Emotional education for sustainable development: a curriculum analysis of teacher training in Portugal and Spain

- Research Centre in Education and Psychology, University of Évora, Évora, Portugal

The challenges before us indicate that the current model of societal development is creating problems for our planet, such as the climate crisis, the increase in inequalities, and the emergence of new phenomena of exclusion and social malaise. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development presents 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that define priorities for a more sustainable world. Education is one of the main ways to create a peaceful and sustainable world for the survival and prosperity of present and future generations. The literature highlights the importance of teachers’ socio-emotional skills and the promotion of socio-emotional skills in their students. The Emotional Education approach proposes a new pedagogical paradigm, in which the individual is encouraged to develop intra-and interpersonal skills, enabling them to deal creatively with their conflicts and those encountered in the environment, and increasing their self-confidence and emotional balance. These skills will contribute to the achievement of the objectives of the SDG. Based on these arguments, the study and systematization of social–emotional education is urgent. In this study, a documentary analysis was carried out of the programs of study offered as part of the degrees (undergraduate and master’s level) provided for the training of preschool and primary teachers in Portugal and Spain, with the aim of understanding whether these courses offer content relating to Emotional Education. Programs of study from 127 public and private higher education institutions across both countries were analyzed. The analysis revealed that in Portugal, despite an increase in interest in issues relating to emotional intelligence in schools, this interest is not yet reflected in the initial training of preschool and primary teachers (with only two universities, both private institutions, offering Emotional Education content). In Spain, there is already a considerable number of institutions (29) that offer Emotional Education, but this corresponds to only 30% of the universities listed. The results of this study indicate that there is still some distance to go to make Emotional Education an effective component of the curricula of future teachers and thus contribute to achievement of the SDGs.

1. Introduction

The first decades of the 21st century have been characterized by several unexpected and challenging developments. The acceleration of technological and scientific advances, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the beginning of a war in Europe, and the issue of climate change are indicative of worsening conditions for millions of people, in both the physical and the mental domains. In this regard, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development emphasizes the value of an adequate educational response to the multiple challenges facing humanity. Therefore, all these issues have repercussions for discussions of the education system and the teaching profession (López-Cassá and Pérez-Escoda, 2020; Cristóvão, 2021). In particular, all these changes require that teachers have emotional skills that allow them to face the difficulties associated with these new contexts and to ensure the success of the teaching and learning process (Valente et al., 2022).

There is a global need to update educational systems to models that meet the current and future needs of children and young people, and that respond positively to the challenges of an uncertain future (Cristóvão, 2021). It is necessary to change the paradigm of education, promoting education for sustainable development, in which attention is paid to the holistic development of children and young people in terms of their well-being and their flourishing as human beings and to the cultivation of their qualities and virtues, taking integration and harmony as the main educational objectives (Kickbush, 2012). The current literature on the challenges of the 21st century is clear: citizens need tools to build fairer, more resilient, and sustainable societies. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is an important document that reflects the importance of an adequate educational response to the various challenges facing humanity.

A change in personal and social attitudes is therefore necessary to enable the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Several authors share the opinion that we cannot have respect for the natural environment and for the species living on the planet if we do not have respect for ourselves, for human beings, and for and society in the first place (Collado, 2016; García, 2022). In order to have respect for ourselves and others, it is necessary to develop our intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence. Intrapersonal intelligence is about introspecting, while interpersonal intelligence is about understanding others. Both intra-and interpersonal intelligence serve as a foundation for the development of the concept of emotional intelligence, which was proposed by Mayer and Salovey (1997). According to Mayer and Salovey (1997), emotional intelligence is one’s capacity to perceive, express, understand, use, and manage emotions in oneself (personal intelligence) and in others (social intelligence), which leads to adaptive behavior. Given the conceptualization of emotional intelligence as an individual skill, capable of development, education should promote its improvement and applicability for life, through the development of socio-emotional skills as an essential element of the curriculum. Socio-emotional competencies help people to recognize, process, and manage their own emotions and those of others (CASEL, 2012; Zych et al., 2018). Bisquerra (2000) proposes Emotional Education as an educational innovation with the aim of developing emotional competencies: emotional awareness, emotional regulation, interpersonal intelligence, life skills, and well-being.

In this article, we assume that the benefits of emotional education are important for achieving sustainable development. We reflect on the importance of universities in promoting the development of socio-emotional skills in future teachers and educators, in order to advance Education for Sustainable Development.

1.1. Social and emotional competencies

The concept of socio-emotional competencies has been developed and promoted in light of the results of research that has been carried out over the years on the impact of these skills on school success and on life (Elksnin and Elksnin, 2004; Weissberg et al., 2015). It was in the United States that this movement began and that the term Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) was initially used. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL, 2003) presents SEL as a promising approach to promoting student success in school and in life, with the goal of supporting students in dealing adequately with the demands of life in complex modern society. The aim of socio-emotional learning is to help students become fully functioning members of society, i.e., responsible adults with good work habits and with the ability to establish and maintain good social and family relationships and to be healthy, involved, interested, and loving people (Weissberg, and O‘Brien, M. U., 2004).

Social and emotional competencies can be promoted and developed through socio-emotional learning programs designed to promote social and emotional skills; these are implemented at the school level. CASEL recommends that SEL programs should have five key competencies as their direct targets: (1) competencies in self-awareness (the ability to understand one’s own emotions, personal goals, and values, which includes accurately assessing one’s strengths and limitations and possessing a well-grounded sense of confidence and optimism); (2) competencies in self-management (the ability to regulate emotions and behaviors); (3) competencies in social awareness (the ability to take on the perspectives of those from different cultures and backgrounds); (4) competencies in relationship skills (the ability to establish and maintain healthy and rewarding relationships); and (5) competencies in responsible decision-making (the ability to consider ethical standards, safety concerns, and accurate behavioral norms for risky behaviors, to realistically evaluate the consequences of various actions, and to take the health and well-being of oneself and others into consideration; CASEL, 2003). These five CASEL competencies reflect the intrapersonal and interpersonal domains (National Research Council, 2012). Self-awareness and self-management deal with issues in the intrapersonal domain, whereas social awareness and relationship skills are interpersonal. Responsible decision-making is both an individual and a social process and therefore overlaps with both domains (CASEL, 2012; Cristóvão et al., 2017).

The SEL approach contends that, as with academic skills, the development of social and emotional competencies must be accomplished through explicit instruction (Cristóvão et al., 2017). According to Weissberg et al. (2015), the most prevalent SEL approach “involves training teachers to deliver explicit lessons that teach social and emotional skills, then finding opportunities for students to reinforce their use throughout the day” (2015, p. 8). The development of competence occurs within and outside the classroom in school context, but also at the family, community, and political levels (Weissberg et al., 2015). Schonert-Reicht (2017) concludes that the success of SEL programs is directly related to teachers’ beliefs and their well-being. This underscores the importance of providing teacher training in SEL and explicitly promoting SEL in initial teacher training (Schonert-Reicht, 2017).

SEL has found support in other countries under other names: in England it is known as “Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning” (SEAL), in Canada as “Education for Responsibility,” and in Spain as “Emotional Education” (Bisquerra and López-Cassá, 2020). In this article we also use the term Emotional Education, which seems to us to be the most appropriate.

1.2. Emotional education for well-being

Emotional Education was developed in parallel with the growing interest of the scientific community in the study of positive emotions, emotional well-being, and positive psychology. This concept appeared in the mid-90s with the aim of responding to social needs that were not included in school curricula (Bisquerra and López-Cassá, 2020). Emotional Education is defined by Bisquerra (2000) as,

[…] a continuous and permanent educational process, which aims to promote emotional development as an essential complement to cognitive development, both constituting the essential elements of the development of the integral personality. For this, the development of knowledge and skills about emotions is proposed to train the individual to better face the challenges that arise in daily life. All of this is aimed at increasing personal and social well-being (p.243).

Emotional Education adopts contributions from various sciences, which are integrated into a unit of action; these concepts include emotional intelligence, positive psychology, neuroscience, and the theory of multiple intelligences (Bisquerra and López-Cassá, 2020). The authors emphasize the importance of Emotional Education, referring to the main purpose of education, namely the full development of the student’s integral personality. Two fundamental aspects of this form of development can be distinguished, namely cognitive development and personal development; “emotional, social and moral development, among others” are included in the latter (Bisquerra and López-Cassá, 2020, p.20). According to these authors, Emotional Education contributes to the development of emotional skills and to the creation of a positive emotional climate, which is beneficial to learning and well-being.

The issue of well-being is currently a fundamental one in education. The first decades of the 21st century showed us that our lives can change radically from one moment to the next, as was the case with the pandemic or the start of new wars. These events brought about consequences worldwide, especially in terms of mental health problems, such as anxiety, emotional exhaustion, and depression. As Pérez-Escoda and López-Cassá (2022) state, “it is necessary to recover well-being and take care of the physical and mental health of the citizenry, to foster its strengths and to invest decisively in teaching and developing healthy practices” (p.25). The authors state that the development of socio-emotional skills is the best way for people to overcome challenges and difficulties and to develop their well-being.

As a polysemous concept, well-being can be defined in different ways according to context. Bisquerra (2013) refers to various types of well-being: material, physical, social, professional, and emotional. The author mentions that material well-being, related to economic and technological development, is the prevalent meaning; however, there are many people with great economic capacity who are not happy. Physical well-being, in Bisquerra’s opinion, is very important, as it refers to physical health, bearing in mind that physical well-being does not mean merely the absence of illness. Social well-being, according to the author, is characterized by the maintenance of good relationships with people. Professional well-being relates to the occupation that fills most of our time, professional practice. Finally, emotional well-being, also referred to as subjective well-being, consists of experiencing positive emotions, which, for the author, is what comes closest to happiness. Bisquerra (2020) states that the purpose of education should be the development of global well-being, stressing that for each type of well-being there are educational strategies that contribute to its development.

1.3. Contributions of emotional education to sustainable development

On 1 January 2016, a United Nations resolution entitled “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” came into force. This agenda consists of 17 goals, broken down into 169 associated targets, and was approved by world leaders in 2015. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to address the needs of people in both developed and developing countries by 2030, emphasizing the idea that no one should be left behind. For this article, we highlight Goal 3 (“Good health and well-being: ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages,” which, among other targets, includes the aim of promoting mental health and welfare) and Goal 4 “Quality education: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all,” which, among other targets, includes the aim of ensuring that all students acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to promote sustainable development “through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development” (UNRIC, 2018).

UNESCO has been the lead agency of the United Nations in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). ESD is widely recognized as an integral element of the 2030 Agenda, in particular Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), and a key enabler of all other Sustainable Development Goals.

According to UNESCO (2020),

To shift to a sustainable future, we need to rethink what, where and how we learn to develop the knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes that enable us all to make informed decisions and take individual and collective action on local, national and global urgencies (p.8).

ESD is defined as a continuous learning process and an integral component of quality education that reinforces the cognitive, social, emotional, and behavioral dimensions of learning. ESD is a holistic and transformative process that encompasses learning content and outcomes, pedagogy, and the learning environment itself (UNESCO, 2020). According to this report, the fundamental changes needed for a sustainable future start with individuals. ESD places emphasis on how each student undertakes transformative actions for sustainability, including the importance of opportunities to expose students to reality, and how they influence the transformation of society toward a sustainable future.

According to UNESCO (2020), in order to achieve the goals of sustainable development, it is necessary to develop key skills for sustainability, such as anticipatory skills, collaboration, self-awareness, and problem-solving. Regarding specific sub-goal targets, it is necessary to develop skills in three domains: the cognitive domain, the socio-emotional domain, and the behavioral domain. Achieving the SDGs will require national governments to integrate these skills into their education policies and frameworks. It is also necessary to give educators the opportunity to develop their own capacity to move society toward a sustainable future. UNESCO suggests that the teaching staff of educational institutions should include the systematic and comprehensive development of ESD skills in pre-service and in-service training and in the evaluation of teachers working in pre-primary, primary, secondary, and tertiary education, including primary, secondary, and continuing education of adults. This should include SDG-specific learning content, as well as transformative pedagogies for social action.

One of the dimensions of Education for Sustainable Development is the social and emotional dimension of learning, which aims to build fundamental values and attitudes for sustainability, to cultivate empathy and compassion for others and the planet, and to instill motivation to lead change (UNESCO, 2020). Regarding the relationship between Emotional Education and sustainable development, García (2022) states that we cannot respect the environment if we do not respect ourselves as human beings. It is in this context that the author refers to the importance of developing emotional intelligence through Emotional Education, concluding that “emotional intelligence is a fundamental dimension of learning to feel-think-act in sustainable harmony with ecosystems” (p.41).

1.4. The importance of emotional education in teacher training

Mayer and Salovey’s (1997) model conceptualizes emotional intelligence as a competence that can be learned and developed and that consists of the adaptive use of emotional information. In turn, emotional competencies are understood as a set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to emotional awareness, emotional regulation, emotional autonomy, social competence, and life and well-being skills (Alzina and Andrés, 2019). These authors also indicate that emotional intelligence is among the foundational concepts underlying emotional competencies, and that Emotional Education is an educational process that aims to develop emotional competencies. Thus, emotional intelligence is one of the foundations of emotional competencies, and Emotional Education is the process by which they are developed (Alzina and Andrés, 2019; Valente et al., 2022).

A study by the World Economic Forum (2016) indicates that two in every three future professions do not exist yet, and although the study does not indicate which professions will be the most promising, it concludes that professional success is highly dependent on interpersonal relationship skills linked to the emotional basis of individuals. In addition, the findings also indicate that skills such as emotional intelligence and negotiation will have a greater impact than training in scientific and technical skills. Thus, emotional intelligence is one predictor of success in the academic and professional field (Dolev and Leshem, 2017), and provides individuals with the ability to cope with and handle the complex, stressful, and changing situations encountered in today’s world (Hadar et al., 2020). In the field of education, emotional intelligence has been found to be positively associated with various characteristics of teachers, such as personal well-being (Kant and Shanker, 2021), professional performance (Wahyuddin, 2016), quality of relationships with students (Gill and Sankulkar, 2017), and skills in managing conflict in the classroom (Valente and Lourenço, 2020), as well as the academic performance of their students (Wang, 2022).

Emotional competencies are fundamental in allowing human beings to adapt to the ecosystems in which they find themselves (Bisquerra and Pérez, 2007). Therefore, teaching is a demanding undertaking, and emotional relationships are evident in all classrooms (Valente et al., 2022), where relationships can act as a source of positive development (Xie and Derakhshan, 2021), as well as causing emotional exhaustion for teachers and students (Valente and Lourenço, 2020). For example, disobedience, confrontations with students, problems with the school system, and loss of authority can push teachers to the limits of their cognitive and emotional resilience (Valente and Almeida, 2020).

Given the key role that emotional intelligence can play in an individual’s well-being (Ju et al., 2015; Mérida-López and Extremera, 2020) and professional success (Wahyuddin, 2016), the development of teachers’ emotional competence within the education system has gained importance in recent years (Arteaga-Cedeño et al., 2022). However, in Portugal, academic curricula in teacher training still seem too distant from reality, often resorting to watertight curriculum planning and canonical manuals (Valente and Almeida, 2020). Additionally, Jesus (2002) carried out an analysis of the curricula of several Portuguese institutions and concluded that the classical training provided to Portuguese teachers is restrictive in terms of, or at least does not stimulate, the affective component. Similarly, Nóvoa (2017) argues that current models of teacher training are outdated and it is necessary to rethink their renewal, particularly in relation to teachers’ relationships with students. According to Valente and Almeida (2020), as a rule, the training offered during Portuguese teacher training is still overly guided by purely scientific objectives and based in knowledge to an excessive extent, often prioritizing exclusively the analysis and reproduction of scientific knowledge. In this sense, it is important to develop training opportunities for emotional competencies to ensure more integral development of teachers (Extremera et al., 2020; Valente and Lourenço, 2022). Conditions must be created to prepare teachers for the continuous and unpredictable changes that characterize the education system in response to the demands of society (Valente and Almeida, 2020).

One evaluation of an Emotional Education program aimed at primary school teachers, carried out in Spain, shows a significant improvement in the emotional competence of the participants at the end of the program and suggests that it is effective in promoting the development of teachers’ emotional competence, as well as in improving the institutional climate (Escoda et al., 2013). Additionally, the results of a short program on emotional intelligence in the initial training of education professionals (examined in a pilot study in which the program was delivered to a group of 15 students as part of the Master’s Degree in Secondary Education at the University of Malaga) suggest that the students considered the learning and teaching of socio-emotional tools to have helped them to cope with daily teaching stressors and that they found these tools very useful in the short term and highly applicable for their professional careers in the long term (Extremera et al., 2020). In Portugal, Amaral (2013) mentions that after the implementation of “the emotional dimension in a teacher development training program,” changes occurred in the participants’ ability to identify and discriminate between emotions. Changes were also observed in teachers’ levels of collaboration, in their assumptions about the importance of emotional literacy in increasing resilience, in their professional autonomy, and in their emotional well-being.

Various programs have confirmed the relevance of teachers’ emotional intelligence, demonstrating that it is possible to develop emotional competencies in adulthood and that learning continues into teachers’ professional lives (e.g., Kotsou et al., 2011; Nélis et al., 2011; Moghanlou et al., 2016). Based on this approach, if future teachers are exposed to Emotional Education training as part of their higher education, they will develop competencies that will allow them, in their future professional lives, to manage the factors that cause personal stress and to increase their efficacy in their professional roles (Valente and Almeida, 2020). Therefore, emotional competencies should be integrated into initial teacher training curricula and these curricula should offer specific content targeting the development of these competencies (Costa et al., 2021; Valente et al., 2022).

It should be noted that several national and international studies have point to the need for training programs in the field of Emotional Education as part of initial teacher training courses (e.g., Ju et al., 2015; Cristóvão et al., 2020; Mérida-López and Extremera, 2020; Valente and Lourenço, 2020; Arteaga-Cedeño et al., 2022; Sauli et al., 2022; Valente, 2022). In this sense, this article focuses on the benefits of Emotional Education in achieving the goals of sustainable development. We reflect on the importance of universities promoting the development of emotional competencies in future educators and teachers, in order to promote education for sustainable development.

2. Methods

The study adopted a descriptive (comprehensive) qualitative approach, quantification of the occurrences of curricular units with emotional education contents. As Vilelas (2017) points out, this type of study “seeks to know the characteristics of a given population/phenomenon” (p.178), i.e., it describes a specific aspect of reality, and the objective is to demonstrate a phenomenon. We opted for an exploratory approach that could provide us with initial data that would allow us to understand whether teacher training courses currently provided in Portugal and Spain offer their trainees curricular units on Emotional Education.

Data analysis was performed in two stages. First, it was necessary to conduct a survey of the public and private universities in Portugal and Spain that train primary and preschool teachers. To collect the data for Portugal, we consulted the website of the Directorate-General for Higher Education, https://www.dges.gov.pt/guias/indcurso.asp?curso=9853. In Spain, the list of universities published on the website https://www.educacion.gob.es was consulted. It should be stated that these webpages are official sources from the Ministry of Education of the governments of the respective countries. This approach ensured that we would have access to the full list of institutions.

Second, we analyzed the official program of study for each of the teacher training programs, implemented in 2022/2023, which were available on each university’s website. These programs of study are evaluated and approved by public agencies in each country: in Portugal by the Agency for Assessment and Accreditation of Higher Education (A3ES), and in Spain by the National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (ANECA). Using these two sources of information, it was possible to validate the information obtained.

This analysis of programs of study for primary education and preschool teachers was carried out by considering curricular units that addressed the following topics falling under Emotional Education: emotional awareness, emotional regulation, emotional autonomy, social skills, and skills for life and well-being.

3. Results

The results obtained from data collection are presented in tables to facilitate reading and interpretation. The training of preschool and primary teachers is organized differently in Portugal and Spain. In Portugal, this training is divided into two phases: the first (3 years) consists of a degree in Basic Education, aimed at all those who wish to study to become preschool or/and primary teachers; the second (2 years) is a master’s degree conferring professional qualification for teaching in preschool and primary school. In Spain, the training of primary teachers and preschool teachers lasts 4 years. Table 1 presents an overview of the universities that were included in our analysis, across both countries.

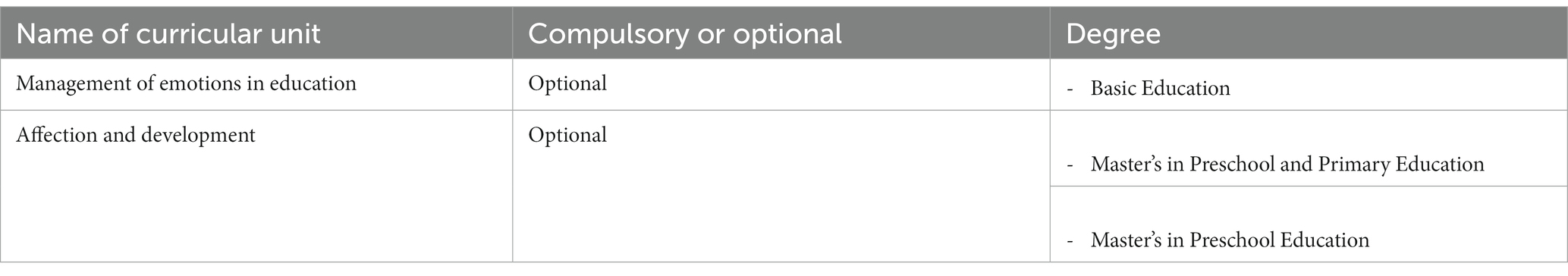

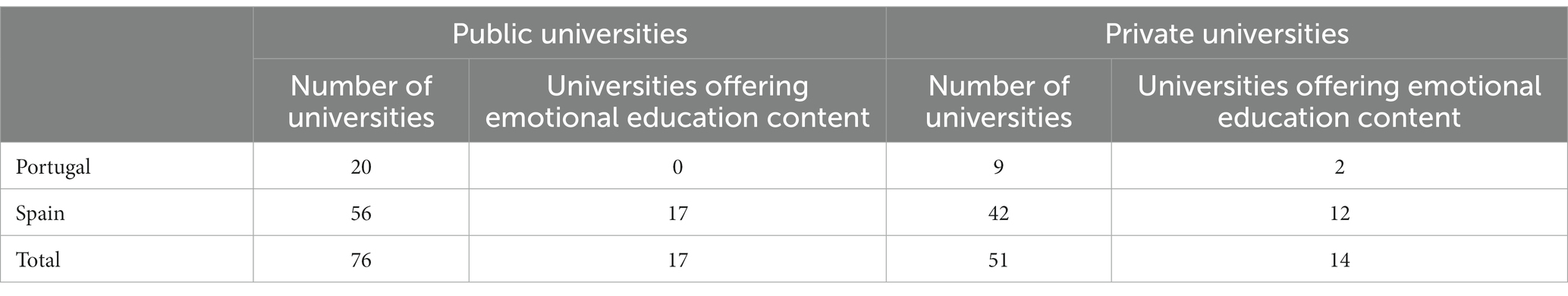

Table 1. Public and private universities in Portugal and Spain offering primary and preschool teacher training programs and emotional education content.

As indicated in Table 1, we identified 127 universities where training courses for primary and preschool teachers were available. In Portugal, courses offered by a total of 29 universities were analyzed, of which 20 were public universities and 9 private. Analysis of the courses offered in the training programs for preschool and primary teachers showed that only the two private universities offered curricular units with Emotional Education content. In Spain, 98 universities offered these teacher training programs, of which 56 were public universities (17 providing curricular units with Emotional Education content) and 42 were private universities (12 providing curricular units with Emotional Education content). Table 2 presents the name of the curricular units with emotional education content, their compulsory or optional nature, and the level of study at which these curricular units were offered.

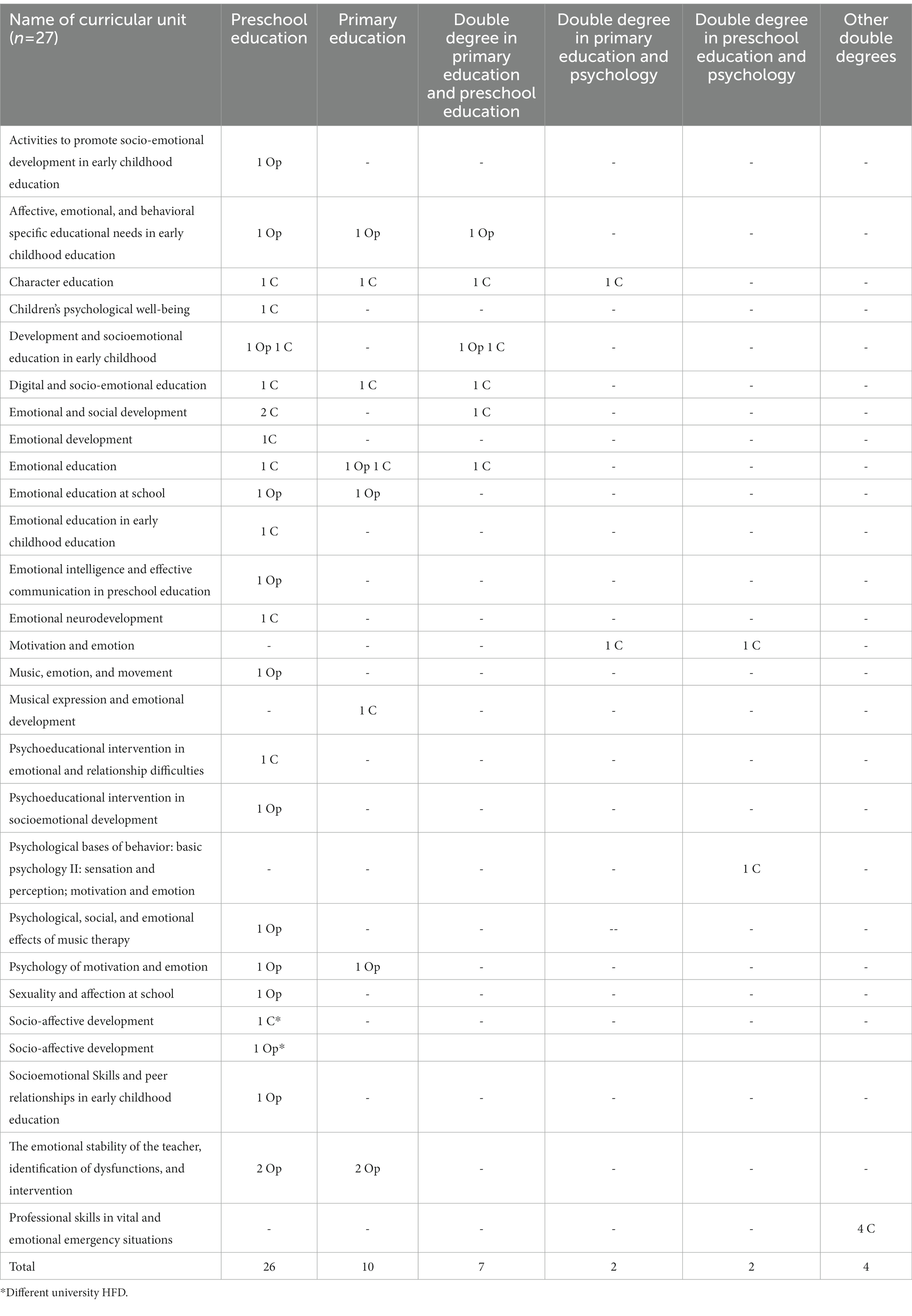

In Portugal, the two curricular units with emotional education content were offered to students as optional units. “Management of Emotions in Education” was offered as part of the Basic Education degree, and “Affection and Development” was offered as part of two master’s degrees. Table 3 presents the curricular units with Emotional Education content and the degrees that offer these units in Spain.

Spanish universities offered 27 different curricular units with Emotional Education content, which consisted of 51 modules distributed over six different types of degree: degrees in Preschool Education (26), degrees in Primary Education (10), double degrees in Primary Education and Preschool Education (7), double degrees in Primary Education and Psychology (2), double degrees in Preschool Education and Psychology (2), and other double degrees (2). Of these modules, 22 were optional and 29 were compulsory.

4. Discussion

A quality education should provide a solid basis of knowledge, but must also provide for good cognitive (intellectual and affective) and motor development. In this article, we begin from the structural idea that teachers and educators are agents specifically tasked with providing children and young people with the tools and techniques necessary to acquire social and emotional competencies, especially in a post-pandemic context. In order to be able to provide these tools, future teachers must naturally have acquired them for themselves.

Emotional Education can be a very useful tool in the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. Goals such as “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” and “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” fit perfectly into the concept of learning for well-being (Kickbush, 2012). Emotional Education is based on a new pedagogical paradigm which states that all individuals should develop intra-and interpersonal skills, know how to creatively deal with their own conflicts and those in the environment, and increase their self-confidence and emotional balance.

The results show that Emotional Education appears in the academic curricula of training programs for teachers and educators in association with a variety of areas of knowledge across the spectrum of human development, with particular focus on psychology, sociology, and neuroscience. In Portugal, only two private universities offer courses in Emotional Education (“Management of Emotions in Education” and “Affection and Development”), both optional. In Spain, there are already 29 universities (30% of the total) offering 27 different curricular units with content relating to Emotional Education, divided into 51 modules (22 compulsory and 29 optional).

There is still some distance to go to make Emotional Education an effective component of the curricula provided for the development of future teachers and educators. It is important to train professionals who are more aware of and prepared to deal with the social and emotional development of their students and to better equipped to contribute to their well-being and to the provision of a quality education adjusted to the challenges of this century, fully in line with the Sustainable Development Goals. Achievement of the future that societies want will depend to a large extent on how we are training our students, the content that is taught, and the ways in which we relate to and respect one another. Thus, contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals also implies investing in teacher training, with the development of curricula that are more concerned with people and their well-being.

5. Conclusion

This article presents an initial exploratory investigation that sought to understand whether teacher training courses are integrating the teaching of Emotional Education competencies in their curricula, because of the importance of this in the fulfillment of the SDGs.

Despite a very solid scientific basis for this area and growing interest from academics and non-academics, this interest is not yet reflected in the courses of study provided as part of the initial training of preschool teachers and primary teachers. Both countries need to improve, but in comparison to Spain, Portugal has further to go in fully incorporating this type of content into course curricula.

Further investigation would, of course, be required to understand the reasons why it has been so difficult for Emotional Education to be integrated into academic curricula, especially teacher training curricula. With the relevant curricular units having being identified, future research will also be necessary to analyze in greater detail the content delivered under the different subjects.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.dges.gov.pt./guias/indcurso.asp?curso=9853 and https://www.educacion.gob.es.

Author contributions

AC designed the study, carried out statistical data analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AR organized the database. SV and HR wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was financed by national funds from the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), I.P., within the scope of the project UIDB/04312/2020.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alzina, R. B., and Andrés, J. M. (2019). Competencias emocionales para un cambio de paradigma en educación. Barcelona: Horsori Editorial, S. L.

Amaral, A. M. (2013). A dimensão emocional no desenvolvimento do professor. [Tese de Doutoramento, Instituto de Educação, Universidade de Lisboa]. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/8040

Arteaga-Cedeño, W. L., Carbonero-Martín, M. Á., Martín-Antón, L. J., and Molinero-González, P. (2022). The sociodemographic-professional profile and emotional intelligence in infant and primary education teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:9882. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19169882

Bisquerra, R., and López-Cassá, E. (2020). Educación Emocional: 50 perguntas y respuestas. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires: El Ateneo.

Bisquerra, R., and Pérez, N. (2007). Las competencias emocionales. Educación XXI Revista de la Facultad de Educación 10, 61–82. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.1.10.297

CASEL. (2003). An educational leader’s guide to evidence-based social and emotional learning (SEL) programs. IL: Chicago.

CASEL. (2012). CASEL guide: Effective social and emotional learning programs-preschool and elementary school edition. IL: CASEL.

Collado, J. (2016). Educación emocional: retos para alcanzar un desarrollo sostenible. Revista arbitrada del centro de investigación y estúdios gerenciales 26, 27–46.

Costa, C., Palma, X., and Salgado, C. (2021). Docentes emocionalmente inteligentes. importancia de la inteligencia emocional para la aplicación de la educación emocional en la práctica pedagógica de aula. Estud. Pedagog. 47, 219–233. doi: 10.4067/S0718-07052021000100219

Cristóvão, A. M. (2021). Dinâmicas inovadoras e promotoras de ambientes de Aprendizagem para o Bem-Estar: o caso das Comunidades Escolares de Aprendizagem Gulbenkian XXI. [Tese de Doutoramento não publicada]. Évora: Universidade de Évora.

Cristóvão, A. M., Candeias, A. A., and Verdasca, J. (2017). Social and emotional learning and academic achievement in Portuguese schools: A Bibliometric study. Front. Psychol. 8:1913. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01913

Cristóvão, A. M., Candeias, A. A., and Verdasca, J. L. (2020). Development of socio-emotional and creative skills in primary education: teachers’ perceptions about the Gulbenkian XXI school learning communities project. Front. Educ. 4:160. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00160

Dolev, N., and Leshem, S. (2017). Developing emotional intelligence competence among teachers. Teach. Dev. 21, 21–39. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2016.207093

Elksnin, L. K., and Elksnin, N. (2004). The social-emotional side of learning disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Q. 27, 3–8. doi: 10.2307/1593627

Escoda, N. P., Guiu, G. F., Benet, A., and Fondevila, A. (2013). Evaluación de un programa de educación emocional para profesorado de primaria. Educación XX1 16, 233–254. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.16.1.725

Extremera, N., Mérida-López, S., Rey, L., and Peláez-Fernández, M. A. (2020). “Diseño de un programa breve de inteligencia emocional para la formación inicial de profesionales de la educación” in Avances en Ciencias de la Educación: Investigación y Práctica. ed. M. P. Bermúdez (Madrid: Editorial DYKINSON), 48–54.

García, C. (2022). “Ecoeduemoción. Educación emocional y medio ambiente” in Retos para el bienestar social y emocional. eds. N. Pérez-Escoda and È. López-Cassà (Madrid: Cuadernos de Pedagogía), 37–54.

Gill, G. S., and Sankulkar, S. (2017). An exploration of emotional intelligence in teaching: comparison between practitioners from the United Kingdom & India. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry 7, 1–6. doi: 10.15406/jpcpy.2017.07.00430

Hadar, L. L., Ergas, O., Alpert, B., and Ariav, T. (2020). Rethinking teacher education in a VUCA world: student teachers’ social-emotional competencies during the Covid-19 crisis. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 573–586. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1807513

Jesus, S. N. (2002). Perspetivas Para o bem-estar docente: Uma lição de síntese. [perspectives for teacher well-being: A synthesis lesson]. Porto: Edições Asa.

Ju, C., Lan, J., Li, Y., Feng, W., and You, X. (2015). The mediating role of workplace social support on the relationship between trait emotional intelligence and teacher burnout. Teach. Teach. Educ. 51, 58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.06.001

Kant, R., and Shanker, A. (2021). Relationship between emotional intelligence and burnout: an empirical investigation of teacher educators. Int J Eval Res Educ 10, 966–975. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v10i3.21255

Kickbush, I. (2012). Learning for well-being: A policy priority for children and youth in Europe. A process for change. Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Kotsou, I., Nélis, D., Grégoire, J., and Mikolajczak, M. (2011). Emotional plasticity: conditions and effects of improving emotional competence in adulthood. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 827–839. doi: 10.1037/a0023047

López-Cassá, E., and Pérez-Escoda, N. (2020). La influencia de las emociones en la educación ante la COVID-19:El caso de España desde la percepción del professorado Universidad de Barcelona. Barcelona: GROP.

Mayer, J. D., and Salovey, P. (1997). “What is emotional intelligence?” in Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications. eds. P. Salovey and D. J. Sluyter (New York: NY. Basic Books), 3–31.

Mérida-López, S., and Extremera, N. (2020). The interplay of emotional intelligence abilities and work engagement on job and life satisfaction: which emotional abilities matter most for secondary school teachers? Front. Psychol. 11:563634. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.563634

Moghanlou, S. D., Sadeghian, A., Mehri, S., Razzaghi, I., and Molavi, P. (2016). Relationship between emotional intelligence and mental health with job stress among teachers. J Health Care 17, 300–310.

National Research Council (2012). Education for life and work: Developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nélis, D., Kotsou, I., Quoidbach, J., Hansenne, M., Weytens, F., and Dupuis, P. (2011). Increasing emotional competence improves psychological and physical well-being, social relationships, and employability. Emotion 11, 354–366. doi: 10.1037/a0021554

Nóvoa, A. (2017). “Repensar a formação de professores” in Atas do II Encontro Internacional de Formação na Docência (INCTE 2017). eds. M. Pires, C. Mesquita, R. Lopes, G. Santos, M. Cardoso, J. Sousa, E. Silva, and C. Teixeira (Bragança: Instituto Politécnico de Bragança).

Pérez-Escoda, N., and López-Cassá, E. (2022). “La educación emocional: una necessiad para el bienestar personal y social” in Retos para el bienestar social y emocional: La educación emocional más allá de las aulas. eds. I. N. Pérez-Escoda and E. López-Cassá (Madrid: Cuadernos de Pedagogía), 23–35.

Sauli, F., Wenger, M., and Fiori, M. (2022). Emotional competences in vocational education and training: state of the art and guidelines for interventions. Empir. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 14:4. doi: 10.1186/s40461-022-00132-8

Schonert-Reicht, K. (2017). Social and emotional learning and teachers. Fut Children 27, 137–155. doi: 10.1353/foc.2017.0007

UNESCO (2020). Educación para el Desarrollo Sostenible: Hojas de ruta. Francia: Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura.

UNRIC (2018). Guia sobre Desenvolvimento Sustentável: 17 Objetivos para Transformar o nosso Mundo. Lisboa: Centro de Informação Regional das Nações Unidas para a Europa Ocidental.

Valente, S. N. (2022). Development of emotional intelligence in pre-service teachers to increase professional well-being. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 18:555988. doi: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2022.18.555988

Valente, S., and Almeida, L. S. (2020). Educação emocional no Ensino Superior: Alguns elementos de reflexão sobre a sua pertinência na capacitação de futuros professores. Revista E-Psi 9, 152–164.

Valente, S., and Lourenço, A. A. (2020). Conflict in the classroom: how teachers’ emotional intelligence influences conflict management. Front Educ 5, 1–10. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00005

Valente, S., and Lourenço, A. A. (2022). Editorial: the importance of academic training in emotional intelligence for teachers. Front Educ. 7:992698. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.992698

Valente, S. N., Lourenço, A. A., and Dominguez-Lara, S. (2022). “Teachers in the 21st century: emotional intelligence skills make the difference” in Pedagogy-challenges, recent advances, new perspectives, and applications. ed. H. Şenol (IntechOpen). doi: 10.5772/intechopen.103082

Wahyuddin, W. (2016). The relationship between of teacher competence, emotional intelligence and teacher performance madrasah Tsanawiyah at district of Serang Banten. High. Educ. Stud. 6, 128–135. doi: 10.5539/hes.v6n1p128

Wang, L. (2022). Exploring the relationship among teacher emotional intelligence, work engagement, teacher self-efficacy, and student academic achievement: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 12:810559. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.810559

Weissberg, R., Durlak, J., Domitrovich, C., and Gullotta, T. (2015). “Social and emotional learning: past, present, and future” in Handbook of social and emotional learning. eds. J. Durlak, C. Domitrovich, R. Weissberg, and T. Gullotta (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 3–19.

Weissberg, R. P., and O’Brien, M. U. (2004). What works in school-based social and emotional learning programs for positive youth development. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 591, 86–97. doi: 10.1177/0002716203260093

World Economic Forum (2016). Employment, skills and workforce strategy for the fourth industrial revolution. Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs.

Xie, F., and Derakhshan, A. (2021). A conceptual review of positive teacher interpersonal communication behaviors in the instructional context. Front. Psychol. 12:708490. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708490

Keywords: emotional education, sustainable development goals, curricular analysis, primary teachers, preschool teacher

Citation: Cristóvão AM, Valente S, Rebelo H and Ruivo AF (2023) Emotional education for sustainable development: a curriculum analysis of teacher training in Portugal and Spain. Front. Educ. 8:1165319. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1165319

Edited by:

José Beltrán Llavador, University of Valencia, SpainReviewed by:

Nicolás Ponce-Díaz, University of Antofagasta, ChilePablo Caamus, University of Antofagasta, Chile

Maria Eulina Pessoa De Carvalho, Federal University of Paraíba, Brazil

Copyright © 2023 Cristóvão, Valente, Rebelo and Ruivo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ana Maria Cristóvão, alc@uevora.pt

Ana Maria Cristóvão

Ana Maria Cristóvão Sabina Valente

Sabina Valente Hugo Rebelo

Hugo Rebelo Ana Francisca Ruivo

Ana Francisca Ruivo