Published online Jan 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.581

Revised: July 31, 2012

Accepted: August 8, 2012

Published online: January 28, 2013

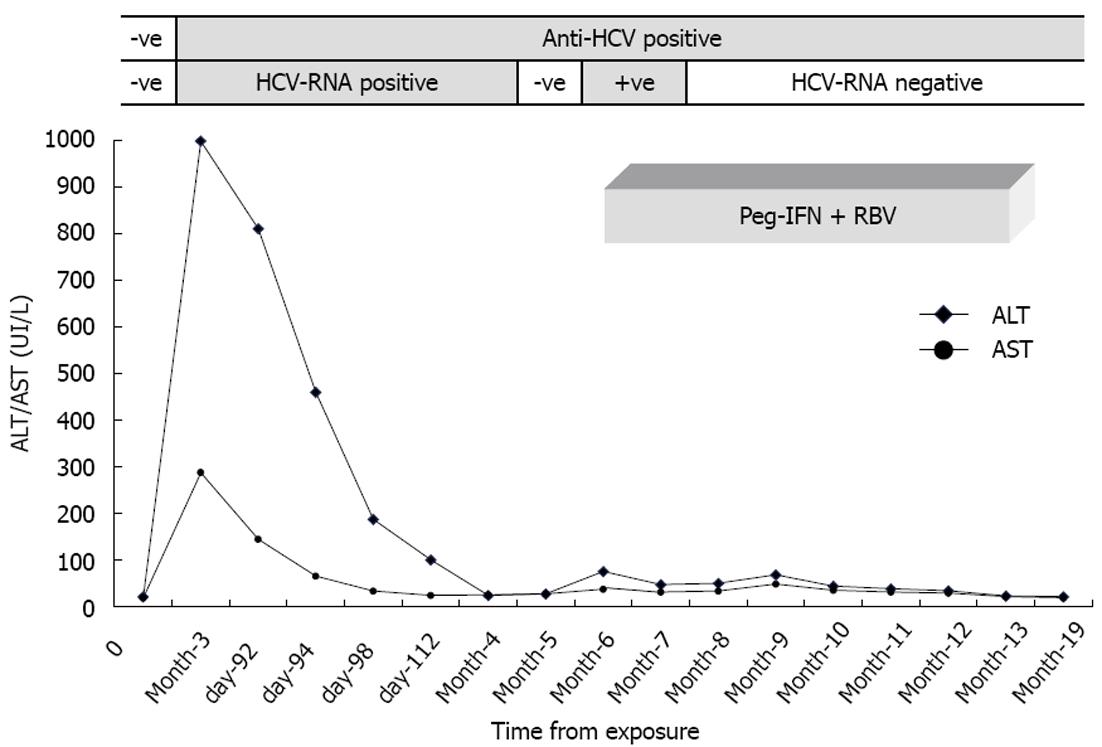

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection after biological accident (needlestick injury) is a rare event. This report describes the first case of acute HCV infection after a needlestick injury in a female nursing student at Padua University Hospital. The student nurse was injured on the second finger of the right hand when recapping a 23-gauge needle after taking a blood sample. The patient who was the source was a 72-year-old female with weakly positive anti-HCV test results. Three months after the injury, at the second step of follow-up, a relevant increase in transaminases with a low viral replication activity (350 IU/mL) was observed in the student, indicating HCV infection. The patient tested positive for the same genotype (1b) of HCV as the injured student. A rapid decline in transaminases, which was not accompanied by viral clearance, and persistently positive HCV-RNA was described 1 mo later. Six months after testing positive for HCV, the student was treated with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin for 24 wk. A rapid virological response was observed after 4 wk of treatment, and a sustained virological response (SVR) was evident 6 mo after therapy withdrawal, confirming that the patient was definitively cured. Despite the favourable IL28B gene (rs12979860) CC- polymorphism observed in the patient, which is usually predictive of a spontaneous clearance and SVR, spontaneous viral clearance did not take place; however, infection with this genotype was promising for a sustained virological response after therapy.

- Citation: Scaggiante R, Chemello L, Rinaldi R, Bartolucci GB, Trevisan A. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in a nurse trainee following a needlestick injury. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(4): 581-585

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i4/581.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.581

The incidence rate of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has been dramatically reduced since the advent of blood products screening and the introduction of single-use medical equipment. However, acute hepatitis C is still present in Western countries. In Italy, the incidence ranges from 1 to 14 cases per 100 000 according to the National Surveillance Agency[1], the Italian Blood Program[2] and by evaluation in the general population[3].

Currently, intravenous (IV) drug use is the most common exposure leading to HCV infection, with HCV prevalence rates of 50%-80% in long-term IV drug abusers. Other possible modes of acquisition are medical procedures, sexual intercourse and needlestick injuries, particularly in health care professionals[4-7]. The average rate of HCV transmission after a single needlestick exposure depends on the amount of inoculated blood, increasing to 0.9% with a hollow needle full of blood and decreasing to 0.3% for conjunctival exposure[8]. In our previous experience at the Padua University Teaching Hospital no cases resulted in seroconversion[9].

In the present report, the first case of HCV seroconversion in our hospital following a needlestick injury is reported. Even though the spontaneous rate of viral clearance after acute hepatitis C ranges from 20% to 50%[5,10] and it can be predicted by measurement of serum viral load[11], which should become negative within 12-14 wk after the exposure, the injured patient developed acute hepatitis without spontaneous viral clearance. The student nurse was treated with pegylated interferon and ribavirin.

A 19-year-old female student nurse was injured on the second finger of the right hand when recapping a 23-gauge needle after taking a blood sample. The patient who was the source was a 72-year-old female, weakly positive for anti-HCV by chemiluminescence (CIA) (VITROS, anti-HCV assay, Ortho Clinical Diagnostic, Abbott Laboratories, IL, United States) with an undetermined pattern (only C1+ and C2+) at confirmatory test by immunoblot assay (HCV-RIBA 3.0 assay, Chiron Corporation, United States). Moreover, the patient had a quantitative HCV-RNA level of 14 491 571 IU/mL (COBAS TaqMan, Roche, Basel) and viral genotyping showed HCV-1b (VERSANT® HCV genotype 2.0, INNOLiPA, Innogenetics, Belgium).

The student nurse was checked and followed according to the SIROH recommendations and procedures, which consist of the assessment of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis C antibody and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody at the time of injury (step 1), 3 mo after the injury (step 2), and 6 mo after the injury (step 3). At the time of the injury she was anti-HBsAg positive (recently vaccinated) and HIV and HCV negative. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were within the reference range.

At the second step (3 mo after injury), a high increase in transaminases with a HCV seroconversion (CIA: anti-HCV positive and RIBA: NS4+, NS3+, C1+++, C2+++, GST-) was detected in the student nurse. The student had a quantitative HCV-RNA level of 330 IU/mL and the HCV genotype was also 1b, as was that of the patient source. Despite the fact that the injured student nurse had no symptoms, she was diagnosed with acute HCV infection. Transaminases were frequently analysed, decreasing until normalization at 4 mo after the injury (Figure 1). HCV-RNA was detectable, but below the lower limit of the linearity range (< 43 IU/mL) and was negative 5 mo after injury. At this time, AST and ALT persisted within the reference range. Unfortunately, 6 mo after injury a recurrence of viraemia (HCV-RNA positive, < 43 IU/mL) together with a slight ALT spike were observed. One month later, further analysis confirmed low viral load and an increase in transaminases.

Due to the chronic profile of the infection, antiviral therapy was prescribed and the subject received a regimen consisting of 180 µg pegylated interferon α-2a subcutaneously once a week and 400 mg ribavirin (adjusted for weight), by mouth twice a day.

During this treatment (Figure 1), a persistent transaminasemia and a slight neutrophilic leukopenia were evident. HCV-RNA analysis showed that the patient remained persistently negative beginning at week 4 of therapy. The patient suffered profound fatigue and musculoskeletal pain, which showed a good response to acetaminophen. During the last month of therapy, she had severe knee pain that was resistant to acetaminophen and only partially mitigated by other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). Therapy lasted 24 wk without any adjustment to the drug dose.

At one month after therapy withdrawal the patient had increasing asthenia and unexplained anaemia (Hb 82 g/L, reference values 123-153 g/L) that resolved with vitamins and iron supplementation, and was probably due to NSAID-induced gastrointestinal bleeding. At 6 mo, HCV-RNA analysis remained negative, transaminases remained within the reference values, the patient felt well and her blood cell counts were restored.

Annual monitoring of HCV-RNA and liver function tests confirmed viral eradication and resolution of the liver disease up to 36 mo from the onset of the infection, thus the patient was defined as “cured”.

Needle recapping is an unsuitable operation, which is usually performed only by expert physicians[12]. Student nurses should only use standard precautions and procedures and the subject of this case report has been re-educated according to the protocol following her professional exposure.

Because the student had no history of blood transfusion, sexual behaviour or IV drug abuse between the time of injury and the onset of acute HCV, it was highly probable that the lesion with the contaminated source was the cause of seroconversion. Furthermore, the student nurse had the same HCV-1b genotype as the patient; however, sequence analysis comparing the source and student nurse HCV-RNA would be required to eliminate all doubt.

The average rate of HCV transmission after a single needlestick exposure is low[13], and the transmission rate in Italy is as low as 0.4%[8]. The higher seroprevalence in health care workers[2] is probably related to the fact that health care workers are submitted to follow-up after biological contamination, therefore, there is a greater rate of discovery of seroconversions than in other workers not submitted to surveillance for biological risk. The adherence to procedures after biological exposure is important, because patients with acute HCV infection are often asymptomatic and this makes diagnosis difficult and cases remain underestimated[14].

The expectation of a spontaneous viral clearance was initially high in our subject due to the normalization of transaminases and the transient HCV-RNA negativity. Some factors have been proposed as being associated with spontaneous viral clearance including ethnicity[15,16], short incubation period[17], rapid decline in HCV-RNA level[11], and female gender[18]. Unfortunately, despite the age, gender, absence of additional risk factors, rapid normalization of transaminases[19], low viral load (330 IU/mL, approximately 7000 copies/mL) and favourable IL28B gene (rs12979860) CC-polymorphism[20] no spontaneous viral clearance was observed in our subject. This was probably due to persistence of the virus (> 3 mo from onset), and particularly to the host complex immunological mechanisms that are associated with spontaneous clearance or to chronic infection (Table 1)[21-30].

| Immunologic marker | Mechanism involved | Ref. | |

| Acute phase of HCV infection and predictive of viral clearance | IFN-α/-β | Vigorous IFN-stimulated genes; inhibition of IL12 expression | [21] |

| IFN-γ | HCV core induced generation of reactive oxygen species with stimulation of monocytes and NKs | [22] | |

| IFN-λ | Host IL28B gene polymorphism (CC allele favorable) | [23] | |

| CD4/CD8 | Multispecific intrahepatic Th1 T cells activation | [26] | |

| HLA-B27/-B57/-A3 | Protective HLA alleles on T cell epitopes | [29] | |

| HCV persistence and chronicity of infection | TGF-β/IL10 | Inhibition of anti-HCV core/NS2 Th1 response | [24,25] |

| CD161 | HCV-specific Th17 T cells regulated by TGF-β and IL10 | [27] | |

| HCV HVR-1 specific Abs | Viral escape from Abs mediated neutralization | [28] | |

| PD1/2B4/CD160 | Inhibitory T cell receptors on CD8+ cells | [30] |

In general, following injury with a HCV source, no post-exposure prophylaxis is indicated; on the other hand, whether and how to treat acute HCV infection is still up for debate. The use of α-interferon may be effective in preventing progression from acute to chronic disease[31], but there are no data to indicate that early treatment during the course of chronic infection is less effective than immediate treatment during the acute phase. Certainly, we must consider that in 20%-30% of cases, after an acute infection, spontaneous clearance of HCV occurs and that antiviral therapy is expensive and not well tolerated in the majority of cases[32]. Delaying treatment for 12-16 wk after disease onset permits the identification of cases whose infections spontaneously resolve and whether early initiation of treatment is more appropriate in cases with genotype 1b and/or with asymptomatic disease is still an open question.

The aim of therapy is to achieve a sustained virological response (SVR), defined as the absence of HCV-RNA in serum 6 mo after therapy withdrawal[33]. In acute infection, which has the favourable features of low pretreatment HCV-RNA levels and HCV-genotype non-1 correlate, SVR varies between 71% and 94%[34-37] and is certainly higher than the rate obtained in cases with long time chronic infection[38].

During therapy, the student nurse showed a rapid virological response (RVR), defined as the absence of HCV-RNA at 4 wk after therapy withdrawal[39], which was maintained at 6 mo after therapy withdrawal, thus, she was defined as having a SVR. These findings confirm that the earlier the virus disappears from serum the higher the probability of achieving a sustained response to treatment.

This case report supports the vigorous application of measures to increase adherence to protocols after biological contamination. We believe that all cases, if there are no contraindications, should be evaluated promptly to prescribe a standard full antiviral schedule of pegylated interferon and weight-based ribavirin, especially in cases like this one in which there is a viral kinetic showing a transient or slow resolution of the active infection. Currently, response-guided therapy helps to determine the duration of treatment, which is cost saving and more advantageous for patients[40]. In this case report, the RVR allowed for the use of a shorter schedule, 24 wk of therapy, which is approximately 12.000 € less than the standard of 48 wk.

In conclusion, the lessons from this case are as follows: (1) health care workers must be counselled and trained to avoid occupational exposure; (2) all injured cases must report the exposure immediately and undergo standard procedures; and (3) a weight-adjusted full schedule of the standard regimen with pegylated interferon and ribavirin should be proposed in all cases with acute HCV infection showing an active and longer viral replication, in particular for cases with more than 6 mo of acquisition. These suggestions might help to avoid the unaware HCV-carrier status, and thus some chronic infections with the potential progression to cirrhosis and to major complications, such as hepatocellular carcinoma.

P- Reviewers Schvoerer E, Wang JT S- Editor Lv S L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Mele A, Tosti ME, Marzolini A, Moiraghi A, Ragni P, Gallo G, Balocchini E, Santonastasi F, Stroffolini T. Prevention of hepatitis C in Italy: lessons from surveillance of type-specific acute viral hepatitis. SEIEVA collaborating Group. J Viral Hepat. 2000;7:30-35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tosti ME, Mariano A, Spada E, Pizzuti R, Gallo G, Ragni P, Zotti C, Lopalco P, Curtale F, Graziani G. Incidence of parenterally transmitted acute viral hepatitis among healthcare workers in Italy. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:629-632. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kondili LA, Chionne P, Costantino A, Villano U, Lo Noce C, Pannozzo F, Mele A, Giampaoli S, Rapicetta M. Infection rate and spontaneous seroreversion of anti-hepatitis C virus during the natural course of hepatitis C virus infection in the general population. Gut. 2002;50:693-696. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Prati D. Transmission of hepatitis C virus by blood transfusions and other medical procedures: a global review. J Hepatol. 2006;45:607-616. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 177] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Santantonio T, Medda E, Ferrari C, Fabris P, Cariti G, Massari M, Babudieri S, Toti M, Francavilla R, Ancarani F. Risk factors and outcome along a larger patient cohort with community-acquired acute hepatitis C in Italy. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1154-1159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Deterding K, Wiegand J, Grüner N, Wedemeyer H. Medical procedures as a risk factor for HCV infection in developed countries: do we neglect a significant problem in medical care? J Hepatol. 2008;48:1019-1020; author reply 1020-1021. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Martínez-Bauer E, Forns X, Armelles M, Planas R, Solà R, Vergara M, Fàbregas S, Vega R, Salmerón J, Diago M. Hospital admission is a relevant source of hepatitis C virus acquisition in Spain. J Hepatol. 2008;48:20-27. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ippolito G, Puro V, Petrosillo N, De Carli G. Surveillance of occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens in health care workers: the Italian national programme. Euro Surveill. 1999;4:33-36. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Davanzo E, Frasson C, Morandin M, Trevisan A. Occupational blood and body fluid exposure of university health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:753-756. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Micallef JM, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ. Spontaneous viral clearance following acute hepatitis C infection: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:34-41. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 589] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 598] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hofer H, Watkins-Riedel T, Janata O, Penner E, Holzmann H, Steindl-Munda P, Gangl A, Ferenci P. Spontaneous viral clearance in patients with acute hepatitis C can be predicted by repeated measurements of serum viral load. Hepatology. 2003;37:60-64. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 145] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Doebbeling BN, Vaughn TE, McCoy KD, Beekmann SE, Woolson RF, Ferguson KJ, Torner JC. Percutaneous injury, blood exposure, and adherence to standard precautions: are hospital-based health care providers still at risk? Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1006-1013. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jagger J, Puro V, De Carli G. Occupational transmission of hepatitis C virus. JAMA. 2002;288:1469; author reply 1469-1471. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 235] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Blackard JT, Shata MT, Shire NJ, Sherman KE. Acute hepatitis C virus infection: a chronic problem. Hepatology. 2008;47:321-331. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Thomas DL, Astemborski J, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA, Ray SC, Nelson KE, Galai N, Nolt KR, Laeyendecker O, Todd JA. Determinants of the quantity of hepatitis C virus RNA. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:844-851. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang CC, Krantz E, Klarquist J, Krows M, McBride L, Scott EP, Shaw-Stiffel T, Weston SJ, Thiede H, Wald A. Acute hepatitis C in a contemporary US cohort: modes of acquisition and factors influencing viral clearance. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1474-1482. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 148] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hwang SJ, Lee SD, Lu RH, Chu CW, Wu JC, Lai ST, Chang FY. Hepatitis C viral genotype influences the clinical outcome of patients with acute posttransfusion hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 2001;65:505-509. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Page K, Hahn JA, Evans J, Shiboski S, Lum P, Delwart E, Tobler L, Andrews W, Avanesyan L, Cooper S. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in young adult injection drug users: a prospective study of incident infection, resolution, and reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1216-1226. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 234] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yeung LT, To T, King SM, Roberts EA. Spontaneous clearance of childhood hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:797-805. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, Heinzen EL, Qiu P, Bertelsen AH, Muir AJ. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399-401. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2776] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2666] [Article Influence: 177.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Klenerman P, Thimme R. T cell responses in hepatitis C: the good, the bad and the unconventional. Gut. 2012;61:1226-1234. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 116] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Thimme R, Bukh J, Spangenberg HC, Wieland S, Pemberton J, Steiger C, Govindarajan S, Purcell RH, Chisari FV. Viral and immunological determinants of hepatitis C virus clearance, persistence, and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15661-15668. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 469] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tillmann HL, Thompson AJ, Patel K, Wiese M, Tenckhoff H, Nischalke HD, Lokhnygina Y, Kullig U, Göbel U, Capka E. A polymorphism near IL28B is associated with spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus and jaundice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1586-192, 1592.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 235] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Brady MT, MacDonald AJ, Rowan AG, Mills KH. Hepatitis C virus non-structural protein 4 suppresses Th1 responses by stimulating IL-10 production from monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:3448-3457. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Alatrakchi N, Graham CS, van der Vliet HJ, Sherman KE, Exley MA, Koziel MJ. Hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD8+ cells produce transforming growth factor beta that can suppress HCV-specific T-cell responses. J Virol. 2007;81:5882-5892. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 83] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Thimme R, Oldach D, Chang KM, Steiger C, Ray SC, Chisari FV. Determinants of viral clearance and persistence during acute hepatitis C virus infection. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1395-1406. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 899] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 884] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rowan AG, Fletcher JM, Ryan EJ, Moran B, Hegarty JE, O’Farrelly C, Mills KH. Hepatitis C virus-specific Th17 cells are suppressed by virus-induced TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2008;181:4485-4494. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Pestka JM, Zeisel MB, Bläser E, Schürmann P, Bartosch B, Cosset FL, Patel AH, Meisel H, Baumert J, Viazov S. Rapid induction of virus-neutralizing antibodies and viral clearance in a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6025-6030. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 417] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fitzmaurice K, Petrovic D, Ramamurthy N, Simmons R, Merani S, Gaudieri S, Sims S, Dempsey E, Freitas E, Lea S. Molecular footprints reveal the impact of the protective HLA-A*03 allele in hepatitis C virus infection. Gut. 2011;60:1563-1571. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nakamoto N, Kaplan DE, Coleclough J, Li Y, Valiga ME, Kaminski M, Shaked A, Olthoff K, Gostick E, Price DA. Functional restoration of HCV-specific CD8 T cells by PD-1 blockade is defined by PD-1 expression and compartmentalization. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1927-1937. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 233] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Noguchi S, Sata M, Suzuki H, Ohba K, Mizokami M, Tanikawa K. Early therapy with interferon for acute hepatitis C acquired through a needlestick. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:992-994. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Manns MP, Wedemeyer H, Cornberg M. Treating viral hepatitis C: efficacy, side effects, and complications. Gut. 2006;55:1350-1359. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 479] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2011;55:245-264. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 889] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 968] [Article Influence: 74.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | De Rosa FG, Bargiacchi O, Audagnotto S, Garazzino S, Cariti G, Raiteri R, Di Perri G. Dose-dependent and genotype-independent sustained virological response of a 12 week pegylated interferon alpha-2b treatment for acute hepatitis C. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:360-363. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kamal SM, Moustafa KN, Chen J, Fehr J, Abdel Moneim A, Khalifa KE, El Gohary LA, Ramy AH, Madwar MA, Rasenack J. Duration of peginterferon therapy in acute hepatitis C: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2006;43:923-931. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 107] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wiegand J, Buggisch P, Boecher W, Zeuzem S, Gelbmann CM, Berg T, Kauffmann W, Kallinowski B, Cornberg M, Jaeckel E. Early monotherapy with pegylated interferon alpha-2b for acute hepatitis C infection: the HEP-NET acute-HCV-II study. Hepatology. 2006;43:250-256. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 182] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Calleri G, Cariti G, Gaiottino F, De Rosa FG, Bargiacchi O, Audagnotto S, Quaglia S, De Blasi T, Romano P, Traverso A. A short course of pegylated interferon-alpha in acute HCV hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:116-121. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | McHutchison JG, Lawitz EJ, Shiffman ML, Muir AJ, Galler GW, McCone J, Nyberg LM, Lee WM, Ghalib RH, Schiff ER. Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:580-593. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 894] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 872] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yasin T, Riley TR, Schreibman IR. Current treatment of choice for chronic hepatitis C infection. Infect Drug Resist. 2011;4:11-18. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Di Martino V, Richou C, Cervoni JP, Sanchez-Tapias JM, Jensen DM, Mangia A, Buti M, Sheppard F, Ferenci P, Thévenot T. Response-guided peg-interferon plus ribavirin treatment duration in chronic hepatitis C: meta-analyses of randomized, controlled trials and implications for the future. Hepatology. 2011;54:789-800. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |