The International NERSH Data Pool—A Methodological Description of a Data Pool of Religious and Spiritual Values of Health Professionals from Six Continents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Building the NERSH Data Pool

3.1. Data Collection

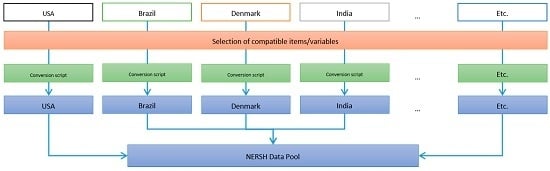

3.2. Ensuring Option Compatibility

3.2.1. Frequency of Church Attendance

3.2.2. Religious Affiliation

3.2.3. Medical Specialties

3.2.4. Occupation

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

3.4. Selection of Variables for The Data Pool

3.5. Data Management

4. The Contents of the Data Pool

5. Reliability Tests

5.1. DUREL

5.2. Religiosity of HPs

5.3. Willingness of Physicians to Interact with Patients Regarding R/S Issues

5.4. Religious Objections to Controversial Issues in Medicine

5.5. R/S as a Calling

6. Limitations

7. Strengths

8. Future Articles/Projects

- Characteristics of health professional religiosity and spirituality—descriptive statistics from six continents: Using both descriptive statistics and the scales of religious dimensions in the NERSH data pool, we want to measure the religiosity and spiritual characteristics of Health Professionals in the NERSH data pool.

- Willingness of physicians to interact with patients regarding R/S issues: Using the available scales in the data pool, we will test the hypothesis that willingness of the physicians to interact with patients regarding issues of R/S is correlated with their religiousness.

- How do the religiosity, spirituality, and personal values of psychiatrists differ from other specialties—an international comparative study from six continents: It has previously been found that psychiatrists have a lower degree of religiosity but are still open to addressing religious and spiritual issues in clinical settings. Using the R/S characteristics of the 707 psychiatrists in the data pool, we test previous findings in the now larger data pool comparing R/S characteristics between psychiatry, general practitioners, and other specialties.

- Association between personal belief systems of physicians, their nationality and their approach to controversial issues in medicine—a study from six continents: Analysis of the scale “Religious Objections to Controversial Issues in Medicine” related to religious affiliations and nationality.

- When physicians object to procedures for religious or moral reasons—experiences from six continents: Testing the hypothesis that religious physicians are more likely to legitimate withholding available treatment options for religious or moral reasons, and less likely to have attitudes obliging objecting physicians to refer patients to someone who does not object for the procedure.

9. Invitation to Collaborate

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farr A. Curlin, John D. Lantos, Chad J. Roach, Sarah A. Sellergren, and Marshall H. Chin. “Religious Characteristics of U.S. Physicians: A National Survey.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 20 (2005): 629–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr A. Curlin, Ryan E. Lawrence, Marshall H. Chin, and John D. Lantos. “Religion, Conscience, and Controversial Clinical Practices.” The New England Journal of Medicine 356 (2007): 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr A. Curlin, Chinyere Nwodim, Jennifer L. Vance, Marshall H. Chin, and John D. Lantos. “To Die, to Sleep: Us Physicians’ Religious and Other Objections to Physician-Assisted Suicide, Terminal Sedation, and Withdrawal of Life Support.” The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care 25 (2008): 112–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr A. Curlin, Shaun V. Odell, Ryan E. Lawrence, Marshall H. Chin, John D. Lantos, Keith G. Meador, and Harold G. Koenig. “The Relationship between Psychiatry and Religion among U.S. Physicians.” Psychiatric Services 58 (2007): 1193–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr A. Curlin, Sarah A. Sellergren, John D. Lantos, and Marshall H. Chin. “Physicians’ Observations and Interpretations of the Influence of Religion and Spirituality on Health.” Arch Intern Med 167 (2007): 649–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eunmi Lee, and Klaus Baumann. “German Psychiatrists’ Observation and Interpretation of Religiosity/Spirituality.” Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013 (2013): 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr A. Curlin, Marshall H. Chin, Sarah A. Sellergren, Chad J. Roach, and John D. Lantos. “The Association of Physicians’ Religious Characteristics with Their Attitudes and Self-Reported Behaviors Regarding Religion and Spirituality in the Clinical Encounter.” Medical Care 44 (2006): 446–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr A. Curlin, Lydia S. Dugdale, John D. Lantos, and Marshall H. Chin. “Do Religious Physicians Disproportionately Care for the Underserved? ” The Annals of Family Medicine 5 (2007): 353–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr A. Curlin, Ryan E. Lawrence, Shaun Odell, Marshall H. Chin, John D. Lantos, Harold G. Koenig, and Keith G. Meador. “Religion, Spirituality, and Medicine: Psychiatrists’ and Other Physicians’ Differing Observations, Interpretations, and Clinical Approaches.” The American Journal of Psychiatry 164 (2007): 1825–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaron B. Franzen. “Physicians in the USA: Attendance, Beliefs and Patient Interactions.” Journal of Religion and Health 54 (2015): 1886–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert M. Stern, Kenneth A. Rasinski, and Farr A. Curlin. “Jewish Physicians’ Beliefs and Practices Regarding Religion/Spirituality in the Clinical Encounter.” Journal of Religion and Health 50 (2011): 806–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nada A. Al-Yousefi. “Observations of Muslim Physicians Regarding the Influence of Religion on Health and Their Clinical Approach.” Journal of Religion and Health 51 (2012): 269–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eunmi Lee, Anne Zahn, and Klaus Baumann. ““Religion in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy?” A Pilot Study: The Meaning of Religiosity/Spirituality from Staff’s Perspective in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy.” Religions 2 (2011): 525–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Ramakrishnan, A. Dias, A. Rane, A. Shukla, S. Lakshmi, B. K. Ansari, R. S. Ramaswamy, A. R. Reddy, A. Tribulato, A. K. Agarwal, and et al. “Perspectives of Indian Traditional and Allopathic Professionals on Religion/Spirituality and Its Role in Medicine: Basis for Developing an Integrative Medicine Program.” Journal of Religion and Health 53 (2014): 1161–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Ramakrishnan, A. Karimah, K. Kuntaman, A. Shukla, B.K. Ansari, P.H. Rao, M. Ahmed, A. Tribulato, A. K. Agarwal, H. G. Koenig, and et al. “Religious/Spiritual Characteristics of Indian and Indonesian Physicians and Their Acceptance of Spirituality in Health Care: A Cross-Cultural Comparison.” Journal of Religion and Health 54 (2015): 649–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claudia de Souza Tomasso, Ideraldo Luiz Beltrame, and Giancarlo Lucchetti. “Knowledge and Attitudes of Nursing Professors and Students Concerning the Interface between Spirituality, Religiosity and Health.” Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 19 (2011): 1205–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Ramakrishnan, A. Rane, A. Dias, J. Bhat, A. Shukla, S. Lakshmi, B. K. Ansari, R. S. Ramaswamy, R. A. Reddy, A. Tribulato, and et al. “Indian Health Care Professionals’ Attitude Towards Spiritual Healing and Its Role in Alleviating Stigma of Psychiatric Services.” Journal of Religion and Health 53 (2014): 1800–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. Lucchetti, P. Ramakrishnan, A. Karimah, G. R. Oliveira, A. Dias, A. Rane, A. Shukla, S. Lakshmi, B. K. Ansari, R. S. Ramaswamy, and et al. “Spirituality, Religiosity, and Health: A Comparison of Physicians’ Attitudes in Brazil, India, and Indonesia.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 23 (2016): 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niels Christian Hvidt, Alex Kappel Kørup, Farr A. Curlin, Klaus Baumann, Eckhard Frick, Jens Søndergaard, Jesper Bo Nielsen, René dePont Christensen, Ryan Lawrence, Giancarlo Lucchetti, and et al. “The Nersh International Collaboration on Values, Spirituality and Religion in Medicine: Development of Questionnaire, Description of Data Pool, and Overview of Pool Publications.” Religions 7 (2016): article 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wyatt Butcher. “Spirituality, Religion and Psychiatric Practice in New Zealand: An Exploratory Study of New Zealand Psychiatrists.” Health and Social Care Chaplaincy 3 (2015): 176–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niels Christian Hvidt, Beate Mayr, Piret Paal, Eckhard Frick, Anna Forsberg, and Arndt Büssing. “For and against Organ Donation and Transplantation: Intricate Facilitators and Barriers in Organ Donation Perceived by German Nurses and Doctors.” Journal of Transplantation 2016 (2016): 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arndt Büssing, and Harold G. Koenig. “The Benefit through Spirituality/Religiosity Scale—A 6-Item Measure for Use in Health Outcome Studies.” The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 38 (2008): 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt Büssing, Julia Fischer, Almut Haller, Peter Heusser, Thomas Ostermann, and Peter F. Matthiessen. “Validation of the Brief Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale in Patients with Chronic Diseases.” European Journal of Medical Research 14 (2009): 171–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt Büssing, Thomas Ostermann, and Peter F Matthiessen. “‘Distinct Expressions of Vital Spirituality’ the Asp Questionnaire as an Explorative Research Tool.” Journal of Religion and Health, 2007, 267–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Cronbach. “Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests.” Psychometrika 16 (1951): 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold G. Koenig, and Arndt Büssing. “The Duke University Religion Index (Durel): A Five-Item Measure for Use in Epidemological Studies.” Religions 1 (2010): 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaas Sijtsma. “On the Use, the Misuse, and the Very Limited Usefulness of Cronbach’s Alpha.” Psychometrika 74 (2009): 107–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Church attendance | Religious affiliation | Occupation |

|---|---|---|

| Never

Twice a year or less Several times a year 1–3 times a month Weekly Several times a week | No affiliation (None, atheist or agnostic) Buddhist Hindu Jewish Mormon Muslim Protestant Catholic Orthodox Christian Other Christian Other Unanswered | Physician Resident Intern Midwife Nursing care Psychologist Other therapist Chaplain Teacher Student Other |

| Medical specialties | Grouped specialties |

|---|---|

| Anesthesiology | Medical subspecialty |

| Neurology | |

| General medicine | |

| Emergency medicine | |

| Dermathology | |

| Medical subspeciality | |

| Internal medicine | |

| Intensive Care | |

| Oncology and palliative care | |

| Cardiology | |

| Endocrinology | |

| Geriatrics | |

| Haematology | |

| Infectiology | |

| Nephrology | |

| General practitioner | General practitioner |

| General medicine | |

| Family practitioner | |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | Obstetrics and gynaecology |

| Ophthalmology | Surgical subspecialty |

| Surgical subspeciality | |

| Orthopedics | |

| General surgery | |

| Otorhinolaryngology | |

| Urology | |

| Pathology | Paraclinical specialty |

| Radiology | |

| Anatomy | |

| Biochemistry | |

| Pharmacology | |

| Microbiology | |

| Forensic | |

| General pediatrics | Pediatric and subspecialty |

| Pediatric subspeciality | |

| Psychiatry | Psychiatry |

| Other | Other |

| Unanswered | Unanswered |

| Observations, n | 5724 |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (CI 95%) | 41.5 (41.2–41.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 3251 (56.8%) |

| Male, n (%) | 2473 (43.2%) |

| Study \ n | Physician * | Midwife | Nursing care | Psychologist | Other therapist | Chaplain | Student | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA (RSMPP) | 1142 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1142 |

| Germany, Perinatal | 515 | 286 | 636 | 18 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 1502 |

| Germany, Turkish | 73 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 9 | 103 |

| Germany, Transplant. | 48 | 0 | 125 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 184 |

| Austria | 28 | 0 | 113 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 169 |

| Denmark | 911 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 911 |

| Germany, Freiburg | 121 | 0 | 160 | 32 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 386 |

| Saudi Arabia | 225 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 225 |

| Brazil, Nurses | 0 | 0 | 146 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 146 |

| New Zealand | 112 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 |

| India | 282 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 282 |

| Indonesia | 120 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 120 |

| Congo | 112 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 |

| Brazil | 194 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 194 |

| Total | 3883 | 286 | 1189 | 50 | 44 | 5 | 10 | 121 | 5588 |

| Study \ n | Medical | GP | Obs/gyn | Surgical | Para-clinical | Pediatric | Psychiatry | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA (RSMPP) | 314 | 304 | 80 | 118 | 45 | 147 | 100 | 34 | 1142 |

| Germany, Perinatal | 0 | 0 | 1593 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1593 |

| Germany, Turkish | 29 | 0 | 5 | 21 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 101 |

| Germany, Transplation | 116 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 182 |

| Austria | 66 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 163 |

| Denmark | 145 | 209 | 31 | 132 | 34 | 17 | 43 | 12 | 623 |

| Germany, Freiburg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 397 | 0 | 397 |

| Saudi Arabia | 70 | 73 | 31 | 30 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 225 |

| New Zealand | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 112 |

| India | 17 | 49 | 11 | 9 | 50 | 11 | 45 | 33 | 225 |

| Indonesia | 8 | 23 | 7 | 25 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 97 |

| Brazil | 146 | 0 | 10 | 26 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 194 |

| Total | 911 | 658 | 1768 | 436 | 143 | 219 | 707 | 212 | 5054 |

| Study\Scale | DUREL (5 items) | Religiosity of HPs (4 items) | Willingness of physicians to interact with patients regarding R/S issues (5 items) | Religious Objections to Controversial Issues in Medicine (5 items) | R/S as a calling (4 items) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r * | α | r * | α | r * | α | r * | α | r * | α | |

| USA | - | - | 0.65 | 0.88 | 0.53 | 0.85 | 0.06 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 0.83 |

| Germany, Perinatal | - | - | 0.63 | 0.87 | 0.29 | 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.25 | 0.73 |

| Germany, Turkish sample | 0.57 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.93 | 0.46 | 0.81 | 0.09 | 0.81 | 0.50 | 0.81 |

| Germany, Freiburg | 0.72 | 0.93 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Austria | 0.63 | 0.89 | 0.63 | 0.87 | - | - | 0.08 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 0.82 |

| Denmark | - | - | 0.68 | 0.90 | - | - | 0.01 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 0.78 |

| India | - | - | 0.38 | 0.71 | 0.27 | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 0.27 | 0.69 |

| Indonesia | - | - | 0.36 | 0.69 | 0.34 | 0.72 | 0.06 | 0.64 | 0.16 | 0.71 |

| Congo | - | - | - | - | 0.30 | 0.69 | 0.12 | 0.86 | 0.30 | 0.81 |

| Brazil | - | - | 0.46 | 0.78 | - | - | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.11 | 0.83 |

| Brazil, Nurses | 0.34 | 0.72 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.66 | 0.89 | 0.43 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 0.82 |

| Ntotal | 684 | 4107 | 1649 | 3834 | 4197 | |||||

| Factor analysis ** | ||||||||||

| Eigenvalue (%) | 3.78 (0.76) | 2.99 (0.75) | 2.73 (0.55) | 2.67 (0.53) | 2.63 (0.65) | |||||

| Factor loadings | 0.7939 0.8320 0.8850 0.9170 0.9118 | 0.8172 0.8805 0.8747 0.8857 | 0.7302 0.7217 0.7331 0.7634 0.7471 | 0.7914 0.6372 0.6259 0.7826 0.7984 | 0.5421 0.8912 0.8739 0.8835 | |||||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kørup, A.K.; Christensen, R.D.; Nielsen, C.T.; Søndergaard, J.; Alyousefi, N.A.; Lucchetti, G.; Baumann, K.; Lee, E.; Karimah, A.; Ramakrishnan, P.; et al. The International NERSH Data Pool—A Methodological Description of a Data Pool of Religious and Spiritual Values of Health Professionals from Six Continents. Religions 2017, 8, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8020024

Kørup AK, Christensen RD, Nielsen CT, Søndergaard J, Alyousefi NA, Lucchetti G, Baumann K, Lee E, Karimah A, Ramakrishnan P, et al. The International NERSH Data Pool—A Methodological Description of a Data Pool of Religious and Spiritual Values of Health Professionals from Six Continents. Religions. 2017; 8(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleKørup, Alex Kappel, René DePont Christensen, Connie Thurøe Nielsen, Jens Søndergaard, Nada A Alyousefi, Giancarlo Lucchetti, Klaus Baumann, Eunmi Lee, Azimatul Karimah, Parameshwaran Ramakrishnan, and et al. 2017. "The International NERSH Data Pool—A Methodological Description of a Data Pool of Religious and Spiritual Values of Health Professionals from Six Continents" Religions 8, no. 2: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8020024