Published online Aug 21, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i31.4534

Peer-review started: March 26, 2019

First decision: April 11, 2019

Revised: May 28, 2019

Accepted: July 19, 2019

Article in press: July 19, 2019

Published online: August 21, 2019

Crohn’s disease (CD) can affect the entire gastrointestinal tract. Proximal small bowel (SB) lesions are associated with a significant risk of stricturing disease and multiple abdominal surgeries. The assessment of SB in patients with CD is therefore necessary because it may have a significant impact on prognosis with potential therapeutic implications. Because of the weak correlation that exists between symptoms and endoscopic disease activity, the “treat-to-target” paradigm has been developed, and the associated treatment goal is to achieve and maintain deep remission, encompassing both clinical and endoscopic remission. Small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) allows to visualize the mucosal surface of the entire SB. At that time, there is no recommendation regarding the use of SBCE during follow-up.

To investigate the impact of SBCE in a treat-to-target strategy in patients with CD.

An electronic literature search was conducted in PubMed and Cochrane library using the following search terms: “capsule endoscopy”, in combination with “Crohn’s disease” and “treat-to-target” or synonyms. Two authors independently reviewed titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy after duplicates were removed. Following the initial screening of abstracts, all articles containing information about SBCE in the context of treat-to-target strategy in patients with CD were included. Full-text articles were retrieved, reference lists were screened manually to identify additional studies.

Forty-seven articles were included in this review. Two indexes are currently used to quantify disease activity using SBCE, and there is good correlation between them. SBCE was shown to be useful for disease reclassification in patients who are suspected of having or who are diagnosed with CD, with a significant incremental diagnostic yield compared to other diagnostic modalities. Nine studies also demonstrated that the mucosal healing can be evaluated by SBCE to monitor the effect of medical treatment in patients with CD. This review also demonstrated that SBCE can detect post-operative recurrence to a similar extent as ileocolonoscopy, and proximal SB lesions that are beyond the reach of the colonoscope in over half of the patients.

SBCE could be incorporated in the treat-to-target algorithm for patients with CD. Randomized controlled trials are required to confirm its usefulness and reliability in this indication.

Core tip: The treatment goal in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) combines both clinical and endoscopic remission. Assessment of the small bowel (SB) is substantial because it may have a significant impact on prognosis. Small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) allows direct visualization of the entire SB mucosal surface. We conducted a systematic literature review that aimed to provide a global overview of the studies that assessed the use of SBCE in a treat-to-target strategy in patients with CD. SBCE could be useful for refining the disease location, assessing mucosal healing in patients receiving treatment, and monitoring patients in the post-operative setting.

- Citation: Le Berre C, Trang-Poisson C, Bourreille A. Small bowel capsule endoscopy and treat-to-target in Crohn's disease: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(31): 4534-4554

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i31/4534.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i31.4534

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which encompass Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic and disabling inflammatory gastrointestinal disorders. In contrast to UC in which lesions are strictly limited to the colon, CD is more heterogeneous and can affect the entire gastrointestinal tract, from the mouth to the anus. The Montreal classification of CD distinguishes anatomical disease location in the ileum (L1), colon (L2), and both the ileum and colon (L3)[1], each accounting for approximately one-third of patients who are diagnosed with CD[2]. About 10%–15% of patients have associated upper gastrointestinal lesions (L4)[3], which are isolated in 2%–3% of cases[4]. It has been demonstrated that jejunal disease is a significantly greater risk factor for stricturing disease and multiple abdominal surgeries than either esophagogastroduodenal or ileal (without proximal) disease[5-7].

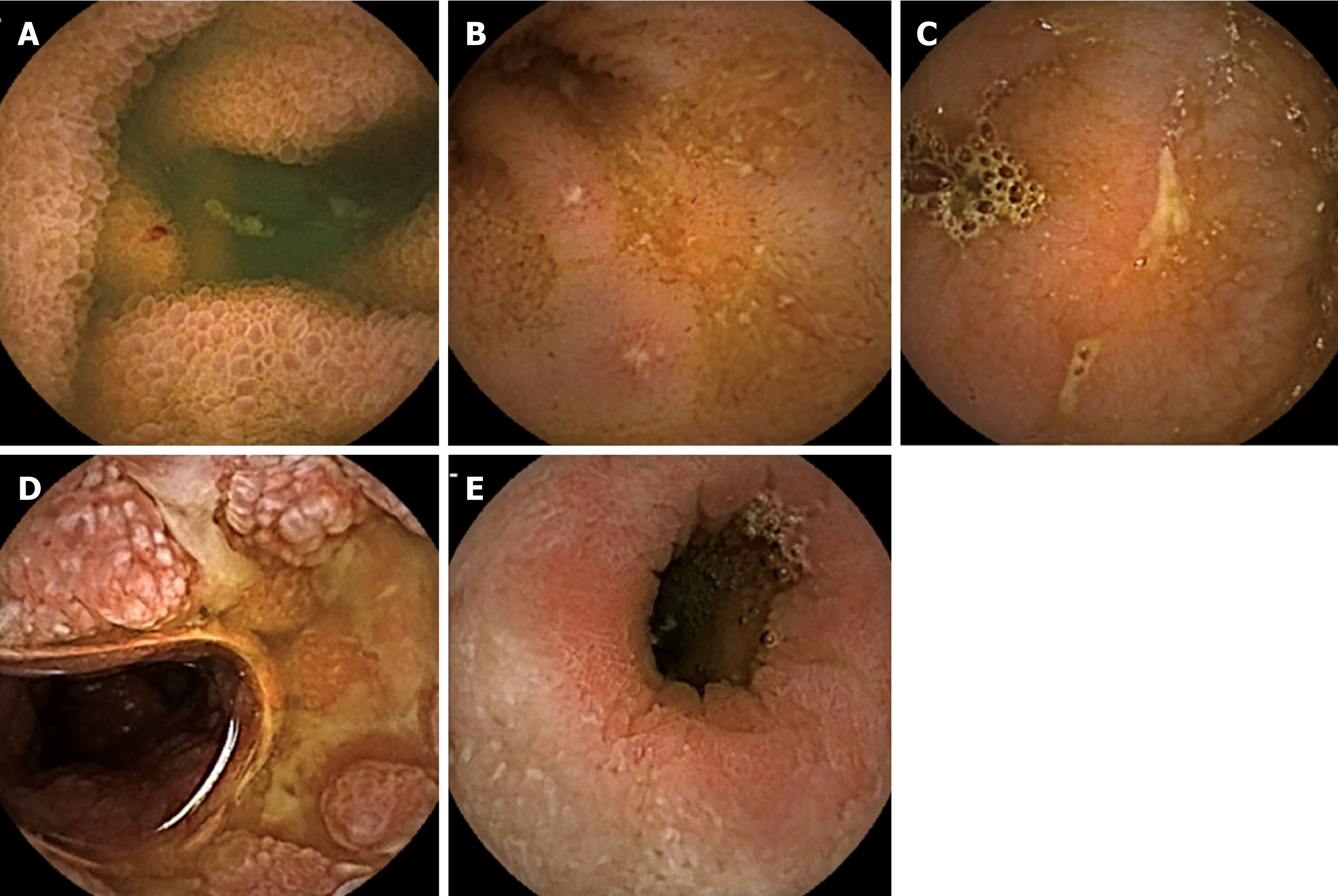

Assessment of the small bowel (SB) in patients with suspected or diagnosed CD is necessary because complete visualization of the entire length of the SB may have a significant impact on prognosis with potential therapeutic implications[8]. Device-assisted enteroscopy should be performed only when endoscopic therapy is indicated, because of its invasive nature[9]. Cross-sectional imaging (magnetic resonance enterography and computed tomography enterography) is highly accurate for the diagnosis of obstructive and fistulizing SB CD. Computed tomography enterography (CTE) is less suitable than magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) for follow-up monitoring because radiation exposure should be considered. Since its first approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in August 2001, small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) has become an important tool for assessing the SB, and it is particularly useful in areas of the gastrointestinal tract that are not accessible to conventional endoscopy. In a recent prospective study assessing whether SBCE or MRE that was performed after the initial diagnosis may alter the original disease classification, SBCE was more sensitive for detection of previously unrecognized locations, while MRE was superior for detection of phenotype shift[10]. Therefore, SBCE and MRE are probably complementary, because MRE assesses transmural involvement, while SBCE allows direct visualization of the mucosal surface of the SB. Five main lesions are associated with CD, although not specific – edema, aphthoid erosions, superficial and deep ulcerations, and stenosis (Figure 1).

Until recently, therapeutic strategies relied on a progressive and step-wise approach that was based solely on IBD-related symptoms. However, evidence is now accumulating that demonstrates the weak correlation that exists between symptoms and endoscopic disease activity in patients with CD[11-13]. Thus, the “treat-to-target” paradigm was developed in 2015, and it is based on regular and objective assessment of disease activity, and subsequent adjustment of the treatment[14]. The treatment goal has evolved to a new concept, which is achieving and maintaining deep remission, combining both clinical and endoscopic remission[15]. In patients with CD, the STRIDE consensus defined endoscopic remission as resolution of ulceration at ileocolonoscopy or resolution of inflammation findings on cross-sectional imaging when endoscopy cannot adequately evaluate inflammation[15]. However, as discussed above, MRE may often underestimate mucosal lesions, and SBCE could play a key role to play in this tight monitoring of patients with CD.

Both European and American guidelines now recognize SBCE as a useful adjunct in diagnosising SB CD in patients in whom there is a high clinical suspicion for CD, because it has a high negative predictive value in this indication[9,16]. In 2009, an international consensus aimed to define the role of SBCE in the follow-up of patients with IBD, suggesting that SBCE “may identify lesions in the small bowel that have not been detected by ileocolonoscopy after ileocolic resection” and that it “has a potential role in the assessment of mucosal healing after drug therapy”, but there was little of evidence to support this suggestion[17]. At that time, there is no recommendation for the use of SBCE during patient follow-up.

Here, we conducted a systematic literature review that aimed to investigate the impact of SBCE in a treat-to-target strategy in patients with CD.

An electronic literature search was conducted in PubMed and the Cochrane library using the following search terms: “capsule endoscopy”, in combination with “Crohn’s disease” or “inflammatory bowel disease” or “ileitis” or “enteritis”, and with synonyms of “treat-to-target” or “monitoring” or “post-operative recurrence”. The search was conducted in early February 2019 and included citations beginning from January 1, 2000. We restricted our search to studies that were published in English and we excluded studies related to animal research. Supplementary Table 1 provides the PubMed literature search strategy in detail. Duplicate articles identified in both PubMed and Cochrane library were manually deleted. To identify additional relevant studies, we checked the reference lists of the selected articles.

| Ref. | Study design | Sample size | Patient population | Compared modality | CE lesions considered diagnostic for CD | Positive SB findings | Impact in patient management1 |

| Reclassification of Crohn’s disease location | |||||||

| Chong et al[28], 2005 | Prospective, blinded | 43 | Group 1: Known CD (n = 22) Group 2: Suspected CD2 (n = 21) | Push enteroscopy and enteroclysis | ≥ 1 erosion/ ulcer | Group 1: 17/22 (jejunum, n = 7) vs 3/22 at push enteroscopy, P < 0.001 and 4/21 at enteroclysis, P < 0.001 Group 2: 4/21 (jejunum, n = 2), no statistically significant difference vs other modalities | 30/43 (70%) Group 1: 16 (73%) Group 2: 14 (67%) |

| De Bona et al[38], 2006 | Prospective | 38 | Suspected CD2 Group 1: Ongoing symptoms (n = 12) Group 2: Ongoing symptoms and inflammatory biomarkers3 (n = 26) | NA | Diagnostic if > 3 erosions/ ulcerations Suspicious if ≤ 3 and/or nodular pattern | Diagnostic: 13/38 (34.2%) (jejunum, n = 5) Suspicious: 2/38 (5.3%) Group 1: 1/12 (8.3%) Group 2: 14/26 (46.2%) P = 0.022 | 15/38 (39.5%) i.e., 100% of patients with positive CE findings |

| Efthymiou et al[29], 2009 | Prospective, blinded | 55 | Group 1: Known CD (n = 29) Group 2: Suspected CD2 (n = 26) | Enteroclysis | Diffuse erythema, erosions, > 3 aphthoid ulcers, ulcers of different shape and strictures | Group 1: 20/29 (jejunum, n = 8) vs 11/27 at enteroclysis4, incremental diagnostic yield= 33.4% (P = 0.035) Group 2: 16/26 (jejunum, n = 6), vs 6/20 at enteroclysis5, incremental diagnostic yield = 35.0% (P = 0.039) | - |

| Tukey et al[78], 2009 | Retrospective | 105 | Suspected CD2 | NA | Any ulcers | 39/105 (37%) Prevalence rate of CD diagnosis after a 12-mo follow-up = 13% Se 77%, Sp 89%, PPV 50%, NPV 96% | - |

| Mehdizadeh et al[39], 2010 | Retrospective | 134 | Known CD | NA | Diagnostic if > 3 ulcerations Suspicious if ≤ 3 ulcerations | Diagnostic: 52/134 (38.8%) Suspicious: 17/134 (12.7%) Jejunum lesions 53%, proximal ileum lesions 67% | 52/134 (38.8%) i.e., 100% of patients with positive CE findings |

| Lorenzo-Zúñiga et al[40], 2010 | Retrospective | 14 | Known CD | NA | ≥ 7 mucosal breaks or ulcerations | 12/14 (86%) According to indications of CE: Abdominal pain = 3/3 Anemia = 5/5 Disease extent re-evaluation = 4/6 | 9/14 (64%) i.e., 100% of patients in whom CE was performed because of abdominal pain, 80% for anemia, 33% for disease extent re-evaluation |

| Petruzziello et al[31], 2010 | Prospective | 64 | Known CD of the distal ileum (n = 32) Control group (n = 32) | SICUS | > 3 aphthoid ulcers, deep ulcers, stricture(s) | CD group: 16/32 (50%) with upper SB lesions vs 3/32 (9%) at SICUS, 30/32 (93%) with distal SB lesions vs 30/32 (93%) at SICUS Control group: 0/32 (0%) | - |

| Dussault et al[79], 2013 | Retrospective | 71 | Known CD | NA | Moderate: erythema and few aphthoid ulcers Severe: multiple and/or deep ulcers and/or stenosis | Moderate: 32/71 (45.1%) Severe: 12 (16.9%) According to indications of CE: Anemia = 4/6 Symptoms = 11/25 Disease re-evaluation = 28/37 | 38/71 (53.5%) i.e., 75% of patients with severe lesions and 53% with moderate lesions |

| Kalla et al[80], 2013 | Retrospective | 315 | Known (n = 50) or suspected2 (n = 265) CD | NA | > 3 ulcers with erythema or edema | Known CD: 33/50 (66%) (jejunum, n = 1 / diffuse, n = 16) Suspected CD: 45/265 (17%) (jejunum, n = 5 / diffuse, n = 7) | Known CD: 73% Suspected CD: 90% of patients with positive CE findings |

| Flamant et al[81], 2013 | Retrospective | 108 | Known CD (32 L1, 25 L2, 51 L3) | NA | Diffuse erythema and edema, linear/ circumferential ulcerations, ≥ 3 aphthous ulcers, or stenosis | 68/108 (63%) (jejunum, n = 60 of whom n = 18 i.e., 17% only in the jejunum) Restricted colonic location of the disease associated with a significantly decreased risk of jejunal lesions by 80% (OR = 0.21, P = 0.002) | - Jejunal lesions=sole independent factor associated with increased risk of clinical relapse (HR = 1.99, P = 0.02) |

| Cotter et al[82], 2014 | Retrospective | 50 | Known CD | NA | Moderate: Lewis score ≥ 135 Severe: Lewis score > 790 | Moderate: 33/50 (66%) Severe: 11/50 (22%) | Proportion of patients on thiopurines and/or biologics increasing from 2/50 (4%) to 15/50 (30%) after CE, P = 0.023 |

| Urgesi et al[41], 2015 | Retrospective | 492 | Suspected CD on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding | NA | Mucosal fissure, ulcers of different shape, cobblestoning mucosa, aphthous ulcers, stricture(s), erythema/edema, loss of villi | 94/492 (19.1%) (jejunum, n = 31) | 64/94 -68%) i.e., 100% of confirmed CD |

| Greener et al[10], 2016 | Prospective | 79 | Known CD | MRE | Lewis score ≥ 135 | Proximal disease location detected by CE in 51% of patients vs 26% by MRE (P < 0.01) (isolated proximal lesions, n = 9) | - |

| Chao et al[83], 2018 | Retrospective | 197 | Suspected CD in elderly patients2 | NA | Lewis score > 790 | 8/197 (4.1%) | 4/197 (2.0%) i.e., 50% of patients with positive CD findings |

| Carter et al[30], 2018 | Prospective, blinded | 50 | Suspected CD2 | Intestinal ultrasound | Lewis score ≥ 135 | Similar diagnostic yield: 19/50 (38%) for SBCE and intestinal ultrasound, correlation r = 0.532, P < 0.001 | - |

| Sorrentino and Nguyen[32], 2018 | Retrospective | 43 | Known CD (20 never had surgery, 23 in the post-operative setting) | Ileocolono-scopy and MRE/CTE and CRP/FL | Any ulcerations or multiple erosions | Surgery-naïve group: 13/20 (65%) vs 8/20 (40%) at ileocolonoscopy vs 9/206 (45%) at imaging vs 12/207 (60%) at biomarkers Post-operative group: 20/23 (87%) vs 16/238 (70%) at ileocolonoscopy vs 0/239 (0%) at imaging vs 13/23 (57%) at biomarkers | Surgery-naïve group: 6/20 (30%) Post-operative group: 12/23 (52%) |

| Hansel et al[84], 2018 | Prospective | 50 | Known CD with normal imaging | NA | Diffuse erythema and edema, linear or circumferential ulceration(s), ≥ 3 aphthous ulcers, or stenosis | 14/50 (28%) with proximal SB lesions (duodenum, jejunum) | 17/50 (34%) |

| González-Suárez et al[33], 2018 | Retrospective | 47 | Known CD (n = 32) or suspected (n = 15) CD | MRE | Lewis score ≥ 135 | 36/47 (76.6%) vs 21/47 (44.7%) at MRE, P = 0.001, of which jejunal lesions: 15/47 (31.9%) vs 3/47 (6.4%), P = 0.02 | - |

| Xavier et al[34], 2018 | Retrospective | 71 | Perianal CD (n = 17) and non-perianal CD (n = 54) | NA | Villous edema, erosions, ulcers or stenosis | Perianal CD: 94.1% vs 66.6% in non-perianal CD (P = 0.03), with more frequently a Lewis Score ≥ 135: 94.1% vs 64.8% (P = 0.03), and higher Lewis scores in the first and second tertiles but not in the third tertile | - |

| Reclassification of inflammatory bowel disease type | |||||||

| Maunoury et al[35], 2007 | Prospective | 30 | IBD-U with negative ASCA/ANCA and normal SBFT | NA | ≥ 3 ulcerations | 5/30 (16.7%) (jejunum, n = 4) | - |

| Lopes et al[36], 2010 | Prospective | 18 | IBD-U (n = 14) or IC (n = 4) with negative ASCA/ANCA | NA | Diagnostic if ≥ 4 erosions/ulcers and/or stricture(s) Suspicious if < 4 and/or focal villi denudation | Diagnostic: 7/18 (38.9%) Suspicious: 9/18 (50.0%) Jejunum and proximal ileum lesions: 8/18 (44.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Long et al[37], 2011 | Retrospective | 124 | CD (n = 86) or IC (n = 15) or pouchitis (n = 23) | NA | Erythema, few aphthae/ulcers, multiple aphthae/ulcers, stenosis | CD: 67/86 (77.9%) IC: 7/15 (46.7%) Pouchitis: 15/23 (65.2%) | Medication: CD: 34/86 (39.5%) IC: 6/15 (40.0%) Pouchitis: 13/23 (56.5%) Surgery: CD: 11/86 (12.8%) IC: 6/15 (40.0%) Pouchitis: 1/23 (4.4%) |

Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of articles that were identified by the search strategy after duplicates were removed (CLB and AB). Any disagreements regarding the inclusion of articles were solved by discussion until consensus was reached. Reviewers were not blinded to the study authors’ affiliation or journal name. Following the initial screening of abstracts, all articles containing information about SBCE in the context of treat-to-target strategy in patients with CD were included. Studies without any outcome related to treat-to-target strategy or to CD were excluded, as were studies related to pediatric populations and reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, and letters to the editor. Full-text articles were retrieved, and reference lists were screened manually to identify additional studies.

The following data were extracted for each included study: Name of the first author, year of publication, study design, patient population and sample size, capsule endoscopy findings, and comparator modality, if applicable. For studies assessing disease reclassification, the impact of SBCE findings in patient management was reported. For studies assessing mucosal healing during treatment, ongoing treatment and prior biologic exposure were noted. For studies assessing the use of SBCE in the post-operative setting, risk factors for post-operative recurrence, indications for surgery, interval between surgery and endoscopic re-assessment, post-operative prophylactic treatment, and the rate of clinical recurrence were noted.

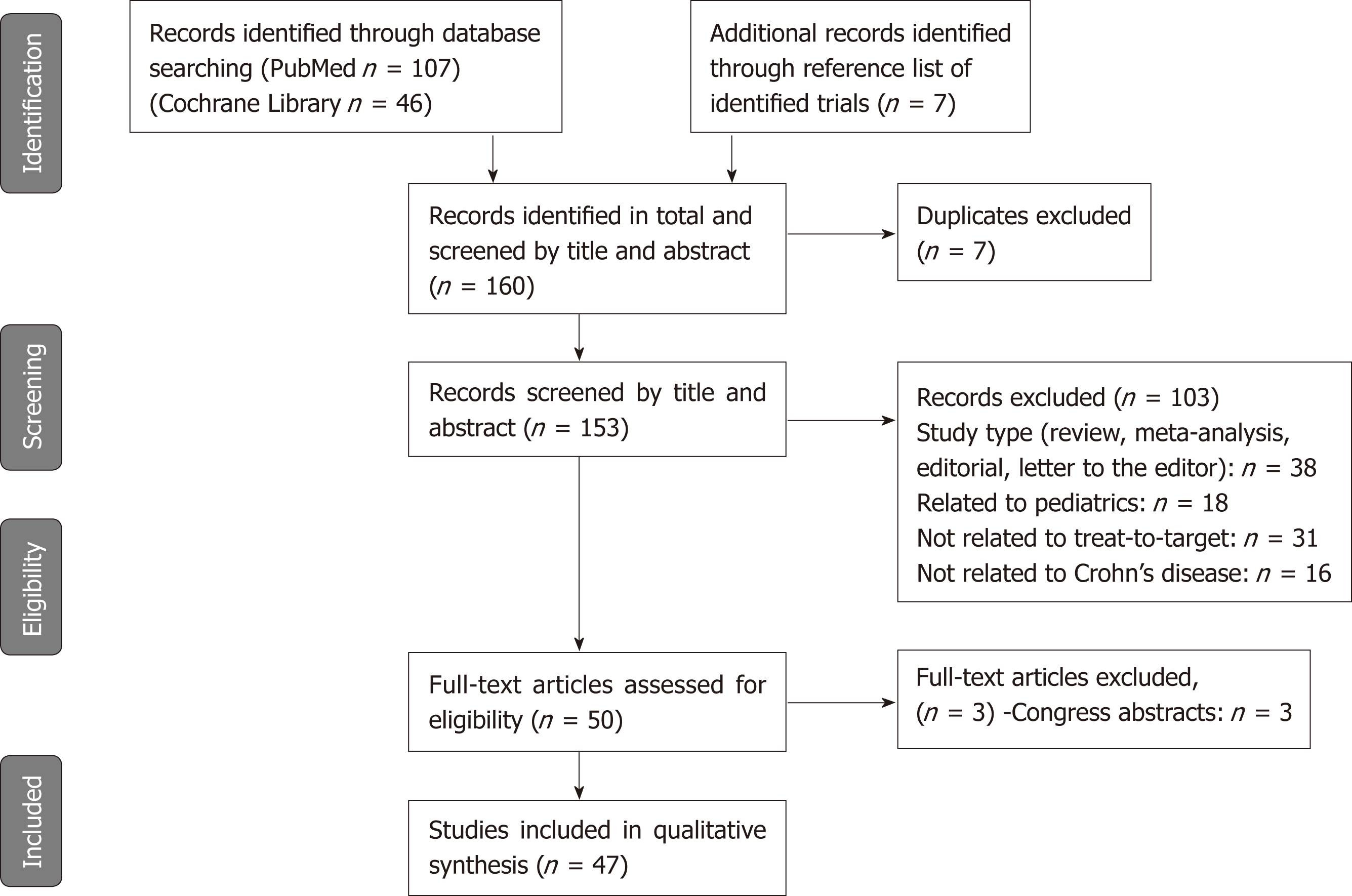

The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses was used to conduct and report the results of this review[18]. The first part of this systematic review focused on the indexes that were used to describe CD lesions at small bowel capsule endoscopy. The findings were then organized according to the context of SBCE use when monitoring a patient who was diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease, as follows: (1) Reclassifying disease location or phenotype; (2) Assessing mucosal healing in patients with CD; and (3) Monitoring patients in the post-operative setting.

There were 153 studies identified after the electronic search. Seven additional studies were identified from a review of the reference lists from included articles. Based on the information provided in the abstracts, 103 studies were excluded, as well as seven duplicates. Fifty articles were then selected for full-text review. Among those articles, three were excluded, and 47 articles were finally included in this review. The PRISMA diagram describing the article search process is presented in Figure 2.

Supplementary Table 2 summarizes the studies that assessed the two indexes that have been developed to date to describe CD lesions at SBCE. The first index is the Lewis score, which was developed in 2007[19] and validated in 2014, and it has excellent interobserver agreement in patients with known SB CD[20]. A score below 135 is considered to be normal, while a score above 790 reflects moderate to severe inflammation. Between these two values, SB inflammation is considered to be mild[19]. This score was also useful as a diagnostic tool for patients with suspected CD, with a sensitivity and positive predictive value of 82.6%, and a specificity and negative predictive value of 87.9%[21].

| Ref. | Study design | Sample size | Treatment evaluated | Prior biologic exposure | Interval between the CE | CE findings considered for assessing mucosal healing | Positive SB findings before treatment | Positive SB findings after treatment | P-value |

| Efthymiou et al[85], 2008 | Prospective, blinded | 40 | CS (60%) Mesalamine (70%) Azathioprine (10%) Infliximab (5%) Metronidazo-le (20%) | - | After achievement of clinical remission: 4 wk (75%) | Number of apthous ulcers, mean ± SE | 26.0 ± 7.5 | 12.7 ± 2.3 | 0.07 |

| 6 wk (15%) | Number of large ulcers, mean ± SE | 8.3 ± 1.4 | 5.0 ± 0.8 | 0.01 | |||||

| 8 wk (10%) | Percentage of the SBTT in which any endoscopic lesion was visible, mean ± SE | 22.0 ± 3.1 | 17.8 ± 2.5 | 0.08 | |||||

| Tsibouris et al[86], 2013 | Prospective, blinded | 1021 | - | - | ≥ 15 d after CDAI dropped < 150: 2-3 mo; (26.5%) 3-6 mo; (19.6%) 6-12 mo; (53.9%) | CECDAI score, mean ± SD | 14 ± 6 | 4 ± 2 | - |

| Niv et al[44], 2014 | Prospective, blinded | 19 | Copaxone (68.4%) 5-ASA (52.6%) Antibiotics (15.8%) CS (5.3%) IS (10.5%) Vitamins (26.3%) Others (36.8%) | - | 12 wk | Lewis score, mean ± SD | 1730 ± 1780 | No correlation between changes in CDAI/IBDQ and Lewis score2 | - |

| Hall et al[42], 2014 | Prospective, blinded | 43 | Adalimumab (84%) 160 mg W0, 80 mg W2, then 40 mg /2 wk or Azathioprine (16%) 2-2.5 mg/kg | Naïve 38/43 Exposed 5/43 | 52 wk3 | Complete MH = Absence of ulcers, n (%) Normalizatio-n of CECDAI score < 3.5, n (%) Change in CECDAI score, n (%) | - - CECDAI < 3.5: 4/43 (9%) 3.5 ≤ CECDAI < 5.8: 13/43 (30%) CECDAI ≥ 5.8: 26/43 (61%) | Complete MH: 12/28 (43%) CECDAI < 3.5: 2/28 (7%) CECDAI ≤ 3.5 < 5.8: 6/28 (21%) CECDAI ≥ 5.8: 8/28 (29%) | < 0.0001 |

| Kopylov et al[45], 2015 | Prospective | 52 | None (15.4%) 5-ASA (9.6%) Thiopurine (36.6%) Anti-TNF (26.9%) Anti-TNF+IS (11.5%) | - | NA Included patients were all in clinical remission (CDAI < 150) and had only one CE. | MH = Lewis score < 135 | NA | MH: 8/52 (15.4%) 135 ≤ Lewis < 790: 33/52 (63.5%) Lewis score ≥ 790: 11/52 (21.2%) | - |

| Shafran et al[43], 2016 | Prospective, open-label | 15 | Certolizumab pegol 400 mg W0, W2, W4 then /4 wk | Naïve 3/15 Exposed 12/154 | 24 wk in responders | Lewis score, mean | 1663 | 226 | - |

| Aggarwal et al[46], 2017 | Prospective, blinded | 43 | None (14%) 5-ASA (60%) CS (12%) IS (74%) Anti-TNF (21%) | - | NA Included patients were all in clinical remission (CDAI < 150) and had only one CE. | MH = Lewis score < 135 | NA | MH: 17/43 (40%) 135 ≤ Lewis < 790: 19/43 (44%) Lewis score ≥ 790: 7/43 (16%) Significant correlation between Lewis score and fecal calprotectin (r = 0.82, P < 0.0001) | - |

| Mitselos et al[47], 2018 | Retrospective | 30 | None (37%) 5-ASA (17%) Budesonide (10%) Azathioprine (10%) Anti-TNF (20%) Anti-TNF+IS (6%) | - | NA Included patients had only one CE (60% in both clinical and biochemical remission) | MH = Lewis score < 1355 | NA | MH: 6/15 (40%) Weak correlation between CDAI and Lewis score (r = 0.32, P = 0.088) and between CRP and Lewis score (r = 0.52, P = 0.004) | - |

| Nakamura et al[87], 2018 | Prospective, blinded | 92 | None (27%) 5-ASA (18%) Thiopurines (17%) Infliximab (20%); Adalimumab (10%) Elemental diet (5%) CS (3%) | Naïve 38/92Exposed 54/92 | 6 mo in the active group (40/92) Non-active patients ended the study at baseline (52/92) | Lewis score, mean MH = Lewis score of 0 Active CD: Lewis score > 135 | 458 | 233 MH: 2/296 Improvement of LS in all 7 patients who received biologics, and in 8/11 (73%) of asymptomatic patients receiving additional medication | 0.0004 |

The second index was developed in 2008 and it is called Capsule Endoscopy Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CECDAI). It ranges from 0 to 36, and the correlation between two observers is also excellent[22]. This score was validated in 2012 in a cohort of 50 patients with known SB CD[23]. Two recent studies showed a significant correlation between the Lewis and CECDAI scores in patients with known SB CD, with correlation coefficients of r = 0.632 (P < 0.0001)[24] and r = 0.81 (P = 0.0001)[25], respectively. Lewis score thresholds of 135 and 790 correspond with CECDAI levels of 3.8 and 5.8, respectively[24].

Compared to the MRE scores, the Lewis score was significantly correlated with both MaRIA and Clermont scores (r = 0.50, P = 0.001 and r = 0.53, P = 0.001, respectively), especially for detecting moderate to severe inflammation[26]. However, the Lewis score was weakly correlated with clinical activity as measured by the Harvey Bradshaw index (r = 0.213, P = 0.019) and no correlation was found between CD activity index (CDAI) and the CECDAI[23]. The Lewis score moderately correlated with C-reactive protein (r = 0.326, P < 0.001)[27], and a moderate correlation was demonstrated between SBCE scores and fecal calprotectin (r = 0.48, P = 0.001 for Lewis score, and r = 0.53, P = 0.001 for CECDAI)[25].

Table 1 describes the key studies that show the potential impact of SBCE on disease reclassification of patients suspected or diagnosed with IBD, and gives an overview of the subsequent therapeutic management. Most of those studies focused on reclassifying the CD location by assessing SB in patients with known or suspected CD. All showed positive SBCE findings, including jejunal lesions that had not previously been visualized using conventional endoscopy or imaging. All of the studies that compared SBCE to other diagnostic modalities showed a significant incremental diagnostic yield of SBCE. Compared to push enteroscopy, SBCE had an incremental diagnostic yield of 63.6% in patients with known CD, although the difference was not significant in patients with suspected CD[28]. Two studies compared the diagnostic yield of SBCE to that of enteroclysis, and both demonstrated a significant incremental diagnostic yield of 62.0%[28] and 33.4%[29] in patients with known CD. In patients with suspected CD and negative ileocolonoscopy, an intestinal ultrasound and SBCE had a similar diagnostic yield (38%)[30]. However, in patients with known CD of the distal ileum, SBCE had an incremental diagnostic yield of 41% compared to the small intestine contrast ultrasonography (SICUS) for the detection of upper SB lesions, while the detection rate of distal SB lesions was similar for both modalities (93%)[31]. Compared to cross-sectional imaging, three studies demonstrated that SBCE was superior in detecting SB lesions[10,32,33], with an incremental diagnostic yield up to 31.9%[33], especially for the detection of proximal SB CD location[10,33]. However, the lesions that were considered for the diagnosis of CD varied greatly from one study to another, making it difficult to compare these studies.

A single study focused on the comparison of SBCE findings between CD patients with and without perianal disease, showing that patients with perianal involvement had significantly more relevant SB lesions (94.1% vs 66.6%, P = 0.03) and higher inflammatory activity with a Lewis score ≥ 135 (94.1% vs 64.8%, P = 0.03), especially in proximal SB segments, compared to patients without perianal CD[34].

Only three of the included studies focused on reclassifying the IBD type in patients who were diagnosed with IBD-unclassified, indeterminate colitis or pouchitis. The lesions that were considered for the diagnosis of CD were very different depending on the study. However, SBCE detected SB lesions allowing the physician to suspect or even make the diagnosis of CD in 16.7% to 50.0% of patients with IBD-unclassified or indeterminate colitis, and up to 65.2% of patients who were diagnosed with pouchitis following ileo-anal anastomosis[35-37].

For the impact on therapeutic management, most of the studies showed that SBCE findings led to a change in the dose or change of immunomodulatory agent, initiation of biologic treatment, or avoidance of surgery, in more than one-third of patients, and even in 100% of patients in four studies[38-41].

Table 2 summarizes the nine studies that evaluated the use of SBCE to assess mucosal healing in patients who were diagnosed with CD. All but one study had a prospective design. Most of these studies did not evaluate a specific treatment, except for two studies, one of which focused on adalimumab and azathioprine[42] and the other that focused on certolizumab pegol[43]. Another study was a sub-study of a prospective, randomized, double blind placebo-controlled study that assessed the safety, tolerability and efficacy of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®)[44]. In three of the nine included studies, there was no comparison between SBCE findings at baseline and during follow-up, because the included patients-most of whom were in clinical remission-had only one SBCE after treatment[45-47]. The SBCE findings that were considered for the assessment of mucosal healing differed according to the studies, although most of them were based on the calculation of the Lewis score, with a normal value below 135.

Overall, despite high heterogeneity in these studies, the results indicated that mucosal healing can be evaluated by SBCE to monitor the effect of medical treatment in patients with CD, with a significant correlation between the Lewis score and fecal calprotectin (r = 0.82, P < 0.0001)[46], while there was no significant correlation between this score and clinical activity as measured by the CDAI[44,47].

Only seven of the included studies focused on the monitoring of patients with CD in the post-operative setting. The results are summarized in Table 3. All but one of the studies were prospective, and they all had small-sized cohorts with less than 35 patients. The single retrospective study included 83 patients with no risk factor for post-operative recurrence. The design methodology varied greatly between studies, making them difficult to compare. First, indications for surgery were different depending on the study, with varying proportions of treatment failure, stenosis, and fistula or abscess. The existence of risk factors for post-operative recurrence was also variable between studies, especially for smoking (range, 11%–50%) and penetrating phenotype (range, 7%–58%). In some studies, post-operative prophylactic treatment was forbidden, while others allowed the use of immunosuppressive drugs or biologics. The interval between surgery and the endoscopic re-assessment was also extremely variable, ranging from less than 3 mo to 1 year. Finally, SBCE findings that were considered for defining post-operative recurrence were also different across studies, and they were mostly based on the Lewis score (≥ 135) or the Rutgeerts score (≥ i,1 or i,2)[48].

| Ref. | Study design | Sample size | Indication for surgery | Risk factors for POR | Post-operative prophylac-tic treatment | Compared modality | Interval between surgery and endosco-pic re-assess-ment | CE findings considered for defining POR | Rate of clinical recurrence, n (%) | Rate of endosco-pic recurren-ce, s (%) |

| Bourreille et al[49], 2006 | Prospective, blinded | 32 | Resistance to medical treatment (19%) Stenosis (37%) Fistula/abs-cess (44%) | - | None (28%) 5-ASA (22%) CS (3%) IS (9%) Others (44%) | Ileocolono-scopy | Median (IQR): 6 mo (4-7) | Rutgeerts score ≥ i,1 | - | Colonosco-py: 19/311 (61%) Se 90%, Sp 100% WCE: 21/31 (68%) Se 76%, Sp 91% SB lesions up to 72% |

| Biancone et al[50], 2007 | Prospective, blinded | 22 | Resistance to medical treatment (9%) Stenosis (64%) Fistula/abs-cess (14%) Other (13%) | Smoking (32%) Penetrating phenotype (23%) | Mesalamine (100%) | Ileocolono-scopy (gold standard), SICUS | 1 year | Ulcers, strictures, or stenosis in the neoterminal ileum and/or anastomosis | 0 (0%) | Ileocolonosc-opy: 16/172 (94%) SICUS: 17/172 (1 FP) (100%) WCE: 16/172 (94%) Se 93%, Sp 67% |

| Pons Beltrán et al[51], 2007 | Prospective, blinded | 24 | Resistance to medical treatment (21%) Stenosis (63%) Other (16%) | Smoking (50%) Penetrating phenotype (38%) | None (100%) | Ileocolono-scopy | Median (range): 254 d (118-439) | Rutgeerts score ≥ i,2 | 0 (0%) | Ileocolonos-copy: 6/24 (25%) WCE: 15/24 (63%) Jejunal lesions (54%) |

| Kono et al[52], 2014 | Prospective, blinded | 19 | - | Smoking (11%) Penetrating phenotype (58%) Prior resection (68%) | 5-ASA (39%) Anti-TNF (61%) | Ileocolono-scopy at 6-8 mo | mean ± SD: 17.3 ± 5.6 d then 216.9 ± 23.6 d | Lewis score ≥ 135, n (%) and Mean (range) | 0 (0%) | Week 2-3: 14/183 (78%) 428.3 (8-4264) 6-8 mo: 9/134 (69%) vs 3/6 (50%) at colonoscopy 196.1 (8-450) 5/13 (38%) with LS higher by ≥ 100 than shortly after surgery |

| Hausmann et al[53], 20175 | Prospective, blinded | 22 | - | Penetrating phenotype (18%) Prior resection (50%) | None (76%) Azathiopri-ne (6%) Adalimum-ab (18%) | Ileocolono-scopy at 4-8 mo | Mean (range): 57.5 (34 – 83) d then 220 (159 – 322) d | Modified Rutgeerts score ≥ i,2 | - | Week 4-8: 3/166 (19%) 4-8 mo: 7 6/12 (50%) vs 5/15 (33%) at colonoscopy |

| Han et al[54], 2018 | Retrospec-tive, blinded | 83 | Resistance to medical treatment (24.3%) Stenosis (75.7%) | None (100%) | None (100%) before date 1 After date 1 if POR: None (53.1%) Azathiopri-ne (21.6%) Infliximab (25.3%) | Group 1 (37/83): ileocolono-scopy + CE (date 1) then repeat colonoscopy (date 2) Group 2 (46/83): ileocolono-scopy (date 1 and 2) | Date 1: 3-7 mo; after surgery Date 2: 1 year after date 1 | Rutgeerts score ≥ i,2 in the terminal ileum or > 5 aphthous lesions in proximal SB or ulcers in proximal SB | Group 1: 1/37 (2.7%) Group 2: 10/46 (21.7%) P = 0.019 | Date 1: Group 1: 13/37 (35.1%) at IC vs 24/37 (64.9%) at CE Group 2: 15/46 (32.6%) at IC (P = 0.809) Date 2: Group 1: 8/37 (21.6%) Group 2: 20/46 (43.5%) (P = 0.036) |

| Kusaka et al[55], 2018 | Prospective | 25 | - | Smoking (22%) Penetrating phenotype (7%) Prior resection (48%) | 5-ASA (96%) Elemental diet (30%) IS (19%) Anti-TNF (59%)8 | - | < 3 mo | Lewis score ≥ 135 | 5/25 (20%) | 21/25 (84%) mean ± SD: 751.3 ± 984.0 Clinical recurrence rate significantly higher in the group with highest third tertile score (distal SB) |

All but one study compared SBCE to ileocolonoscopy, which is the current gold standard for assessing post-operative recurrence in patients with CD. Although two studies showed that the sensitivity of SBCE in detecting recurrence in the neoterminal ileum was not superior to that of ileo-colonoscopy[49,50], the other studies showed that SBCE could detect post-operative recurrence more frequently than ileo-colonoscopy[51-54], and with a better tolerance[51]. Moreover, two studies demon-strated that SBCE detected lesions outside the scope of ileocolonoscopy in more than half of the patients[49,51], which might be a substantial advantage as compared to conventional endoscopy because of the prognostic impact of these lesions on therapeutic management.

The retrospective study was also interesting and evaluated the impact of SBCE findings on clinical outcomes in asymptomatic patients without medical prophylaxis after ileocolonic resection. Two groups of patients were compared. Group 1 underwent ileocolonoscopy and SBCE within 1 year after surgery, whereas group 2 only had ileocolonoscopy. Patients with endoscopic recurrence detected by either ileocolonoscopy or SBCE received azathioprine or infliximab. One year later, disease activity was re-assessed by ileocolonoscopy. The clinical recurrence rate was 2.7% in group 1 compared with 21.7% in group 2 (P = 0.019), and the endoscopic recurrence rates were 21.6% and 43.5% (P = 0.036), respectively[54], suggesting that SBCE could be useful in detecting post-operative recurrence especially in patients without pharmacological prophylaxis.

This is reinforced by the results of another study that aimed to assess residual SB lesions in 25 CD patients immediately after surgery (< 3 mo). The mean Lewis score was 751.3, and 84.0% had endoscopic activity, and these residual lesions, especially in the distal SB, were associated with postoperative clinical recurrence[55], suggesting that SBCE could be used to detect very early post-operative recurrence, particularly in patients without any risk factors who do not necessarily require prophylactic treatment according to the current guidelines.

This systematic review aimed to provide a global overview of the published data on the use of SBCE for close monitoring of patients with CD. In a treat-to-target strategy, SBCE could be useful for refining disease location and prognosis, assessing mucosal healing in patients receiving treatment, and monitoring patients in the post-operative setting.

In contrast to disease phenotype that has long been recognized as an independent risk factor for poor outcome when complicated, disease location was not considered to be substantial in defining disease prognosis until recently. Several studies have now demonstrated that jejunal disease is associated with an increased risk of stricturing disease and abdominal surgeries as compared to either esopha-gogastroduodenal (EGD) or ileocolonic disease[5-7]. Clarity in disease distribution is therefore crucial, and pediatricians have already modified and modernized the Montreal classification, all the more so as upper gastrointestinal involvement is much more frequent in children than in adults (30%-80% vs 10%-15%). The Paris classification tried to avoid any ambiguity in the meaning of upper gastrointestinal lesions (L4), by distinguishing the lesions that are proximal to the ligament of Treitz (L4a) and those that are distal to the ligament of Treitz but proximal to the distal one-third of the ileum (L4b)[56]. Further characterization of the L4 phenotype in the Montreal classification into three specific subgroups including L4-EGD, L4-jejunal, and L4-proximal ileal disease may be warranted, similar to the Paris classification of pediatric patients. This was suggested by a recent retrospective cohort study in which L4 disease had a worse prognosis compared to non-L4 disease, and within L4 disease, the phenotype of L4-jejunal and L4-proximal ileal disease indicated a higher risk for intestinal surgery[57]. Thus, SBCE could be particularly appropriate to detect lesions outside the scope of conventional endoscopy because it seems to be more sensitive than imaging to detect a previously unrecognized disease location[10]. Similarly, SBCE could also be valuable in patients with IBD-U, indeterminate colitis or pouchitis, as it may lead to the diagnosis of CD in up to two-thirds of patients, impacting the therapeutic management in most cases.

With the advent of the treat-to-target paradigm in IBD patients, endoscopic remission has become part of the therapeutic goal, combined with clinical remission, leading to the concept of “deep remission”. Given the weak correlation that exists between symptoms and endoscopic disease activity in patients with CD, the STRIDE consensus recommended assessment of endoscopic activity at 6- to 9-mo intervals during the active phase of CD[15]. Thus, SBCE appears to be more feasible as compared to conventional endoscopy, with better patient acceptance, and more sensitive to assess mucosal inflammation than cross-sectional imaging. This review showed that mucosal healing can be assessed by SBCE to monitor the effect of medical treatment in patients with CD, with a significant correlation between the Lewis score and fecal calprotectin (r = 0.82, P < 0.0001)[46]. However, the definition of endoscopic remission as assessed by SBCE remains unknown because there is currently no consensus on the therapeutic objective to reach in luminal SB CD (normalization of SBCE or absence of deep or superficial ulcerations). Similarly, endoscopic re-assessment should be timely in the post-operative setting to detect post-operative recurrence at an early stage. Ileocolonoscopy remains the gold standard for this indication and it is recommended within the first year after surgery, when treatment decisions may be affected[58]. This review demonstrated that SBCE could effectively detect post-operative recurrence to a similar extent as ileocolonoscopy, and that it can detect proximal SB lesions beyond the reach of the colonoscope in more than half of the patients[49,51]. SBCE could be used to detect very early post-operative recurrence especially in patients without any risk factors who do not necessarily require pharmacological prophylaxis immediately after surgery[54,55].

Randomized controlled trials are required to confirm the usefulness and reliability of SBCE in such indications before its incorporation in treat-to-target algorithms. However, validated criteria for the diagnosis of CD at SBCE are needed because some studies have questioned the specificity of SBCE findings for CD, and to date, the lesions that are used to define CD vary greatly across studies. A panel of international experts is currently putting together a three-round Delphi consensus to define exactly which SBCE findings constitute a diagnosis of CD, as has been done recently for the terminology and description of the most frequent and relevant vascular lesions in SBCE[59]. These terms and descriptions will be useful for both medical research and daily practice.

In addition, the practical modalities of performing SBCE may highly influence the results. There are currently five available CE systems to explore the SB: PillCam SB3 (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland), EndoCapsule (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), MiroCam (Intromedic, Seoul, South Korea), CapsoCam (CapsoVision, Saratoga, United States), and the Pillcam COLON2 (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland). The Pillcam COLON2 also visualizes the SB, even though it was designed to explore the colon. Although all these devices are based on comparable technologies, significant differences exist in the number of cameras, frame rate, field of view, viewing direction, image resolution and battery life[60]. These differences could theoretically influence diagnostic performance, but there are currently no available head-to-head studies comparing these devices in patients with CD. Most of studies have been performed using the PillCam SB because this CE system has dominated the world market for many years.

In addition to the choice of the CE system, SB preparation before the SBCE may improve visualization, diagnostic sensitivity, and transit time. Optimal SB preparation remains controversial. Multiple studies examined the effect of different bowel cleansing regimens on mucosal visualization, diagnostic yield and completion rates, and several meta-analyses tried to determine the best strategy, but conflicting results have been obtained[61-64]. Prokinetics do not seem to improve the diagnostic yield and should probably not be used[62,63]. Simethicone and laxatives, including polyethylene glycol (PEG) and sodium phosphate, could be used because they seem to improve SB quality visualization. However, their effect on diagnostic yield remains controversial[61,63-65]. A recent study demonstrated in a cohort of 860 patients that clear liquid fasting had similar preparation quality and diagnostic yield compared to a 2-L PEG protocol[66]. Thus, there is still no consensus on the use of bowel cleansing before SBCE in patients examined for CD.

Reading protocols might also impact the diagnostic accuracy of SBCE. Time-consuming video analysis is a substantial limitation of using SBCE in daily practice, and the available software, Given RAPID Reader®, for SBCE analysis has developed several techniques to shorten reading times. Physicians can first modify the viewing mode from single to dual or quad view, and the frame rate can be adjusted from 5 to 40 frames per second (fr/s). A recent study compared a single view, dual view, and quad view at different frame rates using a SB video sequence with 60 pathological images of SB angioectasias, and it showed that both viewing mode and frame rate significantly influence lesion detection, with an increase in detection rate using the dual and quad view compared to single view, but a decrease in the number of positive findings when increasing the frame rate[67]. However, for CD, increasing the viewing speed may be feasible, as illustrated by another study in which overlooked lesions did not change the final result of the examination[68], given that CD lesions are multiple and often widespread in the SB. Another way to shorten reading times is to use the Quickview function provided by Given RAPID Reader® which filters and reduces the number of images shown to the capsule endoscopist based on a specific algorithm that was developed by the manufacturer. Sampling rates between 2% and 80% can be chosen. A recent study showed that the frequencies of the selected lesions picked up by Quickview mode using percentages for sensitivity settings of 5%, 15%, 25%, and 35% were 61%, 74%, 93%, and 98%, respectively. With a 25% sampling rate, only 7% of lesions were missed, and the reading time was reduced by approximately 50%[69]. Two other studies showed that despite a significant number of missed lesions, Quickview mode is a safe and time‐reducing method for diagnosing SB CD[70,71].

Finally, discontinuation of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is recommended at least 1 mo before SBCE because these drugs may induce SB mucosal lesions that are indistinguishable from those caused by CD[72].

This review showed that CE allows a direct and detailed evaluation of the entire SB mucosa with detection of the earliest CD lesions compared to imaging modalities, with the advantage of being a patient-friendly and noninvasive procedure. SBCE also proved to be cost-effective[73,74]. However, there are some limitations (Table 4), of which capsule retention is the main concern. For this risk, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) does not recommend routine use of the PillCam patency capsule before SBCE in patients with suspected CD without any obstructive symptoms. When SBCE is indicated in patients with established CD, ESGE recommends prior use of the Agile capsule to confirm functional patency of the SB[72]. Available data suggest that the PillCam patency capsule is a safe method for testing SB patency before SBCE, even in patients with a radiologically confirmed stricture[75], because symptomatic patency capsule retention is a very rare complication with a favorable prognosis, as demonstrated in a multicenter retrospective case series of 1615 cases[76].

| Advantages | Limitations |

| Less invasive than conventional endoscopy | Risk of capsule retention in stricturing CD |

| No need for sedation | No therapeutic or biopsy capability |

| High diagnostic yield comparable to other endoscopic or imaging modalities | SB evaluation may be incomplete due to: |

| Uncontrolled air insufflation | |

| Retention or delayed transition | |

| Limited battery life | |

| Impossible to maneuver | |

| Direct mucosal evaluation | Longer procedure time compared to other modalities |

| Patient-friendly | Analysis is time-consuming for the physician |

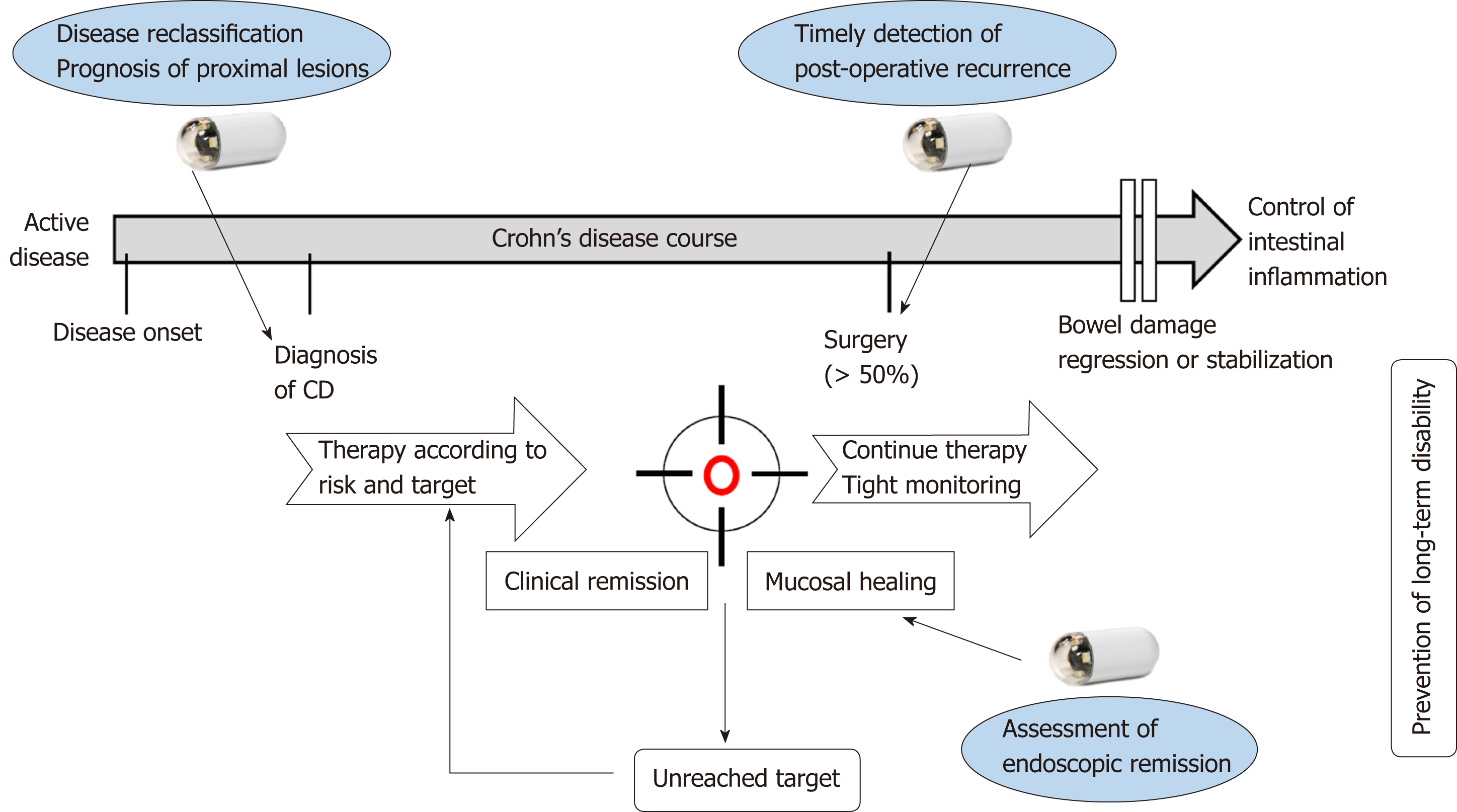

Taken together, the results of this systematic review demonstrate that SBCE might be used for close monitoring and incorporated into the treat-to-target algorithm for patients diagnosed with CD, in order to regularly evaluate disease activity (Figure 3). The development of pan-enteric video capsule endoscopy should allow broadening of the indications for SBCE in patients with CD[77]. Finally, artificial intelligence is expected to help reduce the burden on capsule endoscopists by automatically detecting and classifying lesions with the development of deep learning systems.

This systematic review aimed to provide a global overview of the potential applications of SBCE in a treat-to-target strategy in patients with CD. SBCE should, therefore, be useful for classifying disease location at baseline, with a prognostic impact of proximal SB lesions. SBCE may also allow physicians to assess the achievement of endoscopic remission in patients receiving treatment, and to detect early post-operative recurrence. However, randomized controlled trials are required to confirm the usefulness and reliability of SBCE for these indications, and validated criteria for the diagnosis of CD at SBCE are eagerly awaited.

Crohn’s disease (CD) may affect any part of the digestive tract. Proximal small bowel (SB) lesions, especially jejunal lesions, are associated with an increased risk of stricturing disease and abdominal surgeries compared to esophagogastroduodenal or ileocolonic disease. Thus, assessing the SB may have a significant impact on prognosis. The treat-to-target paradigm was developed in 2015 because of the poor correlation that exists between symptoms and endoscopic disease activity in patients with CD. This concept is based on regular and objective assessment of disease activity and subsequent adjustment of treatment, with the final aim of reaching both clinical and endoscopic remission. Until now, the treat-to-target strategy is based on the assessment of mucosal lesions seen by endoscopy into the ileum and the colon and for the SB by trans-sectional imaging techniques.

The small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) has a higher diagnostic yield compared to the imaging techniques such as the magnetic resonance imaging with enterography (MRE) to detect mucosal lesions especially for the proximal part of the SB and might be more accurate in a treat-to-target strategy. SBCE and MRE are probably complementary, as MRE assesses transmural involvement, while SBCE allows a direct visualization of the mucosal surface of the entire SB. However, there is no recommendation regarding the use of SBCE during patient follow-up.

To investigate the impact of SBCE in a treat-to-target strategy in patients with CD.

An electronic search of the literature was conducted using PubMed and Cochrane library focusing on studies regarding SBCE in the tight monitoring of patients with CD. All articles containing information about SBCE in the context of treat-to-target strategy in patients with CD were included. Full-text articles were retrieved, reference lists were screened manually to identify additional studies.

Forty-seven articles were included in total. Twenty-two studies demonstrated the usefulness of SBCE on disease reclassification of patients suspected or diagnosed with CD, with a significant incremental diagnostic yield compared to other diagnostic modalities. Nine studies showed that mucosal healing can be evaluated by SBCE to monitor the effect of medical treatment. Seven studies demonstrated that SBCE could detect post-operative recurrence to a similar extent as ileocolonoscopy, and proximal SB lesions beyond the reach of the colonoscope in more than half of the patients.

This systematic review provided a global overview of the published studies assessing the use of SBCE in the tight monitoring of patients with CD. SBCE might be incorporated in the treat-to-target algorithm and could be useful for refining disease location and prognosis, assessing mucosal healing in patients under treatment, and monitoring patients in the post-operative setting.

Randomized controlled trials are required to confirm the reliability of SBCE in the treat-to-target algorithm of patients with CD. In addition, the development of pan-enteric video capsule endoscopy should allow to broaden its indications, all the more so as artificial intelligence is expected to help reduce the burden of capsule endoscopists by automatically detecting and classifying lesions.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: France

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abdolghaffari AH, Day AS, Mattar MC S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K, Jewell DP, Karban A, Loftus EV, Peña AS, Riddell RH, Sachar DB, Schreiber S, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, Vermeire S, Warren BF. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, D'Haens G, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Jewell DP, Rachmilewitz D, Sachar DB, Sandborn WJ, Sutherland LR. A simple classification of Crohn's disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:8-15. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785-1794. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1390] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1425] [Article Influence: 109.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rutgeerts P, Onette E, Vantrappen G, Geboes K, Broeckaert L, Talloen L. Crohn's disease of the stomach and duodenum: A clinical study with emphasis on the value of endoscopy and endoscopic biopsies. Endoscopy. 1980;12:288-294. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lazarev M, Huang C, Bitton A, Cho JH, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Proctor DD, Regueiro M, Rioux JD, Schumm PP, Taylor KD, Silverberg MS, Steinhart AH, Hutfless S, Brant SR. Relationship between proximal Crohn's disease location and disease behavior and surgery: a cross-sectional study of the IBD Genetics Consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:106-112. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 129] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wolters FL, Russel MG, Sijbrandij J, Ambergen T, Odes S, Riis L, Langholz E, Politi P, Qasim A, Koutroubakis I, Tsianos E, Vermeire S, Freitas J, van Zeijl G, Hoie O, Bernklev T, Beltrami M, Rodriguez D, Stockbrügger RW, Moum B. Phenotype at diagnosis predicts recurrence rates in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2006;55:1124-1130. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 165] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chow DK, Sung JJ, Wu JC, Tsoi KK, Leong RW, Chan FK. Upper gastrointestinal tract phenotype of Crohn's disease is associated with early surgery and further hospitalization. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:551-557. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kopylov U, Ben-Horin S, Seidman EG, Eliakim R. Video Capsule Endoscopy of the Small Bowel for Monitoring of Crohn's Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2726-2735. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, Tilg H, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cullen GJ, Daperno M, Kucharzik T, Rieder F, Almer S, Armuzzi A, Harbord M, Langhorst J, Sans M, Chowers Y, Fiorino G, Juillerat P, Mantzaris GJ, Rizzello F, Vavricka S, Gionchetti P; ECCO. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn's Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3-25. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1240] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1282] [Article Influence: 183.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Greener T, Klang E, Yablecovitch D, Lahat A, Neuman S, Levhar N, Avidan B, Yanai H, Dotan I, Chowers Y, Weiss B, Saibil F, Amitai MM, Ben-Horin S, Kopylov U, Eliakim R; Israeli IBD Research Nucleus (IIRN). The Impact of Magnetic Resonance Enterography and Capsule Endoscopy on the Re-classification of Disease in Patients with Known Crohn's Disease: A Prospective Israeli IBD Research Nucleus (IIRN) Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:525-531. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Modigliani R, Mary JY, Simon JF, Cortot A, Soule JC, Gendre JP, Rene E. Clinical, biological, and endoscopic picture of attacks of Crohn's disease. Evolution on prednisolone. Groupe d'Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:811-818. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Cellier C, Sahmoud T, Froguel E, Adenis A, Belaiche J, Bretagne JF, Florent C, Bouvry M, Mary JY, Modigliani R. Correlations between clinical activity, endoscopic severity, and biological parameters in colonic or ileocolonic Crohn's disease. A prospective multicentre study of 121 cases. The Groupe d'Etudes Thérapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives. Gut. 1994;35:231-235. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Diamond R, Rutgeerts P, Tang LK, Cornillie FJ, Sandborn WJ. Clinical disease activity, C-reactive protein normalisation and mucosal healing in Crohn's disease in the SONIC trial. Gut. 2014;63:88-95. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 347] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Bouguen G, Levesque BG, Feagan BG, Kavanaugh A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ. Treat to target: a proposed new paradigm for the management of Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1042-50.e2. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 198] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Bemelman W, Bryant RV, D'Haens G, Dotan I, Dubinsky M, Feagan B, Fiorino G, Gearry R, Krishnareddy S, Lakatos PL, Loftus EV, Marteau P, Munkholm P, Murdoch TB, Ordás I, Panaccione R, Riddell RH, Ruel J, Rubin DT, Samaan M, Siegel CA, Silverberg MS, Stoker J, Schreiber S, Travis S, Van Assche G, Danese S, Panes J, Bouguen G, O'Donnell S, Pariente B, Winer S, Hanauer S, Colombel JF. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-1338. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1160] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1250] [Article Influence: 138.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn's Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:481-517. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 705] [Article Influence: 117.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bourreille A, Ignjatovic A, Aabakken L, Loftus EV, Eliakim R, Pennazio M, Bouhnik Y, Seidman E, Keuchel M, Albert JG, Ardizzone S, Bar-Meir S, Bisschops R, Despott EJ, Fortun PF, Heuschkel R, Kammermeier J, Leighton JA, Mantzaris GJ, Moussata D, Lo S, Paulsen V, Panés J, Radford-Smith G, Reinisch W, Rondonotti E, Sanders DS, Swoger JM, Yamamoto H, Travis S, Colombel JF, Van Gossum A; World Organisation of Digestive Endoscopy (OMED) and the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). Role of small-bowel endoscopy in the management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: an international OMED-ECCO consensus. Endoscopy. 2009;41:618-637. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 263] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65-W94. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Gralnek IM, Defranchis R, Seidman E, Leighton JA, Legnani P, Lewis BS. Development of a capsule endoscopy scoring index for small bowel mucosal inflammatory change. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:146-154. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 285] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cotter J, Dias de Castro F, Magalhães J, Moreira MJ, Rosa B. Validation of the Lewis score for the evaluation of small-bowel Crohn's disease activity. Endoscopy. 2015;47:330-335. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rosa B, Moreira MJ, Rebelo A, Cotter J. Lewis Score: a useful clinical tool for patients with suspected Crohn's Disease submitted to capsule endoscopy. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:692-697. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gal E, Geller A, Fraser G, Levi Z, Niv Y. Assessment and validation of the new capsule endoscopy Crohn's disease activity index (CECDAI). Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1933-1937. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Niv Y, Ilani S, Levi Z, Hershkowitz M, Niv E, Fireman Z, O'Donnel S, O'Morain C, Eliakim R, Scapa E, Kalantzis N, Kalantzis C, Apostolopoulos P, Gal E. Validation of the Capsule Endoscopy Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CECDAI or Niv score): a multicenter prospective study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:21-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 114] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Koulaouzidis A, Douglas S, Plevris JN. Lewis score correlates more closely with fecal calprotectin than Capsule Endoscopy Crohn's Disease Activity Index. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:987-993. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yablecovitch D, Lahat A, Neuman S, Levhar N, Avidan B, Ben-Horin S, Eliakim R, Kopylov U. The Lewis score or the capsule endoscopy Crohn's disease activity index: which one is better for the assessment of small bowel inflammation in established Crohn's disease? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756283X17747780. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kopylov U, Klang E, Yablecovitch D, Lahat A, Avidan B, Neuman S, Levhar N, Greener T, Rozendorn N, Beytelman A, Yanai H, Dotan I, Chowers Y, Weiss B, Ben-Horin S, Amitai MM, Eliakim R; Israeli IBD research Nucleus (IIRN). Magnetic resonance enterography versus capsule endoscopy activity indices for quantification of small bowel inflammation in Crohn's disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:655-663. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | He C, Zhang J, Chen Z, Feng X, Luo Z, Wan T, Li A, Liu S, Ren Y. Relationships of capsule endoscopy Lewis score with clinical disease activity indices, C-reactive protein, and small bowel transit time in pediatric and adult patients with small bowel Crohn's disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7780. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chong AK, Taylor A, Miller A, Hennessy O, Connell W, Desmond P. Capsule endoscopy vs. push enteroscopy and enteroclysis in suspected small-bowel Crohn's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:255-261. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Efthymiou A, Viazis N, Vlachogiannakos J, Georgiadis D, Kalogeropoulos I, Mantzaris G, Karamanolis DG. Wireless capsule endoscopy versus enteroclysis in the diagnosis of small-bowel Crohn's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:866-871. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Carter D, Katz LH, Bardan E, Salomon E, Goldstein S, Ben Horin S, Kopylov U, Eliakim R. The accuracy of intestinal ultrasound compared with small bowel capsule endoscopy in assessment of suspected Crohn's disease in patients with negative ileocolonoscopy. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756284818765908. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Petruzziello C, Onali S, Calabrese E, Zorzi F, Ascolani M, Condino G, Lolli E, Naccarato P, Pallone F, Biancone L. Wireless capsule endoscopy and proximal small bowel lesions in Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3299-3304. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sorrentino D, Nguyen VQ. Clinically Significant Small Bowel Crohn's Disease Might Only be Detected by Capsule Endoscopy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1566-1574. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | González-Suárez B. Rodriguez S, Ricart E, Ordás I, Rimola J, Díaz-González Á, Romero C, de Miguel CR, Jáuregui A, Araujo IK, Ramirez A, Gallego M, Fernández-Esparrach G, Ginés Á, Sendino O, Llach J, Panés J. Comparison of Capsule Endoscopy and Magnetic Resonance Enterography for the Assessment of Small Bowel Lesions in Crohn's Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:775-780. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Xavier S, Cúrdia Gonçalves T, Dias de Castro F, Magalhães J, Rosa B, Moreira MJ, Cotter J. Perianal Crohn's disease - association with significant inflammatory activity in proximal small bowel segments. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:426-429. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Maunoury V, Savoye G, Bourreille A, Bouhnik Y, Jarry M, Sacher-Huvelin S, Ben Soussan E, Lerebours E, Galmiche JP, Colombel JF. Value of wireless capsule endoscopy in patients with indeterminate colitis (inflammatory bowel disease type unclassified). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:152-155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lopes S, Figueiredo P, Portela F, Freire P, Almeida N, Lérias C, Gouveia H, Leitão MC. Capsule endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease type unclassified and indeterminate colitis serologically negative. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1663-1668. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Long MD, Barnes E, Isaacs K, Morgan D, Herfarth HH. Impact of capsule endoscopy on management of inflammatory bowel disease: a single tertiary care center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1855-1862. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | De Bona M, Bellumat A, Cian E, Valiante F, Moschini A, De Boni M. Capsule endoscopy findings in patients with suspected Crohn's disease and biochemical markers of inflammation. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:331-335. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Mehdizadeh S, Chen GC, Barkodar L, Enayati PJ, Pirouz S, Yadegari M, Ippoliti A, Vasiliauskas EA, Lo SK, Papadakis KA. Capsule endoscopy in patients with Crohn's disease: diagnostic yield and safety. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:121-127. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, de Vega VM, Domènech E, Cabré E, Mañosa M, Boix J. Impact of capsule endoscopy findings in the management of Crohn's Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:411-414. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Urgesi R, Cianci R, Marmo C, Costamagna G, Riccioni ME. But how many misunderstood Crohn's disease are revealed "by chance" using Capsule Endoscopy in Chronic Recurrent OGIB? Experience of a Single Italian Center and long term follow-up. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:4553-4557. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Hall B, Holleran G, Chin JL, Smith S, Ryan B, Mahmud N, McNamara D. A prospective 52 week mucosal healing assessment of small bowel Crohn's disease as detected by capsule endoscopy. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1601-1609. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Shafran I, Burgunder P, DePanicis R, Fitch K, Hewit S, Abbott L. Evaluation of mucosal healing in Small Bowel Crohn’s disease treated with Certolizumab Pegol assessed by wireless capsule endoscopy. Clin Case Rep Rev. 2016;2. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Niv E, Fishman S, Kachman H, Arnon R, Dotan I. Sequential capsule endoscopy of the small bowel for follow-up of patients with known Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1616-1623. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kopylov U, Yablecovitch D, Lahat A, Neuman S, Levhar N, Greener T, Klang E, Rozendorn N, Amitai MM, Ben-Horin S, Eliakim R. Detection of Small Bowel Mucosal Healing and Deep Remission in Patients With Known Small Bowel Crohn's Disease Using Biomarkers, Capsule Endoscopy, and Imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1316-1323. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 104] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Aggarwal V, Day AS, Connor S, Leach ST, Brown G, Singh R, Friedman A, Zekry A, Craig PI. Role of capsule endoscopy and fecal biomarkers in small-bowel Crohn's disease to assess remission and predict relapse. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:1070-1078. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Mitselos IV, Katsanos KH, Tatsioni A, Skamnelos A, Eliakim R, Tsianos EV, Christodoulou DK. Association of clinical and inflammatory markers with small bowel capsule endoscopy findings in Crohn's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:861-867. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Beyls J, Kerremans R, Hiele M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:956-963. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | Bourreille A, Jarry M, D'Halluin PN, Ben-Soussan E, Maunoury V, Bulois P, Sacher-Huvelin S, Vahedy K, Lerebours E, Heresbach D, Bretagne JF, Colombel JF, Galmiche JP. Wireless capsule endoscopy versus ileocolonoscopy for the diagnosis of postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease: a prospective study. Gut. 2006;55:978-983. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 178] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Biancone L, Calabrese E, Petruzziello C, Onali S, Caruso A, Palmieri G, Sica GS, Pallone F. Wireless capsule endoscopy and small intestine contrast ultrasonography in recurrence of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1256-1265. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 71] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Pons Beltrán V, Nos P, Bastida G, Beltrán B, Argüello L, Aguas M, Rubín A, Pertejo V, Sala T. Evaluation of postsurgical recurrence in Crohn's disease: a new indication for capsule endoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:533-540. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Kono T, Hida N, Nogami K, Iimuro M, Ohda Y, Yokoyama Y, Kamikozuru K, Tozawa K, Kawai M, Ogawa T, Hori K, Ikeuchi H, Miwa H, Nakamura S, Matsumoto T. Prospective postsurgical capsule endoscopy in patients with Crohn's disease. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:88-98. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Hausmann J, Schmelz R, Walldorf J, Filmann N, Zeuzem S, Albert JG. Pan-intestinal capsule endoscopy in patients with postoperative Crohn's disease: a pilot study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:840-845. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Han ZM, Qiao WG, Ai XY, Li AM, Chen ZY, Feng XC, Zhang J, Wan TM, Xu ZM, Bai Y, Li MS, Liu SD, Zhi FC. Impact of capsule endoscopy on prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1489-1498. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Kusaka J, Shiga H, Kuroha M, Kimura T, Kakuta Y, Endo K, Kinouchi Y, Shimosegawa T. Residual Lesions on Capsule Endoscopy Is Associated with Postoperative Clinical Recurrence in Patients with Crohn's Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:768-774. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, Wilson DC, Turner D, Russell RK, Fell J, Ruemmele FM, Walters T, Sherlock M, Dubinsky M, Hyams JS. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1314-1321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 932] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1008] [Article Influence: 77.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Mao R, Tang RH, Qiu Y, Chen BL, Guo J, Zhang SH, Li XH, Feng R, He Y, Li ZP, Zeng ZR, Eliakim R, Ben-Horin S, Chen MH. Different clinical outcomes in Crohn's disease patients with esophagogastroduodenal, jejunal, and proximal ileal disease involvement: is L4 truly a single phenotype? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756284818777938. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Gionchetti P, Dignass A, Danese S, Magro Dias FJ, Rogler G, Lakatos PL, Adamina M, Ardizzone S, Buskens CJ, Sebastian S, Laureti S, Sampietro GM, Vucelic B, van der Woude CJ, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Maaser C, Portela F, Vavricka SR, Gomollón F; ECCO. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn's Disease 2016: Part 2: Surgical Management and Special Situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:135-149. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 451] [Article Influence: 64.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Leenhardt R, Li C, Koulaouzidis A, Cavallaro F, Cholet F, Eliakim AR, Fernandez-Urien I, Kopylov U, McAlindon M, Nemeth A, Plevris JN, Rahmi G, Rondonotti E, Saurin J-C, Tontini GE, Toth E, Yung DE, Marteau PR, Dray X. Sa1028 Terminology And Description Of Vascular Lesions In Small Bowel Capsule Endoscopy: An International Delphi Consensus Statement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:AB149–150. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Jensen MD, Brodersen JB, Kjeldsen J. Capsule endoscopy for the diagnosis and follow up of Crohn's disease: a comprehensive review of current status. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30:168-178. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Rokkas T, Papaxoinis K, Triantafyllou K, Pistiolas D, Ladas SD. Does purgative preparation influence the diagnostic yield of small bowel video capsule endoscopy?: A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:219-227. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Koulaouzidis A, Giannakou A, Yung DE, Dabos KJ, Plevris JN. Do prokinetics influence the completion rate in small-bowel capsule endoscopy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:1171-1185. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Kotwal VS, Attar BM, Gupta S, Agarwal R. Should bowel preparation, antifoaming agents, or prokinetics be used before video capsule endoscopy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:137-145. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Yung DE, Rondonotti E, Sykes C, Pennazio M, Plevris JN, Koulaouzidis A. Systematic review and meta-analysis: is bowel preparation still necessary in small bowel capsule endoscopy? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:979-993. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |