Published online Oct 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i10.670

Peer-review started: April 5, 2016

First decision: July 13, 2016

Revised: July 27, 2016

Accepted: August 17, 2016

Article in press: August 18, 2016

Published online: October 27, 2016

Over the last two decades, advances in laparoscopic surgery and minimally invasive techniques have transformed the operative management of neonatal colorectal surgery for conditions such as anorectal malformations (ARMs) and Hirschsprung’s disease. Evolution of surgical care has mainly occurred due to the use of laparoscopy, as opposed to a laparotomy, for intra-abdominal procedures and the development of trans-anal techniques. This review describes these advances and outlines the main minimally invasive techniques currently used for management of ARMs and Hirschsprung’s disease. There does still remain significant variation in the procedures used and this review aims to report the current literature comparing techniques with an emphasis on the short- and long-term clinical outcomes.

Core tip: This review describes the recent evolution of neonatal colorectal surgery. It details the advances and current techniques since the introduction of laparoscopic surgery and minimally invasive approaches to the surgical management of anorectal malformations and Hirschsprung’s disease. This review focuses on the various surgical options available and the benefits of these different techniques, outlining the current literature reporting the short- and long-term outcomes for these procedures.

- Citation: Bandi AS, Bradshaw CJ, Giuliani S. Advances in minimally invasive neonatal colorectal surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(10): 670-678

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i10/670.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i10.670

The application of minimal access techniques within paediatric surgery has evolved considerably in the last thirty years since the advent of laparoscopic surgery in the late 1980s. Advances in laparoscopic techniques and the development of new entirely transanal procedures has transformed the operative management of paediatric colorectal conditions, in particular Hirschsprung’s disease and anorectal malformations (ARMs). Improving technology and refinement of techniques over the last decade has allowed these minimally invasive approaches to be used in increasingly challenging cases.

The posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP), a perineal approach to the correction of ARMs, has been standard practice since it was first described by Peña in the 1980s[1]. Laparoscopy in the operative management of ARMs was first described in 1998. The laparoscopic-assisted anorectal pull-through (LAARP) was popularised in 2000[2]. Proponents advocated this approach to avoid a laparotomy to ligate a high fistula and aimed to reduce post-operative pain and recovery time.

The LAARP is beneficial for recto-bladder neck fistulae and it may facilitate clear identification of the levator muscles so the surgeon can be sure of the correct position of the anus, avoiding the risks of sagittal dissection[3]. It was hoped this small perineal wound, opening only in the centre of the muscle complex, would improve functional outcomes by its relative preservation of the sphincter muscles[4].

Indications and use of laparoscopy initially expanded rapidly due to the benefit of avoiding extensive perineal dissection which was postulated to reduce soft tissue rectal scarring and lead to improved rectal compliance. However, the management of low anorectal malformation in males (recto-perineal and retro-bulbar fistulae) via a laparoscopic approach has resulted in an increased risk of urethral injury due to a difficult and extensive pelvic dissection as well as injury to the rectal nerves and pelvic plexus. This results in poor bowel function and therefore laparoscopy in these cases is unwarranted[5,6].

ARMs with a recto-urethral fistula have been traditionally managed with colostomy formation in the newborn period, followed by definitive anorectoplasty at a later stage. Good positioning of the colostomy is vital to avoid problems in mobilizing the rectum[3]. There is an argument in favour of the use of laparoscopy for stoma formation to ensure that it is appropriately sited and also to allow for fistula assessment and consideration of primary repair[7]. Laparoscopy has therefore allowed surgeons to treat patients with recto-bladder neck fistula ARMs with a single procedure without an initial colostomy. Small case series have shown that this is feasible and without the presumed difficulties of abdominal distension when the patient is operated within 48 h after birth[7]. Though the rectum may be dilated with meconium, it has been shown to be feasible with laparoscopic manipulation to perform the dissection safely. Initial concerns about handling of friable bowel leading to injuries have not been seen in the published series reporting this technique[7].

We prefer a three stage operation in case of high ARMs with or without fistula. Following stoma formation, a colostogram is performed to identify the presence and level of fistula[4]. Laparoscopic assisted pull-through is usually performed at 3 mo of age[4].

In recto-bladder neck fistula, the fistula is located approximately 2 cm below the peritoneal reflection, and the rectum communicates with the urinary tract in a T fashion, which means that there is a minimal common wall between the distal part of the rectum and the urinary tract. The laparoscopic approach provides an excellent view of the peritoneal reflection, the ureters and the vas deferens, which must be visualised to prevent injury when dividing a recto-bladder neck fistula[2].

The operation is begun by dividing the peritoneum around the distal rectum to create a plane of dissection to be followed distally. The dissection should occur on the rectal wall. The rectum rapidly narrows as it reaches its communication with the bladder neck. Dividing the fistula as close to the urinary tract as possible is required to prevent the formation of a diverticulum in the future[8]. This can be confirmed by noting that the rectum has narrowed sufficiently to allow the 3 mm Maryland laparoscopic instrument to completely clamp across the fistula. A suture with 3/0 PDS is used to ligate the fistula. A submucosal dissection plane to create a mucosal tube of the distal rectum has been advocated as this facilitates easier ligation, further limiting the amount of fistula tissue left attached to the urethra[9]. Initial reports described clip or endoloop ligation of the fistula but later studies have shown that simple sharp ligation flush with the bladder is the best technique[10,11].

The distal rectum is then mobilized by dividing feeding vessels until there is enough length to pull the rectum comfortably down to the perineum. If the colostomy was created too distal in the sigmoid it may prevent this mobilisation.

The pubococcygeus muscle is then identified by inspection of the pelvic floor. A hiatus is located along the anterior surface of the two muscle bellies just posterior to the urethra which is the anatomical landmark where the rectum will be delivered from the pelvic side of the dissection[2,5].

Various techniques have been described for creation of the pull-through channel at the optimal site. The laparoscopic Peña electrostimulator has been used to identify accurately the centre of the muscle complex in the perineum[10,12]. This can be particularly useful in cases of immature and unclear levator muscles[3,13]. The positioning of the channel can be further guided with perineal and endoscopic ultrasound which can also serve as a useful tool for ensuring that the dissection is not risking injury to genitourinary structures[14,15].

Entry into the pelvis from below can be facilitated under laparoscopic vision with a Verees needle and serial dilatation until a 10-12 mm trocar can be placed to allow the bowel to be pulled through and the anoplasty completed[4,9].

Robotic assistance has been used to perform these operations in a limited series. The increased range of movement added with 3D vision technology aims to make the pelvic dissection easier for the surgeon. Currently this is hampered by the size of these infants but, as these technology advances, robotic assistance may prove a valuable tool in minimally invasive pull-through surgery for ARMs[16].

As with other laparoscopic procedures, surgeons aiming for improved cosmesis have reported successful completion of LAARP using single-port techniques but such techniques are not commonplace due to the technical challenges and cosmetic benefits[17].

Anal stenosis is a significant complication following PSARP and remains so in case series of LAARP. Ischaemia of the pull-through and tension on the anastomosis are causes of stenosis but it can also result from non-compliance with the postoperative dilatation regimes[10].

Initial pitfalls encountered with the laparoscopic approach have been bladder/urethral injuries, bladder/urethral diverticulum and rectal prolapse but as the technique has become more established these problems do not appear to be encountered any more frequently in this group[18].

There is evidence of reduced operating times, post-operative stay and blood loss in the LAARP group compared with open PSARP for high ARMs but again in these case series no clinical outcome difference was found[19,20].

It has been well documented that constipation is a major problem for patients that have undergone corrective surgery for high ARMs[21]. Reviews have indicated a 80%-100% constipation rate following corrective surgery for recto-vesical fistulae[22,23]. Some degree of soiling has been shown to occur in 42%-63% of cases of recto-vesical fistula[23]. It has been noted that the majority of these patients experience resolution of constipation by the time they have progressed through puberty[24]. Long term follow up suggests that approximately half of patients managed with PSARP for high anorectal malformation have an excellent functional result by adulthood[25]. It remains to be seen whether LAARP will improve this figure.

Outcome data for patients that have had LAARP remains limited to small series with relatively short follow up. The incidence of the most commonly described outcomes after PSARP and LAARP are shown in Table 1. These rates are calculated from pooled data used in a meta-analyses[26]. An increase in preserved recto-anal relaxation reflex has been shown in patients undergoing LAARP compared to PSARP by performing follow up anorectal manometry[27]. MRI imaging has revealed less peri-rectal fibrosis and sphincter asymmetry in these patients. However, neither of these measures has shown a correlation with a significant clinical improvement in the studies to date[26-29].

| Open PSARP | LAARP | |||||

| High | Low | All | High | Low | All | |

| Short-term outcomes | ||||||

| Mucosal prolapse (%) | 10.7 | 21.2 | 16.4 | 9.8 | 2.9 | 6.2 |

| Long-term outcomes | ||||||

| Defecation dysfunction (%) | 33.3 | 41.8 | 40.3 | 36.4 | 27 | 29.2 |

| Rectoanal inhibitory reflex positive (%) | - | - | 57.4 | - | - | 72.7 |

It has been shown that the objective feedback using a continence evaluation questionnaire is significantly better at 3-4 years post-op in the LAARP group compared to PSARP, however this significance did not persist in patients that had been followed up for 5 years or more[30]. The possible significance of this data remains limited by its small numbers.

Currently the main benefit of the laparoscopic approach is to replace the laparotomy in cases of recto-bladder neck and recto-prostatic urethra fistula. Other potential benefits remain to be confirmed[18,31]. Attempts to review and combine the data of existing studies to ascertain if there are significant benefits have been unsuccessful due to the lack of standardisation of outcome measures reporting between paediatric surgical centres[26,29].

The surgical management of Hirschsprung’s disease has evolved since the basic principles of repair described by Swenson et al[32] in 1948. Progression occurred from a two- or three-stage procedure to a primary operation in the early 1980s[33]. In the single stage primary operation, a laparotomy is used to mobilise the colon followed by an endorectal pull-through. Three main endorectal pull-through techniques are popularly used: Swenson, Soave and Duhamel.

The laparoscopic-assisted primary pull-through was first described by Georgeson et al[34] in 1995. Following this, surgeons quickly began to replace the laparotomy for the transabdominal portion of each of the different pull-through procedures with laparoscopy[35,36]. Subsequently, the entirely transanal endorectal pull-through emerged in 1998[37].

More recent technical advances have also been described in conjunction with the pull-through procedure. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery has been used safely to compliment the transanal endorectal pull-through and the Duhamel’s procedure[38-40]. One series used robotic assistance for the Swenson pull-through in 7 cases. They hypothesize that the increased dexterity as compared to laparoscopic surgery may improve the accuracy of the endorectal dissection and thus improve future outcomes, however this is as yet unproven[41].

The majority of patients with Hirschsprung’s disease are suitable for a definitive primary procedure, using either the laparoscopic-assisted or the primary transanal approach[42]. Both of these techniques can be performed at any age and are routinely performed within the first few months of life[43,44].

Relative contraindications for a primary procedure include severe dilatation of the proximal bowel, significant clinical deterioration due to enterocolitis or long segment Hirschsprung’s disease[42]. These patients may be more appropriately managed with an initial levelling colostomy, which can be achieved with a laparoscopic approach, and a definitive pull-through procedure performed at a later stage. Laparoscopy offers the advantage of visualising the entire bowel, allowing for identification of the transition zone and biopsies prior to creating a stoma at the appropriate level.

Long segment Hirschsprung’s disease is defined as a transition zone proximal to the mid-transverse colon. The most common type is total colonic aganglionosis, which can involve a portion of the terminal ileum. Although any of the three pull-through techniques can be used, the laparoscopic assisted Duhamel’s procedure is favoured in these patients.

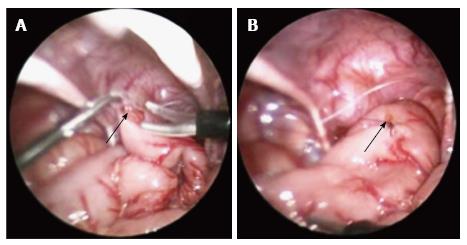

Laparoscopy is first used to take intra-operative frozen section levelling biopsies in order to identify normal ganglionated bowel. The bowel is inspected to identify the transition zone. A seromuscular biopsy is taken from above the transition zone in what appears to be normal bowel. Any perforation or bleeding at this site can be closed with a braided suture (Figure 1). If ganglion cells are absent or there is evidence of thickened nerve fibres then biopsies should be continued proximally until normal ganglionated colon is identified. No dissection of the mesentery or rectum should be started until the level of normal bowel has been confirmed.

At this stage, in those patients found to have a long Hirschsprung’s segment, it may be preferred to create a stoma above the suspected transition zone and delay the definitive procedure to a later stage, in order to await formal histology results.

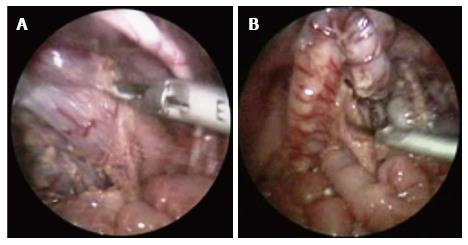

Once the proximal level of the pull-through has been established, mobilisation of the colon with dissection of the mesocolon and mobilisation of the rectum below the peritoneal reflection can be continued laparoscopically (Figure 2). This is usually achieved with hook diathermy or the harmonic scalpel in older children. The trans-anal dissection of the surgeon’s choice then follows. This involves a trans-anal endorectal dissection of the rectum starting 2-3 mm above the dentate line until the rectum and colon is completely free. In a Soave procedure, the first part of the dissection includes only the mucosa and submucosa, leaving a muscular cuff of aganglionated rectum. The posterior wall of this cuff should be incised in order to prevent stenosis. At this stage the pneumoperitoneum can be re-instated, using the laparoscope to visualise the mobilised aganglionic rectum and colon as it is pulled through. This ensures that the bowel has not been kinked or rotated during this process and there is sufficient mobilisation of the colon to prevent tension on the anastomosis. The mesenteric defect or window should then be closed to prevent the risk of an internal hernia. The aganglionated segment is excised and anastomosis of the colon to the rectal mucosa is performed, followed by closure of the laparoscopic port sites[45].

The procedure for the initial levelling biopsies for the laparoscopic Duhamel procedure is the same as for the laparoscopic-assisted endorectal pull-through, as described above.

After the level of normal ganglionated bowel has been identified, the colon needs to be mobilised adequately and the mesentery of the distal aganglionated bowel can be divided. Once dissection has reached the peritoneal reflection, the rectum is closed to create the rectal pouch, either by oversewing the bowel or using an automatic stapler. Following this, the posterior rectum is then incised transanally, approximately 1 cm proximal to the dentate line. This creates an opening for the pull-through. A tunnel behind the rectum is created with a smooth dissector and dilated up to an adequate size with Hegar dilators. The proximal colon is pulled through the tunnel using a traction suture under laparoscopic vision. The colon is then anastomosed to the posterior wall of the rectum at the incision site. This can be completed with an automatic stapler to remove the wall between the rectal stump and the colon. Correct positioning of the pulled-through colon, without twisting or tension, is then confirmed using the laparoscopic view prior to closure[46,47].

The totally trans-anal endorectal pull-through was derived from the laparoscopic-assisted endorectal pull-through. It excludes the initial biopsies and proceeds directly to the trans-anal endorectal dissection, assuming that if the infant is responding to rectal wash-outs there is a classic Hirschsprung’s disease, with the transition zone at the recto-sigmoid colon. Either a lonestar retractor or retracting sutures are placed between the perianal skin and the dentate line. The rectal mucosa dissection begins 2-3 mm above the dentate line. In a Soave procedure, the dissection then proceeds submucosally until the peritoneal reflection at the level of the pouch of Douglas is reached. At this point the bowel can be dissected full-thickness after separating the sero-muscular plane 360 degrees. The muscular cuff should be vertically split posteriorly to avoid stenosis. The dissection continues along the rectal wall until a clear difference in calibre is noted, representing the transition zone. Alternatively in the Swenson procedure, the dissection of the rectum is full thickness from the beginning, leaving no muscular cuff. Once the peritoneal reflection has been reached the colon will be pulled through and the mesentery is divided trans-anally. Care must be taken to avoid rotating the bowel as the dissection progresses. Biopsies can be taken and sent as frozen section during the procedure to confirm the level of the transition zone. Once normal bowel has been reached the aganglionic segment can be excised and the anastomosis performed[37,44].

The trans-anal pull-through has gained popularity due to its simplicity. It avoids the intra-peritoneal dissection and the need for laparoscopic expertise and equipment, which may be particularly important in low-income countries. However, in cases where the transition is proximal to the sigmoid colon mobilisation of the descending colon is usually required in order to perform an anastomosis without tension. This can be achieved laparoscopically if necessary.

The main benefit of using the laparoscopic-assisted approach over the primary trans-anal approach is early identification of the transition zone prior to dissection of the mesentery so that long segment Hirschsprung’s can be identified and dealt with appropriately. Laparoscopy also allows full mobilisation of the colon on a mesocolic pedicle to minimise tension on the anastomosis, and reduces the risk of rotational abnormalities during the pull-through[48]. Additionally, it reduces the need for a lengthy trans-anal dissection resulting in less dilatation of the anal sphincter, a factor that may be associated with faecal incontinence in the long-term[49].

Quoted benefits of laparoscopic surgery over traditional open techniques include reduced post-operative pain, quicker recovery of bowel function, shorter length of stay and improved cosmesis[43,46,50]. On the contrary, the disadvantage is thought to be a longer operative time[46,50]. Reported operative time for the open approach ranges from 91.3-297 min, laparoscopic approach from 150-257 min, and trans-anal approach from 43.5-258 min. Meta-analyses directly comparing these techniques demonstrated a shorter operating time in laparoscopic procedures and trans-anal procedures[51,52]. Reported length of stay for open procedures range from 6.9 to 18.7 d, laparoscopic-assisted procedures from 3.6 to 10.4 d and trans-anal endorectal procedures from 2.6 to 9.8 d. Two studies comparing laparoscopic vs open procedures showed a significantly shorter average length of stay with laparoscopic procedures; 4 d following the laparoscopic endorectal pull-through, 7 d with the laparoscopic Duhamel pull-through and 10 d after an open Duhamel pull-through[46,53]. When compared to the transabdominal approach, both the laparoscopic-assisted pull-through and the trans-anal endorectal pull-through have been shown to have a shorter length of stay[51,52].

Conversion of a laparoscopic to an open procedure usually occurs for technical reasons and conversion rates range between 1%-2.5%[39,43,54].

Recognised early post-operative complications of the pull-through procedure for Hirschsprung’s disease include bleeding, anastomotic leak, perforation, adhesive bowel obstruction and post-operative enterocolitis. Late complications include anastomotic stenosis, enterocolitis, need for re-do surgery. These have all been described in association with the minimally-invasive techniques[39,43,54-56]. Rates of these post-operative complications are comparable in laparoscopic and open approaches and may favour laparoscopic procedures. Although no individual comparative study has shown any significant difference in complication rates, pooled data from a meta-analysis demonstrated fewer complications in the laparoscopic operations[51]. A meta-analysis comparing laparoscopic vs open Duhamel procedure showed lower rates of further surgery in the laparoscopic group, with 14% compared to 25% of patients after the open procedure. The incidence of post-operative enterocolitis is 10% after the laparoscopic Duhamel’s procedure and 15% after the open procedure, however this did not reach significance[57].

A large cohort study investigating the transanal endorectal pull-through suggested lower rates of early complications compared to the transabdominal approach[58]. The reported incidence of enterocolitis following the transanal endorectal pull-through ranges from 4.6%-54%, with a systematic review suggesting an incidence of 10.2%[59]. Comparison with both the transabdominal approach and laparoscopic-assisted approaches have not demonstrated any difference in the rates of post-operative enterocolitis[52,60].

Functional outcomes after surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease relate to impaired bowel function. Both severe constipation and faecal incontinence are experienced by these patients even into adulthood, although bowel function has been demonstrated to improve with increasing age[61]. The rate of severe constipation does decrease by young adulthood[62]. Additionally, faecal incontinence, impacting on quality of life, was reported less frequently with longer follow-up. It seems that puberty is the critical age for this improvement as bowel function in late adolescence and adulthood remains similar[63].

Investigation of the long-term outcomes of Hirschsprung’s disease managed with minimally invasive techniques has been carried out, with on average up to 5 years of follow-up. There have been 3 meta-analyses undertaken comparing different techniques; laparoscopic to open Duhamel procedure, trans-anal endorectal approach to transabdominal approach, and trans-anal endorectal approach to laparoscopic endoanal approach[52,57,60]. Unfortunately, the data has a significant degree of heterogeneity, both in terms of the actual surgical techniques used and in how the outcomes, constipation and faecal incontinence, were defined. The incidence of the most commonly described outcomes across the different techniques is demonstrated in Table 2. These rates are calculated from pooled data used in the meta-analyses.

| Open pull-through | Laparoscopic-assisted pull-through | Transanal endorectal pull-through | |||

| Swenson/soave | Duhamel | Endoanal | Duhamel | ||

| Short-term outcomes | |||||

| Length of stay (d) | 12.5 | 9.8 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 5.1 |

| Enterocolitis (%) | 26 | 15 | 28 | 10 | 25 |

| Long-term outcomes | |||||

| Constipation (%) | 12 | 23 | 15 | 30 | 11 |

| Faecal incontinence (%) | 26 | 11 | 35 | 4 | 20 |

Meta-analysis comparing the laparoscopic Duhamel to the open Duhamel procedure indicated that the incidence of faecal incontinence seems to be significantly lower with the laparoscopic approach (4% and 11% respectively; P = 0.02), while the incidence of severe constipation does not seem differ (30% and 23% respectively; P = 0.12)[57]. Another study suggested lower constipation rates and better continence at 1-year follow-up for the laparoscopic-assisted endoanal pull-through over the Duhamel procedure[53].

Initial early evidence with the transanal endorectal pull-through raised concerns about higher rates of faecal incontinence[49]. This was hypothesized to be related to overstretching of the anal sphincter muscles during the neonatal procedure. Recently comparison of the transanal endorectal approach to the trans-abdominal approach suggested reduced rates of incontinence and constipation[52]. While a comparison between the transanal endorectal approach to the laparoscopic-assisted endoanal approach demonstrated no difference in outcome[60].

Currently it remains too early to fully evaluate the longer term outcomes into adulthood of minimally invasive techniques vs the traditional open procedures[63].

Over the past two decades, there has been significant evolution in the surgical management of neonatal colorectal conditions. Advances in the technology and understanding of minimally invasive surgery have allowed these techniques to be adapted for use in small infants for correction of ARMs and Hirschsprung’s disease. Laparoscopy and minimally invasive techniques are now safely and routinely used in the management of these major congenital anomalies. As experience grows, these techniques will be used for increasingly complex and challenging cases.

Benefits of minimally invasive surgery have been demonstrated, in terms of shorter hospital stay and improved cosmesis, and other potential benefits are hypothesized. Major improvements in functional outcomes remain as yet unproven. Significant variation does still exist in the specific operative techniques. High quality data investigating different techniques and comparing both short-term and long-term outcomes is still needed to determine which procedures are most effective for our patients.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Pochhammer J S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | deVries PA, Peña A. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty. J Pediatr Surg. 1982;17:638-643. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Georgeson KE, Inge TH, Albanese CT. Laparoscopically assisted anorectal pull-through for high imperforate anus--a new technique. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:927-930; discussion 930-931. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 218] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lima M, Tursini S, Ruggeri G, Aquino A, Gargano T, De Biagi L, Ahmed A, Gentili A. Laparoscopically assisted anorectal pull-through for high imperforate anus: three years’ experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006;16:63-66. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Georgeson K. Laparoscopic-assisted anorectal pull-through. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16:266-269. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rangel SJ, de Blaauw I. Advances in pediatric colorectal surgical techniques. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010;19:86-95. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Iwai N, Fumino S. Surgical treatment of anorectal malformations. Surg Today. 2013;43:955-962. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vick LR, Gosche JR, Boulanger SC, Islam S. Primary laparoscopic repair of high imperforate anus in neonatal males. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1877-1881. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Uchida H, Iwanaka T, Kitano Y, Kudou S, Ishimaru T, Yotsumoto K, Gotoh C, Yoshida M. Residual fistula after laparoscopically assisted anorectoplasty: is it a rare problem? J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:278-281. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Srimurthy KR, Ramesh S, Shankar G, Narenda BM. Technical modifications of laparoscopically assisted anorectal pull-through for anorectal malformations. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:340-343. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | England RJ, Warren SL, Bezuidenhout L, Numanoglu A, Millar AJ. Laparoscopic repair of anorectal malformations at the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital: taking stock. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:565-570. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rollins MD, Downey EC, Meyers RL, Scaife ER. Division of the fistula in laparoscopic-assisted repair of anorectal malformations-are clips or ties necessary? J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:298-301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yamataka A, Segawa O, Yoshida R, Kobayashi H, Kameoka S, Miyano T. Laparoscopic muscle electrostimulation during laparoscopy-assisted anorectal pull-through for high imperforate anus. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1659-1661. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iwanaka T, Arai M, Kawashima H, Kudou S, Fujishiro J, Matsui A, Imaizumi S. Findings of pelvic musculature and efficacy of laparoscopic muscle stimulator in laparoscopy-assisted anorectal pull-through for high imperforate anus. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:278-281. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Saeki M, Nakano M, Kuroda T. Sacroperineal anorectoplasty using intraoperative ultrasonography: evaluation by computed tomography. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1484-1486. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yamataka A, Yoshida R, Kobayashi H, Lane GJ, Kurosaki Y, Segawa O, Kameoka S, Miyano T. Intraoperative endosonography enhances laparoscopy-assisted colon pull-through for high imperforate anus. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1657-1660. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Albassam A, Gado A, Mallick MS, Alnaami M, Al-Shenawy W. Robotic-assisted anorectal pull-through for anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1794-1797. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Diao M, Li L, Ye M, Cheng W. Single-incision laparoscopic-assisted anorectoplasty using conventional instruments for children with anorectal malformations and rectourethral or rectovesical fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1689-1694. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bischoff A, Peña A, Levitt MA. Laparoscopic-assisted PSARP - the advantages of combining both techniques for the treatment of anorectal malformations with recto-bladderneck or high prostatic fistulas. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:367-371. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ming AX, Li L, Diao M, Wang HB, Liu Y, Ye M, Cheng W. Long term outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted anorectoplasty: a comparison study with posterior sagittal anorectoplasty. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:560-563. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kimura O, Iwai N, Sasaki Y, Tsuda T, Deguchi E, Ono S, Furukawa T. Laparoscopic versus open abdominoperineal rectoplasty for infants with high-type anorectal malformation. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:2390-2393. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rintala R, Lindahl H, Marttinen E, Sariola H. Constipation is a major functional complication after internal sphincter-saving posterior sagittal anorectoplasty for high and intermediate anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1054-1058. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nam SH, Kim DY, Kim SC. Can we expect a favorable outcome after surgical treatment for an anorectal malformation? J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:421-424. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | van der Steeg HJ, Botden SM, Sloots CE, van der Steeg AF, Broens PM, van Heurn LW, Travassos DV, van Rooij IA, de Blaauw I. Outcome in anorectal malformation type rectovesical fistula: a nationwide cohort study in The Netherlands. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:1229-1233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rintala RJ, Lindahl HG. Fecal continence in patients having undergone posterior sagittal anorectoplasty procedure for a high anorectal malformation improves at adolescence, as constipation disappears. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1218-1221. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP. Outcome of anorectal malformations and Hirschsprung’s disease beyond childhood. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010;19:160-167. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shawyer AC, Livingston MH, Cook DJ, Braga LH. Laparoscopic versus open repair of recto-bladderneck and recto-prostatic anorectal malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015;31:17-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lin CL, Wong KK, Lan LC, Chen CC, Tam PK. Earlier appearance and higher incidence of the rectoanal relaxation reflex in patients with imperforate anus repaired with laparoscopically assisted anorectoplasty. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1646-1649. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wong KK, Khong PL, Lin SC, Lam WW, Lan LC, Tam PK. Post-operative magnetic resonance evaluation of children after laparoscopic anorectoplasty for imperforate anus. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:33-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Al-Hozaim O, Al-Maary J, AlQahtani A, Zamakhshary M. Laparoscopic-assisted anorectal pull-through for anorectal malformations: a systematic review and the need for standardization of outcome reporting. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1500-1504. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ichijo C, Kaneyama K, Hayashi Y, Koga H, Okazaki T, Lane GJ, Kurosaki Y, Yamataka A. Midterm postoperative clinicoradiologic analysis of surgery for high/intermediate-type imperforate anus: prospective comparative study between laparoscopy-assisted and posterior sagittal anorectoplasty. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:158-162; discussion 162-163. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bischoff A, Martinez-Leo B, Peña A. Laparoscopic approach in the management of anorectal malformations. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015;31:431-437. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Swenson O, Bill AH. Resection of rectum and rectosigmoid with preservation of the sphincter for benign spastic lesions producing megacolon; an experimental study. Surgery. 1948;24:212-220. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | So HB, Schwartz DL, Becker JM, Daum F, Schneider KM. Endorectal “pull-through” without preliminary colostomy in neonates with Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15:470-471. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 122] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Georgeson KE, Fuenfer MM, Hardin WD. Primary laparoscopic pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:1017-1021. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 243] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hoffmann K, Schier F, Waldschmidt J. Laparoscopic Swenson’s procedure in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1996;6:15-17. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | de Lagausie P, Berrebi D, Geib G, Sebag G, Aigrain Y. Laparoscopic Duhamel procedure. Management of 30 cases. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:972-974. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | De la Torre-Mondragón L, Ortega-Salgado JA. Transanal endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:1283-1286. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 217] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Muensterer OJ, Chong A, Hansen EN, Georgeson KE. Single-incision laparoscopic endorectal pull-through (SILEP) for hirschsprung disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1950-1954. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Tang ST, Yang Y, Li SW, Cao GQ, Yang L, Huang X, Shuai L, Wang GB. Single-incision laparoscopic versus conventional laparoscopic endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease: a comparison of short-term surgical results. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:1919-1923. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Xia X, Li N, Wei J, Zhang W, Yu D, Zhu T, Feng J. Single-incision laparoscopic versus conventional laparoscopic surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease: A comparison of medium-term outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:440-443. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hebra A, Smith VA, Lesher AP. Robotic Swenson pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease in infants. Am Surg. 2011;77:937-941. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Somme S, Langer JC. Primary versus staged pull-through for the treatment of Hirschsprung disease. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2004;13:249-255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Georgeson KE, Cohen RD, Hebra A, Jona JZ, Powell DM, Rothenberg SS, Tagge EP. Primary laparoscopic-assisted endorectal colon pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease: a new gold standard. Ann Surg. 1999;229:678-682; discussion 682-683. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | De La Torre L, Langer JC. Transanal endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung disease: technique, controversies, pearls, pitfalls, and an organized approach to the management of postoperative obstructive symptoms. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010;19:96-106. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 100] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Georgeson KE, Robertson DJ. Laparoscopic-assisted approaches for the definitive surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2004;13:256-262. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ghirardo V, Betalli P, Mognato G, Gamba P. Laparotomic versus laparoscopic Duhamel pull-through for Hirschsprung disease in infants and children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:119-123. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Nah SA, de Coppi P, Kiely EM, Curry JI, Drake DP, Cross K, Spitz L, Eaton S, Pierro A. Duhamel pull-through for Hirschsprung disease: a comparison of open and laparoscopic techniques. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:308-312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | van de Ven TJ, Sloots CE, Wijnen MH, Rassouli R, van Rooij I, Wijnen RM, de Blaauw I. Transanal endorectal pull-through for classic segment Hirschsprung’s disease: with or without laparoscopic mobilization of the rectosigmoid? J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:1914-1918. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | El-Sawaf MI, Drongowski RA, Chamberlain JN, Coran AG, Teitelbaum DH. Are the long-term results of the transanal pull-through equal to those of the transabdominal pull-through? A comparison of the 2 approaches for Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:41-47; discussion 47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Travassos DV, Bax NM, Van der Zee DC. Duhamel procedure: a comparative retrospective study between an open and a laparoscopic technique. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2163-2165. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Zhao B, Liu T, Li Q. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of laparoscopic-assisted operations and open operations for Hirschsprung’s disease: evidence from a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:12963-12969. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 52. | Chen Y, Nah SA, Laksmi NK, Ong CC, Chua JH, Jacobsen A, Low Y. Transanal endorectal pull-through versus transabdominal approach for Hirschsprung’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:642-651. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Giuliani S, Betalli P, Narciso A, Grandi F, Midrio P, Mognato G, Gamba P. Outcome comparison among laparoscopic Duhamel, laparotomic Duhamel, and transanal endorectal pull-through: a single-center, 18-year experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:859-863. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Nguyen TL, Bui DH, Tran AQ, Vu TH. Early and late outcomes of primary laparoscopic endorectal colon pull-through leaving a short rectal seromuscular sleeve for Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:2153-2155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Curran TJ, Raffensperger JG. Laparoscopic Swenson pull-through: a comparison with the open procedure. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1155-1156. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Kumar R, Mackay A, Borzi P. Laparoscopic Swenson procedure--an optimal approach for both primary and secondary pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1440-1443. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Scholfield DW, Ram AD. Laparoscopic Duhamel Procedure for Hirschsprung’s Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2016;26:53-61. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Kim AC, Langer JC, Pastor AC, Zhang L, Sloots CE, Hamilton NA, Neal MD, Craig BT, Tkach EK, Hackam DJ. Endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease-a multicenter, long-term comparison of results: transanal vs transabdominal approach. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1213-1220. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Ruttenstock E, Puri P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enterocolitis after one-stage transanal pull-through procedure for Hirschsprung’s disease. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:1101-1105. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Thomson D, Allin B, Long AM, Bradnock T, Walker G, Knight M. Laparoscopic assistance for primary transanal pull-through in Hirschsprung’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006063. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 61. | Conway SJ, Craigie RJ, Cooper LH, Turner K, Turnock RR, Lamont GL, Newton S, Baillie CT, Kenny SE. Early adult outcome of the Duhamel procedure for left-sided Hirschsprung disease--a prospective serial assessment study. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1429-1432. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Diseth TH, Bjørnland K, Nøvik TS, Emblem R. Bowel function, mental health, and psychosocial function in adolescents with Hirschsprung’s disease. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76:100-106. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP. Long-term outcomes of Hirschsprung’s disease. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2012;21:336-343. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 98] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |