Published online Jul 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.8184

Peer-review started: December 1, 2014

First decision: February 10, 2015

Revised: March 18, 2015

Accepted: April 3, 2015

Article in press: April 3, 2015

Published online: July 14, 2015

AIM: To investigate the impact of JetPrep cleansing on adenoma detection rates.

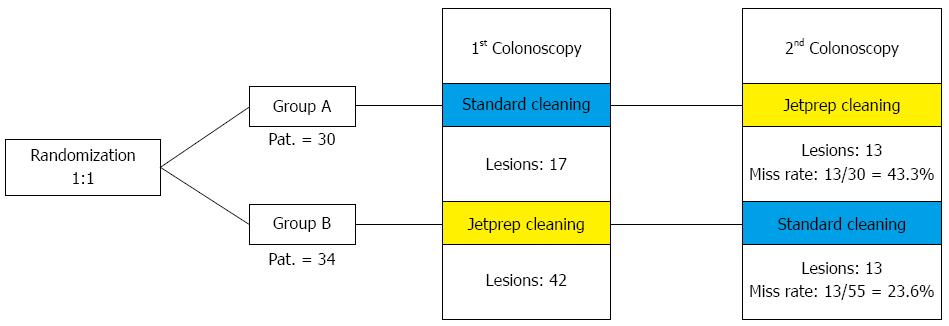

METHODS: In this prospective, randomized, crossover trial, patients were blindly randomized to an intervention arm or a control arm. In accordance with the risk profile for the development of colorectal carcinoma, the study participants were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups. Individuals with just one criterion (age > 70 years, adenoma in medical history, and first-degree relative with colorectal cancer) were regarded as high-risk patients. Bowel preparation was performed in a standardized manner one day before the procedure. Participants in the intervention arm underwent an initial colonoscopy with standard bowel cleansing using a 250-mL syringe followed by a second colonoscopy that included irrigation by the use of the JetPrep cleansing system. The reverse sequence was used in the control arm. The study participants were divided into a high-risk group and a low-risk group according to their respective risk profiles for the development of colorectal carcinoma.

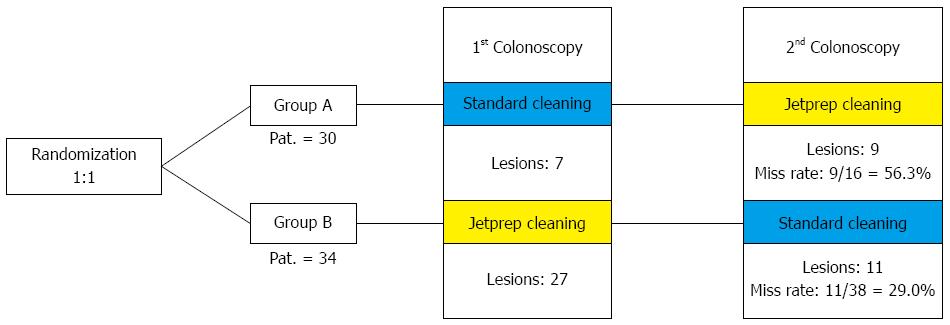

RESULTS: A total of 64 patients (34 men and 30 women) were included in the study; 22 were included in the high-risk group. After randomization, 30 patients were assigned to the control group (group A) and 34 to the intervention group (group B). The average Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score was 5.15 ± 2.04. The withdrawal time needed for the first step was significantly longer in group A using the JetPrep system (9.41 ± 3.34 min) compared to group B (7.5 ± 1.92 min). A total of 163 polyps were discovered in 64 study participants who underwent both investigation steps. In group A, 49.4% of the polyps were detected during the step of standard bowel cleansing while the miss rate constituted 50.7%. Group B underwent cleansing with the JetPrep system during the first examination step, and as many as 73.9% of polyps were identified during this step. Thus, the miss rate in group B was a mere 26.1% (P < 0.001). When considering only the right side of the colon, the miss rate in group A during the first examination was 60.6%, in contrast to a miss rate of 26.4% in group B (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: JetPrep is recommended for use during colonoscopy because a better prepared bowel enables a better adenoma detection, particularly in the proximal colon.

Core tip: Stool tends to hinder visibility during colonoscopy, and its presence therefore increases the risk that lesions will be overlooked. The JetPrep system is an irrigation system that was designed for intraprocedural colon cleansing. The aim of this randomized, prospective study was to investigate the impact of JetPrep cleansing on detection rates of adenomas. The JetPrep system enabled better cleansing of the colon, which increased the detection of polyps throughout the entire colon and especially on its right side (P < 0.001). Based on the results of this study, the JetPrep flushing device may be broadly recommended for use during screening colonoscopy to improve bowel preparation and to increase polyp detection rates.

- Citation: Hoffman A, Murthy S, Pompetzki L, Rey JW, Goetz M, Tresch A, Galle PR, Kiesslich R. Intraprocedural bowel cleansing with the JetPrep cleansing system improves adenoma detection. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(26): 8184-8194

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i26/8184.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.8184

Colonoscopy is considered the gold standard for colon cancer screening and the removal of precancerous lesions of the colon. However, colonoscopy appears to be less effective at preventing disease (and therefore preventing mortality) when used to examine right-sided colonic lesions vs those that develop on the left side[1-3]. Even in cases in which the bowel was properly prepared by the patient prior to colonoscopy, stool remnants and mucus residues can hinder visibility during the procedure. This reduced visibility may result in premalignant or malignant lesions being overlooked during screening colonoscopy and might therefore increase the risk of interval cancers, as it has been shown that better visibility during the procedure (as a result of optimal preparation of the colon) increases the likelihood of discovering precancerous lesions in the colon[1-3]. This may further reduce the incidence of colon cancer and the mortality associated with it. However, despite that there are numerous available options for bowel cleansing and laxative regimens, suboptimal colonic preparation is observed in approximately 20% of all patients[4-8]. Suboptimal bowel preparation leads to reduced cecal intubation rates, longer examination times, and lower polyp detection rates[4-8].

Furthermore, only a few endoscopic options exist that can improve bowel cleansing during colonoscopy. One such example is the irrigation of the bowel using either a water-filled syringe or a peristaltic pump placed through the working channel of the endoscope; unfortunately, this method rarely results in adequate improvements to visibility.

Many novel techniques have been proposed to improve the visualization of the proximal aspects of colonic folds and flexures, with the collective goal of increasing the rate of adenoma detection. However, the majority of these techniques still require further evaluation before being translated into a clinical setting[9,10].

Targeted irrigation of the colon by the use of cleansing systems may serve as one important alternative that can enhance adenoma detection rates and improve the overall quality of colonoscopy. The JetPrep system (MedJet Ltd. Tel Aviv, Israel) is a newly introduced irrigation system designed for intraprocedural colon cleansing. The JetPrep operates in a similar manner to a showerhead and can be introduced into the colon through the working channel of an endoscope. Earlier studies have demonstrated significant benefits associated with using JetPrep cleansing compared to standard cleansing (e.g., fixing a 50-mL syringe on the working channel).

Therefore, the aim of the current randomized, prospective study was to investigate the impact of JetPrep cleansing on the detection rates of adenomas and serrated lesions, particularly on the right side of the colon[11-13].

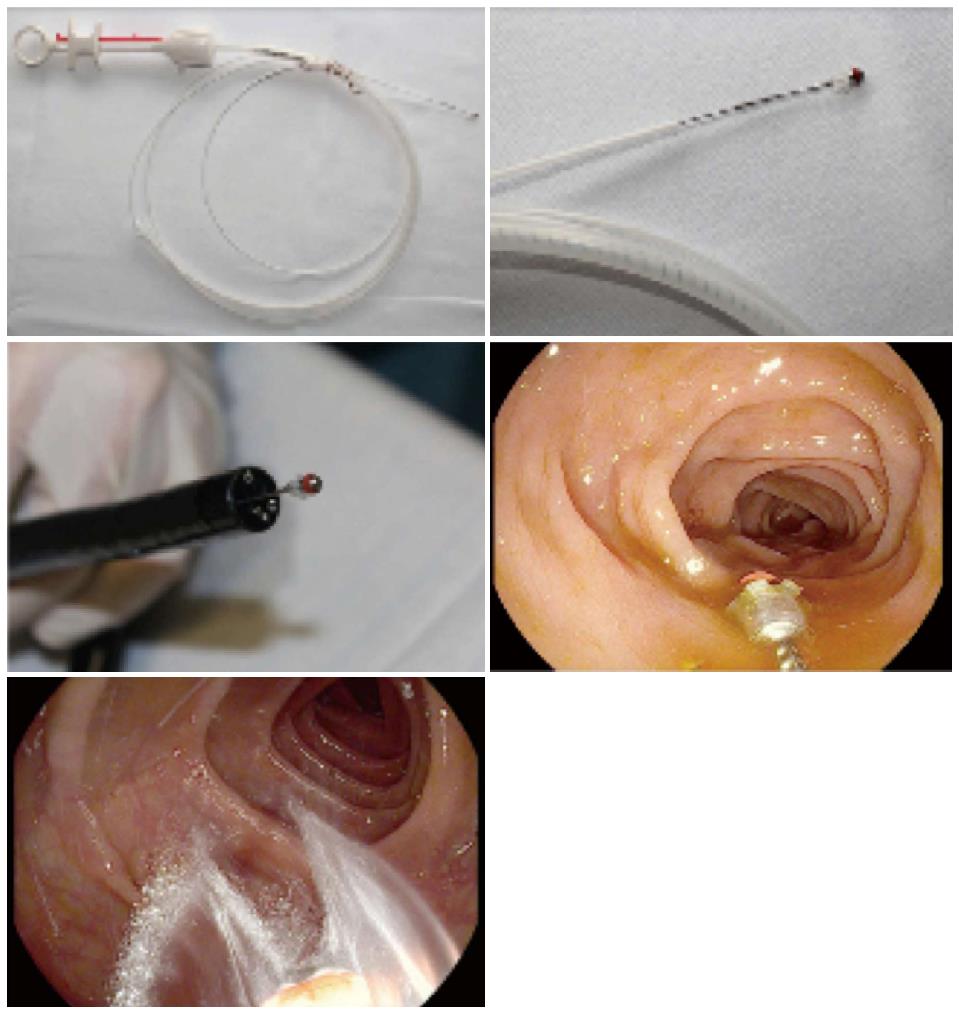

The JetPrep device (MedJet Ltd. Tel Aviv, Israel) is a CE-certified [39000162CN], sterile, disposable, catheter-based product. It is introduced into the colon through the working channel (3.8 mm) of an endoscope to cleanse the mucosal surface during colonoscopy. To ensure simultaneous suctioning of fluid and stool while the JetPrep device is in the working channel, the spray nozzle at the tip of the device can be pushed out of the working channel by 1-2 cm with a single movement of the hand. This prevents blockage of the working channel. The spray nozzle itself is made of silicone, which minimizes the risk of traumatic injury to the colonic mucosa (Figure 1).

