Abstract

In order to estimate the hazard to technological systems due to geomagnetically induced currents (GIC), it is crucial to understand the response of the geoelectric field to a geomagnetic disturbance and to provide quantitative estimates of this field. Most previous studies on GIC and the geoelectric field generated during a geomagnetic storm assume a 1-D conductivity structure of Earth. This assumption however is invalid in coastal regions, where the lateral conductivity contrast is large. In this paper, we investigate the global spatio-temporal pattern of the surface geoelectric field induced by a typical major geomagnetic storm in a conductivity model of Earth with realistic laterally-heterogeneous oceans and continents. Exploiting this model makes the problem fully 3-D. Data from worldwide distributed magnetic observatories are used to construct a realistic model of the magnetospheric source. The results of our numerical studies show large amplification of the geoelectric field in many coastal regions. Peak amplitudes obtained with 3-D modelling exceed the amplitudes obtained in a 1-D model by at least a factor 2, even if the latter makes use of the local vertical conductivity structure. Lithosphere resistivity is a critical parameter, which governs both amplitude and penetration width of the anomalous electric field inland.

Similar content being viewed by others

1. Introduction

Eruptions at Sun’s surface (coronal mass ejections) blow large quantities of charged particles into space. The particle streams interact with Earth’s magnetic field, intensifying the westward directed magnetospheric ring current (Love, 2008). This phenomenon, leading to substantial temporal variations of the geomagnetic field, is known as geomagnetic storm. According to Faraday’s law of induction, the fluctuating geomagnetic field in turn generates an electric field and induces currents in Earth and grounded conducting networks, such as power grids and pipelines (Pirjola, 2000). These geomagnetically induced currents (GIC) can lead to severe damages of the power network, as happened, for example, 1989 in Quebec (Kappenman et al., 1997). Understanding the properties of the geoelectric field is a key consideration in estimating the hazard to technological systems from space weather (Pulkkinen et al., 2007).

So far, most studies of the geoelectric field in connection with GIC were performed on a regional or local scale, considering rather simplified models of the inducing geomagnetic source (see review paper of Thomson et al. (2009) for more details). In addition, most of the studies (except for the works by Beamish et al., 2002; Thomson et al., 2005 and Gilbert, 2005) employed the assumption of a one-dimensional (1-D) conductivity structure of Earth. But it is well-known that the lateral conductivity contrast is large at ocean-land interfaces, making the 1-D assumption invalid in many coastal areas. The literature contains many publications (Parkinson and Jones, 1979; Cox, 1980; Fainberg, 1980; Rikitake and Honkura, 1985; Kuvshinov, 2008; among others) dealing with the study of the coastal (ocean) effect. However, these studies mainly concentrate on either the investigation of Earth’s mantle structure in the presence of oceans or the influence of the ocean effect on the geomagnetic field.

In this paper, we discuss a rigorous numerical scheme that aims to model on a global scale the geoelectric field induced by a geomagnetic storm as close to reality as possible. Based on this scheme, we investigate the global pattern of the geoelectric field during the main phase of the storm (when the largest amplitudes are expected), using a conductivity model of Earth with realistic laterally-heterogeneous oceans and continents, and exploiting a realistic model of the magnetospheric source. Note that estimating the geoelectric field during geomagnetic substorms (i.e. when the auroral currents are intensified, but not necessarily the ring current) is out of scope of this study. In Section 4.3 of this paper, we discuss how our approach could be modified in order to estimate the electric field induced by geomagnetic substorms.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the conductivity model and explains the approach to construct the spatio-temporal model of the magnetospheric source and to calculate the geoelectric field. Section 3 presents the results of our numerical studies, both in terms of modelled time series at specific locations and of modelled snapshots of the global pattern. Discussion and conclusions are presented in Section 4.

2. Methods

For a given impressed source, jext, and a given 3-D conductivity model of Earth, σ(r, ϑ, φ), where r, ϑ and φ are distance from Earth’s centre, colatitude and longitude, respectively, it is possible to calculate the time series of the electric field E (and the magnetic field B) by solving numerically Maxwell’s equations

where μ0 is the magnetic permeability of free space. In the following, we describe the conductivity model (Section 2.1), explain the construction of the source model (Section 2.2), and outline the scheme to estimate the geoelectric field (Section 2.3).

