Published online Oct 21, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i39.6188

Revised: March 18, 2005

Accepted: March 21, 2005

Published online: October 21, 2005

AIM: Before pegylated interferon alpha (IFN) was introduced for the therapy of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV)-induced hepatitis, conventional thrice weekly IFN therapy was supplemented by ribavirin. Also, at that time, higher and more frequent doses of IFN were expected to be more effective than the standard regimen of 3 MU thrice weekly. As ribavirin significantly increases side effects and negatively influences the quality of life particularly in young patients, we started a prospective non-randomized study with a daily IFN-2a monotherapy as an initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C.

METHODS: Forty-six consecutive chronic HCV-infected patients received 3 MU IFN-2a per day as an initial treatment. Patients with genotype 2 or 3 (n = 12) were treated for 24 wk, and patients with genotypes other than 2 or 3 (n = 34) for 48 wk. Treatment outcome was followed up for 48 wk after the end of treatment (EOT). Virological response was defined as the absence of detectable serum HCV-RNA. Patients without virological response at 12 wk after the start of treatment received low-dose ribavirin (10 mg(kg·d)) additionally.

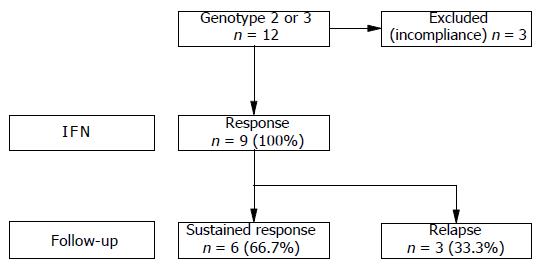

RESULTS: During treatment, three genotype 3 patients were excluded from the study due to incompliance. The remaining patients (n = 9) infected with genotype 2 or 3 showed an initial virological response rate of 100%. Six patients (66.7%) were still found to be virus-free at the end of follow-up period. In these patients, initial virological response was evident already after 2 wk of treatment. In contrast, initial virological response occurred first after 4 wk of treatment in the three patients who relapsed (33.3%). In comparison, patients infected with genotypes other than 2 or 3 (n = 34) showed an initial virological response rate of only 23.5% (n = 8), and even in combination with ribavirin a sustained virological response (SVR) rate of only 11.8% (n = 4) could be achieved.

CONCLUSION: In chronic HCV-infected patients with genotype 2 or 3, a SVR can be expected after 24 wk of daily dose IFN-2a treatment without ribavirin, if initial virological response develops early. This finding is worth to be confirmed in a prospective randomized study with pegylated IFN.

- Citation: Wietzke-Braun P, Meier V, Neubauer-Saile K, Mihm S, Ramadori G. Treatment of genotype 2 and 3 chronic hepatitis C virus-infected patients. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(39): 6188-6192

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i39/6188.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i39.6188

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common infectious agent associated with post-transfusion and community-acquired non-A-non-B hepatitis as well as cryptogenic cirrhosis[1,2]. Most of the patients with acute HCV infection will develop chronic liver disease[2]. In studies with 10-20 years of follow-up, cirrhosis secondary to chronic HCV infection develops in 20-30%[2,3]and is the most common indication for liver transplantation worldwide[4]. Also, patients with HCV-associated cirrhosis have an increased risk for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, which is estimated to be between 1% and 4% per year [5].

Even before the discovery of HCV, introduction of interferon alpha (IFN) for the treatment of non-A-non-B hepatitis was an outstanding revolution in antiviral therapy in 1986[6]. Initial therapeutic regimen consisted of 3 MU IFN thrice weekly (TIW) for 6 mo. The response rate at the end of treatment (EOT) resulted in 29-32%[7,8], but the sustained virological response (SVR) rate was only about 6-18%[7-10]. Apart from extending the duration of IFN monotherapy to 12 or 18 mo, higher doses of IFN TIW failed to significantly increase virologic response rates at EOT and SVR rates (range 13-20%) in most studies[7,11,12]. Combination of IFN 3 MU TIW and ribavirin 1 000-1 200 mg/d for 6 mo was shown to increase the response rate at EOT up to 53-57% and SVR rates up to 31-35%[7,12]. With the combination of IFN 3 MU TIW and ribavirin 1 000-1 200 mg/d for 12 mo, the response rates at EOT of 50-54% and SVR rates of 38-47% could be obtained[7,12-14]. However, ribavirin can increase side effects (e.g., hemolysis and renal dysfunction) and has been shown to have teratogenic and/or embryocidal effects[15]. Many HCV-infected patients are either women at child bearing age or fertile men. Thus, addition of ribavirin to IFN should be avoided when possible. One of the reasons for marginal response to IFN is its short half-life of approximately 8 h[16] which leads to wide fluctuations in IFN plasma concentrations during treatment. Among patients treated with IFN TIW, an intermittent increase in viral load can be observed on treatment-free days[17]. Daily dose IFN therapy might sustain more stable IFN plasma concentrations, thus maintaining a better antiviral effect on HCV. Viral kinetic studies suggest that higher and more frequent doses of IFN may improve the initial response rate and may be more effective in HCV clearance[18,19]. Therefore, we evaluated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of initial daily IFN monotherapy in naive patients with chronic HCV-infection. This monocentric non-randomized study was started before pegylated IFN was introduced into the market.

Patients who were 18 years or older, with compensated chronic HCV infection, not previously treated with IFN or ribavirin were eligible for the study. Eligible patients had persistent elevations of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and/or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activities for at least 6 mo before the start of treatment, a positive third-generation anti-HCV test using an immunoblot procedure (CHIRON RIBA HCV 3.0 SIA, Ortho Diagnostic Systems Inc., Raritan, USA), and positive serum HCV RNA by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Patients with decompensated liver disease, serum elevated alpha-fetoprotein concentration, previous organ transplantation, severe cardiac or chronic pulmonary disease, neoplastic disease, seizure disease, hemoglobinopathies, poorly controlled diabetes, severe retinopathy, autoimmune disorders, thyroid gland alterations, active alcohol or injection drug abuse, history of major psychiatric disease, pregnancy, unwillingness to practice contraception, significant anemia (hemoglobin <120 g/L), leukocytopenia (<3 000/μL) or thrombocytopenia (<50 000/μL)) were not included. Active hepatitis A virus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus or Ebstein-Barr virus infections were excluded by conventional laboratory tests. Findings consistent with a diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C were shown on liver biopsy during the preceding year, as determined by a single pathologist. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all treated patients.

RNA was extracted from serum samples (140 μL) using the QIAamp Viral RNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. One-fifth of the extracted material from serum was subjected to a nested RT-PCR procedure essentially as described[20].

The amount of serum HCV-RNA was determined by using the AmpliSensor System according to the instruction of the manufacturer (AmpliSensor System, BAG, Lich, Germany).

HCV genotyping was performed using the Innolipa HCV II line probe assay (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium).

Patients received subcutaneously 3 MU IFN-2a (Roferon-A, F.Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) daily. Patients with genotype 2 or 3 were treated for 24 wk, and patients with genotypes other than 2 or 3 for 48 wk. Follow-up period was 48 wk after EOT. Virological response was defined as non-detectability of serum HCV-RNA. Patients who had no virological response after 12 wk of treatment received ribavirin (10 mg/kg BW/day) additionally as described previously[21].

All patients were assessed in an outpatient setting for safety, tolerance, and efficacy at the end of weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, and every further 4th wk during treatment. When treatment was completed, patients were assessed at wk 4, 12, and 24, 36 and 48. Clinical examination, total blood cell counts and routine biochemical tests were conducted at that time. Serum was analyzed for the presence of HCV-RNA by RT-PCR before treatment, and at wk 2, 4, 12, 24, 36, and 48 during treatment for patients treated for 48 weeks and at wk 2, 4, 12, and 24 for patients treated 24 wk. During follow-up period, serum was tested for the presence of HCV-RNA at wk 4, 12, 24, 36 and 48.

Forty-six consecutive chronic HCV-infected patients (16 female, 30 male, mean age 42 years, ranging from 21 to 67 years) were enrolled. The cause for HCV transmission could be identified as blood transfusions in 17.4% (n = 8) and injection drug use in 39.1% (n = 18). Twenty patients (43.5%) had other or unknown transmission of HCV infection. Before treatment, AST levels were elevated with a mean of 27.9 U/L ranging from 12 to 67 U/L, ALT levels with a mean of 51.5 U/L ranging from 16 to 142 U/L, and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (gamma-GT) levels with a mean of 34.5 U/L ranging from 5 to 288 U/L. HCV genotypes were classified in 12 patients (26%) as 1a, in 20 (43.5%) as 1b, in 1 (2.2%) as 1a and 1b, in 1 (2.2%) as 2a and 2c, in 4 (8.7%) as 3a, in one (2.2%) as 3a and 3c, in 6 (13%) as 3c, and in 1 (2.2%) as 5a. Before treatment, the mean serum HCV-RNA level was 4.87?05 copies/mL ranging from 1?03 to 6.5×106 (SD 1.02?06). Patients showed histological diagnosis of mild chronic hepatitis (39.1%, n = 18), moderate chronic hepatitis (37%, n = 17), severe chronic hepatitis (8.7%, n = 4), cirrhosis (8.7%, n = 4), or unknown histology in 6.5% (n = 3). All patients received daily dose IFN-2a therapy as initial treatment.

Patients with genotype 2 or 3 (n = 12) showed an initial virological response rate of 100% under daily dose IFN-2a treatment. During treatment, however, three genotype 3 patients were excluded from the study due to incompliance. Thus, at that time (two patients after 4 wk and one patient after 12 wk of treatment) the drop outs were virological responders. All patients who completed therapy (n = 9) had a complete biochemical and virological response at the end of 24-wk treatment. During follow-up, after EOT three of nine patients (33.3%) developed a relapse. In these patients, initial virological response first occurred after 4 wk of treatment. The remaining six patients (66.7%) sustainingly eradicated the virus, i.e. serum viral RNA was non-detectable for at least a 48-wk period after EOT. Data of treatment response and follow-up are shown in Figure 1.

Patients with genotypes other than 2 or 3 (n = 34) showed an initial virological response rate of 23.5% (8/34) under daily dose IFN-2a treatment. These 8/34 patients (23.5%) were still virological responders at the end of 48 wk daily dose IFN-2a treatment. Two of thirty-four patients (5.9%) stopped IFN therapy due to alopecia (n = 1) and loss of weight (n = 1). During follow-up, five patients (14.7%) who had eliminated the virus at EOT relapsed, and three (8.8%) had a SVR, 48 weeks after EOT.

Twenty-four of thirty-four patients (70.6%) failed to develop an initial virological response under IFN-2a monotherapy and were treated with ribavirin (10 mg/kg BW/day) in combination as described previously[22]. Ten patients (29.4%) showed a response and 13 (38.2%) a non-response at the end of 48-wk treatment. One patient (2.9%) stopped combination therapy due to hemolysis. During follow-up, 9 (26.5%) patients with a response at EOT relapsed and only one (2.9%) patient showed a SVR, 48 weeks after EOT.

During treatment, three patients with genotype 3 had to be excluded from the study due to incompliance. At the completion of 24- and 48-wk treatment, 27 of 43 patients (62.8%) showed a virological response and 13 of 43 patients (30.2%) showed a virological non-response. In 3 of 43 patients (7%), treatment was discontinued due to alopecia (n = 1) and loss of weight (n = 1) under IFN-2a monotherapy, and due to hemolysis (n = 1) under combination therapy. Forty-eight weeks after the end of 24- and 48-wk treatment, 17 of 27 patients with a response at the end of 24- and 48-wk treatment relapsed (63%). In summary, the overall SVR rate was 23.3% (10 of 43 patients) 48 wk after EOT.

Beside the 3/43 (7%) drop outs, daily dose IFN-2a therapy (3 MU) was well tolerated. Monitoring of side effects by questioning and clinical examination revealed flu-like symptoms (e.g. pyrexia, myalgia and rigors) in one quart of cases. Mild leukocytopenia (minimum 1 800/μL) and thrombocytopenia (minimum 70 000/μL in a patient without cirrhosis and 59 000/μL in a patient with cirrhosis) was generally seen.

Side effects of additional ribavirin therapy were thyroid gland alterations (two patients with hypothyroidism and one with hyperthyroidism) and loss of weight (n = 1). Beside the one drop out due to hemolysis (minimum hemoglobin 86 g/L), decrease in hemoglobin was generally seen to a minimum of 98 g/L. There was no need of transfusion or drug dose reduction. All side effects were completely reversible within 1 mo after EOT.

In chronic HCV-infected patients, SVR rates range from 6-15% after a 6-mo course of IFN TIW to 13-25% after 12 mo of therapy[11]. One of the reasons for marginal response to IFN is its short half-life of approximately 8 h[16] which leads to wide fluctuations in the plasma concentrations of the drug during treatment period. Among patients treated with IFN TIW, an intermittent increase in viral load can be observed on treatment-free days[17]. In this prospective monocentric non-randomized study, we report our experience on 46 consecutive chronic HCV-infected patients who received 3 MU IFN-2a daily as initial regimen. Patients with genotype 2 or 3 were treated for 24 wk, and patients with genotypes other than 2 and 3 for 48 wk. Three patients with genotype 3 were excluded from the study due to incompliance. At the end of 24-wk treatment, 17/43 (39.5%) of our patients including 9/9 (100%) with genotype 2 or 3 and 8/34 (23.5%) with genotypes other than 2 or 3 eliminated the virus below the limit of detectability. In comparison, IFN 3 MU TIW for 24 wk resulted in virological response rates of 29-32% at EOT[7,8]. The rate of complete responders (23.5%) was unchanged after 48 wk of treatment in our patients with genotypes other than 2 or 3. IFN 3 MU TIW for 48 wk can induce virological response at EOT in 24-33%[7,12] of patients including different genotypes. Also, a dose of IFN 6 MIU TIW for 12 wk followed by IFN 3 MIU TIW for the remaining 36 wk resulted in a complete response rate of 25% at EOT in patients including different genotypes[22].

SVR, 48 wk after EOT resulted in 6/9 (66.7%) of our patients with genotype 2 or 3 after 24 wk 3 MU IFN daily therapy and 3/34 (8.8%) with genotypes other than 2 or 3 after 48 wk 3 MU IFN daily therapy. Compared to our results, IFN 3 MU TIW for 24 wk resulted in SVR in 2% of patients with genotype 1 and in 16% with other genotypes[7]. IFN 3 MU TIW for 48 wk resulted in SVR in 7% of patients with genotype 1 and in 29% with other genotypes[7]. In the trial of Poynard et al[12] a SVR after IFN 3 MU TIW for 48 wk was observed in 33% of patients with genotype 2 and 3 and in 11% with genotype 1, 4, 5, and 6.

Combination of IFN 3 MU TIW with ribavirin at a dosage of 1 000-1 200 mg/d for 24 wk is able to induce response rates at EOT in 53-57%[7,12]. SVR was observed in 18% of patients with genotype 1, 4, 5, or 6[12] and in 16% of patients with genotype 1[7]. Our results are difficult to compare with these results, because we added ribavirin in a lower dose (10 mg/kg BW/day) after 12 wk of daily dose IFN-2a therapy in patients with genotype other than 2 or 3 who were virological non-responders at that time. However, addition of low-dose ribavirin (10 mg/kg BW/day) is able to induce a response at 48-wk EOT in 10/24 (41.7%) initial virological non-responders to a daily dose IFN-2a monotherapy. But SVR 48 wk after EOT is low (1/10 patients), because relapse occurred in the other 9 patients. Therefore, for patients with genotypes other than 2 or 3, this regimen appears not to be sufficient. They need a combination therapy from the beginning on for a longer time or in higher dose.

Nowadays, data on pegylated IFN for treatment of HCV-infected patients are available in the literature[13,14,22]. Interestingly, pegylated IFN-2a monotherapy at a dosage of 180 μL once a week for 48 wk can induce SVR rates of 45% in patients with genotype 2 and 3[22]. Compared to these results, daily dose IFN 3 MU for 24 wk is able to induce 66.7% SVR rates in patients with genotype 2 and 3. These patients with a SVR 48 wk after EOT showed an initial virological response already after 2 wk daily dose IFN-2a monotherapy, whereas patients who relapsed after EOT showed the initial virological response first after 4 wk daily dose IFN-2a treatment. Thus, avoidance of ribavirin in a subgroup of patients with genotype 2 and 3 who showed an initial virological response early after 2 wk of IFN treatment might prevent drug associated adverse events and potential teratogenic effect in patients at child bearing age[15]. This is of particular interest, because the majority of treated patients in our study had a mean age of 42 years and 41-44 years in studies using IFN TIW monotherapy, pegylated IFN monotherapy, and combination with ribavirin[7,12-14,22]. During and 6 mo after the administration of ribavirin, at least two forms of effective contraception are advised[15]. An additional economic fact is the increased cost of ribavirin treatment in HCV patients.

Side effects are comparable with those reported for 3-6 MU TIW IFN therapy[7,12,22]. None of our patients needed dose modification due to adverse event or laboratory abnormality, but in 7% of our patients IFN therapy was discontinued due to alopecia (n = 1) and loss of weight (n = 1), and ribavirin associated hemolysis (n = 1). For comparison of our results, meta-analysis of individual patient data from European centers revealed approximately 10% withdrawal of patients during treatment[23]. In studies with 3-6 MU IFN TIW, discontinuation from therapy ranges from 10% to 14% of patients[7,12,22]. Daily dose IFN therapy does not increase the discontinuation rate in comparison to TIW IFN therapy.

In conclusion, the use of daily dose IFN-2a 3 MU for HCV-infected patients is safe and well tolerated, but is able to induce only similar SVR rates 48 wk after EOT compared to IFN TIW for patients with genotypes other than 2 or 3. Addition of low-dose ribavirin after 12 wk daily dose IFN-2a monotherapy in virological non-responders at that time can increase the initial response at EOT, but relapse rate is high during follow-up. However, in patients with genotype 2 or 3, SVR rates of 66.7% can be achieved (48 wk after EOT with 3 MU IFN-2a monotherapy daily for 24 wk). Thus, our regimen appears to be at least as effective as pegylated IFN-2a for 48 wk[22]. Noteworthy is the finding that the development of a SVR seems to be related to the time of the initial virological response. In all cases, an early initial virological response after 2 wk of IFN treatment was followed by a SVR after 24 wk daily IFN monotherapy without ribavirin. A later initial virological response after 4 wk was associated with a relapse after EOT. In accordance with our results, Bekkering et al[24] retreated 11 non-responders to previous TIW IFN therapy with daily dose IFN and found that all three sustained responders (genotype 3 in two cases and genotype 1a in one case) had undetectable plasma HCV RNA at d 14.

Recently, promising results in patients with genotype 2 and 3 treated with pegylated IFN and ribavirin combination therapy have been published[25,26]. Cornberg et al[25] reduced the duration of combination therapy with standard weight-based dose of ribavirin (1 000-1 200 mg/d) from 48- to 24-wk treatment in patients with genotype 2 and 3. This regimen resulted in a SVR of approximately 85%[25]. In March 2004, Hadziyannis et al[26] published the results of 1 311 patients treated with different regimens of short- and long-term pegylated IFN-2a (24 or 48 wk) in combination with low-dose ribavirin (800 mg/d) or standard weight-based dose of ribavirin (1 000 or 1 200 mg/d). Patients with genotype 2 or 3 were shown to be adequately treated with low-dose ribavirin in combination with pegylated IFN-2a for 24 wk[26]. Furthermore, our data suggest that there is a subgroup of patients with genotype 2 or 3 that can clear the virus with IFN-2a alone. As a result of the introduction of pegylated IFN, daily dosing of IFN has become outdated and in patients with genotype 2 or 3 HCV-infection pegylated IFN should be used as primary treatment for 24 wk with secondary addition of low-dose ribavirin (after 2 wk) only in case of failure of initial virological response 2 wk after initiation of therapy.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Farci P. Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome [Science 1989; 244: 359-362]. J Hepatol. 2002;36:582-585. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4996] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4592] [Article Influence: 131.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hoofnagle JH. Course and outcome of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S21-S29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 355] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cohen J. The scientific challenge of hepatitis C. Science. 1999;285:26-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 284] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wietzke-Braun P, Braun F, Sattler B, Ramadori G, Ringe B. Initial steroid-free immunosuppression after liver transplantation in recipients with hepatitis C virus related cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2213-2217. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatitis C and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 1997; 26: 34S-38S 9 Chemello L, Cavalletto L, Bernardinello E, Guido M, Pontisso P, Alberti A. The effect of interferon alfa and ribavirin combination therapy in naive patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatology. 1995;23:8-12. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Hoofnagle JH, Mullen KD, Jones DB, Rustgi V, Di Bisceglie A, Peters M, Waggoner JG, Park Y, Jones EA. Treatment of chronic non-A,non-B hepatitis with recombinant human alpha interferon. A preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1575-1578. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 704] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 694] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, Goodman ZD, Ling MH, Cort S, Albrecht JK. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485-1492. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2509] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2416] [Article Influence: 92.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lai MY, Kao JH, Yang PM, Wang JT, Chen PJ, Chan KW, Chu JS, Chen DS. Long-term efficacy of ribavirin plus interferon alfa in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1307-1312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 179] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chemello L, Cavalletto L, Bernardinello E, Guido M, Pontisso P, Alberti A. The effect of interferon alfa and ribavirin combination therapy in naive patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1995;23 Suppl 2:8-12. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Reichard O, Norkrans G, Frydén A, Braconier JH, Sönnerborg A, Weiland O. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of interferon alpha-2b with and without ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. The Swedish Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351:83-87. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 441] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Poynard T, Leroy V, Cohard M, Thevenot T, Mathurin P, Opolon P, Zarski JP. Meta-analysis of interferon randomized trials in the treatment of viral hepatitis C: effects of dose and duration. Hepatology. 1996;24:778-789. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 421] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Poynard T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, Niederau C, Minuk GS, Ideo G, Bain V, Heathcote J, Zeuzem S, Trepo C. Randomised trial of interferon alpha2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alpha2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group (IHIT). Lancet. 1998;352:1426-1432. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1667] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1627] [Article Influence: 62.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4736] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4508] [Article Influence: 196.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4689] [Article Influence: 213.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Keating GM, Curran MP. Peginterferon-alpha-2a (40kD) plus ribavirin: a review of its use in the management of chronic hepatitis C. Drugs. 2003;63:701-730. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Wills RJ. Clinical pharmacokinetics of interferons. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990;19:390-399. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 163] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lam NP, Neumann AU, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, Perelson AS, Layden TJ. Dose-dependent acute clearance of hepatitis C genotype 1 virus with interferon alfa. Hepatology. 1997;26:226-231. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 272] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, Layden TJ, Perelson AS. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science. 1998;282:103-107. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1604] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1426] [Article Influence: 54.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zeuzem S, Schmidt JM, Lee JH, von Wagner M, Teuber G, Roth WK. Hepatitis C virus dynamics in vivo: effect of ribavirin and interferon alfa on viral turnover. Hepatology. 1998;28:245-252. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 124] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mihm S, Hartmann H, Fayyazi A, Ramadori G. Preferential virological response to interferon-alpha 2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C infected by virus genotype 3a and exhibiting a low gamma-GT/ALT ratio. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:1256-1264. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wietzkebetaraun P, Meier V, Braun F, Ramadori G. Combination of "low-dose" ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a therapy followed by interferon alfa-2a monotherapy in chronic HCV-infected non-responders and relapsers after interferon alfa-2a monotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:222-227. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Rasenack J, Heathcote EJ, Lai MY, Gane E, O'Grady J, Reichen J, Diago M, Lin A. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1666-1672. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 883] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 933] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schalm SW, Hansen BE, Chemello L, Bellobuono A, Brouwer JT, Weiland O, Cavalletto L, Schvarcz R, Ideo G, Alberti A. Ribavirin enhances the efficacy but not the adverse effects of interferon in chronic hepatitis C. Meta-analysis of individual patient data from European centers. J Hepatol. 1997;26:961-966. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 148] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bekkering FC, Brouwer JT, Leroux-Roels G, Van Vlierberghe H, Elewaut A, Schalm SW. Ultrarapid hepatitis C virus clearance by daily high-dose interferon in non-responders to standard therapy. J Hepatol. 1998;28:960-964. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cornberg M, Hüppe D, Wiegand J, Felten G, Wedemeyer H, Manns MP. [Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with PEG-interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin: 24 weeks of therapy are sufficient for HCV genotype 2 and 3]. Z Gastroenterol. 2003;41:517-522. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, Ramadori G, Bodenheimer H Jr, Bernstein D, Rizzetto M. Peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346-355. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2216] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2085] [Article Influence: 104.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |