Protecting the Ingroup? Authoritarianism, Immigration Attitudes, and Affective Polarization

- 1Department of Psychology, Kristianstad University, Kristianstad, Sweden

- 2Department of Political Science, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

- 3Department of Government, University of Essex, Colchester, United Kingdom

What makes people affectively polarized? Affective polarization is based on the idea that partisanship can be a social identity leading to polarization in the form of intergroup distancing between the own party and the other parties. In this study, we argue that perceived threats from an outgroup can spur affective polarization. To investigate this, we use the issue of immigration, often framed as a threat by right-wing groups, to examine whether individual-level differences influence how sensititivity to the perception of immigration as a threat. One such factor is the trait right-wing authoritarianism (RWA), which is characterized by emphasis on submission to authority and upholding norms of social order. The emphasis among individuals with this trait on protecting the ingroup from threats means that negativity toward immigration is likely to extend toward political opponents, resulting in an increase in affective polarization. Thus, we hypothesize that the affective polarization is likely to increase when individuals interpret immigration as threatening, particularly for the individuals who are high in RWA aggression. We evaluate and find support for this claim using a large-scale survey performed in Sweden (N = 898). The results, showing a conditional effect of immigration attitudes on affective polarization, are consistent across three commonly used measures of affective polarization as follows: trait ratings, a social distance measure, and feeling thermometers. Overall, our results show that it is important to consider intergroup threats and intergroup differences in the context of sensitivity to such threats when explaining affective polarization.

Introduction

Why do some individuals harbor particularly strong resentments against political opponents? What makes some people biased toward other partisan groups? Several scholars have suggested that many democratic societies are experiencing an increase in so-called affective polarization (e.g., Iyengar et al., 2019). Affective polarization is based on the idea that partisanship is a social identity and entails intergroup distancing between the own party and the other parties and their supporters (e.g., Iyengar et al., 2019). Affective polarization can challenge democratic societies when partisan groups are so hostile toward and biased against opponents that political compromise becomes impossible, even leading to political violence (Kalmoe and Mason, 2022). These potentially severe consequences make it important to understand the origins of affective polarization.

The previous research has identified two main causes of affective polarization. First, several authors have shown that strengthening group identification increases affective polarization (Iyengar et al., 2012; Mason, 2015; Webster and Abramowitz, 2017; Reiljan and Ryan, 2021). Second, numerous studies show that individuals become increasingly affectively polarized as their views become more ideologically extreme (Webster and Abramowitz, 2017; Harteveld, 2021; Lelkes, 2021; Renström et al., 2021). While both identity and ideology are known to be important drivers of affective polarization, our findings suggest that the perceived threats toward the individual's ingroup can spur affective polarization (see also Rogowski and Sutherland, 2016). Since the cultural issues have been stressed as causing such identity-based conflict (Gidron et al., 2020), we, in this study, focus on the issue of immigration. In short, we argue that some individuals are more likely to perceive immigration as a threat to their ingroup, which can result in the intergroup distancing at the core of affective polarization.

To make this argument, we draw on intergroup threat theory (Stephan et al., 2009, 2015), which suggests that intergroup distancing results from the perception of intergroup threats—that is, the perception that one group can threaten the ingroup in some way. Important to intergroup threat theory is that the threat perceptions are subjective and based on the individual's convictions—what some people see as threatening, others do not. The previous research has suggested that individual-level differences influence who perceives immigration as a threat. One such factor is the trait right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) (Altemeyer, 1981), which is characterized by an emphasis on submission to authority and upholding norms of social order. People high in RWA have been shown to harbor more negative attitudes toward immigration (Peresman et al., 2021). The “aggression” dimension of the right-wing authoritarian scale (Altemeyer, 1998; Sibley and Duckitt, 2008) has been particularly strongly connected to perceiving immigration as a threat (Peresman et al., 2021) and willingness to protect the ingroup from perceived outgroup threats (Gaertner et al., 2000).

Because RWA emphasizes protecting ingroup norms from external group threats, negativity may extend not only to immigrants but also to political opponents perceived as responsible for immigration and its consequences. This is in line with radical right party rhetoric, which often fuses the threat of immigration with blaming the parties that comprise the political establishment (Rydgren, 2007; Carter, 2018; Harteveld et al., 2021). We argue that those individuals who are high on authoritarian aggression are more likely to distance themselves from political opponents when they are concerned with the consequences of immigration. That is, affective polarization is likely to increase when individuals not only view immigration negatively but also exhibit traits associated with a strong emphasis on the protection of ingroup identity and thus associate immigration with an intergroup threat.

To evaluate our claim, we use a large-scale representative survey performed among Swedish citizens (N = 898). In line with calls made in the previous literature (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019), we evaluate our hypothesis using multiple different measures of affective polarization. To this end, we analyze three commonly used measures of affective polarization; trait ratings, feeling thermometers, and a measure of social distance. We show that there is a main effect of immigration attitudes on affective polarization, such that more negative attitudes toward immigration are related to higher affective polarization. This effect is moderated by the aggression dimension of RWA, such that being high in aggression strengthens the effect of anti-immigration attitudes on affective polarization. Hence, the individuals who have a strong tendency toward the protection of their ingroup identity (who are high in RWA aggression) are clearly more likely to distance themselves from their political opponents. This effect is robust for controlling for political ideology, suggesting that RWA aggression is important to consider when explaining affective polarization for some individuals. Our results suggest that individuals who are more sensitive to ingroup threats are more likely to become biased and hostile toward supporters of other political parties when they are concerned with immigration. The results are consistent across the three different measures of affective polarization, though the strength of the effect that varies across these measures.

Theoretical Framework

In studies of the USA, affective polarization has been defined as the “tendency of people identifying as Republicans or Democrats to view opposing partisans negatively and co-partisans positively” (Iyengar and Westwood, 2015, p. 691). In more general terms, Republicans and Democrats can be exchanged with any analogous in- and outgroups based on partisanship. Importantly, this definition entails a difference in how individuals evaluate their ingroup compared to their outgroup in a way that favors the ingroup. However, such evaluations could have very different content, and this is reflected in the previous research where a host of different methods have been used to assess affective polarization (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019; Iyengar et al., 2019).

Affective polarization is rooted in social identity theory (SIT) (Tajfel and Turner, 1979, 1986) and the idea that partisanship constitutes a psychological group membership (Iyengar et al., 2012, 2019). Social identity theory is one of the most influential theories in social psychology, describing how individuals' own identities fuse with groups to which they feel emotionally and psychologically attached. Accordingly, these groups become significant parts of the own self-view and definition of oneself and consequently become subject to group-serving and group-differentiating biases. Hence, the social identity theory provides a means to understand intergroup attitudes, feelings, and behaviors (Tajfel and Turner, 1979).

Much of the existing literature trying to identify determinants of affective polarization has focused on correlates at the system-level (Lauka et al., 2018; Boxell et al., 2020; Reiljan, 2020) or party-level (Gidron et al., 2020), although some of the recent studies have focused on evaluating the individual-level determinants of the affective polarization (Harteveld, 2021; Reiljan and Ryan, 2021; Wagner, 2021). The previous research has identified two main individual-level drivers of affective polarization. First, because the political group attachments may function as a social identity, strengthening group identification increases intergroup differentiation, which manifests as affective polarization (Iyengar et al., 2012; Mason, 2015; Webster and Abramowitz, 2017; Reiljan and Ryan, 2021). Second, the previous research has shown that if political attitudes are ideologically more extreme, the individuals become more affectively polarized (Rogowski and Sutherland, 2016; Webster and Abramowitz, 2017; Harteveld, 2021; Lelkes, 2021). Both ideas have received empirical support in the USA and some multiparty systems (Webster and Abramowitz, 2017; Renström et al., 2020; Harteveld, 2021; Reiljan and Ryan, 2021).

As mentioned, we add to the literature on the causes of affective polarization by arguing that the perceived threats toward the individual's ingroup can spur such partisan hostilities and bias (see also Renström et al., 2021). In line with the findings of the previous literature, we recognize that both identity and ideology are important determinants of the affective polarization. However, even among partisans with similar ideological positions and the same degree of partisan identity, we expect to see differences in affective polarization related to their perceptions of threats to their ingroup.

To build this argument, we draw on intergroup threat theory (Stephan et al., 2009), which claims that perceived threats against the ingroup increase intergroup distancing and negativity toward an outgroup. In line with this idea, perceived threats to the ingroup have been shown to increase affective polarization (Renström et al., 2021). One important aspect of intergroup threat theory is that threats are not objective properties but subjectively perceived. This means that what is perceived as a threat may differ between individuals—what some people see as a threat, others do not (Stephan et al., 2015).

Since cultural issues have been stressed as causing affective polarization (Gidron et al., 2020), we, in this study, focus on the issue of immigration as a potential threat. We present an argument suggesting that some individuals are more likely to perceive immigration as a threat to their ingroup, which can cause intergroup distancing and affective polarization. We do not expect all people to perceive immigration as threatening, but rather some individual-level characteristic is decisive for those who see immigration as threatening. The framing of immigration as threatening often taps into cultural values (Mudde, 2007; Harteveld et al., 2021), and cultural, more than economic, concerns seem to motivate the anti-immigration attitudes (McLaren and Johnson, 2007; Sides and Citrin, 2007; Hainmueller and Hopkins, 2014). Therefore, individuals who most likely perceive immigrants as threats to the values of their cultural group identity tend to react with most hostility against the immigrants (Peresman et al., 2021).

However, we are here interested in affective polarization, which entails distancing to other outgroup(s) than the one posing the perceived threat. We argue that while immigrants may be seen as the ones composing the threat, opposing political parties are also constructed in a negative light. Renström et al. (2021) find that people concerned about immigration show higher levels of affective polarization when they identify as right on a left–right political spectrum. However, left–right position does not directly measure sensitivity to threats toward cultural values. In this study, we argue that RWA (Adorno et al., 1950; Altemeyer, 1981; Feldman, 2003), another widely used measure, more directly captures individual concern for cultural values, which leads to perceptions of immigration as threatening and, by extension, the affective partisan attitudes these attitudes foster.

Right-wing authoritarianism is an ideological belief system that entails submission to authorities, conformity to norms that are seen as legitimate, and aggressive actions on behalf of these authorities against individuals that deviate from the norms. As RWA entails people value group norms, cohesion, and stability, it has been linked to an emphasis on protecting the ingroup from perceived cultural threats (Duckitt, 1989; Feldman and Stenner, 1997; Feldman, 2003), and it also predicts the perception of cultural threat stronger than other kinds of threats (such as economic) leading to anti-immigrant attitudes (Jedinger and Eisentrout, 2020). According to Duckitt and Sibley (2007), the reason for this is that RWA primarily predicts prejudice against outgroups that are perceived to challenge the prevailing normative order, which immigrants, particularly those from distant cultures, have the potential to do. Right-wing authoritarianism also seems to increase the susceptibility to threatening cues (Cohrs and Asbrock, 2009).

Right-wing authoritarianism is often characterized as a three-faceted concept, including aggression, submission to authority, and conventionalism, though it is most often used as a single measure (Funke, 2005; Duckitt et al., 2010). Earlier research shows that the aggression dimension, which focuses on the enforcement of ingroup norms, is the most predictive of negative immigrant attitudes (Peresman et al., 2021). This is particularly so when immigration groups are culturally distant, suggesting that the culturally distant immigrant groups activate authoritarian predispositions to protect the ingroup from the cultural threats that may challenge the existing social norms (Peresman et al., 2021). Hence, the aggression dimension of RWA may capture the traits influencing individual sensitivity to potential cultural threats posed by immigration.

We argue that the individuals who are negative toward immigration should show higher levels of affective polarization to the extent that they are high in the aggression dimension of RWA because the latter is associated with interpretation of immigration as a cultural threat. We thus formulate a conditional hypothesis in which we expect the following:

Individuals who are negative toward immigration will show higher levels of affective polarization when they are high in right-wing authoritarian aggression.

Methods

To evaluate our hypothesis, we performed a survey in Sweden in August 2020. Sweden is a multi-party system, resulting from a proportional electoral system consisting of eight parliamentary parties: the socialist Left Party, the Social Democrats, the Greens, the Liberals, the Center Party (former Agrarian Party), the Moderate Party (Conservatives), the Christian Democrats, and the Sweden Democrats (radical right). At the time of our data collection, the Social Democrats and the Green Party formed a minority government, supported by the Center Party, the Liberals, and the Left Party.

The populist right-wing Sweden Democrats entered parliament in 2010 and has since grown to become the third-largest party in 2018. The party has its roots in the more extreme nationalist movements but has recently overcome its “pariah” status with some parties on the right opening up for cooperation with them (the Moderate party and the Christian democrats). As a successful populist radical right party, the Sweden Democrats are similar to other such parties across Europe. Their main political agenda mainly concerns immigration, and they emphasize that the governing parties, or “establishment,” should be blamed for the problems with immigration (Hellström et al., 2012). Hence, like other right-wing populist parties, they stress both group divides of natives vs. non-natives and the people vs. the elite (Rydgren, 2007; Carter, 2018; Harteveld et al., 2021). In conjunction with the success of the radical right, cultural issues have become a major part of the political agenda, moving Swedish politics away from the dominance of the left–right/economic dimension. Some evidence suggests that the Swedish party system may be growing in polarization on these globalization and cultural issues, with the Sweden Democrats being placed far away from the other parties (Lindvall et al., 2017, p. 75).

Data was collected by the survey company Enkätfabriken, using Norstat online panels in August 2020. The sample was drawn to be representative based on age, gender, and area of living. A total of 1,093 participants responded. Mean age was 49 (SD = 16.81, range 18–83). There were 515 women (47.1%) and 492 men (45%); 4 (0.4%) non-binary1 and 82 (7.5%) missing2. Education was assessed on a six-graded scale as follows: 1 = not completed basic schooling (n = 2; 0.2%), 2 = basic schooling (n = 50; 4.9%), 3 = upper secondary school (n = 321; 31.4%), 4 = vocational training (n = 118; 11.5%), 5 = university/college degree (n = 513; 46.9%), and 6 = doctoral degree (n =19; 1.9%). The sample was slightly higher educated and older than the general population.

Measuring Affective Polarization

The most common way to measure affective polarization, outside the USA context, is to use scales where the participant indicates their feelings toward in- and outgroup parties or partisans or scales that measure the extent to which one likes or dislikes these (Lelkes and Westwood, 2017; Druckman and Levendusky, 2019; Boxell et al., 2020; Wagner, 2021). While these measures capture differences between the in- and outgroup evaluations, other measures are designed to capture the group-based biases in such evaluations more directly. In research on the USA case, a common measure is to ask participants to rate the parties or their supporters on different traits such as intelligence, honesty, open-mindedness, selfishness, and hypocrisy (Iyengar et al., 2012; Garrett et al., 2014; Druckman and Levendusky, 2019). Finally, a measure that is designed to capture how comfortable people are in having close interpersonal relations with supporters of another party, focusing on social distance, asks how one would feel if one's child was marrying someone from another party (Iyengar et al., 2012; Levendusky and Malhotra, 2016; Knudsen, 2021). While all these measures are commonly used, they are rarely measured simultaneously, which would aid in understanding how they are related (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019).

In this study, we have chosen to measure affective polarization using all of the three commonly used indicators of affective polarization, trait ratings, social distance, and feeling thermometers (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019). First, participants indicated their own preferred party with the question, “Which party do you best prefer today?” They were shown a list of the eight parties in the Riksdag (the Swedish parliament) and were also given a choice to indicate another party.3 This variable is used to identify the respondent's ingroup affiliation. Then respondents were asked to rate all the parties' supporters on four different traits. The traits were honest, intelligent, prejudiced, and selfish and the question read as “To what extent do you consider supporters of the following parties to be [trait]?,” with responses on an 8-point Likert scales from 1 = very little to 8 = very much. Our social distancing measure is based on the question, “How upset would you be if you had a daughter or son who married a supporter of the following parties?” For each party, participants indicated how upset they would be on a scale from 1 = not upset at all to 8 = very upset. Finally, the feeling thermometer asked participants, “What feelings do you generally have for supporters of the following parties?” For each party, participants indicated on a scale from 1 = very cold feelings to 8 = very warm feelings, their feelings.

Ingroup ratings are subtracted from outgroup ratings to create mean indices where higher values indicate more bias (increased distancing) in favor of the ingroup. For each participant, we calculate separately, for each outparty, the differences between the evaluation of the preferred party and all other parties on each provided attribute. From these differences, we calculated over the different attributes to create the index for polarization on positive traits (honest and intelligent) and on negative traits (selfish and prejudiced). The averages of the positive and the reversed negative indices were calculated, resulting in several polarization indices per participant—one for each outparty. The total polarization index is the mean of the differences between the ingroup and the outgroup ratings for every participant. Higher values on the polarization index indicate stronger intergroup differentiation in favor of the ingroup, between the ingroup and all outgroup parties. The polarization indices can range from −7 to +7, where 0 indicates that the participant makes no difference between the outgroup and the ingroup. Again, a negative value signifies outgroup preference, that is, a higher (more positive) rating on the outgroup compared to the ingroup. Positive values indicate ingroup favoritism, or more positive ratings of the ingroup compared to the outgroup.

Measuring RWA and Other Predictors

The main independent measures were RWA and anti-immigrant attitudes.

Right-wing authoritarianism was measured with four items assessing the aggression dimension taken from previous scales (Sibley and Duckitt, 2008): “Our society does NOT need a tougher government and stricter laws” (R); “Facts show that we must strike down harder on crime to keep moral and order”; “The police should avoid violence against suspects” (R); “It is necessary to use violence against people or groups that constitute a threat against authorities.” Responses were made on 7-point scales from 1 = do not agree at all to 7 = completely agree. Cronbach's alpha was good, 0.72. The generally accepted cut-point is 0.70 (Lance et al., 2006). The removal of any item decreased alpha.

Anti-immigrant attitudes were measured with seven items previously used in surveys by the society, opinion, and media institute at the University of Gothenburg, who performs annual surveys of the Swedish population (https://www.gu.se/en/som-institute). Some sample items are “I don't want people from other cultures as neighbors”; “I know many people who think that the problems with immigration is the most important social issue”; “Immigrants in Sweden should be guaranteed the same living standard as the rest of the country's population” (R).4 Responses were assessed on 7-point scales from 1 = do not agree at all to 7 = completely agree. Cronbach's alpha was high, 0.84.

The control variables included age, gender (coded woman = 0, man = 1), education (treated as an interval level variable), strength of partisanship, interest in politics, and left–right position. Strength of partisanship has been shown to strongly influence affective polarization (Renström et al., 2020). The question read as “Do you consider yourself to be a convinced supporter of this party [referring to the question of the participant's favorite party]?” Answers were assessed on a 3-point scale where 1 = yes, very convinced, 2 = yes, somewhat convinced, 3 = no. This variable was reverse coded to facilitate interpretation such that higher values indicated stronger partisanship, and it was treated as an interval-level variable in the analyses. Political interest was measured using the item “How interested are you in politics?” Answers ranged from 1 = not at all to 10 = very much. Political position was assessed using a left–right scale, where 1 = clearly to the left and 10 = clearly to the right.

Empirical Analyses

Descriptive Analyses

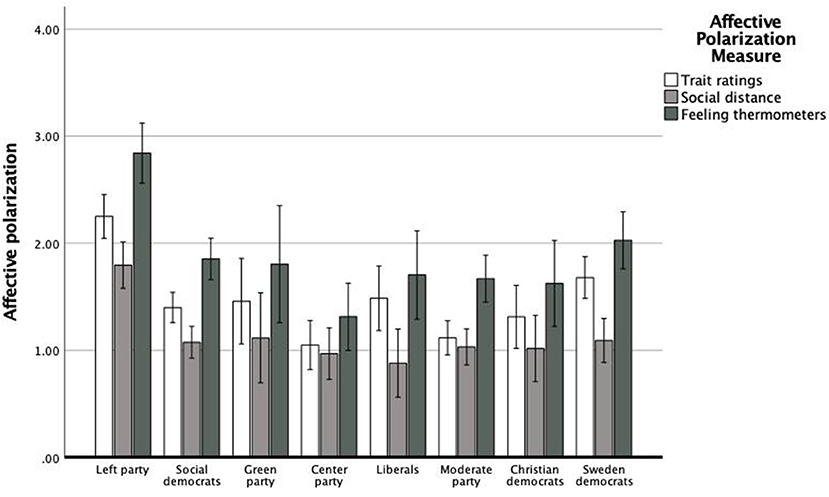

The mean level of affective polarization was Mtraits = 1.44, SDtraits = 1.21; Mfeelings = 1.88, SDfeelings = 1.62; and Mdistance = 1.13, SDdistance = 1.23. These means were all significantly higher than 0, which would indicate no difference in ratings between the inparty and the outparty ts > 38.45, ps < 0.001, Cohen's Ds > 0.91. We then illustrate how affective polarization plays out across the different parties for each of the three measures of affective polarization. Figure 1 shows affective polarization across all outgroup parties divided by the participant's own preferred party. The bars are all positive, indicating ingroup bias in ratings of the own and other parties (i.e., more favorable ratings of the inparty compared to the outparty). The confidence intervals do not cover 0 and hence all means are significantly larger than 0. Hence, all partisans are affectively polarized, regardless of how affective polarization is measured. The strongest polarization is displayed by supporters of the Left Party.

Figure 1. Mean affective polarization across participant's preferred party for all three measures of affective polarization. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

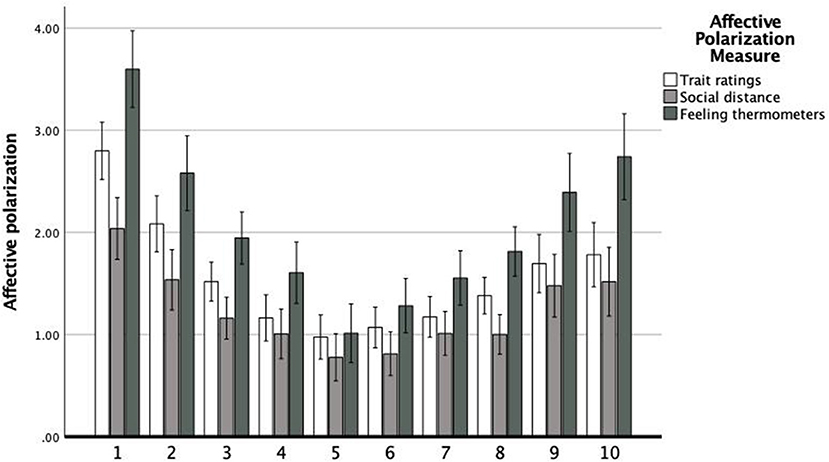

In Figure 2, we show how affective polarization plays out across the left–right scale from 1 = Clearly to the left to 10 = Clearly to the right. As can be seen, the participants who see themselves as clearly to the left are the most affectively polarized, and there is a clear trend that the more centrist partisans are less affectively polarizing. The trend goes up for people clearly to the right, but not as much as for those to the left.

Figure 2. Mean affective polarization across left–right for all three measures of affective polarization. 1 = clearly to the left; 10 = clearly to the right. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Main Analyses

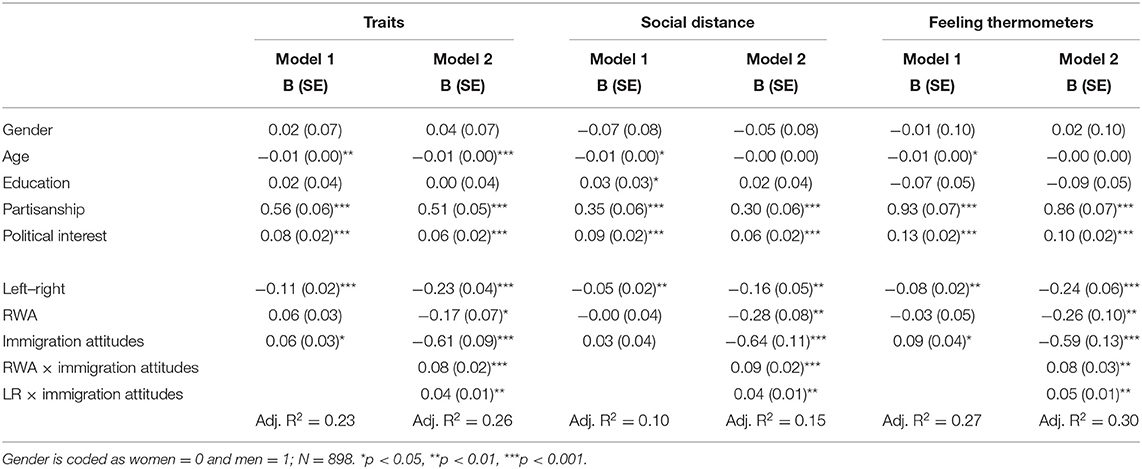

To evaluate our hypothesis that RWA aggression moderates the effect of anti-immigration attitudes on affective polarization, we ran a series of regressions. In Model 1, we include the background variables gender, age, education, partisanship, and left–right placement, and our focal predictors, RWA aggression and immigration attitudes. In Model 2, we entered the interaction between RWA and anti-immigration attitudes. To clearly isolate the effects of RWA aggression compared to a more general right-wing ideological position, we included the interaction between left–right self-placements and anti-immigration attitudes in our models as well.5 We present Models 1 and 2 for each outcome variable—that is, for each of the three measures of affective polarization, focusing on traits, social distance, and feeling thermometers. The results are shown in Table 1.

As can be seen in Table 1, there were no effects of gender on any of the outcome measures. There was a weak effect of age on the trait ratings and feeling thermometers such that older people were less affectively polarized. There was also a weak effect of education on the social distance measure such that higher education was related to more polarization on this outcome. In general, the effects of the demographic control variables were small and not substantively significant. In contrast, there were strong effects of partisanship, indicating that stronger support for the favorite party was related to higher levels of affective polarization, on all outcomes. This is in line with the previous results (Renström et al., 2020; Reiljan and Ryan, 2021). Political interest was also predicting all outcomes such that more political interest was related to higher affective polarization. Identifying more to the left on a left–right spectrum was associated with higher affective polarization on all outcome measures.

Being more negative toward immigration was related to higher levels of affective polarization on trait ratings and feeling thermometers, but not social distance. Right-wing authoritarianism aggression was not related to affective polarization on its own, regardless of which outcome measure we use.

The first model for each dependent variable, without the interaction terms, explained 23, 10, and 27% of the variation in affective polarization, respectively, for the trait ratings, social distance, and feeling thermometers. Overall, the social distance measure is explained to a lesser extent by the variables included in these models. This is not surprising since social distance is assumed to measure behavioral intentions (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019), which differs from attitudes or stereotypes.

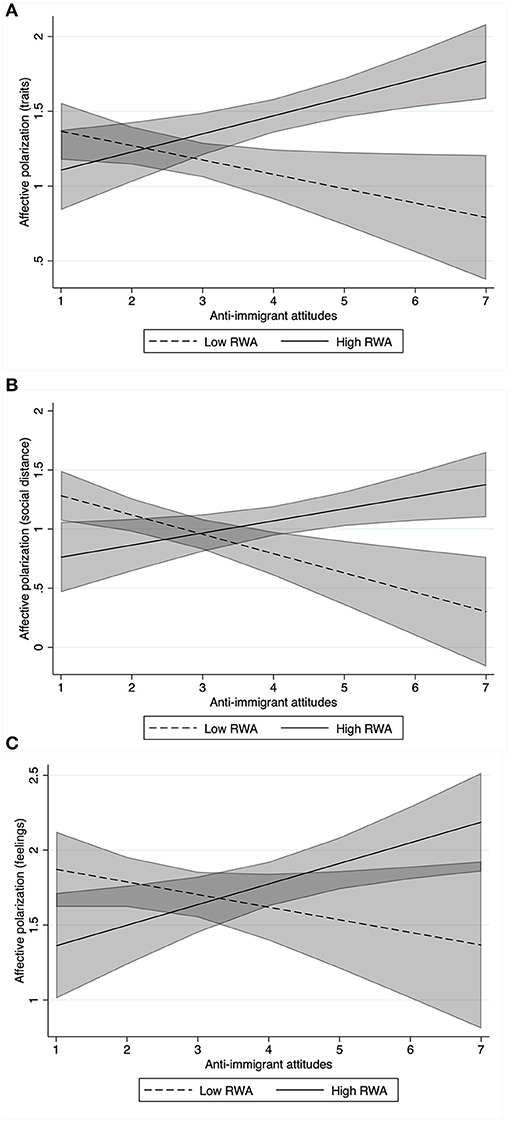

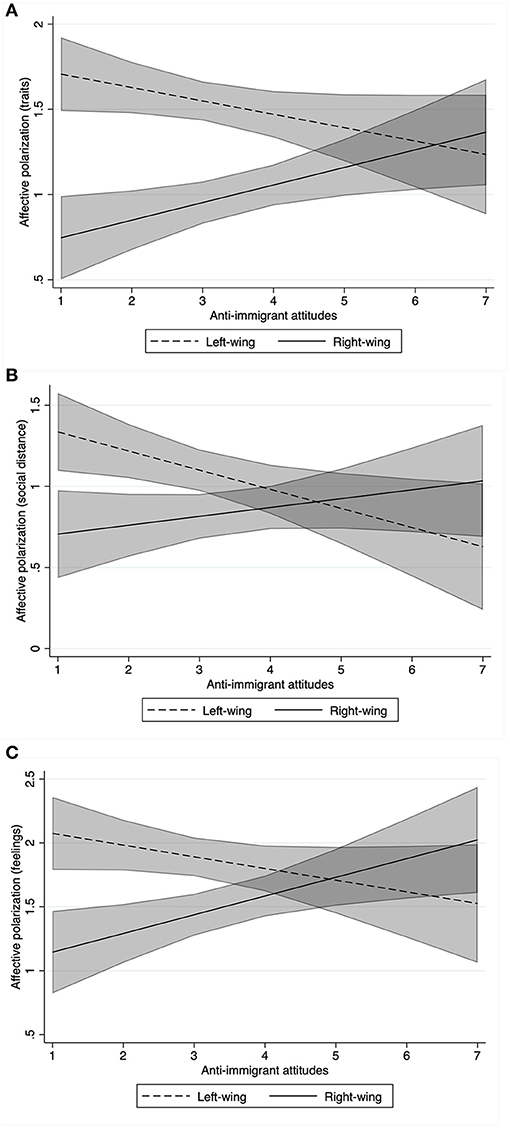

In the second model for each measure, we entered the interaction terms between anti-immigration attitudes and RWA. We also included the interaction between left–right identity and anti- immigration attitudes as a control. The interaction between anti-immigration attitudes and RWA was significant for all three outcome measures. The results are illustrated in Figure 3, where the slopes for RWA are set at 1 SD above and below the mean, and 95% confidence intervals are plotted around the slopes. The interaction between left–right identity and anti-immigration attitudes was also significant and is plotted in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Interactions between anti-immigrant attitudes and RWA on trait ratings (A), social distance (B), and feeling thermometers (C). Confidence intervals are 95%. Slopes are plotted at 1 standard deviation above and below the mean of RWA.

Figure 4. Interactions between left–right identity and anti-immigrant attitudes on trait ratings (A), social distance (B), and feeling thermometers (C). Confidence intervals are 95%. Slopes are plotted at 1 standard deviation above and below the mean of left–right identity.

For the all three outcome variables, the slopes for those high in RWA (1 SD above the mean of RWA) was significant, Btraits = 0.12, SEtraits = 0.04, ptraits = 0.002; Bdistance = 0.10, SEdistance = 0.04, pdistance = 0.02; Bfeeling = 0.14, SEfeeling = 0.05, pfeeling = 0.008. Hence, our hypothesis was confirmed; individuals who are negative toward immigration show higher levels of affective polarization when they are high in RWA aggression. While the results largely mirror each other, there are important differences. For both the social distance measure and the feeling thermometers, the confidence intervals are larger, and for the feeling thermometers, they actually overlap across the entire spectrum of anti-immigration attitudes indicating that there is no significant difference between the slopes, that is, the effect of anti-immigration attitudes on affective polarization for those high and low in RWA.

The substantive effects of the interaction between RWA aggression and anti-immigrant attitudes (see Figure 3A) shows that for a value of anti-immigrant attitudes of 5 (roughly the mean + 1 SD), the difference between individuals with a high and a low value on the RWA aggression scale (1 SD above and below the mean of RWA) is a little more than 0.5 scale point on the affective polarization measure for trait ratings. This should be seen in relation to the overall mean of affective polarization when using the trait ratings, which is 1.44.

While we did not have a hypothesis about individuals low in RWA aggression, we ran analyses for these slopes as well. The slopes for individuals low in RWA aggression (1 SD below the mean) was significant for trait ratings and the social distance measure, Btraits = −0.10, SEtraits = 0.05, ptraits = 0.04; Bdistance = −0.16, SEdistance = 0.05, pdistance = 0.002, but not for the feeling thermometers, Bfeeling = −0.08, SEfeeling = 0.06, pfeeling = 0.18. This means that for the individuals who are low in RWA aggression, they become less affectively polarized as they become more negative to immigration. This unexpected finding is further discussed below.

For comparison, we also analyzed the significant interactions between left–right identity and anti-immigration attitudes. The plots for these analyses are shown in Figure 4. These results confirm that the left and right ideological positions do not differentiate those with anti-immigration attitudes; however, the same is not true for those with pro-immigration attitudes. For the trait ratings and feelings, the slope for those identifying to the left (1 SD below the mean) was not significant, Btraits = −0.08, SEtraits = 0.04, ptraits = 0.075; Bfeeling = −0.09, SEfeeling = 0.06, pfeeling = 0.114, but it was for the social distance measure, Bdistance = −0.12, SEdistance = 0.05, pdistance = 0.015. All slopes are negative, indicating that as people who identify as left become more negative toward immigration, they also polarize less. On the contrary, people who are positive toward immigration and identify as left show higher affective polarization.

We also ran the corresponding slope analyses for those identifying themselves as to the right (1 SD above the mean of left–right identity). The slopes were significant for trait ratings and feeling thermometers, Btraits = 0.10, SEtraits = 0.04, ptraits = 0.016; Bfeeling = 0.15, SEfeeling = 0.06, pfeeling = 0.01, but not for the social distance measure, Bdistance = 0.05, SEdistance = 0.05, pdistance = 0.251. Hence, in line with the results for RWA, individuals who are negative toward immigration show higher levels of affective polarization when they identify to the right. However, this effect was only seen for two of the outcome measures, trait ratings and feeling thermometers.

While the results for the RWA and the left–right identity as moderators are substantively similar, there are important differences. When inspecting the plots (comparing Figures 3, 4), it becomes clear that when using RWA as moderator, the effects, that is, the differences between the slopes, are restricted to those who are negative toward immigration (from about midpoint and above on the anti-immigration attitude measure), but when using left–right identity as moderator, the inverse is true. That is, the effects are restricted to those low in anti-immigration attitudes—that is, those positive toward immigration.

In line with the results for the interaction between RWA aggression and anti-immigration attitudes, the interactions between left–right identity and anti-immigration attitudes show the clearest results when using trait ratings as the outcome variable. Both other measures again have larger confidence intervals, indicating a larger spread of responses. This is noteworthy since the feeling thermometer is the measure that is by far the most commonly used in the previous work on affective polarization.

Concluding Discussion

This study set out to explore what may spur affective polarization. Based in social identity theory, affective polarization is an expression of biased group inferences entailing more favorable constructions of the ingroup and more negative constructions of the outgroup (Tajfel and Turner, 1986; Iyengar et al., 2019). In terms of affective polarization, such generalized constructions may include attributing negative traits to the outgroup and its members and attributing positive traits to the ingroup and its members (Iyengar et al., 2012; Garrett et al., 2014; Druckman and Levendusky, 2019). Another expression of affective polarization is exhibiting more negative feelings about the outgroup and more positive feelings about the ingroup (Lelkes and Westwood, 2017; Druckman and Levendusky, 2019; Boxell et al., 2020; Wagner, 2021). Finally, affective polarization may manifest as social distancing—an unwillingness to have social relationships with members of the outgroup (Iyengar et al., 2012; Levendusky and Malhotra, 2016; Knudsen, 2021). Regardless of how affective polarization manifests, the basic mechanisms rooted in social identity theory should be the same.

Based in the social identity theory, intergroup threat theory (Stephan et al., 2009, 2015) claims that perceived threats to the ingroup lead to increased efforts to defend the ingroup. These efforts could manifest as affective polarization. We thus hypothesized that affective polarization would increase as a consequence of perceiving a threat. This is also what we found. We explored how attitudes toward immigration interacted with the aggression dimension of the RWA scale (Altemeyer, 1998; Sibley and Duckitt, 2008) and found that individuals highly negative toward immigration showed higher affective polarization when also exhibiting higher RWA aggression. One way to understand this interaction is that those who are both negative toward immigration and high in RWA perceive immigration as threatening to the cultural values and norms. Since it is opposing political groups—the political establishment and cosmopolitan left—associated with enabling immigration, these political opponents are also seen as a threatening outgroup from which one must distance oneself. This result is important for understanding how populist right-wing rhetoric may fuel not only sentiments such as negative attitudes toward immigration but also a deep animosity against other partisans. Hence, our results suggest that individuals most likely draw inferences that stretch beyond the immediate situation and develop affective attitudes based on political responsibility for salient threats. We have argued that the combination of high RWA aggression and high anti-immigrant sentiments is indicative of perceiving immigration as a threat and that blame is attributed to the parties that may be seen as facilitators of immigration. This leap from the perceived source of the threat to the facilitators requires both knowledge and cognitive capacity. That we find effects for the interaction while also controlling for several important predictors tells us that the results have relevance. While we believe this is a valid interpretation, it would also be useful to investigate more direct measures of group blame to ensure that people do, in fact, make such cognitive leaps.

In this study, we suggest that it is likely the cultural threat of immigration that likely drives the effects, but do not rule out that polarization can also be motivated by the economic threat of immigration. We chose the RWA scale because it is designed to tap into how people feel about others that violate the norms in one's society. As such, RWA aggression can be interpreted as capturing sensitivity to immigration as bringing different cultural influences perceived to violate the existing norms and worldview of the host society and has shown to correlate with culturally-biased immigration attitudes (e.g., Peresman et al., 2021). Still, this is not a strict test that would show definitively that cultural rather than economic concerns motivate affective polarization.

Our results provide an important explanation for the significance of cultural conflicts for the emergence and growth of affective polarization. The pathway we emphasize is one in which cultural threats to an ingroup identity should motivate a tendency to attribute responsibility for harming core values and, thus, fundamental demonization of the opponents. While both policy disagreement and social identities have been seen as causes for affective polarization, this study illuminates how they may interact. Specifically, salient cultural policy issues interact with individual tendencies toward protecting social identities to substantially enhance the probability of engaging in the intergroup distancing that forms the basis of affective polarization.

Several other interesting findings emerged from this study. One finding relates to individuals who are low in RWA aggression. Research on RWA focuses on the characteristics of people high in RWA (see, e.g., Altemeyer, 1996), but provides less clarity about what low values entail. Therefore, understanding the implications of the results for low RWA individuals is not straightforward. Capturing analogous concepts of threat perception using measures more versatile than RWA will be important to understanding the full range of individual characteristics associated with affective polarization. When looking at the results for ideological identification, we found that the individuals who were highly positive to immigrants showed higher affective polarization as a consequence of increased left-wing identification. It could be argued that this is rooted in the same idea of individual sensitivity for perceiving a threat and translating this into affective polarization. People who do not perceive immigration as threatening may find the political groups that want to limit immigration threatening to their view of democratic values and human rights. Crawford (2014) observed a concern about right-wing groups infringing on rights and freedom of others, among those who consider them their least-liked group, threatening values that can be linked to egalitarianism and left-wing beliefs (Cohrs et al., 2005; Crawford et al., 2013). The rise of populist radical right parties and their use of anti-immigrant and anti-establishment rhetoric increases the likelihood that the party itself and its supporters are perceived as threatening the core democratic values. In one study, people who expressed concerns about the state of the democracy became increasingly affectively polarizing as their left-wing identification increased (Renström et al., 2021). While left-wing orientation is not a parallel construct to RWA, there is not currently an established measure of such a construct (Altemeyer, 1996; Conway et al., 2017; Costello et al., 2020) and should be a focus of future research.

Overall, these results are important as they indicate that tendencies toward affective polarization are dependent on what different individuals find to be threats and who they perceive as the threatening group. Although consistent with prior research (e.g., Webster and Abramowitz, 2017; Reiljan and Ryan, 2021), the most important predictor of affective polarization is the strength of partisanship; the results shed additional light on the causes of affective polarization. The substantive effects show that for an individual who is highly negative to immigrants, the effect of being high vs. low in right-wing authoritarian aggression is about half a scale point in affective polarization (for the trait ratings). This effect holds when controlling for important predictors of affective polarization analyzed in the previous literature.

In addition to providing an answer to what influences affective polarization, our results also provide insight into the differences among three different commonly used measures of affective polarization. While the results are substantively the same across measures, our results suggest that trait ratings best capture variations due to the interactions between anti-immigration attitudes and the moderator. The confidence intervals for these ratings are much smaller, indicating more consistency in the effects. This may be due to feeling thermometers being too inclusive to precisely capture the concept of affective polarization, and that social distance is in fact measuring another aspect of affective polarization than what is commonly intended. Given the popularity of these measures, especially the feeling thermometers that are easier to implement in surveys, the present results can be interpreted as supporting the use of feeling thermometers as indicators of affective polarization, while still warranting some caution.

In line with earlier research (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019; Renström et al., 2020), we see that the social distance measure contains more variability compared to trait ratings. This is not surprising since they are designed to capture different concepts. Trait ratings capture general attitudes, while social distance captures behaviors, and the two have repeatedly been shown to be weakly correlated (Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010; Druckman and Levendusky, 2019). Our results regarding differences in measurement have important consequences since most research, especially in the multi-party context has used feeling thermometers. The research on affective polarization and especially predictors of affective polarization is at an early stage and the way the concept comes to be conceptualized will have consequences for what features will be able to capture variation. The results presented in this study suggest that out of the three measures used in this study, the trait ratings seem to best capture biases in evaluations of in- and outgroup members. It is thus important for the individual researcher to consider which of the different measures is best suited to their needs (see also Druckman and Levendusky, 2019).

Regardless of what measure is used, the difficulties in conceptualizing affective polarization are multi-faceted. One facet concerns whether polarization should be seen as a system-level or individual-level feature. As we discussed initially, we take the view of Iyengar and Westwood (2015) arguing that affective polarization is essentially a form of biased evaluations of the in- and outgroup that stems from social identity (Iyengar et al., 2019). As such, we would argue that this is an individual-level process influenced by social and cognitive aspects. While we suggest that this general tendency is universal, we also think that the system-level features could influence affective polarization. For instance, in a two-party system, it may be easier to emphasize differences between groups than in a multi-party system where the need for alliances and co-governing may lead to emphasis on similarities. While this is not a question we can resolve in this study, it clearly deserves attention in the future research.

While the results are important for how researchers should conceptualize affective polarization, how the ingroup and outgroup are operationalized is also relevant. Most previous research that has used the trait ratings to assess affective polarization has operationalized ingroup membership in terms of explicit statements of being supporters of one party. In this study, we have used a somewhat more inclusive definition where the participants are asked to specify their favorite party. This means that some individuals do not necessarily see themselves as supporters of the party they indicate as the most liked. We would expect this operationalization to lead to somewhat weaker results since partisanship is one feature that influences the strength of displayed affective polarization (Reiljan and Ryan, 2021). Hence, the operationalization of ingroup membership employed in this article may represent a more challenging one for testing our hypothesis about affective polarization.

Another issue of debate in the literature is how to define both the ingroup and the outgroup. To measure the ingroup status, we asked the participants to indicate what party they preferred the most. Some research has instead relied on questions asking how close the participant feels to different parties, which may be conceptually closer to capturing identity-based attachments to the ingroup. Yet, as the people tend to create identity-based attachments to arbitrary groups in line with the minimal group paradigm (Tajfel, 1970), we believe that our definition of the ingroup is not problematic. Nevertheless, defining and measuring an individual's ingroup is an important matter needing attention in future research.

To define the outgroup in our study, we opted to collapse all parties other than the respondents' favorite into one outgroup. While some parties in a multi-party context inevitably are closer than others (Bergman, 2020), we combine them all together into one outgroup measure. Alternatives operationalizing the outgroup in a multi-party context would include creating blocs of parties that are similar policy-wise or based on elite-level cultural disagreement (Gidron et al., 2020). One possibility for future research may be to ask participants to indicate their least favored party and create affective polarization scores between the most and least favored parties, which would yield analyses more similar to the USA two-party context. These alternative approaches may yield stronger effects.

The results in this study could be further replicated and strengthened in future research. One way would be to explore if there are survey items in other data sets that could be used as proxies for the authoritarian aggression variables we have used in this original survey. It would be beneficial to explore to what extent the results found here replicate across time and countries. Though the issue of immigration has been a salient issue among Swedish voters since the 2015 “refugee crisis,” at the time of data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic (August, 2020), the immigration issue was not as salient as in the previous years. It is possible that the impact of our main variables would be stronger in contexts where the immigration issue is more salient.

Finally, we note that our measure asked participants to evaluate supporters of the other parties and not party elites or the party in general. Some research shows that people dislike elites—who are the ones respondents imagine when asked about the parties—more than partisans (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019), which may mean that our measure yields weaker effects. However, asking participants to evaluate partisans allows our results to relate more directly to the polarized societal climate, which has broader consequences for how people interact and socialize.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/E859Y.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

ER, HB, and RC contributed to conception and design of the study. ER organized the database, performed the statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft of the article after joint discussions with HB and RC. HB and RC wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swedish Research Council, Grant No. 2017-02609.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.919236/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The non-binary were removed from analyses including gender due to the low n.

2. ^Gender was assessed with a free response text and then coded into men, women, and non-binary.

3. ^Participants who indicated some other party were excluded from the analyses (n = 75, 6.8%).

4. ^See Appendix in Supplementary Material for all items. Appendix in Supplementary Material also includes information comparing the sample of participants on their political affiliation with the most recent election results, and a table correlating all variables.

5. ^We also ran analyses separate for those high (≥5) and low (<4) on the 10-point left–right scale, and for the government and opposition parties separately. These are shown in the Supplementary Material.

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., and Sanford, R. N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. Harpers.

Bergman, M.. (2020). Sorting between and within coalitions: the Italian case (2001–2008). Ital. Polit. Sci. Rev. 51, 42–66. doi: 10.1017/ipo.2020.12

Boxell, L., Gentzkow, M., and Shapiro, J. M. (2020). Cross-country trends in affective polarization (No. w26669). National Bureau of Economic Research. doi: 10.3386/w26669

Carter, E.. (2018). Right-wing extremism/radicalism: reconstructing the concept. J. Polit. Ideol. 23, 157–182. doi: 10.1080/13569317.2018.1451227

Cohrs, C. J., Moschner, B., Maes, J., and Kielmann, S. (2005). The motivational bases of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation: relations to values and attitudes in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 31, 1425–1434. doi: 10.1177/0146167205275614

Cohrs, J. C., and Asbrock, F. (2009). Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and prejudice against threatening and competitive ethnic groups. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 39, 270–289. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.545

Conway, L.G. III., Houck, S.C., Gornick, L. J., and Repke, M. A. (2017). Finding the Loch Ness Monster: left-wing authoritarianism in the United States. Polit. Psychol. 39, 1049–1067. doi: 10.1111/pops.12470

Costello, T. H., Bowes, S. M., Stevens, S. T., Waldman, I. D., and Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020). Clarifying the structure and nature of left-wing authoritarianism. Psyarxiv 122, 135. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/3nprq

Crawford, J. T.. (2014). Ideological symmetries and asymmetries in political intolerance and prejudice toward political activist groups. J. Exper. Soc. Psychol. 55, 284–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2014.08.002

Crawford, J. T., Modri, S. A., and Motyl, M. (2013). Bleeding-heart liberals and hard-hearted conservatives: subtle political dehumanization through differential attributions of human nature and human uniqueness traits. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 1, 86–104. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v1i1.184

Druckman, J. N., and Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opin. Q. 83, 114–122. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfz003

Duckitt, J.. (1989). Authoritarianism and group identification: A new view of an old construct. Polit. Psychol. 10, 63–84. doi: 10.2307/3791588

Duckitt, J., Bizumic, B., Krauss, S., and Heled, E. (2010). A tripartite approach to right-wing authoritarianism: the authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism model. Polit. Psychol. 31, 685–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00781.x

Duckitt, J., and Sibley, C. G. (2007). Right wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice. Eur. J. Personal. 21, 113–130. doi: 10.1002/per.614

Feldman, S.. (2003). Enforcing social conformity: A theory of authortarianism. Polit. Psychol. 24, 41–74. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3792510

Feldman, S., and Stenner, K. (1997). Percieved threat and authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 18, 741–770.

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Funke, F.. (2005). The dimensionality of Right-wing authoritarianism: Lessons from the dilemma between theory and measurement. Polit. Psychol. 26, 195–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00415.x

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Banker, B. S., Houlette, M., Johnson, K. M., and McGlynn, E. A. (2000). Reducing intergroup conflict: from superordinate goals to decategorization, recategorization, and mutual differentiation. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 4, 98–114. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.4.1.98

Garrett, R. K., Gvirsman, S. D., Johnson, B. K., Tsfati, Y., Neo, R., and Dal, A. (2014). Implications of pro- and counter-attitudinal information exposure for affective polarization. Hum. Commun. Res. 40:309–332. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12028

Gidron, N., Adams, J., and Horne, W. (2020). “American affective polarization in comparative perspective,” in Elements in American Politics (Cambridge: University Press). doi: 10.1017/9781108914123

Hainmueller, J., and Hopkins, D. J. (2014). Public attitudes toward immigration. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 17, 225–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-194818

Harteveld, E.. (2021). Fragmented foes: affective polarization in the multi-party context of the Netherlands. Elect. Stud. 71, 102332. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102332

Harteveld, E., Mendoza, P., and Rooduijn, M. (2021). Affective polarization and the populist radical right: creating the hating? Govern. Oppos. doi: 10.1017/gov.2021.31. [Epub ahead of print].

Hellström, A., Nilsson, T., and Stoltz, P. (2012). Nationalism vs. nationalism: the challenge of the Sweden democrats in the Swedish public debate. Govern. Oppos. 47, 186–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2011.01357.x

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., and Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs038

Iyengar, S., and Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: new evidence on group polarization. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 59, 690–707. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12152

Jedinger, A., and Eisentrout, M. (2020). Exploring the differential effects of percieved threat on attitudes toward ethnic minority groups in Germany. Front. Psychol. 10:2895. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02895

Kalmoe, N. P., and Mason, L. (2022). Radical American Partisanship: Mapping Violent Hostility, Its Causes and the Consequences for Democracy. Chicago, IL: The University of Chigaco Press.

Knudsen, E.. (2021). Affective polarization in multi-party systems? Comparing affective polarization towards voters and parties in Norway and the United States. Scand. Polit. Stud. 44, 34–44. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12186

Lance, C., Butts, M. M., and Michaels, L. C. (2006). The sources of four commonly reported cutoff cirteria: What did they really say? Organ. Res. Methods. 9, 202–220. doi: 10.1177/1094428105284919

Lauka, A., McCoy, J., and Firat, R. B. (2018). Mass partisan polarization: measuring a relational concept. Am. Behav. Sci. 62, 107–126. doi: 10.1177/0002764218759581

Lelkes, Y.. (2021). Policy over party: comparing the effects of candidate ideology and party on affective polarization. Polit. Sci. Res. Method. 9, 189–196. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2019.18

Lelkes, Y., and Westwood, S. J. (2017). The limits of partisan prejudice. J. Polit. 79, 485–501. doi: 10.1086/688223

Levendusky, M., and Malhotra, N. (2016). Does media coverage of partisan polarization affect political attitudes? Polit. Commun. 33, 283–301. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2015.1038455

Lindvall, J., Bäck, H., Dahlström, C., Naurin, E., and Teorell, J. (2017). Samverkan och strid i den parlamentariska demokratin. Stockholm: SNS Förlag.

Mason, L.. (2015). “I disrespectfully agree”: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 59, 128–145. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12089

McLaren, L., and Johnson, M. (2007). Resources, group conflict, and symbols: Explaining anti-immigration hostility in Britain. Polit. Stud. 55, 708–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00680.x

Mudde, C.. (2007). The Populist Radical Right in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511492037

Peresman, A., Carroll, R., and Bäck, H. (2021). Authoritarianism and Immigration Attitudes in the UK. Political Studies. doi: 10.1177/00323217211032438

Reiljan, A.. (2020). Fear and loathing across party lines (also) in Europe: affective polarization in European party systems. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 59, 376–396. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12351

Reiljan, A., and Ryan, A. (2021). Ideological tripolarization, partisan tribalism and institutional trust: the foundations of affective polarization in the Swedish multiparty system. Scand. Polit. Stud. 44, 195–219. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12194

Renström, E. A., Bäck, H., and Carroll, R. (2021). Intergroup threat and affective polarization in a multi-party system. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 9, 553–576. doi: 10.5964/jspp.7539

Renström, E. A., Bäck, H., and Schmeisser, Y. (2020). “Vi ogillar olika. Om affektiv polarisering bland svenska väljare,” in Regntunga skyar, eds U. Andersson, A. Carlander and P. Öhberg (University of Gothenburg; SOM-institute)

Rogowski, J. C., and Sutherland, J. L. (2016). How ideology fuels affective polarization. Polit. Behav. 38, 485–508. doi: 10.1007/s11109-015-9323-7

Rydgren, J.. (2007). The sociology of the radical right. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 33, 241–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131752

Sibley, C. G., and Duckitt, J. (2008). Personality and prejudice: a meta-analysis and theoretical review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 12, 248–279. doi: 10.1177/1088868308319226

Sides, J., and Citrin, J. (2007). European opinion about immigration: The role of identities, interests and information. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 37, 477–504. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4497304

Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., and Morrison, K. R. (2009). “Intergroup threat theory,” in Handbook of Prejudice, ed T. Nelson (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum).

Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., and Rios, K. (2015). “Intergroup threat theory,” in Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination, 2nd edn, ed T. D. Nelson (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 255–278.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J.C. (1986). “The social identity theory of intergroup behavior,” in Psychology of Intergroup Relation, eds S. Worchel, and W. G. Austin (Chicago: Hall Publishers), 7–24.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds S. Worchel, and W. G. Austin (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole), 33–47.

Wagner, M.. (2021). Affective polarization in multi-party systems. Elect. Stud. 69, 102199. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199

Keywords: affective polarization, authoritarianism, immigration attitudes, survey, Sweden

Citation: Renström EA, Bäck H and Carroll R (2022) Protecting the Ingroup? Authoritarianism, Immigration Attitudes, and Affective Polarization. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:919236. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.919236

Received: 13 April 2022; Accepted: 15 June 2022;

Published: 14 July 2022.

Edited by:

Mariano Torcal, Pompeu Fabra University, SpainReviewed by:

Hugo Marcos-Marne, University of Salamanca, SpainFabian Jonas Habersack, University of Innsbruck, Austria

Luana Russo, Maastricht University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2022 Renström, Bäck and Carroll. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emma A. Renström, Emma.Renstrom@hkr.se

Emma A. Renström

Emma A. Renström Hanna Bäck

Hanna Bäck Royce Carroll3

Royce Carroll3