Abstract

The keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice are two cognitive techniques that have each been identified to enhance foreign language vocabulary learning. However, little is known about the use of these techniques in combination. Previous demonstrations of retrieval-practice effects in foreign language vocabulary learning have tended to use several rounds of retrieval practice. In contrast, we focused on a situation in which retrieval practice was limited to twice per item. For this situation, it is unclear whether retrieval practice will be effective relative to restudying. We advance the view that the keyword mnemonic catalyzes the effectiveness of retrieval practice in this learning context. Experiment 1 (48-h delay) partially supported this view, such that there was no testing effect with retrieval practice alone, but the keyword-retrieval combination did not promote better retention than keyword alone. Experiments 2 and 3 (1-week delay) supported the catalytic view by showing that the keyword-retrieval combination was better than keyword alone, but in the absence of keyword encoding there was no retrieval practice effect (replicating Experiment 1). However, with four rounds of retrieval practice, a marginally significant testing effect emerged (Experiment 3). Moreover, the routes through which participants reached each answer were identified by asking retrieval-route questions in Experiments 2 and 3. Keyword-mediated retrieval, which was observed sometimes even in no-keyword instructed conditions, was shown to be more effective than unmediated retrieval. Our findings suggest that incorporating effective encoding techniques prior to retrieval practice could augment the effectiveness of retrieval practice, at least for vocabulary learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

What is the best way to learn foreign language vocabularies? This was the question posed by the inaugural Memrise Prize, an international competition to discover the best protocols for learning various types of information (memprize.com). Each contestant submitted their best 1-h long lesson to teach 80 Lithuanian-English word pairs for a test 1 week later. A couple of common ingredients emerged among the five finalists, who were chosen according to their lessons’ effectiveness demonstrated through experiments – the keyword mnemonic (four out of the five) and retrieval practice (all five; Potts, Shanks, Cooke, & Whately, 2016). As we briefly review next, each technique has been shown to be a potent facilitator of learning foreign-language vocabulary. Less attention, however, has focused on the potential benefit of combining the two techniques. In this article we consider several theoretical alternatives regarding the value of combining both techniques relative to relying on either technique alone, and present three experiments to evaluate these alternatives.

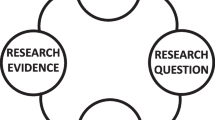

The keyword mnemonic is a memory-enhancing technique that incorporates identification of a keyword and utilization of imagery to create a strong retrieval route (Atkinson, 1975; Atkinson & Raugh, 1975; Raugh & Atkinson, 1975). In foreign language vocabulary learning, learners identify (or are given) a familiar word (the keyword) within a to-be-learned foreign word and create an interactive image between the keyword and the English translation of the foreign word. For example, a learner may see the Lithuanian word, burna, meaning mouth, identify an English keyword, burn, and then create an image of burning her mouth. Later, when she sees burna, she would identify the keyword, burn, recall the image she created, and reach the English translation of mouth (see Putnam, 2015, for a recent review).

The effectiveness of the keyword mnemonic has been experimentally demonstrated in a variety of languages such as French, German, Italian, Latin, Russian, Spanish, and Tagalog (see Dunlosky, Rawson, Marsh, Nathan, & Willingham, 2013, for a review). College students varying in foreign language learning ability, as well as children as young as fifth grade, benefit from the keyword mnemonic (Pressley et al., 1980; Pressley, Levin, & Miller, 1981). In laboratory experiments, the keyword mnemonic has proven more effective in teaching new vocabulary items than presenting the items in semantic context (McDaniel & Pressley, 1984, 1989), a “natural language” method that some have advocated (e.g., Gipe, 1978; Sternberg, Powell, & Kaye, 1983). Moreover, students who spontaneously use the keyword mnemonic have a higher GPA than those who do not (Carlson, Kincaid, Lance, & Hodgson, 1976), and GPA is positively correlated with students’ familiarity with the keyword mnemonic (McCabe, Osha, Roche, & Susser, 2013).

Another effective and well studied cognitive operation that enhances retention is retrieval practice (see Roediger & Butler, 2011, for a review), and its benefits on foreign language vocabulary learning have also been widely documented. A variety of retrieval practice experiments (i.e., testing effect experiments) have demonstrated the memorial benefits of retrieval practice using foreign words and their English translations, such as Eskimo (Carrier & Pashler, 1992), Swahili (e.g., Karpicke & Roediger, 2008), and Lithuanian (e.g., Vaughn, Rawson, & Pyc, 2013). Retrieval practice is better than not only restudying (e.g., Karpicke, 2009) but also repeated studying incorporating elaboration (Karpicke & Smith, 2012). Retrieval practice is more effective than restudying even when participants are highly motivated via monetary incentive (Kang & Pashler, 2014). Further, children as young as 12 years of age can benefit from retrieval practice when learning foreign language vocabulary (Fritz, Morris, Acton, Voelkel, & Etkind, 2007).

Combining the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice

Given the effectiveness of the keyword mnemonic and of retrieval practice, a potentially promising but little studied method might be to combine these two techniques. From a practical perspective, these two techniques are easy to combine. During study learners can implement the keyword mnemonic and then subsequently practice retrieving the meaning (ideally using the keyword; Pyc & Rawson, 2010) when given the list of vocabulary items (e.g., using flashcards). Theoretically, the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice in combination would appear to augment the encoding and retrieval components, respectively, of foreign-language vocabulary learning. In particular, the keyword mnemonic helps to enhance associative encoding between the vocabulary item and its meaning. A challenging aspect of vocabulary learning is that the association between the lexical unit and its meaning is arbitrary, and arbitrary associations are difficult to learn (see; Pressley, McDaniel, Turnure, Wood, & Ahmad, 1987; Stein & Bransford, 1979). The keyword mnemonic (and mnemonics in general) is effective because it constructs a meaningful associative elaboration between the keyword embedded in the vocabulary item and the item’s meaning (see Levin & Levin, 1990, for theoretical elaboration).

While the keyword mnemonic can be viewed as an encoding mnemonic (Bellezza, 1987), retrieval practice can be viewed as generally strengthening later retrieval (possibly through increasing storage strength – Bjork & Bjork, 1992; or through facilitating early generation of the associated target during the recall process, thereby precluding a possibly error-prone generation-recognition process – Jacoby & Hollingshead, 1990; Thomas & McDaniel, 2013). More specifically with regard to the present learning task, retrieval practice appears to stabilize the use of an initially encoded associative mediator to guide retrieval. For instance, Pyc and Rawson (2010) had participants learn Swahili-English pairs with three rounds of retrieval or restudying after initial study. During the initial study as well as the subsequent rounds of learning, participants were asked to come up with a keyword for each pair. On a 1-week delayed test, the participants who learned the pairs through retrieval were more likely to recall their keywords than the participants who learned them through restudying (51% vs. 34%). Second, when keywords were recalled at the final test, participants who learned the pairs through retrieval were more than twice as likely to correctly recall the target (i.e., the English translation) as the participants who learned through restudying. That is, retrieval practice increased the likelihood of using the keyword mediator as well as increasing the effectiveness of the keyword in recovering the vocabulary item meaning.

Thus, based on the above considerations and findings, a plausible theoretical idea is that the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice have complementary effects (we term this the complementary view for purposes of exposition). According to this view, when both techniques are implemented in foreign vocabulary-learning, the individual effects of the keyword and retrieval practice techniques will combine to produce better learning than either alone.

A second theoretical possibility is that the two techniques have somewhat overlapping effects. For instance, one view is that retrieval practice enhances memory by stimulating elaboration (Kang, 2010; McDaniel & Masson, 1985; Roediger & Butler, 2011). According to this view, the process of cue-guided retrieval involves generating elaborative information that might provide additional retrieval routes to the target. Essentially, a variety of concepts related to the cue are activated in the service of retrieval of the target. When the cue is later presented on a subsequent test, these elaborations now provide additional links between the cue and the target. Essentially, initial retrieval might create mediating links, much as the keyword mnemonic does, and accordingly the two techniques might serve somewhat redundant encoding functions. Moreover, the keyword mnemonic is assumed to itself facilitate retrieval because the keyword is a readily available cue (when given the vocabulary item) to guide retrieval, and thus perhaps the two techniques also serve somewhat redundant retrieval functions. The upshot is that this view (which we label the redundancy view) anticipates that combining the two methods will not be more effective than relying solely on one technique (cf. McDaniel, Einstein, & Lollis, 1988).

The third theoretical possibility particular to the current experiments is that low dosages of retrieval practice will enhance foreign language learning, but only when combined with some other means of mnemonic support (the keyword mnemonic in our case). To foreshadow, the participants in the current experiments engaged in retrieval practice twice per item after a single initial exposure (except for some conditions in Experiment 3). Extant experiments have reported that retrieval practice enhances retention of foreign-language vocabulary meanings (Carpenter, Pashler, Wixted, & Vul, 2008; Carrier & Pashler, 1992; Jönsson, Kubik, Sundqvist, Todorov, & Jonsson, 2014; Kang & Pashler, 2014; Karpicke, 2009; Keresztes, Kaiser, Kovács, & Racsmány, 2014; Toppino & Cohen, 2009; Vestergren & Nyberg, 2014); however, these paradigms tended to use relatively high dosages of retrieval practice (e.g., Kang & Pashler, 2014: four times per item; Keresztes et al., 2014: six times per item), multiple initial exposures (Jönsson et al., 2014: three times; Toppino & Cohen, 2009: four times in Experiment 1 and eight times in Experiment 2), or criterion learning (i.e., participants engage in repeated retrieval practice during the initial learning phase until they reach a certain proficiency, such as correctly recalling all items once; e.g., Karpicke, 2009). Accordingly, it remains uncertain whether modest retrieval practice (two rounds per item in the current experiments) after a single initial exposure enhances retention for foreign vocabulary. An initial study suggests that limited retrieval practice may not reliably benefit foreign-vocabulary learning. Kang and Pashler (2014) tested participants either twice or four times after a single initial exposure to Swahili-English pairs. Though their four-time testing conditions showed test-enhanced learning, their two-time testing condition did not show test-enhanced learning consistently across three experiments.

For present purposes, the provocative possibility is that modest retrieval practice (two times per item in our case) is effective only when combined with the keyword mnemonic. The idea is that provision of a keyword during initial study catalyzes the benefits of subsequent retrieval; in particular, the keyword provides a retrieval route that can be solidified through minimal retrieval practice (we label this the catalytic view). Recent results from a large study on individual differences in the testing effect for learning foreign vocabulary (Swahili) offer preliminary encouragement for this catalytic hypothesis. Learners high in fluid intelligence (gF) were more likely to report spontaneously using the keyword strategy relative to learners lower in gF, and the high gF learners also displayed a more robust testing effect for difficult vocabulary items relative to low gF learners (Minear, Coane, Boland, Cooney, & Albat, 2018). Clearly, these patterns are correlational and only suggestive in terms of a catalytic hypothesis.

Studies combining retrieval practice with keyword encoding

Only a handful of studies have addressed this important question of whether the combination of the keyword and retrieval practice techniques is better than either the keyword mnemonic or retrieval practice alone. We consider the few existing studies that have implemented a combined keyword-retrieval practice condition, and then report three experiments that inform the theoretical alternatives developed above.

In a learning task similar to foreign language learning (learning the arbitrary associations between first and last names), Morris, Fritz, Jackson, Nichol, and Roberts (2005, Experiment 1) reported that combining retrieval practice with a strategy similar to the keyword mnemonic produced higher performance than retrieval practice by itself. Participants had to learn a first- and last-name association with repeated retrievals with or without initial semantic association instructions. Participants in the semantic association condition were instructed to identify meanings associated with names. For example, some names might be occupations (e.g., Cook, Baker) and others geographical locations (e.g., Lancaster, Washington). The instructions also identified using phonetic similarity, such as deriving “airman” from Herrman (much like the keyword mnemonic). After a 5-min delay, participants in the retrieval practice-only condition recalled 45% of the last names cued by the first names, whereas those in the retrieval practice and semantic association condition recalled substantially more last names (70%).

Fritz et al. (2007, Experiment 3) directly addressed the question of the relative merits of the keyword mnemonic, retrieval practice alone and the two in combination for learning new vocabulary. English-speaking children (12–13 years of age) studied English-German word pairs with elaboration (i.e., the control condition), retrieval practice, the keyword mnemonic, and a combination of retrieval practice and the keyword mnemonic (learning condition was varied within-subjects). They were tested immediately as well as after a 1-week delay in both receptive (German-?) and productive (i.e., English-?) tests. For the receptive test, which is the focus of the current paper, at both the immediate and delayed tests the retrieval practice, the keyword mnemonic, and the combined conditions were better than elaboration; however, these three conditions did not differ from each other (in line with the redundancy view).

Unfortunately, several methodological features limit the interpretability of this pattern. Because of the classroom context in which the experiment was conducted, all participants received the different learning conditions in the same order: elaboration, retrieval practice, keyword, and the retrieval-keyword combination. Thus, fatigue or carry-over effects may have minimized potential advantages of the combined condition. Second, this experiment’s focus was on learning to produce the foreign-language word (German) given the English meaning. Accordingly, the retrieval practice trials involved the presentation of an English word and required recall of the corresponding German word (production). This version of retrieval practice may not be optimal for combination with the keyword mnemonic because the keyword mnemonic is not designed to support performance on a production test of the foreign-language word (because the keyword mnemonic is based on identifying a keyword in a provided foreign word as a retrieval cue for producing the English word). Finally, it is uncertain how adult learners would fare with a combined retrieval practice and keyword mnemonic.

Karpicke and Smith (2012; Experiments 1 and 2) reported additional relevant results in an experiment on learning the meaning of unfamiliar vocabulary (e.g., “loggia”) from participants’ native language (English; vocabulary items used in McDaniel & Pressley’s, 1984, keyword study). On a 1-week delay test, repeated retrieval practice was better than studying with the keyword mnemonic (unlike Fritz et al., 2007), and adding the keyword mnemonic to repeated retrieval practice did not yield additional benefits over repeated retrieval practice alone. A possibly critical feature of these two experiments is that they employed criterion learning. Participants received repeated cycles of studying and testing (up to six but usually within four cycles) until all items (meanings) could be recalled correctly at least once. The strength of the keyword mnemonic may be that it provides strong retrieval routes early, thereby promoting efficiency of learning, but not necessarily advantaging retention when the learning context requires learning to criterion (McDaniel, Pressley, & Dunay, 1987). In addition, one interesting aspect of their study was that after participants were brought up to criterion, the keyword mnemonic did not improve learning, but retrieval practice did. This finding suggests that these two techniques improve learning through different mechanisms, which is contrary to the redundancy view.

To take stock, the three published studies examining the effects of combining an associative encoding mnemonic (keyword or keyword-like) with retrieval practice have not produced consistent patterns. One study found an advantage of combining the techniques (but using a first-last name-learning task), and two found no advantage relative to retrieval practice alone. Clearly, additional research is warranted, motivating the following experiments.

Experiment 1

We examined the relative efficacy of retrieval practice and the keyword mnemonic alone versus the combination of retrieval practice and keyword mnemonic under conditions in which the dosage of retrieval practice was relatively low (twice per item). Participants studied 40 Lithuanian-English pairs in four different learning conditions reflecting a 2 (with or without keyword) × 2 (with or without retrieval practice) between-subjects factorial design. In the SSS (study-study-study) condition, participants simply studied the list of 40 pairs three times in succession (both keyword and retrieval practice absent). In the STT (study-test-test) condition, after studying the list once, participants retrieved the English meanings given the Lithuanian words during the second and third rounds of the learning phase (keyword absent, retrieval practice present). In the KwKwKw (keyword-keyword-keyword) condition, participants were given instructions about the keyword mnemonic and studied the pairs with suggested keywords and images three times (keyword present, retrieval practice absent). Finally, in the KwTT (keyword-test-test) condition, the participants studied the list once using suggested keywords and imagery, and then they engaged in retrieval practice during the second and the third rounds. The goal of foreign-language vocabulary learning is long-term retention of the vocabulary items’ meanings so that learners can comprehend the vocabulary when it is encountered later. To this end, the current experiments employed relatively long retention intervals (48 h in this first experiment; a week in Experiments 2 and 3).

The three theoretical viewpoints developed in the introduction anticipate different patterns. According to the idea that the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice produce complementary effects, there should be main effects of keyword instruction and of retrieval practice, and these should be additive. The redundancy hypothesis also anticipates main effects of the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice, but predicts that there will be no additional benefit of combining the two techniques (an interaction). Finally, the catalytic hypothesis also anticipates differential effects of testing depending on whether the keyword mnemonic is present. However, the predicted patterns are directly counter to that of the redundancy view: First, no testing effect without the keyword mnemonic is predicted (STT will not differ significantly from SSS) in the context of the current experiment, but a positive benefit is predicted when testing is combined with the keyword mnemonic (KwTT will be better than KwKwKw).

Second, the interaction contrast directly aligning with the catalytic view is that the testing effect in the combined testing-keyword condition (KwTT − KwKwKw) should be significantly more robust than the testing effect without the keyword method (i.e., KwTT − KwKwKw > STT − SSS). The pattern reduces algebraically to the expectation that the contrast (KwTT + SSS) – (KwKwKw + STT) should be significantly greater than zero.Footnote 1 Given the a priori directional prediction, we test this interaction contrast with a one-tailed test throughout.Footnote 2

Method

Design and participants

The experiment was 2 × 2 between-subjects design with the absence or presence of keyword instruction and the absence or presence of retrieval practice (testing) as the independent variables. 120 participants were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (Age: M = 34.13 years, range = 19–66; 74% female, 51% bachelor’s degree or higher) and compensated US$3 for their time. These participants were randomly assigned to the four conditions as follows: SSS (n = 30), STT (n = 29), KwKwKw (n = 30), and KwTT (n= 31). The sample size (n = 30 in each cell) was determined to give us adequate power (≈ .80) to detect medium size main effects and the interaction (f = .30).

Materials

Forty Lithuanian-English word pairs from Grimaldi, Pyc, and Rawson (2010) were used in the current experiment. A keyword and a verbal description of a suggested image were prepared for each word pair and presented in the keyword conditions along with the pairs (visit Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/4gdzm/?view_only=7d96308062b742c89f7f821c52594ac4 for a complete list of word pairs and their keywords). The experiment was programmed in Collector (http://github.com/gikeymarcia/Collector), a PHP-based open-source experiment program designed to run psychological experiments through web-browsers.

Procedure

The experiment consisted of two phases: the learning phase in day 1 and the final test phase in day 2. During the learning phase, all participants went through three rounds of learning 40 Lithuanian-English word pairs. During the first round of the learning phase, all participants were presented with 40 Lithuanian-English pairs one at a time for 10 s in a random order. The participants in the KwKwKw and the KwTT conditions (i.e., the keyword-present conditions) were given a general instruction on the keyword mnemonic initially (i.e., what the keyword mnemonic is and how they should create an image incorporating the keyword and the English meaning) and presented with a suggested keyword and a description of a suggested image along with each word pair. During the subsequent two rounds of learning, the participants in the SSS and the KwKwKw (i.e., the testing-absent conditions) restudied the same 40 pairs in the same method in a new random order. The participants in the STT and the KwTT (i.e., the testing present conditions) were presented with the Lithuanian words one by one and asked to type in their English translation. They were given 7 s to type in their answers, and feedback was provided after each item for 3 s. The participants in the STT condition were given a complete Lithuanian-English pair as feedback while the participants in the KwTT condition were given the keyword and the image that they received in the first round of the learning phase along with each complete word pair. The day 1 procedure took about 30 min to complete.

About 48 h later, the participants completed the final test via a web link sent to their email. All participants were presented with the 40 Lithuanian words one by one in a random order and asked to type in the English translations. They were given as much time as they needed, although all participants completed the final test in less than 15 min. After the final test, participants filled out a demographic questionnaire as well as questions about their usage of the keyword mnemonic during the experiment.

Results

Retrieval success rate during the learning phase

Table 1 shows the retrieval success rates during the learning phase as a function of condition and round. A 2 × 2 mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA), with condition (STT or KwTT) as the between-subjects variable and testing round (first or second) as the within-subjects variable, was conducted on these data. There was a significant main effect of condition, such that the KwTT condition had a greater retrieval success rate over all, F(1, 58) = 7.35, p < .001, ηp2 = .11. The main effect of round of testing was also significant, such that participants’ retrieval success rates were greater in the second than in the first round, F(1, 58) = 97.91, p < .001, ηp2 = .63. The interaction between these two variables was not significant, (F < 1, ηp2 = .010).

Final test performance

Figure 1 shows participants’ mean performances on the final test according to their learning conditions. A 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA was conducted on these data. There was no main effect of testing (F < 1; ηp2 = .008), whereas the main effect of keyword instruction was significant, F(1, 116) = 6.10, p < .05, ηp2 = .050. The interaction was not significant (F < 1, ηp2 = .002). The absence of a testing effect is consistent with the catalytic view; however, additional planned comparisons as described in the introduction are needed to fully evaluate that view. As uniquely anticipated by the catalytic view, testing alone (M = .37, SD = .26) did not enhance learning relative to study alone (M = .35, SD = .27; F < 1, ηp2 =.002). Contrary to the catalytic (and complementary) view, however, testing combined with keyword instruction (M = .51, SD = .21) also did not statistically enhance learning relative to keyword instruction alone (M = .44, SD = .28), F (1, 59) = 1.25, p > .05, ηp2 = .02. Also, though the planned interaction contrast derived from the complementary view was in the anticipated direction, .86 (KwTT + SSS) > .81 (KwKwKw + STT), the difference was not statistically significant (F < 1, p > .05, one-tailed).

Participants’ mean performance on the final test as a function of their condition in Experiment 1. Error bars denote standard error

To provide further statistical support for the conclusion that testing without the keyword mnemonic did not improve performance relative to study alone (SSS vs STT), Bayes factors were calculated (with JASP 0.8.0.0) to assess the strength of evidence in favor of the null effect. The software’s default setting with the Cauchy prior of 0.707 was used to conduct a Bayesian independent samples t-test (Rouder, Speckman, Sun, Morey, & Iverson, 2009) examining the directional hypothesis anticipating a testing effect (i.e., SSS < STT). BF0- was 3.00, which can be interpreted as given the data, the null is three times more likely than the alternative (i.e., a testing effect).

Post-experimental question on spontaneous use of the keyword mnemonic

After the final test, participants in the SSS and the STT conditions (i.e., keyword-absent conditions) were given a general description of what the keyword mnemonic was and asked the following question (participants in the keyword-present conditions were not given this question): “When you learned the Lithuanian-English word pairs a couple of days ago, did you use the ‘keyword mnemonic’?” Out of 59 participants in these conditions, 12 of them indicated no use of the keyword mnemonic (“No, I didn't use it”), 21 of them indicated modest use (“Yes, but for only few of the pairs”), and 26 of them indicated consistent reliance on the keyword mnemonic (“Yes, I used it for all the pairs or as many pairs as possible”). On average, final test performance for the participants who reported not using the keyword mnemonic was .23 (SD = .24), for modest keyword users performance was .44 (SD = .30), and for consistent users performance was .35 (SD = .21). In sum, some participants showed some degree of spontaneous keyword use in the keyword-absent conditions, and this use was associated with somewhat better learning.

Discussion

A main finding, and one consistent with the catalytic but not the complementary or redundancy view, is that retrieval practice alone failed to improve participants’ final test performance relative to study alone. Both the planned contrast and the Bayesian analysis supported this observation. But inconsistent with the catalytic view is that the interaction between the testing and keyword manipulations did not reach significance. The specific planned contrast that directly tested the interaction pattern predicted by the catalytic view also did not reach significance. The upshot was that testing did not produce significant gains in learning either with or without the keyword instruction. Note that none of the views anticipated that testing would consistently fail to significantly enhance learning; thus, the results did not fully support any of the three theoretical views guiding this study.

Nevertheless, one might provisionally argue that the constellation of findings tilts very slightly toward the catalytic view because the data supported one of the catalytic view’s unique predictions: For these materials and limited study and retrieval practice, no testing effect would emerge for the retrieval practice-only condition. By contrast, a testing effect in this condition was predicted by the redundancy and complementary views. Moreover, the planned interaction contrast revealed a positive, albeit nonsignificant, catalytic advantage of combining testing with the keyword mnemonic (a .05 advantage of KwTT + SSS over KwKwKw + STT). Accordingly, we conducted a second experiment to investigate whether these patterns might prove more decisive; that is, we wanted to try to establish the reliability of a testing advantage when retrieval practice is combined with the keyword mnemonic in conjunction with the absence of a testing advantage when the keyword mnemonic is not instructed (again, for contexts in which the retrieval practice dose is relatively low). Alternatively, it remained possible that the second experiment would continue to show the unexpected pattern that limited retrieval practice, even in combination with keyword encoding, does not produce significant gains in foreign vocabulary learning.

Before reporting Experiment 2, we note that many of the participants who were in the keyword-absent conditions self-reported using some sort of keyword mnemonic. Spontaneous use of the keyword mnemonic has been discussed as a potential reason for high performance in a no-instruction control group in an English-vocabulary-learning study conducted at a selective private university (McDaniel & Pressley, 1984). Our results provide evidence for this speculation and extend it by suggesting that this tendency is also prominent in the general population for foreign language vocabulary learning. Yet, the test performance of the modest spontaneous keyword users was numerically higher than that of the consistent users, seemingly contradictory to the final test results observed for participants given instructions to use keywords. Accordingly, in Experiment 2 we more precisely measured the use of keyword-mediated retrieval to better gauge spontaneous keyword use.

Experiment 2

The aim of Experiment 2 was threefold. The first objective was to assess the reliability of the pattern of results that hinted at the catalytic dynamic. A second objective was to examine retention over a longer interval than 2 days (as used in Experiment 1). Thus, in this experiment the retention interval was extended to 1 week. A third objective was to examine different routes through which the meanings of the foreign vocabulary (Lithuanian) words are retrieved. When study explicitly incorporates the keyword mnemonic, later retrieval is presumably mediated by the keywords. However, how successful retrieval is achieved when there is no instruction to use the keyword mnemonic is unclear. One idea is that for arbitrarily paired items, such as a foreign vocabulary item and its English translation, learners may attempt to encode a direct association between the vocabulary word and its meaning for many pairs during initial study (but not necessarily all pairs as discussed above). With this encoding basis, subsequent retrieval must rely on relatively direct retrieval routes (we term this unmediated retrieval) that trace the associative link between the vocabulary word and its meaning (cf. Pyc & Rawson, 2010, 2012, in which learners were instructed to generate mediators during study). The idea of unmediated retrieval in cued recall has received support in past work. For example, Guynn and McDaniel (1999) provided evidence for the notion that explicit retrieval involves accessing target information directly from information encoded at study (see also Jacoby, 1998; Weldon & Colton, 1995).

To investigate the use of different routes (keyword-mediated, unmediated, and others) through which successful retrieval is achieved, we asked retrieval-route questions in the final test phase of Experiment 2. After each response in the final test phase, the participants were asked to describe how they reached their answer. Previous work with learning foreign vocabulary has shown that participants’ self-reports can be sensitive to the retrieval routes they took (Crutcher & Ericsson, 2000). We implemented the retrieval-route questions in order to: (1) gauge the frequency with which unmediated and keyword-mediated retrieval took place across the keyword-present and keyword-absent conditions, and (2) examine whether the accuracy of these retrieval-route types differed. On the one hand, the unmediated retrieval could be as effective as the keyword-mediated retrieval; each could simply reflect different routes through which successful retrieval is achieved. On the other hand, the keyword-mediated retrieval could be more effective than the unmediated retrieval because the retrieval process is guided by a strong mediator that provides effective cuing (see, e.g., Pyc & Rawson, 2012) or favorably constrains retrieval (Thomas & McDaniel, 2013).

Method

Participants

Ninety-four undergraduates (24 in SSS, 25 in STT, 23 in KwKwKw, and 22 in KwTT; Age: M = 19.13 years, range = 19–21; 59% female) from Washington University in St. Louis participated in the study as a part of a course requirement or US$10. We thought that around 25 participants per cell would be adequate on the assumption that the testing effect becomes more robust as the delay gets longer, when found (Roediger & Karpicke, );Footnote 3 the determined sample size provided high power (> .90) to detect an anticipated large effect (f = .40).

Design and materials

The design and materials were identical to Experiment 1.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to Experiment 1 except for three differences. First, the experiment was conducted in the laboratory as opposed to online. Second, Experiment 2 employed a 1-week delay instead of a 48-h delay as in Experiment 1. Third, after answering each item in the final testing phase, the participants answered the following retrieval-route question: “Please describe how you reached the previous answer (your thought process) in as much detail as possible. Did the English translation directly come to mind when you saw the Lithuanian word or did anything else come to mind before reaching the English translation? (if you left the previous answer blank, simply skip this question).”

Results and discussion

Retrieval success rate during the learning phase

Table 2 shows the retrieval success rates during the learning phase as a function of condition and round. A 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA, with condition (STT or KwTT) as the between-subjects variable and testing round (first or second) as the within-subjects variable, was conducted on these data. There was a significant main effect of condition, such that the KwTT condition had a greater retrieval success rate over all, F(1, 45) = 14.45, p < .001, ηp2 = .24. The main effect of round of testing was also significant, such that participants’ retrieval success rates were greater in the second than in the first round, F(1, 45) = 172.10, p < .001, ηp2 = .79. The interaction between these two variables was not significant (F < 1, ηp2 = .016).

Final test performance

Figure 2 shows participants’ mean performance on the final test according to their conditions. A 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA was conducted on these data. There was a significant main effect of testing, such that the testing-present conditions outperformed the testing-absent conditions, F(1, 90) = 4.90, p < .05, ηp2 = .052. There was also a significant main effect of providing keywords, such that the keyword-present conditions outperformed the keyword-absent conditions, F(1, 90) = 23.16, p < .001, ηp2 = .21. However, these main effects were qualified by a significant interaction, F(1, 90) = 5.65, p < .05, ηp2 = .059. Planned comparisons showed that, as predicted by the catalytic view, testing did not enhance recall when the keywords were absent (SSS vs STT), F(1, 47) < 1, p > .05, ηp2 = .00, but it did when the keywords were present (KwKwKw vs KwTT), F(1, 43) = 8.21, p < .01, ηp2 = .16. The planned contrast testing the unique interaction pattern predicted by the catalytic view (i.e., KwTT + SSS > KwKwKw + STT) revealed that KwTT + SSS (.74) was indeed significantly better than KwKwKw + STT (.54), F(1, 90) = 5.65, p < .01Footnote 4 (one-tailed). Thus, counter to the redundancy (and complementary) view, combining the keyword mnemonic with testing produced better performance than the sum of each effect alone.

Participants’ mean performance on the final test as a function of their condition in Experiment 2. Error bars denote standard error

We again conducted a Bayesian independent samples t-test to assess the strength of evidence in favor of the null effect of testing relative to study alone (SSS vs. STT). The parameters were identical to the analysis in Experiment 1 with the Cauchy prior of 0.707 and examination of the directional hypothesis (i.e., SSS < STT). BF0- was 3.85, which can be interpreted as given the data, the null is 3.85 times more likely than the alternative (i.e., a testing effect), providing moderate evidence in favor of the null effect.

Frequency of retrieval-route types

The participants’ responses on the retrieval-route questions were coded into three discrete categories: Unmediated retrieval, keyword-mediated retrieval, and other types of mediation (referred to hereafter as othersFootnote 6). Initially, two raters scored 200 responses from five participants, and the Cohen’s kappa coefficient (k) was .94. Based on the high inter-rater reliability, one rater coded the rest of the data. All 45 participants in the keyword-present conditions (i.e., KwKwKw and KwTT) attributed at least one of their answers to keyword-mediated retrieval, whereas 42 out of the 49 participants in the keyword-absent conditions (i.e., SSS and STT) did so. Figure 3 shows the proportions of the three retrieval-route types in each condition. As expected, the vast majority of responses from the keyword-present conditions were keyword-mediated. Somewhat surprisingly, there was not only a mixture of the three retrieval-route types in the keyword-absent conditions, but there was a numerically greater number of keyword-mediated responses than unmediated responses in these conditions.

Proportion of participants’ retrieval route types as indicated in the retrieval-route questions during the final test phase in Experiment 2. Error bars denote ± 1 standard error

The accuracy of each retrieval-route type

In 3,754 test trials given to 94 participants,Footnote 7 1,817 responses were recorded, of which 1,246 were keyword-mediated, 373 were unmediated, and 198 were others. The keyword-mediated responses had a probability of 71% being correct while that of the unmediated responses and others responses were 51% and 56%, respectively.

To examine the relative accuracy of each retrieval-route type more formally, binary logistic regression analyses were conducted. Because the retrieval route for the trials left blank is unidentified, only the 1,817 responses (final test trials for which an answer was provided) were included in these analyses. A summary of these analyses is shown in Table 3. We constructed three separate models entering each of the three retrieval-route types as the predictor and the outcome of a given final test response (i.e., correct or incorrect) as the dependent variable. The main statistics of interest here are the odds ratios (OR: the exponentiation of B). ORs are calculated by dividing the odds of successful recall (i.e., the probability of successful recall divided by one minus the probability of successful recall) when the predictor is present by the odds of successful recall when the predictor is absent. In our case, because all 1,817 responses were coded keyword-mediated, unmediated, or others, it is the factor with which the odds of successful recall increases (or decreases) when one type of retrieval route was reported compared to when other retrieval routes were reported. For example, the OR of 2.14 in the model with the keyword-mediated retrieval as the predictor (Model 1) indicates that the odds of successful recall are 2.14 times greater when keyword-mediated retrieval was reported compared to when other retrieval routes were reported, p < .001, 95% CI = [1.74, 2.63]. Overall, these models clearly showed the superiority of the keyword-mediated retrieval over other retrieval routes. Taking these results and the frequency data reported above together, KwTT’s advantage relative to the ineffectiveness of STT is characterized by its reliance on the more effective keyword-mediated retrieval.

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 had two primary purposes. First, we attempted to establish the reliability of the key pattern from Experiment 2 – the testing by keyword interaction, such that testing improved final performance only when combined with keyword encoding. Second, we wanted to determine whether the catalytic dynamics observed in the previous experiments are indeed limited to low testing dosages. To this end, we included conditions in which participants practiced each pair four times (i.e., SSSSS, STTTT, KwKwKwKwKw, and KwTTTT) in addition to conditions in which each pair was practiced twice (as in Experiments 1 and 2). Because we were interested in whether the catalytic interaction pattern and the testing effect manifest in two distinctive situations (i.e., two-time and four-time testing conditions), not in these conditions combined together, we analyze these conditions separately to directly assess our predictions. The critical test in which we were most interested is the planned comparison testing the unique interaction pattern predicted by the catalytic view, and we conduct this comparison for the two-time and four-time testing conditions separately (i.e., KwTT + SSS > KwKwKw + STT in the two-time and KwTTTT + SSSSS > KwKwKwKwKw + STTTT in the four-time condition). If the catalytic dynamic in the low-testing-dose situation observed in Experiment 2 is reliable, KwTT + SSS should be significantly better than KwKwKw + STT in the two-time-testing conditions. Whether the catalytic dynamic will emerge in the four-dose condition is unclear. On the one hand, it seems possible that the benefit of testing can be boosted by keywords even if testing is effective on its own (with a four-test dose; e.g., Kang & Pashler, 2014); if so, then the planned interaction comparison should be significant. On the other hand, it is possible that the catalytic dynamic is limited to low-testing-dose situations where testing is not effective on its own; if so, then there should be no significant interaction comparison. That is, simple additive effects of the keyword mnemonic and testing would be expected, as predicted by the complementary view.

Method

Participants

Two-hundred and thirty-three participants (30 in SSS, 29 in STT, 26 in KwKwKw, 31 in KwTT, 29 in SSSSS, 30 in STTTT, 31 in KwKwKwKwKw, 27 in KwTTTT; Age: M =36.78 years, range = 21–73; 60% female, 52% bachelor’s degree or higher) participated in the experiment through Amazon Mechanical Turk. They were compensated US$6 for their time. The sample size (n ≈ 30 in each cell) was determined to give us high power (> .90) to detect both medium size main effects (f = .30) and medium size interactions (f = .30).

Design

A 2 × 2 × 2 between-subjects factorial design was employed, with the presence of the keyword instruction, the presence of retrieval practice, and the amount of practice (two-time or four-time) as the independent variables.

Materials

The materials were identical to Experiments 1 and 2.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to Experiment 2 except that the four-time-practice conditions had two additional rounds of practice.

Results and discussion

Retrieval success rate during the learning phase

Table 4 shows the retrieval success rates during the learning phase as a function of condition and round. Because the two-time and four-time-practice conditions had different numbers of testing rounds, they were analyzed in separate ANOVAs. A 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA was conducted for the two-time-practice conditions, with condition (STT or KwTT) as the between-subjects variable and testing round (first or second) as the within-subjects variable. The main effect of condition did not reach significance, although the KwTT condition had a numerical advantage overall (STT: M = .29, SD = .20; KwTT: M = .37, SD = .21), F(1, 58) = 2.35, p = .13, ηp2 = .04. The main effect of round of testing was significant, such that participants’ retrieval success rates were greater in the second than in the first round, F(1, 58) = 183.16, p < .001, ηp2 = .76. The interaction between these two variables was not significant, F = 1.42, p > .05, ηp2 = .016.

A 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA was conducted for the four-time-practice conditions, with condition (STTTT or KwTTTT) as the between-subjects variable and testing round (first, second, third, or fourth) as the within-subjects variable. There was a significant main effect of condition, such that the KwTTTT condition had a greater retrieval success rate overall(STTTT: M = .36, SD = .24; KwTTTT: M = .51, SD = .24), F(1, 55) = 5.65, p < .05, ηp2 = .09. The main effect of round of testing was also significant, such that participants’ retrieval success rates improved as the testing rounds went further, F(1, 55) = 111.41, p < .001, ηp2 = .67. The interaction between these two variables was not significant (F < 1, ηp2 = .001).

Final test performance

Figure 4 shows participants’ mean performance on the final test according to their conditions. To directly examine the expectations outlined in the introduction, we conducted separate 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVAs for the two-time and four-time practice conditions. For the two-time-practice conditions, there was a marginally significant effect of testing, with the testing-present conditions showing an advantage relative to the testing-absent conditions, F(1, 112) = 3.64, p = .059, ηp2 = .03. The main effect of providing keywords was significant, such that the keyword-present conditions outperformed the keyword-absent conditions, F(1, 112) = 12.06, p < .01, ηp2 = .10. The interaction between keyword (presence, absence) and testing (presence, absence) was also marginally significant, F(1, 112) = 2.79, p = .098, ηp2 = .02. In line with the catalytic view, the two practice-doses testing did not enhance recall when the keywords were absent (SSS vs STT), F(1, 57) < 1, p > .05, ηp2 = .00, but it did when the keywords were present (KwKwKw vs KwTT), F(1, 55) = 4.55, p < .05, ηp2 = .08. In addition, the planned contrast examining the interaction pattern predicted by the catalytic view (i.e., KwTT + SSS > KwKwKw + STT) revealed that KwTT + SSS (.70) was significantly better than KwKwKw + STT (.50), F(1, 112) = 2.77, p < .05 (one-tailed).

Participants’ mean performance on the final test as a function of their condition in Experiment 3. Error bars denote standard error

For the four-practice conditions, there was a significant main effect of testing, such that the testing-present conditions showed an advantage relative to the testing-absent conditions, F(1, 113) = 10.50, p < .01, ηp2 = .09, as well as a significant main effect of providing keywords, with the keyword-present conditions showing an advantage relative to the keyword-absent conditions, F(1, 113) = 5.76, p < .05, ηp2 = .05. In contrast to the two-practice conditions, with four-time practice there was no hint of an interaction between the keyword and testing conditions, F(1, 113) < 1, p > .05, ηp2 = .01. The planned contrast examining the interaction pattern predicted by the catalytic view (i.e., KwTT + SSS > KwKwKw + STT) corroborated this finding, such that KwTTTT + SSSSS (.79) was not significantly better than KwKwKwKwKw + STTTT (.70) in the four-practice condition, F < 1, p > .05 (one-tailed).

We again conducted a Bayesian independent samples t-test to assess the strength of evidence in favor of the null effect of testing relative to study alone (SSS vs STT) in the two-time-practice conditions. The parameters were identical to the analyses in Experiments 1 and 2 with the Cauchy prior of 0.707 and examination of the directional hypothesis (i.e., SSS < STT). BF0- was 2.06, which can be interpreted as given the data, the null is 2.06 times more likely than the alternative (i.e., a testing effect), providing anecdotal evidence in favor of the null effect (Wagenmakers et al., 2018).

In addition, to address the possibility that the SSS-STT comparison did not yield a statistically significant testing effect in Experiments 1, 2, and 3 individually because each lacked adequate power to detect the effect, we combined and analyzed the data from these two conditions from the three experiments. Final recall across these two conditions (SSS: M = .26, SD = .22; STT M = .27, SD = .21) was virtually equivalent, t(158) = 0.39, p > .05, d =.06. Further, a Bayesian independent-sample t-test with the same parameter described above showed that BF0- was 4.24, which can be interpreted as given the data, the null is 4.24 times more likely than the alternative (i.e., a testing effect), providing moderate evidence in favor of the null effect.

Similarly, to examine the critical two-way interaction between testing and the keyword mnemonic with the highest possible power, we combined and analyzed the recall data from the two-time-practive conditions in Experiments 1, 2, and 3 with a 2 × 2 × 3 between-subjects ANOVA (presence or absence of testing, presence or absence of keywords, and experiment number). This interaction between testing and the keyword mnemonic was significant, F(1, 318) = 6.30, p < .05, ηp2 = .019. We also conducted the planned contrast examining the catalytic interaction pattern (i.e., KwTT + SSS > KwKwKw + STT) on the combined data from Experiments 1, 2, and 3 (using the two-time-practice conditions from Experiment 3). This analysis confirmed that KwTT + SSS (.72) was statistically significantly better than KwKwKw + STT (.62) as predicted by the catalytic view, F(1, 318) = 5.55, p < .01 (one-tailed).

In sum, Experiment 3 outcomes largely replicated the catalytic effects observed in Experiment 2; in the two-time-practice conditions, testing was only effective when the keyword mnemonic was involved. This interaction between testing and the keyword mnemonic was not significant in the four-time-practice conditions, the conditions in which test-enhanced learning has been observed in previous vocabulary-learning experiments (e.g., Kang & Pashler, 2014) and approached significance in the current experiment (SSSSS: .27 vs STTTT: .37, p = .095, d = .44). That is, the benefits of testing and the keyword mnemonic were additive when a testing effect began to emerge (four-time practice), but the keyword mnemonic catalyzed a testing effect when testing alone was not effective (two-time practice). This observation is further reinforced by the significant planned contrast (testing the specific interaction pattern predicted by the catalytic view) in the two-time-practice but not in the four-time-practice conditions. Moreover, the Bayesian analysis combining the data from all three experiments showed that when there are only two practice opportunities, it is more than four times likely that there is no difference between SSS and STT conditions than that the true mean of STT is higher than SSS. Lastly, the examination of the critical testing by keyword mnemonic interaction anticipated by the catalytic hypothesis when combining data from all three experiments confirmed that the interaction was statistically reliable and did not significantly change across the three experiments (F < 1, for the three-way interaction). Most telling, the planned interaction contrast (aligned with the catalytic view) combining the data from three experiments was also statistically reliable.

Frequency of retrieval-route types

Just as in Experiment 2, the participants’ responses on the retrieval-route questions were coded into three discrete categories: Unmediated retrieval, keyword-mediated retrieval, and others. One of the two raters from Experiment 2 scored all responses. Data from 11 participants were excluded from these analyses because they left all the retrieval-route questions blank, left nonsensical responses for all of them, or misunderstood the question as confidence judgment or speed judgment (how quickly the answer came to mind). Figure 5 shows the proportions of the three retrieval-route types in each condition. These data generally follow the pattern observed in Experiment 2; the responses in the keyword-present conditions were dominated by keyword-mediated retrieval and the responses in the keyword-absent conditions were a mix of three retrieval-route types.

Proportion of participants’ retrieval route types as indicated in the retrieval-route questions during the final test phase in Experiment 3. Error bars denote ± 1 standard error

The accuracy of each retrieval-route type

In 8,880 test trials given to 222 participants, 4,588 responses were recorded, of which 2,466 of them were keyword-mediated, 1,155 of them were unmediated, and 967 of them were others. The keyword-mediated responses had a probability of 77% being correct, while that of the unmediated responses and others responses were 55% and 33%, respectively.

As in Experiment 2, binary logistic regression analyses including only the 4,588 responses (final test trials for which an answer was provided) were conducted to examine the relative accuracy of each retrieval-route type. A summary of these analyses is shown in Table 5. We again constructed three separate models entering each of the three retrieval-route types as the predictor and the outcome of a given final test response (i.e., correct or incorrect) as the dependent variable (Models 1–3). The results largely replicated the analyses in Experiment 2 in that the model using the keyword-mediated retrieval as a predictor had a significantly greater odds ratio than the models using the unmediated and other retrieval routes as predictors, once again showing the superiority of the keyword-mediated retrieval over other retrieval types.

General discussion

In three experiments, we examined the efficacy of the combination of the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice in learning Lithuanian-English word pairs. All experiments showed that two trials of retrieval practice alone did not enhance learning relative to study (SSS vs STT). This relatively novel absence of a testing effect was supported by the analyses combining the SSS and STT conditions from all three experiments; final performance in SSS was virtually the same as in STT and, accordingly, the testing effect was not close to being significant based on standard inferential statistics. Moreover, the null (i.e., no testing effect) was more than four times likely than the directional hypothesis anticipated by testing effect (i.e., SSS < STT) according to the Bayesian analysis. In addition, the keyword-retrieval combination produced better performance than keyword alone, as demonstrated in the numerical advantage in Experiment 1 as well as the significant advantage in Experiment 2 and in the two-time-testing conditions of Experiment 3. These results thus disfavor the theoretical view that the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice might produce positive but redundant effects, so that combining the two would produce little enhancement in learning (the redundancy view).

A perhaps more attractive theoretical view developed at the outset was that the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice would have additive effects, with the keyword mnemonic enriching encoding and retrieval practice enhancing retrieval processes (the complementary view). However, the superiority of the keyword-retrieval combination was not due to additive benefits of the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice. Instead, retrieval practice interacted with the keyword mnemonic manipulation (absence, presence), such that retrieval practice was effective only when combined with the keyword mnemonic (Experiment 2; Experiment 3 for the two-practice round conditions). Specifically, counter to the assumption of the complementary view, in the present learning context, as just noted, two rounds of retrieval practice alone consistently did not benefit learning relative to repeated study (Experiments 1, 2, and 3).

The obtained results are most consistent with the catalytic view outlined in the introduction. This view anticipated the superiority of the keyword-retrieval combination not through an addition of the benefits of the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice but through an interaction of the two techniques. The core idea of this view is that testing alone may not be effective for enhancing learning of foreign language-meaning associations because these associations are entirely arbitrary. In the absence of a semantic relationship between the cue (foreign vocabulary item) and the target (the item’s meaning), with one study opportunity and a limited number of practice testing rounds, the presumed semantic enhancement of retrieval practice may be obviated (e.g., encoding variability – McDaniel & Masson, 1985; mediator shift – Pyc & Rawson, 2012; semantic elaboration – Kang, 2010). Benefits of retrieval practice were catalyzed when the keyword mnemonic was implemented at initial study presumably because the keyword mnemonic provides a fruitful retrieval route that can be solidified with subsequent retrieval practice.

As just mentioned, a key finding that characterizes the catalytic dynamic is the observation that two rounds of retrieval practice after initial studying did not enhance foreign-language vocabulary learning. This absence of a testing effect contrasts with effects observed with other types of materials, such as of text passages, in which one test after initial studying produces test-enhanced learning (e.g., Roediger & Karpicke). The discrepancy in the effects of retrieval practice with foreign language vocabulary (the absence of an effect as reported herein) and other materials likely is a consequence of the arbitrary nature of the association between vocabulary items and their meaning. Materials for which testing effects are typically observed after one retrieval practice offer pre-existing semantic relationships to be magnified between a cue and a target (e.g., for materials like English-English pairs) or among propositions in a text passage. Accordingly, the semantically-oriented elaboration mechanisms that are posited to underlie the memorial benefits of testing (e.g., McDaniel & Masson, 1985; Pyc & Rawson, 2010; Roediger & Butler, 2011) are functional with such materials but apparently not immediately fruitful with semantically impoverished items (like foreign vocabulary words). As suggested in the current Experiment 3 and the extant literature (e.g., Jönsson et al., 2014; Kang & Pashler, 2014; Karpicke, 2009), benefiting learning in foreign language vocabulary learning through testing alone may require more extensive testing sessions or extensive study before testing because forging a relationship between a vocabulary item and its meaning (e.g., developing effective mediators) is challenging and takes time.

It is important to note that there is nothing special about two practice times as the number that produces the situation in which the catalytic dynamics can be observed (i.e., testing alone does not enhance learning). Factors, such as the number of pairs to be learned, the presentation duration of each learning trial, and the delay between each retrieval practice trial, would likely affect the amount of retrieval practice needed for the testing effect to emerge. For example, if the number of pairs to be learned in the current experiments was 20 instead of 40, we might have observed test-enhanced learning with only two times of retrieval practice. Clearly, the catalytic hypothesis cannot at this point specify the precise list-length, study-time, and spacing parameters under which retrieval practice might generally be potent (and we are not aware of any current theory that can do so); however, the catalytic hypothesis is valuable in suggesting that when there are too few retrieval practice opportunities to enhance later recall by testing alone, the memorial benefit of testing can be brought forward by combining the keyword mnemonic or other mnemonic encoding with the limited retrieval practice opportunities that are available. More specifically, the present theoretical position (catalytic view) cautions that the effectiveness of retrieval practice alone, with a limited dose of retrieval practice, might be restricted when the nature of the material does not support a semantic association between the to-be-learned components. Examples of such materials could include face-name pairs (e.g., Landauer & Bjork, 1978; Maddox & Balota, 2012), biological taxonomies (e.g., Levin & Levin, 1990), and arbitrary pairings of geographical areas and names (e.g., Rohrer, Taylor, & Sholar, 2010). This caution is an important consideration often neglected by researchers and educators in light of the generally robust testing effects reported in the literature (e.g., Dunlosky et al., 2013; Rowland, 2014). In these instances, the present theoretical and empirical outcomes suggest that combining testing with a mnemonic encoding strategy could effectively boost the potency of testing to support memory performance. This suggestion awaits further research.

In the instances when testing is effective on its own, our results (Experiment 3) suggest that combining testing with the keyword mnemonic may have complementary effects: In the four-dose condition in Experiment 3, the effects of testing and keyword mnemonic were additive (see also Morris et al., 2005). When considering the more general issue of whether combining an additional encoding activity to testing (when testing alone benefits learning) will be complementary or redundant with testing, a theoretical analysis of testing effects in terms of individual-item and relational processing (cf. multifactor account: Hunt & McDaniel, 1993; see also McDaniel, Moore, & Whiteman, 1998) might prove valuable. Testing has been shown to elicit both individual-item processing (i.e., processing that strengthens the memory of a given item; e.g., Mulligan & Peterson, 2015) as well as relational processing (i.e., processing that strengthens the relationship with other items in a set; e.g., Masson & McDaniel, 1981; Zaromb & Roediger, 2010). Relevant to the present issue, the type of processing that is enhanced through testing depends on the situation. For instance, Peterson and Mulligan (2013; see also Mulligan & Peterson, 2015) showed that in learning words from several categories paired with rhyming cues (e.g., Force-Horse and Swear-Bear from the animal category, Tape-Grape and Teach-Peach from the fruit category), testing using a rhyming cue (e.g., Force-???; Tape-???) enhanced the cue-target association (i.e., individual-item processing at the pair level) at the expense of processing based on the category membership (i.e., relational processing). Applied to this particular paradigm, the redundancy hypothesis suggests that combining an individual-item encoding manipulation (e.g., rating the pleasantness of the pairs) with testing would not change final performance over the effects of each alone. In contrast, the complementary hypothesis suggests that combining a relational encoding manipulation (e.g., a categorical processing task) would enhance recall through providing processing complementary to the individual-item processing elicited by testing. By the same token, in paradigms in which testing primarily promotes relational processing (e.g., Masson & McDaniel, 1981), combining testing with a relational encoding task would be expected to show redundancy effects, whereas combining testing with an individual-item encoding task would be expected to show complementary effects. These possibilities are intended as illustrative of how the redundancy and complementary hypotheses for testing effect – encoding combinations could be manifested; clearly further empirical exploration is needed.

Feedback at retrieval practice and the catalytic dynamics

The present findings suggest that in addition to benefits of keyword encoding per se, the keyword-mnemonic provides a second benefit, that of catalyzing the effectiveness of retrieval practice that students might engage (e.g., when using flashcards; Miyatsu, Nguyen, & McDaniel, 2018). Some might wonder if this effect was partly due to the feedback provided during retrieval practice, especially considering that the feedback in the current experiments contained both the correct answer and the suggested keywords in the KwTT condition. Evidence suggests that retrieval practice attempts enhance memory regardless of retrieval success when feedback is given (see Kornell & Vaughn, 2016, for review), and in the current paradigm perhaps the feedback on failed retrieval attempts enhanced learning more so for the keyword-encoding condition than the no-keyword condition. However, the lack of significant interaction in all experiments between condition (STT vs KwTT) and testing round suggests that the effect of feedback did not differ between the STT and the KwTT conditions. Moreover, the initial retrieval practice data suggest that the catalytic effect should also be present when no feedback is given during retrieval practice. As evident from the retrieval success rates during the first round of retrieval practice in the current experiments, the keyword instruction substantially increased the retrieval success rates. If feedback had not been provided, the memorial benefits of retrieval practice would very likely be limited to the items that were successfully retrieved (e.g., Bjork, 1988; Carrier & Pashler, 1992; Kuo & Hirshman, 1996; McDaniel & Masson, 1985; Runquist, 1983). Accordingly, it seems plausible then that without feedback, the keyword instruction advantage observed in the initial retrieval success rates would be subsequently reflected in the final test performance difference between the KwTT and STT conditions, thereby showing the catalytic effect. More generally speaking, these findings emphasize the importance of incorporating strong encoding techniques, the keyword mnemonic or otherwise, regardless of whether retrieval is accompanied by feedback.

Concluding comments

In three experiments, we examined the efficacy of combining the keyword mnemonic with retrieval practice. The benefit of combining the keyword mnemonic with retrieval practice was evident at 48-h and 1-week final-test delays. In addition to the theoretical implications discussed above, our findings have practical value. Specifically, the findings suggest that under vocabulary-learning circumstances in which only a relatively modest amount of retrieval practice is engaged, retrieval practice is best combined with some other mnemonic support. Further, the Experiment 3 results suggest that even when the amount of retrieval practice is extended (to four retrieval practices) so that test-enhanced learning begins to emerge, incorporating other mnemonic support adds to the effect of retrieval practice. This recommendation represents an advance over previous general recommendations regarding the general utility of retrieval practice (e.g., Dunlosky et al., 2013). Accordingly, researchers might start examining the efficacy of combining various mnemonic techniques with retrieval practice. We do not claim that the keyword mnemonic and retrieval practice have a special chemistry together. Rather, our view is that many other mnemonic encoding techniques might augment the benefits of retrieval practice. Identifying potent combinations of enriched (mnemonic) encoding and retrieval practice would support more precise recommendations for educators and students (see Miyatsu et al., 2018, for a related discussion), as well as further understanding of how retrieval practice benefits memory and learning.

Notes

This contrast will be tested throughout the paper by giving a weight of 1, -1, -1, and 1 to SSS, STT, KwKwKw, and KwTT conditions, respectively (see Kirk, 1983, for details).

It is important to emphasize that this directional interaction contrast is more specific to the pattern anticipated by the catalytic view, whereas the interaction test in the omnibus ANOVA also tests other patterns, such as a cross-over interaction wherein testing is effective on its own but with keyword no testing is better than testing. This particular interaction pattern would be tested using a different contrast with a weight of -1, 1, 1, and -1 to SSS, STT, KwKwKw, and KwTT conditions, respectively (see Abelson & Prentice, 1997 for different methods of interaction contrasts).

We overlooked that although this is true when the delay increases from a few minutes to several hours or a couple of days, there is no evidence suggesting that the testing effect is larger at a 1-week delay than at a 48-h delay. We thank a previous reader of the article for pointing this out.

We converted the F-value to a t-value (F = t2) to calculate the one-tailed p-value.

For additional analysis concerning types of errors made and retrieval-route type, see Supplementary Materials.

The vast majority of the responses coded as others were either phonetic (e.g., “I remembered that the English translation rhymed with this word) or orthographic (“I remembered that the English translation and this word started from the same letter”) in nature.

Of 3,760 total test trials (i.e., 40 trials from each of the 94 participants), six trials were lost due to a computer program malfunction.

References

Abelson, R. P., & Prentice, D. A. (1997). Contrast tests of interaction hypothesis. Psychological Methods, 2(4), 315.

Atkinson, R.C. (1975). Mnemotechnics in second-language learning. American Psychologist 30(8), 821–28.

Atkinson, R. C. & Raugh, M. R. (1975). An application of the mnemonic keyword mnemonic to the acquisition of a Russian vocabulary. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 1(2), 126–33.

Bellezza, F. S. (1987). Mnemonic devices and memory schemas. In M A McDaniel & M Pressley (Eds), Imagery and related mnemonic devices: Theories, individual differences, and applications (pp. 34-55). New York: Springer-Verlag

Bjork, R. A. (1988). Retrieval practice and the maintenance of the knowledge. In M. M. Glenberg, P. E. Morris, & R. N. Sykes (Eds.), Practical aspects of memory (pp. 397-401). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1992). A new theory of disuse and an old theory of stimulus fluctuation. From learning processes to cognitive processes: Essays in honor of William K. Estes, 2, 35–67.

Carlson, R. F., Kincaid, J. P., Lance, S., & Hodgson, T. (1976). Spontaneous use of mnemonics and grade point average. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 92(1), 117–122.

Carpenter, S. K., Pashler, H., Wixted, J. T., & Vul, E. (2008). The effects of tests on learning and forgetting. Memory & Cognition, 36(2), 438-448.

Carrier, M., & Pashler, H. (1992). The influence of retrieval on retention. Memory & Cognition, 20(6), 633-642.

Crutcher, R. J., & Ericsson, K. A. (2000). The role of mediators in memory retrieval as a function of practice: Controlled mediation to direct access. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26(5), 1297.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58.

Fritz, C. O., Morris, P. E., Acton, M., Voelkel, A. R., & Etkind, R. (2007). Comparing and combining retrieval practice and the keyword mnemonic for foreign vocabulary learning. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21(4), 499-526.

Gipe, J. P. (1978). Investigating techniques for teaching word meanings. Reading Research Quarterly, 14(4), 624-644.

Grimaldi, P. J., Pyc, M. A., & Rawson, K. A. (2010). Normative multitrial recall performance, metacognitive judgments, and retrieval latencies for Lithuanian—English paired associates. Behavior Research Mnemonics, 42(3), 634-642.

Guynn, M. J., & McDaniel, M. A. (1999). Generate–Sometimes recognize, sometimes not. Journal of Memory and Language, 41(3), 398-415.

Hunt, R. R., & McDaniel, M. A. (1993). The enigma of organization and distinctiveness. Journal of Memory and Language, 32(4), 421-445.

Jacoby, L. L. (1998). Invariance in automatic influences of memory: Toward a user's guide for the process-dissociation procedure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 24(1), 3.

Jacoby, L. L., & Hollingshead, A. (1990). Toward a generate/recognize model of performance on direct and indirect tests of memory. Journal of Memory and Language, 29(4), 433-454.

Jönsson, F. U., Kubik, V., Sundqvist, M. L., Todorov, I., & Jonsson, B. (2014). How crucial is the response format for the testing effect? Psychological Research, 78(5), 623-633.

Kang, S. H. (2010). Enhancing visuospatial learning: The benefit of retrieval practice. Memory & Cognition, 38(8), 1009-1017.

Kang, S. H., & Pashler, H. (2014). Is the benefit of retrieval practice modulated by motivation? Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3(3), 183-188.

Karpicke, J. D. (2009). Metacognitive control and strategy selection: Deciding to practice retrieval during learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 138(4), 469.

Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science, 319(5865), 966-968.

Karpicke, J. D., & Smith, M. A. (2012). Separate mnemonic effects of retrieval practice and elaborative encoding. Journal of Memory and Language, 67(1), 17-29.

Keresztes, A., Kaiser, D., Kovács, G., & Racsmány, M. (2014). Testing promotes long-term learning via stabilizing activation patterns in a large network of brain areas. Cerebral Cortex, 24(11), 3025-3035.

Kornell, N., & Vaughn, K. E. (2016). How retrieval attempts affect learning: A review and synthesis. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation (Vol. 65, pp. 183-215). Academic Press.

Kuo, T. M., & Hirshman, E. (1996). Investigations of the testing effect. The American Journal of Psychology, 109(3), 451-464.

Landauer, T. K., & Bjork, R. A. (1978). Optimum rehearsal patterns and name learning. In M. Gruneberg, P. E. Morris, & R. N. Sykes (Eds.), Practical aspects of memory (pp. 625-632). London: Academic Press.

Levin, M. E., & Levin, J. R. (1990). Scientific mnemonomies: Methods for maximizing more than memory. American Educational Research Journal, 27(2), 301-321.

Maddox, G. B., & Balota, D. A. (2012). Self control of when and how much to test face–name pairs in a novel spaced retrieval paradigm: An examination of age-related differences. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 19(5), 620-643.

Masson, M. E., & McDaniel, M. A. (1981). The role of organizational processes in long-term retention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 7(2), 100.

McCabe, J. A., Osha, K. L., Roche, J. A., & Susser, J. A. (2013). Psychology students’ knowledge and use of mnemonics. Teaching of Psychology, 40(3), 183–192.

McDaniel, M. A., Einstein, G. O., & Lollis, T. (1988). Qualitative and quantitative considerations in encoding difficulty effects. Memory & Cognition, 16(1), 8-14.

McDaniel, M. A., & Masson, M. E. (1985). Altering memory representations through retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 11(2), 371.

McDaniel, M. A., Moore, B., & Whiteman, H. (1998). Dynamic changes in hypermnesia across early and late tests: A relational/item-specific account. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 24(1), 173-185.

McDaniel, M. A., & Pressley, M. (1984). Putting the keyword mnemonic in context. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(4), 598.

McDaniel, M. A., & Pressley, M. (1989). Keyword and context instruction of new vocabulary meanings: Effects on text comprehension and memory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(2), 204.