Sterile saline can be introduced into the bowel through the spray nozzle of the device using a commercially available pump. This allows the mucosa to be irrigated with a broad spray of liquid rather than a narrow stream and facilitates the cleaning of the margins of the field of vision (Figure 1).

In preliminary feasibility studies, the JetPrep system proved to be an effective and safe method for cleansing the bowel, although the withdrawal time of the system (11.4 min) reflects that the cleansing of a suboptimally prepared colon can be time-consuming[14,15].

We performed standard high-definition colonoscopies to investigate the efficacy of the JetPrep cleansing system (intervention arm) for improving the detection of adenomas and serrated lesions in the colon compared to standard cleansing procedures that use a 250-mL syringe attached to the working channel of the endoscope (control arm).

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Mainz. Our subjects included a cohort of 50-year-old patients who were referred for either screening or surveillance colonoscopy (after previous polypectomy) at the interdisciplinary endoscopy department of the University Hospital. All patients gave consent to participate in the study. Table 1 lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Bowel preparation was performed in a standardized manner before the procedure via a Moviprep (polyethylene glycol solution, Norgine, Netherland) regimen that consisted of either the consumption of 1 liter of Moviprep during the evening before the investigation and another liter in the morning before the investigation or of 2 litres during the evening before the investigation. In the latter case, each liter of Moviprep had to be taken within the same 1 to 2 h span and the drinking of an additional liter of any clear liquid was required at this time.

| Inclusion criteria |

| All patients ≥ 50 yr of age who reported for a screening or surveillance colonoscopy and had a history of removed adenomas were included in the study. |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Patients who were unable to sign the informed consent form |

| Patients who had undergone previous (partial) resection of the large bowel, except for appendectomy |

| Patients with known or pre-existing colorectal carcinoma |

| Patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease |

| Patients with known FAP or HNPCC syndromes in the family |

| Patients with a Quick score < 50%, pTT > 50 s, or thrombocytes < 50000/μL who had received no specific measures for the improvement of their coagulation (FFP, TK) before the examination |

| Patients suffering from a severe underlying disease (ASA > II°) |

| Patients who were determined to have a cleanliness score of 3 on the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale for the proximal portion of the colon during the examination |

| Patients in whom a complete colonoscopy could not be performed in the first or second step of the investigation |

| Patients in whom the first step of the investigation took ≥ 45 min |

The study participants were divided into a high-risk and a low-risk group in accordance with the risk profile for the development of colorectal carcinoma. Individuals with just one criterion (age > 70 years, adenoma in medical history, first-degree relative with colorectal cancer) were regarded as high-risk patients. Patients were blindly randomized into either the intervention arm or the control arm. The group that the patient was classified into was announced only after reaching the cecum.

The patients in the control group (group A) underwent an initial colonoscopy that included standard intraprocedural bowel cleansing (250 mL syringe), which was immediately followed by a second colonoscopy (in a standardized crossover fashion) that included irrigation by the use of the JetPrep cleansing system. The reverse sequence was used for the patients in the intervention group (group B).

All procedures included in this study were conducted by two separate investigators (Kiesslich R, Murthy S) who were each experienced in performing colonoscopies using Pentax high-definition endoscopes (Pentax EPKi, Pentax 90i, Pentax Europe).

The length of time that it took to conduct each investigation was measured using a stopwatch and recorded. In agreement with previously published results, the minimal withdrawal time for the detection of polyps per investigation step was set to 6 min; the time was stopped during endoscopic interventions such as polypectomy[16]. During the endoscopic investigation, the patients were sedated with either 1% propofol (Disoprivan, AstraZenca Zug, Switzerland) or midazolam (Dormicum, Roche Pharma AG Basel, Switzerland).

Fluid stool residues were suctioned when inserting the endoscope into the cecum, and the baseline value for bowel preparation was determined using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale to better objectify the degree of subsequent cleansing (Table 2).

| 0 = Unprepared colon segment. Due to solid stool that cannot be cleared, the mucosa cannot be observed |

| 1 = Some portions of the mucosa of the colon segment can be observed, but other areas are covered by residual staining consisting of residual stool or opaque fluid |

| 2 = Minor amount of residual staining. No stool fragments or small quantities of opaque fluid, but the mucosal surface of the colon segment can be observed well |

| 3 = The entire mucosa of the colon segment can be observed well and has no residual staining |

Based on an examination of the right colon, patients who were found to have a Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) of 3 were excluded from intraprocedural bowel prep cleansing.

In both investigation groups, the removal of stool deposits from the mucosa was performed only when withdrawing from the cecum.

The cleansing time was included when calculating the withdrawal time; the amount of time taken to set up the JetPrep device was recorded separately and did not influence the withdrawal time. All polyps were removed during withdrawal with either a biopsy forceps (< 5 mm) or with an electric loop (> 5 mm), except for small (< 5 mm) hyperplastic polyps of the rectum and the sigmoid colon that presented no evident malignant potential according to the pit pattern classification. Every polyp was graded before removal according to both pit pattern and the Paris classification. The precise quantity of water required for cleansing was recorded for both examination arms. The Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) was determined after both the first and second cleansing steps[17]. The proximal portion of the colon was then examined, and all patients who were considered to have a cleanliness score of 3 on the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale were excluded.

After the investigation, all patients were monitored in a standardized manner and were discharged the same day. The study participants were either called the following day or were questioned at the ward about the occurrence of adverse events.

