable to evaluate potential nonlinear change over time. Though biotic interactions other than dispersal are not considered, importantly, these spatial drivers are not static and are projected to change with the climate and environmental conditions35,37,38, thus, so too will the amount and location of suitable tall-shrub habitat.

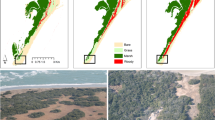

Though we estimate tall shrubs on the central Seward Peninsula of Alaska to currently only occupy ~33% of their present-day fundamental niche space, disturbance processes such as permafrost thaw/degradation and wildfire frequency may further influence local environmental conditions and thus, the distribution of new shrub habitat15. Therefore, we estimate the likely role of such disturbances on 21st-century shrub expansion, by considering three scenarios, (1) shrub expansion will linearly increase with historical rates (i.e. no consideration for wildfire or permafrost degradation), (2) the probability of near-surface permafrost proportionally decreases, expanding the area considered suitable habitat, and (3) shrub-wildfire interactions increase the rate of shrub expansion at burned sites. At current rates of shrub expansion on the central Seward Peninsula (10.3 km2 y−1 within suitable habitat), by the end of the century ~49% of the suitable habitat would be occupied by tall shrubs, but it would take until the year 2377 for tall shrubs to fully realize their niche space. As the climate continues to warm, the permafrost – our most important driver – will continue to degrade beyond a depth of 1 meter by 210039,40. Based on projections of permafrost degradation by the year 210040, if we assume the probability of permafrost degrades by a uniform 10% compared to the current conditions, 1139 km2 of new area becomes suitable habitat for tall shrub species. The area increases another 2391 km2 if permafrost probability decreases by 30%, representing a 62% increase from the current area of suitable habitat (Fig. 4). Due to the well-established impact of tundra fires on the magnitude and rate of shrub recruitment15, by using regionally estimated rates of shrub expansion in response to wildfire15, we estimate the rate of shrub expansion in the central Seward Peninsula to increase 70% to 17.85 km2 y−1, leading to 59% of the suitable shrub habitat being occupied by 2100. These scenarios illustrate the key uncertainties underlying the dynamic ceiling on tundra shrub expansion, where interactions between permafrost thaw and wildfire frequency and severity remain an active research frontier across the tundra biome41,42,43

Modeled suitable habitat for tall deciduous shrubs. Scenarios represent suitable habitat under current permafrost conditions, with a homogeneous decrease in permafrost probability of 10%, and with a homogeneous decrease in permafrost probability of 30%. Inset shows shrub area versus unfilled suitable habitat in three scenarios: the 2018 climate and environmental conditions, the 2100 conditions assuming current expansion rates, and the 2100 conditions including a third of the study area burned with moderate severity between 2018 and 2100. Background image is courtesy of ESRI ArcGIS’s ‘Imagery’ Basemap.

Shrubification and nutrient cycling

Many biological processes in the tundra are nitrogen-limited, which reduces the rate of carbon turnover. Alder shrubs, however, change this dynamic by fixing atmospheric nitrogen in soils, relaxing nutrient limitation and increasing rates of plant productivity and organic matter decomposition7,44,45. Our study occurs in a region with homogeneous warming patterns to control for climatic trends, effectively isolating the important environmental controls underpinning the heterogeneity of tundra shrubification. With edaphic conditions as the only remaining variables, in locations without water limitations, the primary determining factors for shrub expansion were explicitly linked to nutrient availability increasing the rates of productivity and carbon turnover.

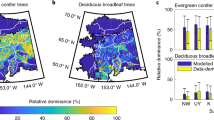

Our analysis describes new ecological interactions between tall-shrub species that propagated overall shrub expansion over multiple decades in northwestern Alaska. Willow-birch expanded on average over four times more in areas with alder (μ = 3889 m2 km−2, n = 1441) than in terrain without alder (μ = 872 m2 km−2, n = 233). This interaction was exemplified by the positive relationship between alder and willow-birch expansion (Fig. 5, Supp. Fig. 4), likely benefiting from the increased nitrogen fertilization (Table 2). Outside of water tracks in water-limited upland regions, new shrub canopies were primarily found in localized patches (Fig. 3. & Supp. Fig. 3) which had lower permafrost probability in our edaphic model and greater amounts of alder than outside the patches. Unfrozen, active soils (i.e. those without permafrost) and those with nitrogen-fixing alder present are both likely to have higher soil nutrient availability than other tundra soils2,7,11. Taken together, the relationship between alder presence and willow-birch expansion, the differential amounts of species-specific expansion, and the environmental conditions in new shrub patches all point towards increased nutrient availability as an important mechanism for shrub expansion in this region, which is consistent with findings for white spruce trees (Picea glauca) in the boreal forest46 and hypotheses generated by leaf litter decomposition experiments in the tundra47.

Illustration of the effects of alder on willow-birch expansion via overlapping histograms of willow-birch expansion area in the absence of alder (red histogram) and in the presence of alder (blue histogram), summarized within 1 km zones (a) and a linear regression between willow-birch expansion and alder expansion for 1 km zones (b). Note the distribution in panel (a) with and without alder indicates increased and decreased willow-birch expansion area, respectively. Point density in panel (b) increases within the heatmap along a cool to warm color gradient. The trendline and 95% confidence interval have been overlaid in black and gray, respectively. Linear regression n = 1261, R2 = 0.2, p < 0.0001.

Current process-based models used to project carbon and nutrient feedbacks to the climate commonly use vegetation categories (e.g. biome, plant community, or plant functional type) to parameterize the important biological processes that drive multiple elemental cycling within Arctic regions48. We show that foreknowledge of functionally important tall-shrub species/genus (i.e. Alnus spp.) may be a readily observable (via remote sensing) precursor for identifying hotspots of elevated nutrient cycling and advanced rates of shrub expansion, creating positive feedbacks to widespread environmental change. Our multi-scale optical remote sensing approach provides a roadmap to readily constrain the spatially heterogeneous patterns of tall-shrub expansion and the ceiling, or upper limit, to the area in which shrubs are able to establish, useful in various field sampling designs, ecological remote sensing, and/or terrestrial and Earth System Modeling applications. Importantly, this dynamic ceiling can be readily updated by future changes in permafrost, climate, and edaphic factors and be reapplied or retrained for other low-Arctic regions for tracking when tall shrubs may fill their fundamental niche space. Improved field observations characterizing nitrogen fixation, mineralization, and assimilation among tall-shrub species, and how these parameters vary across gradients of climate, topography, and moisture, will provide greater mechanistic knowledge describing patterns of shrub expansion across space and time. Our analysis provides evidence to suggest that (i) while shrub expansion will continue to increase in the future, it is a finite process that can be readily constrained with a dynamic ceiling scalable across the pan-Arctic, and (ii) increased nitrogen availability from alder shrubs contributes to a novel, positive feedback that advances overall tall-shrub expansion within northwestern Alaska and beyond.

Methods and Materials

Site selection

Our study region is located within a continuous-discontinuous permafrost region on the central Seward Peninsula of Alaska (Fig. 1a). The Seward Peninsula has an area of approximately 50,000 km2, spanning 400 km from west-to-east. The site selected represents an area of approximately 14,000 km2 with homogeneous regional warming patterns to control for climatic trends, effectively isolating the important environmental controls underpinning the heterogeneity of tundra shrubification. Environmental conditions are variable, ranging in topography from drainage basins below sea level to mountain ranges up to elevations of 1900 m.a.s.l.49, near-surface permafrost from absent to continuous30, average July air temperatures from 1.2 °C to 14.8 °C50, and soil moisture from 0.01 to 0.53 cm3 cm−3 (i.e., volume of water per volume of soil)51. This combination of factors makes the site an ideal area to study the controls on shrub expansion. Within the site, we identified three subregions representing the full range of environmental variation to use for analysis (Fig. 1b-d). Depending on the data source, the long-term annual precipitation in the region varies from 300-500 mm, which is comparable to much of the low-Arctic tundra in Alaska52. Given the relative importance of environmental factors related to water availability (Fig. 2), tundra regions with different precipitation regimes (such as those in the high-Arctic tundra) may respond differently to the same conditions.

Multi-scale tall-shrub mapping

Decadal tall-shrub expansion was estimated using high resolution 1 m spatial resolution declassified 1950 US Navy aerial photographs (project coded SEW00) and 3m-resolution PlanetScope satellite surface reflectance data acquired across our study domain. Historical air photos were downloaded from USGS Earth Explorer (choosing the earliest available dates) and PlanetScope imagery from Planet’s repository (https://www.planet.com). To ensure the compatibility of the two data types (Supp. Fig. 5), we resampled 1 m air photos to 3 m spatial resolution. To create three seamless mosaics of each of our subregions, 210 air photos were processed to remove the border from scanned 229 × 229 mm film, remapped pixel values from all photographs to span the same range53, and ran two low-pass filters to remove widescale illuminance errors caused by camera position54. Processed photographs were orthorectified in Agisoft Metashape and mosaicked using Whitebox Tools to remove seamlines not removed by Metashape. The resulting mosaics for each subregion were georeferenced in ESRI ArcMap to the PlanetScope imagery. In addition, 193 PlanetScope scenes from 2017-18 were used to fully cover our study domain, during both peak-biomass (4-6 of July 2018) and mid-senescent (4-5 of September 2017) phenoperiods. We excluded ~3% of the PlanetScope imagery due to cloud cover.

We performed a supervised classification on each mosaic using visual (R,G,B) and near-infrared (NIR) bands to identify shrub presence or absence. Classification accuracy was evaluated following best practices, i.e. using finer scale observations than the classified imagery55. Therefore, we used high-resolution submeter (0.3 − 0.5 m) resolution WorldView series and GeoEye images acquired between 2014 and 2019 from Maxar/DigitalGlobe to evaluate classification accuracies. We evaluated our shrub classifications using contingency tables using 700 randomly selected points across Planet mosaics. The overall classification accuracy and kappa coefficient (κ) was 97.4% and 0.908, respectively. The user’s and producer’s accuracies for the shrub class were 94.7% and 90%, respectively. Because alder senesces later than birch or willow28, we used the senescent phenoperiod to differentiate alder from willow-birch. In addition to contingency tables derived from regional observations, we qualitatively compared our alder classification to that of local-scale alder mapping at the next-generation ecosystem experiment’s (NGEE–Arctic) Kougarok hillslope site (lat: 65.171006, long:−164.837755), finding 82.5% overlap between alder classifications7.

Similar to others5,29, we next implemented a supervised classification on the 1950 monochrome aerial mosaics. Prior to classification, we masked fires that occurred between 1950 and 2018 to minimize observations of (1) shrub dieback associated with biomass combustion and coincident thermokarst formation15,35, and (2) elevated post-fire rates of shrub recruitment15. In addition, to ensure that dark pixels (i.e. shadows or water) did not cause an overestimation of the 1950 shrub extent, we used the 2018 PlanetScope classification as a maximum boundary of the 1950s shrub classification. This approach assumes areas that were classed as shrub in 1950 but not in 2018 were erroneous due to dark pixels. Thus, this approach represents a conservative estimate of shrub cover expansion. We differenced the two 3 m spatial resolution classifications to create our shrub expansion map. These differences do not necessarily guarantee that entirely new shrub canopy has grown, as small enough shrubs may not have appeared on the aerial imagery, but in most cases, some expansion is likely to have occurred alongside the size increase.

Patch-scale shrub modeling

Gridded data is useful for historical comparisons, using multiresolution datasets, and increasing computational efficiency56. Therefore, to allow us to compare our shrub expansion map to environmental data products, we found the areal proportion of a 15 x 15 m grid that experienced shrub expansion. The fractional cover within these 25-pixel grids were used within our regression analysis. The predictor variable datasets were similarly gridded using the Zonal Statistics function in ArcMap. We aggregated the information from the three subregions into a single dataset that was used for modeling in its entirety.

We selected fifteen predictor variables shown to influence shrub expansion (Table 1). We ran a measure of variance inflation factor (VIF) and found that the variables had low enough covariance to use together (all VIF < 5). Due to the non-normality of the data and the presence of both continuous and factorial predictors, we selected a quasi-logistic regression, as our response variable measured a proportion rather than a binary variable.

We split the data into groups that did and did not experience shrub expansion and then used ten-fold validation (splitting the data into tenths, ensuring each fraction has the same proportion of shrub expansion to non-expansion pixels as the full dataset, and using nine of the groups for training and one for testing the performance) to evaluate the quasi-logistic regression based on the correspondence between the observed and predicted values when run against the testing group. We established a binary presence/absence testing framework, counting any shrub expansion within our observation grids as presence and using a ranked probability cutoff based on observed proportions for predicted shrub expansion, defining expansion as predicted to occur in any pixels above the percentile corresponding to 1.5 times the observed proportion of pixels with shrub expansion (the multiplicative factor added for model uncertainty). To avoid overfitting the data, we used a top-down model selection approach that iteratively removes variables from the models, keeping only those models that improved the correspondence while reducing the number of predictors, then repeating the process iteratively on the new models until no more variables could be removed without reducing the accuracy of the model. We then evaluated the output list of models across the entire set of training data to find the one that best predicted the testing data. We used the varImp function from the R caret package to calculate the importance of each variable and removed any variables that had an importance of less than 5 when the range of values was rescaled from 0 to 100. Equation (1) & (2) give the probabilities of shrub expansion derived from this study. (See Table 1 for variable abbreviations. FUpLow = 1 if Lowland or 1.26 if Upland; FGeol = 1 for undivided surficial deposits, varies from 0.108 to 1.09 for other surficial geologies; P = Probability of shrub expansion.)

