Abstract

The energy transition is progressing slowly in the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). To achieve ASEAN’s target of 23% renewables in the primary energy supply by 2025, the region would need to invest USD 27 billion in renewable energy every year. However, the ASEAN countries attracted no more than USD 8 billion annually from 2016 to 2021. Through a comparative review of three key factors for attracting investment—renewable energy legislation, energy governance reform, and general conditions for investors—this study examines why the region’s renewable energy sector has not attracted more capital. The contribution of the article is threefold. First, it develops a new review model for assessing the business climate for renewable energy in any country. Second, it offers an update on the state of renewable energy deployment in the ASEAN countries. Third, taking into account international best practices, it identifies the obstacles and solutions to attracting investment in renewable energy in Southeast Asia. The article finds that carbon lock-in is pervasive, regulatory practices have been copy-pasted from the fossil-fuel sector to the renewables sector, and, except for Malaysia and Vietnam, no ASEAN country has implemented a major pro-renewable energy governance reform. Certain advanced renewable energy measures, such as auctions and feed-in tariffs, have been adopted in some member states, but the institutional capacity to implement them is limited. The share of renewables in the energy governance system needs to be increased.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

As of June 2022, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was the fifth-largest economy in the world. In 2019, the combined GDP of the ten ASEAN countries amounted to USD 3.2 trillion (ASEAN 2021). Given the region’s young population—more than 60% Southeast Asians are under the age of 35—ASEAN is set to become the world’s fourth-largest economy by 2030.

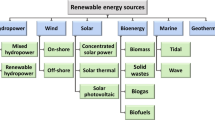

The ASEAN countries rely heavily on fossil fuels for their economic and industrial development: fossil fuels accounted for more than 75% of the region’s energy mix in 2019, while the share of renewables was only 14% (Liu and Noor 2020; ACE 2022). However, already in 1986 ASEAN signed its first agreement to cooperate on renewable energy (ASEAN 2020). For decades, hydropower has been the region’s main source of renewable energy, whereas solar and wind power have been underutilized (IEA 2019). Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam depend heavily on hydropower for electricity generation.

In 2015, ASEAN agreed to increase the share of solar, wind, and hydropower in the energy mix from 9% in 2014 to 23% in 2025 (IRENA & ACE 2016). Although this target had the modifier “aspirational” tacked on to it, each of the ten member states established additional targets at the national level, and governments across the region started making positive statements about renewable energy. During the period 2015–2021, Vietnam was considered a regional renewable energy success story (Vakulchuk et al. 2020a; Do et al. 2021). Also Malaysia made headlines in 2019, when it announced that it aimed to attract USD 8 billion in private investment to increase the share of renewables in the energy mix to 20% by 2025. This investment was expected to create 100,000 jobs and help the country fulfill its nationally determined contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement (GreenTech Malaysia 2019).

ASEAN has been one of the most attractive global investment destinations since 2015. Total foreign direct investment (FDI) in ASEAN rose from an annual average of USD 37 billion in 2015–2017 to USD 74 billion in 2018–2020 (Lee and Adam 2022). By 2020, the official renewable energy policies of the ASEAN countries were already more favorable than those of most other regions of the world (IEA 2019). Despite these developments, and despite the falling costs of renewable energy globally, the region has one of the world’s slowest development rates for renewables, both in terms of investment attracted to the sector and electricity generation capacity (Razzouk 2018; Daubach 2019) (see Appendix). To reach the 23% target, ASEAN would need to attract investment of USD 27 billion in renewable energy generation and infrastructure every year from 2016 to 2025—a total of USD 290 billion, or 1% of the region’s GDP (IRENA & ACE 2016).

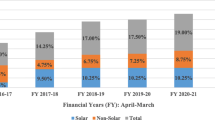

However, investments in 2018 totaled only USD 7 billion, just 25% of the amount required. Such limited investment in renewables will make it difficult to reach ASEAN’s target of 23% renewables by 2025. In some years, investment growth has been slow, stagnant or even decreasing in some ASEAN member states (see Fig. 1). Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand experienced negative investment trends from 2017 to 2018. Investment in renewables in Indonesia was only USD 0.8 billion in 2018, a drop from USD 1 billion in 2017 (VOA 2018; Frankfurt School-UNEP Centre/BNEF 2019). In 2019, Ignasius Jonan, the Indonesian Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources, recognizing that the country was struggling to attract investment in renewables, stated that he was pessimistic that the 23% target would be met by 2025 (VOA 2018). Several scholars note that ASEAN’s nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement are unambitious and the region is unlikely to reach its 23% renewable energy target (Overland et al. 2021). To achieve that target, the region will need to compete successfully against the many other parts of the world vying to attract renewable energy investment. It is therefore imperative to improve the business climate for renewable energy.

This article asks: (1) Why, despite the positive rhetoric, has ASEAN largely failed to attract significant investment in renewable energy since the signing of the Paris Agreement? (2) How can renewable energy governance and the business climate be improved?

2 Methodology

Our three-step methodological approach draws on previous studies of the attractiveness of the business climate for renewable energy (Polzin et al. 2015; Vakulchuk et al. 2017; REN21 2019). First, we develop a new review model (see Fig. 2). Second, using the model, we trace ASEAN’s progress in attracting investment in renewables from 2016 to 2022. We compare the ten ASEAN countries with each other, and review renewable energy legislation, energy governance reform, and investment conditions in the ASEAN countries. These three areas are major determinants of the ability to attract renewable energy investment. For instance, a long-term strategic planning framework and robust regulatory regime for renewables can help attract institutional investors (Polzin et al. 2015). The third and final step in our approach is to review international best practices and discuss their applicability to ASEAN.

Understanding the business climate is important because investment is the main indicator of future growth in renewable energy (Vakulchuk et al. 2017). Moreover, FDI in renewable energy has positive spill-over effects in other areas, such as employment, local air pollution, and CO2 reduction (Mahesh and Shoba Jasmin 2013; Dvořák et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2017; Djellouli et al. 2022).

We review the academic literature on renewable energy in the ASEAN region from 2010 to 2022. Relevant publications were identified using Crossref, Dimensions, Google Scholar, ISI Web of Science, and Scopus. We used the following search string: “ASEAN” AND (“renewable energy” OR “solar energy” OR “hydropower” OR “wind energy” OR “clean energy” OR “clean electricity” OR “business climate” OR “decarbonization”).

We also review the regulatory frameworks, legal and policy documents, and reports of each ASEAN country. First, we assess the adoption and enforcement of renewable energy legislation and best policy practices, including regulatory policies, fiscal incentives, and public financing mechanisms. We draw on the classification of best regulatory and fiscal practices for renewable energy promotion of REN21, the World Bank’s Regulatory Indicators for Sustainable Energy (RISE) Index and the database of the ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE).

We review the energy governance system and reform measures, or lack thereof, for governing renewable energy. We map energy governance bodies to identify the weight accorded to renewables in the governance systems of the ASEAN countries. In many developing countries (and often in developed ones), the government organizations traditionally responsible for fossil fuels are now tasked with regulating renewable energy. This may be unknown territory for them and be seen as a burden. Governing renewable energy is different from governing the production of fossil fuels due to the variety of renewable energy sources, their decentralized nature, and regulatory and market complexity (Wiseman 2011; Reusswig et al. 2018).

We examine whether the ASEAN countries, like many other states, are subject to institutional carbon lock-in (Unruh 2000, 2002). Their institutions are decades old and were established to govern the fossil-fuel industry. Carbon lock-in has been defined as a “self-perpetuating inability to change from existing carbon-intensive activities and technologies to less carbon-based activities and technologies” (Rentier et al. 2019, p. 620). It is part of the broader concept of institutional resistance to change in the form of reforms, whether incremental or abrupt (North 1990; Agócs 1997). There can be formidable internal bureaucratic resistance and low prioritization of renewable energy in the government. However, the lock-in effect is not specific to ASEAN. Also EU countries such as Germany and Poland suffer from carbon lock-in as they struggle to phase out coal (Rentier et al. 2019).

Finally, we review the business climate for renewable energy in the ASEAN member states using two international rankings relevant for assessing renewable energy performance: the World Bank’s RISE Index and Ernst & Young’s Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index (RECAI).

Several caveats and limitations of this study should be noted. First, we focus primarily on macro-level (central government) challenges related to renewable energy governance in the ASEAN countries. Micro-level (regional, district) governance barriers are beyond the scope of the present study. Second, we recognize that different types of renewable energy require different investment strategies (Boomsma et al. 2012; Cicea et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2022). In our study, however, we do not distinguish between investment in different types of renewable energy, and examine renewable energy investment flows in ASEAN at the aggregate level.

3 Lack of research on the business climate for renewables in ASEAN

The technical aspects of ASEAN’s energy transition have received considerable scholarly attention. The focus has been on formal mechanisms, economic modeling, and technology (see Table 1). By contrast, the business climate, renewable energy governance, legislation, and policy have received much less attention in the academic literature on renewable energy in ASEAN. Although these topics are often touched upon indirectly, few studies have discussed renewable energy policy implementation and governance in depth (Yatim et al. 2016; Huang et al. 2019; Khuong et al. 2019; Marquardt 2014; Vakulchuk et al. 2020b,c; Phoumin et al. 2021; Nepal et al. 2021).

Such policy-oriented literature mainly discusses barriers to renewable energy adoption. Major obstacles here have included fossil-fuel subsidies, lack of public awareness/support, limited technical capacity to govern renewables, political barriers in energy policy coordination, lack of institutional infrastructure, financial hurdles, and immature markets (Forsyth 1999; Karki et al. 2005; Sovacool 2010; Marquardt 2014; Chang and Li 2015; Pratiwi and Juerges 2020). Other scholars note that the ASEAN member states lack governance capacity, but could join the IEA, IRENA, and other international organizations to strengthen this (Vakulchuk et al. 2020a, d). On the whole, the policy-oriented and technical academic literature fails to comprehensively review the progress made by the ASEAN countries in attracting investment in renewable energy and in reforming their renewable energy governance since 2015. The present study aims to fill this gap.

4 Results

4.1 Renewable energy legislation in the ASEAN member states

By 2022, most of the ASEAN countries had adopted renewable energy regulations based on best practices in other parts of the world. Extensive information on renewable energy legislation in each country is provided by international organizations (IRENA & ACE 2016; IRENA 2017, 2018; IEA 2019; NREL 2019; REN21 2019; ACE 2020). Table 2 presents a checklist of 14 best practices for regulatory policies and financial incentives for renewable energy, showing which of these policies each country has adopted.

All the ASEAN countries have official renewable energy targets. However, there is no regional- or district-level allocation of targets within each country. Targets apply to the entire country and do not take into account variations in renewable energy potential, geography, available infrastructure, availability of technology, or grid connectivity. This lack of detail is particularly problematic in a large country such as Indonesia, extending over 5000 km from one end to another and with a population of over 260 million. The EU represents a successful case of harmonization of national and local targets: ASEAN could take inspiration from the EU in this area (Khuong et al. 2019).

Except for Cambodia, all the ASEAN countries have included renewable energy in their nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement. The five top ASEAN performers adopted most of the possible policy measures, and there has been progress across the region.

Table 3 shows the scores of the ASEAN countries on the World Bank’s RISE Index. Indicators 1–4 cover the legal side of the regulatory framework for renewables, where the ASEAN countries have clearly achieved much. However, scores on the more technical indicator 5 (network connection and use) are low. Indicator 7 (carbon pricing and monitoring measures), which concerns implementation and enforcement policy, is lacking for every country except Cambodia and Indonesia. Despite these limitations, most ASEAN countries now have much of the necessary legislation in place or are close to adopting it.

One reason why the ASEAN member states have adopted forward-looking renewable energy legislation and policies is that most of them receive assistance from international organizations and donors, which often provide advice and help in designing regulatory measures. For instance, the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, and others have assisted the region in drawing up hydropower policies over several decades now (Bakker 1999), and, more recently, climate mitigation policies (Zimmer et al. 2015). Moreover, evidence indicates that public agencies and big donors, such as the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, have been instrumental in providing investment in renewables in the ASEAN countries, whereas private international investors are yet to invest in solar and wind on a large scale (IEA 2019).

Although Indonesia is among the ASEAN leaders in terms of policies adopted, as mentioned above, it experienced a decline in renewable energy investment from 2017 to 2018 (see Fig. 1). Why has there not been more investment in Indonesia if much of the legislation is already in place? The main reason is weak implementation and enforcement of the regulatory policies and fiscal incentives due to weak governance and institutions (see Sect. 4.2). The enabling policies across the ASEAN countries are weak or non-existent (Khuong et al. 2019; Erdiwansyah et al. 2019). Often, investors do not consider the legislation that has been adopted to be a sufficient basis for investing and put greater emphasis on whether there are institutions capable of implementing the legislation effectively and consistently.

If legislation is weakly implemented, attracting investors can be challenging, even when costs fall to levels that should in principle be attractive. In 2018, Singapore’s Energy Market Authority stressed that improving the bankability of projects needed to be the priority for ASEAN investment policy (Energy Market Authority 2018). The counterparty risk indicator in Table 3—which includes creditworthiness, payment risk mitigation, utility transparency, and monitoring—shows that there has been more progress in bankability than in other dimensions, and that ASEAN is becoming more competitive cost-wise. Still, investors are reluctant to invest in the region because the policy commitment and long-term reform trajectory appear uncertain. Moreover, the cost of renewables is falling rapidly in other parts of the world, too. Thus, progress on bankability is not a comparative advantage for ASEAN in the global context.

4.2 Governance structure for renewable energy

In this section, we take a detailed look at renewable energy governance structures in the ASEAN countries. As of 2022, with the partial exception of hydropower, the ASEAN member states view renewables as only a complement to other energy sources. This is also reflected in their governance structures.

Table 4 shows which government agencies oversee renewable energy policies in the ASEAN member states. In 2020, Malaysia established an energy ministry with both “environment” and “climate change” in its title. However, no energy ministry in the nine other countries has “renewable energy” or “climate change” in its institutional name, and renewables are not prioritized at the ministerial level. Renewable energy policy is assigned to one or more smaller subunits that have limited autonomy and decision-making power, lack required personnel, and have limited resources at their disposal.

Perhaps due to inertia, or limited resources and capacity, regulations governing fossil fuels are often copy-pasted into the renewables sector in the ASEAN countries. However, transitioning to renewable energy is more difficult if decision-makers use existing fossil fuel-based institutions to govern renewable energy, because the regulatory logic of renewables differs from that of fossil fuels (Wiseman 2011).

Vietnam faces governance challenges relating to renewable energy, including fragmented coordination of the sector (Zimmer et al. 2015). Nevertheless, its Ministry of Industry and Trade is gradually becoming a more renewables-oriented institution, as it has broadened the functional responsibility of the Department of New and Renewable Energy. Compared to the other ASEAN member states, Vietnam is also widely perceived as a proactive reformer that has one of the most advanced feed-in tariff policies in the region (Do et al. 2021). As a result, many new investors entered the Vietnamese renewable energy market in 2020–2021.

Limited capacity to govern renewable energy projects is a significant barrier to investment in Malaysia. Renewable energy policy and governance remain incoherent and weak (Yatim et al. 2016). This is also reflected in the limited power and scope of the responsibilities of the Sustainable Energy Development Authority, which is part of the Ministry of Energy, Science, Technology, Environment and Climate Change. Government energy policy in Indonesia has been criticized for not dealing with the challenges related to poor development of renewable energy (VOA 2018).

The Philippines government adopted the Renewable Energy Act in 2008 but failed to promote reform of the renewable energy industry. The sector is poorly coordinated and highly fragmented; resistance to renewables is pervasive due to power struggles between central, provincial, and municipal governments; these struggles in turn hold back “the enforcement of a comprehensive policy framework for renewables” (Marquardt 2017, p. 19).

In 2013, Thailand initiated reform of the renewables sector as part of its Alternative Energy Development Plan for the period 2015–2036. However, the country has “no mechanism to ensure that the targets are met and that relevant agencies in the public sector undertake their responsibilities in the most effective manner” (Khuong et al. 2019, p. 712), and the Energy Regulatory Commission overseeing renewable energy has been criticized for lacking autonomy and independence from political interference.

The ASEAN countries have limited capacity for renewable energy governance. The USD 290 billion of investment required to meet the 23% ASEAN-wide renewable energy target does not include the cost of governance reform. Building institutions and capacity to support renewable energy also requires substantial investment. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) is an important player that can strengthen the capacity of the ASEAN countries. However, the region is one of the least represented in IRENA. In 2020, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand were official members, but they were among the last countries in the world to join. One ASEAN country that has not joined IRENA is Vietnam—and it is actually doing better than the other ASEAN countries in attracting renewable energy investment (Vakulchuk et al. 2020a). This may indicate that membership in IRENA is not decisive. Alternatively, it is also possible that, had it joined IRENA, Vietnam could have attracted even more investment even earlier.

4.3 Renewable energy governance: overcoming institutional carbon lock-in

The ASEAN countries have made progress in setting targets and adopting legislation and policies based on best practices. However, as of 2022, they have not yet built institutions to implement these policies. As shown above, existing government bodies lack the capacity, knowledge, and experience for governing renewable energy.

Are there possible low-hanging measures that could improve renewable energy governance and overcome carbon lock-in? One solution may be to create a resource pool with a high concentration of human capital, knowledge, skills, and regulatory and controlling functions all in one place. This could either be achieved through deep reform of old fossil-fuel ministries or by establishing new ministries for renewable energy. Australia, Egypt, India, and Mauritius may serve as examples: they have prioritized renewables by creating autonomous government bodies that have formed resource pools for renewable energy and have become powerful players over time (Phillips and Newell 2013; Hua et al. 2016; Ministry of Energy and Public Utilities 2020). In 2015, the Mauritius Renewable Energy Agency was established in order to “create an enabling environment for the development of renewable energy” and to better implement regulations and enforce policies (Ministry of Energy and Public Utilities 2020).

Unlike the establishment of a small and marginal renewables department within an oil/gas ministry, setting up a large, autonomous ministry sends a strong, positive signal to investors. Creating a new ministry implies deep institutional and structural changes rather than cosmetic ones. It is also likely to lead to more human and capital resources being channeled to renewable energy governance. Figure 3 presents a list of lessons learned from various countries.

A study of 48 countries shows that names of ministries signal a country’s political attention and prioritization of a particular issue and have an impact on energy policy outputs: a ministry with “energy,” “climate,” and/or “environment” in its name is more likely to promote low-carbon energy sources (Tosun 2018).

Setting up a new renewable energy ministry and assigning real power to it is a pragmatic and symbolic act that can attract investors. In countries that succeeded in attracting investment, this was not a simple act of renaming a government body: it reflected an actual change in the governance system. However, this alone cannot solve all the problems, because countries still need to invest in human capital, provide professionals with new skills, accumulate years of experience in renewable energy implementation through trial and error, and ensure that the right policies are designed and enforced. However, such an institution is important because it can be established relatively quickly, helping to boost investor confidence from the start (Vakulchuk et al. 2017).

Such governance restructuring does not necessarily imply replacing, say, a ministry of oil and gas with a ministry of renewable energy. The case of India shows that unbundling rather than replacing energy governance bodies can prove effective. India’s Ministry of Power, Coal and Non-Conventional Energy Sources was unbundled into three separate ministries in 1992. The Ministry of Non-Conventional Energy Sources was renamed the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy in 2006; since then, it has co-existed with a separate Ministry of Coal and Power and one of Petroleum and Natural Gas. Over time, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy has become an influential player with broad decision-making powers and responsibilities. The Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency also played an important role in streamlining the financing of renewable energy projects and mobilizing private-sector investment (United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance 2007; Phillips and Newell 2013).

Targeted political support and commitment to renewables, including institutional reform, are the main factors behind India’s renewable energy success story. Despite remaining stuck in carbon lock-in (with continuing coal consumption), India has managed to enhance the share of renewables in its energy governance system substantially, becoming a leading global player in attracting investment (see Appendix). This success is being imitated across Asia (Lieven 2019).

Although most ASEAN countries express support for renewable energy, they also strongly support the continued expansion of fossil fuels—coal in particular. The region remains one of the most fossil fuel-intensive in the world. As of 2020, there are two parallel energy trends in the ASEAN member states. First, investment in new coal production and coal-fired power plants is continuing at a rapid pace, often supported by subsidies. The role of coal in the energy mix is set to keep growing: projected demand for coal in 2040 is 400 million metric tons of oil equivalent, twice as much as in 2019 (IEA 2019). Second, the ASEAN countries intend to ramp up renewable energy, not only as an energy source to promote decarbonization but also a potential source of much-needed FDI.

From a climate change perspective, these two trends are contradictory. Some scholars note that major progress on renewables in ASEAN will be possible only if fossil-fuel subsidies are eliminated (Abdullah 2005; Shi 2016; Erdiwansyah et al. 2019; Vakulchuk et al. 2020e). Malaysia is one of the few countries in the region that has removed fossil-fuel subsidies, a policy move deemed important for renewable energy growth (Oh et al. 2018).

Decades of institutional support for fossil fuels have led to the existence of influential fossil-fuel lobbies. Fossil fuel institutions have a long history of institutional resistance to renewable energy development in ASEAN. A case in point is the opposition from Malaysia’s national utility, Tenaga Nasional Berhad, to the implementation of the Small Renewable Energy Power (SREP) Program between 2001 and 2010 (Sovacool and Drupady 2011).

By contrast, the history of renewable energy is rather short, and the industry has received limited or no support from the main government institutions (e.g., ministries of energy) in all the ASEAN countries (see Sect. 4.2). However, the case of India shows that it is possible to move forward with renewable energy without immediately dismantling, or getting into conflict with, older fossil fuel structures.

4.4 Improving the business climate

In addition to designing and adopting sound policies and increasing the share of renewables in the governance system, it is critical to improve the investment climate and communication. Failure to communicate serious moves toward green energy makes investment less attractive: investors, increasingly worried about reputational losses, are prioritizing markets with conditions favorable for decarbonization.

As part of their global decarbonization and climate change strategies, many large international corporations and investors have been withdrawing their capital from countries and projects that rely on fossil fuels. For example, the USD 1 trillion Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund was barred from investing in major coal companies in 2015. By contrast, Siemens’ decision to continue investment in the Adani coal mine in Australia in 2020 resulted in serious reputational damage for the company. Some major ASEAN investors are becoming increasingly aware of such risks. For instance, Singapore’s Temasek, a major fossil fuel investor with a total capital of USD 230 billion, declared its intention to look into renewables and establish a specialized renewables investment unit. Nagi Hamiyeh, head of Temasek International, noted that as renewable energy reached grid parity, “we believe that these [renewables] make much more sense for us to invest in, more than fossil fuels” (The Business Times 2019).

It is increasingly evident that merely copy-pasting policies, even best practices, is not sufficient to attract investment (Seriño 2018). Only a few countries in the world have not set renewable energy targets or adopted legislation on feed-in tariffs or auctions. In 2018, 146 countries set themselves renewable energy targets; 138 established support policies, and 113 passed national renewable energy laws (Crossley 2020). With the transition to renewables already well underway, more comprehensive measures are needed for countries to stand out as especially attractive investment destinations. If they want to be renewable energy investment winners, the ASEAN member states will need to ask themselves: What is our added value in this international context? What can we offer to investors that they cannot find elsewhere?

Awareness-raising and communication through investment climate rankings matter (Jayasuriya 2011; Corcoran and Gillanders 2015; Vakulchuk et al. 2017). Jayasuriya (2011) found a relationship between improvements made by countries, reflected in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index, and higher levels of FDI. However, if the reforms reflected in the ranking score exist only on paper, they are unlikely to attract investors. Improvements in rankings should reflect not only legal changes but also genuine, profound reforms undertaken.

Regarding indices specific to renewable energy and its investment climate attractiveness, Ernst & Young’s RECAI and the World Bank’s RISE Index are the two main indices that inform policymakers and global investors. RECAI ranks 40 countries on the basis of policy enablement, project delivery, energy security, affordability, macroeconomic stability and technology potential (Ernst & Young 2019). In the 2019 update of RECAI, it was noted that as markets move toward grid parity, these indicators become significantly more important for investment decisions than “artificial” motivations such as targets set by governments. Policy implementation and effective governance in the energy sector are also becoming increasingly important in light of the ongoing global energy transition (Gielen et al. 2019; Overland et al. 2019; Aleluia et al. 2022). According to the World Economic Forum (2018):

[T]here is a real risk of underinvestment across almost all energy technologies—and it’s not due to a lack of capital. Markets are awash with capital. Rather it’s policies that need to step up and bridge the gap between finance availability and energy investment needs. Governments have always played an important role in energy investment, but this role has been increasing due to both geography and technology.

The encouraging news for ASEAN is that four of its member states are already included in RECAI and are thus seen as participants in the global race for renewable energy investment. However, they are all located in the lower half of the ranking: Vietnam is ranked 26th, the Philippines 27th, Thailand 35th, and Indonesia 40th.

The World Bank’s RISE Index, which focuses on sustainable energy, not just renewable energy, is broader in geographical scope and indicators. It covers 132 countries and uses 27 indicators, seven of which are devoted specifically to renewable energy (see the seven indicators in Table 3). ASEAN members are mid-level performers in the RISE Index (see Table 5). However, they are not at the bottom either. ASEAN’s best performer, Vietnam, is ranked 35th, while its worst performer, Myanmar, is 111th.

5 Discussion

We have reviewed three areas relevant for ASEAN’s capacity to attract investment in renewable energy: legislation, governance reform and the business climate. Using a traffic-light approach, we summarize the key findings in Table 6, which addresses the research questions of this study: (1) Why, despite the positive rhetoric, has ASEAN largely failed to attract significant investment in renewable energy since the signing of the Paris Agreement? (2) How can renewable energy governance and the business climate be improved?

Although six ASEAN countries have achieved notable success in adopting advanced regulatory and fiscal policies, there has been little progress on reform of the governance system, and the business climate for renewable energy has seen little improvement in most ASEAN member states. Some have managed to develop major renewable energy portfolios (Malaysia, Vietnam), but scant progress has been achieved by Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, and the Philippines.

To reach ASEAN’s target of 23% renewable energy by 2025, USD 290 billion of investment will be needed during the period from 2016 to 2025. Meeting the target will require major reform of the energy governance systems across the ASEAN countries—and overcoming carbon lock-in. Over the period 2006–2018, the volume of investment remained largely unchanged for the entire region, indicating stagnation. Only the year 2018 stands out, when USD 7 billion were invested.

In 2019–2021, the political rhetoric and news on energy developments in Southeast Asia indicated positive attitudes toward renewables across the region. Now the region needs to carry out major reforms to match the rhetoric.

The progress in adopting renewable energy regulations and individual success stories (as in Vietnam) are encouraging for the entire region and an important first step. Malaysia is the world’s third-largest producer of PV cells and modules, yet its domestic solar deployment remains limited. Nearly 100% of the manufactured PV products are exported. Although it succeeded in attracting foreign investors to invest in the production of PV products, Malaysia has failed to provide the conditions to attract investment in the domestic deployment of large-scale solar farms.

6 Conclusions

Based on our analysis, we propose three policy measures to attract more investment in renewable energy in the ASEAN countries. First, the member states could continue to adopt best-practice policies and incentives—and put them into practice. In particular, they need to strengthen their practical experience of managing tenders, feed-in tariffs, and auctions.

Second, each ASEAN country could create a ministry or similarly high-level governing body responsible for renewable energy. This will help build a human and institutional resource pool for renewables and increase the share of renewables in the energy governance system. Such a body could be unbundled from existing energy ministries, to ensure greater autonomy, decision-making power, and expertise, and to obtain better service for investors.

Third, the ASEAN countries need to improve their position in rankings of the renewable energy investment climate. They should actively communicate their reform progress and share success stories with the other ASEAN member states and foreign investors.

References

Abdullah K (2005) Renewable energy conversion and utilization in ASEAN countries. Energy 30:119–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2004.04.027

ACE (2020) ACCEPT-renewable energy & energy efficiency policy database. ASEAN energy database system. ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE), Jakarta

ACE (2022) ASEAN energy outlook forum 2022. https://aseanenergy.org/

Adhikari S, Mithulananthan N, Dutta A, Mathias AJ (2008) Potential of sustainable energy technologies under CDM in Thailand: opportunities and barriers. Renew Energy 33:2122–2133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2007.12.017

Agócs C (1997) Institutionalized resistance to organizational change: Denial, inaction and repression. J Bus Ethics 16:917–931. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017939404578

Ahmad S, Tahar RM (2014) Selection of renewable energy sources for sustainable development of electricity generation system using analytic hierarchy process: a case of Malaysia. Renew Energy 63:458–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2013.10.001

Ahmed T, Mekhilef S, Shah R et al (2017a) ASEAN power grid: a secure transmission infrastructure for clean and sustainable energy for South-East Asia. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 67:1420–1435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.055

Ahmed T, Mekhilef S, Shah R, Mithulananthan N (2017b) Investigation into transmission options for cross-border power trading in ASEAN power grid. Energy Policy 108:91–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.05.020

Aleluia J, Tharakan P, Chikkatur AP et al (2022) Accelerating a clean energy transition in Southeast Asia: role of governments and public policy. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 159:112226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112226

Ali G, Nitivattananon V, Abbas S, Sabir M (2012) Green waste to biogas: renewable energy possibilities for Thailand’s green markets. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 16:5423–5429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.05.021

ASEAN (2020) Agreement on ASEAN Energy Cooperation, of 24 June 1986, Manila.

ASEAN (2021) ASEAN development outlook. ASEAN Secretariat. https://aseanenergy.org/

Bakker K (1999) The politics of hydropower: developing the Mekong. Polit Geogr 18:209–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(98)00085-7

Bekhet HA, Othman NS (2018) The role of renewable energy to validate dynamic interaction between CO2 emissions and GDP toward sustainable development in Malaysia. Energy Econ 72:47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2018.03.028

Boomsma TK, Meade N, Fleten S-E (2012) Renewable energy investments under different support schemes: a real options approach. Eur J Oper Res 220:225–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2012.01.017

Brahim SP (2014) Renewable energy and energy security in the Philippines. Energy Procedia 52:480–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2014.07.101

Business Times (2019) Temasek ramps up push into renewables, 18 October.

Chaiyapa W, Esteban M, Kameyama Y (2018) Why go green? Discourse analysis of motivations for Thailand’s oil and gas companies to invest in renewable energy. Energy Policy 120:448–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.05.064

Chang Y, Li Y (2013) Power generation and cross-border grid planning for the integrated ASEAN electricity market: a dynamic linear programming model. Energy Strategy Rev 2:153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2012.12.004

Chang Y, Li Y (2015) Renewable energy and policy options in an integrated ASEAN electricity market: quantitative assessments and policy implications. Energy Policy 85:39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.05.011

Chen W, Fan J, Du H, Zhong P (2022) Investment strategy for renewable energy and electricity service quality under different power structures. JIMO. https://doi.org/10.3934/jimo.2022006

Chua SC, Oh TH (2012) Solar energy outlook in Malaysia. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 16:564–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2011.08.022

Chua SC, Oh TH, Goh WW (2011) Feed-in tariff outlook in Malaysia. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 15:705–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2010.09.009

Chunark P, Limmeechokchai B, Fujimori S, Masui T (2017) Renewable energy achievements in CO2 mitigation in Thailand’s NDCs. Renew Energy 114:1294–1305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2017.08.017

Cicea C, Marinescu C, Popa I, Dobrin C (2014) Environmental efficiency of investments in renewable energy: comparative analysis at macroeconomic level. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 30:555–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.10.034

Corcoran A, Gillanders R (2015) Foreign direct investment and the ease of doing business. Rev World Econ 151:103–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-014-0194-5

Crossley P (2020) Lessons from renewable energy laws: how do countries legislate to support renewables to meet the needs of domestic consumers and renewable producers? University of Sydney

Daubach, Tim (2019) Power play—who’s winning Southeast Asia’s renewables race? Eco-Business. Special Report

Djellouli N, Abdelli L, Elheddad M et al (2022) The effects of non-renewable energy, renewable energy, economic growth, and foreign direct investment on the sustainability of African countries. Renew Energy 183:676–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.10.066

Do TN, Burke PJ, Nguyen HN et al (2021) Vietnam’s solar and wind power success: policy implications for the other ASEAN countries. Energy Sustain Dev 65:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2021.09.002

Dvořák P, Martinát S, der Horst DV et al (2017) Renewable energy investment and job creation; a cross-sectoral assessment for the Czech Republic with reference to EU benchmarks. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 69:360–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.158

Energy Market Authority (2018) Renewable energy developments in ASEAN. Abu Dhabi

Erdiwansyah MR, Sani MSM, Sudhakar K (2019) Renewable energy in Southeast Asia: policies and recommendations. Sci Total Environ 670:1095–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.273

Ernst & Young (2019) RECAI Methodology. Renewable energy country attractiveness index. Ernst & Young Global Limited.

Forsyth T (1999) International investment and climate change: energy technologies for developing countries. Routledge, London

Frankfurt School-UNEP Centre/BNEF (2011) Global trends in renewable energy investment 2011–2019. United Nations Environment Programme and Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt School-UNEP Centre/BNEF (2014) Global trends in renewable energy investment 2014. Frankfurt School of Finance & Management, Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt School-UNEP Centre/BNEF (2019) Global trends in renewable energy investment 2019. Frankfurt School of Finance & Management, Frankfurt am Main

Gan PY, Li Z (2008) An econometric study on long-term energy outlook and the implications of renewable energy utilization in Malaysia. Energy Policy 36:890–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2007.11.003

Gielen D, Boshell F, Saygin D et al (2019) The role of renewable energy in the global energy transformation. Energy Strategy Rev 24:38–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2019.01.006

GreenTech Malaysia (2019) RE goals to attract RM33b in private investments. 11 October

Hasan MH, Mahlia TMI, Nur H (2012) A review on energy scenario and sustainable energy in Indonesia. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 16:2316–2328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2011.12.007

Hasudungan HWV, Sabaruddin SS (2018) Financing renewable energy in Indonesia: a CGE analysis of feed-in tariff schemes. Bull Indones Econ Stud 54:233–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2018.1450961

Hua Y, Oliphant M, Hu EJ (2016) Development of renewable energy in Australia and China: a comparison of policies and status. Renew Energy 85:1044–1051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2015.07.060

Huang YW, Kittner N, Kammen DM (2019) ASEAN grid flexibility: Preparedness for grid integration of renewable energy. Energy Policy 128:711–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.01.025

Huber M, Roger A, Hamacher T (2015) Optimizing long-term investments for a sustainable development of the ASEAN power system. Energy 88:180–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2015.04.065

IEA (2019) Southeast Asia energy outlook 2019. International Energy Agency, Pari.

IRENA (2017) Renewable energy market analysis, Southeast Asia. International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Abu Dhabi

IRENA (2018) Renewable energy market analysis, Southeast Asia. International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Abu Dhabi

IRENA & ACE (2016) Renewable energy outlook for ASEAN: a REmap analysis. International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE), Jakarta

Islam MT, Huda N, Saidur R (2019) Current energy mix and techno-economic analysis of concentrating solar power (CSP) technologies in Malaysia. Renew Energy 140:789–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.03.107

Jayasuriya D (2011) Improvements in the World Bank’s ease of doing business rankings: do they translate into greater foreign direct investment inflows? World Bank.

Karki SK, Mann MD, Salehfar H (2005) Energy and environment in the ASEAN: challenges and opportunities. Energy Policy 33:499–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2003.08.014

Keyuraphan S, Thanarak P, Ketjoy N, Rakwichian W (2012) Subsidy schemes of renewable energy policy for electricity generation in Thailand. Procedia Eng 32:440–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.01.1291

Khuong PM, McKenna R, Fichtner W (2019) Analyzing drivers of renewable energy development in Southeast Asia countries with correlation and decomposition methods. J Clean Prod 213:710–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.192

Kim K, Park H, Kim H (2017) Real options analysis for renewable energy investment decisions in developing countries. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 75:918–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.073

Kumar S (2016) Assessment of renewables for energy security and carbon mitigation in Southeast Asia: the case of Indonesia and Thailand. Appl Energy 163:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.11.019

Lee J-O, Adam S (2022) ASEAN is poised for post-pandemic inclusive growth and prosperity—here’s why. World Economic Forum

Li Y, Chang Y (2019) Road transport electrification and energy security in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations: quantitative analysis and policy implications. Energy Policy 129:805–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.02.048

Lieven A (2019) How climate change will transform the global balance of power. Financial Times, 5 November

Liu X, Zhang S, Bae J (2017) The impact of renewable energy and agriculture on carbon dioxide emissions: investigating the environmental Kuznets curve in four selected ASEAN countries. J Clean Prod 164:1239–1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.086

Liu Y, Noor R (2020) Energy efficiency in ASEAN: trends and financing schemes. Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) Working Paper, No. 1196

Mahesh A, Shoba Jasmin KS (2013) Role of renewable energy investment in India: an alternative to CO2 mitigation. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 26:414–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.05.069

Malik AQ (2011) Assessment of the potential of renewables for Brunei Darussalam. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 15:427–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2010.08.014

Marquardt J (2014) A struggle of multi-level governance: promoting renewable energy in Indonesia. Energy Procedia 58:87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2014.10.413

Marquardt J (2017) How power affects policy implementation: Lessons from the Philippines. J Curr Southeast Asian Aff 36:3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341703600101

Ministry of Energy and Public Utilities (2020) Energy sector. Mauritius Ministry of Energy and Public Utilities

Nepal R, Phoumin H, Khatri A (2021) Green technology development and deployment in the ASEAN: lessons learned and ways forward. In: Phoumin H, Taghizadeh-Hesary F, Kimura F, Arima J (eds) Energy sustainability and climate change in ASEAN. Springer Singapore, Singapore, pp 217–238

Nguyen KQ (2007a) Alternatives to grid extension for rural electrification: decentralized renewable energy technologies in Vietnam. Energy Policy 35:2579–2589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2006.10.004

Nguyen KQ (2007b) Wind energy in Vietnam: resource assessment, development status and future implications. Energy Policy 35:1405–1413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2006.04.011

Nguyen NT, Ha-Duong M (2009) Economic potential of renewable energy in Vietnam’s power sector. Energy Policy 37:1601–1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.12.026

Nguyen PA, Abbott M, Nguyen TLT (2019) The development and cost of renewable energy resources in Vietnam. Utilities Policy 57:59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2019.01.009

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

NREL (2019) Exploring renewable energy opportunities in select Southeast Asian countries. A geospatial analysis of the levelized cost of energy of utility-scale wind and solar photovoltaics. National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Washington, DC

Oh TH, Hasanuzzaman M, Selvaraj J et al (2018) Energy policy and alternative energy in Malaysia: issues and challenges for sustainable growth: an update. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 81:3021–3031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.06.112

Ong HC, Mahlia TMI, Masjuki HH (2011) A review on energy scenario and sustainable energy in Malaysia. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 15:639–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2010.09.043

Overland I, Bazilian M, Ilimbek Uulu T et al (2019) The GeGaLo Index: geopolitical gains and losses after energy transition. Energy Strategy Rev 26:100406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2019.100406

Overland I, Sagbakken HF, Chan H-Y et al (2021) The ASEAN climate and energy paradox. Energy Clim Chang 2:100019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egycc.2020.100019

Pacudan R (2014) Electricity price impacts of feed-in tariff policies: the cases of Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. In: Energy market integration in East Asia: energy trade, cross border electricity, and price mechanism. ERIA, Jakarta, pp 283–319

Pacudan R (2016) Implications of applying solar industry best practice resource estimation on project financing. Energy Policy 95:489–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.02.021

Pacudan R (2018) Feed-in tariff vs incentivized self-consumption: options for residential solar PV policy in Brunei Darussalam. Renew Energy 122:362–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.01.102

Phillips J, Newell P (2013) The governance of clean energy in India: the clean development mechanism (CDM) and domestic energy politics. Energy Policy 59:654–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.04.019

Phoumin H, Kimura F, Arima J (2021) ASEAN energy landscape and emissions: the modelling scenarios and policy implications. In: Phoumin H, Taghizadeh-Hesary F, Kimura F, Arima J (eds) Energy sustainability and climate change in ASEAN. Springer Singapore, Singapore, pp 111–146

Polzin F, Migendt M, Täube FA, von Flotow P (2015) Public policy influence on renewable energy investments: a panel data study across OECD countries. Energy Policy 80:98–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.01.026

Pratiwi S, Juerges N (2020) Review of the impact of renewable energy development on the environment and nature conservation in Southeast Asia. Energy Ecol Environ 5:221–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-020-00166-2

Ralph N, Hancock L (2019) Energy security, transnational politics, and renewable electricity exports in Australia and Southeast Asia. Energy Res Soc Sci 49:233–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.10.023

Razzouk A (2018) Southeast Asia is the global laggard in renewables, but for how much longer? Eco-Business. Opinion. 6 July

REN21 (2019) Renewables 2019 global status report. Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (REN21), Paris

REN21 (2022) Renewables 2022 global status report. Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (REN21), Paris

Rentier G, Lelieveldt H, Kramer GJ (2019) Varieties of coal-fired power phase-out across Europe. Energy Policy 132:620–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.05.042

Reusswig F, Komendantova N, Battaglini A (2018) New governance challenges and conflicts of the energy transition: Renewable electricity generation and transmission as contested socio-technical options. In: Scholten D (ed) The geopolitics of renewables. Springer, Cham, pp 231–256

Roxas F, Santiago A (2016) Alternative framework for renewable energy planning in the Philippines. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 59:1396–1404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.01.084

Sadettanh K (2004) Renewable energy resources potential in Lao PDR. Energy Sources 26:9–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00908310490266994

Salam MA, Yazdani MG, Rahman QM et al (2019) Investigation of wind energy potentials in Brunei Darussalam. Front Energy 13:731–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11708-018-0528-4

Seriño MNV (2018) Diversification of nonhydro renewable energy sources in developing countries. Energy Ecol Environ 3:317–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-018-0106-y

Shamsuddin AH (2012) Development of renewable energy in Malaysia: strategic initiatives for carbon reduction in the power generation sector. Procedia Eng 49:384–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.10.150

Sharpe SA, Martinez-Fernandez CM (2021) The implications of green employment: making a just transition in ASEAN. Sustainability 13:7389. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137389

Shi X (2016) The future of ASEAN energy mix: a SWOT analysis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 53:672–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.09.010

Siala K, Stich J (2016) Estimation of the PV potential in ASEAN with a high spatial and temporal resolution. Renew Energy 88:445–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2015.11.061

Sovacool BK (2010) A comparative analysis of renewable electricity support mechanisms for Southeast Asia. Energy 35:1779–1793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2009.12.030

Sovacool BK, Bulan LC (2011) Meeting targets, missing people: The energy security implications of the Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy (SCORE). Contemp Southeast Asia 33:56–82

Sovacool BK, Bulan LC (2012) Energy security and hydropower development in Malaysia: the drivers and challenges facing the Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy (SCORE). Renew Energy 40:113–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2011.09.032

Sovacool BK, Drupady IM (2011) Examining the small renewable energy power (SREP) program in Malaysia. Energy Policy 39:7244–7256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.08.045

Tongsopit S, Greacen C (2013) An assessment of Thailand’s feed-in tariff program. Renew Energy 60:439–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2013.05.036

Tongsopit S, Moungchareon S, Aksornkij A, Potisat T (2016) Business models and financing options for a rapid scale-up of rooftop solar power systems in Thailand. Energy Policy 95:447–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.01.023

Tosun J (2018) Investigating ministry names for comparative policy analysis: lessons from energy governance. J Comp Policy Anal Res Pract 20:324–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2018.1467430

Tun MM (2019) An overview of renewable energy sources and their energy potential for sustainable development in Myanmar. Eur J Sustain Dev Res. https://doi.org/10.20897/ejosdr/3951

Tuna G, Tuna VE (2019) The asymmetric causal relationship between renewable and NON-RENEWABLE energy consumption and economic growth in the ASEAN-5 countries. Resour Policy 62:114–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.03.010

United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance (2007) Global trends in sustainable energy investment 2007. Analysis of trends and issues in the financing of renewable energy and energy efficiency in OECD and developing countries. United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance Ltd

United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance (2008) Global trends in sustainable energy investment 2008. Analysis of trends and issues in the financing of renewable energy and energy efficiency. United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance Ltd

United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance (2009) Global trends in sustainable energy investment 2009. Analysis of trends and issues in the financing of renewable energy and energy efficiency. United Nations Environment Programme

United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance (2010) Global trends in sustainable energy investment 2010. Analysis of trends and issues in the financing of renewable energy and energy efficiency. United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance

Unruh GC (2000) Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 28:817–830. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(00)00070-7

Unruh GC (2002) Escaping carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 30:317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(01)00098-2

Vakulchuk R, Hlaing KK, Naing EZ et al (2017) Myanmar’s attractiveness for investment in the energy sector: a comparative international perspective. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3023133

Vakulchuk R, Chan H-Y, Kresnawan MR et al (2020a) Vietnam: six ways to keep up the renewable energy investment success. ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341794415

Vakulchuk R, Hoy-Yen Chan, Kresnawan MR et al (2020b) Thailand: improving the business climate for renewable energy investment. ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.16512.66568

Vakulchuk R, Hoy-Yen Chan, Kresnawan MR et al (2020c) Singapore: how to attract more investment in renewable energy? ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12318.36165

Vakulchuk R, Hoy-Yen Chan, Kresnawan MR et al (2020d) Lao PDR: How to attract more investment in small-scale renewable energy? ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31192.72966

Vakulchuk R, Hoy-Yen Chan, Kresnawan MR et al (2020e) Indonesia: how to boost investment in renewable energy. ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.11060.07047

VOA (2018) Indonesia struggles to meet renewable energy target. Voice of America (VOA). East Asia Pacific

Wiseman HJ (2011) Expanding regional renewable governance. Harv Environ Law Rev 35:477–540

World Bank (2018) Regulatory indicators for sustainable energy. World Bank Group

World Economic Forum (2018) We’re getting closer to completing the energy transition. World Economic Forum (WEF)

Yatim P, Mamat M-N, Mohamad-Zailani SH, Ramlee S (2016) Energy policy shifts towards sustainable energy future for Malaysia. Clean Technol Environ Policy 18:1685–1695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-016-1151-x

Zimmer A, Jakob M, Steckel JC (2015) What motivates Vietnam to strive for a low-carbon economy? On the drivers of climate policy in a developing country. Energy Sustain Dev 24:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2014.10.003

Acknowledgements

This article is a product of the ASEAN Climate Change and Energy Project (ACCEPT 2), which is funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway and implemented by the ASEAN Centre for Energy in cooperation with the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. The views expressed here are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of any of these institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vakulchuk, R., Overland, I. & Suryadi, B. ASEAN’s energy transition: how to attract more investment in renewable energy. Energ. Ecol. Environ. 8, 1–16 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-022-00261-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-022-00261-6