Published online Feb 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i7.2096

Peer-review started: July 6, 2014

First decision: July 21, 2014

Revised: July 29, 2014

Accepted: November 7, 2014

Article in press: November 11, 2014

Published online: February 21, 2015

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and tolerance of FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab treatment outcome as second-line treatment for metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

METHODS: Thirteen consecutive patients with metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma who were refractory to first-line therapy consisting of gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin-based first-line chemotherapy given intravenously via intra-arterial infusion were treated with FOLFIRI [irinotecan (180 mg/m²i.v. over 90 min) concurrently with folinic acid (400 mg/m²i.v. over 120 min) followed by fluorouracil (400 mg/m²i.v. bolus) then fluorouracil 2400 mg/m² intravenous infusion over 46 h] and bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) every 2 wk. Tumor response was evaluated by computed tomography scan every 4 cycles.

RESULTS: The best tumor responses using response evaluation criteria in solid tumor criteria were: complete response for 1 patient, partial response for 4 patients, and stable disease for 6 patients after 6 mo of follow-up. The response rate was 38.4% (95%CI: 12.5-89) and the disease control rate was 84.5% (95%CI: 42-100). Seven deaths occurred at the time of analysis, progression free survival was 8 mo (95%CI: 7-16), and median overall survival was 20 mo (95%CI: 8-48). No grade 4 toxic events were observed. Four grade 3 hematological toxicities and one grade 3 digestive toxicity occurred. An adaptive reduction in chemotherapy dosage was required in 2 patients due to hematological toxicity, and a delay in chemotherapy cycles was required for 3 patients.

CONCLUSION: FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab combination treatment showed promising efficacy and safety as second-line treatment for metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after failure of the first-line treatment of gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin chemotherapy.

Core tip: This retrospective study tests the efficacy of FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as second-line treatment for metastatic cholangiocarcinoma. We observed that this particular chemotherapy treatment gives good response rates and prolongs survival.

- Citation: Guion-Dusserre JF, Lorgis V, Vincent J, Bengrine L, Ghiringhelli F. FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as a second-line therapy for metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(7): 2096-2101

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i7/2096.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i7.2096

Biliary tract cancer is a collective term that groups together different tumors, including gallbladder tumor, cholangiocarcinoma, and ampulla of Vater tumor with a relative frequency of 41%, 42%, and 17%, respectively[1-3]. These tumors arise from the transformation of intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile duct epithelial cells. Cholangiocarcinoma is divided into 3 categories based on anatomic location of origin within the biliary system: intrahepatic, hilar, and distal extrahepatic canals. Upon epidemiological study, hilar tumors were more frequent; however intrahepatic tumor incidence is rising. The median survival for biliary tract cancer is poor, but very different for each subtype. Gallbladder cancer is more frequent in females, with a survival around 6-9 mo, while cholangiocarcinoma is more frequent in males and is also more aggressive, with a poor survival time of around 4-6 mo without therapy[1]. The only curative treatment is the complete surgical removal of the tumor. When the tumor can be removed by surgery, the 5 year survival rate is around 30%. When the tumor is not resectable, the standard treatment is systemic chemotherapy[4,5]. Recently, 2 phase III trials demonstrated that chemotherapy combining gemcitabine and platinum derivatives could be considered as a standard of care for unresectable cholangiocarcinoma and seems to improve overall survival, with a median survival of 12 mo for the cisplatin plus gemcitabine regimen[6] and 9.5 mo for the oxaliplatin plus gemcitabine regimen[7].

While the choice for first-line chemotherapy is largely agreed upon, second-line treatment is still a topic of discussion[8,9]. Very few studies of second-line chemotherapy for advanced biliary tract cancer have been reported, with all such studies pooling together patients with different types of biliary tract cancer with different prognoses. The role of targeted therapies is also under investigation in some trials[9,10]. In this study, we report on the tolerance and efficacy of the off-label usage of FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab combination as a second-line treatment in metastatic cholangiocarcinoma after failure of the gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin regimen.

This retrospective study was conducted at the Georges Francois Leclerc Center from January 2009 to January 2014. The proposal of the off-label usage of FOLFIRI bevacizumab was evaluated and validated by the local multidisciplinary staff. Informed consent was obtained from each participant and follow-up was prospectively registered. We proposed this treatment for patients with advanced biliary tract carcinoma who met the following criteria: (1) received gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin combination therapy as a first-line treatment administrated intravenously or by intra-arterial injection; (2) underwent progression during the first-line therapy; (3) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-2; and (4) had adequate bone marrow function (white blood cell count > 3000/mm3, hemoglobin > 9.0 g/dL, and platelet count > 100000/mm3), liver function [total bilirubin < 3 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) and aspartate/alanine transaminases < 5 times the ULN], and renal function (creatinine < 1.2 mg/dL or creatinine clearance > 50 mL/min). In patients with obstructive jaundice, total serum bilirubin was required to be within 3 times the ULN after biliary drainage. Exclusion criteria included: uncontrolled infection, uncontrolled massive pleural effusion or massive ascites, active ulcer of the gastrointestinal tract, pregnancy/lactation, a history of drug hypersensitivity, active concomitant malignancy, and concurrent severe medical conditions.

The FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab regimen consists of bevacizumab injection (5 mg/kg) followed by irinotecan (180 mg/m²i.v. over 90 min) concurrently with folinic acid (400 mg/m²i.v. over 120 min), followed by fluorouracil (400 mg/m²i.v. bolus) then fluorouracil (2400 mg/m² intravenous infusion over 46 h). Dose reductions were based on adverse events that were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0. Treatment was temporarily suspended in cases of grade 3/4 hematological toxicity or grade 2 or higher non-hematological toxicity. After toxicity was reduced to grade 1 or below, treatment was restarted at a lower dose. The treatment was suspended if the patients continued to experience further toxicity. Dose re-escalation was not applied in this setting. Treatment continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patient refusal.

Pretreatment evaluation included physical examination, complete blood cell counts, blood chemistry, tumor marker level (carbohydrate antigen, CA 19-9), and thorax abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT)-scan within 15 d of starting chemotherapy. Tumor responses were determined by RECIST criteria[11]. Complete blood cell counts and serum chemistry (including liver and renal function) were performed at least every 2 wk, with tumor assessment via thorax abdominal and pelvic CT-scan and CA19.9 dosage performed every four cycles (8 wk). Toxicity was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0.

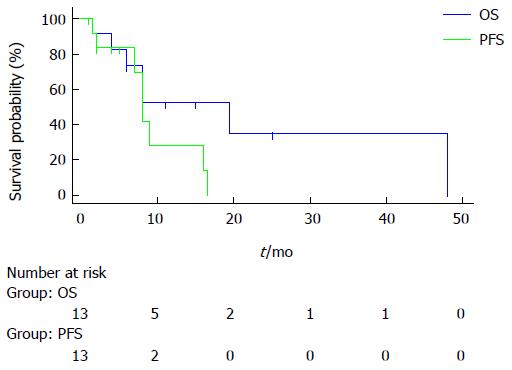

Efficacy analysis was performed according to the intention to-treat principle. Patients were considered assessable for response if they were eligible, had measurable disease, and had received at least one cycle of chemotherapy. In the analysis of survival and subsequent treatment, all patients were followed until death or lost to follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. PFS was calculated from the start of FOLFIRI bevacizumab therapy to the date of disease progression, and OS was calculated from the start of FOLFIRI bevacizumab therapy to the date of death. Analysis was carried out using MEDCALC software (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium).

Between January 2009 and January 2014, a total of 13 patients were treated at the Department of Medical Oncology, Georges-Francois Leclerc Cancer Center, Dijon, France by FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab combination treatment for metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after failure of first-line gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin combination. Demographic details of the patients included in the study are shown in Table 1. All 13 patients were assessable for toxicity, survival, and radiological response using RECIST criteria.

| Characteristics | Patients (n) |

| Median age (range) (yr) | 60 (39-72) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 6 |

| Female | 7 |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 3 |

| 1 | 8 |

| 2 | 2 |

| Median CA 19-9 level (range) (ng/mL) | 73 (2-4472) |

| Previous chemotherapy | |

| Intravenous gemcitabine oxaliplatin | 13 |

| Intra-arterial gemcitabine oxaliplatin | 5 |

| Tumor limiting the liver | |

| Yes | 4 |

| No | 9 |

A total of 128 cycles of chemotherapy were administered (median 6; range: 2-22). Hematological and non-hematological toxicities of grades 1-4 are listed in Table 2. No grades 4 toxic events were observed. Four grade 3 hematological toxicities and one grade 3 digestive toxicity occurred. An adaptive reduction in chemotherapy dosage was required in 2 patients because of hematological toxicity and a delay in chemotherapy cycles was required for 3 patients. The most frequent events were neutropenia in 7 patients, anemia in 5 patients, thrombocytopenia in 6 patients, and diarrhea in 5 patients. No febrile neutropenia were observed.

| NCI-CTC grade | ||

| All grades | Severe1 | |

| Hematological | ||

| Anemia | 5 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 7 | 3 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 | 2 |

| Non hematological | ||

| Nausea/vomiting | 6 | 0 |

| Mucositis | 1 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 5 | 2 |

| Infection | 0 | 0 |

| Nose bleeding | 2 | 0 |

| High blood pressure | 2 | 0 |

Concerning bevacizumab-induced toxicity, no interruption to treatment was required, and no bowel perforation, brain bleeding, or digestive bleeding was observed. Tolerance of bevacizumab was good, with only 2 cases of grade 2 hypertensions and epistaxis. At the time of analysis, with a median follow-up of 25 mo (range: 6-48 mo), a total of 7 patients (83%) had died, all due to disease progression.

All included patients were previously treated with systemic chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin as a first-line treatment, which failed. In addition 4 patients received hepatic intra-arterial chemotherapy by gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin as a second-line treatment. All patients are metastatic at the start of FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab treatment. According to the RECIST criteria, among the 13 assessable patients we noted one complete response, 4 partial responses, 6 stable diseases for at least 6 mo, and two progressions. The response rate was 38.4% (95%CI: 12.5-89) and the disease control rate was 84.5% (95%CI: 42-100). At 2 mo, the CA 19.9 level decreased in all patients (mean level 518 ± 1254 vs 173 ± 364, P = 0.04 Wilcoxon test). On June 2014, 7 deaths occurred, PFS was 8 mo (95%CI: 7-16), and median OS was 20 mo (95%CI: 8-48). Figure 1 shows PFS and OS curves.

The treatment of metastatic biliary tract cancer currently remains a challenging question. Recently, the combination treatment of cisplatin and gemcitabine became the standard of care in first-line therapy based on the phase III randomized data UK NCRN ABC-02 study[6]. This study demonstrated an overall survival advantage for cisplatin plus gemcitabine combination vs gemcitabine alone (11.7 mo vs 8.1 mo, HR = 0.64, 95%CI: 0.52-0.80; P < 0.001). Similar results were observed in a Japanese randomized phase II study (BT22) using the same treatment regimen, with a median survival of 11.2 mo with cisplatin and gemcitabine[12]. In France, most oncologists prefer the gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin combination due to its easier usage and reduced toxicity[13,14]. Recently, the phase II BINGO study observed that gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin had an overall survival of 12 mo, similar to the gemcitabine and cisplatin combination[15], thereby confirming that gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin could be a valuable first-line regimen.

In contrast, to date there is no phase III evidence supporting the use of second-line chemotherapy after failure of first-line chemotherapy for metastatic biliary tract cancers. In the UK NCRN ABC-02 trial[6], 15% were treated with second-line chemotherapy[16]. In contrast, 63 of the 84 patients (75%) included in the Japanese BT22 trial[12] received second-line chemotherapy, essentially with S1 chemotherapy. Despite this difference in the rate of second-line chemotherapy, similar survival was observed in the 2 studies, thus questioning the benefit of second-line chemotherapy. A recent multicentric retrospective Italian study reported the evolution of 300 patients receiving second-line chemotherapy for biliary tract cancer in a cohort of 811 patients that previously received first-line therapy. In this study, only 4% of partial responses and 30% of disease stabilizations were observed, giving a median PFS of 3.2 mo[17]. In the ASCO 2014 meeting, the AGEO group reported the efficacy of second-line therapy for biliary tract carcinoma in patients previously treated with gemcitabine and platinum combination[18]. They observed that the usage of second-line therapy is associated with disease control in half of the patients who previously received gemcitabine plus platinum as a first-line treatment. When looking at chemotherapy regimens, were was no difference in term of PFS or OS for the usage of 5-fluorouracil (5FU) monotherapy or association of 5FU plus cisplatin or irinotecan. However, in another study irinotecan was reported to have some efficacy in patients previously treated with gemcitabine and platinum, suggesting that this treatment is effective in second-line therapy[19].

Few studies have tested the efficacy of targeted therapies in biliary tract cancer. The mTOR inhibitor everolimus was tested in second-line therapy in a recent phase II trial with PFS around 3 and an 8 mo of OS with acceptable toxicity[20]. Anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)1 and HER2 therapies were also tested. Cetuximab failed to demonstrate efficacy in first-line biliary tract cancer[15]. Erlotinib was tested in combination with gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin and did not improve PFS or OS[7]. Moreover, combination of erlotinib plus sorafenib[21] or monotherapy with lapatinib failed to demonstrate clinical efficacy[22]. Sunitinib was also tested in a phase II study as a second-line regimen and demonstrated marginal efficacy and significant toxicity[23].

Bevacizumab was tested in first-line treatment in combination with erlotinib in a phase II trial and gave an interesting control rate and OS of about 10 mo[24]. In addition, a phase II study of bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin gave a major response rate of 44% in first-line therapy[25] compared with 20% with gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin alone, thus suggesting the efficacy of bevacizumab. Based on all these data, we hypothesize that bevacizumab associated with 5FU plus irinotecan may have some efficacy in biliary tract cancer treatment. A case report underlined the high efficacy of bevacizumab plus panitumumab combination treatment[26].

We decide in our institute to propose off-label usage of FOLFIRI bevacizumab for patients with cholangiocarcinoma that progressed after first-line gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin usage. This off-label usage was validated after multidisciplinary staff consultation, and all patients give written consent to this off-label drug usage. We also prospectively examined the efficacy and toxicity of the protocol for each patient. Limitations of this study were its retrospective nature, non-comparative design, and low number of patients. However, very few prospective studies have been conducted to assess second-line efficacy for cholangiocarcinoma, and no comparative study has been conducted in this field. Although our study was retrospective and included only a limited number of patients, we selected a very homogeneous population of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, all previously treated with an up-to-date first-line chemotherapy regimen. In addition, this rate of disease control and significant median time to progression for a disease with a very poor prognosis led to the conclusion that such chemotherapy regimens have a significant clinical impact.

In conclusion, FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab combination therapy showed anti-tumor efficacy and safety as a second-line treatment for metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma refractory to gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin first-line chemotherapy. Larger scale prospective trials should be conducted to confirm this conclusion.

First-line chemotherapy for metastatic biliary tract cancer consists of gemcitabine plus platinum regime. However, the strategy for second-line therapy remains an unanswered question.

Few studies focus on the efficacy of second-line therapy for metastatic biliary tract cancer. Based on previous studies, patients were treated with a combination of FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab.

Using the RECIST criteria, the responses were: complete response for 1 patient, partial response for 4 patients, and stable disease for 5 patients at 6 mo. The median overall survival and time to progression were 8 and 20 mo, respectively.

This study underlines the possible efficacy of bevacizumab plus FOLFIRI as a second-line treatment for metastatic cholangiocarcinoma.

This is a pilot study that provides a new strategy for the second-line treatment of advanced cholangiocarcinoma. The clinical outcome is acceptable and may give new hope in cases of first-line treatment failure in patients suffering cholangiocarcinoma.

P- Reviewer: Araujo A, Chung FT, Hsu CP S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Eckel F, Schmid RM. Chemotherapy in advanced biliary tract carcinoma: a pooled analysis of clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:896-902. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 337] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Takada T, Amano H, Yasuda H, Nimura Y, Matsushiro T, Kato H, Nagakawa T, Nakayama T. Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma? A phase III multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:1685-1695. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 426] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Henson DE, Albores-Saavedra J, Corle D. Carcinoma of the gallbladder. Histologic types, stage of disease, grade, and survival rates. Cancer. 1992;70:1493-1497. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Glimelius B, Hoffman K, Sjödén PO, Jacobsson G, Sellström H, Enander LK, Linné T, Svensson C. Chemotherapy improves survival and quality of life in advanced pancreatic and biliary cancer. Ann Oncol. 1996;7:593-600. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Thongprasert S. The role of chemotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2005;16 Suppl 2:ii93-ii96. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 111] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273-1281. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2617] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2746] [Article Influence: 196.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee J, Park SH, Chang HM, Kim JS, Choi HJ, Lee MA, Jang JS, Jeung HC, Kang JH, Lee HW. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin with or without erlotinib in advanced biliary-tract cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:181-188. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 323] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lamarca A, Hubner RA, David Ryder W, Valle JW. Second-line chemotherapy in advanced biliary cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:2328-2338. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 231] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cereda S, Belli C, Rognone A, Mazza E, Reni M. Second-line therapy in advanced biliary tract cancer: what should be the standard? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:368-374. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ramírez-Merino N, Aix SP, Cortés-Funes H. Chemotherapy for cholangiocarcinoma: An update. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;5:171-176. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 107] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-247. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15860] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18959] [Article Influence: 1263.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Okusaka T, Nakachi K, Fukutomi A, Mizuno N, Ohkawa S, Funakoshi A, Nagino M, Kondo S, Nagaoka S, Funai J. Gemcitabine alone or in combination with cisplatin in patients with biliary tract cancer: a comparative multicentre study in Japan. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:469-474. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 462] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 504] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pracht M, Le Roux G, Sulpice L, Mesbah H, Manfredi S, Audrain O, Boudjema K, Raoul JL, Boucher E. Chemotherapy for inoperable advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: retrospective analysis of 78 cases in a single center over four years. Chemotherapy. 2012;58:134-141. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mir O, Coriat R, Dhooge M, Perkins G, Boudou-Rouquette P, Brezault C, Ropert S, Durand JP, Chaussade S, Goldwasser F. Feasibility of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with advanced biliary tract carcinoma and a performance status of 2. Anticancer Drugs. 2012;23:739-744. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Malka D, Cervera P, Foulon S, Trarbach T, de la Fouchardière C, Boucher E, Fartoux L, Faivre S, Blanc JF, Viret F. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin with or without cetuximab in advanced biliary-tract cancer (BINGO): a randomised, open-label, non-comparative phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:819-828. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 275] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bridgewater J, Palmer D, Cunningham D, Iveson T, Gillmore R, Waters J, Harrison M, Wasan H, Corrie P, Valle J. Outcome of second-line chemotherapy for biliary tract cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1511. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fornaro L, Cereda S, Aprile G, Di Girolamo S, Santini D, Silvestris N, Lonardi S, Leone F, Milella M, Vivaldi C. Multivariate prognostic factors analysis for second-line chemotherapy in advanced biliary tract cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2165-2169. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Brieau B, Dahan L, De Rycke Y, Boussaha T, Vasseur P, Tougeron D, Lecomte T, Coriat R, Bachet JB, Claudez P. Second-line chemotherapy for advanced biliary tract cancer after failure of gemcitabine plus platinum: Results of an AGEO multicenter retrospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:5s. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Normile D. Radiation safety. Accelerator leak halts Japanese physics experiments. Science. 2013;340:1155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Buzzoni R, Pusceddu S, Bajetta E, De Braud F, Platania M, Iannacone C, Cantore M, Mambrini A, Bertolini A, Alabiso O. Activity and safety of RAD001 (everolimus) in patients affected by biliary tract cancer progressing after prior chemotherapy: a phase II ITMO study. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1597-1603. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | El-Khoueiry AB, Rankin C, Siegel AB, Iqbal S, Gong IY, Micetich KC, Kayaleh OR, Lenz HJ, Blanke CD. S0941: a phase 2 SWOG study of sorafenib and erlotinib in patients with advanced gallbladder carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:882-887. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Peck J, Wei L, Zalupski M, O’Neil B, Villalona Calero M, Bekaii-Saab T. HER2/neu may not be an interesting target in biliary cancers: results of an early phase II study with lapatinib. Oncology. 2012;82:175-179. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yi JH, Thongprasert S, Lee J, Doval DC, Park SH, Park JO, Park YS, Kang WK, Lim HY. A phase II study of sunitinib as a second-line treatment in advanced biliary tract carcinoma: a multicentre, multinational study. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:196-201. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lubner SJ, Mahoney MR, Kolesar JL, Loconte NK, Kim GP, Pitot HC, Philip PA, Picus J, Yong WP, Horvath L. Report of a multicenter phase II trial testing a combination of biweekly bevacizumab and daily erlotinib in patients with unresectable biliary cancer: a phase II Consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3491-3497. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 192] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhu AX, Meyerhardt JA, Blaszkowsky LS, Kambadakone AR, Muzikansky A, Zheng H, Clark JW, Abrams TA, Chan JA, Enzinger PC. Efficacy and safety of gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab in advanced biliary-tract cancers and correlation of changes in 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET with clinical outcome: a phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:48-54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 214] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Riley E, Carloss H. Dramatic response to panitumumab and bevacizumab in metastatic gallbladder carcinoma. Oncologist. 2011;16:e1-e2. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |