- Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Washington, WA, United States

- Department of Neurological Surgery, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Christopher C. Young

Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Washington, WA, United States

Department of Neurological Surgery, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_256_2019

Copyright: © 2019 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Christopher C. Young, Richard G. Ellenbogen, Jason S. Hauptman. Acute traumatic presentation of Chiari I malformation with central cord syndrome and presyrinx in an infant. 27-Dec-2019;10:253

How to cite this URL: Christopher C. Young, Richard G. Ellenbogen, Jason S. Hauptman. Acute traumatic presentation of Chiari I malformation with central cord syndrome and presyrinx in an infant. 27-Dec-2019;10:253. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9825/

Abstract

Background: Chiari I malformation (CM-I) typically presents in late childhood and early adulthood. Often these lesions are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. Patients typically present with tussive headaches and focal neurological findings, especially when associated with syringomyelia. Here, an 11-month-old child with a severely symptomatic CM-I required surgery (e.g., suboccipital craniectomy and C1/2 laminectomy) within the 1st year of life.

Case Description: An 11-month-old infant presented with acute bilateral upper extremity weakness following a ground-level fall. The magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine showed crowding at the craniocervical junction with 7 mm of cerebellar tonsillar herniation/descent, and swelling/edema of the cervical spinal cord with a presyrinx. The patient underwent an urgent suboccipital craniectomy and C1/2 laminectomy under intraoperative neuromonitoring; the motor evoked potentials in the upper and lower extremities partially recovered intraoperatively. One day postoperatively, bilateral upper extremity strength improved; 4 weeks later, he recovered full neurological function. The follow-up MR also showed complete resolution of the previously noted presyrinx.

Conclusion: Acute neurological deficits may occur in infants with CM-I who, following trauma, sustain the equivalent of a central cord syndrome. Neurosurgical evaluation with MR should prompt timely/appropriate surgical decompression (e.g., suboccipital craniectomy and C1/2 laminectomy).

Keywords: Central cord syndrome, Chiari I malformation, Posterior fossa decompression, Presyrinx, Syringomyelia

INTRODUCTION

Chiari I malformation (CM-I) is a congenital abnormality of the craniocervical junction (CCJ; frequency 0.1–0.5%). In an infant (i.e., <1 year of age) with CM-I, acute/severe neurological deterioration or even sudden death may follow even minor head/neck trauma resulting in a central cord syndrome.[

CASE REPORT

Clinical presentation

An 11-month-old boy presented with the acute onset of progressive bilateral upper extremity weakness. The previous evening, he had fallen backward, but had not sustained a loss of consciousness or shown an focal neurological deficit. However, by the next morning, he showed diminished hand movement and was unable to grasp toys. By the time he was seen in the emergency department, he was unable to raise his arms above his shoulders. On examination, the cranial nerves were normal, but both upper extremities were flaccid, and he had absent upper extremity reflexes. Notably, he retained normal motion and reflexes in both lower extremities. Laboratory studies and infectious markers were negative, for example, white blood cell of seven and ESR of eight.

Radiologic studies

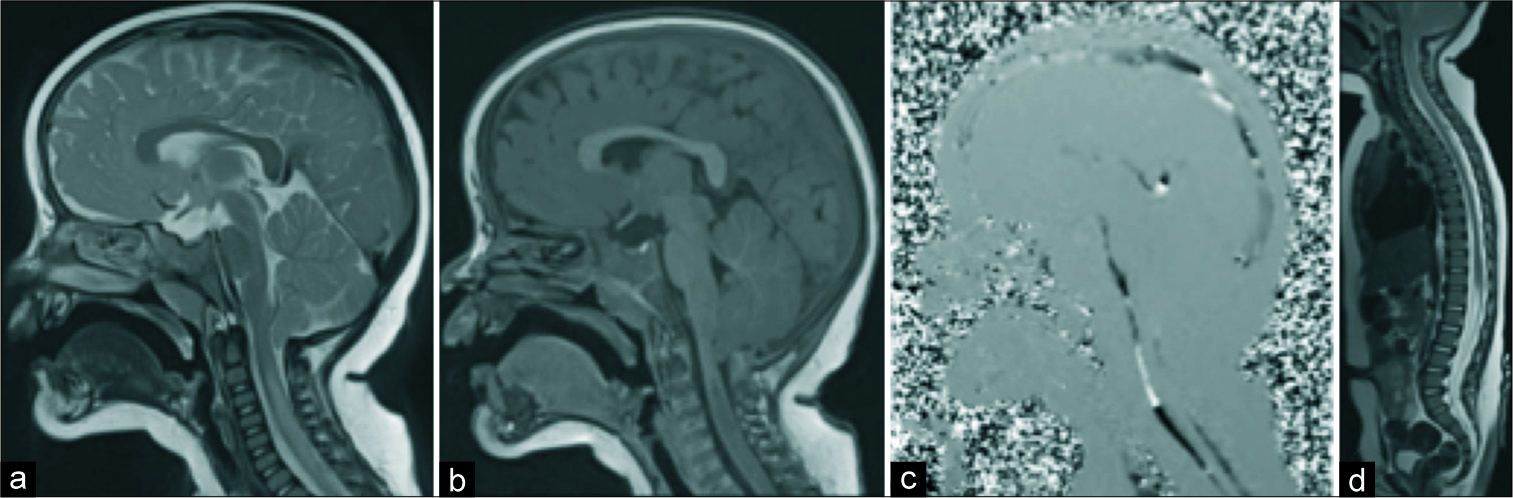

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed that the ventricles were of normal size without hydrocephalus [

Figure 1:

Chiari 1 malformation with presyrinx. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and spine demonstrate Chiari I malformation (CM-I) with tonsillar herniation 7 mm below the craniocervical junction. The cervical spinal cord is swollen from C2 to C6 with evidence of T2 (a) and T1 (b) signal elongation consistent with presyrinx. (c) Phase-contrast cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow study shows attenuation of CSF flow in the dorsal high cervical cord at the site of CM-I, which is preserved in the ventral spinal canal. (d) The remainder of the neuroaxis appeared normal without evidence of cavitation or syrinx.

Surgical management

Within 6 h of admission, after having received given 6 mg of dexamethasone, and using intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring (IONM: somatosensory evoked potentials and motor evoked potentials monitoring), the patient underwent a partial C1/2 laminectomy with suboccipital craniectomy extending to/through the foramen magnum. At surgery, there were thick fibrous bands of connective tissue that had to be dissected/excised until the superior aspect of C1 was visualized. Next, a C1 laminectomy was completed and decompression was taken laterally to the lateral masses; no duraplasty was performed. Intraoperatively, the motor evoked potentials partially recovered in both the upper and lower extremities.

Outcome

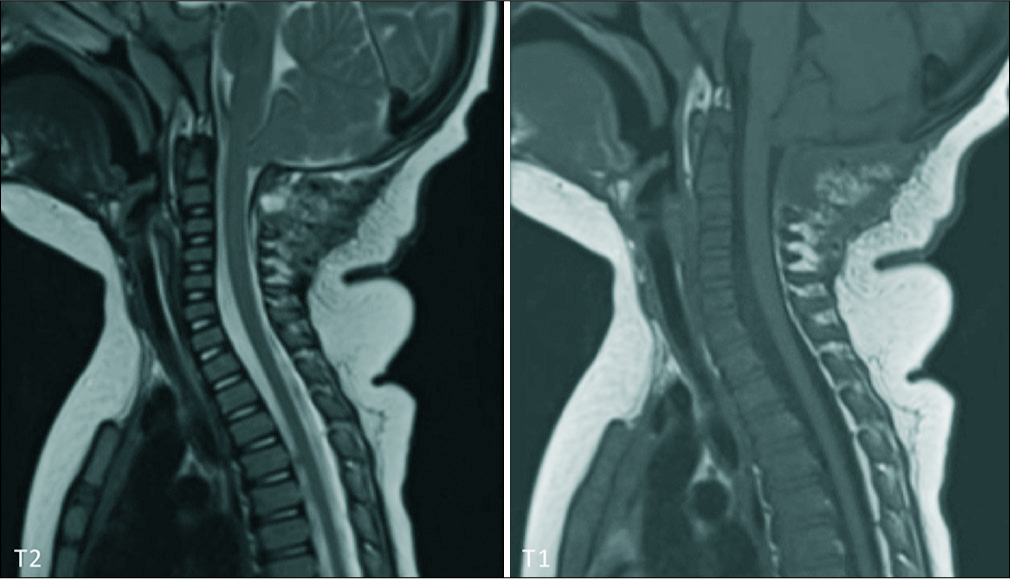

Postoperatively, the patient was extubated and was taken back to intensive care unit, moving all four extremities. He was treated with 3 mg of dexamethasone every 6 h for 3 days; this was tapered off over 5 days. On postoperative day 2, he was discharged home in a stable condition. Within 1 month, he had fully recovered. Further, the repeat MRI demonstrated total resolution of the cervical presyrinx, although the original CM-I remained stable without a change in tonsillar position [

Figure 2:

Resolution of presyrinx after surgery. One-month after bone-only posterior fossa decompression, magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine shows a similar degree of Chiari I malformation with tonsillar descent. However, the previously observed cervical spinal cord swelling and presyrinx have completely resolved. No other abnormality is observed.

DISCUSSION

The patient’s presenting symptoms are consistent with traumatic central cord syndrome, with predominantly upper extremity weakness while sparing the lower extremities. Radiographically, the patient has CM-I with crowding of the CCJ, cervical cord edema, and a presyrinx.[

Occasionally, CM-I presents with acute and severe neurological deterioration or even sudden death following minor head/neck trauma.[

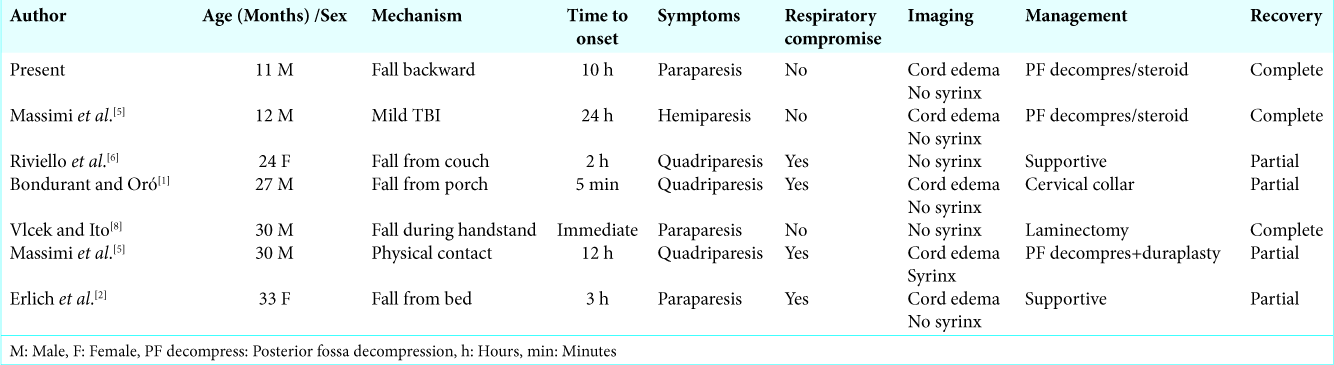

A review of the literature identified six other cases of CM-I in young children (<3 years of age) presenting with acute motor weakness following minor head/neck trauma [

CONCLUSION

CM-I usually presents with indolent symptoms and subtle neurological signs, and seldom requires surgical management in infants. However, it can occasionally present following minor trauma with acute neurological deficits. In such cases, urgent referral for neurosurgical evaluation is warranted and early decompressive surgery should be considered.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bondurant CP, Oró JJ. Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality and chiari malformation. J Neurosurg. 1993. 79: 833-8

2. Erlich V, Snow R, Heier L. Confirmation by magnetic resonance imaging of bell’s cruciate paralysis in a young child with chiari Type I malformation and minor head trauma. Neurosurgery. 1989. 25: 102-5

3. Fischbein NJ, Dillon WP, Cobbs C, Weinstein PR. The “presyrinx” state: A reversible myelopathic condition that may precede syringomyelia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999. 20: 7-20

4. Lipson AC, Ellenbogen RG, Avellino AM. Radiographic formation and progression of cervical syringomyelia in a child with untreated chiari I malformation. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2008. 44: 221-3

5. Massimi L, Della Pepa GM, Tamburrini G, Di Rocco C. Sudden onset of chiari malformation Type I in previously asymptomatic patients. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011. 8: 438-42

6. Riviello JJ, Marks HG, Faerber EN, Steg NL. Delayed cervical central cord syndrome after trivial trauma. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1990. 6: 113-7

7. Tomaszek DE, Tyson GW, Bouldin T, Hansen AR. Sudden death in a child with an occult hindbrain malformation. Ann Emerg Med. 1984. 13: 136-8

8. Vlcek BW, Ito B. Acute paraparesis secondary to arnold-chiari Type I malformation and neck hyperflexion. Ann Neurol. 1987. 21: 100-1

9. Wan MJ, Nomura H, Tator CH. Conversion to symptomatic chiari I malformation after minor head or neck trauma. Neurosurgery. 2008. 63: 748-53

10. Yarbrough CK, Powers AK, Park TS, Leonard JR, Limbrick DD, Smyth MD. Patients with chiari malformation Type I presenting with acute neurological deficits: Case series. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011. 7: 244-7