Governing for Child-Friendliness? Perspectives on Children as Users Among Swedish and Danish Urban Open Space Managers

- 1Department of Landscape Architecture, Planning and Management, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Alnarp, Sweden

- 2Department of Architecture and Built Environment, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

Despite the acknowledged importance of outdoor environment quality in supporting children's health and well-being, little is known about how contemporary urban open space management caters for children. In this study, Swedish (n = 54) and Danish (n = 25) local governments were surveyed regarding how they manage urban open space for children, e.g., through a child-centered perspective which might include children's perspectives (participation and governance approaches). The results revealed organizational differences and more active consideration of children as urban open space users in Sweden than in Denmark. A general ambition to increase children's participation was reported, but also associated challenges, including budget limitations and lack of knowledge among managers. More ambitious and child-centered urban open space management units work collaboratively and broadly, through governance processes. This includes going beyond conventional structures and perceptions of what are “places for children” and consider all levels of strategic management (policy, tactical, and operational) in developing child-friendly environments within urban open spaces. The large differences between various management units indicates the importance of individual employees' knowledge and dedication, and the value of exchanging knowledge and experiences.

Introduction

Background

Access by children to urban open spaces, especially the green, brings a large number of advantages, including better physical health and lower risk of e.g., overweight (Bell et al., 2008) and mental illness later in life (Engemann et al., 2019). Through play outdoors, children develop cognitive and physical abilities, and learn how to manage risk situations (Sandseter, 2014). The importance of safeguarding children's access to green environments is therefore highlighted by several international organizations (World Health Organization, 2017; United Nations, 2019). Processes such as green space planning, design, and management have also been highlighted, as these shape the properties and characteristics of open spaces, and thereby their values for children (Jansson et al., 2016). Children generally appreciate having access to well-kept places, perceived as cared for and safe, and unmanaged places, with freedom in finding own uses (Elsley, 2004; Jansson et al., 2016). This shows the importance of providing variety in local urban open spaces for children's uses and preferences.

There is also a need to apply governance perspectives in order to include the uses and preferences of children as a user group within urban open space management, since their interests otherwise tend to be excluded (Elsley, 2004; Fors et al., 2020). Adults can play an important role in promoting children's interests through a child-centered perspective, which may include adults' views on children's perspectives, i.e., a child perspective, but also might encourage children to participate and thereby include children's perspectives (Björklid and Nordström, 2012; Jansson, 2015). Children's perspectives on green spaces generally differ from adults', focusing more on function and active use and less on e.g., order (Francis, 1988; Björklid and Nordström, 2012) and studies have shown that managers only partly understand children's use and perspectives (Bell et al., 2003; Jansson, 2015). Children's participation can be of various types, where direct processes on an everyday level are valuable (Clark and Percy-Smith, 2006; Fors et al., 2020) as sustained inclusion of children also lead to more inclusive spaces (Derr and Tarantini, 2016). Furthermore, urban open space management may need to consider more spaces than those designed specifically for children's play, since children generally prefer using a variety of spaces (Elsley, 2004; Jansson et al., 2016). Considering the potential value of orienting work in urban open space management increasingly toward children as a user group, it is of interest to study how managers relate to children as users.

Urban open space management (often denoted as park management) can broadly be described as a “strategic, inclusive and long-sighted approach of continued re-planning, re-design, re-construction, and maintenance” (Jansson and Randrup, 2020, p. 12). Randrup and Persson (2009) introduced the strategic park management model to evaluate urban open space management as relating to spaces, users, and managers, the latter on three levels (policy, tactical, and operational). The policy level of management concerns the political and strategic direction, including the formulation of long-term visions and goals. On the tactical level, plans and guidelines are produced, including e.g., green structure plans and playground plans. It is often on the tactical level that formal participatory approaches are initiated. The operational level is more concrete, considering maintenance and upkeep of open spaces (Randrup and Persson, 2009; Randrup and Jansson, 2020). The three levels are not totally separable, as they influence each other and overlap and can also be influenced by a large number of actors in various types of governance arrangements (Jansson et al., 2019). Thus, issues in urban open space management are often both sectoral (relating to management) and cross-sectoral (relating to the larger organization) (Randrup and Jansson, 2020).

Individual urban open space managers can play an important role in supporting governance processes and user-oriented urban open space management, including as facilitators of public involvement (Molin and Konijnendijk van den Bosch, 2014; Fors et al., 2018; Fongar et al., 2019). This role can be challenging and is perceived as being beyond the competence of several managers (Molin and Konijnendijk van den Bosch, 2014), while some find themselves able for the task (Fors et al., 2018). One way of supporting various types of participation is through “mosaic governance” (Buijs et al., 2016), stimulating several governance approaches where governmental organizations can coordinate citizen initiatives (Fors et al., 2018) so that e.g., local anchoring meets common goals such as social and ecological sustainability (Buijs et al., 2016). This study examined the perspectives of local government employees responsible for urban open space management in Swedish and Danish local governments and how they approach children as users, with the aim of improving understanding about the role of organizations and individuals in user-oriented and child-centered management work.

User-Oriented Urban Open Space Management in Sweden and Denmark

Sweden and Denmark have similar social and societal conditions, but also differences in access and in the character of urban open space and its management. During the post-war period, both countries were strongly characterized by state government, as welfare states, lately moving in a neoliberal direction (Busck et al., 2008). They have differing national and sub-national legislation and organizational structures affecting planning and management, but both are affected by the framework established by the European Union (EU) (Busck et al., 2008). The socioeconomic situation is similar in the two countries, as reflected in high quality of life (Eurostat, 2014). Denmark has a smaller land area, is more densely populated and has more urban land and farmland, while Sweden has greater areas of forest and nature (Busck et al., 2008). However, compared with other European countries, both countries have much green space and similar legislation giving people access to nature, high accessibility to preschools with cultural values of outdoor play, and play in nature is overall valued and provided (Sandseter, 2014).

Urban open space management in both countries is directed mainly toward maintenance and the operational level, with limited focus on more strategic and tactical measures (Randrup and Persson, 2009; Randrup et al., 2017). The majority of both Danish and Swedish local governments (93 and 60%, respectively) focus on control, whereas few (~30%) work with planning of green space management (Randrup and Persson, 2009). This might be caused by the growing distance between management units and politicians (Randrup and Persson, 2009). Both Swedish and Danish local governments generally use full or partial outsourcing (Randrup and Persson, 2009; Randrup et al., 2017), but Danish urban open space management units tend to use private contractors to a lesser extent than Swedish (Lindholst et al., 2020). In Denmark, user-oriented processes and participation are commonly issues at the policy or tactical management levels, or for urban planning units, and just 4% of the otherwise common voluntary work affects nature and environment (Molin and Konijnendijk van den Bosch, 2014). In Sweden, there are no indications of management units wanting to transfer maintenance to a volunteer routine (Randrup et al., 2017). A 2009 study showed that Danish local governments had the highest financial budgets for urban open space management among the Nordic countries, on average 41% above the Swedish (Randrup and Persson, 2009). However, it is in general difficult to estimate green space management budgets due to internal separation of tasks and responsibilities across departments, sections, and even units (Randrup et al., 2017, 2020).

While management of urban open space and work by urban open space managers have been found to have strong effects on the qualities, uses, and possibilities for children and young people (Bell et al., 2003; Elsley, 2004; Jansson, 2015; Jansson et al., 2016), little is known on how urban open space management units can be child-centered (Jansson et al., 2016) and include children in governance processes (Fors et al., 2020). There is also a lack of overall information on what is already being done today by local governments, although such information can be valuable in developing more user-oriented urban open space management approaches.

Aims and Research Questions

The present survey was conducted with the aim of obtaining an overview of how local government urban open space management in municipalities in Sweden and Denmark is oriented to children as a user group, in order to identify experiences, differences, and possible improvements. The following research questions guided the work:

1. How do Swedish and Danish local government urban open space management units, through their organization and activities, work for users in general and children in particular?

2. How do Swedish and Danish local government urban open space management units approach children's participation?

3. Which types of environments do urban open space managers consider relevant to adapt for children as users?

4. What challenges can be identified in urban open space governance and management approaches to children?

Materials and Methods

Selection of Cases

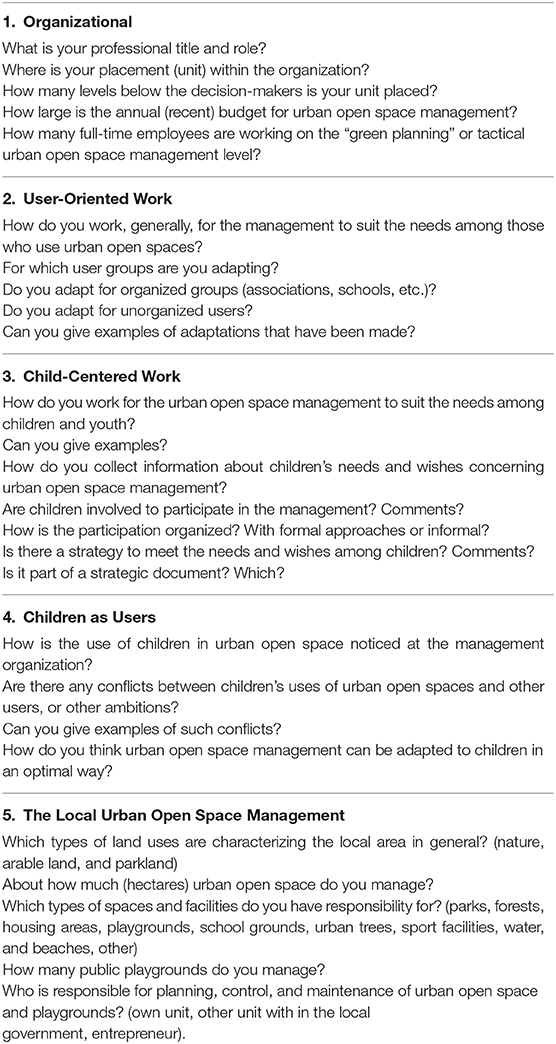

A questionnaire-based telephone survey was conducted with local government urban open space managers in municipalities in Sweden and Denmark. We divided both Denmark and Sweden into geographical areas, in order to secure a national representation. In Denmark we divided the country into two areas; Eastern (capital area and Själland) and Western Denmark (Nordjylland, Midtjylland, and Syddanmark), while Sweden was divided into three geographical areas: Northern (Norrland), Central (Svealand), and Southern Sweden (Götaland) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Sweden and Denmark showing distribution of the municipalities where local governments were surveyed in different geographical areas.

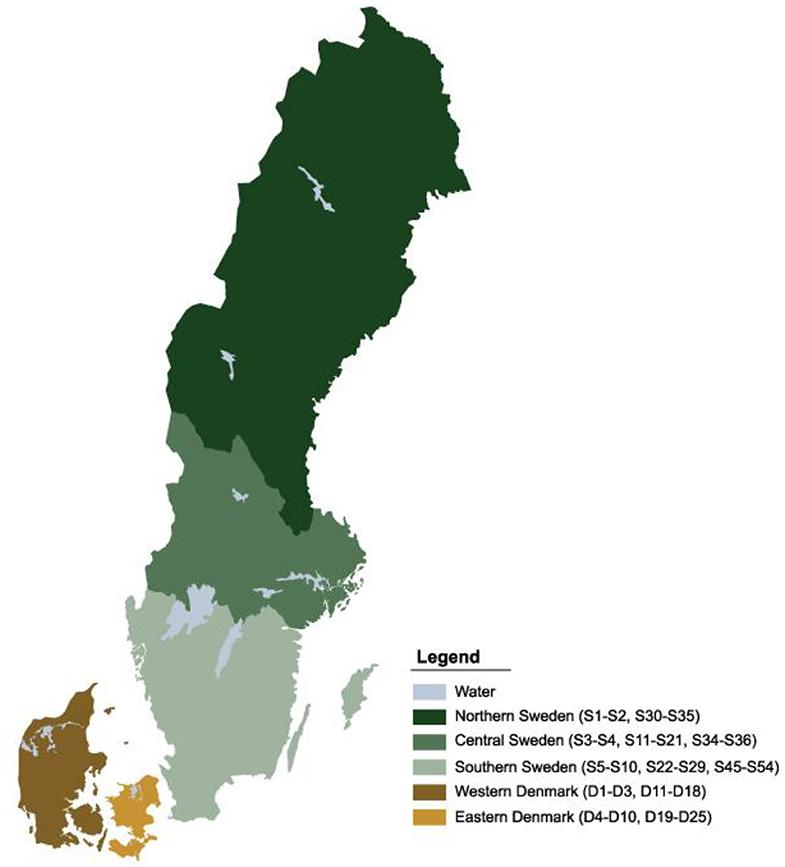

The local governments/municipalities included were purposefully selected with the aim of achieving diversity in geographical placement (Denmark = D, Sweden = S) and size (large, middle-sized, small), where large municipalites have >60,000 inhabitants, middle-sized have 20,000–60,000 inhabitants, and small have <20,000 inhabitants (Table 1). The respondents represented 54 Swedish local governments (coded S1–S54) (around 20% of a total of 290) and 25 Danish local governments (coded D1–D25) (over 25% of a total of 98), and were often the local government employees responsible for urban open space management, occasionally involving one more person.

Table 1. Numbers and codes of local governments/municipalities in different size classes surveyed in different areas of Denmark (D1–D25) and Sweden (S1–S54).

Procedure

First the questionnaire was tested on 10 Swedish local governments in 2015, by the main researcher. That design was approved and after slight adjustments to only the order of questions, it was used also for the remaining interviews, conducted in 2017 by two additional researchers, one Swedish-speaking and one Danish-speaking, following instructions from the main researcher.

On phoning a local government, a request was made to speak to the person responsible for park management. A time was then booked for a telephone interview with this person, or the interview was conducted directly, lasting 15–45 min. The questionnaire (see Table 2) included basic questions about the local government organization, its park management department/unit, and the interviewees' roles and responsibilities. More specific questions were related to user-oriented management, first in general and then for children in particular. Closed questions (e.g., number of full-time employees) were interspersed with open questions (e.g., examples of adaptations made) that often yielded extensive responses. The responses were noted, using a mid-level of transcription detail and compiled in a digital form. Besides the responses to the actual questions posed, the interviewers also noted their general impression of the interview regarding: (1) whether there was interest in children's participation or not; and (2) whether the work with children included several types of open spaces, or was mainly limited to playgrounds. The age group of “children” was not defined during the interviews.

The analysis was conducted with each of the four research questions in focus and it was mainly qualitative, using the digital form to sort and thematize the data, but some answers to the closed questions were also analyzed quantitatively. In some cases we have used themes from the qualitative answers to the open questions in order to set estimates. However, the quantitative results must be considered general, rather than statistically proven values.

Results

Work With Children and Other Users

The few individuals that work with tactical-level urban open space management in local governments in Sweden and Denmark appeared to be of major importance for the work of adapting governance approaches to users, in particular to children. The local governments had a median of two and an average of 3.6 full-time employees, and 90% had <5 full-time employees. The number of employees was slightly higher in Denmark than in Sweden. Use of a child perspective, its recognition on policy levels, and allocation of resources to this within the local government organization appeared to depend greatly on these few individuals in tactical level urban open space management and their knowledge and engagement. The interviewee representing S5 reported that one employee, the city gardener, is responsible for implementing several central actions, including staffed playgrounds. The interviewee representing S8 reported that a city gardener has worked much with adaptation to children but, since that person was on sick leave, the interviewee had difficulties describing the work. In S37, the interviewee was employed half-time by the local government housing company and described this as a major advantage in coordinating the work. The interviewees in Danish local governments D9 and D25 reported that they were responsible for maintenance and upkeep, and viewed themselves as personally responsible for large parts of the work. These responses indicate that in both counties, the work toward different user groups, specifically children, is dependent on a few individuals and their personal engagement.

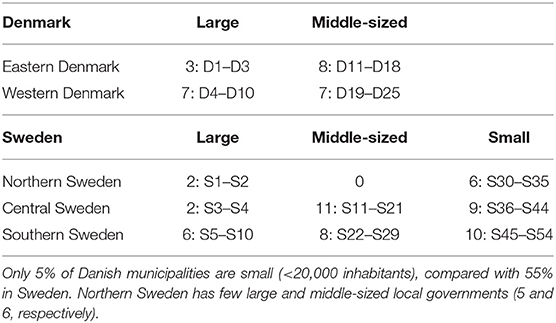

Work with children differed between Swedish and Danish park management organizations (Figure 2). When asked which specific user groups park management is tailored toward, more than half of the Swedish local governments mentioned children directly and some others mentioned groups that indirectly include children, such as families. In contrast, none of the Danish local governments mentioned children as a group, but around a quarter of them more generally mentioned families or young people. Around 45% of the Danish interviewees stated that they tailor management to “everyone,” “no-one specific,” or “the citizens,” while the Swedish interviewees mentioned several groups besides children, including young people (around 20%) and people with disabilities (around 60%). The elderly or retired were mentioned in both Sweden (about 35% of interviewees) and Denmark (20%).

Figure 2. Proportion (%) of interviewees representing Swedish and Danish local government urban open space management units who mentioned children as a user group considered in their work (yes/no) or doing it indirectly. Sweden: n = 54, Denmark: n = 25.

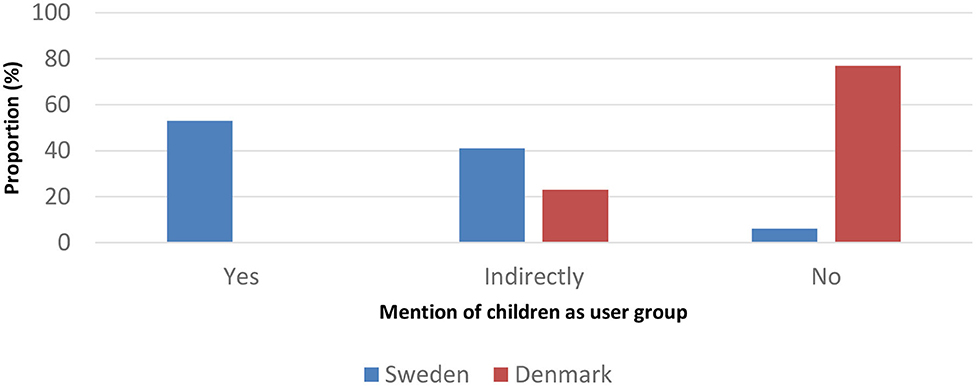

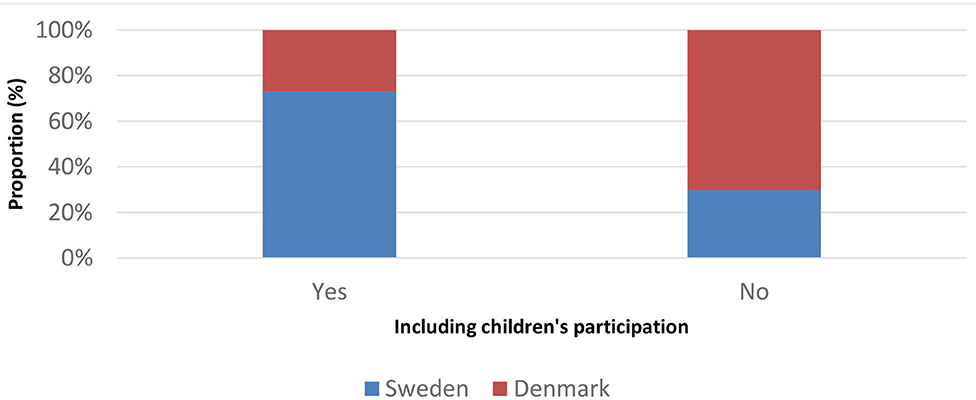

There were also large differences regarding whether children's perspectives were included or not. Sixty eight % of Swedish and 25% of Danish interviewees reported that their unit works with children's participation (Figure 3). Danish urban open space management units generally do not collect information or requests from local children as users, but might get them through other local government units. In Sweden, park managers reported that they often collaborate with schools and preschools, either directly with the children or through the teaching staff, to learn about children's preferences. However, there are also large differences within Sweden. S6 reported that a child perspective is present in all its work, with full-time teaching staff used to implement the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and checklists securing a child perspective in the outdoor environment. In comparison, the representative of the geographically close (but smaller) S23 claimed that the outdoor environment is already optimally adapted, since the playgrounds are much used, and that suggestions made concerning children may be met, although not following any specific strategy. This was similar to the indirect approach found in many Danish local governments, with e.g., D15 having no explicit way of including children's perspectives, but trying to follow incoming calls about issues (often small and practical) which might be relevant also for children.

Figure 3. Proportion (%) of interviewees representing Swedish and Danish local government urban open space management units stating that their unit works with children's participation. Sweden: n = 54, Denmark: n = 25.

Organizing Urban Open Space Management for Specific User Groups

Individual local governments appeared to be organizing their urban open space management work differently and to some extent there were also national differences. It was primarily in the larger municipalities in both Sweden and Denmark that local governments reported to have active user-oriented approaches, mainly through informal projects with the focus on specific users, including children. The local government urban open space management units in both Sweden and Denmark are most commonly (around 60%) placed two administrative levels below the political decision makers, but while in Sweden the second most common alternative is three levels below, it is just one level below in Denmark. Despite this indication of a larger distance from decision makers in Sweden, there is more work on policy and tactical levels in Sweden than in Denmark, where urban open space management is instead more often considered primarily operational. Swedish interviewees reported that their urban open space management unit also commonly deals with the planning, supervision/control, and maintenance of urban open space management, which was not the case in Denmark, but outsourcing of operational tasks such as maintenance to contractors was still more common in Sweden.

Questions concerning children's outdoor environments received more focus overall in the Swedish urban open space management units than in the Danish, where the interviewees more often than in Sweden referred to work for children, e.g., in developing strategic documents, holding dialog, and even in working with playgrounds, taking place in other local government units. This indicates that the Danish urban open space management units are more operational than tactical, and that they have limited connection to children. The results were even clearer concerning playgrounds, which in Denmark were often the responsibility of units dedicated to the operational level.

Overall, strategic user-oriented management appeared to be more common in Swedish than in Danish local governments, despite much variation within Sweden. Interviewees in Danish (70%) and Swedish (64%) local governments reported having strategic documents relating to children, young people, and park management. However, in Denmark these documents are often produced outside the urban open space management unit, such as in the planning unit. Since strategy, user participation, etc. were seen as better suited to other units than urban open space management, the links between the three levels of strategic management (policy, tactical, and operational) were generally weak. The interviewees in D2 and D23 reported that the planning unit conducts work with children's participation, which they did not consider of interest for their department working only with maintenance. This can be compared with Swedish local government S12, where the playground plan has strategies for everything from physical activity and experiences to practical issues around planning for maintenance and choices of materials. S12 also conducts active work on adapting green space provision to children and involving them in planning and management processes, e.g., in spring cleaning events.

The urban open space management units that appeared to succeed best in organizing user-oriented management for children were reported to employ a combination of participatory processes that included children's perspectives and other child-centered measures by several actors and on all levels: policy, tactical, and operational. The urban open space management units that work child-centered also tend to have individuals taking such initiatives employed in the unit, in other units (planning, culture, leisure, and education), or in associations outside local government influencing the urban open space management unit. The work is not always the result of larger strategic or visionary approaches, but sometimes builds on more informal initiatives. Furthermore, these urban open space management units tend to be found in larger municipalities, as responses showed that 70–80% of the large and middle-sized Swedish municipalities surveyed, but only 45% of the small, have local governments that involve children and that the few cases of involvement of children in Denmark were all in large municipalities.

Children's Participation in Urban Open Space Management

The results showed that specific initiatives are required to access children's perspectives. The most common ways to communicate between urban open space management and users (citizen surveys and proposals via website or social media) rarely provide a direct link between the urban open space management and children. However, several local governments work in projects where various actors can have temporary collaborations to make the management more user-oriented and child-centered. In Swedish S37, the requests of associations concerning outdoor environments can be met through “extra money” for special measures, like providing a BMX track for young people in a sports club. S22 supports EU projects that the citizens themselves manage and partly finance through grant applications. In S51, preschools and schools have worked with gardening through the school leader, indirectly including the park management. In Denmark, D5 has worked widely with a pilot project studying forms of participation in urban open space management. In D7, a collaboration between planning, management, teaching staff, and trainee teachers has involved children in management work.

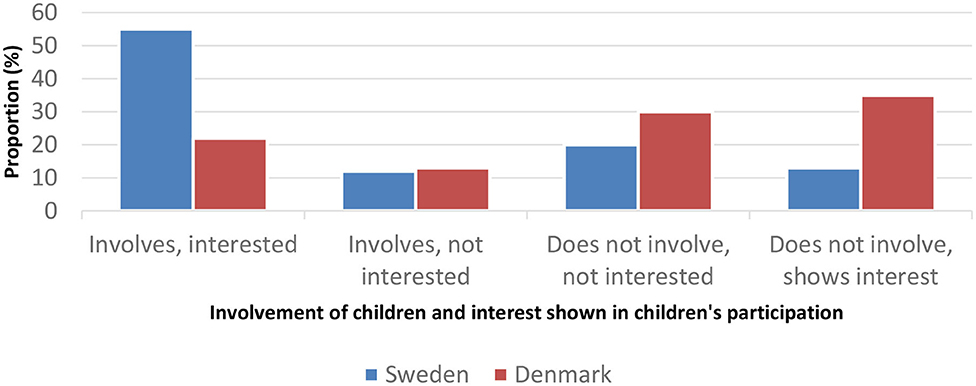

In both the Swedish and Danish local governments surveyed, children's participation in urban open space management was generally considered an ideal. However, such participatory approaches were much more common in the Swedish local governments (Figure 4), where children were reported to be involved e.g., through adapted consultations, walks, “test play”, and workshops. The most common response from interviewees in Denmark was that the urban open space management unit does not work with children's participation, but that other units sometimes do so. However, around 20% of the Danish interviewees wanted to initiate participatory approaches for children. More surprisingly, around 12% of the interviewees in both countries which claimed to work with children's participation, showed little interest in it. Problems described were mainly that children do not perceive limits and frames to their wishes and expectations, posing a risk of ending up with requests that cannot be met.

Figure 4. Proportion (%) of Swedish and Danish local government urban open space management units reported to be involved and/or interested in including children's participation in their work.

There were also differences between the countries concerning how much children are involved directly. Swedish and Danish local governments were reported to collaborate with preschools and schools, but the Danish local governments collaborated mostly with teaching staff, while the Swedish also collaborated with children. In Swedish S3, the interviewee emphasized the importance of direct communication with children, without adult influence. In S28, optimal dialogue with children was described as involving adults as little as possible. The interviewee in Danish D25 claimed that adults “don't keep up,” and that children must be asked directly about their preferences. In both D5 and D24, differences in preferences and approaches between children and parents and other adults were described as important, as e.g., adults' focus on safety might not fit children's creative ideas.

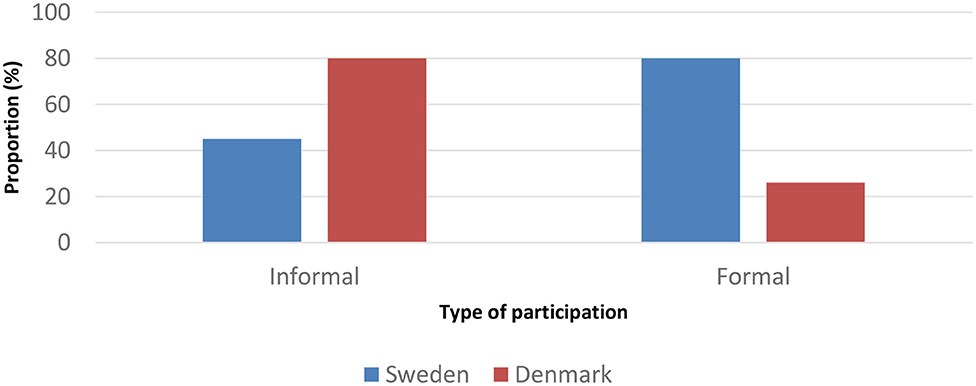

A vast majority of the interviewees cited examples of some sort of children's participation performed by their unit, even interviewees who claimed that their unit conducts no such work. Children's participation appeared to be more common and also more formally organized in Sweden than in Denmark (Figure 5). Although more common in larger municipalities in both countries, various types of children's participation occurred in various municipality sizes. Some representatives of urban open space management units gave examples of working with both formal and informal participation, others with only one type, and some none at all. Swedish S49 is an example of how formal and informal participation approaches are combined. There, the urban open space management unit was reported to collaborate with schools to engage children in the management of local outdoor environments, e.g., in a yearly cleaning day, a theme day about wood production, and a “school forest,” where children often take own initiatives for maintenance. This can be compared with Danish D4, where the interviewee mentioned a clear strategy document aiming to strengthen participation by children and young people that partly applies to outdoor environments, but which has not resulted in any actual participation as yet. Interviewees representing a number of Danish urban open space management units, such as D1, D3, D17, and D20, characterized their participatory approach as “ad-hoc,” often not including participation but rather adaptation to children by fixing concrete problems, often after complaints or suggestions from parents or teachers.

Figure 5. Proportion (%) of Swedish and Danish local government urban open space management units reported to have means of enabling children's participation in informal and formal ways.

In several municipalities in both countries, children's participation in urban open space management was described mostly on the operational level. In Sweden, this often concerned cleaning through the national project “Håll Sverige Rent” (Keep Sweden Clean) or similar local projects on picking litter or cleaning in collaboration with children and young people, preschools, or schools. In S29, a creative task for children to both educate and collect ideas for cleaning has been launched. Examples were also mentioned of children spontaneously showing an interest in maintenance and asking to help operational staff (e.g., with raking leaves). Operational activities like cleaning appeared to be the focus for children's participation in Sweden, both as formally organized and more informal participation.

Types of Places Considered for Children's Use

Despite much focus on providing playgrounds, the majority of the local government representatives in both countries also mentioned the importance of working with other types of spaces. The Danish local governments surveyed were found to have on average 23 playgrounds (maximum 100), while Swedish had on average 41 playgrounds (maximum 292). Most of the Danish interviewees talked primarily about playgrounds, e.g., having strategies for playgrounds or assessing children's use of green spaces through wear and tear on play equipment. Many (60% of Swedish and 70% of Danish interviewees) also referred to work with other green spaces related to children as users, with examples often given by local governments in middle-sized or small municipalities. The interviewee in Danish D25 said that requests from children and young people had increased lately, including for role play or biking events. In D19, the primary local outdoor environment for children and young people was described as a green belt surrounding the built environment, providing environments often used for teaching, which gives them an early relation to green space management. In Sweden, the work on including children was reported to often be centered on playgrounds and school grounds, but there were also ideas on widening the child perspective from there, sometimes literally. In S46, a project has been initiated to make the road to school more interesting, to encourage children's use of outdoor environments. In S13, a school grounds project has included surrounding spaces, while interviewees from S25, S29, S30, S37, and S45 all mentioned “school forests” as an important part of their urban open space management focusing on children and families. In S19, the interviewee said that existing play environments are being improved by ensuring that they are connected to a “play path.”

Local governments with more and better experiences of directing their work more specifically toward children, and larger financial resources, were reported to more often include other parts of the urban environment than e.g., playgrounds, in their work for children. These examples were mostly found in Swedish local governments, such as S6 emphasizing handling traffic issues based on children's needs and preferences, a general increase in parkland, and spreading out the places specifically planned and managed with children in mind to provide proximity—not necessarily full-scale playgrounds but rather other interesting places that children can discover on their own.

The Challenges of Working With Children as a User Group

Up to 40% of the interviewees in both countries referred to finances as a problem or limitation in orienting their work more toward children. Budgets varied widely across the local governments in various categories, although the highest budgets were found in large municipalities and the lowest in small. The interviewees in Swedish S11 and S43 described not being able to afford to do more than they are already doing. Finances were seen as restricting possibilities even where budgets were comparably high, like in S49, where the interviewee listed opportunities to do much more with more money. In Danish D21, the economic frames were described as determining how the work for/with children can actually be done, despite children's needs always being included in planning and management issues. S32 reported the lowest budget of all local governments surveyed, and described building playgrounds as being too expensive due to safety regulations. The interviewees in S2 and S39 reported wishes and ideas for children's participation, but no financial support. In Danish D16, work directed toward children was described as always requiring extra funding with e.g., expensive play equipment making the costs untenable, including in view of parity between user groups. In D7, the interviewee reported trying to implement a child perspective through simple measures, since larger ideas were directly “killed” by budget limitations.

Lack of experiences, knowledge, and strategies also appeared to limit children's participation. Representatives of several urban open space management units found it difficult to picture how to adapt to children, irrespective of budget level. In Swedish S11, the interviewee did not know how to work optimally with children, but thought dialog “could be a good measure.” Almost a quarter of the Danish local governments surveyed (e.g., D3, D16, and D21), along with a few Swedish, found it very difficult to answer the question about optimal urban open space management for children. D11 expressed a wish to orient work toward children, but found challenges in having several age groups share the same spaces while meeting the wishes of small children. S14 wanted to access the views of users, including children, but lacked a procedure for this. In S34, the lack of an explicit strategy to steer the work was reported to be limiting, while in D8 the interviewee wanted to make an analysis of availability before setting the needs for further work.

For some of the urban open space management units, mainly larger ones, the survey responses indicated that knowledge and creativity might be ways of overcoming challenges such as limiting budgets. Danish D5 has implemented citizen budgets, giving people money through projects to develop local government resources. Several Swedish interviewees raised self-management as a solution. Some also mentioned small maintenance measures giving large effects and thereby being cost-effective. In S7, this has included provision of flower meadows, while in S3 it has involved painting rocks or placing sculptures to interest children. S29 pointed out that accessibility for strollers and wheelchairs could be improved through small maintenance measures, such as removing stones and roots.

Conflicts concerning children's uses of outdoor environments in relation to other user groups were described rather similarly in the two countries. Initially, over 60% of the interviewees claimed that there were no such conflicts, but several also gave examples of conflicts. D3 mentioned conflicts between older and younger children with different needs and preferences. Others mentioned balancing conflicts of interest between children seeking challenges and parents mainly concerned with safety. Some interviewees, mainly in Sweden, described how the elderly look for well-kept areas, while children like the unkempt, or even “messy.” In S3, there is therefore an endeavor to provide unkempt surfaces in urban areas, along with measures to improve children's independent mobility. Despite this, younger children were not considered a troublesome user group for urban open space management, while youth were seen as more problematic. That perspective was voiced in both countries, but in Denmark in particular. Conflicts were often about youth disturbing other users with e.g., high sound volume. In Danish D18, the interviewee described youth as often causing problems and being difficult to interact with.

Another conflict concerned the increased competition for urban open space, particularly the effect of densification, mainly mentioned by Swedish interviewees. S21 experienced conflicts between different users growing more common when striving for multifunction in urban open spaces. The interviewee in S5 had started to notice consequences of densification, as school grounds have shrunk and the competition for other surfaces has increased, resulting in less access and also lower quality of vegetation through wear and tear. Representatives of several urban open space management units, all in “small” municipalities such as S36 and S48, reported that they have no conflicts because of the spaces being large enough to avoid this. S41 referred to the many private gardens as protecting the parks from being worn out by children. The interviewee in S45 described the importance of counteracting densification and in S47 suggested that densification may cause problems such as too small play spaces, where children and their perspectives must then be prioritized. The Danish interviewees touched upon the question of densification more indirectly than the Swedish, by indicating that different interests might compete in areas which many share, particularly concerning young people. In D4 and D8, mountain biking was mentioned as specifically difficult to handle, requiring space and disturbing other users.

Discussion

Child-Centered Urban Open Space Management in Denmark, Children's Perspectives in Sweden

This overview of local government urban open space management work for children in Sweden and Denmark revealed differences between the countries, in particular that Swedish local governments are working more actively than Danish local governments to adapt management to children. The Swedish responses demonstrated adults advocating children's interests through a child-centered perspective and also inclusion of children's own perspectives through participation and governance processes. The Danish responses indicated work mainly with a child-centered perspective, or no active work concerning children as a user group in urban open space. Similarities included a general ideal to increase children's participation, but also associated challenges, including budget limitations and lack of specific knowledge among managers.

While the Swedish local governments appeared to direct their work toward children and other specific user groups, the Danish interviewees tended to view urban open space management work as being for all users. While it is not clear which approach that is most successful, Cele (2015) showed that working for “all” runs the risk that groups like children, with special needs and requests, will not be visible. In order to adapt urban open space management for children, so that they can use urban open spaces in their own right (Elsley, 2004), special measures such as e.g., the mosaic governance approach proposed by Buijs et al. (2016) might therefore be needed, going beyond the most common processes and ways of communicating with users, as well as directing governance models for specific geographical as well as user-oriented means.

Strategic Work and Organizational Factors

In the urban open space management units which work in a user-oriented, active way and include children's participation through e.g., dialog or operational maintenance work, the work tended to be driven by one or a few highly committed local government employees. This demonstrates the crucial role that individuals play in determining whether work is adapted to children or not, and also demonstrates the vulnerability of governance approaches depending on a few dedicated employees. Previous studies have shown that urban open space managers can be facilitators of user-oriented management and participation (Molin and Konijnendijk van den Bosch, 2014; Fors et al., 2018), but that a large knowledge base is needed (Fors et al., 2020), along with methods to understand children's embodied experience even when not expressed verbally (Björklid and Nordström, 2007). However, the smallest municipalities surveyed rarely had children participating, which might indicate a need for a certain number of employees and some level of economic and organizational responses in order to work inclusively with children.

The results show a need for a wide, collaborative approach in order to achieve successful, user-oriented urban open space management for children, where some local governments had developed own such approaches. Woolley (2017) emphasized the need for cooperation in a wide sense in the work on children's environments. This could include various actors, within and outside local government organizations, and several participatory processes, formal and informal. This type of mosaic governance means that various forms of initiatives, both top-down and bottom-up, can be supported by urban open space managers acting as facilitators of user participation (Buijs et al., 2016).

Strategic work did not always seem to lead to changes on the operational level or be well-connected with it. Particularly in Denmark, but also to some extent in Sweden, urban open space management units were reported to be mainly operational, which is in line with results from previous studies (Randrup and Persson, 2009). This leads to e.g., children's participation occurring mostly in an informal and “ad-hoc” way, rather than being based on user-oriented governance strategies. Policy frameworks can directly affect the environments children use in their daily lives, but whether the original intentions are fulfilled depends on funding, delivery organization, and the commitment of specific individuals (Woolley, 2017). This shows risks associated with weak connections between strategic levels that go both ways, e.g., policy may be formulated based on abstract perceptions of children's opinions and needs (Elsley, 2004), or approaches to children may lack policy support.

Links between the three strategic levels of urban open space management appear to be of crucial importance. Experiences and knowledge of children as users can be collected on the operational level, where much of the participation found in this study occurred and where children often like to contribute (Jansson, 2015), but this needs to influence the tactical and policy levels. Work on the operational level can also be supported by strategies set on the policy and tactical levels to include children as a user group. Organizational factors also appear to influence the possibilities for links between the strategic levels, as many of the Danish local governments surveyed had mainly operational urban open space management units that were separated from strategic work and documents or participatory processes in other units. In the Swedish urban open space management units, problems in achieving these links might instead be a result of much of the work on the operational level being outsourced to contractors.

Overcoming the Main Challenges

Younger children appears to be a group that is not in itself considered problematic as urban open space users, and their use and even wear and tear appears widely accepted among the managers. The challenges to overcome were rather connected to other aspects than the use, such as economic aspects and uncertainly around participatory approaches. However, similar to previous studies (Bell et al., 2003), older children or youth are sometimes seen as involved in conflicts which the managers find difficult to solve.

Economic restraints were described as a major limitation in most of the urban open space management units surveyed, with expensive play equipment reported to use up much of the budget and units wanting to do more for children, but not being able to afford it. Some interviewees reported having partly overcome these problems with creative solutions and high knowledge levels, as e.g., self-management approaches can increase local anchoring and limit costs (Molin and Konijnendijk van den Bosch, 2014; Fors et al., 2020). There are examples of units working with small measures in the physical environment, aiming to give large effects for certain user groups. This can mean including a child perspective on more than traditional playgrounds, which might also increase child-friendliness in urban environments in times when children's access and mobility are often decreasing (Hand et al., 2018) and areas for them are shrinking (Kylin and Bodelius, 2015). Creative solutions require knowledge about children as urban open space users, and might lead to greater budgets if they demonstrate the value of user-oriented urban open space management. To increase knowledge on children's perspectives among local government employees in urban open space management units can therefore be considered key to using available resources well.

Among the local governments surveyed, children's direct participation in urban open space management was considered a challenge by many. Some avoided it totally while some preferred dialog with adults instead. There were fears of children's ideas being too unrealistic, risking disappointment. This might indicate that well-functioning approaches to children's participation are lacking. Adults' responses have previously been found to be frustrating to participating young people, and there is a need to develop a good balance with policy interests and suitable methods (Derr et al., 2013). However, there are also claims that children are more realistically situated in their environments if they do have good access to nearby green environments (Björklid and Nordström, 2007). This shows the importance of child-centered urban open space management in a very broad sense, ensuring access as a basis for children's participation.

Methods Discussion

This survey covered 20–25% of Swedish and Danish local governments and their key personnel in urban open space management, and the approach allowed both qualitative and quantitative data collection. While there was an aim of keeping the interviews rather open, more definitions (e.g., of the ages aimed for) could have increased the consistency, as questions might have been interpreted differently by different interviewees. Other methodological weaknesses include use of three different interviewers over a period of two years, risking differences in approach. Additionally, some interviewees were unable to answer all questions, which affected the data collected.

Conclusions

This survey revealed differences between Danish and Swedish local governments in approaches to children as users of urban open space. Swedish urban open space management units have more governance perspectives and work more with children and other groups specifically, and with children's participation more directly, while the work in Danish urban open space management units is more indirect, such as building on information collected by other parts of the local government organization. This appears to, at least partly, be a result of organizational differences. In Sweden, there is more collaboration between the strategic levels (policy, tactical, and operational), while Danish urban open space management units are often more operational and refer user-oriented work to other parts of the organization.

The survey also revealed large differences between local governments and municipalities within each country, depending on organization, size, budgets, densification of urban open space, and other factors, but also on the level of individual engagement among local government employees. The local governments with the highest ambitions in optimizing work toward children have more mosaic governance approaches as they implement a child perspective over the entire urban open space and not just “places for children,” use several types of processes in management and planning, and combine formal and informal approaches for children's participation. This requires knowledge among individuals in order to find ways of overcoming limited budgets. Knowledge exchange within and between urban open space managers in various local governments can be a way of both limiting the vulnerability of few people involved and of increasing learning from best practice cases.

This study revealed knowledge gaps concerning user-oriented urban open space management for children to be addressed in future research and in practice. Some best practices among urban open space management units were identified, which can inspire more and better work on inclusion of children's perspectives. There is also a need to improve the links between various organizational units and levels affecting urban open space management, in order to increase collaboration between the units, strengthen strategic and tactical perspectives, and encounter children and young people on the operational level, where urban open space managers can act as facilitators of collaboration. A greater focus on governance processes and participatory methods could increase the possibilities for strategic and user-oriented management.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

This work builds on a study in all stages conducted by MJ, supported by TBR in planning, by EPS in data collection, by AZ in analysis, and by all co-authors in writing.

Funding

This work was part of research project 225-2014-1552 funded by the Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning, FORMAS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors also which to thank all the interviewees for their time and engagement in this study and Anne Qattanneq Ignatiussen for her excellent assistance.

References

Bell, J. F., Wilson, J. S., and Liu, G. C. (2008). Neighborhood greenness and 2-year changes in body mass index of children and youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 6, 547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.07.006

Bell, S., Ward Thompson, C., and Travlou, P. (2003). Contested views of freedom and control: children, teenagers and urban fringe woodlands in central Scotland. Urban For. Urban Green. 3, 87–100. doi: 10.1078/1618-8667-00026

Björklid, P., and Nordström, M. (2007). Environmental child-friendliness: collaboration and future research. Child. Youth Environ. 17, 388–401. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.17.4.0388

Björklid, P., and Nordström, M. (2012). Child-friendly cities—sustainable cities. Early Childhood Matt. 118, 44–47.

Buijs, A. E., Mattijsen, T. J. M., Van der Jagt, A. P. N., Ambrose-Oji, B., Andersson, E., Elands, B. H. M., et al. (2016). Active citizenship for urban green infrastructure: fostering the diversity and dynamics of citizen contributions through mosaic governance. Environ. Sustain. 22, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.002

Busck, A. G., Hidding, M. C., Kristensen, S. B. P., Persson, C., and Præstholm, S. (2008). Managing rurban landscapes in the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden: comparing planning systems and instruments in three different contexts. Danish J. Geogr. 108, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/00167223.2008.10649584

Cele, S. (2015). Childhood in a neoliberal utopia: planning rhetoric and parental conceptions in contemporary stockholm. Geografiska Annaler 97, 233–247. doi: 10.1111/geob.12078

Clark, A., and Percy-Smith, B. (2006). Beyond consultation: participation practices in everyday spaces. Child. Youth Environ. 16, 1–9. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.16.2.0001

Derr, V., Chawla, L., Mintzer, M., Flanders Cushing, D., and Van Vliet, W. (2013). A city for all citizens: integrating children and youth from marginalized populations into city planning. Buildings 3, 482–505. doi: 10.3390/buildings3030482

Derr, V., and Tarantini, E. (2016). “Because we are all people”: outcomes and reflections from young people's participation in the planning and design of child-friendly public spaces. Local Environ. 21, 1534–1556. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2016.1145643

Elsley, S. (2004). Children's experiences of public space. Children Soc. 18, 155–164. doi: 10.1002/chi.822

Engemann, K., Pedersen, C. B., Arg, L., Tsirogiannis, C., Mortensen, P. B., and Svenning, J.-C. (2019). Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 11, 5188–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807504116

Eurostat (2014). GDP and Beyond: Measuring Quality of Life in the EU. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/5181290/3-19032014-CP-EN.PDF/d8224753-699c-4cd4-b278-8c2e154a42be (accessed January 14, 2020).

Fongar, C., Randrup, T. B., Wiström, B., and Solfjeld, I. (2019). Public urban green space management in norwegian municipalities: a manager's perspective on place-keeping. Urban For. Urban Green 44:126438. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126438

Fors, H., Ambrose-Oji, B., Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C., Mellqvist, H., and Jansson, M. (2020). “Participation in urban open space governance and management,” in Urban Open Space Governance and Management, eds M. Jansson, and T. B. Randrup (London and New York, NY: Routledge), 112–128. doi: 10.4324/9780429056109-9

Fors, H., Busse Nielsen, A., Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C. C., and Jansson, M. (2018). From borders to ecotones: private-public co-management of urban woodland edges bordering private housing. Urban For. Urban Green 30, 46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2017.12.018

Francis, M. (1988). Negotiating between child and adult design values. Des. Stud. 9, 67–75. doi: 10.1016/0142-694X(88)90032-4

Hand, K. L., Freeman, C., Seddon, P. J., Recio, M. R., Stein, A., and van Heezik, Y. (2018). Restricted home ranges reduce children's opportunities to connect to nature: demographic, environmental and parental influences. Landsc. Urban Plan 172, 69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.12.004

Jansson, M. (2015). Children's perspectives on playground use as a basis for children's participation in local play space management. Local Environ. 20, 165–179. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2013.857646

Jansson, M., and Randrup, T. B. (2020). “Defining urban open space governance and management,” in Urban Open Space Governance and Management, eds M. Jansson and T. B. Randrup (London and New York, NY: Routledge), 11–29. doi: 10.4324/9780429056109

Jansson, M., Sundevall, E., and Wales, M. (2016). The role of green spaces and their management in a child-friendly urban village. Urban For. Urban Green 18, 228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2016.06.014

Jansson, M., Vogel, N., Fors, H., and Randrup, T. B. (2019). The governance of landscape management: new approaches to urban open space development. Landsc. Res. 44, 952–965. doi: 10.1080/01426397.2018.1536199

Kylin, M., and Bodelius, S. (2015). A lawful space for play: conceptualizing childhood in light of local regulations. Child. Youth Environ. 25, 86–106. doi: 10.7721/chilyoutenvi.25.2.0086

Lindholst, A. C., Dempsey, N., Randrup, T. B., and Solfjeld, I. (2020). “Lessons from case studies: working with marketization,” in Marketization in Local Government. Diffusion and Evolution in Scandinavia and England, eds A. C. Lindholst and M. B. Hansen (Palgrave Macmillan), 293–311. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-32478-0_15

Molin, J. F., and Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C. C. (2014). Between big ideas and daily realities: the roles and perspectives of danish municipal green space managers on public involvement in green space maintenance. Urban For. Urban Green 13, 553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2014.03.006

Randrup, T. B., and Jansson, M. J. (2020). “Strategic management of urban open spaces,” in Urban Open Space Governance and Management, eds M. Jansson and T. B. Randrup (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 190–203. doi: 10.4324/9780429056109-14

Randrup, T. B., Lindholst, A. C., and Dempsey, N. (2020). “Managing the maintenance of urban open spaces,” in Urban Open Space Governance and Management, eds M. Jansson and T. B. Randrup (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 150–167. doi: 10.4324/9780429056109-12

Randrup, T. B., Östberg, J., and Wiström, B. (2017). Swedish green space management—the managers perspective. Urban For. Urban Green 28, 103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2017.10.001

Randrup, T. B., and Persson, B. (2009). Public green spaces in the nordic countries: development of a new strategic management regime. Urban For. Urban Green 8, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2008.08.004

Sandseter, E. B. H. (2014). “Early years outdoor play in scandinavia,” in Exploring Outdoor Play in the Early Years, eds T. Maynard and J. Waters (Maidenhead: Open University Press), 114–126.

United Nations. (2019). Sustainable Development Goal 11: Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable. Available online at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg11 (accessed January 14, 2020).

Woolley, H. (2017). “Every child matters: policies and politics that influence children's experience of outdoor environments in England,” in Designing Cities with Children and Young People: Beyond Playgrounds and Skate Parks, eds K. Bishop and L. Corkery (New York, NY: Routledge), 137–149. doi: 10.4324/9781315710044-10

World Health Organization. (2017). Urban Green Space Interventions and Health: A review of impacts and effectiveness. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Available online at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urban-health/publications/2017/urban-green-space-interventions-and-health-a-review-of-impacts-and-effectiveness.-full-report-2017 (accessed January 14, 2020).

Keywords: child perspective, children's participation, green space governance, mosaic governance, park management, urban open space management, user-oriented management

Citation: Jansson M, Zalar A, Sundevall EP and Randrup TB (2020) Governing for Child-Friendliness? Perspectives on Children as Users Among Swedish and Danish Urban Open Space Managers. Front. Sustain. Cities 2:565418. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2020.565418

Received: 25 May 2020; Accepted: 04 September 2020;

Published: 23 October 2020.

Edited by:

Rieke Hansen, Hochschule Geisenheim University, GermanyReviewed by:

Tao Lin, Institute of Urban Environment (CAS), ChinaMegan A. Graat, University of Western Ontario, Canada

Copyright © 2020 Jansson, Zalar, Sundevall and Randrup. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Märit Jansson, marit.jansson@slu.se

Märit Jansson

Märit Jansson Alva Zalar

Alva Zalar Elin Pritzel Sundevall1

Elin Pritzel Sundevall1  Thomas B. Randrup

Thomas B. Randrup