Abstract

Introduction:

This case report aimed to report the effectiveness of creative occupations on a child with anxiety problems in a mental health center in Iran.Case Presentation:

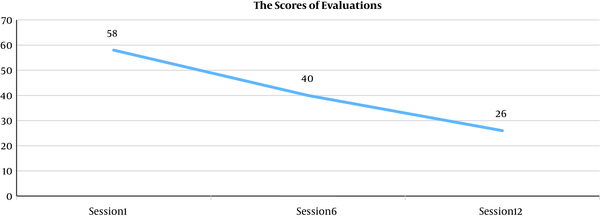

This case report has been performed in 12 sessions with a three-month follow-up. The Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS) and a structured clinical interview were used to collect information. The child's score on SCAS was 66 at the first session, which was then reduced to 41 at the sixth session, and 27 at the twelfth session. The child's father also confirmed the positive effects of the intervention on the child's behavior.Conclusions:

Creative occupations showed a positive effect on reducing the severity of anxiety symptoms. These effects remained to a large extent during the intervention.Keywords

1. Introduction

According to recent epidemiologic studies, about 12% of elementary-school-age children face at least one of the anxiety disorder criteria (1), which are major contributors to disrupting children's functions such as class activities, social participation, and interaction with family members (2).

In addition to pharmaceutical treatments, non-medical approaches are widely using to reduce children's anxiety (3). In this regard, occupational therapists (OTs) use "occupations" (daily life activities) as a therapeutic tool to enable or enhancing children's participation in settings such as school, home, or community. They also use craft and manual activities, along with their specialized knowledge. So, it can be argued that art and craft are the main tools in OT practice (4).

However, the use of art in occupational therapy is rather limited, and less than 5% of OTs are interested in the application of creative arts in their interventions. In fact, art and creativity in OT settings have been declined many times (3). Unfortunately, OTs mostly do not pay enough attention to art and play as a basic intervention to treat children with anxiety problems. Most of the studies on the effectiveness of artistic and creative occupations are from western countries. In this regard, Reynolds performed a study on the application of art in children during the 2000s. This study intended to examine personal meanings of engagement in self-chosen needlecraft activities and also its role in self-management of depression. They reported that planning for the artwork also helped to draw the participants' attention away from negative thoughts about illness (5).

In other contexts with low and average income, only four studies related to mental health interventions have been carried out (6). Moreover, between 2000 and 2014, three studies have evaluated the effectiveness of creative art therapy on anxiety disorder in children. However, particularly regarding panic disorder, all of these studies were carried out in groups and education systems (7). These issues may challenge OTs in different cultural contexts when designing therapeutic plans in the form of creative activities in children's rehabilitation. This is more critical when realizing that there is no single definition for creativity (5), as there is no unique definition for creativity in different contexts. However, in occupational therapy, creative activities are defined as a means to adjust and endure unsuitable conditions (5). Therefore, because of the aforementioned gaps in this age group and context as well as differences between individual and group therapies, developing an intervention to resolve the related issues would be valuable.

2. Case Presentation

The referred, D, was an 8-year-old girl in the second grade of elementary school. After school, she could not spend any time with her parents because were busy at work. She was referred to an OT by a child psychiatrist due to her extraordinary anxiety and shyness, which was reported by her teacher based on her learning disorders and extreme shyness. After receiving consent from parents, her father was interviewed in the assessment session. It was shown that D had different problems in different cases during her school time. Academic failure, lack of concentration and attention, lack of participation in classroom activities, and lack of communication with classmates, along with anxiety symptoms such as restlessness, fatigue, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbances, had worried her parents. In addition, according to her father's sayings, her self-confidence decreased significantly, so that she was avoiding most activities that she was able to do skillfully. For example, despite repeated practice at home and mastery of the subject, she had many problems in orally reporting stories in the classroom.

She couldn't defend herself and expressing her wishes and ideas. In addition, she was unable to express her emotions and opposition, and subsequently, would express little desire to participate in group games. Besides, D was afraid of staying at home alone, and thus the parents had to rearrange their schedules so as not to leave her alone at home. Currently, D uses Biperiden medication under the supervision of a psychiatrist. The father also noted that she had a mild form of anxiety and shyness. More investigation on the family circumstances suggested that the family expected D's continuous success, which led to the formation of a perfectionist personality in the child in a way that each activity must be performed successfully until the end; otherwise, the child would show no tendency for other activities.

The child was evaluated based on Rounet's approach with children. In Rounet's interview pattern, paintings and pictures are used to achieve the child`s point of view toward the environment and themselves. By using this method, in addition to obtaining facts and data about the child, the child is committed to searching for responses resulting from experimental events and taking place at a lower level of consciousness. The power of inquiry enlightens the hidden aspects of reality (8).

The fear of being away from the parents was revealed during the interview; accordingly, the child insisted on her father's presence in the treatment room. The low voice, poor eye contact, anxiety, impulsive movements of the hands and feet, blushing face, and passivity of D, along with her extreme obedience from the therapist, were obvious during the interview.

The Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS) (Spence, 1998) was used to evaluate the case. It comprises 45 items, of which 38 are graded, and six positive items are not calculated. The highest score is 114; the higher the score, the more severe the anxiety of the child. The questionnaire includes six areas of agoraphobia, separation anxiety, fear of physical harm, social phobia, intellectual-practical obsession, and public anxiety. It has high convergence validity with other children's anxiety questionnaires and also has high reliability (9). However, it is not reliable and valid in the Persian version. In the initial SCAS analysis, the score of D was 66, meaning abnormal anxiety about her position and age. The results of the test in sessions 6 and 12 showed the effectiveness of the intervention.

2.1. Intervention Process

The child's occupations (including social participation, education, and leisure, and in some cases, the activity of daily living) were limited. In the process of the study, we used the free painting therapy method consisting of 12 sessions (once per week), with each session lasting 45-60 minutes (10).

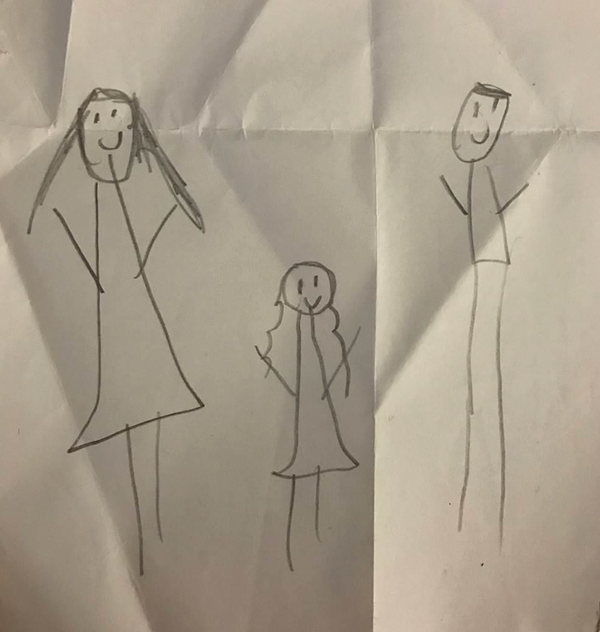

For having a therapeutic relationship with the child, in the first session, the therapist asked her to paint anything she liked about her wishes (Figure 1). Then, the therapist requested her to express everything about her painting. During this session, the therapist also asked D to have comments about her painting to find out about her values and also her behavioral strengths and weaknesses. The pattern of the child's feelings and emotions was identified during the session (Figure 1).

The first session. Purpose: Communication with the child

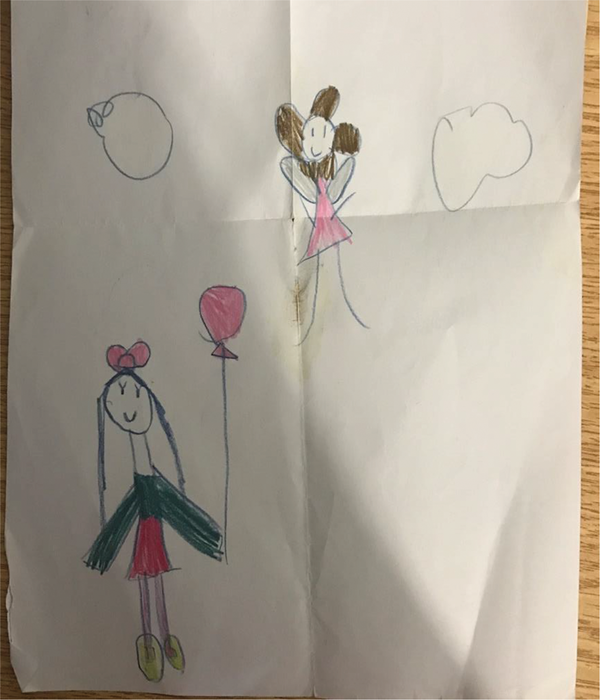

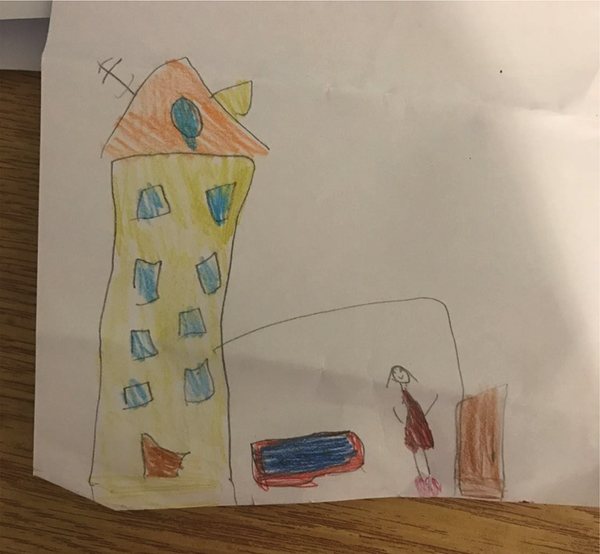

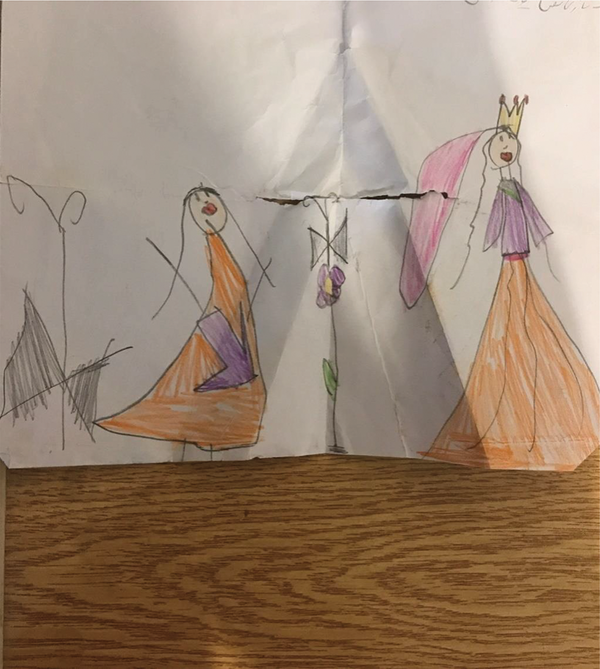

Painting was continued for 5 sessions until the child could do it in a better manner and expressed all her thoughts about her paintings (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Afterward, other favorite activities of the child, such as storytelling, poetry, and play activities, were performed despite her poor eye contact and low voice level. For example, she participated in some plays that needed eye contact. Her voice was recorded during the performance and was presented to her as feedback with clarifications from the therapist. In this way, she understood how to use her moderate voice tone while communicating. As another example, the therapist told D a story while she was listening carefully. Then, she recited the story to the therapist and received the necessary feedback from the therapist. In another play, she named subjects in her mind and then asked the therapist to guess them. Subsequently, she stated whether the therapist guessed correctly. Positive feedbacks were given to the subject after each activity to increase her confidence and encourage her to communicate more effectively. The child's communication and partnership skills improved during the sessions, and she described her mental challenges and stresses to the therapist. This was effective in enhancing therapy goals rapidly. In the sixth session, the child presented her comments about games she liked. This was the sign of appropriate communication between the child and the therapist, and also the sign of the child's preparedness to accept new treatments for her mental challenges.

The second session

The third session

The fourth session (one painting is not presented)

Some consultation was provided to her father at the end of each session to train him on how to communicate with the child, how to increase her self-confidence for self-expression, how to speak according to her age, and how to balance her feelings and emotions. For enhancing her social communication skills, the intervention took placed out of the clinic, with her playing the role of a buyer who ordered an ice cream and asked about its cost for paying.

2.2. Results

Similar to the father's report on her child's improvement, repeating the test in sessions 6th and 12th indicated the ideal therapy process and decreased worrying behaviors. Moreover, anxiety symptoms decreased significantly. Accordingly, the child's test score decreased to 40 (reduction equal to 18 scores) in the sixth session and 26 (reduction equal to 14 scores) in the twelfth session (Figure 5). Similarly, panic, agoraphobia, separation anxiety, and social phobia significantly decreased, as also confirmed by her family. The reduction of effectiveness telling test areas of D's treatment enabled her to have an ordinary life. She had changes in her communicative and behavioral functions during different sessions. Firstly, she revealed some negative behavior patterns, but after some sessions, she confirmed her improved behavior and communication skills with peers. She participated in group games satisfactorily and protected her rights against her playmates. Further, according to her father's report and the SCAS scale results, her confidence level increased.

The maximum and minimum scores

3. Discussion

When children encounter a problem, likely they do not talk about it directly; however, they can express their emotions by playing, paintings, or telling a story (11). Creative activities like storytelling or imaginative plays are vital for problem-solving, adaptive skills, and social participation, as these activities bridge between children's inner world and their emotional needs (12). According to this, we attempted to use painting and storytelling activities to find out about issues that cause anxiety for D.

We also used creative occupations as a tool for social skill demands (like eye contact or speech tone). We observed progress in D's engagement skills during the intervention session. Byrne et al. (2010) believe that art is the only occupation that engages five basic performance skills simultaneously: motor, sensory, emotional, cognitive, and social skills.

The point is that the skills used in art production can be expanded to everyday life challenges (13). Moreover, we attempted to use the presence of the father at home to help manage the child's behavior. Occupational therapists call this co-occupation that encompasses an integrated perspective of clients' engagement in the context and relationship to caregivers (4). Moreover, the therapist realized that the child expanded her skills as needed for her everyday life.

In general, art and craft activities were first used for traditional occupational therapy (14). Decisions of OTs to use creative activities as a therapeutic measure depend on their knowledge of what activity is appropriate for children to achieve goals (3). Selecting the best convenient, creative activity by OTs makes children feel self-efficacious, as they see their ability while involving in such activities and seeing products of their activities (15).

It is recommended to pay attention to creative occupations while dealing with behavioral problems such as anxiety and shyness. The number of instruments used in the study was limited for evaluation of the problem, and thus, the study could not well show the effect of the intervention. Moreover, there was no cooperation in the study with other members of the rehabilitation team for a consultation about intervention plans. Thus, more studies with more instruments and also with other members of the rehabilitation team are required to better evaluate the outcomes of these interventions.

Acknowledgements

References

-

1.

Costello E, Egger HL, Copeland W, Erkanli A, Angold A, Silverman WK, et al. The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am J. 2011;2:56-75. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511994920.004.

-

2.

Ginsburg GS, Becker KD, Drazdowski TK, Tein JY. Treating anxiety disorders in inner city schools: Results from a pilot randomized controlled trial comparing CBT and usual care. Child Youth Care Forum. 2012;41(1):1-19. [PubMed ID: 22701295]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC3373959]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-011-9156-4.

-

3.

Harris E. The meanings of craft to an occupational therapist. Aust Occup Ther J. 2007;54(2):165-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2006.00626.x.

-

4.

American Journal of Occupational Therapy. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process 3nd edition. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;74:1-48. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001.

-

5.

Perruzza N, Kinsella EA. Creative arts occupations in therapeutic practice: A review of the literature. Br J Occup Ther. 2010;73(6):261-8. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210x12759925468943.

-

6.

Jordans MJ, Komproe IH, Tol WA, Kohrt BA, Luitel NP, Macy RD, et al. Evaluation of a classroom-based psychosocial intervention in conflict-affected Nepal: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(7):818-26. [PubMed ID: 20102428]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02209.x.

-

7.

Beauregard C. Effects of classroom-based creative expression programmes on children's well-being. Arts Psychother. 2014;41(3):269-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.04.003.

-

8.

Fransella F. The essential practitioner's handbook of personal construct psychology. John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

-

9.

Spence SH, Barrett PM, Turner CM. Psychometric properties of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale with young adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17(6):605-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00236-0.

-

10.

Amini M, Pashmdarfard M. Effect of painting therapy on reducing the aggression of a child with myelomeningocele: A case study (case report). J Rehabil Med. 2018;7(1).

-

11.

Butler RJ, Green DR. The child within: Taking the young person's perspective by applying personal construct psychology. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2007.

-

12.

Unnsteinsdóttir K. The influence of sandplay and imaginative storytelling on children's learning and emotional-behavioral development in an Icelandic primary school. Arts Psychother. 2012;39(4):328-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.05.004.

-

13.

Byrne P, Raphael EI, Coleman-Wilson A. Art as a transformative occupation. OT Practice. 2010;15:13-7.

-

14.

Horghagen S, Josephsson S, Alsaker S. The use of craft activities as an occupational therapy treatment modality in Norway during 1952-1960. Occup Ther Int. 2007;14(1):42-56. [PubMed ID: 17623378]. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.222.

-

15.

Griffiths S, Corr S. The use of creative activities with people with mental health problems: A survey of occupational therapists. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;70(3):107-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260707000303.