Patient data were recorded on a case report form, and relevant details concerning medical history were included.

During the procedure, the time points corresponding to the commencement and conclusion of each examination step were recorded in addition to the length of time that was spent during cleansing and intervention. Every polyp that was discovered during the investigation was registered in a table and the respective histological findings were subsequently recorded.

For both intervention arms, the primary endpoint of the study was the percentage miss rate of adenomas and serrated lesions on the right side of the colon during the first examination step. The secondary endpoints of the study are summarized in Table 3.

| Miss rate for the entire colon |

| Polyp miss rates and detection rates for the entire colon and the right side of the colon |

| Colon cleanliness after JetPrep and standard cleaning (based on the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale) |

| Rate of adverse events resulting from the use of JetPrep |

Case numbers were calculated based on previously published studies concerning tandem colonoscopy, which reported miss rates of 27%-37% for adenomas on the right side of the colon under standard conditions[12].

Assuming that irrigation with the JetPrep flushing device would reveal not only small adenomas but also adenomas coated with mucus and flat serrated ones, we presumed an absolute risk reduction of ≥ 30% in the present study, with an effective miss rate of 40% in the control group and 10% in the intervention group. We determined that the detection of at least 64 lesions was necessary to achieve a statistically significant absolute risk reduction when employing a one-sided Fisher’s exact test for statistical analysis.

Because the majority of previous studies have assumed an average of one neoplastic lesion per patient, the value described above can be considered equivalent to a sample size of 64 patients or 32 patients per study arm. The χ2 test was used to compare the categorical variables of the secondary endpoints amongst the various groups. Version 18.0 of the SPSS program was used to evaluate the data.

A total of 73 patients were recruited for the study between March and July of 2012. Six patients were subsequently excluded from the study as a result of having BBPS scores of 3 in the ascending colon. It was not possible to perform a complete colonoscopy in one of the study subjects due to the presence of adhesions.

Two additional patients had to be excluded after the first step of the study due to the respective reasons of an excessively long examination time in one and the presence of stool residues in the bowel that could not be suctioned through the working channel of the endoscope (and thus interfered with the examination) in the other.

A final count of 64 patients (34 men and 30 women) were included in the study, of whom 22 had at least one risk factor for developing colorectal carcinoma (e.g., a first-degree relative with colorectal cancer, a positive medical history for adenoma, or an age > 70 years; Table 4). Thus, 42 patients were assigned to the low-risk group. Following our randomization process a total of 30 patients were assigned to the control group (group A) and 34 to the intervention group (group B).

| Original cohort of patients | n = 73 |

| Dropouts | 9/73 (12.3%) |

| Number of included patients | 64/73 (87.7%) |

| Group stratification | Group A (first standard), n = 30 |

| Group B (first JetPrep), n = 34 | |

| Age (yr) | 63.53 ± 8.03 |

| Sex | M: 34; F: 30 |

| Risk of developing CRC | High: n = 22; Low: n = 42 |

| BBPS (baseline values) per protocol (n = 64) | 4.84 ± 1.81 |

| BBPS (baseline values) of original patient cohort1 (n = 71) | 5.15 ± 2.04 |

To estimate the mean quality of bowel preparations, the mean score of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale was calculated for all patients. The mean BBPS score was found to be 5.15 ± 2.04 (Table 5; n = 71, 2 patients did not undergo a complete colonoscopy).

| Group A | Group B | P value | |

| (first step: standard cleansing) | (first step: JetPrep) | ||

| Propofol (mg) | 366.33 ± 123.83 | 421.1 ± 151.05 | 0.1161 |

| Investigator | 0.2232 | ||

| Kiesslich R | n = 22 | n = 20 | |

| Murthy S | n = 8 | n = 14 | |

| Withdrawal time (min) | |||

| First step | 7.5 ± 1.92 | 9.41 ± 3.34 | 0.0093 |

| Second step | 8.22 ± 2.25 | 7.60 ± 1.71 | 0.2241 |

| Total | 15.72 ± 4.00 | 17.0 ± 4.70 | 0.2153 |

| Withdrawal time with JetPrep (min) | 8.22 ± 2.25 | 9.41 ± 3.34 | 0.1883 |

| Total duration (min) | 36.23 ± 20.31 | 42.0 ± 18.91 | 0.0733 |

| Intervention time (s) | |||

| First step | 218.77 ± 530.21 | 317.47 ± 638.62 | 0.2893 |

| Second step | 122.47 ± 188.31 | 162.94 ± 361.21 | 0.3763 |

| BBPS basic value | 4.9 ± 1.9 | 4.79 ± 1.79 | 0.8182 |

Thus, on a scale from 0-9 (0 = poorest bowel preparation; 9 = best possible bowel preparation), the mean score was found to be in the middle range. The initial degree of cleansing was similar in both groups. Notably, baseline values for the proximal portions of the bowel were on average lower relative to the rest of the colon and increased progressively as one moved further distally into the colon.

Table 5 provides a direct comparison of additional characteristics that were found during investigation. The withdrawal time needed for the first step of the procedure was significantly longer in group A (9.41 ± 3.34 min), in which the JetPrep system was used, compared to group B (7.5 ± 1.92 min). However, the total withdrawal time did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Large differences were found between the control group and the intervention group with regard to the quantity of water used during cleansing (Table 6). During both steps of the investigation a greater quantity of water was used to cleanse the bowel when the JetPrep system was employed. Because cleansing was stopped after the first examination step when it produced no further positive effect, the difference between groups for the first step was significant (P < 0.001).

This finding was confirmed by the significantly greater quantity of water that was required when using the JetPrep system in the second examination step. However, the overall quantity of water used for both colonoscopies did not differ between groups (Table 6).

Despite differences in water consumption rates none of the 64 study patients experienced complications and all of them could be discharged to go home on the day that they underwent colonoscopy; patients that were already hospitalized were instead sent to the ward for further treatment. A total of 47 (73.4%) out of the 64 patients could be queried about adverse events on the day of the examination; of these, none reported a serious adverse event.

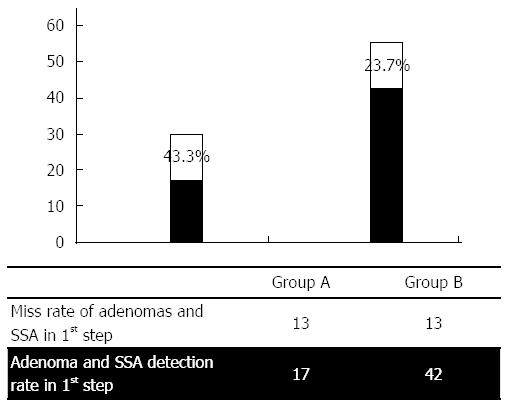

A total of 163 discovered polyps were found amongst the 64 study participants who underwent both investigation steps, of these a total of 103 polyps were found during the first investigation step. In group A, 49.4% of the polyps were detected during the standard bowel cleansing procedure and the miss rate (i.e., polyps discovered during the second step of the procedure) of this group was 50.7%. Group B underwent cleansing with the JetPrep system during the first step of the examination and up to 73.9% of polyps were identified during this step. Thus, the miss rate in group B was only 26.1% (P < 0.001; Table 7).

| Group A | Group B | P value | |

| Polyps, total found | First step: 35 | First step: 68 | < 0.001 |

| Second step: 36 | Second step: 24 | ||

| Miss rates for polyps, total | 50.70% | 26.10% | |

| Polyps on the right side | First step: 13 | First step: 39 | < 0.001 |

| Second step: 20 | Second step: 14 | ||

| Miss rate for polyps | 60.6% | 26.4% | |

| Adenomas, SSA total | First step: 17 | First step: 42 | 0.035 |

| Second step: 13 | Second step: 13 | ||

| Miss rate for adenomas, SSA total | 43.3% | 23.7% | |

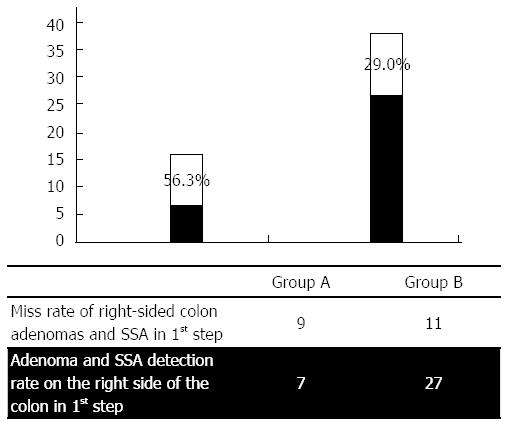

| Adenomas, SSA on the right side | First step: 7 | First step: 27 | 0.043 |

| Second step: 9 | Second step: 11 | ||

| Miss rate for adenomas, SSA on the right side | 56.3% | 29.0% | |

| Adenomas total | First step: 13 | First step: 32 | 0.101 |

| Second step: 11 | Second step: 12 | ||

| Miss rate for adenomas, total | 45.8% | 27.3% | |

| Adenomas on the right side | First step: 3 | First step: 17 | 0.064 |

| Second step: 7 | Second step: 10 | ||

| Miss rate for adenomas on the right side | 70.0% | 37.0% | |

| SSA | First step: 4 | First step: 10 | 0.243 |

| Second step: 2 | Second step: 1 | ||

| Miss rate for SSA | 33.3% | 9.1% |

When considering only the investigations that were performed on the right side of the colon, the miss rate in group A during the first examination was 60.6% compared to 26.4% in group B (P < 0.001).

When including the presence of dysplastic lesions such as LGD, HGD and serrated adenomas in the statistical evaluation, the JetPrep system was proven to be significantly more advantageous with respect to both the entire colon and the proximal portions of the colon (Figure 2).

The graphical presentation of miss rates in the first investigation, shown in Figure 3, reveals higher miss rates for lesions on the right side of the colon vs the remainder of the colon with respect to both overall lesion numbers and adenomas and sessile serrated adenomas (SSAs). The results show that there was a significant increase in the adenoma detection rates that were measured for both group A (n = 7) and group B (n = 27), concurrent with a significant decrease in the miss rates that were calculated for each group (group A: 56.3% vs group B: 29.0%). When comparing the miss rates for polyps that were distributed throughout the colon vs those that were found only on the right side of the colon (Table 7), clear differences were found within the control group (Group A), and virtually no differences were found within the intervention group (Group B). In group A, the miss rate for the detection of all polyps was 50.7%; in group B, this rate was 26.1%. When evaluating only the right side of the colon, the miss rate was found to be 70.0% in group A and 37.0% in group B. Table 7 provides a clear overview of the detection and miss rates between the two groups.

Colonoscopy has become an integral part of disease prevention, and its use is established in many countries. In Germany, it is common that all insured persons that are ≥ 50 years in age undergo a screening colonoscopy for the early detection of colorectal cancer (CRC)[18-21]. Furthermore, a collection of respected editorials advocate colonoscopy as a preferred screening strategy, despite the well-known issues of overlooked adenomas and interval cancers[22].

The results of a cohort study that followed 88902 patients over a period of 22 years found screening colonoscopy to be associated with a reduced incidence of cancer in the distal colorectum; however, only a modest reduction in the incidence of proximal colon cancer was found[23]. As of the time of this writing, screening colonoscopies that are used to identify lesions on the left side of the colon are associated with a significantly reduced risk of mortality (OR = 0.33), however, this association does not hold true with respect to the identification of lesions on the right side of the colon (OR = 0.99).

Previously conducted studies have postulated several reasons to explain why the efficacy of screening colonoscopy is so widely different when used on the left side of the colon vs the right side; it has been unanimously agreed that no single factor can explain this phenomenon with sufficient clarity. The difficulty associated with the preparation of the right side of the colon during bowel cleansing should certainly be considered an important factor when trying to understand why the detection of small flat polyps in this region of the colon is still a challenge[7,23]. In addition to oral laxatives, a variety of intraprocedural cleaning measures can be used to achieve better visibility in the proximal colon. Considering that rinsing the colon with syringes through the working channel of the endoscope is a time-consuming and ineffective process, many other systems are currently being tested to improve visibility during colonoscopy[11-14].

The JetPrep cleansing device is a sterile, disposable system that functions through a shower like spray mechanism while simultaneously permitting stool residues to be suctioned through the working channel of an endoscope. Preliminary studies on the JetPrep system have shown that it achieves significantly better cleansing compared to alternative methods[14].

The prospective crossover study described here demonstrated that significantly better cleansing of the colon was achieved with the JetPrep system than by the standard method using a syringe, especially in poorly prepared portions of the proximal colon (P < 0.001).

In addition to better cleansing, the methodology presented in this study led to higher detection rates for polypoid lesions in the colon and a significant enhancement of lesion detection rates with respect to the right side of the colon (P < 0.001). However, the more relevant feature of this method from the viewpoint of the patient is the enhanced detection of adenomas and dysplastic polyps, as these factors alone constitute a quality criterion that demonstrates the efficacy of the new method and dictates both the intervals of treatment and the prognosis of the patient. Currently, based on the knowledge of the “adenoma-carcinoma sequence”, in some cases the next control investigation is recommended after a rather long period of 10 years[21]. However, recent data have revealed a new serrated pathway that encompasses both SSA and the conventional adenoma-carcinoma pathway[8,24-33].

This type of polyp is usually found on the right side of the colon and because it is shallow, its growth pattern is difficult to detect[34,35]; such polyps tend to be easily overlooked and are therefore responsible for increasing the rate of interval carcinomas associated with screening colonoscopy in addition to having a greater potential of transforming into colorectal cancer[36].

In the present study, we found the JetPrep cleansing device to be significantly superior in facilitating the detection of adenomas and serrated adenomas throughout the colon as compared to standard cleansing with a 50-mL syringe (Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.035) (Figure 4). It is also notable that significantly more adenomas and SSAs were found on the right side of the colon following the use of the JetPrep device (P = 0.043) (Figure 5). A large case-control study that was recently published by Baxter reported a 22% average miss rate for the detection of adenoma (range, 15%-32%) when using tandem colonoscopy and further emphasized the benefit of screening colonoscopy in reducing the rate of mortality caused by interval cancers that arise on the right side of the colon[37].

A similar outcome was achieved in a study performed by Rex; tandem colonoscopy in conjunction with a standard cleansing procedure yielded a miss rate of 25%. Lesions less than 5 mm in size were found to be overlooked more frequently in the first examination step whereas larger lesions were more rarely missed[38].

In contrast to the Rex study, in our present investigation we switched between two cleansing procedures. Significantly more colon adenomas and SSAs were overlooked in patients who underwent the first procedure when a standard cleansing method was employed (43.3% miss rate) (Figure 4). The rate of missed right-sided colonic adenomas and SSAs was even more pronounced (56.3%) (Figure 5).

In patients who underwent cleansing with the JetPrep device during the initial colonoscopy, we registered an overall miss rate of 23.7%, with a 29.0% miss rate for right-sided adenomas. Although our results generally agree with other published studies, detection rates tended to be higher and miss rates correspondingly lower when using the JetPrep flushing device[39]. These results might be explained by the superior cleansing that can be achieved with the JetPrep device. Furthermore, the rate at which we detected adenoma is comparable to that obtained when using white light endoscopy in conjunction with newer add-on devices (e.g., Third Eye Retroscope, cap-assisted colonoscopy). However, one potential bias of our approach that must be noted is the fact that we divided our patient cohort into a high-risk and a low-risk group and that the endoscopist performing the procedure was not blinded as to which group each patient fell within; this knowledge could influence the degree to which the colon was inspected on withdrawal.

The relevance of improved adenoma detection rates (and corresponding reductions in miss rates) from the perspective of the patient is reflected by the high rate of interval carcinomas and by the use of different recommendations for the frequency of screening colonoscopy that is necessary for adenoma detection. In 7 out of 30 patients in group A at least one adenoma or SSA was discovered during the second examination when using the JetPrep system that was not detected during the first standard examination. Thus, in the absence of a second examination, the initial colonoscopy would have been performed too late in 23.3% of patients. With regard to the corresponding values for group B, fewer patients (8.8%) would have been subjected to an incorrect screening interval after the first examination step with JetPrep (3 of 34 patients). With regard to withdrawal times, a significantly longer withdrawal time was necessary when using the JetPrep system during the first examination (9.41 ± 3.34 min vs 7.5 ± 1.92 min, P < 0.009); the withdrawal period for the second examination was nearly just as long (8.22 ± 2.25 min vs 7.6 ± 1.71 min, P = 0.224). To rule out systematic errors, we calculated the difference in total investigation times for both groups as well as any differences caused by the JetPrep steps and no significant difference was found for either of these parameters between the two groups.

Based on the collective findings detailed above, we can conclude that patients with relevant residual staining are subject to a much higher risk of missed dysplastic lesions. However, it should be noted that the colonoscopies performed in our study were conducted by only two highly experienced endoscopists and that every back-to-back examination was performed by the same investigator, who was not blinded to the results of the first screen.

Furthermore, even advanced cleansing procedures are limited in their ability to enhance the detection of polyps that are concealed behind folds.

In addition to new options becoming available for bowel cleansing, there has also been an increase in the development of new endoscopic techniques, all of which are aimed at enhancing imaging techniques to improve the detection of adenomas and/or combating interval carcinoma.

These new techniques utilize items such as a retro-viewing device (Third Eye Retroscope, Avantis Medical, Sunnyvale, CA), a colonoscope equipped with an integrated balloon at its distal tip (NaviAidTM G-EYE, Smart Medical Systems, Israel), or a full spectrum endoscope (FUSE, EndoChoice, Alpharetta, GA, United States) that can provide the endoscopist with a 330-degree field of vision. Each of these techniques enables the inspection of the proximal surfaces of haustral folds, which are not in the line of vision of the endoscope’s forward-viewing optics. Thus far the results obtained from using such devices have been associated with enhanced adenoma detection rates compared with standard colonoscopy[40-43].

Nevertheless, the techniques discussed above should not be considered as direct competitors that will rule out the use of the JetPrep system; rather, they emphasize the fact that the problem of overlooked adenomas is a persistent one. In fact, the JetPrep system may be used to complement the new technical procedures because of its universal ability to be applied through the working channel of the endoscope. In fact it would even be desirable to explore the combination of JetPrep and these new technologies; such investigations would likely yield even more favorable results than those achieved so far.

In summary, the JetPrep flushing device is safe to use and is the first intraprocedural cleansing system that significantly increases detection rates of right-sided neoplastic lesions (adenomas/SSA). Although based on a relatively small single-center, prospective, randomized clinical study, the JetPrep flushing device may be recommended for use in screening colonoscopies to improve the preparation of the bowel and therefore increase the rate of polyp detection.

Although screening colonoscopy is considered the gold standard for identifying lesions within the bowel, the problem of overlooked adenomas and interval cancers is increasing.

The literature postulates several reasons to explain why the efficacy of screening colonoscopy differs widely between the left and right sides of the colon; it is unanimously agreed that no single factor can explain this phenomenon with sufficient clarity.

Flat and sessile polyps are shallow and difficult to detect. These polyps tend to be easily overlooked and possess a greater potential for transformation into colorectal cancer. They may therefore be responsible for interval carcinomas after screening. In the present study the authors found that the JetPrep cleansing system is superior to standard cleansing with respect to facilitating the detection of both adenomas and serrated adenomas throughout the colon.

Any improvement that can be made to the detection rate of adenoma is highly relevant for patients with regard to recommended control intervals for colonoscopies performed to detect adenomas.

The JetPrep system is a new irrigation system for intraprocedural colon cleansing. The system functions in a similar way to a showerhead and is introduced through the working channel of the endoscope.

The authors have investigated an important issue concerning bowel preparation in what appears to be the first randomized, prospective, crossover study designed to examine intraprocedural bowel cleansing with the newly developed JetPrep system during colonoscopy. Quality outcomes such as bowel preparation and adenoma detection rates were examined.

P- Reviewer: Beltran VP, Greenspan M, Jiang YH S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Baxter NN, Warren JL, Barrett MJ, Stukel TA, Doria-Rose VP. Association between colonoscopy and colorectal cancer mortality in a US cohort according to site of cancer and colonoscopist specialty. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2664-2669. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 253] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bressler B, Paszat LF, Vinden C, Li C, He J, Rabeneck L. Colonoscopic miss rates for right-sided colon cancer: a population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:452-456. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Singh H, Nugent Z, Demers AA, Kliewer EV, Mahmud SM, Bernstein CN. The reduction in colorectal cancer mortality after colonoscopy varies by site of the cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1128-1137. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 363] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bowles CJ, Leicester R, Romaya C, Swarbrick E, Williams CB, Epstein O. A prospective study of colonoscopy practice in the UK today: are we adequately prepared for national colorectal cancer screening tomorrow? Gut. 2004;53:277-283. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: oral bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:373-384. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Aslinia F, Uradomo L, Steele A, Greenwald BD, Raufman JP. Quality assessment of colonoscopic cecal intubation: an analysis of 6 years of continuous practice at a university hospital. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:721-731. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378-384. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:76-79. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Westwood DA, Alexakis N, Connor SJ. Transparent cap-assisted colonoscopy versus standard adult colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:218-225. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tee HP, Corte C, Al-Ghamdi H, Prakoso E, Darke J, Chettiar R, Rahman W, Davison S, Griffin SP, Selby WS. Prospective randomized controlled trial evaluating cap-assisted colonoscopy vs standard colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3905-3910. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Eliakim R, Yassin K, Lachter J, Chowers Y. A novel device to improve colon cleanliness during colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2012;44:655-659. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rigaux J, Juriens I, Devière J. A novel system for the improvement of colonic cleansing during colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2012;44:703-706. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fritscher-Ravens A, Mosse CA, Mills T, Ikeda K, Swain P. Colon cleaning during colonoscopy: a new mechanical cleaning device tested in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:141-143. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Kiesslich R, Schuster N, Hoffman A, Goetz M, Galle PR, Santo E, Halpern Z. MedJet--a new CO2-based disposable cleaning device allows safe and effective bowel cleansing during colonoscopy: a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:767-771. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, Levin TR, Burt RW, Johnson DA, Kirk LM, Litlin S, Lieberman DA, Waye JD. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1296-1308. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Greenlaw RL. Effect of a time-dependent colonoscopic withdrawal protocol on adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1091-1098. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 205] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 671] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 788] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374-1403. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3526] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3571] [Article Influence: 324.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Jemal A, Tiwari RC, Murray T, Ghafoor A, Samuels A, Ward E, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ; American Cancer Society. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:8-29. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Johnson D. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570-1595. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1423] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1419] [Article Influence: 88.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Boyle P, Ferlay J. Cancer incidence and mortality in Europe, 2004. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:481-488. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zwierko M, Rupinski M, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1795-1803. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1287] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1351] [Article Influence: 96.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Liao X, Qian ZR, Inamura K, Kim SA, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1095-1105. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 968] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1047] [Article Influence: 95.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hurlstone DP, Cross SS, Adam I, Shorthouse AJ, Brown S, Sanders DS, Lobo AJ. A prospective clinicopathological and endoscopic evaluation of flat and depressed colorectal lesions in the United Kingdom. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2543-2549. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Teixeira CR, Tanaka S, Haruma K, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G, Shimamoto F. Flat-elevated colorectal neoplasms exhibit a high malignant potential. Oncology. 1996;53:89-93. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Tsuda S, Veress B, Tóth E, Fork FT. Flat and depressed colorectal tumours in a southern Swedish population: a prospective chromoendoscopic and histopathological study. Gut. 2002;51:550-555. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Baretton GB, Autschbach F, Baldus S, Bläker H, Faller G, Koch HK, Langner C, Lüttges J, Neid M, Schirmacher P. [Histopathological diagnosis and differential diagnosis of colorectal serrated polys: findings of a consensus conference of the working group “gastroenterological pathology of the German Society of Pathology”]. Pathologe. 2011;32:76-82. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bosman FT, Carbeuri F, Hruban RH, Theisen ND. WHO classification of tumors of the digestive system. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO Press 2010; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Torlakovic E, Skovlund E, Snover DC, Torlakovic G, Nesland JM. Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:65-81. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Lazarus R, Junttila OE, Karttunen TJ, Mäkinen MJ. The risk of metachronous neoplasia in patients with serrated adenoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:349-359. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Jass JR. Serrated route to colorectal cancer: back street or super highway? J Pathol. 2001;193:283-285. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Higaki S, Hashimoto S, Harada K, Nohara H, Saito Y, Gondo T, Okita K. Long-term follow-up of large flat colorectal tumors resected endoscopically. Endoscopy. 2003;35:845-849. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Goldstein NS. Clinical significance of (sessile) serrated adenomas: Another piece of the puzzle. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:329-330. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Oono Y, Fu K, Nakamura H, Iriguchi Y, Yamamura A, Tomino Y, Oda J, Mizutani M, Takayanagi S, Kishi D. Progression of a sessile serrated adenoma to an early invasive cancer within 8 months. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:906-909. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kee F, Wilson RH, Gilliland R, Sloan JM, Rowlands BJ, Moorehead RJ. Changing site distribution of colorectal cancer. BMJ. 1992;305:158. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Gupta S, Balasubramanian BA, Fu T, Genta RM, Rockey DC, Lash R. Polyps with advanced neoplasia are smaller in the right than in the left colon: implications for colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1395-1401.e2. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L. Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:1-8. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Rex DK, Cutler CS, Lemmel GT, Rahmani EY, Clark DW, Helper DJ, Lehman GA, Mark DG. Colonoscopic miss rates of adenomas determined by back-to-back colonoscopies. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:24-28. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Harrison M, Singh N, Rex DK. Impact of proximal colon retroflexion on adenoma miss rates. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:519-522. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | Triadafilopoulos G, Li J. A pilot study to assess the safety and efficacy of the Third Eye retrograde auxiliary imaging system during colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2008;40:478-482. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | DeMarco DC, Odstrcil E, Lara LF, Bass D, Herdman C, Kinney T, Gupta K, Wolf L, Dewar T, Deas TM. Impact of experience with a retrograde-viewing device on adenoma detection rates and withdrawal times during colonoscopy: the Third Eye Retroscope study group. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:542-550. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Halpern Z, Gross SA, Gralnek IM, Shpak B, Pochapin M, Hoffman A, Mizrahi M, Rochberger YS, Moshkowitz M, Santo E. Comparison of adenoma detection and miss rates between a novel balloon colonoscope and standard colonoscopy: a randomized tandem study. Endoscopy. 2015;47:238-244. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gralnek IM, Segol O, Suissa A, Siersema PD, Carr-Locke DL, Halpern Z, Santo E, Domanov S. A prospective cohort study evaluating a novel colonoscopy platform featuring full-spectrum endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2013;45:697-702. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |