Abstract

Until well in the 19th century, the Aristotelian concept of the scala naturae (ladder of nature) was the most common biological theory among Western scientists. It dictated that only humans possessed a rational soul that provided the ability to reason and reflect. Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (1533–1592) was the first philosopher influential enough to lastingly posit that animals are cognitive creatures. His view stirred a fierce controversy, with René Descartes (1596–1650) leading among his many adversaries. Only after it became accepted that animals and humans alike have cognitive abilities, did the research on the influence of conscious awareness and intention on the behavior of an animal become possible in the 20th century. We found the anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1515–1564) to have already rejected the Aristotelian view on the lack of the rational soul in animals in his 1543 opus magnum De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem. His observation “that there is a difference in size according to the amount of reason that they seem to possess: man's brain is the largest, followed by the ape's, the dog's, and so on, corresponding to the amount of rational force that we deduce each animal to have” resonated some 330 years later when Darwin concluded that “the difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind.” We conclude that Vesalius was instrumental in breaking with two millenniums of dominance of the concept of lack of animal cognition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Until well in the 19th century, the Aristotelian concept of the scala naturae (ladder of nature) was the most common biological theory among Western scientists. Aristotle (384–322 BC) had a hierarchical view of life in which all creatures could be grouped in order, with humans being the highest order. Western medieval commentators of Aristotelian theory interpreted this as the scala naturae or the great chain of being, but these were not Aristotle's terms (Allen, 1995 (revised 2015); Tilton, 2009). The scala may be represented by a virtual pyramid that included non-living things (such as minerals and sediment) and the simplest form of life on its lowest levels. Higher levels are occupied by animals with progressively increasing complexity and the top is occupied by humans, with only the angels and God above them. Of the earthly creatures, only humans were felt to possess a rational soul that provided the ability to reason and reflect. Animals were believed to be able to react to sensation by use of a sensitive soul (Sobol, 1993). Because this view agreed with the Christian belief that humans occupied an exceptional and superior position in God’s creation, the Aristotelian theory became dominant.

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (1533–1592) was the first philosopher who was influential enough to lastingly posit that animals are cognitive creatures (Charalampous, 2016). This view stirred a fierce controversy, with René Descartes (1596–1650) leading among his many adversaries (Charalampous, 2016; Richards, 1987). Like the Aristotelians, Descartes denied that animals had reason or intelligence. Unlike the Aristotelians, however, Descartes felt that animal reaction to sensations or perceptions could be explained purely mechanistically, rather than being initiated by an Aristotelian sensitive soul (Allen, 1995 (revised 2015)). After de Montaigne and Descartes, naturalists disputed violently until well in the 18th century over the controversial interpretation of animal behavior (Charalampous, 2016), debating on whether the activities of animal “brutes” were to be regarded as congenitally fixed or as the consequences of reasoned choice (Richards, 1987).

Meanwhile, the increasing acceptance of animals as intelligent beings had tantalizing implications for human cognitive psychology (Charalampous, 2016). Evolutionary theories of mind and behavior appeared distinctly for the first time in the 19th century and accumulated in the famous works The Descent of Man (1871) and The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) by Charles Darwin (1809–1882) (Darwin & Wilson, 2010). Darwin concluded that “the difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind” (p. 837) (Darwin & Wilson, 2010). Only after it became accepted that animals and humans alike have cognitive abilities, did the research on the influence of conscious awareness and intention on the behavior of an animal (cognitive ethology) become possible in the 20th century (Bekoff, Allen, & Burghardt, 2002).

We found the anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1515–1564) to have rejected the Aristotelian view on the lack of the rational soul in animals, some 40 years before de Montaigne posited his views and some 90 years before Descartes formulated his objections to both the Aristotelian view on the animal sensitive soul and de Montaigne’s view on animal cognition. To understand the extent and moment of Vesalius’ rejection, we present the texts that Vesalius spent on it in his 1543 opus magnum De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (De Fabrica) (Vesalius, 1543), and put his observations in historical perspective. As a result of the inaccessibility of Vesalius’ written Latin (Lydiatt & Bucher, 2012; D. J. Lanska, 2014), it has not been recognized to date that Vesalius has been instrumental in breaking with the concept of lack of animal cognition. The English translation of De Fabrica presented recently by Australian classicist W.F. Richardson and anatomist J.B. Carman enabled us to do so (Richardson & Carman, 2009).

Aristotelian view on animal cognition in Vesalius’ time

Aristotle’s attempt to classify all animals known to him in his Historia Animālium (History of Animals) made him the earliest natural historian whose written work survives. He grouped animals according to their morphological and behavioral similarities (e.g., bloodless animals vs. those with blood; water animals vs. land animals; animals with feathers, wings, and beaks vs. those without) (Tilton, 2009). Aristotle’s felt that all living creatures had souls. In De Anima (On the Soul), he argued that the soul is the form, or essence, of any living creature and that it is not a distinct substance from the body that it is in (Sobol, 1993). This soul is not to be confused with the currently popular view of the soul as a spiritual entity that inhabits the body and, therefore, Aristotle's soul is sometimes translated as life force. The main part of De Anima is dedicated to the determination of the nutritive, sensitive, and rational souls. All species, plant or animal, must have a nutritive or vegetative soul to be able to nourish themselves and reproduce. All animals additionally have a sensitive soul that grants movement and sense. Aristotle regarded the ability to feel pleasure and pain as the simplest kind of perception. Only some animals possess more developed versions of all five senses and, therefore, the ability to distinguish objects in a complex way. As such, Aristotle provided the first written reports of mutualistic relations between individual animals, of animal tool use, and of brood parasitism practiced by the common cuckoo. Still, he did not explain these abilities by any internal power of sense even though he “pointed out that animals seem to emulate humans in the qualities of their mental life” (p. 111) (Sobol, 1993). Only humans were considered to possess a rational soul or mind that provides the ability to reason, reflect, and realize rationally formulated projects. This capacity for deliberative imagination was singled out as the defining feature of humans in De Anima.

Based on Aristotle’s De Anima, the Persian scholar Avicenna (Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Al-Hasan ibn Ali ibn Sīnā, c.980–1037) developed a theory of instinct in his Kutab al shifa (or Sufficientiae). This elaboration of the Aristotelian view on the lack of animal rational abilities was adopted by Roger Bacon (c.1219–c.1292), by Albertus Magnus (c.1200–1280) and his student Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), and by John Duns Scotus (c.1266–1308) (Sobol, 1993). Thus, Aristotelian views were fully accepted in the Middle Ages (Table 1). While the use of the Latin term rational animal for humans originated in medieval scholasticism, it reflected the Aristotelian view of humans as distinguished by a rational principle. Thereafter, the Jesuits of Coimbra (in their In Octo Libros Physicorum Aristotelis Stagirita of 1602) and Franciscus Suarez in particular (in his De Anima of 1621) were among the many Christian scholars who contributed to, and preserved, the Aristotelian legacy of interpretation of animal instinct, up until the Renaissance (Richards, 1987).

Because no work on zoology of similar detail to Aristotle’s work had been attempted until the 16th century, the Aristotelian concepts remained highly influential for some 2,000 years (Sobol, 1993; Tilton, 2009). Only in 1580 did the French philosopher Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (1533–1592) start to publish his Essays in which he argued, among many other theses, that animals had rational abilities comparable to those of humans. Still, Andreas Vesalius argued the existence of animal rational abilities some 40 years earlier in his De Fabrica.

Vesalius and his view on animal cognition

Vesalius (Andries van Wesel) was born in Brussels to a family of skilled physicians that cherished a lasting relationship with the rulers of the House of Habsburg for at least four generations. His father was the apothecary of King Charles V, who would later become the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Vesalius studied in Louvain, Paris, and later again in Louvain to become Bachelor in Medicine. He was taught and trained in the anatomical and physiological theories of Galen (c.129–c.200/c.216 AD) (Lanska, 2015). In Vesalius’ time, such teaching was still done in Medieval tradition with a professor anatomiae declaring Galen’s teachings from a pulpit, while a barber-surgeon performed possible dissections of dogs, pigs, and, sometimes, human corpses. One of the few exceptions to that rule was Jacobus Sylvius (Jacques Dubois; 1478–1555) who taught a 3-year course of medicine in the de Tréguier in Paris, which Vesalius attended. Sylvius was an ardent Galenist but he did his own dissections. Like Galen, however, he predominately dissected animals as he had no human corpses at his disposal. Only occasionally may he have brought the arm or a leg of an executed convict to his demonstrations (Lindeboom, 1975).

In December of 1537, Vesalius took his Medical Doctorate magna cum laude in Padua, Italy, to be appointed Professor of Anatomy a few days after. Vesalius’ subsequent extensive dissecting of human corpses taught him that Galen’s theories failed in many aspects, mostly because Galen had only dissected animals. During his public dissections, Vesalius saw no problem in intellectual clashes with older authoritarian Galenists and, in his De Fabrica, he mentioned and corrected over 200 of Galen’s mistakes (Eriksson, 1959; Garrison, 2015). In this way, Vesalius initiated the overthrow of 1,350 years of Galenic anatomical dogmas. We found that Vesalius, likewise, did not hesitate to doubt some 1,900 years of Aristotelian theory that had accumulated in the Christian dogma of humans being the only rational animals. Again on the basis of comparative anatomy he concluded in the seventh book of his De Fabrica entitled Devoted to the brain as the seat of the animal faculty and to the sense organs, that at least the “higher” animals must have a mind similar to humans including some sort of rational soul (Richardson & Carman, 2009). Here, we present Vesalius’ arguments for this conclusion.

In the chapter entitled The brain was constructed for the soul-in-chief, for our senses, and for movement dependent on our own whim, Vesalius mentioned that he “did not agree with the teachings of the Stoics and Peripatetics to the extent of locating the animal principle in the heart or saying that the nerves take origin from the heart. We have still to deal with the source of sensation, of voluntary movement and of the soul-in-chief (by means of which we imagine, reason and remember), and that is therefore the subject of the present book, which will describe the brain and all its parts along with the organs of the senses” (p. 161) (Richardson & Carman, 2009). Note that Vesalius’ understanding of the concept “soul-in-chief” (in casu the ability to image, reason and remember) featured the basics of our current understanding of the concept “cognitive control” (in casu the ability to actively create an information picture that guides behavior based on experience and knowledge).

In the same chapter, Vesalius recalled the Aristotelian principles of his training: “I have not yet forgotten something that I heard when I was a student of natural science in the Castle School, the most important and famous wing of the university at Louvain. Our teacher was a theologian by profession and therefore, of all the academic staff in that university, the most inclined to mix religious teachings with scientific. He was reading to us commentaries on Aristotle's On the Soul, and in these it was written that the brain has three ventricles of which the first is in the front, the second in the middle and the third at the back. In addition to names derived from their positions they have other names derived from their function. The first, or anterior, ventricle, which was said to be in the forehead, was called the ventricle of the common sense, because from it the nerves of the senses travel to their organs, and because by means of these nerves odors, colors, flavors, sounds and tactile qualities are conveyed to this so the authors of these commentaries thought! They thought that the main function of the first ventricle was to receive things transmitted by the senses (popularly grouped together as the common sense) and pass them on to the second ventricle by a channel linking the two, so that the second ventricle could imagine, reason or think about the thing transmitted; thought or reasoning was therefore attributed to this second ventricle. The third ventricle was sacred to memory; in it the second ventricle, having abundantly mulled over the things transmitted to it, would deposit all such portions of them as it wanted to retain. If this third ventricle is moister like wax, things can quickly be engraved in it; if it is drier like hard stone the engraving process is slower. This means that in proportion to the ease or difficulty of the engraving this ventricle would preserve for a shorter or longer time what was entrusted to it, so these commentaries said! But this third ventricle did not retain or form likenesses of these things for its own purposes or its own benefit, but rather for the sake of the second ventricle, so that whenever the second ventricle began to reason on some subject that had been entrusted to the sinus of memory this sinus could swiftly dispatch it, whatever it was, to the second ventricle, as to a sort of factory of reason, for processing” (p. 164) (Richardson & Carman, 2009).

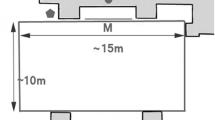

Vesalius continued that “to help us grasp each point in which we were being instructed we were shown a diagram taken from some pearl of philosophy. This diagram depicted the aforesaid ventricles, and we students copied it down in our notebooks with accuracy in proportion to our interest in scholastic drawing. We were persuaded that it showed, not merely the three ventricles, but all the parts, not merely of the brain but of the whole head” (p. 164) (Richardson & Carman, 2009). Subsequently, he set out to correct this dogma by stating: “But the whole thing was a figment of the imagination of people who had never seen the brilliance of our Creator in the fabric of the human body; the following account will show how wrong their account of the structure of the brain was” (p. 165) (Richardson & Carman, 2009).

Further, Vesalius provided the detailed anatomy of the cerebrum and cerebellum and discussed the morphology and function of the ventricles. After having done so, he commented that there cannot “be anyone (excepting disciples of Albertus [Magnus], Thomas [of Aquino], [John Duns] Scotus, and that gang of theologians) who could be persuaded that one of the worms [the anterior and posterior parts of the vermis cerebelli] (for they cannot both be used to close a single orifice) controls the channel so as to allow phantasms to enter into the seat of memory .[..]. and then transmit them, like thieves fettered in the jailhouse of memory, into the middle ventricle, which they regard as the seat of reason. In that case God the Creator of the world would in vain be providing the dog, the sheep, and other such animals with wormlike processes [lingula cerebelli and uvula vermis], since (according to them) these animals have no faculty of reason” (p. 208-209) (Richardson & Carman, 2009). With this comment, Vesalius introduced his argument of anatomical form as indicative of physiological function.

Obviously, Vesalius thought differently with regard to the animals having faculty of reason, and in a paragraph entitled The structure of the animal brain does not differ from the human, he noted that “it is a fact that the brain of a sheep, a goat, an ox, a cat, an ape, a dog and even of certain birds that I have dissected shows virtually no difference from the human brain in respect of the conformation of the parts, and especially in respect of the ventricles. We do, however, know that there is a difference in size according to the amount of reason that they seem to possess: man's brain is the largest, followed by the ape's, the dog's, and so on, corresponding to the amount of rational force that we deduce each animal to have. The size of the human brain is not proportional to the size of the body, for man's brain is larger than that of any other animal: it is larger than the brains of two horses or two oxen or two donkeys” (p. 165) (Richardson & Carman, 2009). This observation echoed some 330 years later through Darwin’s conclusion that “the difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind” (p. 837) (Darwin & Wilson, 2010).

Vesalius continued that “all this, along with the fabric of the ventricles, [was to] be made perfectly clear” by his anatomical dissections (p. 165) (Richardson & Carman, 2009). He felt he could “demonstrate the functioning of the brain by the vivisection of animals with a high degree of truth and probability. But as to how the brain performs its task in respect of imagining, reasoning, thinking and remembering (or however else you like to subdivide and enumerate the powers of the soul-in-chief in conformity with someone else's teachings) I have reached no satisfactory conclusions. I have examined the parts of the brain unceasingly and in the utmost detail and have observed all other parts of the body whose function is apparent to even a passing examination in the course of dissection; but whatever analogy I should come up with as a result of this or whatever likelihood should arise in my mind could not be set down without damaging our most holy faith” (p. 163) (Richardson & Carman, 2009). This way of reasoning for the existence of animal cognition may be seen as an argument from analogy (Andrews, 2008 (revised 2016)). This argument can be formulated as: (1) The species I already know to have cognition (i.e., humans) have three ventricles; (2) (Higher) animal have three ventricles; (3) Therefore, (higher) animals probably have cognition.

On more than one occasion, Vesalius indicated being fully aware of “the degree of impiety that my description of the function of the cerebral ventricles (so far as the powers of the soul-in-chief are concerned) will bring to beginners whose minds are not yet strong in our most holy faith: this point can be pondered by those who have learnt that the brains of quadrupeds closely resemble human brains in every respect, despite the fact that, on the basis of the teachings of theologians, we deny to the animal brain all power of reasoning and indeed a rational soul” (p. 165) (Richardson & Carman, 2009). Therefore, “in examining the brain and its parts there is nothing to be gained by vivisection since here, whether we like it or not, we are required by the theologians of our own day to deny that dumb animals have memory, reason or thought, even though the construction of their brain is the same as that of the human one. Hence the anatomy student who is well versed in dissection of the dead and not infected by any heresy well understands what a mess I should get myself in if I were to say anything about vivisection of the brain, much as I should like to do so” (p. 269-270) (Richardson & Carman, 2009). Thus, Vesalius concluded the part on the function of the ventricles with the remark that “I cannot say anything about the areas in the brain occupied by the faculties of the soul-in-chief (though the people who nowadays like to be called theologians and consequently think that there are no limits to their powers allot these as well). All the theologians of our own time flatly deny that apes, dogs, horses, sheep, cattle and similar animals have the principal powers of the soul-in-chief [imagining, reasoning, and remembering] and state that humans alone have (to say nothing of others) the faculty of reason and that (if I understand them correctly) all humans have this to an equal degree. Yet our dissections reveal that animals have the same number of ventricles as humans; and not only is the number the same but they are alike in every other respect as well except size and the integrity and accuracy of their temperament. Even for the sake of these humans, therefore, let me hold aloof from inquiring any further into the function of the ventricles” (p. 198-199) (Richardson & Carman, 2009).

This conclusion resonated in Frans de Waal’s summary of The Cambridge Declaration on Animal Consciousness (Low et al., 2012): “that given the similarities in behavior and nervous systems between humans and other large-brained species, there is no reason to cling to the notion that only humans are conscious. As the document puts it, "The weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness”” (p. 234) (de Waal, 2016).

Early modern thinkers’ view on animal cognition

Even though Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras (c.580–c.500 BC), Aristotle’s pupil Theophrastus (c.371–c.287 BC), Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD), and Plutarch (c.45–c.120 AD) had defended the notion that animals had cognitive abilities (Charalampous, 2016), the Aristotelian denial of such abilities was to dominate Western intellectual thought for some 2,000 years (Tilley, 1993). Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (1533–1592) was the first philosopher to be heard when he posited that animals are fully cognitive creatures and that their societies are not so different from ours. He is generally considered the first to lastingly posit this view (Charalampous, 2016). Allegedly, his view on animal cognition reflected “an increasing tendency in the early modern period to credit animals with reason, intelligence, language and almost every other human quality” (p. 29) (Charalampous, 2016). Other early modern thinkers immediately recognized that de Montaigne’s thesis on animal cognition was inextricably linked to human nature and the theological discourses pertaining to the problem of the human soul’s (im)mortality. Obviously, this led to fierce debate. De Montaigne’s ideas needed be defended against critics who accused him of promoting the un-Christian idea that the human soul is mortal due to its intimate connection to the material body (Charalampous, 2016). On the one hand, Etienne Pasquier (1529–1615), Hieronymus Fabricius ab Aquapendente (c.1533–1619), Pierre Charron (1541–1603), Francis Bacon (1561–1626), Marie de Gournay (1565–1645), John Hagthorpe (1585–c.1630), Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655), and Marin Cureau de la Chambre (1594–1669) strongly supported de Montaigne’s natural philosophy (Charalampous, 2016; Richards, 1979). On the other, Joseph Justus Scaliger (1540–1609), René Descartes (1596–1650), Jean de Silhón (1596–1667), Charles Cotton (1630–1687), John Locke (1632–1704) and Nicolas Malebranche (1638–1715) vigorously refuted his views (Charalampous, 2016; Richards, 1987).

Some 90 years after De Fabrica, Descartes formulated his views on the rational soul. In a letter to the Marquess of Newcastle, Descartes explicitly states his disagreement with de Montaigne’s attribution of “understanding or thought to animals” (p. 28) (Charalampous, 2016). Like the Aristotelians, Descartes separated humans from animals, but he did so more decisively. Descartes presented his arguments in l’Homme (1630–1633), which was only published posthumously in a Latin translation in 1662 as a consequence of Descartes’ fear for condemnation by the Roman Catholic Inquisition, such as Galileo Galilei experienced in 1633 (Bitbol-Hespériès, 2000). For Descartes and other Cartesians, animals did not have reason or intelligence but mimicked intelligent action. Animals, they felt, do not lack sensations or perceptions but still operate as mere machines: brutes functioning purely mechanically according to the laws of physics (Richards, 1979). Aristotelians and Cartesians differed profoundly on the ultimate principles of animal psychology. They nonetheless agreed that complex animal behavior should be explained by appeal to instincts that they understood as blind, innate urges instilled by the Creator for the welfare of his creatures (Richards, 1987).

Descartes extensively corresponded with the French theologian, philosopher, and mathematician Marin Mersenne (1588–1648), an ordained priest who had many contacts in the scientific world and may be viewed as “the center of the world of science and mathematics during the first half of the 1600s” (p. 59) (Bernstein, 1996). Mersenne was not afraid to create disputes among his many learned friends, and, in 1642, he engaged the French priest, philosopher, and mathematician Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655) in a controversy with Descartes. Gassendi undertook a comparative study of animal and human cognitive abilities in his Syntagma philosophicum (Philosophical treatise, published posthumously in 1658) to conclude that these were logically similar: both human and animal souls operated on sensory images to yield reasoned actions (Richards, 1979). His objections to the fundamental propositions of Descartes appeared in print in 1642. They did not include any citation of Vesalius’ comments on the subject. Still, 50 years after de Montaigne, a second philosopher influentially supported Vesalius’ original views on animal cognition by forcefully opposing the Aristotelian and Cartesian interpretation that complex animal behavior should be explained only by appeal to instincts (Richards, 1987). John Ray (1627–1705), Steno (Niels Stensen; 1638–1686) and Mann Cureau de La Chambre (1594–1669), an associate of Gassendi, agreed, and sensationalists were reticent about the use of instinct as the sole explanation of animal behavior through the next century (Richards, 1987). Meanwhile, however, Vesalius’ original text of De Fabrica had increasingly became obscured. With that, his innovative thoughts on the animal soul-in-chief were no longer known. In Vesalius’ time, the prime interest in his illustrations, rather than his texts, may have been explained by the novelty of illustrating anatomical texts. A century later, medical doctors may have been so proud of their own medical advancements that they preferred to regard texts of their predecessors as outdated (Elkhadem et al., 1993). In our era, the neglect of Vesalius’ texts may have resulted from difficulty in coming to grips with his Latin grammar (Richardson & Carman, 1994; Lydiatt & Bucher, 2012; Lanska, 2014). Although many editions, revisions, adaptations, and facsimiles of his work appeared over the centuries, it was never integrally translated into a modern language other than Russian. The English translation presented by Richardson and Carman between 1998 and 2009 supplies an accessible version of the entire monumental work for the first time (Richardson & Carman, 1998; Richardson & Carman, 2009). Since, the study of the unique combination of Vesalius’ text and illustrations of all seven books of De Fabrica has become readily available again.

Vesalius and the changing view on animal cognition

Because of his De Fabrica, Andreas Vesalius is generally considered a genius (Lydiatt & Bucher, 2012). Genius, in general, does not acknowledge authority. The true genius is well informed on what authority proclaims, but does not unquestioningly accept these proclamations as dogmas, or even as granted. Only if acceptable to their own independent intelligence and deduction, do geniuses accept a thesis or a way of reasoning. Thus, Vesalius felt that “everyone who has not surrendered to the authorities but believes in the truth will agree with me” (p. 191) (Garrison, 2015). This implicit doubt of all that is generally accepted, but never proven, to be truth is obvious from Vesalius texts. Even at age 27, Vesalius did not shy from fulminating against the separation of internal medicine, surgery, and pharmacy, customary in his era (as it is today). In the preface of De Fabrica that was directly addressed to no one less than the “most noble emperor Charles,” Vesalius expressed being sure of his view that the “threefold approach to healing cannot be broken up and the whole of it is the province of each individual practitioner” (p. x) (Richardson & Carman, 1998). Likewise, he eventually parted from the Galenic tradition of his training because his observations no longer supported it: “I cannot set bounds to my astonishment at my own stupidity and excessive trust in the writings of Galen and other anatomists” (p. 217) (Richardson & Carman, 2009). Vesalius demonstrated the flaws in the work of these previous anatomists and, in particular, Galen, and proved that human anatomy could not be derived solely from animal anatomy. Rather, it has to be seen with the bare eye in human cadavers. He confessed to have been “so besotted by Galen that I had never undertaken to demonstrate a human head without the head of a lamb or ox at my public dissections; I was so keen not to gain the reputation of having been unable to find the plexus whose name was familiar to everyone that I imposed upon my audience by demonstrating from a sheep's head something I had never found in a human one” (p. 217) (Richardson & Carman, 2009). Thus, the instruction of the ardent Galenist Sylvius to perform all anatomical dissections by yourself paradoxically led to the overthrow of Galenic authority. Although most of Vesalius’ medical contemporaries had only the important ancient texts as the weight of their authority, the anatomists had the dissected body to confirm or contradict the authorities. Vesalius was explicitly placing all this in front of the medical authorities of his time with little talent for diplomacy (Lydiatt & Bucher, 2012). The clash of the older authoritarian Curtius and the young brazen Vesalius that was minutely recorded by Heseler in his eyewitness report of a public dissection in Padua, Italy (Eriksson, 1959), showed the clear dichotomy between the traditional medieval anatomy that had been sustained by scholasticism and the revolutionary Renaissance anatomy based on direct observation that was introduced and championed by Vesalius – a difference manifestly evident to the students present (Lanska, 2014).

The French philosopher de Montaigne was born only a decade before Vesalius first published De Fabrica. By the time he started writing his Essays in 1572, de Montaigne spent most of his days in his library that is said to have held 1,000 historical and contemporary medical and philosophical books (Bernoulli, 1992). No doubt Vesalius’ De Fabrica was one of these. Like Vesalius, de Montaigne was taught by Sylvius in Paris and (Bernoulli, 1992; Hoffmann, 2005), therefore, very likely knew that this ardent Galenist fiercely rejected De Fabrica. However, rather than busying himself with Galen’s observations, de Montaigne reverted back to the pre-Galenic idea that each individual is capable of governing all aspects of his own life (Collier, 2013). As such, de Montaigne referred to works of Plutarch more than 400 times in his Essays and felt that the great medical innovators of his time, notably Paracelcus (1493–1541), Leonardo Fioravanti (1517–1588), and Giovanni Argenterio (1513–1572), were changing the medical paradigm for the worse (Kimball, 2000). His not including Vesalius in this regard suggests that de Montaigne, just like Vesalius himself, felt that Vesalius’ work was an act of renaissance within the existing contemporary paradigm, rather than a revolution against it (Robert, 2015). Even though de Montaigne never cited, or referred to, Vesalius’ observations on similar cognitive functions of the similar human and animal cerebral anatomy, it is more than likely that he knew (of) these observations. De Montaigne may even have been inspired by Vesalius’ observations when he posited that animals are fully cognitive creatures. Some 50 years after de Montaigne, Descartes arrived at his arguments after having “taken into consideration not only what Vesalius and the others write about anatomy, but also many details unmentioned by them, which I have observed myself while dissecting various animals” as off 1629 (p. 353) (Bitbol-Hespériès, 2000). He did not cite any of Vesalius’ original texts but acknowledged the influence that Vesalius’ work had on his reasoning. Thus, Descartes’ work on animal cognition is to be considered as part of a continuous line in the evolution of anatomical and physiological knowledge from Vesalius onwards (Bitbol-Hespériès, 2000). For these reasons, we conclude that Andreas Vesalius was instrumental in breaking with two millenniums of dominance of the various concepts of lack of animal cognition, just as he was instrumental in breaking with the 1,350-year-old Galenic concepts of human anatomy and physiology.

Data Availability

None of the data or materials for the experiments reported here are available, and none of the experiments was preregistered.

References

Allen, C. (1995 (revised 2015), 10 Jun, 2015). Animal Consciousness. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consciousness-animal/#hist

Andrews, K. (2008 (revised 2016), 6 May, 2016). Animal Cognition. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cognition-animal/

Bekoff, M., Allen, C., & Burghardt, G. M. (2002). Introduction. In M. Bekoff, C. Allen, & G. M. Burghardt (Eds.), The cognitive animal: Empirical and theoretical perspectives on animal cognition. (pp. ix-xvi). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bernoulli, R. (1992). Montagne and Paracelcus - Ein Essay von René Bernoulli. Gesnerus: Swiss Journal of the Historie of Medicine and Sciences, 49(3-4), 311-322.

Bernstein, P. L. (1996). Against the Gods - The remarkable story of risk. New York, NY: Wiley.

Bitbol-Hespériès, A. (2000). Cartesian physiology. In S. Gaukroger, J. Schuster, & J. Sutton (Eds.), Descartes' Natural Philosophy (pp. 349-382). London, UK: Routledge.

Charalampous, C. (2016). Rethinking the Mind-Body relationship in early modern literature, philosophy and medicine - The Renaissance of the body (1 ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Collier, C. (2013). From astrology to the cult of dissection: The Renaissance. In C. Collier (Ed.), Recovering the body - A philosophical story (pp. 105-132). Ottawa, Can: University of Ottawa Press.

Darwin, C., & Wilson, E. O. (2010). From so simple a beginning - Darwin's four great books Voyage of the Beagle, The Origin of Species, The Descent of Man, and The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

de Waal, F. (2016). Are we smart enough to know how smart animals are? (1 ed.). New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Elkhadem, H., Heerbrandt, J. P., Wellens-De Donder, L., Walch, N., Dumortier, C., & de Meeus d'Argenteuil, A. (1993). Andreas Vesalius. In Andreas Vesalius - Experiment en onderwijs in de anatomie tijdens de 16de eeuw (pp. 3-30). Brussel, BE: Koninklijke Bibliotheek Albert I.

Eriksson, R. (1959). Andreas Vesalius' first public anatomy at Bologna 1540 - An eyewitness report by Baldasar Heseler, medicinae scolaris. Uppsala, Sweden: Almqvist & Wiksells Boktryckeri.

Garrison, D. H. (2015). Vesalius: The China root epistle - A new translation and critical edition. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Hoffmann, G. (2005). The investigation of nature. In U. Langer (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Montaigne (pp. 163-182). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kimball, R. (2000). Plutarch and the issue of character. New Criterion, 19(4), 4.

Lanska, D. J. (2014). Vesalius on the anatomy and function of the recurrent laryngeal nerves: medical illustration and reintroduction of a physiological demonstration from Galen. J Hist Neurosci, 23(3), 211-232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0964704X.2014.884885

Lanska, D. J. (2015). The evolution of Vesalius's perspective on Galen's anatomy. Istoriya meditsiny (History of Medicine), 2(1), 13-32.

Lindeboom, G. A. (1975). Andreas Vesalius and his Opus Magnum - A biographical sketch and introduction to the Fabrica. Nieuwendijk: de Forel.

Low, P., Panksepp, J., Reiss, D., Edelman, D., van Swinderen, B., & Koch, C. (2012). The Cambridge declaration on consciousness. Retrieved from http://fcmconference.org/img/CambridgeDeclarationOnConsciousness.pdf

Lydiatt, D. D., & Bucher, G. S. (2012). The influence of the final cause doctrine on anatomists of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries concerning selected anatomical structures of the head and neck. Laryngoscope, 122 Suppl 3, S35-51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23391

Richards, R. J. (1979). Influence of Sensationalist tradition on early theories of the evolution of behavior. J Hist Ideas, 40(1), 85-105.

Richards, R. J. (1987). Origins of evolutionary biology of behavior. In Darwin and the emergence of evolutionary theories of mind and behavior (pp. 20-70). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

Richardson, W. F., & Carman, J. B. (1994). On translating Vesalius. Med Hist, 38(3), 281-302.

Richardson, W. F., & Carman, J. B. (1998). Andreas Vesalius On the fabric of the human body, Book I: The bones and cartilages. San Francisco, CA: Norman Publishing.

Richardson, W. F., & Carman, J. B. (2009). Andreas Vesalius On the fabric of the human body, Book VI: The heart and associated organs, and Book: VII The brain (1 ed. Vol. V). Novato, CA: Norman Publishing.

Robert, J. (2015). Pa/enser bien le corps: Cognitive and curative language in Montaigne's Essays. J Med Humanit, 36(3), 241-250.

Sobol, P. G. (1993). The shadow of reason. In J. E. Salisbury (Ed.), The medieval world of nature - A book of essays (pp. 109-128). New York, NY: Garland.

Tilley, M. A. (1993). Martyrs, monks, insects, and animals. In J. E. Salisbury (Ed.), The medieval world of nature - A book of essays (pp. 93-107). New York, NY: Garland.

Tilton, L. (2009). From Aristotle to Linnaeus: the History of Taxonomy. Retrieved from http://davesgarden.com/guides/articles/view/2051/

Vesalius, A. (1543). De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem. Basel: Operinus.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All four authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brinkman, R.J., Hage, J.J., Oostra, RJ. et al. Andreas Vesalius (1515-1564) on animal cognition. Psychon Bull Rev 26, 1588–1595 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-019-01643-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-019-01643-4