Abstract

Mammalian sterol and lipid metabolism depends on a large number of highly evolved biochemical and histological processes responsible for the absorption, distribution and steady-state anabolic/catabolic handling of these substances. Lipoproteins are complex polymolecular assemblies comprising phospholipids, cholesterol and cholesterol esters, triglycerides and a variety of apolipoproteins. The primary function of lipoproteins is to facilitate the systemic distribution of sterols and lipids. Abnormalities in lipoprotein metabolism are quite common and are attributable to a large number of genetic mutations, metabolic derangements such as insulin resistance or thyroid dysfunction, and excess availability of cholesterol and fat from dietary sources. Dyslipidaemic states facilitate endothelial dysfunction and atherogenesis. Dyslipidaemia is recognized as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in both men and women, and people of all racial and ethnic groups throughout the world. Dyslipidaemia is modifiable with dietary change and the use of medications that impact on lipid metabolism through a variety of mechanisms. Reducing atherogenic lipoprotein burden in serum is associated with significant and meaningful reductions in risk for a variety of cardiovascular endpoints, including myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke, development of peripheral arterial disease and mortality.

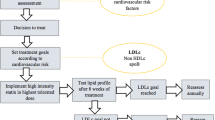

This review provides an overview on how to best position lipid-lowering drugs when attempting to normalize serum lipid profiles and reduce risk for cardiovascular disease. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are widely accepted to be the agents of choice for reducing serum levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) in both the primary and secondary prevention settings. Ezetimibe and bile acid sequestrants are both effective agents for reducing LDL-C, either used alone or in combination with statins. The statins, fibric acid derivatives (fibrates) and niacin raise high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to different extents depending upon genetic and metabolic background. Fibrates, niacin and omega-3 fish oils are efficacious therapies for reducing serum triglycerides. Combinations of these drugs are frequently required for normalizing mixed forms of dyslipidaemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Davidson MH, Toth PP. Comparative effects of lipid-lowering therapies. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2004; 47(2): 73–104

Toth PP. Low-density lipoprotein reduction in high-risk patients: how low do you go? Curr Atheroscler Rep 2004; 6(5): 348–52

Tabas I. Consequences and therapeutic implications of macrophage apoptosis in atherosclerosis: the importance of lesion stage and phagocytic efficiency. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005; 25(11): 2255–64

Tabas I, Williams KJ, Boren J. Subendothelial lipoprotein retention as the initiating process in atherosclerosis: update and therapeutic implications. Circulation 2007; 116(16): 1832–44

Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 2002; 420(6917): 868–74

Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54(23): 2129–38

Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001; 285 (19): 2486–97

Genest J, McPherson R, Frohlich J, et al. 2009 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult: 2009 recommendations. Can J Cardiol 2009; 25(10): 567–79

De Backer G, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Third Joint Task Force of European and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J 2003; 24(17): 1601–10

Boden WE, Toth PP. The evolving dyslipidemia treatment paradigm: the imperative to address residual cardiovascular disease risk beyond LDL-C. Clin Symp 2009; 59(2): 1–43

Kannel WB, Castelli WP, Gordon T. Cholesterol in the prediction of atherosclerotic disease: new perspectives based on the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med 1979; 90(1): 85–91

Stamler J, Wentworth D, Neaton JD. Is relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease continuous and graded? Findings in 356,222 primary screenees of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT). JAMA 1986; 256(20): 2823–8

Assmann G, Cullen P, Schulte H. The Munster Heart Study (PROCAM): results of follow-up at 8 years. Eur Heart J 1998; 19 Suppl. A: A2–11

Benfante R. Studies of cardiovascular disease and cause-specific mortality trends in Japanese-American men living in Hawaii and risk factor comparisons with other Japanese populations in the Pacific region: a review. Hum Biol 1992; 64(6): 791–805

Toth PP. Making a case for quantitative assessment of cardiovascular risk. J Clinical Lipidol 2007; 1: 234–41

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation 2004; 110(2): 227–39

Smith Jr SC, Allen J, Blair SN, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update. Endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [published erratum appears in Circulation 2006 Jun 6; 113 (22): e847]. Circulation 2006; 113(19): 2363–72

Toth PP. When high is low: raising low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Curr Cardiol Rep 2008; 10(6): 488–96

Armani A, Toth PP. SPARCL: the glimmer of statins for stroke risk reduction. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2007; 9(5): 347–51

Fielding CJ, Fielding PE. Molecular physiology of reverse cholesterol transport. J Lipid Res 1995; 36(2): 211–28

Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, et al. Oral D-4F causes formation of pre-beta high-density lipoprotein and improves high-density lipoprotein-mediated cholesterol efflux and reverse cholesterol transport from macrophages in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circulation 2004; 109(25): 3215–20

Cuchel M, Rader DJ. Macrophage reverse cholesterol transport: key to the regression of atherosclerosis? Circulation 2006; 113(21): 2548–55

Heinecke JW. The HDL proteome: a marker —and perhaps mediator —of coronary artery disease. J Lipid Res 2009; 50 Suppl.: S167–71

Vaisar T, Pennathur S, Green PS, et al. Shotgun proteomics implicates protease inhibition and complement activation in the antiinflammatory properties of HDL. J Clin Invest 2007; 117(3): 746–56

Castelli WP. Cholesterol and lipids in the risk of coronary artery disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Can J Cardiol 1988; 4 Suppl A: 5A–10A

Castelli WP, Doyle JT, Gordon T, et al. HDL cholesterol and other lipids in coronary heart disease: the cooperative lipoprotein phenotyping study. Circulation 1977; 55(5): 767–72

Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease: four prospective American studies. Circulation 1989; 79(1): 8–15

Chapman MJ, Assmann G, Fruchart JC, et al. Raising high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with reduction of cardiovascular risk: the role of nicotinic acid —a position paper developed by the European Consensus Panel on HDL-C. Curr Med Res Opin 2004; 20(8): 1253–68

Sarwar N, Danesh J, Eiriksdottir G, et al. Triglycerides and the risk of coronary heart disease: 10,158 incident cases among 262,525 participants in 29 western prospective studies. Circulation 2007; 115(4): 450–8

Toth PP, Dayspring TD, Pokrywka GS. Drug therapy for hypertriglyceridemia: fibrates and omega-3 fatty acids. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2009; 11(1): 71–9

Castelli WP. Epidemiology of triglycerides: a view from Framingham. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70(19): 3H–9H

Miller M, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, et al. Impact of triglyceride levels beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol after acute coronary syndrome in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51(7): 724–30

Fruchart JC. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha activation and high-density lipoprotein metabolism. Am J Cardiol 2001; 88(12A): 24N–9N

Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, et al. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA 1998; 279(20): 1615–22

Influence of pravastatin and plasma lipids on clinical events in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS). Circulation 1998; 97 (15): 1440–5

Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994; 344(8934): 1383–9

Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels: the Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998; 339 (19): 1349–57

Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364(9435): 685–96

Sever PS, Dahlof B, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial —Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003; 361(9364): 1149–58

Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med 2008; 359(21): 2195–207

Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360(9346): 1623–30

Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, et al. Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA 2006; 295(13): 1556–65

Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, et al. Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 291(9): 1071–80

Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(15): 1495–504

Cannon CP. The IDEAL cholesterol: lower is better. JAMA 2005; 294(19): 2492–4

Cannon CP, Steinberg BA, Murphy SA, et al. Metaanalysis of cardiovascular outcomes trials comparing intensive versus moderate statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48(3): 438–45

LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(14): 1425–35

Gibson CM, Pride YB, Hochberg CP, et al. Effect of intensive statin therapy on clinical outcomes among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndrome. PCI-PROVE IT: a PROVE IT-TIMI 22 (Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 22) substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54(24): 2290–5

Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective metaanalysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005; 366(9493): 1267–78

Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Efficacy of cholesterol-lowering therapy in 18,686 people with diabetes in 14 randomised trials of statins: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2008; 371(9607): 117–25

Toth PP, Davidson MH. High-dose statin therapy: benefits and safety in aggressive lipid lowering. J Fam Pract 2008; 57 (5 Suppl. High-Dose): S29–36

Toth PP, Harper CR, Jacobson TA. Clinical characterization and molecular mechanisms of statin myopathy. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2008; 6(7): 955–69

Toth PP, Cadman C. Implications of recent statin trials for primary care practice. J Clin Lipidol 2007; 1: 182–90

Jackevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV. Adherence with statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2002; 288(4): 462–7

Jones P. Beyond LDL-C: importance of triglycerides and non-HDL as an independent cardiovascular disease risk factor. J Am Acad Physician Assist 2008; 11: S7–19

The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial results. I: reduction in incidence of coronary heart disease. JAMA 1984; 251(3): 351–64

Brown G, Albers JJ, Fisher LD, et al. Regression of coronary artery disease as a result of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in men with high levels of apolipoprotein B. N Engl J Med 1990; 323(19): 1289–98

Davidson MH, Toth P, Weiss S, et al. Low-dose combination therapy with colesevelam hydrochloride and lovastatin effectively decreases low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. Clin Cardiol 2001; 24(6): 467–74

Knapp HH, Schrott H, Ma P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination simvastatin and colesevelam in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. Am J Med 2001; 110(5): 352–60

Hunninghake D, Insull Jr W, Toth P, et al. Coadministration of colesevelam hydrochloride with atorvastatin lowers LDL cholesterol additively. Atherosclerosis 2001; 158(2): 407–16

Zieve FJ, Kalin MF, Schwartz SL, et al. Results of the glucose-lowering effect of WelChol study (GLOWS): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study evaluating the effect of colesevelam hydrochloride on glycemic control in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther 2007; 29(1): 74–83

Goldberg RB, Fonseca VA, Truitt KE, et al. Efficacy and safety of colesevelam in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and inadequate glycemic control receiving insulin-based therapy. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168(14): 1531–40

Fonseca VA, Rosenstock J, Wang AC, et al. Colesevelam HCl improves glycemic control and reduces LDL cholesterol in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes on sulfonylurea-based therapy. Diabetes Care 2008; 31(8): 1479–84

Stayrook KR, Bramlett KS, Savkur RS, et al. Regulation of carbohydrate metabolism by the farnesoid X receptor. Endocrinology 2005; 146(3): 984–91

Musha H, Hayashi A, Kida K, et al. Gender difference in the level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in elderly Japanese patients with coronary artery disease. Intern Med 2006; 45(5): 241–5

Altmann SW, Davis Jr HR, Zhu LJ, et al. Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 protein is critical for intestinal cholesterol absorption. Science 2004; 303(5661): 1201–4

Kastelein JJ, Akdim F, Stroes ES, et al. Simvastatin with or without ezetimibe in familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(14): 1431–43

Bruckert E, Giral P, Tellier P. Perspectives in cholesterol-lowering therapy: the role of ezetimibe, a new selective inhibitor of intestinal cholesterol absorption. Circulation 2003; 107(25): 3124–8

Davidson MH, McGarry T, Bettis R, et al. Ezetimibe coadministered with simvastatin in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 40(12): 2125–34

Jackevicius CA, Tu JV, Ross JS, et al. Use of ezetimibe in the United States and Canada. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(17): 1819–28

Ballantyne CM, Abate N, Yuan Z, et al. Dose-comparison study of the combination of ezetimibe and simvastatin (Vytorin) versus atorvastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia: the Vytorin Versus Atorvastatin (VYVA) study. Am Heart J 2005; 149(3): 464–73

Brown BG, Taylor AJ. Does ENHANCE diminish confidence in lowering LDL or in ezetimibe? N Engl J Med 2008; 358(14): 1504–7

Toth PP. Subclinical atherosclerosis: what it is, what it means and what we can do about it. Int J Clin Pract 2008; 62(8): 1246

Toth PP, Maki K. A commentary on the implications of the ENHANCE (Ezetimibe and Simvastatin in Hypercholesterolemia Enhances Atherosclerosis Regression) trial: should ezetimibe move to the “back of the line” as a therapy for dyslipidemia? J Clin Lipidol 2008; 2(5): 313–7

Rossebo AB, Pedersen TR, Boman K, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with simvastatin and ezetimibe in aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2008; 359(13): 1343–56

Cannon CP, Giugliano RP, Blazing MA, et al. Rationale and design of IMPROVE-IT (IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial): comparison of ezetimbe/simvastatin versus simvastatin monotherapy on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2008; 156(5): 826–32

Manninen V, Elo MO, Frick MH, et al. Lipid alterations and decline in the incidence of coronary heart disease in the Helsinki Heart Study. JAMA 1988; 260(5): 641–51

Robins SJ, Collins D, Wittes JT, et al. Relation of gemfibrozil treatment and lipid levels with major coronary events: VA-HIT: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 285(12): 1585–91

Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, et al. Diabetes, plasma insulin, and cardiovascular disease: subgroup analysis from the Department of Veterans Affairs high-density lipoprotein intervention trial (VA-HIT). Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(22): 2597–604

Secondary prevention by raising HDL cholesterol and reducing triglycerides in patients with coronary artery disease: the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention (BIP) study. Circulation 2000; 102 (1): 21–7

Keech A, Simes RJ, Barter P, et al. Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 366(9500): 1849–61

Prueksaritanont T, Zhao JJ, Ma B, et al. Mechanistic studies on metabolic interactions between gemfibrozil and statins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 301(3): 1042–51

Prueksaritanont T, Subramanian R, Fang X, et al. Glucuronidation of statins in animals and humans: a novel mechanism of statin lactonization. Drug Metab Dispos 2002; 30(5): 505–12

ACCORD Study Group, Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2010; 362(17): 1563–74

Canner PL, Berge KG, Wenger NK, et al. Fifteen year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol 1986; 8(6): 1245–55

Lamon-Fava S, Diffenderfer MR, Barrett PH, et al. Extended-release niacin alters the metabolism of plasma apolipoprotein (Apo) A-I and ApoB-containing lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008; 28(9): 1672–8

Kamanna VS, Kashyap ML. Nicotinic acid (niacin) receptor agonists: will they be useful therapeutic agents? Am J Cardiol 2007; 100(11 A): S53–61

Tunaru S, Kero J, Schaub A, et al. PUMA-G and HM74 are receptors for nicotinic acid and mediate its anti-lipolytic effect. Nat Med 2003; 9(3): 352–5

Brown BG, Zhao XQ, Chait A, et al. Simvastatin and niacin, antioxidant vitamins, or the combination for the prevention of coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(22): 1583–92

Taylor AJ, Sullenberger LE, Lee HJ, et al. Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol (ARBITER) 2: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of extended-release niacin on atherosclerosis progression in secondary prevention patients treated with statins. Circulation 2004; 110(23): 3512–7

Taylor AJ, Lee HJ, Sullenberger LE. The effect of 24 months of combination statin and extended-release niacin on carotid intima-media thickness: ARBITER 3. Curr Med Res Opin 2006; 22(11): 2243–50

Taylor AJ, Villines TC, Stanek EJ, et al. Extended-release niacin or ezetimibe and carotid intima-media thickness. N Engl J Med 2009; 361(22): 2113–22

Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: American Heart Association scientific statement. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004; 24(3): e29–50

Guyton JR, Bays HE. Safety considerations with niacin therapy. Am J Cardiol 2007; 99(6A): 22–31C

Birjmohun RS, Kastelein JJ, Poldermans D, et al. Safety and tolerability of prolonged-release nicotinic acid in statin-treated patients. Curr Med Res Opin 2007; 23(7): 1707–13

Cefali EA, Simmons PD, Stanek EJ, et al. Improved control of niacin-induced flushing using an optimized once-daily, extended-release niacin formulation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2006; 44(12): 633–40

Cefali EA, Simmons PD, Stanek EJ, et al. Aspirin reduces cutaneous flushing after administration of an optimized extended-release niacin formulation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007; 45(2): 78–88

Rubenfire M; Impact of Medical Subspecialty on Patient Compliance to Treatment Study Group. Safety and compliance with once-daily niacin extended-release/lovastatin as initial therapy in the Impact of Medical Subspecialty on Patient Compliance to Treatment (IMPACT) study. Am J Cardiol 2004; 94(3): 306–11

Oberwittler H, Baccara-Dinet M. Clinical evidence for use of acetyl salicylic acid in control of flushing related to nicotinic acid treatment. Int J Clin Pract 2006; 60(6): 707–15

Maccubbin D, Koren MJ, Davidson M, et al. Flushing profile of extended-release niacin/laropiprant versus gradually titrated niacin extended-release in patients with dyslipidemia with and without ischemic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2009; 104(1): 74–81

Paolini JF, Mitchel YB, Reyes R, et al. Effects of laropiprant on nicotinic acid-induced flushing in patients with dyslipidemia. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101(5): 625–30

AIM-HIGH Cholesterol Management Program. Working toward a healthy heart [online]. Available from URL: http://www.aimhigh-heart.com/background.shtml [Accessed 2010 May 27]

Harper CR, Jacobson TA. Usefulness of omega-3 fatty acids and the prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2005; 96(11): 1521–9

Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ; American Heart Association, Nutrition Committee. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. [published erratum appears in Circulation 2003 Jan 28; 107 (3): 512]. Circulation 2002; 106(21): 2747–57

Lee JH, O’Keefe JH, Lavie CJ, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids for cardioprotection. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83(3): 324–32

Marchioli R, Barzi F, Bomba E, et al. Early protection against sudden death by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids after myocardial infarction: time-course analysis of the results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI)-Prevenzione. Circulation 2002; 105(16): 1897–903

Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, et al. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet 2007; 369(9567): 1090–8

Lovaza® prescribing information. Research Triangle Park (NC): GlaxoSmithKline, 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_lovaza.pdf [Accessed 2010 May 27]

Goldberg RB, Kendall DM, Deeg MA, et al. A comparison of lipid and glycemic effects of pioglitazone and rosiglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care 2005; 28(7): 1547–54

Acknowledgements

The author received no writing assistance or any financial remuneration of any kind during the preparation of this manuscript. Dr Toth is a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Kowa and Merck and Co.; he is a member of the Speakers Bureau for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Kowa, Merck and Co., Pfizer and Takeda.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toth, P.P. Drug Treatment of Hyperlipidaemia. Drugs 70, 1363–1379 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2165/10898610-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/10898610-000000000-00000