- 1Department of Dermatology, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan

- 2Department of Dermatology, Kansai Medical University, Hirakata, Japan

Urticaria is a symptom of acute skin allergies that is not clearly understood, but mast cell histamine is hypothesized to cause swelling and itching. Omalizumab, an anti-human IgE antibody that traps IgE and prevents its binding to high-affinity IgE receptors, is effective in treating urticaria. We recently experienced a case of urticaria refractory to antihistamine therapy in which the peripheral-blood basophil count responded to omalizumab therapy and its withdrawal. Furthermore, the peripheral-blood basophils showed an unexpected increase in the expression of a cell surface activation marker. This phenomenon has been reported by other analyses of basophil and mast cell dynamics during omalizumab treatment. Here, we analyze these observations and formulate a hypothesis for the role of basophils in urticaria. Specifically, that activated basophils migrate to the local skin area, lowering peripheral-blood counts, omalizumab therapy alters basophilic activity and causes their stay in the peripheral blood. We hope that our analysis will focus urticaria research on basophils and reveal new aspects of its pathogenesis.

Introduction

Urticaria is a common skin disease characterized by itchy, red, raised bumps or hives. It is generally classified based on its duration, acute (≦ 6 weeks) or chronic (>6 weeks), and the relevance of eliciting factors, spontaneous (no specific eliciting factor involved) or inducible (specific eliciting factor involved) (1). Based on these classifications, chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is diagnosed based a duration of over 6 weeks and the absence of identifiable eliciting factors.

The etiology and pathogenesis of CSU remain largely unexplored. However, there is a consensus that cutaneous mast cells play a major role by releasing histamine, which acts on blood vessels and nerves to cause swelling and provoke itching, respectively. Antihistamine is the standard treatment for urticaria and antihistamine-resistant patients are well-controlled with omalizumab, an anti-human IgE antibody, which reconfirms that IgE is important in the pathology of urticaria, even in CSU with unknown triggers.

Peripheral Blood Basophil Counts and the Disease Activity of CSU

We recently reported a case with a 6-year history of severe CSU, whose peripheral basophil count was persistently low (almost zero cells per µL) for more than 1 year (2). Upon urticaria resolution by omalizumab administration, we noticed that the peripheral basophil count had increased. When the patient discontinued omalizumab, the peripheral blood basophil count again dropped to zero and urticaria recurred. Restarting omalizumab rescued the peripheral blood basophil count and improved the skin rash. Before our observation, this inverse correlation with basophil count and urticarial activity has been confirmed by clinical trials of omalizumab (3) in which they quantified peripheral-blood basophils using blood histamine levels and flow cytometry. The study authors found that both parameters increased with omalizumab treatment and clinical CSU improvement.

The contribution of basophils to allergic reactions, acquired immunity, and autoimmune diseases is better understood (4, 5), though it was long ignored or confused with that of tissue-resident mast cells. This may be because basophils account for less than 1% of granulocytes in the peripheral blood and are phenotypically similar to mast cells. Both cell types have basophilic granules in their cytoplasm, high-affinity IgE receptors (FcϵRI) on their surface, and release histamine and other chemical mediators.

The fact that basophils express FcϵRI and release histamine, together with observation that the basophils in peripheral blood inversely correlate with urticarial rash severity, suggests that basophils play a role in CSU. Indeed, as omalizumab has become more frequently used in the treatment of CSU refractory to antihistamine therapy, a number of reports have examined potential predictors of its efficacy (6–10). Many studies have demonstrated that low total IgE levels are an essential marker for discriminating the efficacy of omalizumab. Fok et al. (9) found that low IgE levels in CSU patients did not respond to omalizumab or had only a weak effect, but there was no evidence to suggest which marker was effective. Aghdam et al. (10) evaluated whole blood leukocytes responses in CSU patients treated with omalizumab to elucidate the effect of omalizumab on different FcϵRI-bearing leukocytes, only percentage of basophil increased after omalizumab treatment, but other white blood cells remain stable. As for baseline characteristics of CSU patients, Johal et al. (6) reported higher symptom scores and slower symptom improvement with omalizumab treatment in those with decreased peripheral blood basophils than in those without, which is consistent with previous studies focusing on basopenia as a marker of disease severity (11). Rijavec et al. (7) reported that a very low number of absolute basophil count in the circulation (1.7 basophils/µL) is predictive of a poor response to omalizumab. Furthermore, low circulating basophils count significantly correlated with very low densities of FcϵRI and IgE on basophils. They also confirmed the basopenia using the low expression of basophil-related genes in the whole-blood genes, including FCER1A that codes α-chain of FcϵRI, CPA3 that codes carboxypeptidase A3, and HDC that involves histamine synthesis.

The phenomenon that basophils are inversely correlated with CSU severity is not specific to omalizumab treatment, as it was also observed in CSU patients treated with antihistamines (12). This report measured symptom severity using the daily baseline urticaria activity score; the more severe the symptoms, the lower the peripheral blood basophil count. Thus, the relationship between peripheral-blood basophils and urticaria severity is not treatment-method dependent.

In clinical practice, basophils account for a very small percentage of peripheral blood cells, which makes it difficult to define an expected value. However, basophil fluctuations can indicate urticaria activity, at least on a patient-by-patient basis.

A Basophil Activation Marker Increased After the Initiation of Omalizumab

Not only did omalizumab treatment affect peripheral-blood basophil levels (2), it also increased their surface expression of CD203c, which reflects the activation state of basophils (13). It seems a paradoxical phenomenon where peripheral circulating basophils appear to express more CD203c after successful omalizumab treatment. Of course, it is important to consider that CD203c expression is not equivalent to CD63 expression and is not a specific marker for degranulation. Its expression can be driven by IL-3 at least in vitro (14), besides IgE-FcϵRI cross-linking (15). Therefore, some reports suggest that CD203c expression is not a suitable index for assessing basophil activation in patients with CSU (14).

However, omalizumab has also been reported to enhance sensitivity of human basophils to IgE-mediated stimulation (16–21). Basophils collected from the patients with the sensitivity to cat allergens showed 3- to 125-fold more sensitive to antigen-driven secretion after the treatment with omalizumab (17). Nevertheless, the lack of change in responsiveness to non-IgE-mediated stimuli, e.g., to N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine, may be worth considering (18).

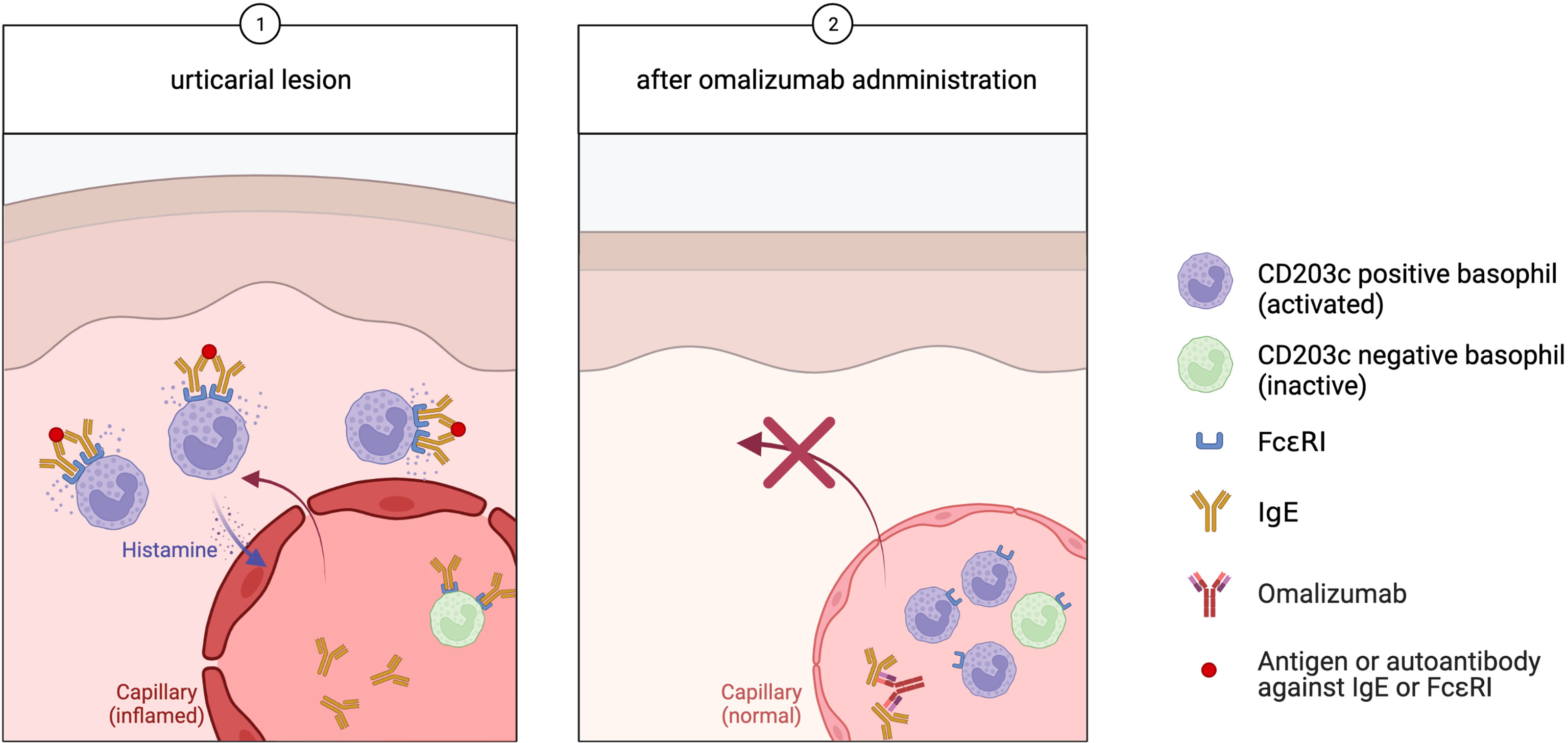

To explain this, we hypothesized that activated basophils migrate locally to the skin while patients experience CSU symptoms, and inactive or immature basophils unable to show sufficient activity in response to IgE-mediated stimulation remain in the peripheral blood (Figure 1, step 1). Once the CSU symptoms are relieved, the basophils with the ability to become fully activated in response to stimuli stay in the peripheral blood, increasing the frequency of peripheral blood basophils that express cell-surface CD203c.

Figure 1 In urticaria, (Step 1) activated basophils migrate to the skin lesions, while inactive basophils remain in the peripheral blood. (Step 2) Omalizumab binds free IgE, which prevents further basophilic activity and a corresponding decrease in FcϵRI expression. Activated CD203c-positive basophils stay in the peripheral blood, leading to an increase of the peripheral blood basophil population.

Basophil Infiltration of CSU Lesions

The BB1 antibody against human basophils has detected basophil infiltration into skin lesions (22–24). In CSU patients, the number of mast cells in autologous serum-induced wheals remains constant from about 30 minutes to 48 hours after development. However, the number of basophils was high at baseline compared to healthy skin and further increased by about 30 minutes after onset (23). Moreover, the immunohistochemistry analysis of autologous wheals revealed overlapping trends of IL-4 (possibly expressed by activated basophils) and the chemokine receptor CCR3, which are primarily associated with type 2 immune responses. The presence of these molecules peaked at 30 minutes, then began to decline, which suggests that these recruiting mechanisms might attract basophils early in the reaction (23).

The relationship between blood and tissue basophil counts has not been studied in detail. However, given the finding that blood basopenia is frequently observed in CSU patients (25), these reports of the identification of basophils at sites of inflammatory lesions suggest that the decrease in basophils is probably the result of migration of basophils from the circulation to the tissues.

Discussion

Unfortunately, the mechanism for omalizumab efficacy in urticaria is not clear (16). FcϵRI are also expressed on dendritic cells (DCs), potent antigen presenting cells, and eosinophils, and there are reports that omalizumab treatment actually deregulates FcϵRI expression on DCs (21), but it is assumed that mast cells and basophils are the main cells involved in the pathogenesis of CSU. Another evidence, as well, indicated that DCs do not play a principal role in CSU. Although a reduction in FcϵRI expression of CD1c in DCs after omalizumab treatment could be observed (10), this reduction did not correlate with clinical changes. It is well known that the expression of FcϵRI on the cell surface of mast cells is regulated by the amount of external IgE (26, 27). The same is true for basophils. This theory is supporting evidence that allergic reactions occur more quickly and severely upon a second exposure than it did after the first. The prevailing hypothesis is that omalizumab binds free IgE, which reduces FcϵRI expression on mast cells and basophils.

In atopic dermatitis patients, the omalizumab-dependent reduction of free IgE in the circulating blood is followed by the downregulation of basophilic FcϵRI expression as early as 3 days after the first dose (28). In allergic rhinitis patients, the FcϵRI expression on basophils had decreased by 88% on day 7 of omalizumab treatment, which is also when the acute allergen wheal size decreased (29). In CSU, and other allergic diseases, the mean basophil-bound IgE and basophil FcϵRI expression were noticeably reduced 7 days after initiating omalizumab treatment. These data corresponded with the onset of symptom relief, and basophilic activity remained suppressed throughout the omalizumab treatment period (30).

Our severe CSU patient responded similarly to omalizumab treatment (2). CRA1 antibody confirmed that the amount of FcϵRI expressed on basophils decreased, reflecting the result of IgE neutralization by omalizumab. CRA2 antibodies, which recognize the IgE–FcϵRI binding site, can measure unbound FcϵRI but did not detect any free FcϵRI on peripheral-blood basophils before omalizumab administration. These results mean that all the IgE receptors on peripheral-blood basophils are in a state of IgE binding. Flow cytometry confirmed that CRA2-positive basophils appeared only after external IgE was neutralized by omalizumab.

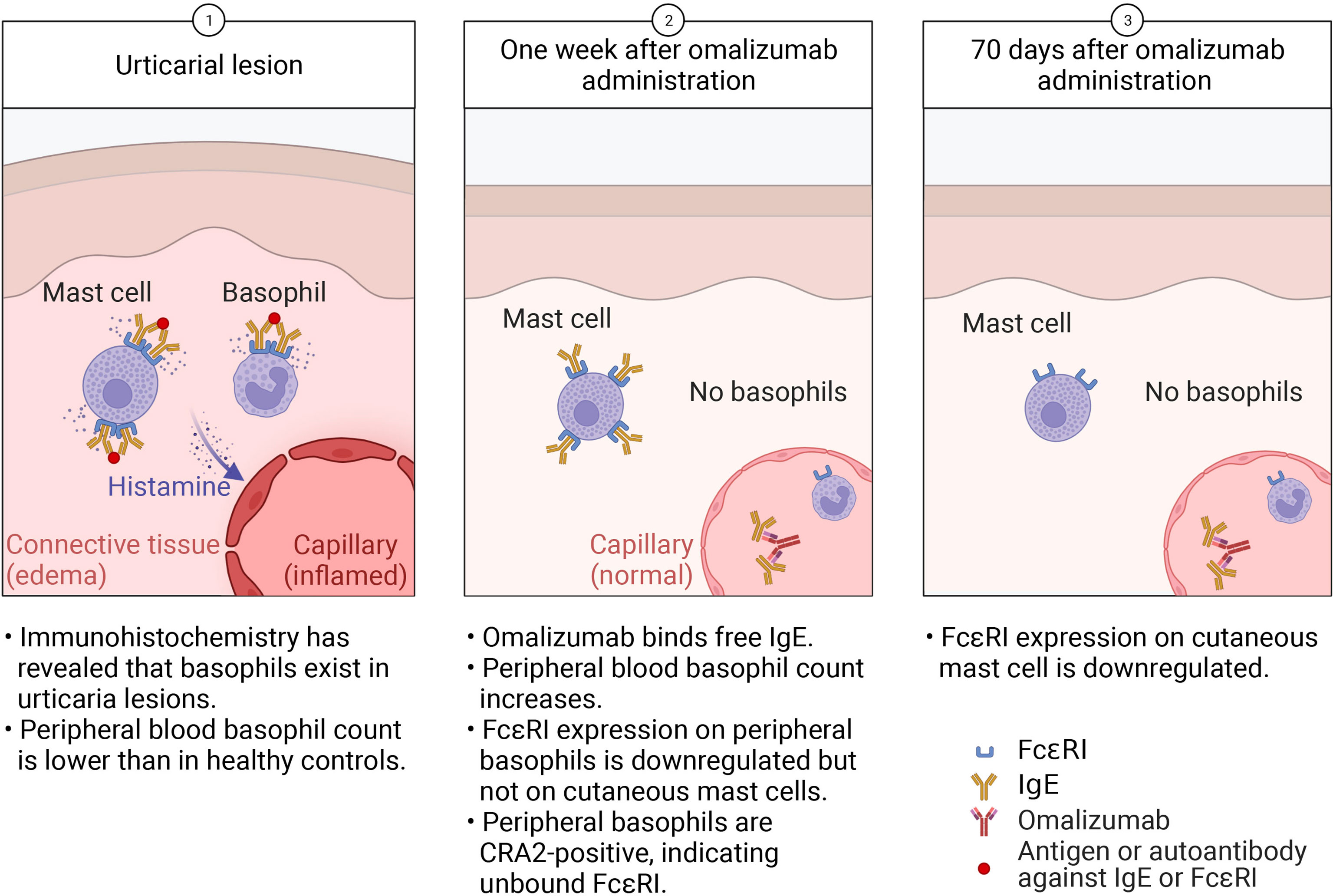

Interestingly, the reduction of FcϵRI expression on cutaneous mast cells is much slower than for basophils (Figure 2). A previous report indicated that it takes 70 days after omalizumab administration for mast-cell FcϵRI expression to be significantly reduced (29). The phenotypic change in cutaneous mast cells observed with omalizumab treatment offers novel insights into the time required for tissue responses and mast cell behavior to shift in CSU (16). The same is observed in cell cultures; when human mast cells, purified from the skin are cultured in vitro, the FcϵRI expression does not decrease even IgE has been withdrawn for 4 to 8 weeks (31). Unlike peripheral-blood basophils, once skin mast cells have acquired FcϵRI expression, its expression does not immediately change when external IgE levels decrease. This difference may be related to the lifespan length of the two cells. In basophils, further studies are needed to determine whether the amount of IgE receptors on the same cell can change depending on the amount of external IgE, or whether new cells are mobilized from the bone marrow each time, resulting only in expressing FcϵRI dependent on the amount of external IgE.

Figure 2 In urticaria, (Step 1) activated cutaneous mast cells and basophils release histamine, which acts on blood vessels to cause swelling. Activated basophils are recruited to the skin lesion, lowering the peripheral-blood basophil count. (Step 2) Within a week of omalizumab administration, the reduction in free IgE leads to decreased FcϵRI expression on basophils but not cutaneous mast cells. Activated, CD203c+ basophils stay in the peripheral blood. (Step 3) After 70 days of omalizumab treatment, mast-cell FcϵRI expression decreases but they remain in the skin.

Thus, that the early (within 7 days) onset of omalizumab’s therapeutic effects mirrors basophil dynamics and corresponds with changes in the basophil population leads us to hypothesize that basophils play a large role in CSU pathology (Figure 2). Although there is much to learn about urticaria, we expect that focusing on basophils will reveal new aspects of its pathogenesis.

Author Contributions

RT-I, IK, NM, KK and NK contributed to conception and design of the study. RT-I and NK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) to IK (Grant No. 20K17364).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted in collaboration with Professor H. Karasuyama and Dr. K. Miyake at the Tokyo Medical and Dental University. Figures were created with BioRender software, ©biorender.com.

References

1. Zuberbier T, Abdul Latiff AH, Abuzakouk M, Aquilina S, Asero R, Baker D, et al. The International EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI Guideline for the Definition, Classification, Diagnosis, and Management of Urticaria. Allergy (2022) 77(3):734–66. doi: 10.1111/all.15090

2. Kishimoto I, Kambe N, Ly NTM, Nguyen CTH, Okamoto H. Basophil Count Is a Sensitive Marker for Clinical Progression in a Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Patient Treated With Omalizumab. Allergol Int (2019) 68(3):388–90. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2019.02.002

3. Saini SS, Omachi TA, Trzaskoma B, Hulter HN, Rosen K, Sterba PM, et al. Effect of Omalizumab on Blood Basophil Counts in Patients With Chronic Idiopathic/Spontaneous Urticaria. J Invest Dermatol (2017) 137(4):958–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.025

4. Karasuyama H, Miyake K, Yoshikawa S, Yamanishi Y. Multifaceted Roles of Basophils in Health and Disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2018) 142(2):370–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.042

5. Yamanishi Y, Miyake K, Iki M, Tsutsui H, Karasuyama H. Recent Advances in Understanding Basophil-Mediated Th2 Immune Responses. Immunol Rev (2017) 278(1):237–45. doi: 10.1111/imr.12548

6. Johal KJ, Chichester KL, Oliver ET, Devine KC, Bieneman AP, Schroeder JT, et al. The Efficacy of Omalizumab Treatment in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Is Associated With Basophil Phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2021) 147(6):2271–80.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.02.038

7. Rijavec M, Kosnik M, Koren A, Kopac P, Selb J, Vantur R, et al. A Very Low Number of Circulating Basophils Is Predictive of a Poor Response to Omalizumab in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Allergy (2021) 76(4):1254–7. doi: 10.1111/all.14577

8. MacGlashan D Jr, Saini S, Schroeder JT. Response of Peripheral Blood Basophils in Subjects With Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria During Treatment With Omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2021) 147(6):2295–304.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.02.039

9. Fok JS, Kolkhir P, Church MK, Maurer M. Predictors of Treatment Response in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Allergy (2021) 76(10):2965–81. doi: 10.1111/all.14757

10. Alizadeh Aghdam M, Knol EF, van den Elzen M, den Hartog Jager C, van Os-Medendorp H, Knulst AC, et al. Response of FcepsilonRI-Bearing Leucocytes to Omalizumab in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy (2020) 50(3):364–71. doi: 10.1111/cea.13566

11. Huang AH, Chichester KL, Saini SS. Association of Basophil Parameters With Disease Severity and Duration in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria (CSU). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract (2020) 8(2):793–5.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.004

12. Grattan CE, Dawn G, Gibbs S, Francis DM. Blood Basophil Numbers in Chronic Ordinary Urticaria and Healthy Controls: Diurnal Variation, Influence of Loratadine and Prednisolone and Relationship to Disease Activity. Clin Exp Allergy (2003) 33(3):337–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01589.x

13. Buhring HJ, Seiffert M, Giesert C, Marxer A, Kanz L, Valent P, et al. The Basophil Activation Marker Defined by Antibody 97A6 Is Identical to the Ectonucleotide Pyrophosphatase/Phosphodiesterase 3. Blood (2001) 97(10):3303–5. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3303

14. Gentinetta T, Pecaric-Petkovic T, Wan D, Falcone FH, Dahinden CA, Pichler WJ, et al. Individual IL-3 Priming Is Crucial for Consistent In Vitro Activation of Donor Basophils in Patients With Chronic Urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2011) 128(6):1227–34.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.07.021

15. Kalm F, Mansouri L, Russom A, Lundahl J, Nopp A. Adhesion Molecule Cross-Linking and Cytokine Exposure Modulate IgE- and Non-IgE-Dependent Basophil Activation. Immunology (2021) 162(1):92–104. doi: 10.1111/imm.13268

16. Kaplan AP, Gimenez-Arnau AM, Saini SS. Mechanisms of Action That Contribute to Efficacy of Omalizumab in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Allergy (2017) 72(4):519–33. doi: 10.1111/all.13083

17. Macglashan DW Jr, Saini SS. Omalizumab Increases the Intrinsic Sensitivity of Human Basophils to IgE-Mediated Stimulation. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2013) 132(4):906–11.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.056

18. Zaidi AK, Saini SS, Macglashan DW Jr. Regulation of Syk Kinase and FcRbeta Expression in Human Basophils During Treatment With Omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2010) 125(4):902–8.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.996

19. MacGlashan DW Jr, Savage JH, Wood RA, Saini SS. Suppression of the Basophil Response to Allergen During Treatment With Omalizumab Is Dependent on 2 Competing Factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2012) 130(5):1130–5.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.038

20. Palacios T, Stillman L, Borish L, Lawrence M. Lack of Basophil CD203c-Upregulating Activity as an Immunological Marker to Predict Response to Treatment With Omalizumab in Patients With Symptomatic Chronic Urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract (2016) 4(3):529–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.11.025

21. Prussin C, Griffith DT, Boesel KM, Lin H, Foster B, Casale TB. Omalizumab Treatment Downregulates Dendritic Cell FcepsilonRI Expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2003) 112(6):1147–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.003

22. Ito Y, Satoh T, Takayama K, Miyagishi C, Walls AF, Yokozeki H. Basophil Recruitment and Activation in Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Allergy (2011) 66(8):1107–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02570.x

23. Caproni M, Giomi B, Volpi W, Melani L, Schincaglia E, Macchia D, et al. Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria: Infiltrating Cells and Related Cytokines in Autologous Serum-Induced Wheals. Clin Immunol (2005) 114(3):284–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.10.007

24. Ying S, Kikuchi Y, Meng Q, Kay AB, Kaplan AP. TH1/TH2 Cytokines and Inflammatory Cells in Skin Biopsy Specimens From Patients With Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria: Comparison With the Allergen-Induced Late-Phase Cutaneous Reaction. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2002) 109(4):694–700. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.123236

25. Rorsman H. Basopenia in Urticaria. Acta Allergol (1961) 16:185–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1961.tb02894.x

26. Yamaguchi M, Sayama K, Yano K, Lantz CS, Noben-Trauth N, Ra C, et al. IgE Enhances Fc Epsilon Receptor I Expression and IgE-Dependent Release of Histamine and Lipid Mediators From Human Umbilical Cord Blood-Derived Mast Cells: Synergistic Effect of IL-4 and IgE on Human Mast Cell Fc Epsilon Receptor I Expression and Mediator Release. J Immunol (1999) 162(9):5455–65.

27. Yamaguchi M, Lantz CS, Oettgen HC, Katona IM, Fleming T, Miyajima I, et al. IgE Enhances Mouse Mast Cell Fc(epsilon)RI Expression In Vitro and In Vivo: Evidence for a Novel Amplification Mechanism in IgE-Dependent Reactions. J Exp Med (1997) 185(4):663–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.663

28. MacGlashan DW Jr., Bochner BS, Adelman DC, Jardieu PM, Togias A, McKenzie-White J, et al. Down-Regulation of Fc(epsilon)RI Expression on Human Basophils During In Vivo Treatment of Atopic Patients With Anti-IgE Antibody. J Immunol (1997) 158(3):1438–45.

29. Beck LA, Marcotte GV, MacGlashan D, Togias A, Saini S. Omalizumab-Induced Reductions in Mast Cell Fce Psilon RI Expression and Function. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2004) 114(3):527–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.06.032

30. Metz M, Staubach P, Bauer A, Brehler R, Gericke J, Kangas M, et al. Clinical Efficacy of Omalizumab in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Is Associated With a Reduction of FcepsilonRI-Positive Cells in the Skin. Theranostics (2017) 7(5):1266–76. doi: 10.7150/thno.18304

Keywords: basophil, urticaria, mast cell, IgE, omalizumab

Citation: Takimoto-Ito R, Ma N, Kishimoto I, Kabashima K and Kambe N (2022) The Potential Role of Basophils in Urticaria. Front. Immunol. 13:883692. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.883692

Received: 25 February 2022; Accepted: 20 April 2022;

Published: 17 May 2022.

Edited by:

Satoshi Tanaka, Kyoto Pharmaceutical University, JapanReviewed by:

Bettina Wedi, Hannover Medical School, GermanyCopyright © 2022 Takimoto-Ito, Ma, Kishimoto, Kabashima and Kambe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Naotomo Kambe, nkambe@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp

Riko Takimoto-Ito

Riko Takimoto-Ito Ni Ma

Ni Ma Izumi Kishimoto

Izumi Kishimoto Kenji Kabashima

Kenji Kabashima Naotomo Kambe

Naotomo Kambe