2.1 Conductivity model

Our model consists of a thin spherical layer of laterally variable conductance S(ϑ, φ) at Earth’s surface and a radially symmetric (1-D) conductivity structure underneath. The shell conductance S (Fig. 1(a)) is obtained by considering contributions both from seawater and sediments. The conductance of seawater has been taken from Manoj et al. (2006) and accounts for ocean bathymetry, ocean salinity, temperature and pressure. Conductance of the sediments (in continental as well as oceanic regions) is based on the global sediment thicknesses given by Laske and Masters (1997) and calculated by a heuristic procedure similar to that described in Everett et al. (2003). The resolution of the model is chosen to be 1° × 1°. Note that calculations on a denser mesh with a resolution of 0.3° × 0.3° revealed only negligible differences in the final results.

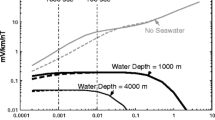

Conductivity model. a) Surface conductance map (in S) with a resolution of 1° × 1°, for calculations scaled to a thickness of 1 km. The white dots indicate the locations of the magnetic observatories of which data have been used for the analysis. b) Different 1-D conductivity sections (in S/m) tested in this study.

The importance of the underlying conductivity structure was tested by simulating induction in models with different 1-D sections. Our basic 1-D profile consists of a resistive lithosphere with a thickness of 100 km and a layered model underneath, derived from 5 years of CHAMP, Ørsted and SAC-C magnetic data by Kuvshinov and Olsen (2006). Previous model studies that aimed to investigate the ocean effect in Sq and Dst geomagnetic variations (Kuvshinov et al., 1999) demonstrated that the resistivity of the lithosphere is a key parameter, which governs the behaviour of the magnetic field at ocean-land contacts. In order to investigate the effect of this parameter, lithosphere resistivities of 300 Ωm and 3000 Ωm were tested. Note that we do not account for lateral variations in the thickness and resistivity of the lithosphere; the reasoning for this is discussed in Section 4.2.

Alternative 1-D sections are based on the study by Baba et al. (2010). The authors derived models of the 1-D conductivity structure beneath the Philippine Sea and the North Pacific using sea floor magnetotelluric data, which are more sensitive to structures in the upper mantle than satellite data. Additional computations were performed with 1-D sections based on the results by Baba et al. (2010), but using a uniform resistivity for the lithosphere (constituting the upper 100 km). These additional models allow to investigate the importance of the shallow 1-D structure by comparison with the results obtained in the original structures derived by Baba et al. (2010) and the importance of the deep 1-D structure by comparison with the results obtained in the basic model. This yields the following six 1-D sections under consideration:

-

(a)

Model derived by Kuvshinov and Olsen (2006) from satellite data with lithosphere of 300 Ωm (R = 3 · 107 Ωm2)

-

(b)

Model derived by Kuvshinov and Olsen (2006) from satellite data with lithosphere of 3000 Ωm (R = 3 · 108 Ωm2)

-

(c)

Model derived by Baba et al. (2010) for the Philippine Sea with lithosphere of 300 Ωm (R = 3 · 107 Ωm2)

-

(d)

Model derived by Baba et al. (2010) for the North Pacific with lithosphere of 3000 Ωm (R = 3 · 108 Ωm2)

-

(e)

Model derived by Baba et al. (2010) for the Philippine Sea (R = 5 · 107 Ωm2)

-

(f)

Model derived by Baba et al. (2010) for the North Pacific (R = 4 · 108 Ωm2)

Here, R stands for depth-integrated resistivity (transversal resistance) of the upper 100 km, representing the lithosphere. Figure 1(b) shows the 1-D conductivity sections (b), (e) and (f).

2.2 Derivation of the source model

A major geomagnetic storm, which had its maximum on November 20, 2003 with amplitudes of about 300 nT at Earth’ surface, is used as basis to construct a spatio-temporal model of the magnetospheric source. We have selected this storm due to its classical temporal form with clearly distinguishable main and recovery phases. For a ten-day time segment starting on November 18, 2003, we assembled minute mean magnetic data of 72 worldwide distributed observatories, situated at geomagnetic latitudes equatorward of ±55° (cf. Fig. 1(a)). What follows is an explanation how we derive the spatio-temporal structure of the source using these data.

We start with removing the mean value and a linear trend from the magnetic data. As all subsequent computations are done in frequency domain, we perform a Fourier transformation of the horizontal components of the data and obtain  . Here a is Earth’s mean radius and ω is angular frequency. Frequencies range between the Nyquist frequency of two minutes and the length of the time segment, i.e. ten days. Next we estimate the spatial structure of the impressed source. In frequency domain, Maxwell’s equations (1)–(2) read

. Here a is Earth’s mean radius and ω is angular frequency. Frequencies range between the Nyquist frequency of two minutes and the length of the time segment, i.e. ten days. Next we estimate the spatial structure of the impressed source. In frequency domain, Maxwell’s equations (1)–(2) read

Here time dependence is accounted for by e−iωt. Note that the dependence of B, E and jext on ω is omitted but implied. Equation (3) above Earth’s surface (in an insulating atmosphere and outside the source) reads

allowing the derivation of the magnetic field B in this region from the magnetic potential V,

By using the solenoidal property of the magnetic field,

the potential V satisfies Laplace’s equation

The general solution of Eq. (8) can be represented as a sum of external and internal parts, V = Vext + Vint. The external part is (in spherical coordinates) given by

Here  is a complex-valued function of ω, and the spherical harmonics are

is a complex-valued function of ω, and the spherical harmonics are

where  are Schmidt quasi-normalized associated Legendre polynomials. We avoid a discussion on Vint, since it is not relevant for the further development. It is obvious that the external part of the magnetic field (above Earth’s surface) has the form Bext = −∇Vext.

are Schmidt quasi-normalized associated Legendre polynomials. We avoid a discussion on Vint, since it is not relevant for the further development. It is obvious that the external part of the magnetic field (above Earth’s surface) has the form Bext = −∇Vext.

Now we are equipped to introduce a formula for the impressed current jext in Eq. (3) in terms of the coefficients  . It reads

. It reads

with

where δ denotes Dirac’s delta function, e

r

, e

ϑ

and e

φ

are unit vectors of the spherical coordinate system, and  is a short expression for the double sum in Eq. (9). The impressed current jext flows in a thin shell at r = b ≥ a and produces exactly the external magnetic field Bext in the region a ≤ r < b. Note that b does not represent the distance from the centre of the Earth to the actual magnetospheric source; see Appendix G of Kuvshinov and Semenov (2012) for details.

is a short expression for the double sum in Eq. (9). The impressed current jext flows in a thin shell at r = b ≥ a and produces exactly the external magnetic field Bext in the region a ≤ r < b. Note that b does not represent the distance from the centre of the Earth to the actual magnetospheric source; see Appendix G of Kuvshinov and Semenov (2012) for details.

By letting b approach a infinitesimally, i.e. setting b = a+, we can represent jext as

with

We solve Maxwell’s equations for each  , i.e.

, i.e.

By exploiting the linearity of Maxwell’s equation with respect to the source, we can represent, with the use of Eq. (13), the horizontal components of B at a ground-based observatory j as the sum of “unit” magnetic fields  scaled by the external coefficients

scaled by the external coefficients  that we want to determine:

that we want to determine:

We remark here that we work with horizontal component only, since they are less influenced by conductivity heterogeneities than the radial component.

Finally we estimate the external coefficients  by fitting the available data from the global net of observatories using the system of equations (17). We use an iteratively re-weighted least squares algorithm (e.g. Aster et al., 2005) to assure the stability of the solution.

by fitting the available data from the global net of observatories using the system of equations (17). We use an iteratively re-weighted least squares algorithm (e.g. Aster et al., 2005) to assure the stability of the solution.

Two comments are relevant at this point. First, note that the source of geomagnetic storm variations is assumed to be large-scale (at least at non-polar latitudes), and therefore external coefficients of relatively low n and m (≤ 3) are used to describe its spatial structure. Second, to solve numerically Maxwell’s equations (15)–(16), i.e. to calculate  and

and  at Earth’s surface on a 1° × 1° mesh, an integral equation approach (Kuvshinov, 2008) is used. Values of

at Earth’s surface on a 1° × 1° mesh, an integral equation approach (Kuvshinov, 2008) is used. Values of  at observatory locations are obtained by interpolation of the results obtained on the 1° × 1° mesh.

at observatory locations are obtained by interpolation of the results obtained on the 1° × 1° mesh.

An inverse Fourier transformation of the recovered coefficients yields their respective time series, which are depicted in Fig. 2. Note that in time domain, the depicted external coefficients correspond to an expansion of the magnetic potential V (at Earth’s surface) in the conventional form of cosine and sine functions,

As expected, the storm is mainly characterized by the coefficient  , apparent from a comparison with the Dst-index (cf. first plot of Fig. 2). The amplitude of the main event decreases with increasing n and m. The periodic Sq variations are, on the other hand, well visible in higher degree harmonics.

, apparent from a comparison with the Dst-index (cf. first plot of Fig. 2). The amplitude of the main event decreases with increasing n and m. The periodic Sq variations are, on the other hand, well visible in higher degree harmonics.

Source model: Time series of the recovered external coefficients  of the expansion of the magnetic potential in terms of spherical harmonics during the chosen geomagnetic storm (in nT). Days are relative to November 18, 2003. The green line in the first plot indicates the (negative) Dst-index for the considered storm. Note that the mean values of all coefficients (and of Dst) have been removed.

of the expansion of the magnetic potential in terms of spherical harmonics during the chosen geomagnetic storm (in nT). Days are relative to November 18, 2003. The green line in the first plot indicates the (negative) Dst-index for the considered storm. Note that the mean values of all coefficients (and of Dst) have been removed.

The presented scheme was used and verified before by Olsen and Kuvshinov (2004). The fit of our least-squares analysis (Eq. (17)) is shown in Fig. 3 by a comparison between the observed and calculated horizontal components of B at two observatories. As expected, the fit at the inland observatory Lanzhou/China (LZH, distance to the closest coast 1500 km) is slightly better than the fit at the coastal observatory Hermanus/South Africa (HER, distance to the coast <1 km). Note that the red graphs in Fig. 3 were obtained with model (a).

2.3 Calculation of the electric field

Once the external coefficients  are estimated, one can readily calculate—exploiting again the linearity of Maxwell’s equations with respect to the source—the electric field at any location on Earth’s surface as

are estimated, one can readily calculate—exploiting again the linearity of Maxwell’s equations with respect to the source—the electric field at any location on Earth’s surface as

A subsequent inverse Fourier transformation yields the time series of the electric field. It is noteworthy that the estimation of the geoelectric field for a different storm does not require a renewed solution of Maxwell’s equation. Only an estimation of  using Eq. (17) is necessary.

using Eq. (17) is necessary.

3. Results

3.1 Time series of the electric field at observatory locations

Figures 4 and 5 show the modelled time series of both horizontal components of E at the coastal observatory Hermanus (Fig. 4) and the inland observatory Lanzhou (Fig. 5). Solutions are shown for models (a) and (b), cf. Section 2.1. The choice of these models will be justified in Section 3.2. We make the following observations:

-

The electric field is subject to high-frequency oscillations during the geomagnetic storm, a clear peak phase (as usually observed for the magnetic field, cf. Fig. 3) is in general not recognizable.

-

1-D modelling yields peak amplitudes of about 50 mV/km for both components in LZH. Peak amplitudes in HER are about 50 mV/km for E φ and about 20 mV/km for E ϑ . 1-D modelling here implies the use of the local normal 1-D structure of the 3-D model (including the local conductance of the surface shell S, cf. Fig. 1(a)) and an individual solution of Maxwell’s equations at each grid point according to the methodology first presented by Srivastava (1966).

-

3-D modelling increases the amplitudes of both field components by roughly a factor 2 in HER, but has only minor effects in LZH.

-

An increase in lithosphere resistivity from 300 Ωm to 3000 Ωm has virtually no effect for the 1-D modelling results and only minor effects for the 3-D modelling results obtained in LZH. However, both field components obtained with 3-D modelling in HER are amplified, roughly by a factor 1.5.

3.2 Snapshots of the global pattern of the electric field

In order to compare the results obtained in models with different 1-D sections and thus to examine the influence of the conductivity stratification, snapshots of the global pattern appear more suitable than time series at selected sites due to the high-frequency oscillations of the electric field. Snapshots of E ϑ obtained in the six models described in Section 2.1 are presented in Fig. 6. Note that the numbering of the panels coincides with the numbering of the models in Section 2.1. All snapshots shown in Fig. 6 (and in subsequent figures) are taken at 17:00 UTC on November 20, 2003. This is in the build-up phase of the storm, i.e. prior to the peak magnetic phase.

The results obtained in models (a) and (c) are very similar. As both models have the same lithosphere conductivity, but a different 1-D stratification at greater depths, we conclude that the conductivity structure at depths greater than 100 km has only minor effects on the field pattern. The same conclusions can be made when comparing the results obtained in models (b) and (d). The field pattern obtained in model (e) (the original model derived by Baba et al. (2010) for the Philippine Sea) is similar to those obtained in models (a) and (c), but amplitudes appear to be slightly lower. Similarly, the pattern obtained in model (f) (the original model derived by Baba et al. (2010) for the North Pacific) is slightly less pronounced than the patterns obtained in models (b) and (d), and amplitudes are slightly lower. We attribute this difference to the increase in conductivity at shallow depths in the models derived by Baba et al. (2010) (cf. Fig. 1(b)).

A cross-comparison of both rows in Fig. 6 indicates that stronger and more pronounced fields are obtained in models with larger transversal resistance of the lithosphere. As the differences between the rows are significantly larger than those within each row, we conclude that our basic models (a) and (b) are good representatives and will thus in the following concentrate on the results obtained in models (a) and (b). Note that a comparison of E φ in the various models leads to the same conclusions, as well as the examination of snapshots at different instants.

We are especially interested in investigating the effects arising from the laterally non-uniform surface layer S. To this purpose, we present results in form of the “anomalous” electric field, which is computed as difference between our 3-D modelling results and results obtained in a “local 1-D” model. Local 1-D modelling here implies the use of the local normal 1-D structure of the 3-D model (including the local conductance of the surface shell S) and a solution of Maxwell’s equations separately performed at each grid point. Expressions for the (frequency domain) electric field emerging due to induction by a source of our type in 1-D conductivity models are presented in Appendix H of Kuvshinov and Semenov (2012).

Snapshots of the anomalous E ϑ and E φ for the same instant as in Fig. 6, computed in models (a) and (b), are presented in Fig. 7. The black latitude-parallel lines through North America and Australia indicate the profiles of electric field versus longitude that are drawn in Fig. 8. We make the following observations:

-

As expected, the anomalous field is very small inside continents and oceans, but pronounced in regions where conductance varies laterally on short scales, especially at the coasts.

-

Largest amplitudes are observed at long east and west coasts, e.g. the Americas or southern Africa. This reflects the geometry of the source (the magnetospheric ring current).

-

An increase of lithosphere resistivity from 300 Ωm to 3000 Ωm leads to an amplification of the components of the anomalous electric field by roughly a factor 2 at coastal sites.

-

The penetration width of the anomalous field is also governed by lithosphere resistivity. Dependent on the site, massive enhancements are observed up to 400 km inland in the case of a 300 Ωm lithosphere and up to 600 km inland in the more resistive case (Fig. 8; note that 1° of longitude corresponds to 100 km in the profile through Australia and to 85 km in the profile through North America).

-

In latitude-parallel profiles through continents, the anomalous E φ exhibits an axial symmetry, while the anomalous E ϑ is anti-symmetric. This observation confirms previous results by Kuvshinov et al. (1999) obtained in simplified conceptual models. Note that there is no enhancement of E ϑ at the Australian west coast for the chosen moment, cf. Fig. 8.

Snapshots of the modelled anomalous electric field (left column: E φ , right column: E ϑ , both in mV/km) at 17:00 UTC on November 20, 2003, computed in models (a) (top row) and (b) (bottom row). The black bars through North America and Australia denote the profiles shown in Fig. 8.

Profiles of the modelled anomalous electric field (left column: E φ , right column: E ϑ , both in mV/km) through North America and Australia (see also Fig. 7) at 17:00 UTC on November 20, 2003. The black dashed lines mark the coast.

Our results stress the need of 3-D modelling in an environment with large lateral variations in conductivity. The amplifications observed at coasts are at least on the same level as the maximum amplitudes obtained in 1-D models. As previously shown in Fig. 4, using a 1-D model might results in an underestimation of the peak amplitudes of the geoelectric field during a geomagnetic storm by a factor 2–3 at coastal sites. Due to the high temporal variability of the geoelectric field, coastal enhancements vary significantly during a geomagnetic storm.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1 Summary

We have presented a numerical scheme for a time domain estimation of the global electric field induced by a geomagnetic storm with realistic spatio-temporal structure, derived from measurements of the horizontal component of the magnetic field at worldwide distributed observatories. A conductivity model of Earth’s interior with a realistic laterally heterogeneous surface layer representing oceans and continents was used.

The results could be obtained within a few hours, if the observatory data were available and pre-processed (edited, checked for consistency etc.). It is noteworthy that this estimate does not depend on the complexity and resolution of the 3-D conductivity model, since the responses for induction in a given 3-D model by elementary sources (in case of a geomagnetic storm described by spherical harmonics) can be calculated beforehand and archived. To obtain the geoelectric field for a specific storm, it is just necessary to reconstruct the spatio-temporal form of the external source responsible for this storm and to convolve the source field with the precomputed 3-D responses. We believe that our numerical scheme would be a useful tool to estimate quantitatively the space weather hazard associated with excessive GIC arising in ground-based conductor networks (such as power lines) during major geomagnetic storms.

4.2 Effect of oceans and lithosphere

Model studies based on our numerical scheme revealed substantial differences between the electric fields generated in 3-D and 1-D models, even if the 1-D model makes use of the local vertical conductivity structure. As expected, the differences are mainly marked at the coasts. The anomalous electric field, computed as difference between the electric fields obtained in 3-D and 1-D models, can penetrate up to more than 500 km inland (depending on the site and the local conductivity structure). Anomalous amplitudes are at least as large as the amplitudes calculated in a 1-D model. Peak amplitudes of a geomagnetic storm at coastal sites are hence underestimated by a factor 2–3 when using a 1-D model. The 3-D modelling results state that coastal areas are in danger of experiencing electric field amplitudes of up to 200 mV/km during a typical magnetic storm. Long east and west coasts like the Americas, southern Africa or Australia and narrow land bridges like Panama seem to be especially endangered.

The resistivity of the lithosphere is a critical parameter when estimating amplitudes of the electric field. Resistivities of 300 Ωm and 3000 Ωm, representing realistic boundary values for Earth’s lithosphere, were tested in this study. Lithosphere resistivity mainly affects the electric field at coastal sites. The amplitudes of the anomalous electric field were doubled in the model with a lithosphere of 3000 Ωm, and the “coastal region”, in which the anomalous field shows enhanced amplitudes, was significantly wider. The influences of the conductivity distribution at greater depths and the precise stratification within the lithosphere on the results were minor in comparison with the integrated lithosphere resistivity.

According to our modelling results, a precise estimate of the lithosphere resistivity in the region of interest is crucial in order to obtain a trustworthy estimate of the actual electric field. In this study, we considered a model with a lithosphere of laterally uniform thickness and resistivity. While the chosen lithosphere thickness of 100 km agrees with the global average, it is well-known that lithosphere thickness is very variable on Earth and ranges from few km at mid-ocean ridges to several 100 km below old continental shields. The choice of a laterally uniform lithosphere is thus a limitation of our work; it was however necessary, since thickness and resistivity of the lithosphere are poorly resolved on a global scale. We want to stress in this context that the numerical solution discussed in this paper is fully 3-D and thus can readily adopt models with a laterally variable lithosphere once reliable information about such variability is available.

4.3 Estimates of the electric field at polar latitudes

In this paper, we discussed the geoelectric field induced by a large-scale magnetospheric source that dominates in mid-latitudes. However, it is well known that one can expect larger signals in polar regions due to substorm geomagnetic disturbances (Pirjola and Viljanen, 1994). The recovery of the spatio-temporal structure of the auroral ionospheric source, which is responsible for this activity, is more challenging due to the large variability of the auroral source both in time and space.

One of the ways to determine realistic auroral currents on a semi-global scale (in the whole polar cap) consists of collecting the data from high-latitude geomagnetic observatories and polar magnetometer arrays (e.g. IMAGE and MIRACLE arrays in Scandinavia, DTU and MAGIC arrays in Greenland, CARISMA array in Canada etc.) and then reconstructing the auroral current, for example by exploiting an approach based on elementary current systems (e.g. Amm, 2001; Sun and Egbert, 2012). Note that this approach was used by Pulkkinen and Engels (2005), who analysed the influence of 3-D induction effects on ionospheric currents during geomagnetic substorms.

Once the auroral source is quantified, a similar numerical scheme as described above, however with two modifications, can be implemented in order to calculate the geoelectric field caused by a geomagnetic substorm. One modification concerns the description of the substorm source— instead of using a spherical harmonics representation, one can mimic the auroral ionospheric current by elementary current systems. Another modification applies to the 3-D conductivity model. Since substorm magnetic variations are characterized by periods between a few tens of seconds and tens of minutes, one cannot exploit a model in which the surface layer is approximated by a thin shell, as it was done in this paper. The variable thickness of this layer is important in this period range, thus a full 3-D model (including bathymetry) should be considered. However, as mentioned in Section 4.1, the complexity and resolution of the 3-D conductivity model has no effect on the computational cost of the source modelling for a specific substorm. As in the case of a large-scale geomagnetic storm, a model of the electric field due to a specific substorm for the whole polar cap could be obtained within a few hours when using a standard workstation for computations. Note again that this estimate does not account for the efforts of collecting and pre-processing the data and for the 3-D calculations of the magnetic field due to elementary sources.

Semi-global estimates of the geoelectric field induced by a realistic geomagnetic substorm in a realistic 3-D conductivity model accounting for bathymetry and non-uniform lithosphere will be the subject of a subsequent publication.

References

Amm, O., The elementary current method for calculating ionospheric current systems from multisatellite and ground magnetometer data, J. Geophys. Res., 106, 24843–24855, 2001.

Aster, R. C., B. Borchers, and C. H. Thurber, Parameter Estimation and Inverse Problems, Elsevier Academic Press, 2005.

Baba, K., H. Utada, T. Goto, T. Kasaya, H. Shimizu, and N. Tada, Electrical conductivity imaging of the Philippine Sea upper mantle using seafloor magnetotelluric data, Phys. Earth. Planet. Inter., 183, 44–62, 2010.

Beamish, D., T. D. G. Clark, E. Clarke, and A. W. P. Thomson, Geomagnetically induced currents in the UK: Geomagnetic variations and surface electric fields, J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys., 64, 1779–1792, 2002.

Cox, C. J., Electromagnetic induction in the oceans and inferences on the constitution of the earth, Geophys. Surv., 7, 137–156, 1980.

Everett, M. E., S. Constable, and C. G. Constable, Effects of near-surface conductance on global satellite induction responses, Geophys. J. Int., 153, 277–286, 2003.

Fainberg, E. B., Electromagnetic induction in the world ocean, Geophys. Surv., 4, 157–171, 1980.

Gilbert, J., Modeling the effect of the ocean-land interface on induced electric fields during geomagnetic storms, Space Weather, 3, doi:10.1029/2004SW000120, 2005.

Kappenman, J., L. Zanetti, and W. Radasky, Geomagnetic storms can threaten electric power grid, Earth in Space, 9, 9–11, 1997.

Kuvshinov, A., 3-D Global induction in the oceans and solid Earth: recent progress in modeling magnetic and electric fields from sources of magnetospheric, ionospheric and oceanic origin, Surv. Geophys., 29, 139–186, 2008.

Kuvshinov, A. and N. Olsen, A global model of mantle conductivity derived from 5 years of CHAMP, Ørsted, and SAC-C magnetic data, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, doi:10.1029/2006GL027083, 2006.

Kuvshinov, A. and A. Semenov, Global 3-D imaging of mantle electrical conductivity based on inversion of observatory C-responses I. An approach and its verification, Geophys. J. Int., 189, doi:10.1111/j.1365–246X.2011.05349.x, 2012.

Kuvshinov, A. V., D. B. Avdeev, and O. V. Pankratov, Global induction by Sq and Dst sources in the presence of oceans: bimodal solutions for nonuniform spherical surface shells above radially symmetric Earth models in comparison to observations, Geophys. J. Int., 137, 630–650, 1999.

Laske, G. and G. Masters, A global digital map of sediment thickness, Eos Trans. AGU, 78, F483, 1997.

Love, J. J., Magnetic monitoring of Earth and space, Physics Today, 61, 31–37, 2008.

Manoj, C, A. Kuvshinov, S. Maus, and H. Luehr, Ocean circulation generated magnetic signals, Earth Planets Space, 58, 429–437, 2006.

Olsen, N. and A. Kuvshinov, Modeling the ocean effect of geomagnetic storms, Earth Planets Space, 56, 525–530, 2004.

Parkinson, W. D. and F. W. Jones, The geomagnetic coast effect, Rev. Geophys., 17, 1999–2015, 1979.

Pirjola, R., Geomagnetically induced currents during magnetic storms, IEEE Trans Plasma Sci, 28, 1867–1873, 2000.

Pirjola, R. and A. Viljanen, Geomagnetically induced currents in the Finnish high-voltage power system, a geophysical review, Surv. Geophys., 15, 383–408, 1994.

Pulkkinen, A. and M. Engels, The role of 3-D geomagnetic induction in the determination of the ionospheric currents from the ground geomagnetic data, Ann. Geophys., 23, 909–917, 2005.

Pulkkinen, A., M. Hesse, M. Kuznetsova, and L. Rastatter, First principles modeling of geomagnetically induced electromagnetic fields and currents from upstream solar wind to the surface of the Earth, Ann. Geophys., 25, 881–893, 2007.

Rikitake, T. and Y. Honkura, Developments in Earth and planetary sciences, in Solid Earth Geomagnetism, vol. 5, edited by Rikitake, T., Terra Scientific Publishing Company, 1985.

Srivastava, S. P., Theory of the magnetotelluric method for a spherical conductor, Geophys. J. R. Astron. Soc., 11, 373–387, 1966.

Sun, J. and G. Egbert, Spherical decomposition of electromagnetic fields generated by quasi-static currents, Int. J. Geomath., 3, 279–295, 2012.

Thomson, A. W. P., A. J. McKay, E. Clarke, and S. J. Reay, Surface electric fields and geomagnetically induced currents in the Scottish Power grid during the 30 October 2003 geomagnetic storm, Space Weather, 3, doi:10.1029/2005SW000156, 2005.

Thomson, A. W. P., A. J. McKay, and A. Viljanen, A review of progress in modelling of induced geoelectric and geomagnetic fields with special regard to induced currents, Acta Geophys., 57, 209–219, 2009.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the staff of the geomagnetic observatories who have collected and distributed the data. We thank Dr. Alan Thomson for discussion on the manuscript and Dr. Ikuko Fujii and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments. This work has been supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation under grant No. 2000021-140711/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Püthe, C., Kuvshinov, A. Towards quantitative assessment of the hazard from space weather. Global 3-D modellings of the electric field induced by a realistic geomagnetic storm. Earth Planet Sp 65, 1017–1025 (2013). https://doi.org/10.5047/eps.2013.03.003

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5047/eps.2013.03.003