-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paul J. Hampel, Timothy G. Call, Kari G. Rabe, Wei Ding, Eli Muchtar, Saad S. Kenderian, Yucai Wang, Jose F. Leis, Thomas E. Witzig, Amber B. Koehler, Amie L. Fonder, Susan M. Schwager, Daniel L. Van Dyke, Esteban Braggio, Susan L. Slager, Neil E. Kay, Sameer A. Parikh, Disease Flare During Temporary Interruption of Ibrutinib Therapy in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, The Oncologist, Volume 25, Issue 11, November 2020, Pages 974–980, https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0388

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Approximately 25% of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) experience a flare of disease following ibrutinib discontinuation. A critical question is whether this phenomenon may also occur when ibrutinib is temporarily held. This study aimed to determine the frequency and characteristics of disease flares in this setting and assess risk factors and clinical outcomes.

We identified all patients with CLL seen at Mayo Clinic between October 2012 and March 2019 who received ibrutinib. Temporary interruptions in treatment and associated clinical findings were ascertained.

Among the 372 patients identified, 143 (38%) had at least one temporary interruption (median 1 hold, range 1–7 holds) in treatment. The median duration of interruption was 8 days (range 1–59 days) and the most common indication was periprocedural. Among the 143 patients with ≥1 hold, an associated disease flare was seen in 35 (25%) patients: mild (constitutional symptoms only) in 21 patients and severe (constitutional symptoms with exam/radiographic findings or laboratory changes) in 14 patients. Disease flare resolved with resuming ibrutinib in all patients. Predictive factors of disease flare included progressive disease at time of hold and ≥ 24 months of ibrutinib exposure. The occurrence of disease flare with an ibrutinib hold was associated with shorter event‐free survival (hazard ratio 2.3; 95% confidence interval 1.3–4.1; p = .007) but not overall survival.

Temporary interruptions in ibrutinib treatment of patients with CLL are common, and one quarter of patients who held ibrutinib in this study experienced a disease flare. Resolution with resuming ibrutinib underscores the importance of awareness of this phenomenon for optimal management.

Ibrutinib is a very effective treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) but needs to be taken continuously. Side effects, such as increased bleeding risk with procedures, require temporary interruptions in this continuous treatment. Rapid CLL progression following ibrutinib discontinuation has been increasingly recognized. This study demonstrates that similar flares in disease signs or symptoms may occur during ibrutinib holds as well. Importantly, management with restarting ibrutinib led to quick clinical improvement. Awareness of this phenomenon among clinicians is critical to avoid associated patient morbidity and premature cessation of effective treatment with ibrutinib if the flare is misidentified as true progression of disease.

Introduction

The treatment landscape for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has seen sweeping changes with the emergence of B‐cell receptor signal pathway antagonists and BCL‐2 antagonists. The first‐in‐class Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, ibrutinib, was an initial targeted agent to gain approval for all lines of therapy. Extended follow‐up from the early phase Ib/II trial demonstrates the long‐term benefit from ibrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL with estimated 7‐year progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates of 32% and 52%, respectively [1]. Results from the pivotal phase III RESONATE trial in relapsed/refractory CLL further established this durable benefit, with median PFS and OS reported at 44 months and 68 months, respectively, in the final analysis [2]. Similarly evident in these findings is the corresponding need for extended treatment duration, delivered in a continuous administration schedule until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Unfortunately, therapy with ibrutinib is associated with various side effects, including bleeding and hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities, as well as drug–drug interactions, that may necessitate dose modifications or interruption of treatment [3–5]. Anecdotal reports of disease flare when ibrutinib is held in patients with CLL have been published [6]. This phenomenon has also been observed with temporary suspension of ibrutinib therapy in patients with Waldenström's macroglobulinemia, resolving with restarting ibrutinib [7, 8]. We reviewed the electronic health records of all patients treated with ibrutinib for CLL at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, to determine whether disease flares occur in the setting of temporary interruption of ibrutinib therapy.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The Mayo Clinic CLL Database maintains a robustly archived registry of all patients with CLL seen in the Division of Hematology at Mayo Clinic since 1995 who consented for their records to be used for research purposes. All patients who received ibrutinib therapy from October 2012 to March 2019 were identified and a detailed review of the electronic medical record was conducted to determine (a) if they held ibrutinib at any point during the course of their disease; (b) reasons for hold; (c) duration of hold; and (d) number of times ibrutinib was held. Holds in treatment required the intent of temporary duration; patients who planned permanent discontinuations followed by restarting ibrutinib were excluded. Patients who were treated with ibrutinib elsewhere before being seen at Mayo Clinic or those who did not seek continued care at Mayo Clinic for management of CLL were excluded. Temporary interruptions in ibrutinib therapy were carried out according to clinical trial specifications (if patients were treated on a clinical trial) or according to the package instructions (for patients receiving therapy in routine clinical practice) [9]. The following were then assessed for all patients during the time of interruption: (a) new or worsening disease‐related or constitutional symptoms; (b) exam or radiographic evidence of worsening lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly; and (c) laboratory changes (increased absolute lymphocyte count [ALC] to double the prehold value and at least >5.0 × 109/L or lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] increased by 50% of prehold value and at least greater than the upper limit of normal [222 U/L]). Flare of disease was defined as mild if symptoms alone were present and severe if two of these three changes were found. If a particular symptom was the indication for holding ibrutinib for an individual patient, then it was excluded from consideration as a potential symptom of disease flare during that temporary interruption. Responses were assessed for all patients at the time of ibrutinib hold according to 2018 International Workshop on CLL guidelines [10], with the addition of clinical complete remission (CR) defined as clinical and hematologic parameters compatible with a CR but confirmatory bone marrow biopsy not performed. Testing for BTK and PLCG2 mutation was performed as part of routine clinical practice at either NeoGenomics Laboratories or The Ohio State University [11, 12].

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics and reasons for temporary interruptions in those who held ibrutinib were summarized. We used logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and evaluated factors associated with disease flare at first hold and in all holds. The effect of disease flare on event‐free survival (EFS) and OS were analyzed as a time‐dependent factor in age‐ and sex‐adjusted Cox regression models. EFS and OS were calculated from the start of ibrutinib. Events for EFS analysis were defined as the occurrence of progression of CLL or Richter's transformation, change in line of CLL therapy following first hold date, or death. Patients who had progression of disease at the time of ibrutinib hold were excluded from EFS analyses. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Overall Cohort (n = 372), Patient Demographics at Ibrutinib Initiation

A total of 372 patients were treated with ibrutinib during the study period. Median age was 68 years, and 259 patients (70%) were male. IGHV was unmutated in 233 patients (75%), TP53 disruption (del(17p) or TP53 somatic mutation) was present in 68 patients (20%), 113 patients (30%) were treated in the frontline setting, and 315 patients (85%) were treated outside the context of a clinical trial. Median duration of ibrutinib treatment was 35 months. See Table 1 for additional baseline characteristics.

Patient characteristics at initiation of ibrutinib (n = 372)

| Parameter . | n (%) or median (range) . |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 68 (35–94) |

| Male | 259 (70) |

| Treated on clinical trial | 57 (15) |

| Frontline therapy | 113 (30) |

| Rai stage | |

| 0 | 42 (13) |

| I–II | 115 (37) |

| III–IV | 158 (50) |

| Missing | 57 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count, ×109/L | 38.3 (0.1–436.4) |

| Missing | 16 |

| IGHV mutation status | |

| Unmutated | 233 (75) |

| Missing | 61 |

| Fluorescence in situ hybridization | |

| Normal | 55 (16) |

| Other | 5 (2) |

| 13q‐ | 96 (29) |

| Trisomy 12 | 58 (17) |

| 11q‐ | 68 (20) |

| 17p‐ | 53 (16) |

| Missing | 37 |

| TP53 disruption (del17p and/or TP53 mutation) | |

| Abnormal | 68 (20) |

| Missing | 34 |

| Parameter . | n (%) or median (range) . |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 68 (35–94) |

| Male | 259 (70) |

| Treated on clinical trial | 57 (15) |

| Frontline therapy | 113 (30) |

| Rai stage | |

| 0 | 42 (13) |

| I–II | 115 (37) |

| III–IV | 158 (50) |

| Missing | 57 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count, ×109/L | 38.3 (0.1–436.4) |

| Missing | 16 |

| IGHV mutation status | |

| Unmutated | 233 (75) |

| Missing | 61 |

| Fluorescence in situ hybridization | |

| Normal | 55 (16) |

| Other | 5 (2) |

| 13q‐ | 96 (29) |

| Trisomy 12 | 58 (17) |

| 11q‐ | 68 (20) |

| 17p‐ | 53 (16) |

| Missing | 37 |

| TP53 disruption (del17p and/or TP53 mutation) | |

| Abnormal | 68 (20) |

| Missing | 34 |

Patient characteristics at initiation of ibrutinib (n = 372)

| Parameter . | n (%) or median (range) . |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 68 (35–94) |

| Male | 259 (70) |

| Treated on clinical trial | 57 (15) |

| Frontline therapy | 113 (30) |

| Rai stage | |

| 0 | 42 (13) |

| I–II | 115 (37) |

| III–IV | 158 (50) |

| Missing | 57 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count, ×109/L | 38.3 (0.1–436.4) |

| Missing | 16 |

| IGHV mutation status | |

| Unmutated | 233 (75) |

| Missing | 61 |

| Fluorescence in situ hybridization | |

| Normal | 55 (16) |

| Other | 5 (2) |

| 13q‐ | 96 (29) |

| Trisomy 12 | 58 (17) |

| 11q‐ | 68 (20) |

| 17p‐ | 53 (16) |

| Missing | 37 |

| TP53 disruption (del17p and/or TP53 mutation) | |

| Abnormal | 68 (20) |

| Missing | 34 |

| Parameter . | n (%) or median (range) . |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 68 (35–94) |

| Male | 259 (70) |

| Treated on clinical trial | 57 (15) |

| Frontline therapy | 113 (30) |

| Rai stage | |

| 0 | 42 (13) |

| I–II | 115 (37) |

| III–IV | 158 (50) |

| Missing | 57 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count, ×109/L | 38.3 (0.1–436.4) |

| Missing | 16 |

| IGHV mutation status | |

| Unmutated | 233 (75) |

| Missing | 61 |

| Fluorescence in situ hybridization | |

| Normal | 55 (16) |

| Other | 5 (2) |

| 13q‐ | 96 (29) |

| Trisomy 12 | 58 (17) |

| 11q‐ | 68 (20) |

| 17p‐ | 53 (16) |

| Missing | 37 |

| TP53 disruption (del17p and/or TP53 mutation) | |

| Abnormal | 68 (20) |

| Missing | 34 |

Temporary Interruptions

Among these 372 patients, 143 (38%) had at least one temporary interruption of ibrutinib treatment (median 1 hold, range 1–7 holds) during the course of treatment. A total of 245 holds were recorded; median duration of interruption was 8 days (range 1–59 days). The most common indications by number of holds included periprocedural (n = 97), bleeding (n = 26), neutropenia (n = 23), and myalgias/arthralgias (n = 20); see Table 2 for listing of indications for all holds. At the time of hold (n = 245), the following response assessments were observed: CR/CR with incomplete marrow recovery/clinical CR (n = 44), partial remission (n = 191), and progressive disease (n = 10).

Indications for temporary interruptions in ibrutinib treatment, presented according to the total number of holds (n = 245) in 143 patients

| Indication . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Periprocedural (n = 97) | |

| Elective procedures | 92 (38) |

| Urgent procedures | 5 (2) |

Nonhematologic toxicity (n = 122) | |

| Minor bleeding | 26 (11) |

| Myalgia | 20 (8) |

| Infection | 18 (7) |

| Rash | 13 (5) |

| Atrial arrhythmia | 13 (5) |

| Diarrhea | 8 (3) |

| Othera | 24 (10) |

Hematologic toxicity (n = 26) | |

| Neutropenia | 23 (9) |

| Autoimmune cytopenia | 3 (1) |

| Indication . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Periprocedural (n = 97) | |

| Elective procedures | 92 (38) |

| Urgent procedures | 5 (2) |

Nonhematologic toxicity (n = 122) | |

| Minor bleeding | 26 (11) |

| Myalgia | 20 (8) |

| Infection | 18 (7) |

| Rash | 13 (5) |

| Atrial arrhythmia | 13 (5) |

| Diarrhea | 8 (3) |

| Othera | 24 (10) |

Hematologic toxicity (n = 26) | |

| Neutropenia | 23 (9) |

| Autoimmune cytopenia | 3 (1) |

aOther includes a number of indications ranging occurring 1–3 times, including insurance issues (n = 3), dyspnea (n = 3), not documented (n = 3), transient ischemic event or ischemic cerebrovascular accident (n = 2), electrolyte abnormalities (n = 2), transaminitis (n = 1), patient preference (n = 1), medication interaction (n = 1), headache (n = 1), dizziness (n = 1), anosmia (n = 1), Raynaud's phenomenon (n = 1), weakness (n = 1), fatigue (n = 1), weight loss (n = 1), and concern for allergy (n = 1).

Indications for temporary interruptions in ibrutinib treatment, presented according to the total number of holds (n = 245) in 143 patients

| Indication . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Periprocedural (n = 97) | |

| Elective procedures | 92 (38) |

| Urgent procedures | 5 (2) |

Nonhematologic toxicity (n = 122) | |

| Minor bleeding | 26 (11) |

| Myalgia | 20 (8) |

| Infection | 18 (7) |

| Rash | 13 (5) |

| Atrial arrhythmia | 13 (5) |

| Diarrhea | 8 (3) |

| Othera | 24 (10) |

Hematologic toxicity (n = 26) | |

| Neutropenia | 23 (9) |

| Autoimmune cytopenia | 3 (1) |

| Indication . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Periprocedural (n = 97) | |

| Elective procedures | 92 (38) |

| Urgent procedures | 5 (2) |

Nonhematologic toxicity (n = 122) | |

| Minor bleeding | 26 (11) |

| Myalgia | 20 (8) |

| Infection | 18 (7) |

| Rash | 13 (5) |

| Atrial arrhythmia | 13 (5) |

| Diarrhea | 8 (3) |

| Othera | 24 (10) |

Hematologic toxicity (n = 26) | |

| Neutropenia | 23 (9) |

| Autoimmune cytopenia | 3 (1) |

aOther includes a number of indications ranging occurring 1–3 times, including insurance issues (n = 3), dyspnea (n = 3), not documented (n = 3), transient ischemic event or ischemic cerebrovascular accident (n = 2), electrolyte abnormalities (n = 2), transaminitis (n = 1), patient preference (n = 1), medication interaction (n = 1), headache (n = 1), dizziness (n = 1), anosmia (n = 1), Raynaud's phenomenon (n = 1), weakness (n = 1), fatigue (n = 1), weight loss (n = 1), and concern for allergy (n = 1).

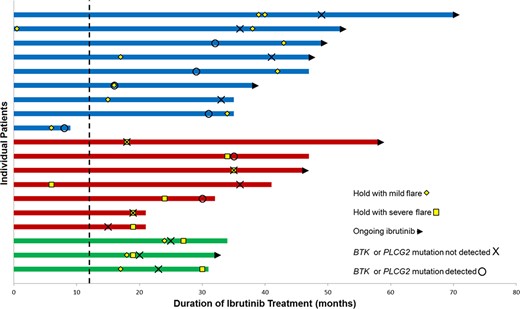

Of 245 total holds, disease flare was observed during 41 holds (17%) among 35 unique patients (25% of 143 patients); 6 patients experienced this phenomenon twice with different dose interruptions. The median duration of ibrutinib interruption among all 41 holds associated with a disease flare was 7 days (range 2–47 days) and was not different between mild flares (median 7 days, range 2–47 days) and severe flares (median 8 days, range 3–31 days). Clinically ascertained mutational testing of BTK and PLCG2 genes was performed in 19 of the 35 patients who experienced a disease flare (mutation detected n = 7, mutation not detected n = 12; Fig. 1). Indications for the 41 holds associated with a disease flare are displayed in Figure 2.

Timeline of ibrutinib treatment in unique patients (n = 19) with disease flare and BTK resistance mutational testing performed. Patients with only mild disease flare events (blue) compared with patients with severe disease flare events only (red) and patients with both (green) who had clinically ascertained mutational testing of BTK and PLCG2 genes performed during their treatment course. Eleven patients had unmutated resistance genes at the time of flare or later; six patients had mutated resistance genes at the time of flare or earlier. One patient had an unmutated result 6 months prior to their disease flare, and another one patient had a mutated result 5 months after their flare event. Dashed line indicating 12‐month mark.

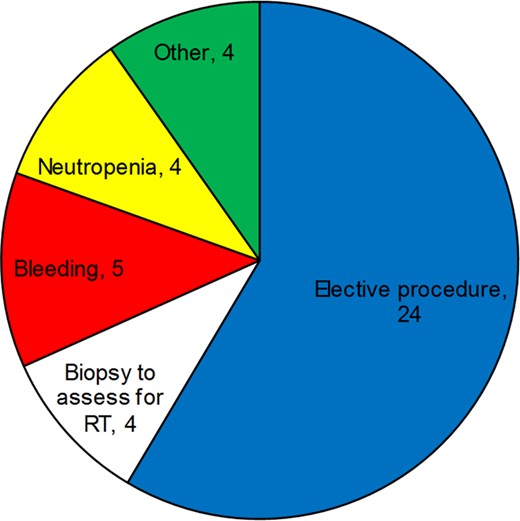

Indications for the 41 temporary interruptions in ibrutinib associated with a disease flare.

Abbreviation: RT, Richter's transformation.

Indication for Hold and Disease Flare

Among the 97 ibrutinib holds for a procedure, 28 holds had an associated disease flare (mild [n = 18], severe [n = 10]). The procedures associated with disease flare included both elective procedures (n = 24) and biopsies performed to assess for Richter's transformation (n = 4; mild [n = 1], severe [n = 3]). Two of the four patients evaluated for Richter's transformation were found to have histologic transformation (vs. CLL alone in the other two patients). Their disease grew rapidly when ibrutinib was held and then subsequently returned to prebiopsy disease level or better when resuming ibrutinib and in the absence of definitive treatment of Richter's transformation. Among the 148 nonperiprocedural holds, 13 were associated with disease flare (mild [n = 9], severe [n = 4]). Minor bleeding (n = 5; mild [n = 3], severe [n = 2]) and neutropenia (n = 4; mild [n = 3], severe [n = 1]) were the most common indications. Other toxicity indications for holds associated with mild disease flare included arthralgia (n = 1), ischemic stroke (n = 1), and anosmia (n = 1), as well as transient ischemic attack (n = 1) with severe disease flare. Among 10 patients with progressive disease at the time of hold, 5 of 7 patients with procedure‐related holds (mild [n = 2], severe [n = 3]) and 0 of 3 patients with nonprocedure holds experienced a disease flare.

Clinical Findings and Management in Patients with Disease Flare

Twenty‐seven holds (11% of 245 holds) in 21 patients (15% of 143 patients) involved a mild disease flare. The symptoms of disease flare in these cases involved fatigue/malaise (n = 13), fever (n = 13), painful lymph nodes (n = 7), night sweats (n = 2), and other (n = 3; body aches [n = 1], headache [n = 1], abdominal pain [n = 1]); 10 holds were associated with multiple symptoms. Management involved restarting ibrutinib in all 27 holds, as well as methylprednisolone in one patient.

Fourteen holds (6% of 245 holds) in 14 unique patients (10% of 143 patients) had an associated severe disease flare. Qualifying findings included new or worsening symptoms (n = 13), new or worsening lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly (n = 12), and ALC and/or LDH increase (n = 9). Of the 13 patients with new or worsening symptoms, symptoms included fatigue/malaise (n = 9), fever (n = 3), night sweats (n = 3), painful lymph nodes (n = 2), myalgias (n = 2), nausea (n = 1), dyspnea (n = 1); 6 patients had multiple symptoms. All 14 patients were managed with restarting ibrutinib with resolution of the signs and symptoms associated with the acute disease flare; no deaths occurred as a result of the flare. High‐dose methylprednisolone (n = 6) and rituximab (n = 3) were used as adjuncts in a subset of patients.

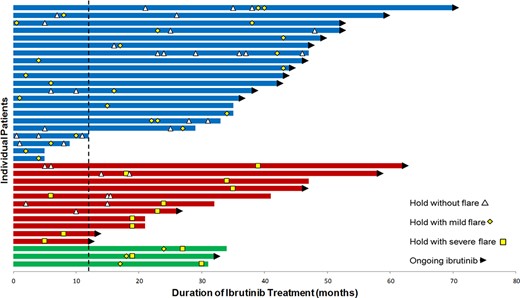

Factors Predictive of Disease Flare

Among the 41 holds with an associated disease flare, clinical response at the time of hold showed 4 (10%) clinical complete remission (4 mild flare, 0 severe flare), 32 (78%) partial remission (21 mild flare, 11 severe flare), and 5 (12%) progressive disease (2 mild flare, 3 severe flare). We analyzed baseline factors at time of ibrutinib start, including sex, age, del17p, TP53 disruption, and IGHV mutation status, time on ibrutinib prior to hold, prior therapy (relapsed/refractory vs. frontline), and response at the time of hold with respect to risk of flare. Predictors of flare at any hold were progressive disease at the time of hold OR 5.5 (95% CI 1.5–20.1; p = .009) and longer continuous ibrutinib exposure (months) OR 1.05 (95% CI 1.02–1.08; p = .0003). When excluding holds occurring with progressive disease, ≥24 months of ibrutinib exposure was predictive of disease flare (OR 2.5; 95% CI 1.2–5.2; p = .02) among the 235 holds. The median time from start of ibrutinib to start of a first hold associated with disease flare was 35 months; median 43 months for mild episodes and median not reached for severe episodes. See Figure 3 for the timing of disease flares in relation to ibrutinib treatment for individual patients.

Timeline of ibrutinib treatment in relation to temporary interruptions and disease flares among unique patients (n = 35) who experienced at least one disease flare. Twenty‐one patients with only a mild disease flare (blue), 11 patients with only a severe disease flare (red), and 3 patients with both (green). Disease flare during temporary interruption occurred in the setting of both initial holds and subsequent holds, as well as within 12 months of treatment (vertical dashed line) and later in the treatment course. Altogether, 6 of the 13 patients (46%) with subsequent treatment interruption after a disease flare of any severity experienced a recurrent flare. Dashed line indicating 12‐month mark.

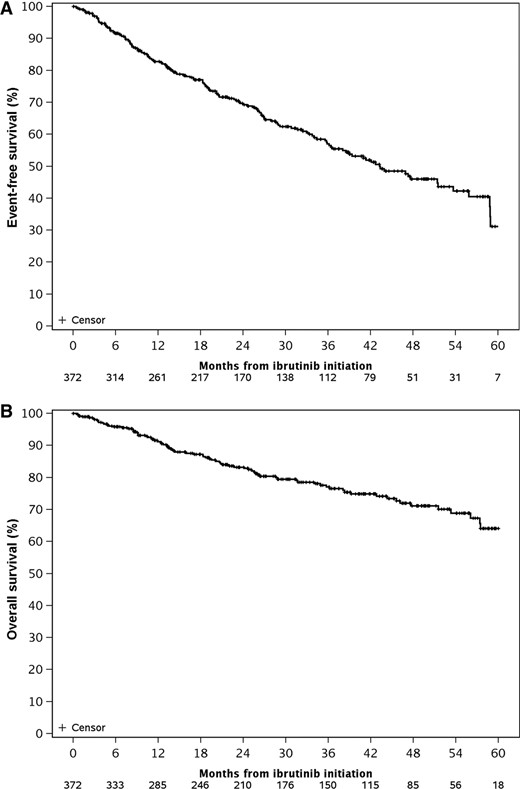

Patient Outcomes

Among all 372 patients, after a median follow‐up of 37 months, the estimated median EFS was 43 months (Fig. 4A), and the estimated median OS was 71 months (Fig. 4B). Of the 143 patients who had at least one hold, the occurrence of disease flare during interruption of ibrutinib therapy was associated with shorter EFS (hazard ratio [HR]: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.3–4.1; p = .007) but did not affect OS (HR: 1.2; 95% CI: 0.6–2.4; p = .57). Disease flare at first hold (23 of 143 patients) was predictive of time to next therapy (HR: 2.1; 95% CI 1.1–4.4; p = .04) on unadjusted analysis. Disease flare also led to either acute hospitalization or prolongation of an ongoing hospitalization (n = 12) or emergency department evaluation (n = 2) in 14/41 (34%) of holds.

Event‐free survival and overall survival for the entire cohort of 372 patients from start of ibrutinib.

Discussion

Ibrutinib is effective therapy, demonstrating durable responses in both the relapsed/refractory setting [1] and more recently outperforming standard‐of‐care chemoimmunotherapy regimens in the frontline setting [13, 14]. For many patients receiving ibrutinib, discontinuation owing to either progression or toxicity [15, 16] remains an eventuality that carries with it the risk of disease flare [17]. Furthermore, the adverse effect profile of ibrutinib along with continuous administration leads to necessary interruptions in treatment. In our study cohort of 372 patients with a median duration of treatment of 35 months, nearly 40% of patients required at least one hold during their treatment course. An associated disease flare was seen with the temporary interruption of therapy in one quarter of patients, leading to immediate morbidity requiring hospitalization in some cases, as well as inferior EFS.

Multiple studies have described dose reductions in approximately 15%–30% of ibrutinib‐treated patients [2–4, 18]. Across varied patient cohorts evaluating dose reductions, consistent findings of no significant differences in PFS or OS have been reported [3, 18–22]. Temporary interruptions in treatment appear more frequent, with estimates ranging from 35% of patients in clinical practice [4] to 65% of those treated on clinical trials [2]. The literature regarding the impact of these holds on clinical outcomes has been mixed. Data from the RESONATE trial suggested shorter PFS among patients with an interruption of ≥8 days [23], and a real‐world cohort from the U.K. CLL Forum reported inferior OS with first‐year temporary breaks in ibrutinib treatment >14 days [19]. However, other clinical trial [3] and routine clinical practice cohorts [20, 22] have found no evidence of an association between temporary interruptions and PFS and OS. Although the evidence of the impact of temporary interruptions is mixed, studies are lacking as to the impact of a disease flare during these holds. In the current study, disease flares were associated with inferior EFS (HR: 2.3; p = .007) among patients with at least one hold. Our study also highlights the potential for increased morbidity for these patients, partially depicted by the one third of patients requiring emergency department evaluation, acute hospitalization, or prolongation of an ongoing hospitalization.

Not unexpectedly, patients in the current study with progressive disease at the time of ibrutinib hold were more likely to have an associated disease flare, which occurred in 5 out of 10 patients ranging from mild (n = 2) to severe (n = 3). This correlates with the propensity for rapid progression of disease that can be observed at ibrutinib discontinuation [17, 24]. Because the majority of holds (including 96% of the 245 in this study) and majority of disease flare events (88% of the 41 holds in this study) occur in patients without signs of progression, identifying predictive factors in this scenario is particularly important. Longer ibrutinib exposure predicted a statistically significant increased risk of disease flare; however, the clinically significant finding is the potential for flares to occur at any time in the treatment course. Whether the increased risk with longer exposure is more reflective of subclinical resistance and a disease state more primed for flare or simply the increased time at risk for an event is uncertain. Although disease flares occurred at a numerically higher rate with periprocedural interruptions in therapy, caution is necessary when interpreting this finding because of the heterogeneity of nonprocedural hold indications.

Practical aspects of management include resuming ibrutinib when able as the cornerstone of ameliorating flares once one has occurred. In addition, corticosteroids are a rational option to consider in either an anticipatory/preventive or reactive management of disease flare with ibrutinib interruption. Suppression of proinflammatory cytokines may stave off the associated constitutional symptoms, while disruption of the CLL B‐cell homing mechanisms may also factor into their effect [25]. Limiting the number of days for which ibrutinib is held is another consideration. The package insert recommendation is to withhold treatment pre‐ and postprocedurally 3–7 days [9]. However, if ibrutinib is held for a colonoscopy but no polypectomy is performed, then resuming ibrutinib immediately or the day following the procedure could be appropriate. Although the median duration of interruption was 7 days among the 41 patients who experienced a disease flare in our study, these events were observed across the spectrum of hold duration (range 2–47 days). Importantly, interruptions in therapy may obscure an accurate assessment of response in that instant and clinical advertence for sustained progression following resuming ibrutinib should serve as confirmation when possible. This approach may help avoid a premature change in treatment regimen.

Transient lymph node enlargement, often coinciding with drops in ALC, had been observed even later in the course of patients responding well to ibrutinib in an intermittent dosing protocol [26]. This observation and the infrequent achievement of minimal residual disease with ibrutinib monotherapy [14, 27] make evident the ability to suppress but not eradicate CLL in most patients. Disease flare may then intuitively represent an exaggerated example of this phenomenon in CLL clones possessing an ibrutinib‐addicted phenotype. Resistance mutations in BTK or PLCG2 leading to enhanced prosurvival pathways have been considered contributory to disease flare at ibrutinib discontinuation [28]. Only half of patients who experienced flare during a hold in the current study had BTK/PLCG2 mutational testing performed; however, two thirds with testing lacked a resistance mutation. Further investigation is needed to better understand the reversal of ibrutinib‐induced changes in cellular crosstalk [29, 30] and T‐cell populations [31] when treatment is withdrawn temporarily. Clinical correlation with the CLL secretome or immunoregulatory cell profiles may elucidate aspects that result in the ibrutinib‐addicted phenotype and guide management of these patients.

Limitations secondary to the retrospective nature of the study include the likelihood that additional interruptions in therapy occurred but may not have been recorded in the medical record. Similarly, the reliance on the degree of documentation and the nonuniform evaluation of patients at the time of disease flare may have led to events being characterized as mild when in fact they would have qualified as severe had additional details been available or evaluations performed. Although there is inherent complexity due to overlapping symptoms between this phenomenon and the natural course of progressive disease in CLL, the majority of patients being without evidence of disease progression at the time of hold reduced the impact of this factor. Lastly, the distinction between mild and severe cases of disease flare was arbitrarily defined and needs external validation.

Conclusion

Our study shows that temporary interruptions in ibrutinib therapy in patients with CLL are common, with more than one third of patients holding ibrutinib at least once during the course of their treatment. One out of four patients who had at least one treatment hold experienced a flare of disease, which was ameliorated with the reintroduction of ibrutinib. Although the occurrence of disease flare did not adversely impact OS, the associated morbidity of these events and observation of shorter EFS and time to next treatment warrant additional consideration. It is critical for practicing hematologists and oncologists to be aware of the potential for this phenomenon during even transitory periods of treatment discontinuity, and further investigation into predictive factors and methods to mitigate risk are needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia on September 20, 2019. The conduct of this research was supported in part by the Henry J. Predolin Foundation. S.A.P. and S.S.K. also acknowledge support from the Mayo Clinic K2R Career Development Program.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Paul J. Hampel, Timothy G. Call, Kari G. Rabe, Wei Ding, Sameer A. Parikh

Provision of study material or patients: Timothy G. Call, Wei Ding, Eli Muchtar, Saad S. Kenderian, Yucai Wang, Jose F. Leis, Thomas E. Witzig, Amber B. Koehler, Amie L. Fonder, Daniel L. Van Dyke, Esteban Braggio, Neil E. Kay, Sameer A. Parikh

Collection and/or assembly of data: Paul J. Hampel, Kari G. Rabe, Susan M. Schwager

Data analysis and interpretation: Paul J. Hampel, Kari G. Rabe, Susan L. Slager, Sameer A. Parikh

Manuscript writing: Paul J. Hampel, Timothy G. Call, Kari G. Rabe, Wei Ding, Eli Muchtar, Saad S. Kenderian, Yucai Wang, Jose F. Leis, Thomas E. Witzig, Amber B. Koehler, Amie L. Fonder, Susan M. Schwager, Daniel L. Van Dyke, Esteban Braggio, Susan L. Slager, Neil E. Kay, Sameer A. Parikh

Final approval of manuscript: Paul J. Hampel, Timothy G. Call, Kari G. Rabe, Wei Ding, Eli Muchtar, Saad S. Kenderian, Yucai Wang, Jose F. Leis, Thomas E. Witzig, Amber B. Koehler, Amie L. Fonder, Susan M. Schwager, Daniel L. Van Dyke, Esteban Braggio, Susan L. Slager, Neil E. Kay, Sameer A. Parikh

Disclosures

Wei Ding: Merck (RF); Saad S. Kenderian: Novartis, Humanigen, Kite, Gilead, Juno, Celgene, Tolero, Lentigen, MorphoSys, Sunesis (RF), Novartis, Humanigen, Mettaforge (IP), Humanigen, Kite, Juno (SAB); Thomas E. Witzig: Acerta, Spectrum, Celgene (RF), Incyte, Seattle Genetics, AbbVie, MorphoSys, Spectrum, Immune Design; Neil E. Kay: Acerta Pharma, MEI Pharma, Pharmacyclics, Tolero (RF), Pharmacyclics, Tolero, Acerta, AstraZeneca, Cytomx Therapeutics, Dava Pharmaceuticals, Juno (SAB); Sameer A. Parikh: Pharmacyclics, MorphoSys, Janssen, AstraZeneca, TG Therapeutics, Celgene, AbbVie, Ascentage Pharma (RF), Pharmacyclics, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Verastem Oncology (SAB). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

Author notes

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.