This modeling framework was repeated for alder expansion, using a map generated by assuming no change in the dominant species of shrub and considering any 1950 shrub pixels classified as alder in 2018 to also have been alder in 1950, leading to Eq. (3) & (4) with a 93% correspondence between observations and predictions (See Table 1 for variable abbreviations. FUpLow = 1 if Lowland or 2.06 if Upland; FGeol = 1 for undivided surficial deposits, varies from 0.039 to 0.39 for other surficial geologies; P = Probability of alder expansion.).

Environmental variables are often autocorrelated across a landscape, so we investigated whether the data points in our gridded analysis were sufficiently independent. To avoid bias due to spatial autocorrelation, we calculated Moran’s I, but the number of data points made it infeasible in application across our study domain. Therefore, we split the area into 1000 subsets and calculated Moran’s I of the residuals of the model for each, repeating the test 10 times to ensure the splitting was not affecting the results. The results were statistically significant but small (range 0.02–0.04). There is a known issue of reduced p-values with large sample sizes57, such as our n of 600,000 per group, and spatial autocorrelation effects increase as the magnitude of Moran’s I moves farther from zero58. Our values were very near zero, indicating limited autocorrelation, so we concluded that the points were sufficiently independent. To ensure the size of the split was not artificially lowering autocorrelation values, we repeated the process with groups twice as large and found that residual Moran’s I decreased with increasing numbers of data points per group, suggesting that it would further approach 0 with the entire dataset.

Using environmental predictors, we expanded the model from the subregions to the entire study area. We used 10 additional 1950 images for use in an independent validation of the model results and processed them using the 1950 aerial image protocols previously described (Supp. Fig. 6). The images were selected to maximize the representation of spatial heterogeneity across our study region (Fig. 1a). The same classification protocols (described above) were applied to these aerial photographs and a shrub change product was generated for each. We found the model to have an accuracy of 65%, indicating that if we applied the same model to an independent dataset, it will correctly predict the presence or absence of shrub expansion in 65% of the area.

To determine the influence of dispersal limitation on our shrub extent model output (only used edaphic predictors), we tested whether shrubs failed to expand across our study domain due to limits on propagation rather than environmental factors. We added an omnidirectional minimum distance from existing shrub canopy metric by using the Google Earth Engine distance function on the 1950 classification, which served as a proxy for dispersal limitation, as seed propagation decreases with distance33. Although this simplified approach was necessary to contextualize the relative importance of our results, understandably, it does not account for the complexities of shrub-specific sexual or asexual reproduction that can modify the spatial patterns of dispersal limitation that varies with environmental conditions59. The new model considering dispersal outperformed our edaphic parameter model at very fine scales (Supp. Fig. 3), typically at the edges of patches or where infilling occurred, but in areas where completely new shrub canopy grew the environmental model corresponded better with observed expansion. This indicates that while dispersal is important for determining exactly how shrub patches will respond at local scales as patches become more fragmented at their edges, it does not play a major role in where new patches may establish, which is controlled by climate and environmental conditions (Fig. 2).

Statistics and Scenarios

To verify that the predicted suitable habitat was characteristically distinct from the overall study domain, we ran a Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test for each of the continuous variables present in the model, both within and outside the suitable habitat (Supp. Table 1). We found the maximum difference in the cumulative distribution functions, which indicates the degree of divergence of the values of each variable between the full study area and the suitable habitat. Because of the relatively low area of drained lakes to the land surface, we repeated the test for recency of lake drainage while excluding land area. For the categorical variables, which cannot be evaluated by Kolmogorov-Smirnoff testing, we compared the proportion of the data that fell into each category for both sets of data.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine how changing environmental conditions over time would impact our calculated suitable habitat. Our baseline scenario was the 2018 map of suitable habitat as determined by our edaphic model. For our second scenario, we evaluated the effects of wildfire on shrub expansion. We calculated that one-third of the land area burned over the course of our study period using fire maps from the Alaska Interagency Coordination Center (https://fire.ak.blm.gov/) then we assumed that another third would burn by the century’s end and that low and high severity fires average out to moderate severity, letting us use the rates from Chen & Lara (2021) to calculate the rate of shrub expansion with wildfire as 17.85 km2 y−1. Our final scenarios evaluated the effects of changing permafrost by rerunning the shrub expansion model once with the permafrost probability reduced by a flat 10% and once with a flat 30% reduction and calculating the new amount of suitable habitat in these scenarios (Fig. 4).

Species-specific interactions and upscaling nitrogen data

Because of the unique influence alder has on soil nitrogen, we examined the impacts of expanding alder canopies on root nodule biomass. We used all available data on alder nodule biomass, collected from extensive field surveys in logistically challenging tundra environments in Alaska. Root nodule data were collected via soil cores in 2017 at the NGEE Arctic Kougarok Hillslope study site (Fig. 1a) and along the Dalton Highway within the Brooks Range and Foothills of the Brooks Range. See the published datasets60,61 for the full methodology. Due to different collection methods (i.e. different size plots, different size cores, and different sampling depths), the nodule biomass data was standardized by the total sampling effort at each plot. We used the proportion of the plot’s total soil volume that was sampled to represent the measurement effort irrespective the collection methods. The strongest correlation with nodule biomass was found between the effort-standardized biomass per unit area and the maximum height of the alder shrub (Eq. (5), R2 = 0.2115, p = 0.014; Brn = Root nodule biomass, h = height). Therefore, we used this relationship for upscaling from UAS to shrub classifications.

We leveraged 5 cm very high spatial resolution UAS RGB imagery and canopy height models (CHMs) from the NGEE Arctic Kougarok Hillslope study site (located within the central Floodplains/Hillslope subregion) acquired in 201962 to estimate area-height relationships. The CHMs were computed using structure-for-motion photogrammetric techniques63. We used UAS RGB imagery to visually delineate all alder individuals within four 10 × 10 Planet pixel grids which varied in alder cover (Supp. Fig. 6). We used this data to calculate alder density and area within each PlanetScope pixel, resulting in an average density of 2.336 individuals per pixel in pixels classed as alder. Based on these calculations, we computed an allometric relationship between aerial alder cover and maximum alder height (Eq. (6), R2 = 0.612, p < 0.001; h = height, AA = aerial area).

To relate that back to our full study site, we used this estimate of alder patch cover in our study region and divided it by the average density of 2.336 per pixel to calculate the number of individual alder shrubs that occupy each pixel, which we used with Eq. 5 to find the average maximum height of alder shrubs. We estimated nodule biomass per unit area using estimated height to determine the total nodule biomass in 1950 and 2018.

Data availability

All sources of environmental data used in the habitat suitability model can be found in Table 1 with appropriate accession citations. The root nodule biomass datasets can be found via public repositories at https://doi.org/10.5440/1493669 and https://doi.org/10.15485/1631262. UAS and CHM data are available via the NGEE-Arctic repository at https://doi.org/10.5440/1906348. Shrub classifications and model results are archived at the Arctic Data Center and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.18739/A28911S58.

Code availability

R and Google Earth Engine code used in the analysis may be provided by Aiden I. G. Schore upon request. See provided correspondence details.

References

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 1–10 (2022).

Mekonnen, Z. A. et al. Arctic tundra shrubification: a review of mechanisms and impacts on ecosystem carbon balance. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 053001 (2021).

Myers-Smith, I. H. et al. Complexity revealed in the greening of the Arctic. Nat. Clim. Chan. 10, 106–117 (2020).

Heijmans, M. M. P. D. et al. Tundra vegetation change and impacts on permafrost. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 68–84 (2022).

Tape, K., Sturm, M. & Racine, C. The evidence for shrub expansion in Northern Alaska and the Pan-Arctic. Glob. Chang. Biol 12, 686–702 (2006).

Myers-Smith, I. H. et al. Shrub expansion in tundra ecosystems: Dynamics, impacts and research priorities. Environ. Res. Lett. 6, 045509 (2011).

Salmon, V. G. et al. Alder Distribution and Expansion Across a Tundra Hillslope: Implications for Local N Cycling. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1099 (2019).

Elmendorf, S. C. et al. Global assessment of experimental climate warming on tundra vegetation: Heterogeneity over space and time. Ecol. Lett. 15, 164–175 (2012).

Sturm, M. et al. Snow–Shrub Interactions in Arctic Tundra: A Hypothesis with Climatic Implications. J. Clim. 14, 336–344 (2001).

Martin, A. C., Jeffers, E. S., Petrokofsky, G., Myers-Smith, I. & MacIas-Fauria, M. Shrub growth and expansion in the Arctic tundra: an assessment of controlling factors using an evidence-based approach. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 085007 (2017).

Callahan, M. K. et al. Nitrogen Subsidies from Hillslope Alder Stands to Streamside Wetlands and Headwater Streams, Kenai Peninsula, Alaska. JAWRA J. Am. Water Res. Associat. 53, 478–492 (2017).

Frost, G. et al. 2022: Tundra greenness [in “State of the Climate in 2021”]. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 103, S291–S293 (2022).

Frost, G. V. et al. Tundra Greenness. in Arctic Report Card 2022 (eds. Druckenmiller, M. L., Thoman, R. L. & Moon, T. A.) (2022). https://doi.org/10.25923/G8W3-6V31.

Berner, L. T., Jantz, P., Tape, K. D. & Goetz, S. J. Tundra plant above-ground biomass and shrub dominance mapped across the North Slope of Alaska. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 035002 (2018).

Chen, Y., Hu, F. S. & Lara, M. J. Divergent shrub-cover responses driven by climate, wildfire, and permafrost interactions in Arctic tundra ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 27, 652–663 (2021).

Andreu-Hayles, L. et al. A narrow window of summer temperatures associated with shrub growth in Arctic Alaska. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 105012 (2020).

Davis, E. L., Trant, A. J., Way, R. G., Hermanutz, L. & Whitaker, D. Rapid ecosystem change at the southern limit of the canadian arctic, torngat mountains national park. Remote Sens (Basel) 13, 2085 (2021).

Myers-Smith, I. H. et al. Eighteen years of ecological monitoring reveals multiple lines of evidence for tundra vegetation change. Ecol. Monogr. 89, e01351 (2019).

Liu, C., Huang, H. & Sun, F. A Pixel-Based Vegetation Greenness Trend Analysis over the Russian Tundra with All Available Landsat Data from 1984 to 2018. Remote Sens. 13, 4933 (2021).

Magnússon, R. Í. et al. Shrub decline and expansion of wetland vegetation revealed by very high resolution land cover change detection in the Siberian lowland tundra. Sci. Total Environ. 782, 146877 (2021).

Aalto, J., Niittynen, P., Riihimäki, H. & Luoto, M. Cryogenic land surface processes shape vegetation biomass patterns in northern European tundra. Commun. Earth Environ 2, 1–10 (2021).

Scharn, R. et al. Vegetation responses to 26 years of warming at Latnjajaure Field Station, northern Sweden. Arct Sci 8, 858–877 (2022).

Mekonnen, Z. A. et al. Topographical Controls on Hillslope-Scale Hydrology Drive Shrub Distributions on the Seward Peninsula, Alaska. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 126, e2020JG005823 (2021).

Naito, A. T. & Cairns, D. M. Relationships between Arctic shrub dynamics and topographically derived hydrologic characteristics. Environ. Res. Lett. 6, 045506 (2011).

Liljedahl, A. K., Timling, I., Frost, G. V. & Daanen, R. P. Arctic riparian shrub expansion indicates a shift from streams gaining water to those that lose flow. Commun. Earth Environ 1, 1–9 (2020).

Elmendorf, S. C. et al. Plot-scale evidence of tundra vegetation change and links to recent summer warming. Nat. Clim. Chan. 2, 453–457 (2012).

Macander, M. J. et al. Time-series maps reveal widespread change in plant functional type cover across Arctic and boreal Alaska and Yukon. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 054042 (2022).

Koike, T. 16 - Autumn Coloration, Carbon Acquisition and Leaf Senescence. in Plant Cell Death Processes (ed. Noodén, L. D.) 245–258 (Academic Press, 2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012520915-1/50019-9.

Tape, K. D., Hallinger, M., Welker, J. M. & Ruess, R. W. Landscape Heterogeneity of Shrub Expansion in Arctic Alaska. Ecosystems 15, 711–724 (2012).

Pastick, N. J. et al. Distribution of near-surface permafrost in Alaska: Estimates of present and future conditions. Remote Sens Environ 168, 301–315 (2015).

Zwieback, S. et al. Improving Permafrost Modeling by Assimilating Remotely Sensed Soil Moisture. Water Resour. Res. 55, 1814–1832 (2019).

Ludden, C., Chen, W. & Lara, M. J. Patterns of Vegetation Succession Following Lake Drainage in Northern Alaska. in Abstract GC25G-0761 presented at 2022 AGU Fall Meeting, 12–16 Dec. (2022). https://agu.confex.com/agu/fm22/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/1121659.

Liu, Y. et al. Dispersal and fire limit Arctic shrub expansion. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–10 (2022).

Soberón, J. & Nakamura, M. Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 19644–19650 (2009).

Chen, Y., Lara, M. J., Jones, B. M., Frost, G. V. & Hu, F. S. Thermokarst acceleration in Arctic tundra driven by climate change and fire disturbance. One Earth 4, 1718–1729 (2021).

Racine, C., Jandt, R., Meyers, C. & Dennis, J. Tundra Fire and Vegetation Change along a Hillslope on the Seward Peninsula, Alaska, USA. Arct. Antarct Alp Res. 36, 1–10 (2004).

Bruhwiler, L., Parmentier, F. J. W., Crill, P., Leonard, M. & Palmer, P. I. The Arctic Carbon Cycle and Its Response to Changing Climate. Curr. Clim. Chan. Rep. 7, 14–34 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Resilience and sensitivity of ecosystem carbon stocks to fire-regime change in Alaskan tundra. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 151482 (2022).

Walvoord, M. A. & Striegl, R. G. Complex Vulnerabilities of the Water and Aquatic Carbon Cycles to Permafrost Thaw. Front. Clim. 3, 730402 www.frontiersin.org (2021).

Koven, C. D. et al. Permafrost carbon-climate feedbacks accelerate global warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14769–14774 (2011).

McCarty, J. L. et al. Reviews and syntheses: Arctic fire regimes and emissions in the 21st century. Biogeosciences 18, 5053–5083 (2021).

Johnstone, J. F. et al. Factors shaping alternate successional trajectories in burned black spruce forests of Alaska. Ecosphere 11, e03129 (2020).

Walker, X. J. et al. Increasing wildfires threaten historic carbon sink of boreal forest soils. Nature 572, 520–523 (2019).

Kou-Giesbrecht, S. & Menge, D. Nitrogen-fixing trees could exacerbate climate change under elevated nitrogen deposition. Nat Commun 10, 1493 (2019).

Ramm, E. et al. A review of the importance of mineral nitrogen cycling in the plant-soil-microbe system of permafrost-affected soils—changing the paradigm. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 013004 (2022).

Sullivan, P. F., Ellison, S. B. Z., McNown, R. W., Brownlee, A. H. & Sveinbjörnsson, B. Evidence of soil nutrient availability as the proximate constraint on growth of treeline trees in northwest Alaska. Ecology 96, 716–727 (2015).

Demarco, J., Mack, M. C. & Bret-Harte, M. S. Effects of arctic shrub expansion on biophysical vs. biogeochemical drivers of litter decomposition. Ecology 95, 1861–1875 (2014).

Pastick, N. J. et al. Spatiotemporal remote sensing of ecosystem change and causation across Alaska. Glob. Chang. Biol 25, 1171–1189 (2019).

Porter, C. et al. ArcticDEM, Version 3. Harvard Dataverse, V1 https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OHHUKH (2018).

Walsh, J. E. et al. Downscaling of climate model output for Alaskan stakeholders. Environ. Model. Software 110, 38–51 (2018).

Kim, S. et al. SMAP L3 Radar Global Daily 3 km EASE-Grid Soil Moisture. Version 3. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.5067/IGQNPB6183ZX (2016).

Newman, A. J., Clark, M. P., Wood, A. W. & Arnold, J. R. Probabilistic Spatial Meteorological Estimates for Alaska and the Yukon. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmosph. 125, e2020JD032696 (2020).

Hast, A. & Marchetti, A. Retrospective Illumination Correction of Greyscale Historical Aerial Photos. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 6979 LNCS, 275–284 (2011).

Zhu, J., Liu, B. & Schwartz, S. C. General Illumination Correction And Its Application To Face Normalization https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2003.1199125 (2003).

Olofsson, P. et al. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens Environ 148, 42–57 (2014).

Walton, D. & Hall, A. An Assessment of High-Resolution Gridded Temperature Datasets over California. J Clim 31, 3789–3810 (2018).

Gómez-de-Mariscal, E. et al. Use of the p-values as a size-dependent function to address practical differences when analyzing large datasets. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–13 (2021).

Dormann, C. F. et al. Methods to account for spatial autocorrelation in the analysis of species distributional data: a review. Ecography 30, 609–628 (2007).

Douhovnikoff, V. et al. Clonal Diversity in an Expanding Community of Arctic Salix spp. and a Model for Recruitment Modes of Arctic Plants. Arct Antarct Alp Res 42, 406–411 (2010).

Salmon, V. & Iversen, C. NGEE Arctic Plant Traits: Nodule Biomass, Kougarok Road Mile Marker 64, Seward Peninsula, Alaska, 2017. Next Generat. Ecosyst. Exp. Arctic Data Collect. https://doi.org/10.5440/1493669 (2019).

Fraterrigo, J. & Chen, W. Arctic shrub root traits, northern Alaska, summer 2017 (Version 2.0). Arctic Shrub Expansion, Plant Functional Trait Variation, and Effects on Belowground Carbon Cycling. ESS-DIVE Reposit. https://doi.org/10.15485/1631262 (2023).

Yang, D., Hanston, W., Hayes, D. & Serbin, S. UAS remote sensing (DJI Phantom 4 RTK platform): RGB orthomosaic, digital surface and canopy height models, plant functional type map, Seward Peninsula, Alaska, 2019. Next Generat. Ecosyst. Exp. Arctic Data Collect. https://doi.org/10.5440/1906348 (2022).

Yang, D. et al. Integrating very-high-resolution UAS data and airborne imaging spectroscopy to map the fractional composition of Arctic plant functional types in Western Alaska. Remote Sens Environ 286, 113430 (2023).

Cook, M., Schott, J. R., Mandel, J. & Raqueno, N. Development of an Operational Calibration Methodology for the Landsat Thermal Data Archive and Initial Testing of the Atmospheric Compensation Component of a Land Surface Temperature (LST) Product from the Archive. Remote Sens (Basel) 6, 11244–11266 (2014).

Jorgenson, M. T., Marcot, B. G., Swanson, D. K., Jorgenson, J. C. & DeGange, A. R. Projected changes in diverse ecosystems from climate warming and biophysical drivers in northwest Alaska. Clim Change 130, 131–144 (2015).

Pekel, J. F., Cottam, A., Gorelick, N. & Belward, A. S. High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 540, 418–422 (2016).

Lara, M. J., Chen, Y. & Jones, B. M. Recent warming reverses forty-year decline in catastrophic lake drainage and hastens gradual lake drainage across northern Alaska. Environ. Res. Lett 16, 124019 (2021).

Safanelli, J. L. et al. Terrain Analysis in Google Earth Engine: A Method Adapted for High-Performance Global-Scale Analysis. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inform. 9, 400 (2020).

Sørensen, R., Zinko, U. & Seibert, J. On the calculation of the topographic wetness index: evaluation of different methods based on field observations. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 10, 101–112 (2006).

Tape, K. D., Lord, R., Marshall, H.-P. & Ruess, R. W. Snow-Mediated Ptarmigan Browsing and Shrub Expansion in Arctic Alaska. Ecoscience 17, 186–193 (2010).

Macander M. J. & Swingley C. S. Mapping Snow Persistence for the Range of the Western Arctic Caribou Herd, Northwest Alaska,Using the Landsat Archive (1985–2011). https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2191504 (2012).

Frost, G. V., Epstein, H. E., Walker, D. A., Matyshak, G. & Ermokhina, K. Patterned-ground facilitates shrub expansion in Low Arctic tundra. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 015035 (2013).

Till, A. B. et al. Preliminary Integrated Geologic Map Databases for the United States. https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2009/1254/database/SPindex.htm (2009).

Terskaia, A., Dial, R. J. & Sullivan, P. F. Pathways of tundra encroachment by trees and tall shrubs in the western Brooks Range of Alaska. Ecography 43, 769–778 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation’s Environmental Engineering Program (EnvE-1928048 to MJL) and the Department of Energy’s Biological and Environmental Research Program (DE-SC0021094 to JMF and MJL). VGS is supported by the NGEE Arctic project which is funded through the US Department of Energy’s Biological and Environmental Research Program. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Geospatial support for this work provided by the Polar Geospatial Center under NSF-OPP awards 1043681 and 1559691. Portions of this document include intellectual property of Esri and its licensors and are used under license. Copyright © 2023 Esri and its licensors. All rights reserved.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.I.G.S. was involved in conceptualization, analysis, writing, figure creation, and manuscript editing. J.M.F. provided data and assisted in funding acquisition and manuscript editing. V.G.S. provided data and assisted in manuscript editing. D.Y. provided data and assisted in manuscript editing. M.J.L. was involved in conceptualization, manuscript editing, funding acquisition, and project supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Katherine Dearborn and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kate Buckeridge and Aliénor Lavergne. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schore, A.I.G., Fraterrigo, J.M., Salmon, V.G. et al. Nitrogen fixing shrubs advance the pace of tall-shrub expansion in low-Arctic tundra. Commun Earth Environ 4, 421 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01098-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01098-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.