An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used in Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characteristics of the Informants

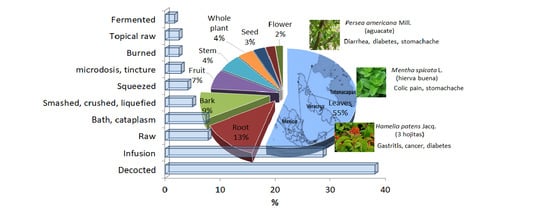

2.2. Mode of Preparation and Administration of Different Plant Parts

2.3. Use Reports, Informant’s Consensus Factor and Fidelity Level

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of the Study Area

3.2. Socio-Economic Description

3.3. Ethnobotanical Analysis

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Use Categories

3.4.2. Informants’ Consensus Factor (ICF)

3.4.3. Fidelity level (FL)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fidelis, Q.C.; Faraone, I.; Russo, D.; Aragão Catunda, F.E., Jr.; Vignola, L.; de Carvalho, M.G.; de Tommasi, N.; Milella, L. Chemical and Biological insights of Ouratea hexasperma (A. St.-Hil.) Baill: A source of bioactive compounds with multifunctional properties. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 33, 1500–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezrag, A.; Malafronte, N.; Bouheroum, M.; Travaglino, C.; Russo, D.; Milella, L.; Severino, L.; De Tommasi, N.; Braca, A.; Dal Piaz, F. Phytochemical and antioxidant activity studies on Ononis angustissima L. aerial parts: Isolation of two new flavonoids. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, T.; Saha, S.; Bisht, N. First report on the ethnopharmacological uses of medicinal plants by Monpa tribe from the Zemithang Region of Arunachal Pradesh, Eastern Himalayas, India. Plants 2017, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabesh, J.E.M.; Prabhu, S.; Vijayakumar, S. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by traditional healers in silent valley of Kerala, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Nicolás, M.; Vibrans, H.; Romero-Manzanares, A.; Saynes-Vásquez, A.; Luna-Cavazos, M.; Flores-Cruz, M.; Lira-Saade, R. Patterns of knowledge and use of medicinal plants in Santiago Camotlán, Oaxaca, Mexico. Econc. Bot. 2017, 71, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdesslem, Y.; Hachem, K.; Kahloula, K.; Slimani, M. Ethnobotanical Survey, Preliminary physico-chemical and phytochemical screening of Salvia argentea (L.) used by herbalists of the Saïda Province in Algeria. Plants 2017, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srithi, K.; Balslev, H.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Srisanga, P.; Trisonthi, C. Medicinal plant knowledge and its erosion among the Mien (Yao) in northern Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 123, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonti, M.; Vibrans, H.; Sticher, O.; Heinrich, M. Ethnopharmacology of the Popoluca, Mexico: An evaluation. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2001, 53, 1653–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bye, R.; Linares, E.; Estrada, E. Biological diversity of medicinal plants in Mexico. In Phytochemistry of Medicinal Plants; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Coneval. Consejo nacional de evaluación de la politica de desarrollo social. In La Pobreza en la Población Indígena de México, 1st ed.; Julio: Coneval, Mexico, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 1–157. ISBN 978-607-9384-9301-9382. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, T.; Canales, M.; Avila, J.G.; Duran, A.; Caballero, J.; de Vivar, A.R.; Lira, R. Ethnobotany and antibacterial activity of some plants used in traditional medicine of Zapotitlan de las Salinas, Puebla (Mexico). J Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 88, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzedowski, J. The Vegetation of Mexico; Editorial Limusa: México, Mexico, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gheno-Heredia, Y.A.; Naba-Bernal, G.; Martínez-Campos, A.R.; SánchezVera, E. Las plantas medicinales de la organización de parteras y médicos indígenas tradicionales de Ixhuatlancillo, Veracruz, Mexico, y su significancia cultural. Polibotanica 2011, 31, 199–251. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, L.; Torres, M.V.; Castillo, E.J. Flora Medicinal De Veracruz: Inventario Etnobotánico. 1; Universidad Veracruzana: Xalapa, Mexico, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Leonti, M. Traditional medicines and globalization: Current and future perspectives in ethnopharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 2013, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Barradas, C.; Eliseo Cruz-Morales, G.; Gonzalez-Gandara, C. Medicinal plants of the Ecological Reserve “Sierra of Otontepec” Township Chontla, Veracruz, Mexico. Cienciauat 2015, 9, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussy-Poma, V.; Fernández, E.; Rondevaldova, J.; Foffová, H.; Russo, D. Ethnobotanical inventory of medicinal plants used in the Qampaya District, Bolivia. B. Latinoam. Caribe Pl. 2017, 16, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Hernández, M.; Castillo-Campos, G.; Vergara Tenorio, M.D.C. Potentially useful flora from the tropical rainforest in central Veracruz, México: Considerations for their conservation. Acta. Bot. Mex. 2014, 109, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, H.; Aldosari, A.; Ali, A.; de Boer, H.J. Indigenous knowledge of folk medicines among tribal minorities in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northwestern Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 166, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunkoo, D.H.; Mahomoodally, M.F. Ethnopharmacological survey of native remedies commonly used against infectious diseases in the tropical island of Mauritius. Ethnopharmacology 2012, 143, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller-Schwarze, N.K. Antes and hoy dia: Plant knowledge and categorization as adaptations to life in Panama in the twenty-first century. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, R.J.; Pauli, G.F.; Soejarto, D.D. Factors in maintaining indigenous knowledge among ethnic communities of Manus Island. Econ. Bot. 2005, 59, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceuterick, M.; Vandebroek, I.; Torry, B.; Pieroni, A. Cross-cultural adaptation in urban ethnobotany: The Colombian folk pharmacopoeia in London. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 120, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonti, M.; Ramirez, R.F.; Sticher, O.; Heinrich, M. Medicinal flora of the Popoluca, Mexico: A botanical systematical perspective. Econ. Bot. 2003, 57, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mshana, G.; Hampshire, K.; Panter-Brick, C.; Walker, R. Urban–rural contrasts in explanatory models and treatment-seeking behaviours for stroke in Tanzania. J. Bios. Sci. 2008, 40, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teklehaymanot, T.; Giday, M.; Medhin, G.; Mekonnen, Y. Knowledge and use of medicinal plants by people around Debre Libanos monastery in Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 111, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, P.; Howes, M.J.R.; Edwards, S.E. Data on medicinal plants used in Central America to manage diabetes and its sequelae (skin conditions, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, urinary problems and vision loss). Data Brief 2016, 7, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frei, B.; Baltisberger, M.; Sticher, O.; Heinrich, M. Medical ethnobotany of the Zapotecs of the Isthmus-Sierra (Oaxaca, Mexico): Documentation and assessment of indigenous uses. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1998, 62, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Domínguez, F.; Maldonado-Miranda, J.J.; Castillo-Pérez, L.J.; Carranza-Álvarez, C.; Solano, E.; Isiordia-Espinoza, M.A.; del Carmen Juárez-Vázquez, M.; Zapata-Morales, J.R.; Argueta-Fuertes, M.A. Use of medicinal plants by health professionals in Mexico. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 198, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, P.; Howes, M.-J.R.; Edwards, S.E. Medicinal plants used in the traditional management of diabetes and its sequelae in Central America: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 184, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Amsterdam, J.D.; Li, Y.; Soeller, I.; Rockwell, K.; Mao, J.J.; Shults, J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral Matricaria recutita (chamomile) extract therapy of generalized anxiety disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharm. 2009, 29, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arqueta-Villamar, A.; Cano-Asseleih, L.; Rodarte, M. Atlas de las Plantas de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana; Instituto Nacional Indigenista: Ciudad, Mexico, 1994; p. 348. [Google Scholar]

