Published online Dec 15, 2021. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v13.i12.2038

Peer-review started: February 15, 2021

First decision: March 15, 2021

Revised: March 24, 2021

Accepted: October 15, 2021

Article in press: October 15, 2021

Published online: December 15, 2021

Globally, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a frequently diagnosed malignancy with rapidly increasing incidence and mortality rates. Unfortunately, many of these patients are diagnosed in the advanced stages when locoregional treatments are not appropriate. Before 2008, no effective drug treatments existed to prolong survival, until the breakthrough multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sorafenib was developed. It remained the standard treatment option for advanced HCC for 10 years, with a battery of other candidate drugs in clinical trials failing to produce similar efficacy results. In 2018, the REFLECT trial introduced another multi-TKI, lenvatinib, which has non-inferior overall survival compared with sorafenib. Thus, offering patients and their treating physicians two effective treatment options. Recently, immunotherapy-based drugs, such as atezolizumab and bevacizumab, have shown promising results in patients with unresectable HCC. This review summarizes clinical trial and real-world data studies of sorafenib and lenvatinib in patients with unresectable HCC. We offer guidance on the optimal choice between the two treatments and discuss the potential of immunotherapy-based combination; when more data become available, this will likely make the choice between sorafenib and lenvatinib somewhat obsolete.

Core Tip: Recently, an immunotherapy-based combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab was shown to prolong survival compared to sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma patients who did not receive prior therapy. In addition, the combination of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab has yielded promising results in the same patient setting. This review article summarizes the results obtained with sorafenib and lenvatinib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in pivotal clinical trials and real-world studies. We offer guidance on the optimal choice between sorafenib or lenvatinib in an individual patient and discuss the immunotherapy-based combination, which will likely make the choice between sorafenib and lenvatinib somewhat obsolete.

- Citation: Alqahtani SA, Colombo MG. Current status of first-line therapy, anti-angiogenic therapy and its combinations of other agents for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma . World J Gastrointest Oncol 2021; 13(12): 2038-2049

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v13/i12/2038.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v13.i12.2038

Currently, liver cancer ranks as the seventh most common cancer type in the world, being the fourth most common cause of cancer-related death[1]. The vast majority of these liver cancers (approximately 80%) arise from hepatocytes and are referred to as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[2]. Over the last decades, the global incidence of HCC has been increasing, with a 75% incidence increase of newly diagnosed HCC cases from 1990 to 2015[3]. Risk factors for developing HCC consist of viral hepatitis, extreme alcohol intake, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)[2]. Furthermore, obesity increases the risk of developing NAFLD, and given the ever-increasing obesity epidemic in many parts of the world, the significance of NAFLD-related HCC is predicted to have profound effects in the coming years[4].

For patients with initial-stage HCC, curative therapy strategies, such as liver resection, liver transplantation, or radiofrequency ablation, can still provide long-term survival[2,5]. However, many HCC patients receive their diagnosis at progressive stages of the disease when locoregional treatment is no longer an option. When not treated, patients with advanced-stage HCC have a very poor prognosis, with a median overall survival (OS) of 9 mo and a 6-mo OS of 56.6%[6]. Until 2008, not a single effective systemic treatment option was available for these patients, an unparalleled situation in oncology. In fact, advanced HCC proved to be notoriously difficult to treat. HCC is not only a very chemo-resistant tumor type, but the constant threat of declining liver function often compromises an effective treatment. Over the last decades, improved insights into the molecular processes that initiate and promote the tumor progression in HCC have facilitated the development of novel molecular treatment modalities that specifically target these disrupted molecular pathways.

In 2008, the multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sorafenib became the first effective systemic therapy for patients with advanced HCC with a preserved liver function[7]. Following its successful introduction into the treatment paradigm for advanced HCC, several other targeted drugs were tested in this setting. Unfortunately, this resulted in a decade of disappointing phase III randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Until 2017, the oral multi-TKI regorafenib reported increased survival rates in patients who received sorafenib[8]. Shortly thereafter, the multi-TKIs cabozantinib and ramuci

In recent years, the growing interest in immune checkpoint inhibition as a new pillar of the cancer treatment paradigm has also spurred the evaluation of these drugs in patients with unresectable HCC. Clinical trials using these immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in monotherapy demonstrate only a moderate clinical benefit[12,13]. In contrast, RCTs evaluating combinations of a TKI and an ICI have generated more convincing results. In fact, results of the phase III IMbrave150 trial recently highlighted that atezolizumab plus bevacizumab had a significantly prolonged OS compared to sorafenib in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced HCC[14]. Furthermore, new data are emerging for other first-line ICI-TKI combinations (e.g., pembrolizumab-lenvatinib). This review summarizes the results obtained from clinical trials and real-world studies of sorafenib and lenvatinib in patients with unresectable HCC. We offer guidance on the optimal choice between sorafenib or lenvatinib in an individual patient and discuss the potential of immunotherapy-based combinations, which, with more data, will likely make a choice between sorafenib and lenvatinib somewhat obsolete.

Sorafenib is an oral multi-TKI that checks and arrests several tyrosine kinases involved in tumor angiogenesis, progression, and apoptosis. It inhibits both vascular endo

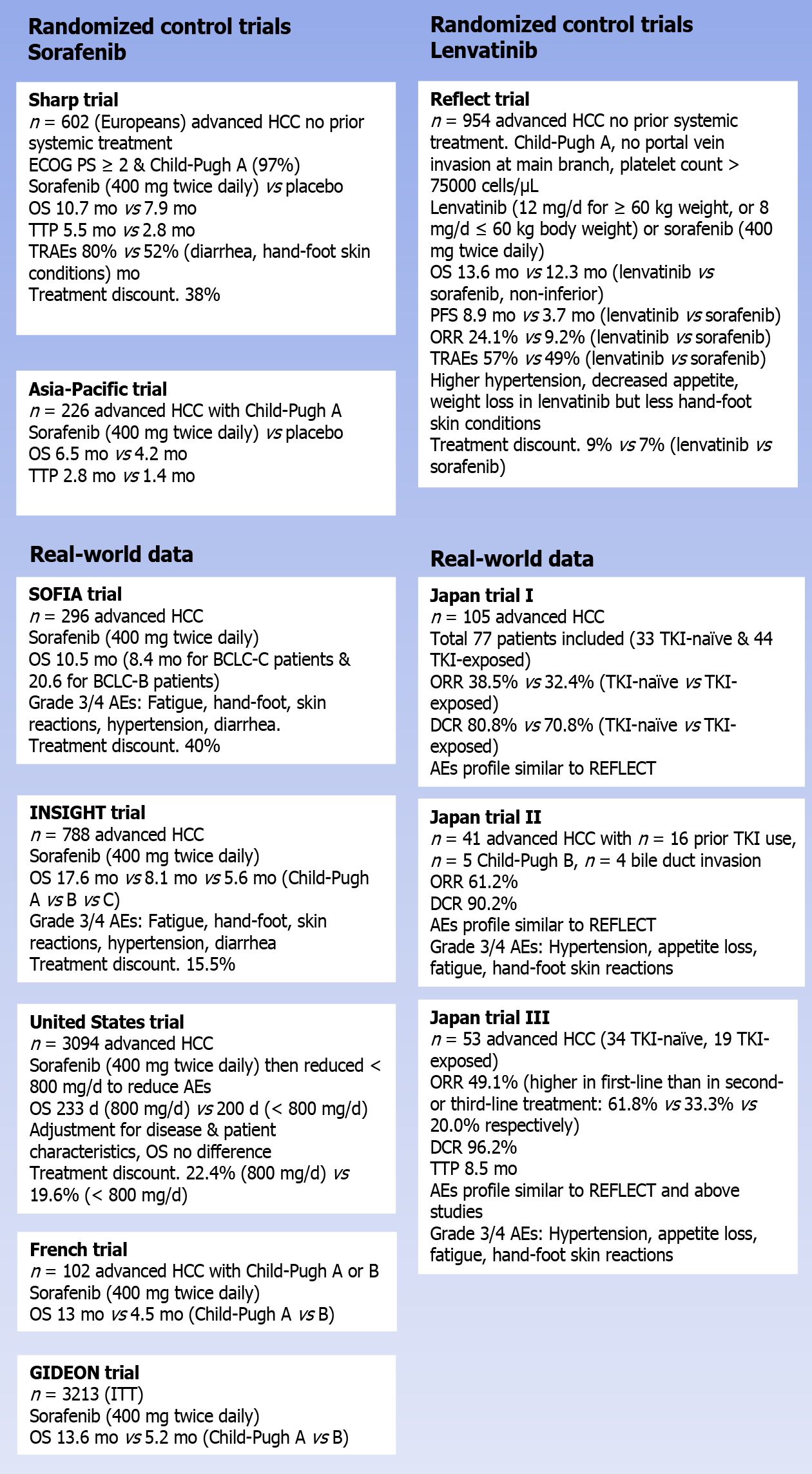

In the phase III SHARP trial, 602 (mainly European) patients with advanced HCC, who did not receive prior systemic treatment, were randomly assigned to receive either sorafenib (400 mg twice daily) or placebo. In order to be eligible for the trial, patients had to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of ≥ 2 and have a preserved liver function (Child-Pugh class A)[7]. The median age of patients in the trial was 65 years, more than 80% had Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C disease, and the vast majority (97%) were rated as Child-Pugh A at baseline. The study reached its primary endpoint by proving a significant OS benefit for sorafenib compared to placebo, with a median OS of 10.7 and 7.9 mo, respectively [hazard ratio (HR) 0.69; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.55-0.87; P < 0.001]. Also, in terms of the time to radiological progression, sorafenib outperformed the placebo (median: 5.5 mo vs 2.8 mo; HR 0.58; 95%CI: 0.45-0.74; P < 0.001). Objective response rates (ORR) were rare in both arms of the study, with only 2% partial responses with sorafenib compared to 1% with placebo (no complete responses were reported). However, looking at the disease control rate (DCR), a significant benefit was seen for sorafenib compared to placebo (43% vs 32%; P = 0.002)[7]. In the SHARP trial, the incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) was reported at 80% with sorafenib compared to 52% with placebo. The most common grade 3/4 TRAEs of sorafenib were diarrhea (8% with sorafenib vs 2% with placebo; P < 0.001) and hand-foot skin reactions (8% vs 1%; P < 0.001). Despite the relatively low rate of high-grade TRAEs, the rate of therapy discontinuations due to adverse events (AEs) was high at 38%.

The second pivotal trial with sorafenib in patients with progressive HCC was conducted in the Asia-Pacific region and yielded fairly similar results[16]. In that trial, a total of 226 advanced HCC patients with a Child-Pugh A liver score were randomly assigned (2:1) to receive either sorafenib (400 mg twice daily) or placebo. Sorafenib also showed a significantly prolonged OS compared to placebo, with a median OS of 6.5 and 4.2 mo for sorafenib and placebo, respectively (HR 0.68; 95%CI: 0.50-0.93; P = 0.014). In addition to this, patients who received sorafenib had a significantly longer time to progression (TTP) compared to patients treated with placebo (median 2.8 mo vs 1.4 mo; HR 0.57; 95%CI: 0.42-0.79; P = 0.0005)[16].

In the years following the registration of sorafenib for patients with advanced HCC, several studies were set up to evaluate the performance of sorafenib in a real-world setting. In the Italian SOFIA study, 269 advanced HCC patients were treated with sorafenib (400 mg twice daily), resulting in a median OS of 10.5 mo (8.4 mo for patients with BCLC-C disease and 20.6 mo for BCLC-B patients)[17]. The most common grade 3/4 AEs reported in SOFIA were fatigue (25%), hand-foot skin reactions (9%), hy

The prospective, non-interventional INSIGHT trial also evaluated the safety and efficacy of sorafenib in real-world clinical practice. In this study, including a safety set of 788 HCC patients, the rate of TRAE discontinuations was much lower than in SHARP and SOFIA, as only 15.5% of patients discontinued their therapy because of unacceptable toxicity[18]. A possible explanation for this lower rate could be the fact that this study was reported a decade after the introduction of sorafenib. Thus, it is likely that the increased experience of physicians with this agent and the increased knowledge on how to deal with its toxicity profile ultimately resulted in this lower rate of TRAE discontinuation.

Similarly, a large retrospective study from the United States reported lower rates of TRAE discontinuations with sorafenib than those reported in SHARP. In that study, published in 2017, a total of 3094 advanced HCC patients received sorafenib at the normal dose of 800 mg per day. Of them, only 22.4% had to discontinue their therapy for reasons of toxicity[19]. In an attempt to reduce further the TRAE drop-out, the possibility of introducing sorafenib at a lower dose (< 800 mg/d) was explored, resulting in a decreased pill burden that was less expensive. In addition to this, there were fewer treatment discontinuations due to safety/toxicity concerns (19.6%). With the standard dosing, the median OS reported in this cohort was 233 d (approximately 7-8 mo), which is in line with the SHARP trial[7,19]. Among patients who received a reduced dose of sorafenib, the median OS was shorter at 200 d. However, given the fact that patients who received the reduced dose were generally sicker than patients who were deemed to be eligible for the full dose, this comes as no surprise. When compensating for the differences in patient and disease characteristics between patients in the full and reduced dose cohort (propensity score-matched analysis), no difference in OS was found (HR 0.92; 95%CI: 0.83-1.01)[19].

Among the patients enrolled in these RCTs, many of them had a stable hepatic function with reference to Child-Pugh A disease (SHARP: 95% and Asia-Pacific study: 97%). However, in real-world settings, there are patients with hepatic dysfunction (Child-Pugh B or C), and for these, the RCTs do not provide a clear answer on the potential benefit of sorafenib. In this respect, real-world data can provide guidance to physicians. Not surprisingly, results of a French case-control study (n = 120) indicate that advanced HCC patients with a Child-Pugh A status have a better OS when they are treated with sorafenib than patients who have more advanced liver damage (Child-Pugh B), with a median OS of 13 and 4.5 mo, respectively (P = 0.0008)[20]. A similar observation was seen in the INSIGHT trial, where the median OS with sorafenib was reported as 17.6 mo for patients with a Child-Pugh A status, decreasing to 8.1 and 5.6 mo for patients with Child-Pugh B or C disease, respectively[18]. Finally, the observational GIDEON registry showed that Child-Pugh A patients have a longer OS when treated with sorafenib than patients with Child-Pugh B disease (median OS: 13.6 and 5.2 mo, respectively)[21]. However, the fact that Child-Pugh B patients do worse on sorafenib than patients with a preserved liver function should not be a reason to reserve sorafenib for patients with Child-Pugh A disease alone. In fact, GIDEON also shows that the overall safety profile and dosing strategy of sorafenib are similar across the different Child-Pugh subgroups[21]. In another prospective study by Leal et al[22], in a separate prospective score, specifically focusing on the use of sorafenib in Child-Pugh B patients, a median OS of 6.5 mo was reported, which was longer than historical controls for this population. In this study, sorafenib also proved to be tolerable, with a relatively low rate of TRAE discontinuations (27.7%)[22]. As such, these results highlight that selected Child-Pugh B patients may also derive benefit from treatment with sorafenib, with a manageable toxicity profile.

Overall, a large body of real-world data convincingly validate sorafenib as a safe and effective therapy option for patients with advanced HCC and confirm the results obtained in the pivotal RCTs. Furthermore, real-world data have also indicated that given adequate patient selection, sorafenib can also be safe and effective in patients who do not meet the strict inclusion criteria of the SHARP and Asia-Pacific trial.

Since its introduction as a treatment option for patients with advanced HCC, sorafenib has been evaluated against several other targeted agents. However, sunitinib did not prove to be better than sorafenib, and two non-inferiority studies testing brivanib and linifanib against sorafenib turned out to be negative[23]. In addition to this, the phase III SEARCH trial, assessing the potential benefit of adding erlotinib to sorafenib in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced HCC, also failed to show a benefit[24]. In the background of these numerous negative studies, the positive outcome of the phase III REFLECT trial in 2018, showing non-inferiority of lenvatinib to sorafenib as a first-line treatment for patients with unresectable HCC, came somewhat as a surprise[11].

Similar to sorafenib, lenvatinib is a multi-TKI. It primarily inhibits the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1–3, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1–4, KIT, and RET (Figure 1)[25]. In a single-arm phase II trial, including 46 patients with advanced HCC, lenvatinib at a fixed dose of 12 mg/d was found to have substantial clinical activity. With this regimen, a median OS of 18.7 mo was reported, with 37% of patients obtaining a partial response. However, this came at the cost of considerable toxicity, necessitating a dose reduction and treatment discontinuation in 74% and 22% of patients, respectively[26]. Further in-depth analyses of this trial revealed a close correlation between lenvatinib treatment discontinuation and body weight. Based on this finding, the investigators opted to use a weight-adapted lenvatinib dosing in the subsequent phase III trial.

In the randomized phase III REFLECT trial, a total of 954 patients who did not receive treatment for unresectable HCC were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either lenvatinib (12 mg/d for patients weighing ≥ 60 kg; 8 mg/d for patients weighing < 60 kg) or sorafenib (400 mg twice daily). In order to be eligible for the study, patients had to have a Child-Pugh A liver status and were not allowed to have portal vein invasion at the main portal branch. In addition, patients with a platelet count below 75000 cells/μL were excluded. The study’s primary outcome was to demonstrate non-inferiority for lenvatinib compared to sorafenib regarding the OS, with a non-inferiority margin of 1.08. The median age of the patients enrolled in REFLECT was 62 years; 69% had a body weight of ≥ 60 kg, and two-thirds came from Asia-Pacific regions. Extrahepatic spread at baseline was seen in 61% of the patients, while 21% exhibited macroscopic portal vein invasion (macroscopic portal vein invasion and/or extrahepatic spread in 70%). The majority of patients (79%) were classified as having BCLC stage C disease, and 57% had more than one involved disease site. Most of the patient and disease characteristics were well-proportioned between both arms, with some important exceptions. In fact, the number of patients with a hepatitis C etiology was higher in the sorafenib arm than in patients treated with lenvatinib (19% vs 26% for lenvatinib and sorafenib, respectively), while the opposite was true for the proportion of hepatitis B-related HCC (53% vs 48%). Finally, a marked imbalance was seen in the number of patients with an AFP level of ≥ 200 ng/mL (46% vs 39%)[11].

The median OS for patients treated with lenvatinib in the REFLECT trial was reported at 13.6 mo, which was shown to be non-inferior to the 12.3 median OS seen in patients who received sorafenib (HR 0.92; 95%CI: 0.79-1.06). Besides, lenvatinib induced a significant progression-free survival (PFS) than sorafenib. In fact, compared to sorafenib, the median PFS for patients treated with lenvatinib was more than twice as long as the median PFS obtained with sorafenib (7.4 vs. 3.7 mo; HR 0.66; 95%CI: 0.57-0.77; P < 0.0001). Importantly, lenvatinib was also shown to be associated with a significantly increased rate of ORR compared to sorafenib. With lenvatinib, an ORR of 24.1% was reported, while only 9.2% of sorafenib-treated patients obtained a partial or complete response (odds ratio; OR 3.13; 95%CI: 2.15-4.56; P < 0.0001) (Table 1)[11].

| Lenvatinib (n = 478) | Sorafenib (n = 476) | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Median OS | 13.6 mo | 12.3 mo | 0.92 (0.79-1.06) | |

| Median PFS | 7.4 mo | 3.7 mo | 0.66 (0.57-0.77) | P < 0.0001 |

| Median TTP | 8.9 mo | 3.7 mo | 0.63 (0.53-0.73) | P < 0.0001 |

| ORR | 24.1% | 9.2% | OR (95%CI): 3.13 (2.15-4.56) | P < 0.0001 |

| DCR | 75.5% | 60.5% | - |

With respect to safety, lenvatinib was found to be associated with a slightly increased rate of grade ≥ 3 treatment-emergent AEs compared to sorafenib (57% vs 49%). This difference was mainly fueled by a higher rate of grade ≥ 3 hypertension (23% vs 14%) and an increased rate of grade ≥ 3 decreased appetite (5% vs 1%) and grade ≥ 3 weight loss (8% vs 3%) among patients treated with lenvatinib. In contrast, lenvatinib was associated with a substantially lower incidence of hand-foot skin reactions (all grade: 27% vs 52%; grade ≥ 3: 3% vs 11%)[11]. The proportion of patients requiring a dose interruption (40% vs 32%), dose reduction (37% vs 38%), and treatment discontinuation (9% vs 7%) was similar in the lenvatinib and sorafenib arms.

Obviously, as lenvatinib only entered the HCC arena in 2018, the real-world evidence with this agent is more limited compared with sorafenib data. To date, the available real-world data with lenvatinib almost universally originate from Japan.

The largest real-world dataset for lenvatinib reported to date includes data from 105 unresectable HCC patients treated with lenvatinib across 48 clinics in Japan[27]. After excluding patients who started lenvatinib at a reduced dose and with a short ob

In a second study, a total of 41 patients with unresectable HCC were treated with lenvatinib. Interestingly, of these patients, 23 (56%) would not have been eligible for the REFLECT trial, mainly because of a prior history of TKI use (n = 16), a Child-Pugh B score (n = 5), and the presence of bile duct invasion (n = 4). In this cohort, lenvatinib was associated with an ORR of 61.0% and a DCR of 90.2%. Overall, 5 patients (12.2%) experienced a complete response to lenvatinib. Interestingly, both the ORR and the DCR did not differ between patients who met the REFLECT criteria or not (P = 0.83 and 0.79, respectively). In patients with a Child-Pugh B score, the ORR was 60% (3/5), while this was 100% in the 4 patients with bile duct invasion. With respect to safety, no major differences were seen between REFLECT eligible and ineligible patients, with a similar rate of grade ≥ 3 AEs. Lenvatinib in this cohort caused the following AEs most commonly: Hypertension (68.3%, grade ≥ 3 12.2%), appetite loss (68.3%; 2.4%), fatigue (58.5%; 0%), and hand-foot skin reactions (56.1%, 14.6%). As such, these real-world data demonstrate that lenvatinib induces a high early response rate with good to

A third Japanese real-world study yielded fairly similar results, in which 57 unresectable HCC patients were treated with lenvatinib, of whom 53 were eligible for response (34 TKI-naïve, 19 TKI-exposed). In this cohort, lenvatinib therapy resulted in an ORR of 49.1% (26/53) and a DCR of 96.2% (51/53). Of note, the ORR was higher in patients receiving lenvatinib in first-line (61.8%) compared to patients receiving a second- (33.3%) or third-line (20.0%) treatment. The median TTP in the entire cohort was reported at 8.5 mo, and also for this endpoint, the outcome was better when lenvatinib was used as a first-line treatment. In addition, this real-world study revealed that patients with a better liver functional reserve had a higher response rate to lenvatinib and a longer TTP. Similar to REFLECT, the most common AEs with lenvatinib were hypertension (54.7%, grade ≥ 3: 15.1%), fatigue (49.1%, 7.5%), and a decreased appetite (37.7%, 0%). Hand-foot skin reactions were reported in 26.4% of the patients (all grade 1/2)[29].

In a multi-center retrospective study, including 77 patients with advanced HCC, lenvatinib was associated with an ORR of 29.9% (similar to REFLECT) and a DCR of 77.9%. Interestingly, thyroid dysfunction and appetite loss were found to be associated with a worse and shorter PFS[30]. In this respect, Hiraoka et al[31] also identified appetite loss as a dismal prognostic factor for advanced HCC patients treated with lenvatinib[31]. As such, these AEs should be managed with care in patients treated with lenvatinib.

As illustrated above, robust RCT data and convincing real-world results have iden

The phase III REFLECT trial showed non-inferiority of lenvatinib compared to sorafenib and even demonstrated a numerically longer median OS in lenvatinib-treated patients compared to patients treated with sorafenib (13.6 mo vs 12.3 mo). This difference did not meet the statistical threshold to demonstrate superiority of lenvatinib compared to sorafenib. However, in a critical appraisal of REFLECT, as acknowledged by the authors, this lack of superiority might have been influenced by elements in the study design[32]. First of all, both the baseline AFP level and the presence of macrovascular invasion were not used as a stratification factor for the randomization in REFLECT. As a result, a higher proportion of patients in the lenvatinib arm had macrovascular invasion (23% vs 19%) or an elevated AFP level (≥ 200 ng/mL: 46% vs 39%)[11]. It is likely that this higher incidence of poor prognostic factors in the lenvatinib cohort had an influence on the survival outcome of these patients. Another demographic imbalance that might have influenced the trial outcome relates to the HCC etiology. In fact, a higher proportion of patients in the sorafenib arm had HCC with a hepatitis C etiology compared to the lenvatinib arm (19% vs 26%)[11]. This difference is of clinical importance given the fact that the treatment effect of sorafenib depends on the hepatitis status of patients, with the best OS prospects for patients with hepatitis C virus-positive HCC. A third and final element from REFLECT that might have diluted the OS benefit of lenvatinib is that patients with invasion of the main portal vein and patients with a disease bulk of more than 50% of the liver were excluded from the study. As a result, the trial selected patients who were more likely to be eligible for subsequent therapy after disease progression on the study drug. This hypothesis is confirmed by the high proportion of patients in both the lenvatinib arm (33%) and sorafenib arm (39%) who received some form of post-study anticancer therapy in REFLECT[11]. These subsequent therapies have likely prolonged the post-progression survival of patients in both treatment arms, diluting the potential OS benefit obtained with one of the two agents in the first-line setting. The fact that the median OS obtained with sorafenib in REFLECT was the longest ever reported with sorafenib in a large RCT further supports the idea that post-study therapies had an important influence on the OS analysis of this trial[7,11,16,23,24]. As such, several elements of the REFLECT trial design might have mitigated the true OS benefit of patients treated with lenvatinib vs sorafenib. However, it is important to underscore that these statistical speculations should only be seen as hypothesis-generating. This should not be used as an argument to claim a survival superiority of lenvatinib over sorafenib in the first-line treatment of advanced HCC patients.

As such, a critical evaluation of the OS analysis of REFLECT does not help physicians to make a choice between both TKIs in their clinical practice. Perhaps, more practical advice can be derived from the detailed subgroup analysis performed in the trial. In general, the effect of lenvatinib and sorafenib on OS was consistent across all the investigated subgroups. Nevertheless, some subgroups seemed to have a slightly better OS when treated with lenvatinib instead of sorafenib. With respect to HCC etiology, particularly patients with a hepatitis B virus infection seemed to derive a more pronounced OS benefit from lenvatinib compared to sorafenib (median OS: 13.4 mo vs 10.2 mo; HR 0.83; 95%CI: 0.68-1.02). Regional differences were also seen: While patients with a Western origin had a fairly similar median OS with lenvatinib and sorafenib (13.6 mo vs 14.2 mo), patients from Asia-Pacific displayed a numerically longer median OS with lenvatinib (13.5 mo vs 11.0 mo; HR 0.86; 95%CI: 0.72-1.02). Finally, the presence of macroscopic portal vein invasion and/or extrahepatic spread (median OS: 11.5 mo vs 9.8 mo; HR 0.87; 95%CI: 0.73-1.04) and a baseline AFP level ≥ 200 ng/mL (median OS: 10.4 mo vs 8.2 mo; HR 0.78; 95%CI: 0.63-0.98) seemed to be associated with a more pronounced treatment effect with lenvatinib[11].

As indicated earlier, lenvatinib was found to be superior to sorafenib in terms of response rate[11]. This finding can be used to make treatment decisions in clinical practice. It is well established that sorafenib mainly induces its survival benefit in patients with advanced HCC by stabilizing the disease. However, in some patients (e.g., patients with bulky disease), a tumor response may be warranted to alleviate symptoms. When faced with such a patient, lenvatinib is probably the better choice.

Both sorafenib and lenvatinib come with a specific toxicity profile, and these differences should be taken into account when opting for one of the two agents. For example, given the high incidence of hypertension reported with lenvatinib, it seems wise to avoid this agent in patients with baseline hypertension or other cardiovascular risk factors.

Finally, the treatment cost should be considered, especially in the context of the ever-increasing pressure on healthcare budgets. In this respect, two independent cost-effectiveness analyses demonstrate that lenvatinib is more cost-effective than sorafenib in the first-line treatment of patients with unresectable HCC[33,34].

As of now, no standard therapies are available for patients who encountered lenvatinib failure. Sorafenib can be considered in such cases, given that about one-fourth of patients in the REFLECT trial received sorafenib while taking lenvatinib as the first-line medication[35]. Recently, a Japanese pilot study has suggested the potential therapeutic benefit from ramucirumab after lenvatinib failure in HCC patients; nevertheless, another study with more patients could not confirm such benefits in the post-progression treatment[36,37].

Since 2008, sorafenib has been the long-standing standard of care in the first-line treatment for patients with unresectable HCC. It took until 2018, with the publication of the REFLECT trial, before an alternative for sorafenib became available. Recently, results presenting the potential benefits of immunotherapy-based combinations may bring in a crucial change in therapeutic strategies for patients with advanced HCC. In the phase III IMbrave 150 trial, atezolizumab anti-PD-L1) plus bevacizumab (anti-vascular endothelial growth factor) was compared to sorafenib as a first-line treatment of patients with advanced HCC. The atezolizumab-bevacizumab combination showed a significant and clinically meaningful OS improvement compared to sorafenib (median OS not reached vs 13.2 mo; HR 0.58; 95%CI: 0.42–0.79; P = 0.006). At the 12-mo landmark, 67.2% of patients in the combination arm were still alive, 12% more than the 54.6% OS rate seen with sorafenib at 12 mo. Besides, the median PFS was 6.8 mo vs 4.3 mo (atezolizumab-bevacizumab vs sorafenib; HR 0.59; 95%CI: 0.47–0.76; P < 0.0001). This combination regimen had an expected drug safety profile, with a late deterioration in patients’ quality of life[14]. Based on these findings, in May 2020, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved this combination for treating patients with unresectable HCC who had not previously received systemic treatment. In addition, the European Society for Medical Oncology updated its HCC guidelines and endorsed the atezolizumab-bevacizumab combination as a regimen that can be considered a first-line treatment option for advanced HCC patients[35]. While the groundbreaking outcome of the trial led to the approval of the new treatment in 16 countries, the same has been questioned for its generalizability, owing to the short duration of the trial follow-up and the lack of both safety and efficacy data in Western patients, in whom liver cancer has a different molecular profile than in Asian patients and in patients with metabolic tumors, autoimmune disorders, and transplanted organs. Interesting results were also obtained with a second immunotherapy-based combination consisting of pembrolizumab (anti- programmed death-ligand 1) and lenvatinib. In an open-label phase Ib trial, 104 patients with advanced HCC (BCLC stage B or C, Child-Pugh A, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 0-1) were treated with lenvatinib (12 mg/d in patients weighing ≥ 60 kg; 8 mg/d in < 60 kg) in combination with pembrolizumab (200 mg intravenously every 3 wk). Among the 100 eligible patients, an impressive ORR of 46% was obtained, which is markedly higher than 24% and 17% ORR obtained with lenvatinib or pembrolizumab monotherapy in the REFLECT and Keynote-224 trials, respectively[11,38,39]. The responses to the lenvatinib-pembrolizumab combination also proved to be durable, with a median response duration of 8.6 mo. The median OS reported with this combination was unprecedented at 22 mo, while patients had a median PFS of 9.3 mo[36]. Based on these findings, the United States Food and Drug Administration granted a breakthrough designation for the use of this combination in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced HCC. However, after the publication of the IMbrave 150 results, this breakthrough designation was put on hold (at that point, pembrolizumab-lenvatinib no longer showed evidence of meaningful improvement over available therapies and, as a result, no longer met the criteria for accelerated approval). Currently, the lenvatinib-pembrolizumab combination is being compared to lenvatinib alone in the randomized phase III LEAP-002 trial, which includes 750 unresectable HCC patients who have not received previous treatment for HCC (NCT03713593). The results of this study are eagerly awaited.

Since 2008, sorafenib has been the undisputed standard of care for patients with unresectable HCC who have not received previous treatment for their advanced disease. It took until 2018 for an alternative drug to emerge. In fact, the publication of the pivotal REFLECT trial demonstrated that lenvatinib is non-inferior to sorafenib in terms of OS in the first-line treatment of patients with unresectable HCC. In addition, lenvatinib was shown to be associated with a higher ORR and significantly longer PFS than sorafenib. This leaves patients and clinicians with two equally effective first-line treatment options for patients with unresectable HCC. For physicians to choose which TKI is best to use, they need to consider the individual patient and disease characteristics and consider the specific toxicity profile of both agents. The recent publication of the IMbrave 150 trial demonstrating the superiority of atezolizumab-bevacizumab combination over sorafenib in this setting will radically change the way we treat this disease type. Additionally, the results with the pembrolizumab-lenvatinib combi

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aoki H, Lee BS, Niu ZS S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | GLOBOCAN. GLOBOCAN cancer Fact Sheet Liver cancer. [Cited 15 February 2021]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/11-Liver-fact-sheet.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391:1301-1314. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2800] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3379] [Article Influence: 563.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration, Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, Allen C, Al-Raddadi R, Alvis-Guzman N, Amoako Y, Artaman A, Ayele TA, Barac A, Bensenor I, Berhane A, Bhutta Z, Castillo-Rivas J, Chitheer A, Choi JY, Cowie B, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dey S, Dicker D, Phuc H, Ekwueme DU, Zaki MS, Fischer F, Fürst T, Hancock J, Hay SI, Hotez P, Jee SH, Kasaeian A, Khader Y, Khang YH, Kumar A, Kutz M, Larson H, Lopez A, Lunevicius R, Malekzadeh R, McAlinden C, Meier T, Mendoza W, Mokdad A, Moradi-Lakeh M, Nagel G, Nguyen Q, Nguyen G, Ogbo F, Patton G, Pereira DM, Pourmalek F, Qorbani M, Radfar A, Roshandel G, Salomon JA, Sanabria J, Sartorius B, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Sepanlou S, Shackelford K, Shore H, Sun J, Mengistu DT, Topór-Mądry R, Tran B, Ukwaja KN, Vlassov V, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wakayo T, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Yonemoto N, Younis M, Yu C, Zaidi Z, Zhu L, Murray CJL, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies From 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and National Level: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1683-1691. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 924] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1245] [Article Influence: 249.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Golabi P, Rhea L, Henry L, Younossi ZM. Hepatocellular carcinoma and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Int. 2019;13:688-694. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182-236. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3934] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4903] [Article Influence: 817.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Giannini EG, Farinati F, Ciccarese F, Pecorelli A, Rapaccini GL, Di Marco M, Benvegnù L, Caturelli E, Zoli M, Borzio F, Chiaramonte M, Trevisani F; Italian Liver Cancer (ITA. LI.CA) group. Prognosis of untreated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;61:184-190. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 169] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz JF, Borbath I, Häussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J; SHARP Investigators Study Group. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9016] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9507] [Article Influence: 594.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, Pracht M, Yokosuka O, Rosmorduc O, Breder V, Gerolami R, Masi G, Ross PJ, Song T, Bronowicki JP, Ollivier-Hourmand I, Kudo M, Cheng AL, Llovet JM, Finn RS, LeBerre MA, Baumhauer A, Meinhardt G, Han G; RESORCE Investigators. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56-66. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2160] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2366] [Article Influence: 338.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY, Cicin I, Merle P, Chen Y, Park JW, Blanc JF, Bolondi L, Klümpen HJ, Chan SL, Zagonel V, Pressiani T, Ryu MH, Venook AP, Hessel C, Borgman-Hagey AE, Schwab G, Kelley RK. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:54-63. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1268] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1471] [Article Influence: 245.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, Assenat E, Brandi G, Pracht M, Lim HY, Rau KM, Motomura K, Ohno I, Merle P, Daniele B, Shin DB, Gerken G, Borg C, Hiriart JB, Okusaka T, Morimoto M, Hsu Y, Abada PB, Kudo M; REACH-2 study investigators. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:282-296. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1027] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1052] [Article Influence: 210.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, Baron A, Park JW, Han G, Jassem J, Blanc JF, Vogel A, Komov D, Evans TRJ, Lopez C, Dutcus C, Guo M, Saito K, Kraljevic S, Tamai T, Ren M, Cheng AL. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163-1173. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3128] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3029] [Article Influence: 504.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, Cheng AL, Mathurin P, Edeline J, Kudo M, Han KH, Harding JJ, Merle P, Rosmorduc O, Wyrwicz L, Schott E, Choo SP, Kelley RK, Begic D, Chen G, Neely J, Anderson J, Sangro B. CheckMate 459: A randomized, multi-center phase III study of nivolumab (NIVO) vs sorafenib (SOR) as first-line (1L) treatment in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC). Annals Oncol. 2019;30:v874-v8745. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 433] [Article Influence: 86.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Finn R, Ryoo B-Y, Merle P, Kudo M, Bouattour M, Lim H-Y, Breder VV, Edeline J, Chao Y, Ogasawara S, Yau T, Garrido M, Chan SL, Knox JJ, Daniele B, Ebbinghaus S, Chen E, Siegel AB, Zhu AX, Cheng AL, and for the KEYNOTE-240 Investigators. Results of KEYNOTE-240: phase 3 study of pembrolizumab (Pembro) vs best supportive care (BSC) for second line therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:15_suppl, 4004-4004. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 129] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Xu DZ, Hernandez S, Liu J, Huang C, Mulla S, Wang Y, Lim HY, Zhu AX, Cheng AL; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894-1905. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2542] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3333] [Article Influence: 833.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Cervello M, Bachvarov D, Lampiasi N, Cusimano A, Azzolina A, McCubrey JA, Montalto G. Molecular mechanisms of sorafenib action in liver cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2843-2855. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 110] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS, Xu J, Sun Y, Liang H, Liu J, Wang J, Tak WY, Pan H, Burock K, Zou J, Voliotis D, Guan Z. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25-34. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3854] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4336] [Article Influence: 271.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Iavarone M, Cabibbo G, Piscaglia F, Zavaglia C, Grieco A, Villa E, Cammà C, Colombo M; SOFIA (SOraFenib Italian Assessment) study group. Field-practice study of sorafenib therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective multicenter study in Italy. Hepatology. 2011;54:2055-2063. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 291] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ganten TM, Stauber RE, Schott E, Malfertheiner P, Buder R, Galle PR, Göhler T, Walther M, Koschny R, Gerken G. Sorafenib in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Results of the Observational INSIGHT Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:5720-5728. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Reiss KA, Yu S, Mamtani R, Mehta R, D'Addeo K, Wileyto EP, Taddei TH, Kaplan DE. Starting Dose of Sorafenib for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Retrospective, Multi-Institutional Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3575-3581. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hollebecque A, Cattan S, Romano O, Sergent G, Mourad A, Louvet A, Dharancy S, Boleslawski E, Truant S, Pruvot FR, Hebbar M, Ernst O, Mathurin P. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma: the impact of the Child-Pugh score. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1193-1201. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Marrero JA, Kudo M, Venook AP, Ye SL, Bronowicki JP, Chen XP, Dagher L, Furuse J, Geschwind JH, de Guevara LL, Papandreou C, Takayama T, Sanyal AJ, Yoon SK, Nakajima K, Lehr R, Heldner S, Lencioni R. Observational registry of sorafenib use in clinical practice across Child-Pugh subgroups: The GIDEON study. J Hepatol. 2016;65:1140-1147. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 258] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Leal CRG, Magalhães C, Barbosa D, Aquino D, Carvalho B, Balbi E, Pacheco L, Perez R, de Tarso Pinto P, Setubal S. Survival and tolerance to sorafenib in Child-Pugh B patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Invest New Drugs. 2018;36:911-918. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cheng AL, Kang YK, Lin DY, Park JW, Kudo M, Qin S, Chung HC, Song X, Xu J, Poggi G, Omata M, Pitman Lowenthal S, Lanzalone S, Yang L, Lechuga MJ, Raymond E. Sunitinib versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular cancer: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4067-4075. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 564] [Article Influence: 51.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhu AX, Rosmorduc O, Evans TR, Ross PJ, Santoro A, Carrilho FJ, Bruix J, Qin S, Thuluvath PJ, Llovet JM, Leberre MA, Jensen M, Meinhardt G, Kang YK. SEARCH: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sorafenib plus erlotinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:559-566. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 397] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tohyama O, Matsui J, Kodama K, Hata-Sugi N, Kimura T, Okamoto K, Minoshima Y, Iwata M, Funahashi Y. Antitumor activity of lenvatinib (e7080): an angiogenesis inhibitor that targets multiple receptor tyrosine kinases in preclinical human thyroid cancer models. J Thyroid Res. 2014;2014:638747. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 305] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ikeda K, Kudo M, Kawazoe S, Osaki Y, Ikeda M, Okusaka T, Tamai T, Suzuki T, Hisai T, Hayato S, Okita K, Kumada H. Phase 2 study of lenvatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:512-519. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 235] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Kariyama K, Takaguchi K, Atsukawa M, Itobayashi E, Tsuji K, Tajiri K, Hirooka M, Shimada N, Shibata H, Ishikawa T, Ochi H, Tada T, Toyoda H, Nouso K, Tsutsui A, Itokawa N, Imai M, Joko K, Hiasa Y, Michitaka K; Real-life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group, HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics in Japan). Clinical features of lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in real-world conditions: Multicenter analysis. Cancer Med. 2019;8:137-146. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 95] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sho T, Suda G, Ogawa K, Kimura M, Shimazaki T, Maehara O, Shigesawa T, Suzuki K, Nakamura A, Ohara M, Umemura M, Kawagishi N, Natsuizaka M, Nakai M, Morikawa K, Furuya K, Baba M, Yamamoto Y, Kobayashi T, Meguro T, Saga A, Miyagishima T, Yokoo H, Kamiyama T, Taketomi A, Sakamoto N. Early response and safety of lenvatinib for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in a real-world setting. JGH Open. 2020;4:54-60. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tomonari T, Sato Y, Tanaka H, Tanaka T, Fujino Y, Mitsui Y, Hirao A, Taniguchi T, Okamoto K, Sogabe M, Miyamoto H, Muguruma N, Kagiwada H, Kitazawa M, Fukui K, Horimoto K, Takayama T. Potential use of lenvatinib for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma including after treatment with sorafenib: Real-world evidence and in vitro assessment via protein phosphorylation array. Oncotarget. 2020;11:2531-2542. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ohki T, Sato K, Kondo M, Goto E, Sato T, Kondo Y, Akamatsu M, Sato S, Yoshida H, Koike Y, Obi S. Impact of Adverse Events on the Progression-Free Survival of Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Lenvatinib: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2020;7:141-149. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Atsukawa M, Hirooka M, Tsuji K, Ishikawa T, Takaguchi K, Kariyama K, Itobayashi E, Tajiri K, Shimada N, Shibata H, Ochi H, Tada T, Toyoda H, Nouso K, Tsutsui A, Nagano T, Itokawa N, Hayama K, Imai M, Joko K, Koizumi Y, Hiasa Y, Michitaka K, Kudo M; Real-life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group, HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics in Japan). Prognostic factor of lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in real-world conditions-Multicenter analysis. Cancer Med. 2019;8:3719-3728. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kudo M. Lenvatinib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2017;6:253-263. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kobayashi M, Kudo M, Izumi N, Kaneko S, Azuma M, Copher R, Meier G, Pan J, Ishii M, Ikeda S. Cost-effectiveness analysis of lenvatinib treatment for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) compared with sorafenib in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:558-570. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kim JJ, McFarlane T, Tully S, Wong WWL. Lenvatinib Versus Sorafenib as First-Line Treatment of Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Cost-Utility Analysis. Oncologist. 2019;. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Han KH. Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma With Lenvatinib. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2018;14:662-664. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Kuzuya T, Ishigami M, Ito T, Ishizu Y, Honda T, Ishikawa T, Fujishiro M. Initial Experience of Ramucirumab Treatment After Lenvatinib Failure for Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:2089-2093. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Tada T, Ogawa C, Tani J, Fukunishi S, Atsukawa M, Hirooka M, Tsuji K, Ishikawa T, Takaguchi K, Kariyama K, Itobayashi E, Tajiri K, Shimada N, Shibata H, Ochi H, Kawata K, Toyoda H, Ohama H, Nouso K, Tsutsui A, Nagano T, Itokawa N, Hayama K, Arai T, Imai M, Koizumi Y, Nakamura S, Michitaka K, Hiasa Y, Kudo M; Real-life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group and HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular-carcinoma experts from 48 clinics in Japan). Therapeutic efficacy of ramucirumab after lenvatinib for post-progression treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2021;9:133-138. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Narayan V, Kahlmeyer A, Dahm P, Skoetz N, Risk MC, Bongiorno C, Patel N, Hwang EC, Jung JH, Gartlehner G, Kunath F. Pembrolizumab monotherapy versus chemotherapy for treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma with disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy. A Cochrane Rapid Review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7:CD012838. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, Cattan S, Ogasawara S, Palmer D, Verslype C, Zagonel V, Fartoux L, Vogel A, Sarker D, Verset G, Chan SL, Knox J, Daniele B, Webber AL, Ebbinghaus SW, Ma J, Siegel AB, Cheng AL, Kudo M; KEYNOTE-224 investigators. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:940-952. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1184] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1590] [Article Influence: 265.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |