Internet Memes: Leaflet Propaganda of the Digital Age

- University of Maryland Global Campus, Adelphi, MD, United States

Internet memes are one of the latest evolutions of “leaflet” propaganda and an effective tool in the arsenal of digital persuasion. In the past such items were dropped from planes, now they find their way into social media across multiple platforms and their territory is global. Internet memes can be used to target specific groups to help build and solidify tribal bonds. Due to the ease of creation, and their ability to constantly reaffirm axiomatic tribal ideas, they have become an adroit tool allowing for mass influence across international borders. This text explores the link between internet memes and their ability to “hack” the attention of anyone connected to internet using dense modality and cognitive biases. Furthermore, the text discusses Internet meme's ability sew discord by consistently reaffirming preexisting tribal bonds and their relation to traditional PSYOP tactics initially used for analog leaflet propaganda.

Methodology

Through the use of media archeology this article aims to illuminate the evolution of analog leaflet propaganda into its contemporary digital form of internet memes. Through the use of macroscopic comparison and microscopic analysis a trend of parallel persuasion techniques can be observed between analog leaflet propaganda and internet memes.

Introduction

This article focuses on analog leaflet propaganda and modern digital internet memes in regards to their composition, dissemination, and application among their respective target audiences. Through the use of macroscopic comparisons a trend of parallel persuasion techniques can be observed between analog leaflet propaganda and internet memes. The article further highlights the parallel uses of both mediums in relation to their ability to utilize psychological tactics to disseminate information on a macroscopic level while simultaneously targeting a microscopic audience. Currently, aerial leaflet propaganda and internet memes are both in use in their respective theaters (the real-world and the digital-world). The use of aerial leaflet propaganda historically and the parallel usage of aerial leaflet propaganda and digital memes contemporarily offers a unique opportunity to explore their previously overlooked entanglements. Through excavating historical uses of aerial leaflet propaganda and their respective PSYOP tactics a more comprehensive analysis of internet memes and their role in digital manipulation becomes possible. This article is meant as a theoretical analysis of internet memes, and their propagandist properties, so that other researchers may bring forth empirical examples. The article follows a road map beginning with the historical aerial leaflet propaganda tactics, strategies, and goals highlighting the importance of targeted audiences. The focus of the article then shifts to a microscopic view of what internet memes are, and their innate faculties that allow for enhanced malleability and dispersal (including heuristic properties). The final portions of this article shine a spotlight on internet memes at work in the real world and future research opportunities stemming from this body of research.

Thought Bombs Raining Down From Above

Targeted audiences and strategically targeted objectives have been the foundation for which effective propaganda based information dissemination has developed. Every mass propaganda campaign needs a mechanism of conveyance to reach its target audience. For over a century engines have thundered across the skies around the globe with the sole purpose of being the mechanism of conveyance for propaganda based information dissemination. Leaflet propaganda is traditionally, “disseminated by hand, trash bag, leaflet box, and leaflet bomb, depending on the aircraft type and tactical situation” (US Army, 2003, k-10). In advance of the United States (hereafter US) led World War II invasion of Okinawa, Japan (1945) about six million aerial leaflets were dropped (Schmulowitz and Luckmann, 1945, p. 485). During the US's involvement in the Korean War (1950–53) US and United Nations forces scattered ~2.5 billion leaflets (over two million leaflets a day) on their targeted audiences, the Chinese forces, North Korean forces, and civilians (Kim and Haley, 2018). Each piece of paper was a key hoping to unlock a new way of viewing the conflicts at hand; As Schmulowitz and Luckman wrote, the aerial leaflets were essentially “thought bombs” (Schmulowitz and Luckmann, 1945, p. 428). These leaflets came in curious forms some of which were humorous, some informative, and others downright terrifying. Before moving onto how these same principles have evolved into their modern digital iteration it is best to take a macroscopic jaunt through the PSYOP driven tactics and strategies of analog leaflet propaganda in isolation before zooming in and intertwining them with their latest digitally driven iterations (internet memes) for a clearer picture of their parallel properties. The following example focuses on the aforementioned Okinawan and Korean conflicts. These were chosen among many other examples due to the depth of mass propaganda-focused scholarship available and the strict modal and cultural limitations of the propaganda in play in each theater (a significant point highlighted later in this article).

In both the Okinawan and Korean conflicts aerial leaflet propaganda focused on two categories of dissemination (target audiences): Those that were tactical and those that were strategic (Schmulowitz and Luckmann, 1945, p. 428). According to the work of Schmulowitz and Luckmann (1945, p. 428), the tactical target audience was primarily geared toward lowering the morale of enemy combatants often via delegitimization of their leaders, cause, or tactical situation. In conjunction with the tactical target audience leaflet propaganda would simultaneously bombard the Strategic target audience comprised of civilians: the goal being to persuade them into acting in ways helpful (directly and indirectly) to the allied military operations (p. 428). Propaganda would rain down in the forms of posters (similar to the macro-image memes discussed later), newspapers (Ryukyu Shuho/Rakkasan News), comics, and photos among others (Schmulowitz and Luckmann, 1945, p. 429). The same audiences were targeted in the Korean War with, “millions of messages directed at friend and foe” in which both civilians and enemy combatants were targeted with specific goals in mind (Psychological Warfare in Korea, 1951, p. 65–67; Kim and Haley, 2018). The propaganda distinguished between each category of specific targeting hoping to alter the thoughts and actions of the targeted audiences. The persuasive tactics fit broadly into four key areas of targeting.

The four key areas exploited to attempt to persuade their target audiences were as follows: ideology appeal, personal gratification appeal, communal values-focused appeal, and information dissemination (Kim and Haley, 2018). The four categories of persuasion created boundaries and allowed propagandists to generate tailor-made propaganda for their target audiences. The importance of using rhetoric and visual modalities to reach tribal based targeted audiences is vital to the success of such propaganda operations. In the Okinawa theater these categories set targeted intentionality over broad range of connected ideas through crediting or discrediting military and social figures. For example, the emperor, military cliques, the Yamato spirit, Japanese military leadership, the burden of civilians, among others were selected as key targets in [de]legitimizing the role of both state actors (Schmulowitz and Luckmann, 1945, p. 485–487). After careful study of the target audiences the US propagandists generated 32 audience specific archetypes in which to create propaganda and to reframe the US and allied forces as a savior against (what was framed as) the militaristic tyranny of Japan (Schmulowitz and Luckmann, 1945, p. 485–491). The same strategy was deployed in the Korean War, albeit with slightly differing attributes to their targeted audiences (Psychological Warfare in Korea, 1951; PsyWar Leaflet Archive - 141-J-1, 2012). In both theaters real-world action was taken due to creation and dissemination of information via aerial leaflet propaganda (Schmulowitz and Luckmann, 1945; Psychological Warfare in Korea, 1951; Kim and Haley, 2018). The “thought bombs” were able to target audiences, use rhetoric and modalities that resonated with the target audiences, and utilize heuristics implicit in their respective rhetoric to call to action various tribal groups in a wartime theater. Today the leaflets are still dropped over enemy territories, with the same four points of focus and categories of dissemination, but leaflet propaganda has evolved and the range of airplanes and cost of production of such analog methods are no longer limited by the physical realm of dissemination.

Now their only limitations are Internet access and that of the imagination. Internet memes (colloquially described simply as memes) are one of the latest evolutions of leaflet propaganda and an effective tool in the arsenal of digital persuasion. Internet memes' ability to utilize dense modality and cognitive biases allows them to help sew discord by consistently reaffirming preexisting tribal bonds. As the macroscopic look at aerial leaflet propaganda comes to a close the next pertinent questions arise: what exactly are internet memes and how do they parallel the strategies and tactics of aerial leaflet propaganda?

Memes and their Distribution

Unless one abstains from Internet and social media use internet memes will indubitably be something one has come across. They pervade Facebook timelines, creep into Instagram posts, serenade the Twitterverse, make the nightly news, and have become a staple of digitally based communication. According to Statista.com Facebook alone had an active user base of 2.5 billion people in the final quarter of 2019 (Clement, 2020b). Instagram and Twitter came in second and third, respectively, both boasting over 1 billion active users (Clement, 2020c). Of these 74% of Facebook users and 42% of Twitter users visit daily (Pew Research Center, 2019). These numbers are global users, displaying the awe-inspiring power of the Internet in its ability to connect people across the world. Furthermore, 35% of Gen Z and Millennial aged users of social media are statistically “very likely” to share other people's memes (Clement, 2020a). With such high numbers of people using social media it follows that memes would be a likely tool of idea dissemination.

The unique nature of internet memes alters this dynamic allowing for streamlined access to the broadcasting capabilities of the Internet (particularly social media outlets) to disseminate ideas to a wide audience. Ross and Rivers referring to the ideas of Wiggins and Bowers, describe internet memes as, “artifacts of participatory digital culture” aptly describing their functional use (as cited by Ross and Rivers, 2017, p. 1). Their ability to be created, used, disseminated, and remixed by anyone with Internet access opens doors to previously unfounded participation in regards to both societal and political issues (Anderson and Lee, 2020). In essence, each computer, smartphone, or tablet becomes a readily available tool of conveyance; distributing ideas that could potentially spread across the globe. In fact, memes have such promise in the realm of propaganda and information dissemination that the Defense Department and DARPA have studied their abilities to influence culture, reinforce ideology, and even alter behavior (DiResta et al., 2019, p. 50).

Although seemingly an empowering tool for the individual they can still function in the same manner as their analog forbearers, as a mechanism of the larger State entities and the reigning ideologies within it. Internet memes' success and failures are highly dependent upon the cultural and linguistic limits of their targeted audience. They are a product generally created for a specific [sub]culture. Although their tactics and traits have been revised for a digital medium, their entanglements with traditional methods of State sponsored psychological operations (PSYOPs) are strikingly similar. Regardless of the position or statement of a given meme its success is still bound by the cultural discussions and norms within which it is shared: a trait shared by its analog forbearers. To truly begin to understand the power of the meme its etymology and modal properties must first be explored.

Despite the popularity of internet memes their etymology often escapes the average Internet user. The word “meme” can trace its etymology to Greek “mimēsis” relating to the way in which art imitates life (Mimesis, 2020). One of the most well-known excerpts of mimesis can be found in Plato's Republic, noting how a painter may know how to represent an object, but may not know how to use one in reality. Plato writes, “An image-maker, a representer, understands only appearance, while reality is beyond him” (Plato, 2010 375 B.C.E, 70). Plato may turn out to have an apt divination for life in the Digital Age. Mimesis has a long history of study, though it was not until more contemporary times that it was attributed to social constructs and their dispersal into a given culture.

Contemporary internet memes can trace their lineage to Richard Dawkins' descriptions of memes in his seminal work, The Selfish Gene (1976). To paraphrase Dawkins' idea, memes are small bits of culture that act as if they were individual genes within the field of biology. Each artifact carries with it a piece of the culture in which it was created. To continue with the metaphor, these genes then combine to become parts of a larger genome (the larger social-consciousness) (Dawkins, 1976). In order for the gene to function within the genome it must have DNA that can be read and understood by it. Internet memes must also be able to be read and understood by their target audience to have an effect. Ross and Rivers contend that it is not only the language that matters, but also the culture, worldviews, emotions, and feelings of the audience that propels them into the broader social consciousness (Ross and Rivers, 2017, p. 2). Returning to the metaphor, these keys factors are essential ingredients that make up the nucleotides of the DNA. All of these pieces are found to be combined in internet memes, allowing them the possibility of viral power in a given culture. With the essential, yet unseen, inner workings of the internet meme in place it is the easily observable aspects that will be discussed next.

Internet memes occur in a wide range of medias but generally take the form of animations, GIFs, videos (including those found on Reddit, TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube), images, and image macros. Though all of these forms are relevant for the current article, image macros will be the focus due to their ease of creation, transmission, and adaptability as well as their comparability to traditional aerial leaflet propaganda. Due to the ceaseless creation of memes created daily no exact number of internet memes in circulation at a given time is possible. With this in mind according to one of the most popular internet meme sites, knowyourmeme.com, there are currently 3,347 confirmed archetypes/genres of image macro memes officially listed between 2003 and 2020 (Confirmed Entries, 2020). Although image macros have been highlighted here as an example other meme modalities also utilize the techniques of PYSOP driven propaganda and leaflet propaganda.

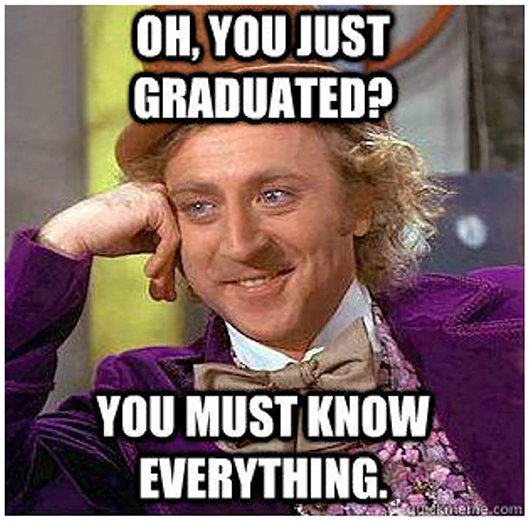

In a nutshell, internet memes using the image macro form of transmission use a static image and superimposed text. Much like the aerial propaganda dropped from planes (or handed out) both the image[s] and the text play a role in the understanding of the meme. The image relates directly to the given archetype (or genre) of the meme creating a basis for which to understand the meme. Images can relate to a wide range of expression including sarcasm, irony, humor, or advice. This “base” allows for a tacit understanding of the meme on a macroscopic level. For example, the widely known “Condescending Wonka” meme has been in circulation since 2011 (Condescending Wonka/Creepy Wonka Image #233,240, 2012) (see Figure 1). This meme features the image of Gene Wilder from the 1971 film Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory. The image itself lets the meme consumer know this specific meme will discuss some topic of an ironic nature in which the rhetorical act of condescension is applied for humorous effect. The construction of these cultural artifacts adheres to Semiotic understandings of language. Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, in their work Course in General linguistics, describes language in terms of signs, signifiers, and signified (Sassure, 2010). The power of signs has been utilized throughout the written record to bond people together under one image and idea. Internet memes harness the power of signs acculturating and reconfirming ideas of how the world really is. One of the cornerstones of the internet meme's power lies within its dense amorphous modality.

Internet memes utilize these functions to create a dense modality, allowing those experiencing memes to, at a glance, comprehend the general context (sarcasm, humor, etc.) from the static image and gain further information. The memes can then become particularly nuanced for the target culture, from the superimposed text. When the memes subscribe to the archetype conventions the signs and signifiers work in conjunction to create a hyper-modality around the signified idea. This modality falls into categories understood by the users and creators of internet memes. Using the basic archetype (i.e., the static image behind the superimposed text) of the meme generates options for nearly infinite amounts of remixing, allowing them to stay current regardless of the idea presented: As long as the meme smith adheres to the mutually understood pre-existing signifier of the internet meme. Although thousands of meme archetypes exist they can be broken down by their purpose into five umbrella categories.

Mickael Benaim, citing the work of Knobel and Lankshear formulated a list of five meme types which are as follows: “collaborative, absurdist humor in multimedia forms; hoax memes; celebrations of the absurd or unusual; and social commentary (social critiques, political comments, social activist)” (as cited in Benaim, 2018, p. 901). With such a broad array of types internet memes are able to find an audience in lead and sub cultures across the globe. The Internet is rife with millions of examples of each of these categories. The specific topics addressed range from popular culture, politics, to subcultures such as internet memes in Latin and Klingon. Each meme archetype/genre must refer to preexisting sociocultural constructs in order to be successful (in terms of being understood and shared). Memes in their final forms (the static image and the superimposed text) can also, though not always, be restricted by their linguistic and cultural capacities. Although potentially empowering internet memes are not without further limitations in regards to the roles they play in today's technologically savvy world. It should be noted that although humor is quite often the mode of conveyance the subject matter may be deadly serious. Internet memes harness a different mechanism for dispersal than aerial leaflet propaganda, yet both share similar spatial limitations dependent upon their targeted audiences.

One example of such a limitation, relating to ineffective audience targeting, played out in the real world can be found in a New York Times article, “German's Cross Signals in Propaganda Leaflets” (Associated Press, 1945) German leaflet propaganda meant for the eastern front was accidently shot toward the American held western front. The Russian language propaganda aimed at inciting rage against the American forces in the Pacific. Several minutes later the American front received the correct batch, in English, claiming, “Premier Stalin was seeking to destroy America and Britain” (Associated Press, 1945). This unintentional misfire destroyed the leaflet propaganda's ability to disseminate its intended message and displaying the cultural/linguistic range of the propaganda. It is not only the language and the message that must resonate with target audiences, but also the phrasing and cultural sensibilities implicit in the act.

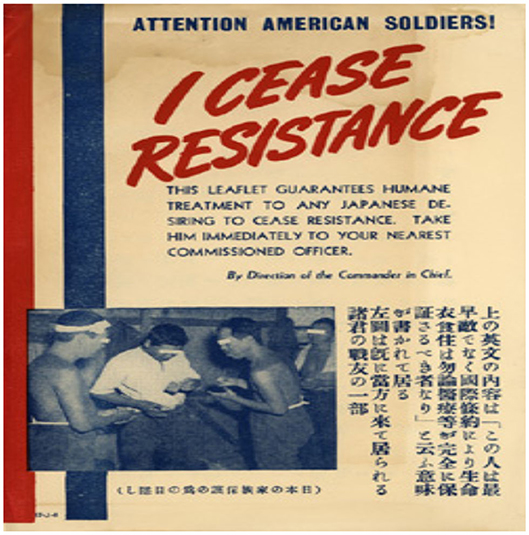

In both theaters discussed in section Thought Bombs Raining Down From Above, propagandists had to frame their language in ways that were culturally acceptable for their audiences. On striking example is the use of the statement “Cease Resistance” instead of “surrender” or “give up” (see Figure 2). In order to maintain the appearance of honor and a “shameless” exit from the war in the face of defeat, leaflet propaganda focused on using the statement “to cease resistance” to pander to the target audience's sensibilities (Schmulowitz and Luckmann, 1945; Kim and Haley, 2018). This change was made after finding previous messages to not resonate with their target audiences and even backfire into increasing enemy morale (Schmulowitz and Luckmann, 1945). Therefore, careful experimentation, hand tailored messages, and thoughtful audience targeting play vital roles in the art of aerial leaflet propaganda dispersal. Internet memes also have similar limitations imposed upon them particularly relating to their timing, culturally targeted audience, and dispersal range.

Figure 2. Jesus- We can beat it together (2016).

As theoretical comparative example, a meme shared in Japanese may not linguistically or culturally be successful with a North American audience and vice versa; although the same genre of meme may be used to infer the underlying meaning of the internet meme. Therefore, internet memes do have limitations correlating to their intended audience and their knowledge of the meme, or what it references within the social sphere, in order to work (Bradshaw and Howard, 2018). Much like dropping Spanish language aerial propaganda on a country such as Djibouti would prove ineffective it is the intended audience (and by extension their demographics, sensibilities, and tribal bonds) that creates the boundaries for the success or failure of an internet meme to become used and shared on a grander scale; much like the targeting of wartime audiences discussed in section Thought Bombs Raining Down From Above.

Furthermore, internet memes can be limited by addition of the (often non-sensical) humorous nature they convey. If they fail to uphold the given standard of their target audience or secondary audiences, and the inherent boundary markers of that culture, they will fail in propagating themselves further than the first initial recipients. Conventional PSYOPs follow similar guidelines when generating propaganda in foreign theaters. According to the declassified 2003 U.S. Army's “Psychological Operations Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures” field manual, generated materials must be, “compatible with the way foreign populations [and by extension target audiences] are accustomed to receiving information” (1–3). Therefore, the modality must match the expectations of the target audiences (Bradshaw and Howard, 2018).

In order for memes or leaflet propaganda to be successful it must capitalize on the timeliness of the event they are referencing (Coscia, 2018, p. 70). If a meme references an event too far outside of the social consciousness it is unlikely to take on a viral form. An apt comparison would be dropping World War 2 propaganda leaflets over modern day cartel held regions of Mexico. The message is simply not going to be effective and therefore its virility is squashed from the onset. The creation of effective memes follows the tides of contemporary events; often mirroring the 24-h news cycle from which many internet memes draw their cultural references. Those that target their audience well and craft the meme's narrative in a way that resonates ride the wave, while those that don't drown and sink into the inky blackness of the forgotten places of the world wide web.

Furthermore, if a meme is to be successful in their dispersion, it must not be too similar to other viral internet memes sharing the same information or they will likely face lower success of propagation. As Michelle Coscia, referring to their study conducted on the social bookmarking sites Reddit and Hacker News, writes, “high canonicity lowers the overall success of viral posts at the same time it helps non-viral posts be appreciated” (Coscia, 2018, p. 72). By saturating the meme market with similar memes those with novel approaches become more successful. Leaflet propaganda also adheres to similar dispersal boundaries. Kim and Haley (2018) discussing the strategies of leaflet propaganda in the Korean War note, “…each side copied the other's themes and content as counter-propaganda, the themes of the leaflets with an ideological appeal were somewhat similar in that they criticized the societal system of the opponent.” The remixes needed to be similar enough to act as counter-propaganda if they were to be effective tools of manipulation, but not exact copies. If an internet meme is to survive and thrive it must not be an exact clone; much like the genes behind its namesake it must evolve and mutate to survive. This not only maintains the meme genre, but also regenerates interest in the initial samplings. Through the use of remixing the original referenced artifacts become the raw materials with which to remix.

Another essential key to a memes success is its ability to remix cultural artifacts as materials to generate new meaning. Objections to the use of remix to create bona fide meaning from the references among audiences are addressed in Lawrence Lessig's groundbreaking work Remix. He writes, “Their meaning comes not from the content of what they say; it comes from the reference, which is expressible only if it is the original that gets used. Images or sounds collected from real-world examples become ‘paint on a palette'” (Lessig, 2009, p. 74). Each event that strikes a chord with a culture or subculture has the potential to add to the modality of a meme and its remixes; particularly in regards to pop-culture artifacts. This not only increases “fun” of recognizing the cultural references in a meme, but also, potentially increases its resonance with non-targeted audiences as well: further aiding in the internet memes potential for broader dispersal. In short, internet memes remix cultural artifacts to generate new meanings by leveraging the power of other cultural references for increased audience participation and dispersion (Lessig, 2009, p. 76). Therefore, an adequate sense of cultural understanding (by both meme creators and meme consumers) plays a large role in the success or failure of a meme.

The mimetic nature of internet memes must reflect and/or illuminate some aspect of the targeted audience[s] and their respective beliefs, values, and/or sensibilities. They play upon “preexisting social and cultural constructs; norms; values or specific environments” in order to be successful at both transmitting their idea and being shared (Benaim, 2018, p. 901). They must utilize specific lexicons, symbols, and ideas within the [sub]culture to spark interest among those that share a form of common identity. This same rule applies to traditional methods of PSYOPs as well, “different lines of persuasion and symbols will need to be developed or selected to influence the [target audiences] to achieve each of the different [supporting Psychological Operations objectives]” (US Army, 2003, p. 5–2). Otherwise, much like the aforementioned cartel held Mexico example stated, they will flounder in their attempts of disseminating within and outside of their target audience.

Humor has oft been cited as one of the primary functions of internet memes (Piata, 2016; Ross and Rivers, 2017; Benaim, 2018). Being known as such among the general populace internet memes may be simply brushed aside as a joke rather than sincere ideological, informative, or political commentary of the meme sharer. Although it should be noted this may indeed be the end goal of many internet memes to begin with: a brief chuckle to add a bit of spice to life or a cathartic aid. This aspect of humor may also aid in the propagation of the internet meme continuing its dissemination and that can be later capitalized upon (via audience building) until it finds an audience that embraces targeted ideas as axiomatic.

The ability of memes to be created and disseminated quickly makes them an effective instrument of information propagation. During national or worldwide events memes will appear across social media platforms; displaying their timeliness in novel fashion. In 2016 political memes revolving around the U.S. election swept the internet along with memes of Harambe the gorilla (Haddow, 2016; Judah, 2017). In 2020, internet memes referencing the spread of COVID-19 (particularly relating to the rush on toilet paper, political leader's stance's on the disease, and “cures” in the U.S.A.), presidential candidates (including President Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, and Joe Biden), economic and social policy, and anti-vaccination are all commonplace on social media platforms. Meme creators and those that share them can (and do) in real-time, with minimal fear of social backlash or censorship. The efficiency of their production and range parallels that of aerial leaflet propaganda; information falling out of the sky and into the minds of those who happen to come across it: with little fear of “enemies” halting its immediate affects. The primary differences lie in internet memes ability to be up-to-the-minute, anonymous, malleable, and capable of being harnessed by the individual. The following section will discuss in more detail why they are useful for spreading ideas, particularly those relating to politics, social issues, and more pragmatic subject matter due to the option of meme smith's anonymity.

The Death of the Meme Creator: Enter the Remix

The ability to create and disseminate quickly aids in the anonymity of the source of memes; be they State actors or private individuals. Ross and Rivers, as well as Cannizarro, note that internet memes encourage the anonymity of their origin and empower those who would not otherwise likely engage in political or confrontational dialogue, regardless if the information is based in factual evidence or not (Cannizzaro, 2016; Ross and Rivers, 2017). In brief, part of the draw of internet memes for many people (those creating or sharing them) is their ability to remain constantly contemporary through continual remixing and anonymous creation.

The “death of the meme creator,” to borrow from Roland Barthes', The Death of the Author, erases the problematic notions of creation (i.e., who created it and the creator's truth behind it) and allows for sharing and remixing to be a community based exercise in liberty. As Barthes writes, “the explanation of a work is always sought in the man or woman who produced it,” but without a face or name to turn to the internet meme exists in a permanent state of inference and translatability; an object protean by nature (Barthes, 2010, p. 1322). Those who share or remix internet memes are not held to a standard or a limitation of the author who created it. The internet memes meaning lies not in the mind or stances of the meme creator, but that of its destination, the meme consumer. The limit is only that of imagination and its ability to stay temporally trendy.

The ability to immediately separate the creator of the meme and the meme itself adds a curious level of freedom to interpret the meme. In a Pew Research study, “U.S. Media Polarization and the 2020 Election: A Nation Divided,” notes, “evidence suggests that partisan polarization in the use and trust of media sources has widened in the past 5 years” primarily due to distrusted sources of information (Jurkowitz et al., 2020). As media finds itself in an age of increasing media polarization memes offer information dispersion that generally lack an obvious political point of origin. Internet memes are a generally authorless product freeing their audiences from the shackles of authorial expectation. This allows for multiple levels of understanding to emanate from the locus (the meme) aiding in the enjoyment, befuddlement, catharsis, or manipulation in the marketplace of ideas. As there is generally no author/creator to utilize preexisting political biases audiences who come across political memes have a chance to view them without their own bias filters on guard. In short, the language itself and the impression left on the minds of the audience that generate their own meanings and understanding of the meme.

It is here that memes diverge from analog leaflet propaganda. Although the exact creators may not be known the targeted audience is aware of their point of origin. This creates a much more difficult task for the traditional propagandist. Internet memes aided by symbolism, cultural understanding, and accurate audience targeting utilize the death of the meme creator to manipulate audience heuristic understandings of the world. In order to do so it must first cast a wide net through trendiness and remixing ideas that are attractive to a target audience.

To maintain their trendiness internet memes must create or capitalize upon a culture's symbolic value archetypes in real-time. Benaim writes, “Internet memes are far from simple regressive online production, since they incorporate high symbolic values from a lead culture” (Benaim, 2018, p. 904). By taking aspects from the real world and placing them into internet memes they create new meanings, symbols, language, and knowledge (Benaim, 2018). These creations are not novel but rely on “samplings” (to steal a phrase from the music industry) of culture therefore creating a novel take on the idea or event. Ross and Rivers note the ability of people to contribute to the meme writing, “creators are able to either alter the specific meaning to be expressed through the text or to create a new iteration of the meme or to change the image and the text to create a new derivative meme entirely” (Ross and Rivers, 2017, p. 2). This leads to greater participation within the culture or linguistic group of the memes referential material.

Although many meme smiths prefer to remain anonymous there are some who prefer to make themselves known via social media pseudonyms. One particularly striking example is of Twitter user “CarpeDonktum” who visited the White House as part of President Donald Trump's “Social Media Summit” in July of 2019 (Relman, 2019; Roose, 2019). This is perhaps evidence of an emerging market for meme creators within political and social spheres of society: but, for now, it remains a unique example swimming upstream among the anonymous masses generating memes today.

The greater potential for remixing and/or creates an opportunity to take power out of the hands of State entities or corporations and places it in the hands of small groups and/or individuals. To highlight this advantage, there is a low entry barrier for anyone willing to participate: and they do. Lessig, referring to the growth of participation in creating memes, writes, “This means more people can create in this way, which means that many more do. The images or sounds are taken from the tokens of culture, whether digital or analog” (Lessig, 2009, p. 71). In the past such activities would rely heavily on high dollar advertisement campaigns, physical materials, and substantial brain and manpower. No longer are planes, paper, and people trained in psychological warfare necessary to propagate leaflet propaganda; all it takes is an individual, an Internet connection, and the understanding of a target audience. Once a target audience has been determined internet meme creators with malevolent or mischievous intent utilize cognitive biases to garner further influence.

Heuristic Attack of the Memes

The human brain can only handle so much conscious information at a time. It uses heuristics to help people navigate through the world without devoting too many cognitive resources to do so. Psychologist Christopher Dwyer, paraphrasing the work of West, Toplak, and Stanovich, notes that, “heuristics allow one to make an inference without extensive deliberation and/or reflective judgment, given that they are essentially schemas for such solutions” (as cited by Dwyer, 2018). These heuristic properties of human thinking can be exploited leading to cognitive biases. These biases can be effectively gamed by internet memes and the people or groups which create and share them. There are several keystone biases at play in viral memes: confirmation bias, homogeneity bias, and popularity bias. Each uses their own specialized tools to propagate misinformation and propaganda. In addition they also help craft the [de]legitimization of ideas, people, and social movements.

Confirmation bias focuses on the things and ideas people find to be agreeable or sensible to their respective worldview. If information aligns with previously held beliefs, be they true or misplaced, they are more likely to believe it. Shahram Heshmat, writing in Psychology Today, states, “Once we have formed a view, we embrace information that confirms that view while ignoring, or rejecting, information that casts doubt on it (Heshmat, 2015)”. The bias takes on a 2-fold purpose, reconfirming one's initial stance on an idea and discriminating against ideas that do not reconfirm it. This bias allows for an echo chamber of ideas to be consumed and shared throughout the web (Ciampaglia, 2018). Facebook has highlighted the malevolent use of this bias in press releases after the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Facebook, in a public release, noted the use of this bias in false amplification of ideology driven Facebook pages. Facebook defined false amplification as, “Coordinated activity by inauthentic accounts with the intent of manipulating political discussion” the goals being, “discouraging specific parties from participating in discussion, or amplifying sensationalistic voices over others” (Weedon et al., 2017). The public release also notes that false amplifiers can be “professional groups” targeting specific demographics or “a smaller number of carefully curated accounts that exhibit authentic characteristics with well-developed online personas” giving power both to States and institutions as well as the individual or small group (Weedon et al., 2017). These tactics mirror conventional PSYOPs tactics. Traditional methods use by PSYOPs to disseminate propaganda, including leaflet propaganda, utilize “primary groups” and/or “secondary groups” to achieve the goals of their operations.

Primary groups, “prefer to receive information from other members in the group and tend to shun information from outsiders,” making for easy audience targeting due to the inherent echo-chamber structure of the group (US Army, 2003, p. 3–5). The caveat of such targeting is that these groups generally do not have mass influence in the public sphere. On the other hand secondary groups consist of large numbers of people and viewpoints bonded together through a common objective or idea. Secondary groups can be manipulated via aggregation, based on physical location, or through the medium of a key communicator (e.g., celebrities, politicians, authority figures, etc.). Furthermore, due to the variability of viewpoints and backgrounds secondary groups freely use and disseminate information from sources: casting a larger net for prospective target audiences (US Army, 2003, p. 3–5). Succinctly, contemporary memes mirror traditional PSYOPs through their use of false amplification via digital key communicators. Be it a meme page, a celebrity's Twitter account, or a teacher's Facebook page memes are able to utilize their respective position in society to [de]legitimize ideas and people. Once information has been disseminated and accepted (as either inherently true or false) further solidification of in-group bonds becomes a likely outcome. Regardless of the size and scope of those behind the page they all utilize a combination of sensationalist “news,” internet memes, and other forms of information dissemination to try to alter the political and social discourses taking place on their medium (Weedon et al., 2017). The confirmation of one's ideas can be a powerful tool. Allowing for one to feel accepted as part of an “in-group.” These “in groups” can be comprised of nearly any point of view and appear across social networks creating social bubbles based on a homogeneity bias.

Statistical data confirms that social media platforms are ripe social bubble fields ready to be tilled until their cognitive bias crops bear their harvest. According to Schmidt et al. users limit their activity to a small number of like-minded Facebook pages resulting in severe selective exposure (Schmidt et al., 2017). Furthermore, users confine themselves to a select range of pages or news outlets that quite often aid in reconfirming their beliefs and ideas (Schmidt et al., 2017). Such pages utilize memes (particularly image macro memes) to reconfirm and disseminate their pages respective point of view or guiding ideology. In short, social media users are bolstering their own claims and cognitive biases based upon what they already believe to be true. This aids in limiting their personal worldview and, on a grander scale, in participating in strong user polarization across the globe.

Nikolov et al. (2015), in Measuring Online Social Bubbles, found that users of Twitter and email are limiting their access to information, in regards to the range of their sources, in comparison to a general search baseline; once more aiding in the [re]confirmation of ideas. While this may be trivial in many instances of internet memes, these can serve as legitimate forms of propaganda aided by the algorithms, used by search engines and social media alike, to show users more of what their platform behavior indicates they prefer. By limiting oneself in the pages they view, the internet memes and news sources they gain insight from, and the lack of diversity of ideas encountered, users may be inadvertently handicapping their understanding of objective reality; leading to the potentially more dangerous activity of political astroturfing.

Political astroturfing paves the way to gather large numbers of people into social bubbles and instigates a popularity bias. Ratkiewicz et al. defines political astroturfing as, “political campaigns disguised as spontaneous ‘grassroots' behavior that are in reality carried out by a single person or organization” (Ratkiewicz et al., 2011). As previously mentioned internet memes are easily created, shared, and remixed making them a malleable tool for States and individuals with an ideological imperative. By utilizing internet memes and other digital tools such groups can effectively create and organize large groups of users into social bubbles that act as echo chambers (Weedon et al., 2017). These pages or users are initially works of fiction with the guise of reality. As users are targeted (through advertisements or user behavior patterns) the pages targeting users become populated with real users; disguising the malevolent intent behind the page's creation. Utilizing a popularity bias, users may no longer invest time and effort into fact checking the information disseminated by such pages.

The fainéant nature of users throws fact checking and verification into the wind stirring up a typhoon of misinformation that can quickly spread across the Internet. Rather than the internet memes credibility or truthfulness it is its, “catchiness and repeatability [that] can function as the primary drivers of information diffusion” (Ratkiewicz et al., 2011). To put it succinctly, internet memes ability to entertain or be easily remembered give it greater claim and viral ability than its accuracy. Notions of what is true, or even remotely possible, lie in wait within the heuristic properties of the internet memes. Similar tactics were used, revised, and iterated in the creation and dispersal of leaflet propaganda as partially discussed in section Thought Bombs Raining Down From Above of this article. Although leaflet propaganda (and by extension memes) that inhabit the realm of possibility can be accepted as truth, the truth itself may appear unbelievable by target audiences.

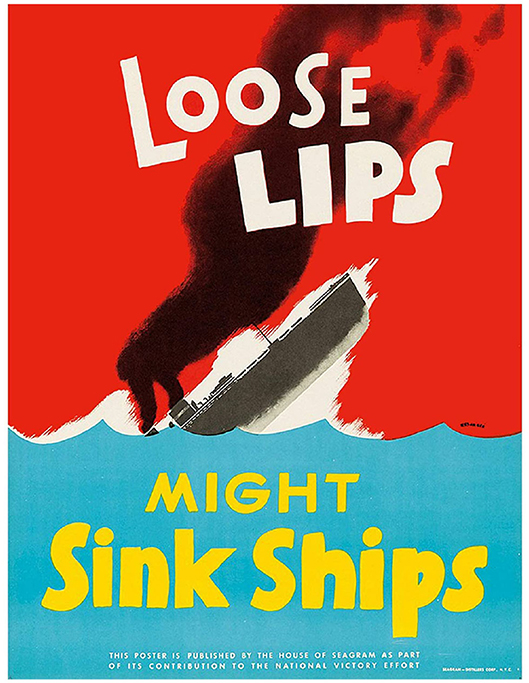

This notion of catchiness and repeatability echoes the tactics of Allied World War II leaflet propaganda. Martin F. Herz notes that slogans such as “Better Free Than Prisoner-of-War, Better a Prisoner-of-War Than Dead” proved effective in manipulating the behavior and ideas of the enemy combatants” and helped to maintain operations security (OPSEC) within the allied forces with the phrase “loose lips might sink ships” (see Figure 3) (Loose Lips Might Sink Ships, 1941; Herz, 1949). Also in the Korean War statements such as “A live patriot can help Korea more than a dead one” were common in aerial leaflets dropped over enemy territory; giving a simple, repeatable maxim to the target audiences (Psychological Warfare in Korea, 1951). Furthermore, in interviews with the US Fifth Army's POWs in Italy they found that claims that are factually truthful could appear to be outrageous claims by enemy combatants. The example cited is that all POWs “received eggs for breakfast,” while true, POWs claimed that, “This idea was so preposterous to Germans on the other side of the firing line that they simply laughed at the idea” (Herz, 1949, p. 473). In order to be effective manipulation tools (be they leaflet propaganda or internet memes) they must walk a fine line between reality and believability.

Figure 3. Oregon Trail Toilet Paper Meme (2020).

Utilizing heuristics and cognitive biases have aided humans in their survival as well as their gullibility. As of January 2020 the number of active internet users worldwide is nearly 4.5 billion opening the door ever wider for the use and spread of internet memes for malevolent purposes (Clement, 2020c). In the realms of politics and ideology these tools are often combined to [de]legitimize ideas, political candidates, and social movements. The aforementioned keystone biases aid in building tribal bonds and create “Other” groups that compete for information dissemination domination among the meme marketplace. Much like the propagandists mentioned in section three groups will use, remix and iterate the malleable form of the image macro meme to “combat” ideas not supporting their narrative through the tools of [de]legitimization.

Internet memes, along with their previously mentioned targeting biases and tools, can act as agents of [de]legitimization. Legitimization works to shine a positive light on an idea or person by highlighting the good qualities inherent in the subject. Delegitimizing focus on finding the negative components; but also aids in the “Othering” of groups who may find said ideas to be a positive thing. Ross and Rivers note this quality among internet memes writing, “delegitimization demonstrates the absence of rhetorical alignment with the prevalent social values of the time in addition to the absence of positive, beneficial, ethical, understandable action” (Ross and Rivers, 2017, p. 3). It takes no stretch of the imagination to understand how this can play out in the digital world.

By finding like-minded people and utilizing the cognitive biases built into the social media construct the reality of a given situation can take on a phantasmagoric form. Each person delves further into their own hand tailored version of reality, legitimizing information that agrees with their preconceived notions and finding delegitimizing information (that agrees with their stance) as further evidence of their worldview being correct. By finding other people or groups who share similar dispositions an idea of an other will emerge. This strategy is not novel. Politicians, governments, and companies have used it since time immemorial. The medium has simply taken on a viral form now capable of being wielded by States, institutions, corporations, and individuals alike.

For instance, the U.S. Army noted that a target audience with “needs, wants, and desires… will, at varying levels of effort, strive to satisfy them” (US Army, 2003, p. 5, 6). If the desire is to have a voice, to spark change, or to express oneself and their opinion every person now has a medium to do so. In addition, “The desire of the [target audience] to fulfill, alleviate, or eliminate a need provides the motivation for them to change their behavior” (US Army, 2003, p. 5, 6). By exploiting the needs and heuristics of target audiences the creators of memes, particularly those with malevolent intentions, can expand their reach across the globe and create tribal groups without the necessity of people actually being in a geographic location. People are given a “weapon” and a means to alleviate their needs, but they may be inadvertently letting someone else aim. The needs of a group can take the form of micro or macro behaviors on the Internet and/or the real world and need only a singular point of agreement to begin forming Othering tactics. Guttormsen, notes on the scope of boundary markers that can lead to Othering range from supra-national to local and include the realms of the “political, cultural, social, professional, and legal spheres” (Guttormsen, 2018, p. 324). These realms may only need a single act of meaning-attribution to a person, group, or idea to set in motion the gears of Othering (Guttormsen, 2018, p. 326). Once the gears have been set in motion it raises the possibility of subjecting itself to the aforementioned cognitive biases resulting in the sharing of flawed information via internet memes; perhaps further distancing groups viewed through polarizing lenses. The following section briefly displays several notable examples of how these strategies have played out in the real world.

Memes in Action

The use of internet memes to try and alter the thoughts and actions of people has become better documented over the past decade. This section is devoted to several real-world examples of internet memes at use, by both States and individuals. One of the most studied instances is in relation to the Internet Research Agency (hereafter IRA) and their role in cyber influence operations. It should be noted due to the vast amount of research available for each respective example the following selection of real-world actions given are intentionally succinct and meant to be a cursory gander at how internet memes have been used in the real-world.

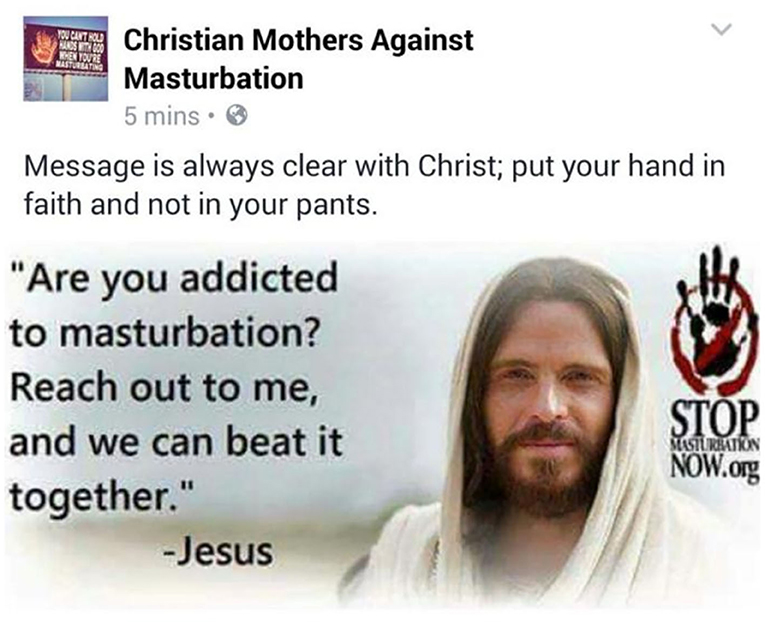

The IRA appears to have had several goals including a long term “social influence operation consisting of various coordinated disinformation tactics aimed directly at US citizens” with the goal of, “exert[ing] political influence and exacerbat[ing] social divisions in US culture” (DiResta et al., 2019). In 2016, alone the IRA generated or repurposed over 167,000 memes on Facebook and Instagram with millions of user interactions across platforms focused on the organic communities they had created over time (DiResta et al., 2019, p. 51–58). Each page operated by the IRA was specifically tailored to targeted audiences focusing on polarizing issues, public figures, and identity (DiResta et al., 2019, p. 11). Religious, minority, and political groups were heavily targeted for their ability to create echo chambers. Furthermore, posts created by these pages began with producing narratives such groups may find appealing, disseminating them using targeted advertisements, and eventually posts that “intended to elicit outrage” and real-world action (Howard and Liotsiou, 2018, p. 19). In order to increase the number of potential users viewing their content these pages would initially rely heavily on internet memes focused on humor to create organic interactions. For example two IRA created Facebook pages, Army of Jesus and Christian Mothers Against Masterbation, focused on religion and sexual addiction. One popular meme, focusing on masturbation, was made and remixed multiple times and initially shared via Facebook and Instagram. The meme featuring apparent depictions of Jesus Christ reads, “Struggling with the addiction to masturbation? Reach out and we will beat it together” (DiResta et al., 2019, p. 40; Jesus- We can beat it together, 2016) (see Figure 4). This meme utilized a real-world issue in conjunction with a sexual pun leading to content being shared by its targeted and non-targeted audience alike (DiResta et al., 2019, p. 40). By doing so it increased the likelihood of reaching targeted audiences via non-targeted audience participation; furthering their purpose in the long run by increasing interactions and page visibility.

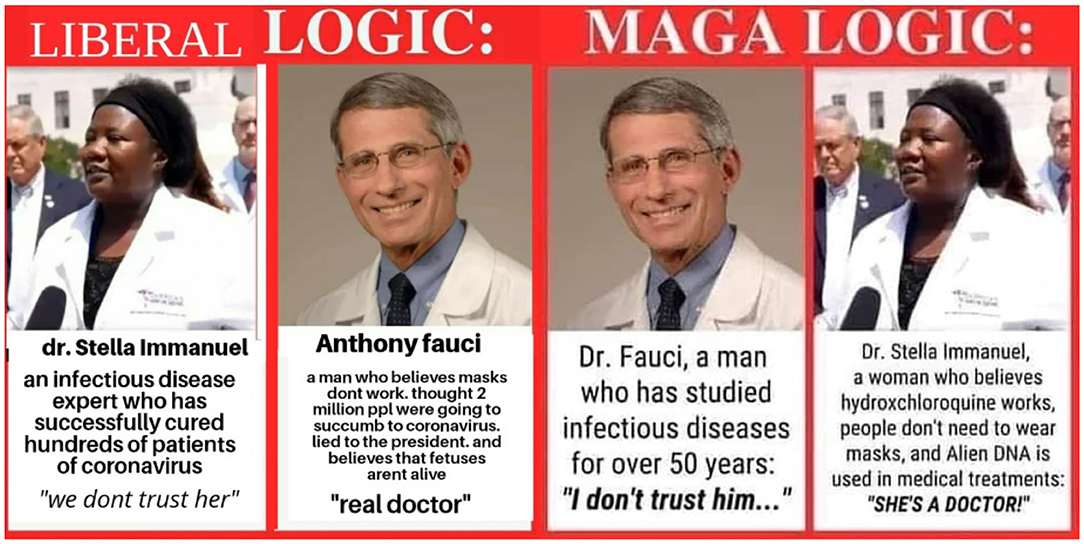

Figure 4. Liberal Logic Meme (2020) vs. MAGA Logic Meme (2020).

The dense modality of their memes aided in the viral spread by pandering to their target audience via reinforcement of views, interaction by those criticizing them, or people who simply found them funny. All of which aided in their organic spread helping to increase the anonymity of their origin and their opaque goals. The continued use of such tactics hints that those creating and using them are finding them useful to their purposes. Through the use of the aforementioned cognitive biases as well as other strategies the IRA created a definite footprint on the internet and digital culture. Another instance of memes altering the dialogue around an issue can be found in Croatia and the Caća se vrača meme initiative surrounding former Prime Minister Ino Sanader.

Bebić and Volarevic studied the spread the influence of Caća se vrača (the father is coming back) in Croatia finding that memes “may have influenced the media reporting,” in regards to [re]legitimizing Ino Sanader after his release from prison (Bebić and Volarevic, 2018, p. 53). Their data suggests that Sanader's public opinion went from neutral to positive in news broadcasts following the satirical-meme initiative. Piata found similar results in the Greek elections of 2015. Through the use of metaphor and humor both political parties utilized social media and memes as tools of [de]legitimization (Piata, 2016, p. 53). Using the popularity bias implicit in their respective messages nabufested in increased communication between targeted and non-targeted audiences. Corporations have also been subject to the attacks of individuals and groups via internet memes.

Ross and Rivers, highlighting the work of Davis et al. (2016), exampled Greenpeace's “Let's Go!” campaign and their use of internet memes to delegitimize Shell Oil company's advertising via irony. One example's background picture features an oil platform and the superimposed text reads, “Because fuck you, earth. Let's Go” (Ross and Rivers, 2017, p. 4). Remixing a company's advertisement campaign to display irony was a novel approach to internet meme information dissemination; taking the power away from a large corporation and placing it in the hands of those concerned with various social and environmental issues. This meme series also created the foundation necessary for Othering and delegitimization of the corporation by playing with the catchiness and repeatability allowing the memes greater likelihood of dispersal among targeted and non-targeted audiences. This trend continues today and can be seen being created and disseminated by individuals in regards to the COVID-19 pandemic.

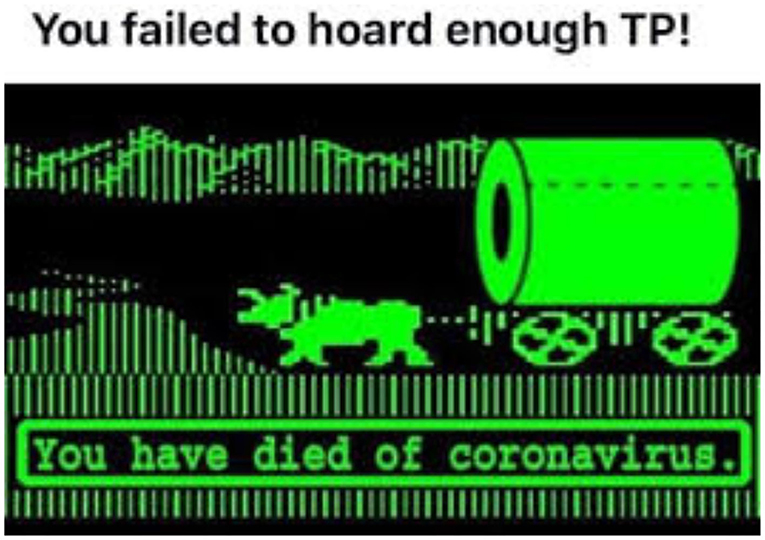

Much like any other large socially relevant event the COVID-19 pandemic has created an assemblage of memes revolving around it. Many memes being produced focus on the humor or puerile attempts of people to be prepared for social distancing, protecting themselves, or panic buying. Common memes being shared have highlighted the panic buying of toilet paper, misinformation regarding how to “cure” or inoculate oneself against the virus, and the use of nationalist based rhetoric and the responses of political leaders and other secondary individuals/groups to its spread.

One example from Covid-19 Archive, but originating Facebook, uses a screen shot from Twitter featuring the popular 1974 computer game Oregon Trail depicting an ox pulling a wagon that looks like a roll of toilet paper. Underneath of the wagon, remixing the same script and style as the game, it states, “You have died of Corona Virus.” Above the static image the superimposed script reads, “You failed to hoard enough TP [toilet paper]” (Oregon Trail Toilet Paper Meme, 2020) (see Figure 5). This particular meme pays tribute to a game initially created to educate people about the hardships faced by those traveling the length of the country in the 1,800 s. It ironically compares it to the “struggles” and “dangers” faced by people living in the twenty-first century without enough toilet paper; a theme many audiences may find humorous. Furthermore, it makes it contemporary by including the toilet paper imagery, highlighting the absurdity of the toilet paper hoarding phenomenon of early 2020, and commenting on the power of fear to inspire action within a populace. This meme appears intent on utilizing humor to point out the absurd rather than a call to action. Though other memes have begun ideological Othering tactics.

Figure 5. PsyWar Leaflet Archive - 141-J-1 (2012).

Another example shines a spotlight on the aforementioned tactics and strategies of memes and their counter-memes. In mid, 2020 memes began appearing across social platforms (including, but not limited to, Reddit, Facebook, 9gag, and Twitter) memes depicting opposing viewpoints about Dr. Anthony Stephen Fauci and Dr. Stella Immanuel (Liberal Logic Meme, 2020; MAGA Logic Meme, 2020) (see Figure 6). The memes mimic and remix each other in multiple iterations underscoring the various [de]legitimizing characteristics of each for their targeted audiences. In the “Liberal Logic” meme Dr. Immanuel's photo is positioned on the left (placing her first for audiences who read and view documents left to right) and her experience in the field leading to “successfully cur[ing] hundreds of patients with corona virus” is touted as proof of her position as an expert worth believing. This is followed up by the opposing viewpoint “we don't trust her” underneath. On the other hand, Dr. Fauci is painted in a malevolent light positioned on the right (leading the reader to be lead into the claims about Dr. Fauci only after seeing Dr. Immanuel's posited position) noting previous claims as his position as the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in the early days of the COVID-19 response. Furthermore, one more example of audience targeting enters the claims against Dr. Fauci noting, “and believes that fetuses aren[‘]t alive”; an added bonus to target a pro-life audience in which the message may further resonate. Underneath his photo is the statement, “real doctor” intended to be meant sarcastically.

On the opposing side of this example is the “MAGA Logic” meme. Note the reversal of the photos (Fauci is now on the right) and Dr. Fauci's experience as an infections disease expert for half a century is highlighted with the statement, “I don't trust him…” underneath. Dr. Immanuel is positioned on the left featuring statements that delegitimize her stances seen in the aforementioned “Liberal Logic” meme including the notion that “alien DNA is used in medical treatments” with the phrase “She's a doctor” placed underneath. These two examples are a brilliant display of the mirroring capacity of memes and counter-memes and their aforementioned targeting strategies at work. Each specific meme is targeted for their intended audience, utilizes modality to convey layered meaning, utilizes contemporary culture and society as a reference point, is up to date with the current news cycle of information that meme consumers will most likely be familiar with, and helps to solidify the tribal bonds and their implicit heuristics.

Another example bases its premise on the origin of the COVID-19 virus. The meme archetype has been dubbed the “China Virus” meme appearing after President Donald Trump began referring to COVID-19 as such in March 2020 (Viala-Gaudefroy and Lindaman, 2020). Memes based around this archetype typically use a zoomed in photo of President Trump's notes at a press conference. His left hand is visible appearing to be saving the line in which he is reading from. An even further enhancement displays an edit in which “Corona” has been crossed out and “Chinese” has been written above it, formulating the phrase “Chinese Virus” (Chinese Virus, 2020). This screen shot was, shared on social media as well as in traditional media mediums, remixed across media platforms, and has become a popular referential phrase in the social consciousness. Unlike its analog predecessor such massive distribution and rhetorical effect could only be dream of for the propagandists creating aerial leaflet propaganda in the past and present theaters of their dispersal.

The usage of the phrase has created a dynamic labeling the virus and its origins as a way to personify it as a foreign impurity and allows those affected globally their to focus their collective angst toward. The meme acts as another method of dissemination along with other forms of medias. Although the virus does indeed appear to have originated in Wuhan, China the effects of such rhetoric are felt by Asian-Americans. In the United States between March 19 and April 15, 2020 1,497 discrimination complaints were filed in relation to interactions revolving around COVID-19 (Zhou et al., 2020). Although there was no direct call to action based on the meme and interactions may be coincidental, the effects of the meme on rhetoric within the social consciousness are verifiable. This particular meme archetype could be used for further research opportunities in exploring correlations between trending internet memes and real-world interactions. As the virus runs its course and people continue to react internet memes will indubitably play a part in the public perception and reaction to COVID-19 and any further large scale events.

Final Discussion

Relatively cheap computing power and the Internet have led to the great collection of peoples cast under the banner of a globalized humanity having greater access and agency among each other than any previous time in history. Despite the great possibilities of such technology the same tools that have found success in bridging the gaps between differing peoples and cultures have evolved to fit the times. Tribalism, in the various forms it takes, still remains as part of the human condition and there are individuals, corporations, and state affiliated actors willing and able to maliciously exploit the newly found bridges between differing peoples. Internet memes have become the digital successor of leaflet propaganda and look to be the first digital version in the evolutionary sequence of things to come. Their ability to harness viral modality, prey upon heuristics and cognitive biases, and be exploited by corporations, nations, political parties, and individuals alike changes the historical power dynamic. In some ways internet memes level the playing field and in others they open the door for an era of mass digital manipulation.

This article has highlighted the facets of memes as the digital modern leaflet propaganda, but while in doing so a number of research possibilities have been discovered. More contemporary academic research into the role and effectiveness of contemporary aerial leaflet propaganda in the digital age is sparse. This opens lanes of research that prior scholars not competing with the dispersal properties of the internet could not have had insight into. There is also a dire need for further research into how [blatant] misinformation can be combatted by both platforms and individuals. Also, research into digital public reactions (via internet memes) during times of global panic could shed light on how and why people react to international stresses, particularly in areas of catharsis and personal empowerment. Furthermore, strategies to track viral memes across platforms could offer valuable insights into the collective digital consciousness of the twenty-first century. Historically based tracing of the evolution of memes and their use of technology (i.e., newspapers, radio, television) may offer insights into the future praxis. Unfortunately, due to the great wealth of data stored privately by social media companies and governments it appears to be nearly impossible to study these phenomena in real-time. As stated as a concluding thought to Psychological Warfare in Korea 69 years ago, “In psychological warfare we have an inexpensive, effective weapon that is bound to prove more effective as we continue to learn to perfect our technique” (Psychological Warfare in Korea, 1951). As the techniques and targeting power of meme creators bent on goal orientated information dissemination, to alter the hearts and minds of people globally, the effective weapon of aerial leaflet propaganda has become potentially even more effective in its digital iteration the internet meme. Perhaps for the time being its best to try to have a laugh at the times and share some internet memes. For now perhaps it is best to enjoy the laugh for the world of tomorrow may look back and find internet memes to be nothing to joke about.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

JN contributed to the design and implementation of the research topic, to the analysis of the results and writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Anderson, J., and Lee, R. (2020). Concerns About Democracy in the Digital Age. Pew Research Center; Internet, Science & Tech. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/02/21/concerns-about-democracy-in-the-digital-age/ (accessed March 2, 2020).

Associated Press (1945, January 27). German's cross signals in propaganda leaflets. New York Times (1923-Current File) New York, NY.

Barthes, R. (2010). “The death of the author,” in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd Edn. ed V. B. Leitch (New York, NY: Norton), 1322–1326.

Bebić, D., and Volarevic, M. (2018). Do not mess with a meme: the use of viral content in communicating politics. Commun. Soc. 31, 43–56. doi: 10.15581/003.31.3.43-56

Benaim, M. (2018). From symbolic values to symbolic innovation: internet-memes and innovation. Res. Policy 47, 901–910. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.02.014

Bradshaw, S., and Howard, P. N. (2018). Troops, Trolls, and Troublemakers: A Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation. Computational Propaganda Research Project. University of Oxford. Available online at: http://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2017/07/Troops-Trolls-and-Troublemakers.pdf (accessed December 17, 2018).

Cannizzaro, S. (2016). Internet memes as internet signs: a semiotic view of digital culture. Sign. Syst. Stud. 44, 562–586. doi: 10.12697/SSS.2016.44.4.05

Chinese Virus (2020). Know Your Meme. Literally Media Ltd. Available online at: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/events/chinese-virus (accessed May 20, 2020).

Ciampaglia, G. L. (2018). Biases make people vulnerable to misinformation spread by social media. Scientific American. Available online at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/biases-make-people-vulnerable-to-misinformation-spread-by-social-media/ (accessed March 1, 2020).

Clement, J. (2020b). Top U.S. mobile social apps by users 2019. Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/248074/most-popular-us-social-networking-apps-ranked-by-audience/ (accessed March 10, 2020).

Clement, J. (2020c). U.S. young adult and teen social content sharing 2019. Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/459134/young-adult-teen-social-content-sharing-usa/ (accessed January 27, 2020).

Clement, J. (2020a). Facebook - statistics & facts. www.statista.com. Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/topics/751/facebook/ (accessed February 13, 2020).

Condescending Wonka/Creepy Wonka Image #233,240 (2012). Digital Image. Knowyourmeme.com. Available online at: https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/233240-condescending-wonka-creepy-wonka (accessed June 10, 2020).

Confirmed Entries (2020). Know Your Meme. Available online at: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes (accessed March 30, 2020).

Coscia, M. (2018). Popularity spikes hurt future chances for viral propagation of protomemes. Commun. ACM 61:70. doi: 10.1145/3158227

DiResta, R., Shaffer, K., Ruppel, B., Sullivan, D., Matney, R., Fox, R., et al. (2019). The Tactics & Tropes of the Internet Research Agency. DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska: Lincoln. Lincoln, OR: Congress of the United States.

Dwyer, C. (2018). 12 common biases that affect how we make everyday decisions. Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers. Available online at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/thoughts-thinking/201809/12-common-biases-affect-how-we-make-everyday-decisions (accessed January 22, 2020).

Guttormsen, D. S. A. (2018). Advancing otherness and othering of the cultural other during ‘Intercultural Encounters' in cross-cultural management research. Int. Stud. Manage. Organ. 48, 314–332. doi: 10.1080/00208825.2018.1480874

Haddow, D. (2016). Meme warfare: how the power of mass replication has poisoned the US Election. The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/04/political-memes-2016-election-hillary-clinton-donald-trump (accessed Janaury 11, 2020).

Herz, M. F. (1949). Some psychological lessons from leaflet propaganda in world war II. Public Opin. Q 13:471. doi: 10.1086/266096

Heshmat, S. (2015). What is confirmation bias? Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers. Available online at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/science-choice/201504/what-is-confirmation-bias (accessed March 2, 2020).

Hoard Moar TP: Toilet Paper Crisis (2020). Know Your Meme. Available online at: https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1786391-toilet-paper-crisis (accessed March 16, 2020).

How a Dead Gorilla Became the Meme of 2016. (2017, January 1). BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-38383126 (accessed January 17, 2020).

Howard, P. N., and Liotsiou, D. (2018). The IRA, Social Media and Political Polarization in the United States, 2012-2018. Computational Propaganda Research Project. University of Oxford. Available online at: https://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp- content/uploads/sites/93/2018/12/The-IRA-Social-Media-and-Political-Polarization.pdf (accessed December 12, 2019).

Jesus- We can beat it together (2016). Digital Image. Knowyourmeme.com. Available online at: https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1074717-jesus (accessed June 10, 2020).

Judah, S. (2017). How a Dead Gorilla Became the Meme of 2016. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-38383126 (accessed December, 11, 2019).

Jurkowitz, M., Mitchell, A., Shearer, E., and Walker, M. (2020). U.S. Media Polarization and the 2020 Election: A Nation Divided. Pew Research Center's Journalism Project. Available online at: https://www.journalism.org/2020/01/24/u-s-media-polarization-and-the-2020-election-a-nation-divided/ (accessed March 3, 2020).

Kim, S., and Haley, E. (2018). Propaganda strategies of korean war-era leaflets. Int. J. Advertis. 37, 937–57. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2017.1348434

Lessig, L. (2009). Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. New York, NY: Penguin.

Liberal Logic Meme (2020). Digital Image. Imgur. Available online at: https://imgur.com/KEnhqy8 (accessed August 6, 2020).

Loose Lips Might Sink Ships (1941). House of Seagram, 1941–1945. National Archives and Records Administration. Available online at: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/513543

MAGA Logic Meme (2020, August 2). Digital image. 9gag.com. Available online at: https://9gag.com/tag/anthony-fauci (accessed August 6, 2020).

Mimesis (2020). Merriam-Webster. Available online at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mimesis (accessed January 26, 2020).

Nikolov, D., Oliveira, D. F. N., Flammini, A., and Menczer, F. (2015). Measuring online social bubbles. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 1:e38. doi: 10.7717/peerj-cs.38

Oregon Trail Toilet Paper Meme (2020). Covid-19 Archive. Available online at: https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/10195 (accessed June 06, 2020).

Pew Research Center (2019). Demographics of Social Media Users and Adoption in the United States. Pew Research Center; Internet, Science & Tech. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/ (accessed March 12, 2020).

Piata, A. (2016). When metaphor becomes a joke: metaphor journeys from political ads to internet memes. J. Pragmatics 106, 39–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2016.10.003

Plato (2010). “The republic,” in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd Edn. ed V. B. Leitch (New York, NY: Norton), 70.

PsyWar Leaflet Archive - 141-J-1 I CEASE RESISTANCE. (2012). PsyWar.Org. Available online at: https://www.psywar.org/product_1945PAC141J1.php (accessed June 7, 2012).

Ratkiewicz, J., Conover, M., Meiss, M., Gonçalves, B., Flammini, A., and Menczer, F. (2011). Detecting and Tracking Political Abuse in Social Media. Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research School of Informatics and Computing, 1–8.

Relman, E. (2019). Carpe Donktum, the pro-trump 'memesmith' who visited the white house, is working with the creator of the fake trump church massacre video. Business Insider. Available online at: https://www.businessinsider.com/carpe-donktum-trump-endorsed-memesmith-works-violent-fake-video-creator-2019-10 (accessed August 02, 2020).

Roose, K. (2019, July 10). Trump rolls out the red carpet for right-wing social media trolls. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/business/trump-social-media-summit.html (accessed August 02, 2020).

Ross, A. S., and Rivers, D. J. (2017). Digital cultures of political participation: internet memes and the discursive delegitimization of the 2016 U.S presidential candidates. Discourse Context Media 16, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2017.01.001

Sassure, F. D. (2010). “Course in general linguistics,” in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd Edn. ed V. B. Leitch (New York, NY: Norton), 850–866.

Schmidt, A. L., Zollo, F., Vicario, M. D., Bessi, A., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., et al. (2017). Anatomy of news consumption on facebook. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 3035–3039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1617052114

Schmulowitz, N., and Luckmann, L. D. (1945). Foreign policy by propaganda leaflets. Public Opin. Q. 9:428. doi: 10.1086/265758

Smith, A., and Anderson, M. (2019). Social Media Use 2018: Demographics and Statistics. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/ (accessed January 25, 2020).

US Army (2003). Psychological Operations Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (PSYOP) Media Subcourse PO-0816, FM 3-05.301 (FM 33-1-1) MCRP 3-40.6A. Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army. Available online at: https://fas.org/irp/doddir/army/fm3-05-301.pdf

Viala-Gaudefroy, J., and Lindaman, D. (2020). Donald Trump's 'Chinese Virus': The Politics of Naming. The Conversation. The Conversation Media Group Ltd. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/donald-trumps-chinese-virus-the-politics-of-naming-136796 (accessed May 7, 2020).

Weedon, J., Nuland, W., and Stamos, A. (2017, April 27). Information Operations and Facebook. Initial Public Release 1.0. Facebook Inc. Available online at: https://fbnewsroomus.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/facebook-and-information-operations-v1.pdf (accessed February 4, 2020).

Zhou, M., Yu, Y., and Fang, A. (2020). We are not COVID-19: Asian Americans speak out on racism. Nikkei Asian Review. Available online at: https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Coronavirus/We-are-not-COVID-19-Asian-Americans-speak-out-on-racism (accessed May 9, 2020).

Keywords: internet memes, leaflet propaganda, heuristics, social media, digital propaganda

Citation: Nieubuurt JT (2021) Internet Memes: Leaflet Propaganda of the Digital Age. Front. Commun. 5:547065. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.547065

Received: 30 March 2020; Accepted: 19 November 2020;

Published: 15 January 2021.

Edited by:

Richard G. Ellefritz, University of the Bahamas, BahamasReviewed by:

Jan Martijn Meij, Florida Gulf Coast University, United StatesJoseph M. Simpson, Texas A&M University-San Antonio, United States

Copyright © 2021 Nieubuurt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joshua Troy Nieubuurt, joshua.nieubuurt@faculty.umgc.edu

Joshua Troy Nieubuurt

Joshua Troy Nieubuurt