- López, Z.; Núñez-Jinez, G.; Avalos-Navarro, G.; Rivera, G.; Salazar-Flores, J.; Ramírez, J.A.; Ayil-Gutiérrez, B.A.; Knauth, P. Antioxidant and cytotoxicological effects of Aloe vera food supplements. J. Food Qual. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador Gomez-Rivera, A.; Yuridia Lopez, C.; Martinez Burgos, M.; Cachon Mis, X.J. Morphological characterization of isolated endophyte fungi from Hamelia patens Jacq. y Lantana camara L. in Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Teor. Y Prax. 2016, 12, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surana, A.R.; Wagh, D.R.. GC-MS profiling and antidepressant-like effect of the extracts of Hamelia patens in animal model. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2017, 12, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imafidon, K.; Amaechina, F. Effects of aqueous seed extract of Persea americana Mill.(avocado) on blood pressure and lipid profile in hypertensive rats. Adv. Biol. Res. 2010, 4, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Balick, M.J.; Arvigo, R.; Romero, L. The development of an ethnobiomedical forest reserve in Belize: Its role in the preservation of biological and cultural-diversity. Conserv. Biol. 1994, 8, 316–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Zepeda, R.E.; Valenzuela-Antelo, O.; Garibay-Escobar, A.; Velázquez-Contreras, C.; Navarro-Navarro, M.; Contreras, L.R.; Corral, O.L.; Lozano-Taylor, J. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in a region of northwest Mexico. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2011, 17, 787–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umair, M.; Altaf, M.; Abbasi, A.M. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Hafizabad district, Punjab-Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, A.F.; Ruiz-Ramírez, J. Grado de marginación en comunidades indígenas en Veracruz, México: Una percepción errónea de pobreza. Contrib. Cienc. Soc. 2014, 2014, 2. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. México en cifras. In Información Nacional Por Entidad Federativa y Municipios; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía de México (INEGI): Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- de México, E.D.L.M. Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. Gobierno del Estado de México, State Government of Mexico (Mexico). 2005. Available online: www.e-local.gob.mx/ (accessed on 25 February 2008).

- Ferreira, F.S.; Brito, S.V.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Saraiva, A.A.; Almeida, W.O.; Alves, R.R. Animal-based folk remedies sold in public markets in Crato and Juazeiro do Norte, Ceará, Brazil. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2009, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appiah, K.; Oppong, C.; Mardani, H.; Omari, R.; Kpabitey, S.; Amoatey, C.; Onwona-Agyeman, S.; Oikawa, Y.; Katsura, K.; Fujii, Y. Medicinal Plants Used in the Ejisu-Juaben Municipality, Southern Ghana: An Ethnobotanical Study. Medicines 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 45 Gerbino, A.; Schena, G.; Milano, S.; Milella, L.; Franco Barbosa, A.; Armentano, F.; Procino, G.; Svelto, M.; Carmosino, M. Spilanthol from Acmella oleracea lowers the intracellular levels of cAMP impairing NKCC2 phosphorylation and water channel AQP2 membrane expression in mouse kidney. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, D.; Malafronte, N.; Frescura, D.; Imbrenda, G.; Faraone, I.; Milella, L.; Fernandez, E.; De Tommasi, N. Antioxidant activities and quali-quantitative analysis of different Smallanthus sonchifolius [(Poepp. and Endl.) H. Robinson] landrace extracts. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 1673–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovesná, J.; Kučera, L.; Horníčková, J.; Svobodová, L.; Stavělíková, H.; Velíšek, J.; Milella, L. Diversity of S- alk(en)yl cysteine sulphoxide content within a collection of garlic (Allium sativum L.) and its association with the morphological and genetic background assessed by AFLP. Sci. Hort. 2011, 129, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Background Characteristic | No | % | Annual Expenditure (Mexican Pesos, $) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | Rural | 26 | 31 | 160 |

| Urban | 59 | 69 | 200 | |

| Gender | Female | 40 | 47 | 174 |

| Male | 45 | 53 | 200 | |

| Age | >20 | 2 | 2 | 200 |

| 21–30 | 13 | 15 | 233 | |

| 31–40 | 12 | 14 | 183 | |

| 41–50 | 16 | 19 | 173 | |

| 51–60 | 20 | 24 | 210 | |

| 61–70 | 14 | 17 | 120 | |

| 71–85 | 8 | 9 | 225 | |

| Occupation | Farmer | 9 | 11 | 114 |

| Housewife | 21 | 25 | 210 | |

| Seller | 4 | 5 | 50 | |

| Teacher | 2 | 2 | 200 | |

| Worker | 40 | 47 | 181 | |

| Other | 9 | 10 | 222 | |

| Family | Scientific Name | Voucher Specimen | Common Name | Origin | Plant Part Used | Ailments | Category | Preparation Mode | Detailed Administration | UR | FL (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | Beta vulgaris L. | PA-01 | betabel | Ex | root | intestinal worms | G | fresh | raw | 1 | 100.0 |

| stomach ache | G | fresh | infusion | 1 | |||||||

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium cepa L. | PA-02 | cebolla morada | Ex | root | erection | D | fresh | crushed | 1 | 66.7 |

| kidney problem | C | fresh | crushed | 1 | |||||||

| veterinary fever in chicken | R | fresh | smashed | 4 | |||||||

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium sativum L. | PA-03 | ajo | Ex | root | blood circulation | B | fresh | infusion | 3 | 26.3 |

| cold | A | fresh | infusion | 2 | |||||||

| grains in the skin | O | fresh | bath | 2 | |||||||

| ajo con alcohol | root | liver problems | N | fresh | microdosis | 1 | |||||

| rheumatism | E | fresh | tincture | 5 | |||||||

| snake bites | M | fresh | tincture | 1 | |||||||

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium sativum L. | ajo con (with) aguacate | leaves | stomach ache | G | fresh | infusion | 3 | |||

| tooth pain | L | fresh | raw | 2 | |||||||

| Anacardiaceae | Spondias mombin L. | PA-04 | caña con jobo, durazno y piña | N | bark | alcoholic drink | R | dry | fermented | 1 | 66.7 |

| flu | A | dry | decocted | 6 | |||||||

| tooth pain | L | dry | decocted | 2 | |||||||

| Annonaceae | Annona glabra L. | PA-05 | anona | N | leaves | diarrhoea | G | fresh | infusion | 7 | 57.9 |

| fruit | drink | S | fresh | 3 | |||||||

| leaves | stomach ache | G | fresh | infusion | 4 | ||||||

| fruit | to have children | D | dry | squeezed | 3 | ||||||

| leaves | to have children | D | fresh | infusion | 2 | ||||||

| Annonaceae | Mangifera indica L | PA-06 | mango | Ex | seed | diarrhoea | G | fresh | decocted | 4 | 100.0 |

| Apiaceae | Arracacia atropurpúrea | PA-07 | comino | N | leaves | diarrhoea | G | dry | decocted | 6 | 100.0 |

| Apiáceas | Annona muricata | PA-08 | guanabana | N | leaves | cancer | I | fresh | infusion | 7 | 34.4 |

| leaves | diabetes | H | fresh | infusion | 6 | ||||||

| leaves | high pressure | B | fresh | infusion | 11 | ||||||

| Apiáceas | Apium graveolens L. | apio | Ex | stem | cholesterol | B | fresh | liquefied | 8 | 100.0 | |

| Apocynaceae | Pentalinon andrieuxii (Müll.Arg.) B.F.Hansen & Wunderlin | PA-09 | guaco enredadera | N | root | snake bites | M | dry | tincture | 13 | 100.0 |

| Apocynaceae | Rauvolfia tetraphylla L. | PA-10 | cancerina | N | leaves | cancer | I | fresh | infusion | 11 | 100.0 |

| Arecaceae | Cocos nucifera L. | PA-11 | coco and caña morada | Ex | leaves | blood circulation | B | fresh | raw | 3 | 68.8 |

| chinkunguya | P | fresh | raw | 5 | |||||||

| dengue | P | fresh | raw | 6 | |||||||

| bark | stop bleeding in the parthum | D | fresh | decocted | 2 | ||||||

| Arecáceas | Acrocomia aculeata (Jacq.) Lodd. ex Mart. | PA-12 | coyol redondo palma | N | root | diabetes | H | dry | infusion | 3 | 50.0 |

| bark | eyes problem | Q | dry | decocted | 3 | 50.0 | |||||

| Asclepiadaceae | Asclepias curassavica L. | PA-13 | hierva del sapo | N | leaves | cancer | I | fresh | decocted | 16 | 59.,3 |

| leaves | diabetes | H | dry | infusion | 5 | ||||||

| leaves | kidney problem | C | fresh | decocted | 6 | ||||||

| Asteraceae | Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. | PA-14 | estafiate | N | stem | cholesterol | B | fresh | infusion | 12 | 100.0 |

| Asteraceae | Calea ternifolia Oliv. ex Thurn | PA-15 | zacate chichi | N | leaves, stem, flower | bile | G | fresh | infusion | 5 | 70.6 |

| diabetes | H | fresh | infusion | 12 | |||||||

| Asteraceae | Cyclolepis genistoides D.Don | PA-16 | palo azul | Ex | bark | kidney problem | C | dry | decocted | 4 | 100.0 |

| Asteraceae | Gnaphalium viscosum Kunth | PA-17 | gordolobo | N | whole plant | cough | A | fresh | infusion | 2 | 100.0 |

| Asteraceae | Matricaria chamomilla L. | PA-18 | manzanilla | Ex | whole plant | colic pain | D | fresh | decocted | 16 | 47.1 |

| leaves | eyes problem | Q | fresh | bath | 4 | ||||||

| whole plant | stomach ache | G | fresh | decocted | 14 | ||||||

| Asteraceae | Parthenium hysterophorus L. | PA-19 | chuchullate o tres hojitas | N | stem | anaemia | B | fresh | decocted | 1 | 53.8 |

| leaves | diabetes | H | fresh | infusion | 7 | ||||||

| leaves | wounds | O | fresh | bath | 2 | ||||||

| wounds | O | fresh | decocted | 3 | |||||||

| Asteraceae | Tagetes erecta L. | PA-20 | flor de muerto | N | root | stomach ache | G | dry | decocted | 6 | 100.0 |

| Asteraceae | Verbesina persicifolia D.C | PA-21 | huichin | N | leaves | diabetes | H | fresh | infusion | 9 | 39.1 |

| leaves | gastritis | G | fresh | decocted | 1 | ||||||

| root | high pressure | B | fresh | decocted | 9 | 39.1 | |||||

| root | inflammation | E | fresh | bath | 4 | ||||||

| Bignoniaceae | Parmentiera aculeata (Kunth) Seem. | PA-22 | chote, chiote | N | flower | veterinary uses | R | fresh | decocted | 7 | 50.0 |

| kidney problem | C | fresh | decocted | 7 | |||||||

| Bignoniaceae | Tecoma stans (L.) Juss. ex Kunth | PA-23 | tronadora (hoja de san pedro) | N | leaves | infection in skin | O | fresh | burned | 2 | 100.0 |

| Brassicaceae | Nasturtium officinale R. Br. | PA-24 | berros | N | leaves | anaemia | B | fresh | bath | 3 | 100.0 |

| Burseraceae | Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg. | PA-25 | chaca | leaves | fever | P | fresh | cataplasm | 45 | 100.0 | |

| Cactaceae | Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. | PA-26 | Nopal, pepino and cascara | N | leaves | cholesterol | B | fresh | liquefied | 2 | 66.7 |

| clean stomach | G | fresh | liquefied | 8 | |||||||

| diabetes | H | fresh | decocted | 2 | |||||||

| Cannabacea | Cannabis sativa L. | PA-27 | marihuana | Ex | whole plant | rheumatism | E | fresh | tincture | 9 | 100.0 |

| Cannabaceae | Trema micrantha (L) Blume | PA-28 | puam | N | leaves | chicken pox | P | fresh | bath | 8 | 100.0 |

| measles | P | fresh | bath | 6 | |||||||

| Caricaceae | Carica papaya L. | PA-29 | papaya | stem | pain in ears | Q | fresh | burned | 5 | 100.0 | |

| Chenopodiaceae | Chenopodium ambrosioides | PA-30 | epasote | N | leaves | intestinal worms | G | fresh | infusion | 13 | 100.0 |

| stomach ache | G | fresh | infusion | 12 | |||||||

| Commelinaceae | Tradescantia spathacea Sw. | PA-31 | barquilla, maguey morado | N | leaves | grains in the mouth | L | fresh | squeezed | 3 | 38.7 |

| kidney problem | C | fresh | infusion | 8 | |||||||

| respiratory system | A | fresh | infusion | 8 | |||||||

| wounds | O | fresh | burned | 1 | |||||||

| skin infection | O | fresh | bath | 3 | |||||||

| wounds and bruises | O | fresh | cataplasm | 8 | |||||||

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita pepo L. | PA-32 | calabaza | N | latex | scratches, wounds | O | fresh | squeezed | 4 | 100.0 |

| Cucurbitaceae | Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw. | PA-33 | chayote | N | fruit | cholesterol | B | fresh | decocted | 12 | 100.0 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Cnidoscolus chayamansa Mc Vaugh | PA-34 | chaya | N | leaves | high pressure | B | fresh | decocted | 7 | 100.0 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Cnidoscolus tubulosus (Müll.Arg.) I.M.Johnst. | PA-35 | hortiga macho con espina | N | root | kidney problem | C | dry | decocted | 5 | 61.1 |

| stem | kidney problem | C | fresh | infusion | 6 | ||||||

| latex | tooth pain | L | fresh | raw | 7 | ||||||

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia hirta L. | PA-36 | riñonina | N | leaves | kidney problem | C | fresh | infusion | 6 | 100.0 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Jatropha curcas L. | PA-37 | piñon | N | latex | bleeding of the gums, | L | fresh | topical raw | 4 | 57.1 |

| leaves | grains | O | fresh | bath | 1 | ||||||

| latex | herpes | P | fresh | topical raw | 2 | ||||||

| Fabaceae | Bauhinia divaricata L. | PA-38 | pata de vaca | N | leaves | diabetes | H | fresh | infusion | 4 | 44.4 |

| diarrhoea | G | fresh | infusion | 3 | |||||||

| Mixed with crushed rice | whole plant | dysentery | G | fresh | decocted | 1 | |||||

| leaves | grains in the skin | O | fresh | bath | 1 | ||||||

| Fabaceae | Cassia fistula L. | PA-39 | hojasen | Ex | leaves | colitis | G | fresh | infusion | 3 | 100.0 |

| Fabaceae | Erythrina caribaea Krukoff & Barneby | PA-40 | pichoco | N | bark | push delivering in parthum | D | fresh | decocted | 2 | 100.0 |

| Fabaceae | Eysenhardtia polystachya (Ortega) Sarg | PA-41 | tarai (palo azul) | N | bark | kidney problem | C | dry | infusion | 5 | 100.0 |

| Fabaceae | Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp | PA-42 | cocohuite | N | leaves | fever | P | fresh | tincture | 2 | 100.0 |

| Fabaceae | Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit | PA-43 | guaje | N | fruit | intestinal worms | G | fresh | raw | 4 | 100.0 |

| Geraniaceae | Pelargonium spp. | PA-44 | malva con hortiga | Ex | leaves | chicken pox | P | fresh | decocted | 1 | 50.0 |

| grains | O | fresh | decocted | 1 | |||||||

| Lamiaceae | Mentha spicata L. | PA-45 | hierva buena | Ex | leaves | colic pain | D | fresh | infusion | 14 | 57.6 |

| stomach ache | G | fresh | decocted | 19 | |||||||

| Lamiaceae | Ocimum basilicum L. | PA-46 | albacahar | N | leaves | anxiety | F | fresh | raw | 7 | 36.0 |

| bad wind | S | fresh | raw | 3 | |||||||

| dizzy | Q | fresh | infusion | 9 | |||||||

| evil eye | S | fresh | bath | 4 | |||||||

| high pressure | B | fresh | infusion | 1 | |||||||

| nausea | G | fresh | infusion | 1 | |||||||

| Lamiaceae | Salvia spp. | PA-47 | salvia | En | leaves | spasm | E | fresh | decocted | 2 | 100.0 |

| Lauraceae | Cinnamomum verum J.Presl | PA-48 | mango con canela | Ex | leaves | abortive | D | fresh | decocted | 2 | 58.3 |

| chinkunguya | P | fresh | decocted | 2 | |||||||

| cough | A | fresh | decocted | 1 | |||||||

| colic pain | D | fresh | decocted | 5 | |||||||

| drink | S | fresh | decocted | 2 | |||||||

| Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill. | PA-49 | aguacate | N | seed | abortive | D | fresh | decocted | 5 | 86.2 |

| Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill. | aguacate oloroso | N | leaves | diarrhoea | G | fresh | infusion | 19 | ||

| seed | kidney problem | C | fresh | liquefied | 3 | ||||||

| leaves | nausea | G | fresh | infusion | 2 | ||||||

| leaves | stomach ache | G | fresh | infusion | 29 | ||||||

| Loranthaceae | Struthanthus crassipes (Oliver) Eichl. | PA-50 | secapalo | En | leaves | grains | O | fresh | decocted | 7 | 53.3 |

| kidney problem | C | fresh | decocted | 7 | |||||||

| wounds | O | fresh | bath | 1 | |||||||

| Malvaceae | Guazum aulmifolia Lam. | PA-51 | guazima | N | bark | colitis | G | dry | decocted | 5 | 61.9 |

| bark | diabetes | H | dry | decocted | 4 | ||||||

| bark | diarrhoea | G | dry | decocted | 4 | ||||||

| fruit | drink | S | fresh | squeezed | 2 | ||||||

| bark | stomach ache | G | dry | decocted | 4 | ||||||

| leaves | veterinary | R | fresh | raw | 2 | ||||||

| Malvaceae | Heliocarpus appendiculatus Turcz. | PA-52 | jonote | N | latex | wounds | O | dry | topical raw | 4 | 100.0 |

| Malvaceae | Sida rhombifolia L. | PA-53 | malva and albacahar | N | leaves | bad wind | S | fresh | raw | 1 | 100.0 |

| stem | ritual | S | fresh | raw | 4 | ||||||

| Malvaceae | Sphaeralcea angustifolia (Cav.) G.Don | PA-54 | hierva del negro | N | whole plant | bad wind | S | fresh | raw | 15 | 100.0 |

| Meliaceae | Azadirachta indica A. Juss. | PA-55 | neem | Ex | fruit | diabetes | H | fresh | infusion | 18 | 100.0 |

| Meliaceae | Cedrela odorata L. | PA-56 | cedro | N | bark | abortive | D | dry | decocted | 4 | 75.0 |

| bark | fever | P | dry | decocted | 1 | ||||||

| leaves | inflammation | E | fresh | decocted | 1 | ||||||

| bark | problems in trying to have children | D | dry | decocted | 2 | ||||||

| Meliaceae | Melia azedarach L. | PA-57 | piocha | Ex | leaves | diabetes | H | fresh | infusion | 8 | 100.0 |

| Monimiaceae | Peumus boldus Molina | PA-58 | boldo | Ex | leaves | colitis | G | fresh | infusion | 4 | 100.0 |

| Moraceae | Morus celtidifolia Kunth | PA-59 | mora | N | leaves | chinkunguya | P | fresh | decocted | 2 | 66.7 |

| leaves | tooth pain | L | fresh | raw | 1 | ||||||

| Moringaceae | Moringa oleifera Lam. | PA-60 | moringa | Ex | leaves | cancer | I | fresh | decocted | 1 | 85.7 |

| leaves | diabetes | H | fresh | decocted | 6 | ||||||

| Musaceae | Musa spp. | PA-61 | platano | Ex | bark | respiratory system | A | fresh | decocted | 2 | 77.8 |

| bark | tuberculosis | P | fresh | fermented | 7 | ||||||

| Myrsinaceae | Ardisia compressa Kunth | PA-62 | capulin and nona | N | leaves | stomach ache | G | fresh | infusion | 5 | 62.5 |

| leaves | wounds | O | fresh | bath | 3 | ||||||

| Myrtaceae | Eucalyptus globulus Labill | PA-63 | eucalipto | Ex | leaves | bronchitis | A | fresh | decocted | 3 | 100.0 |

| Myrtaceae | Pimenta dioica(L.) Merr. | PA-64 | pimienta | Ex | leaves | flu | A | fresh | decocted | 3 | 100.0 |

| Myrtaceae | Psidium guajava L. | PA-65 | guayaba | N | leaves | diarrhoea | G | dry | decocted | 16 | 53.3 |

| bark | flu | A | dry | decocted | 14 | ||||||

| Myrtaceae | Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & Perry | PA-66 | clavo | Ex | seed | tooth pain | L | dry | topical raw | 5 | 100.0 |

| Nyctaginaceae | Bougainville aglabra Choisy | PA-67 | bugambilia | Ex | flower | cough | A | fresh | infusion | 19 | 100.0 |

| Orchidaceae | Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews | PA-68 | vainilla | N | fruit | drink | S | fresh | fermented | 2 | 72.7 |

| fruit | drink | S | fresh | raw | 6 | ||||||

| fruit | menopause | D | fresh | tincture | 1 | ||||||

| leaves | menopause | D | fresh | decocted | 2 | ||||||

| Papaveraceae | Fumaria officinalis L. | PA-69 | Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) | Ex | leaves | wounds | O | fresh | bath | 3 | 100.0 |

| Passifloraceae | Passiflora coriacea Juss. | PA-70 | hierva del murcielago | N | leaves | kidney problem | C | fresh | decocted | 6 | 100.0 |

| Pedaliaceae | Sesamum indicum L. | PA-71 | ajonjoli | Ex | seed | breastfeeding | D | dry | decocted | 15 | 100.0 |

| Piperaceae | Peperomia granulosa Trel. | PA-72 | gordonzillo (acoyo) | N | root | breastfeeding | D | fresh | decocted | 5 | 53.1 |

| stems | menstruation | D | fresh | decocted | 4 | ||||||

| root | to have children | D | fresh | decocted | 8 | ||||||

| leaves | cirrhosis | N | fresh | infusion | 1 | ||||||

| leaves | rheumatism | E | fresh | burned | 9 | ||||||

| acoyo (gordonsillo) and ajo | leaves | respiratory system | A | fresh | infusion | 5 | |||||

| Piperaceae | Piper sanctum (Miq.) Schltdl. ex C.DC. | PA-73 | hierva santa | N | leaves | clean baby and post-parthum | D | fresh | decocted | 2 | 100.0 |

| Plantaginaceae | Plantago major L. | PA-74 | llanten | Ex | leaves | skin problems | O | fresh | decocted | 15 | 100.0 |

| Poaceae | Cymbopogon citratu Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf | PA-75 | zacate limon | Ex-invader | leaves | drink | S | fresh | 7 | 100.0 | |

| Poaceae | Pachystachys spicata (Ruiz & Pav.) Wassh. | PA-76 | mohuite | N | stem | bad wind | S | fresh | 1 | 70.6 | |

| leaves | epilepsy | F | fresh | decocted | 3 | ||||||

| kidney problem | C | fresh | decocted | 12 | |||||||

| nausea | G | fresh | infusion | 1 | |||||||

| Poaceae | Phalaris canariensis L. | PA-77 | alpistle | Ex | seed | diabetes | H | fresh | liquefied | 9 | 100.0 |

| Poaceae | Zea maiz L. | PA-78 | maiz morado | N | seed | alcoholic drink | S | fresh | fermented | 3 | 82.4 |

| pelo de maiz | fruit | kidney problem | C | fresh | infusion | 14 | |||||

| Portulacaceae | Portulaca oleraceae L. | PA-79 | verdolaga | N | leaves | blood circulation | B | fresh | burned | 2 | 100.0 |

| Rosaceae | Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl. | PA-80 | nispero | Ex | leaves | kidney problem | C | fresh | decocted | 2 | 100.0 |

| Rosaceae | Prunus domestica L. | PA-81 | ciruela | Ex | leaves | rash and grains | O | fresh | smashed | 4 | 66.7 |

| smallpox | P | fresh | bath | 2 | |||||||

| Rubiaceae | Hamelia patens Jacq. | PA-82 | tres hojitas | N | leaves | anaemia | B | fresh | infusion | 3 | 23.4 |

| blood circulation | B | fresh | decocted | 7 | |||||||

| breastfeeding | D | fresh | burned | 6 | |||||||

| cancer | I | dry | decocted | 9 | |||||||

| colitis | G | fresh | decocted | 4 | |||||||

| diabetes | H | fresh | decocted | 7 | |||||||

| diabetes | H | fresh | infusion | 11 | |||||||

| gastritis | G | fresh | infusion | ||||||||

| gastritis | G | fresh | decocted | 8 | |||||||

| high pressure | B | fresh | infusion | 1 | |||||||

| menstruation | D | fresh | decocted | 2 | |||||||

| root | respiratory system | A | dry | decocted | 7 | ||||||

| skin problems, fungus | O | fresh | squeezed | 2 | |||||||

| ulcers | G | fresh | decocted | 5 | |||||||

| wounds | O | fresh | bath | 5 | |||||||

| Rubiaceae | Morinda citrifolia L. | PA-83 | noni | Ex | fruit | diabetes | H | fresh | liquefied | 10 | 83.3 |

| heart problems | B | fresh | squeezed | 2 | |||||||

| Rutaceae | Casimiroa edulis La Llave | PA-84 | zapote blanco | N | leaves | cholesterol | B | fresh | infusion | 3 | 30.0 |

| latex | gum | L | dry | raw | 2 | ||||||

| bark | diabetes | H | dry | decocted | 1 | ||||||

| leaves | fever | P | fresh | infusion | 2 | ||||||

| bark | kidney problem | C | dry | decocted | 2 | ||||||

| Rutaceae | Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle | PA-85 | azares de naranjo | Ex | leaves | anxiety | F | fresh | decocted | 3 | 100.0 |

| Rutaceae | Citrus× aurantium L. | PA-86 | naranja cucha | Ex | leaves | anxiety | F | fresh | decocted | 9 | 64.3 |

| cough | A | fresh | decocted | 4 | |||||||

| naranja, papaya, limon, nopal | fruit | diabetes | H | fresh | liquefied | 1 | |||||

| Rutaceae | Citrus limetta Risso | PA-87 | lima chichi | Ex | fruit | high pressure | B | fresh | decocted | 3 | 75.0 |

| infection in the eyes | Q | fresh | squeezed | 9 | |||||||

| Rutaceae | Citrus medica L. | PA-88 | limon | N | fruit | cough | A | fresh | infusion | 14 | |

| Rutaceae | Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | PA-89 | naranja | Ex | leaves | anxiety | F | fresh | infusion | 6 | 54.5 |

| flu | A | fresh | infusion | 5 | |||||||

| Rutaceae | Murraya paniculata (L.) Jack | PA-90 | limonaria | Ex | leaves | diabetes | H | fresh | squeezed | 2 | 66.7 |

| tooth pain | L | fresh | decocted | 1 | |||||||

| Rutaceae | Ruta graveolens L. | PA-91 | ruda | Ex | leaves | colitis | G | fresh | infusion | 3 | 43.8 |

| evil eye | S | fresh | raw | 3 | |||||||

| gastritis | G | fresh | infusion | 4 | |||||||

| high pressure | B | fresh | infusion | 4 | |||||||

| menstruation | D | fresh | infusion | 8 | |||||||

| pain in ears | Q | fresh | infusion | 3 | |||||||

| abortive | D | fresh | infusion | 6 | |||||||

| pain in the chest | A | fresh | infusion | 1 | |||||||

| Sapotaceae | Manilkara chicle (Pittier) Gilly | PA-92 | zapote chico and guia del chayote | N | leaves | cholesterol | B | fresh | infusion | 4 | 57.1 |

| diabetes | H | fresh | infusion | 1 | |||||||

| high pressure | B | fresh | infusion | 2 | |||||||

| Sapotaceae | Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H.E. Moore & Stearn. | PA-93 | zapote rebentador | N | bark | diabetes | H | dry | decocted | 4 | 57.1 |

| fruit | diarrhoea | G | fresh | squeezed | 2 | ||||||

| leaves | nausea | G | fresh | decocted | 1 | ||||||

| Smilacaceae | Smilax mollis Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. | PA-94 | cocolmecate (bejuco enredadera) | N | root | diabetes | H | dry | decocted | 4 | 57.1 |

| root | gastritis | G | dry | decocted | 1 | ||||||

| bark | loss weight | B | dry | decocted | 2 | ||||||

| Solanaceae | Physalis ixocarpa Brot. ex Hornem | PA-95 | tomate verde | N | leaves | kidney problem | C | fresh | infusion | 4 | 100.0 |

| Urticaceae | Cecropia obtusifolia Bertol. | PA-96 | hormiguillo (nihuiya) | N | bark | diabetes | H | dry | decocted | 2 | 100.0 |

| Verbenaceae | Lippia duartei Moldenke | PA-97 | hierva dulce | N | whole plant | diabetes | H | dry | decocted | 1 | 50.0 |

| leaves | diarrhoea | G | dry | decocted | 1 | ||||||

| Verbenaceae | Lippia graveolens Kunth | PA-98 | oregano | N | leaves | respiratory system | A | dry | infusion | 4 | 100.0 |

| Xanthorrhoeaceae | Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. | PA-99 | savila | Ex | leaves | gastritis | G | fresh | raw | 7 | 33.3 |

| hair problems | Q | fresh | smashed | 6 | |||||||

| inflammation | E | fresh | topical raw | 3 | |||||||

| whole plant | ulcers | G | fresh | infusion | 3 | ||||||

| wounds | O | fresh | topical raw | 11 | |||||||

| anaemia | B | fresh | infusion | 1 | |||||||

| chinkunguya | P | fresh | infusion | 2 | |||||||

| Zingiberaceae | Costus spicatus (Jacq.) Sw. | PA-100 | caña de jabali | N | stem | kidney problem | C | dry | infusion | 21 | 95.5 |

| caña de jabali con raiz de chiote | root | hepatitis | N | dry | decocted | 1 | |||||

| Zingiberaceae | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | PA-101 | gengibre | Ex | root | anaemia | B | fresh | decocted | 1 | 54.5 |

| blood circulation | B | fresh | decocted | 2 | |||||||

| clean the blood | B | fresh | raw | 3 | |||||||

| colic pain | D | fresh | decocted | 1 | |||||||

| stomach ache | G | fresh | decocted | 1 | |||||||

| intestinal worm | G | fresh | decocted | 2 | |||||||

| inflammation | E | fresh | decocted | 1 |

| N° | AILMENT CATEGORIES | N° SPECIES | N° of UR | % UR | ICF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Respiratory system disorders | 17 | 100 | 7.89 | 0.84 |

| B | Blood-cardiovascular disorders | 21 | 112 | 8.83 | 0.82 |

| C | Kidney disorders | 17 | 119 | 9.38 | 0.86 |

| D | Genital-urinary disorders and childcare | 17 | 118 | 9.31 | 0.86 |

| E | Skeleton-muscular system disorders | 8 | 34 | 2.68 | 0.79 |

| F | Nervous system disorders | 5 | 28 | 2.21 | 0.85 |

| G | Gastro-intestinal disorders | 29 | 247 | 19.48 | 0.89 |

| H | Endocrinal disorders | 23 | 137 | 10.80 | 0.84 |

| I | Oncology | 5 | 44 | 3.47 | 0.91 |

| L | Dental care | 9 | 27 | 2.13 | 0.69 |

| M | Poisonous bites | 2 | 14 | 1.10 | 0.92 |

| N | Liver disorders | 3 | 3 | 0.24 | 0.00 |

| O | Skin disorders | 17 | 83 | 6.55 | 0.80 |

| P | Fever and infective diseases | 13 | 93 | 7.33 | 0.87 |

| Q | Ear-eye-hair disorders | 7 | 39 | 3.08 | 0.84 |

| R | Veterinary uses | 4 | 14 | 1.10 | 0.77 |

| S | Different uses | 11 | 56 | 4.42 | 0.82 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lara Reimers, E.A.; C., E.F.; Lara Reimers, D.J.; Chaloupkova, P.; Zepeda del Valle, J.M.; Milella, L.; Russo, D. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used in Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico. Plants 2019, 8, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8080246

Lara Reimers EA, C. EF, Lara Reimers DJ, Chaloupkova P, Zepeda del Valle JM, Milella L, Russo D. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used in Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico. Plants. 2019; 8(8):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8080246

Chicago/Turabian StyleLara Reimers, Eduardo Alberto, Eloy Fernández C., David J. Lara Reimers, Petra Chaloupkova, Juan Manuel Zepeda del Valle, Luigi Milella, and Daniela Russo. 2019. "An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used in Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico" Plants 8, no. 8: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8080246