One of the most important challenges in the field of learning is to improve learning processes to allow an increasingly rapid acquisition of concepts and information - with the least effort possible - and the integration of this information into a general evolutionary process and flourishing of personal resources that involves various levels - the cognitive, the emotional and the relational - of the individual.

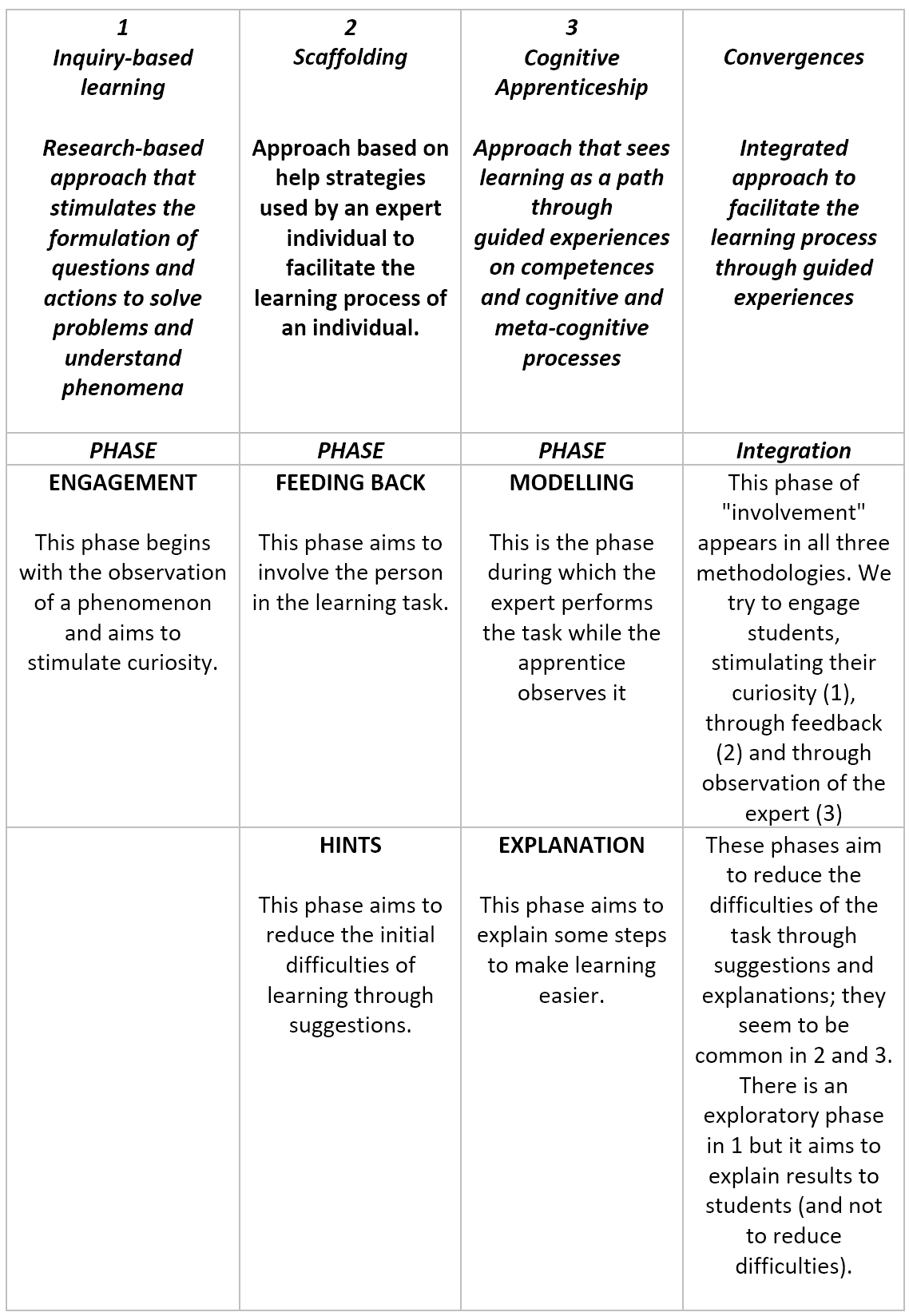

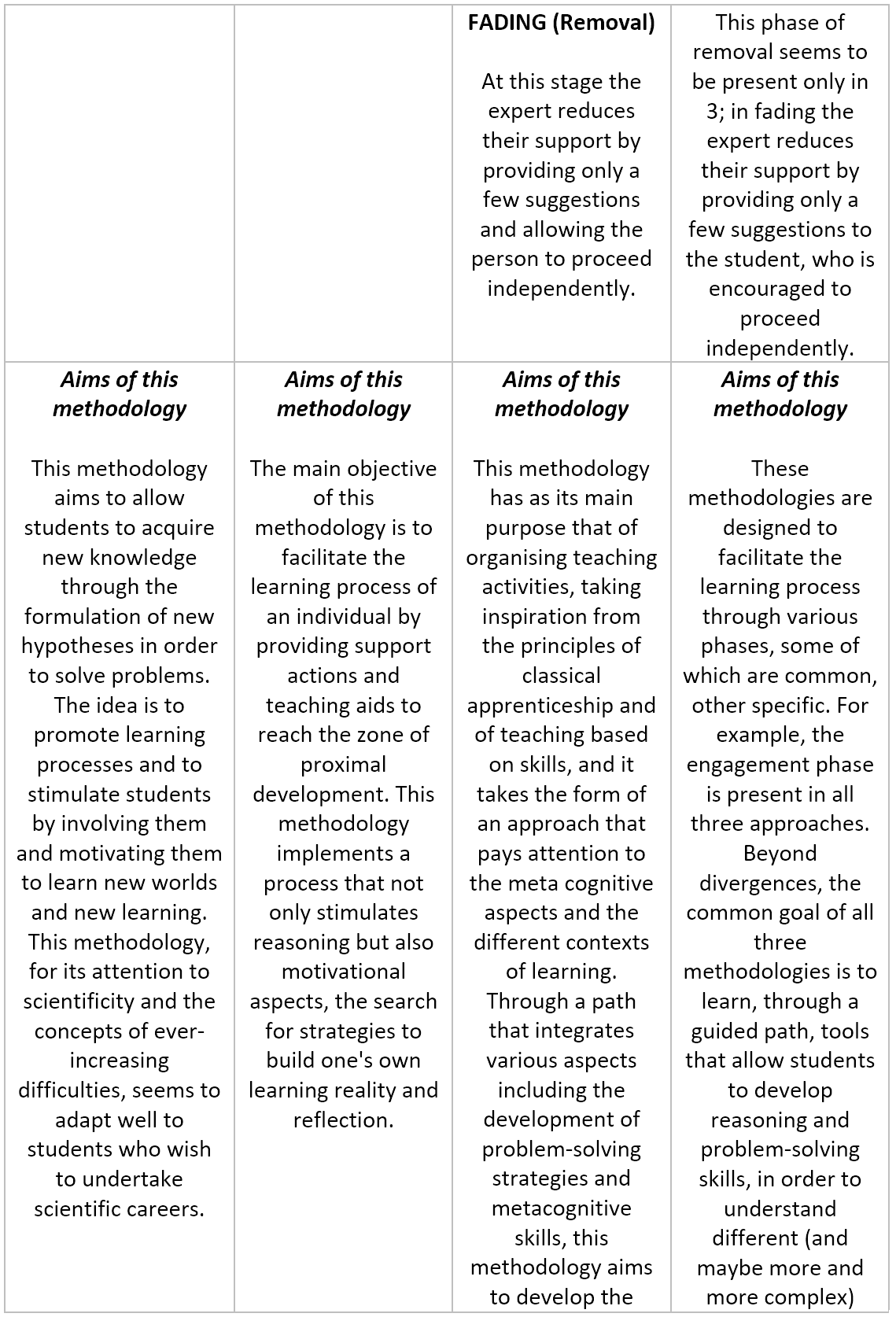

When discussing these aspects, it is firstly necessary to pay attention to existing current methodologies and to the way in which terminologies such as Scaffolding, Mentoring, Coaching, Inquiry-Based Learning and Cognitive Apprenticeship are used. The basic problem already raised in literature is that there is no standard taxonomy or a shared classification of these methods (Dennen, 2004). For example, some authors refer to mentoring or coaching as a form of scaffolding (McLoughlin, 2002), others refer to scaffolding as an aspect of coaching (Collins, Brown, & Newman, 1989) and others still prefer to see these aspects as separate strategies that fall under the classification of cognitive apprenticeship (Dennen, 2004; Enkenberg, 2001; Jarvela, 1995). Only after trying to better clarify how these learning strategies differentiate from one another, will it be possible to understand their functions and analyse their differences, in order to hypothesise a new model of inclusive learning, on a relational basis, methodologically enhanced in the richness of the integrated perspective.

This study aims to position learning processes in an interpersonal and intrapersonal, relational inclusive key and to analyse and integrate the common factors of the three main learning methodologies (Scaffolding; Cognitive Apprenticeship; Inquiry-Based Learning). The prospect of the new integrated learning model will be enriched with some indispensable components for improving cognitive stimulation, sensitivity towards learning processes, integration and positioning of new acquisitions within the developmental process, and the cognitive, emotional and relational flourishing process of the involved participants.

This new learning model has been generated from a different perspective compared to previous models. Its relational framework, which is integrated and inclusive in relation to the methodologies, encourages a "mirror" type learning mode, which in turn through greater awareness (feedback and psychological mindedness circuits) can facilitate the achievement of Zones of Proximal Development (ZPD) and allow an easier transformation of skills into competences as tools for achieving learning in later development areas (belonging to other domains), enabling integration of cognitive, emotional and relational levels.

Description of the three methodologies subject to this study

Scaffolding

The term "Scaffolding" indicates a set of aid strategies used by an expert individual to facilitate the learning process of an individual. Bruner (1976) was the first to use this term to indicate the metaphor of the intervention of a skilled person (tutor) who helps a less experienced person (child/youth) in solving a problem that they alone would not be able to complete.

In the field of education, Scaffolding represents a metaphor about a structure that is realised to help students achieve their goals and is gradually removed when the person no longer needs it; this concept is very similar to a physical scaffold placed around a building under construction, which is removed progressively as the building approaches completion.

The teacher operates a mediation activity (scaffolding) and students are supported by this mediation while operating at a level slightly than the limits of their development area (zone of proximal development). The help of the teacher (or a more experienced companion) provided to students in their zone of proximal development is called scaffolding.

Scaffolding can present itself and be put into effect in various ways, even if generally a teacher begins to offer students the contents of learning in an appropriate manner adequate to their school (developmental) level of reference and then, at a later time, begins to present a problem by expressing verbally the path needed to arrive at the solution. This learning process combines actions, images and language.

After this phase, in a subsequent session, this process is generally repeated a couple of times, asking stimulus questions to the students who are invited to respond. Obviously every answer, right or wrong, receives positive feedback from the teacher, just to encourage constructive participation in didactic activities. When the student has reached an acceptable level of understanding, it is possible to propose group work to solve a new problem. In the final phase of Scaffolding, when the skills have been further consolidated, the teacher assigns new problems, and invites the students to work independently, asking for support, if necessary, from the teacher.

Cognitive apprenticeship

Cognitive apprenticeship is a didactic methodology which was developed by American researchers Collins et al. (1989), supporters of the social constructivism theory. Apprenticeship is an intrinsically social method of learning that is generated with the intent of helping novices to become experts in different fields such as mechanics, construction, obstetrics, and the legal field.

At the centre of apprenticeship is the figure of the expert who assists less experienced people, providing support, also with practical examples, to aid in the attainment of objectives. Traditionally, apprenticeship has been associated with learning in commercial or artisan contexts; however, this concept has also taken place in the field of learning.

Cognitive apprenticeship refers, in some respects, to the concepts expressed by Vygotsky, to internalisation and to the zone of proximal development, concepts that indicate how relevant interaction with others and help are in an individual’s learning process. It takes the form of an approach that pays greater attention to metacognitive aspects and to the different contexts of application of the learning process. Collins et al. (1989, p. 456) synthetically define cognitive apprenticeship as "learning through guided experiences on competences and cognitive and metacognitive processes". Two fundamental concepts of this procedure are that of positioning and legitimate peripheral participation (Dennen, 2004; Lave & Wenger, 1991).

Positioning in learning takes place through active participation in an authentic setting, based on the belief that this commitment promotes learning much more than traditional systems; this is more than learning by doing because it is a kind of learning that requires deeper rootedness in an authentic context. Learning in cognitive apprenticeship takes place through legitimate peripheral participation, a process in which newcomers are placed in the periphery and gradually moved towards full participation. This is not a real technique or a strategy, as it tends to happen naturally on its own. Legitimate peripheral participation is perhaps easier to understand through an example of work apprenticeship. Essentially, apprentices learn to know both the general process of the broader task and the profession, and criteria for evaluating performance through the completion of small tasks. Later, as people gain experience, more complex and meaningful tasks to complete are presented to them.

Regarding cognitive apprenticeship Collins et al. (1989) developed six methods to be applied during the different stages of the process:

- the first three (modelling, coaching, scaffolding) are the focus of the apprenticeship and are linked to the cognitive and metacognitive area;

- the next two (articulation and reflection) are developed in order to encourage problem-solving techniques;

- the last step (exploration) is designed to help lead apprentices to independence and to help them identify and solve potential problems.

Inquiry-Based Learning approach

The Inquiry-based approach (Inquiry-based learning in US education or Inquiry-based science education in its European interpretation) was recently promoted by the European Commission also in secondary schools (Rocard Report 2007) and envisages a very different sequence of phases compared to the usual ways of delivering learning. In literature several proposals are found for the application of this approach; for simplicity the one proposed by the BSCS, also known as the "5E Model", is adopted.

The activity consists of the following phases:

ENGAGEMENT

The activity always begins with the observation of a phenomenon that can be framed within the themes of the didactic module, on which the students are invited to investigate interesting aspects and ask questions. At this stage the students are free to express their opinions and observations and it will be the teacher's task to collect the most significant ones for the module.

This phase has the task of attracting attention, stimulating curiosity and inducing in the student the feeling of "wanting to know more". It is the most important phase, because the success of the whole learning path derives from its proper organisation.

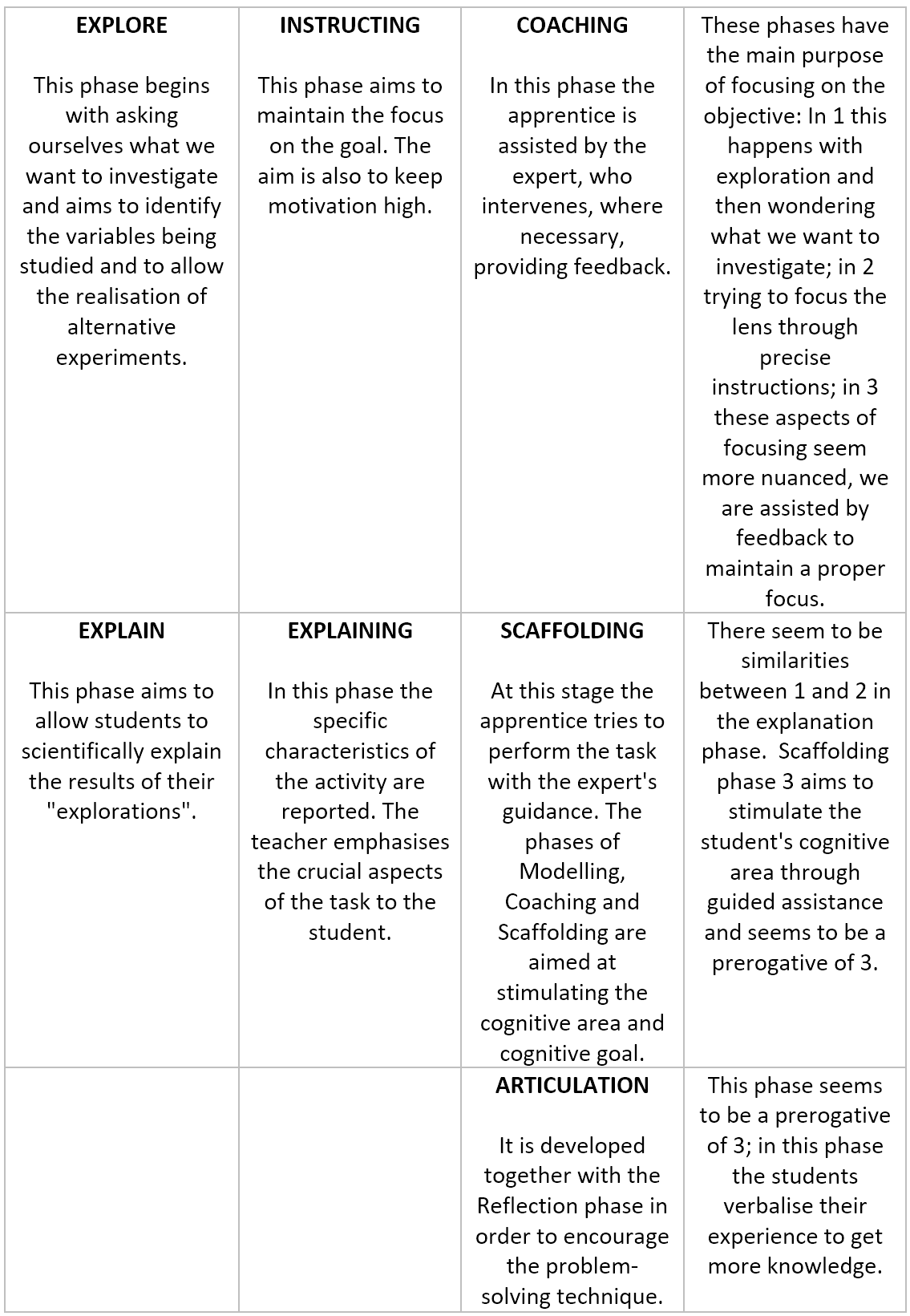

EXPLORE

In this phase, once the questions are collected on what students want to investigate, they are directed towards the experimental phase, first by asking them to design a laboratory experiment that can provide answers. The teacher must be ready to receive suggestions or possible proposals from students who wish to experiment with the phenomenon in a different way, adding these proposals to those of the module (by carrying out alternative experiments with teachers, or at home).

The experimental activity will be flanked by data collection. It is essential that students identify the variables involved and experiment them one at a time. In this phase, therefore, they must record data, isolate variables, create graphs, interpret results, develop hypotheses and organise their findings.

EXPLAIN

Students are introduced to models, laws and theories. Correct vocabulary is provided, which allows them to explain the results of their explorations in a rigorously scientific way, stimulating autonomous research on the studied context.

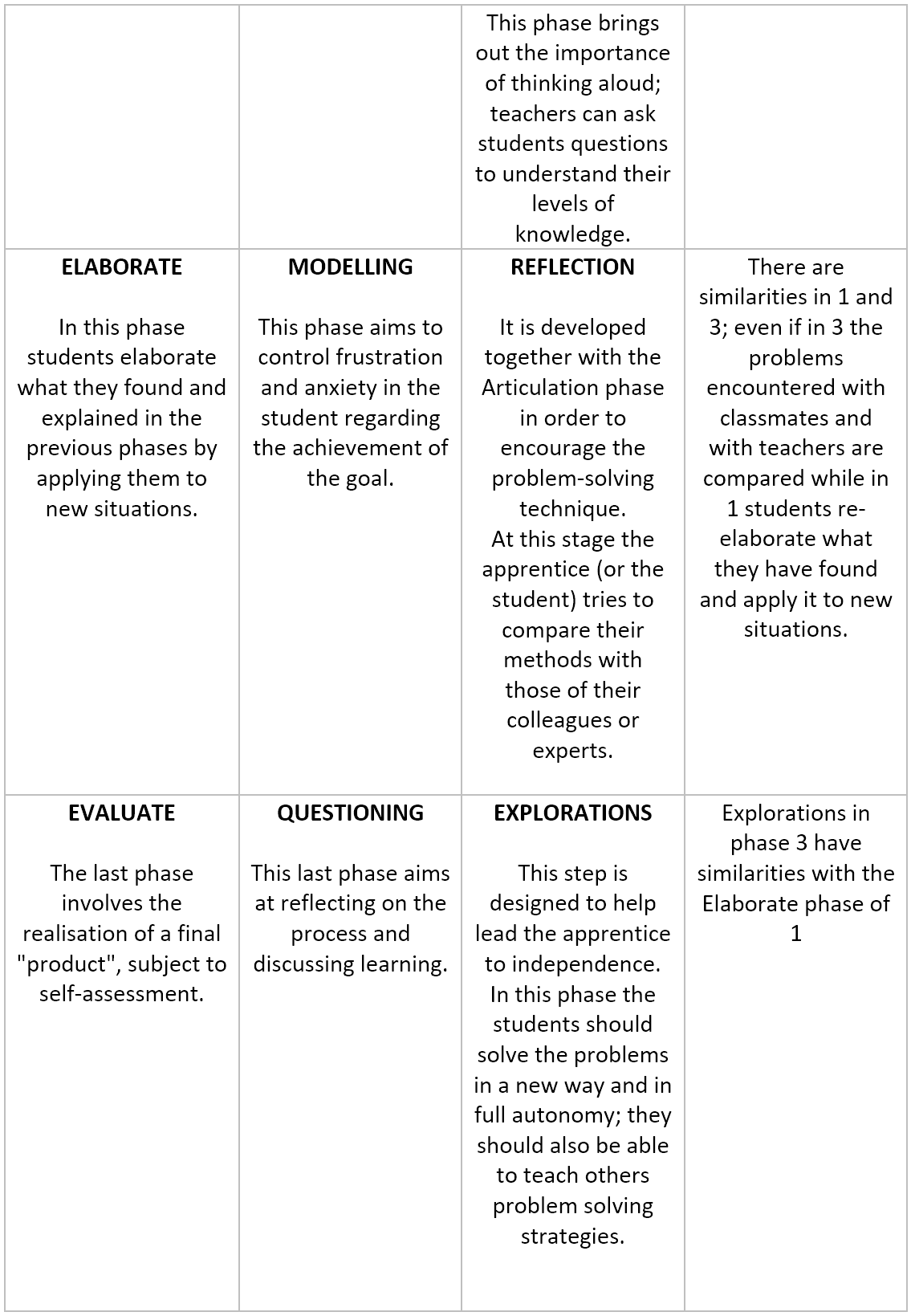

ELABORATE

In this phase the students elaborate what they found and explained in the previous phases, applying it to new situations, which can bring out other questions and hypotheses to be explored. Students should achieve "transfer of learning"; therefore further ideas will be proposed (images, videos, etc.).

EVALUATE

The last phase involves the creation of a final "product", which is assessed both in a formative and summative way, in other words an authentic assessment (a concept that is also taken up by other "currents" of studies related to learning). Evaluation can be included in each phase, going beyond that of the learned notions. Students should be made aware of the fact that at every stage there will be evaluation, so as to guide the actions of the individual and the working group. This assessment can take the shape of a self-assessment, evaluation by the members of the group and evaluation by the teacher. The final product can be discussed in various ways: in front of the teachers and the researchers, on a special occasion, framed on a Science Day, in an exhibition or other.

The phases envisaged by Inquiry-based learning are not to be considered obligatorily consecutive, but they can intersect in various ways.

For example, data collection can take place in the ENGAGEMENT phase, as indeed, new events may emerge during the EXPLORE phase, with further discussion points, identification of new problems and the formulation of new questions.

Towards a new integrated inclusive relational methodology: “Relational Based Inclusive Learning Methodology (RBILM)”

Introduction

On the basis of the research carried out on the theme of learning and shared experiences of teachers and students, and after a careful theoretical-practical re-elaboration, it was possible to hypothesise a new integrated and inclusive methodological model, which takes into account the factors common to the different approaches of learning so far described and recontextualises them in a new dimension, through an integrated lens on relational bases.

Reading situations through a relational lens mainly means attributing a priority value, a privileged channel, a founding dimension of learning to the relationship between individuals, in this case between teacher and student (and between students). In other words, it means encouraging learning in a specific context, taking a relational frame as reference.

Usually teacher-student relationships are characterised by asymmetry and the professor or teacher often tend to embody the role of master; the cognitive development of the person is often facilitated as a preferential channel, tending to overlook the student's emotional and relational aspects, as they are considered not the focus of the teaching-learning process and only marginally involved in the learning process.

The relational perspective that is emphasised here, instead, starts from the assumption that relational dynamics contribute decisively to the process of learning and to the development of the individual, also allowing for a more conscious and mature integration of the material learned, from a developmental point of view and one that leads to a more satisfactory flourishing of resources.

In other words, the relational perspective applied to learning can contribute to a faster (and simplified) acquisition of information and therefore to a faster achievement of the zone of proximal development, an easier adaptation of learning made, combined with a greater awareness of the learning itself, thus facilitating a recall of learning. Furthermore, this perspective appears to facilitate the transformation of the learned competences into useful tools for learning concepts belonging to higher domains, allowing integration of competences and at the same time a more rapid process of evolution.

One of the presuppositions of this new theoretical formulation is that of re-dimensioning a spirit of division between teacher and student and highlighting the role of shared experience. According to this approach, teacher and student would influence each other in the interpersonal field and would influence the mode of learning. Thus, encouraging an understanding of the relational dynamics between teacher and student and of the weight of methodological choices even in relational processes in order to lead students to a more conscious, more shared and more effective way of learning.

An Integrated and Inclusive Methodology

The Relational-Based Inclusive Learning Methodology (RBILM) shares with other methodologies almost all the aspects rooting them in the relational dimension. This new integrated methodology is configured as a meta-model that absorbs the basic assumptions of the three previously cited methodologies and shares their techniques, focusing however, unlike the three methodologies, on the individual as a whole from a human point of view, in the first place, and then in its cognitive, emotional and relational aspects. In this training meta-model, the individual with their demands has the priority rather than the mere learning. Teachers need to tune in to the student's developmental world and their potential for flourishing in order to better understand their levels of development and therefore be able to guarantee tailored learning.

Focus on the individual

In this new theoretical synthesis the main focus appears on the individual as a whole with their wealth of knowledge, their processes, their learning times and their characteristics and systems. This allows us to favour individual differences and to encourage them, and not to provide the same way of learning for everyone.

Focus on emotional aspects

Also the emotional component is inserted and considered in this approach; asking students what they felt when they were able to complete a task, or when they failed, is important and useful in order to stimulate them in the right direction. The emotional aspect can also be analysed to encourage communication and therefore an improvement in the relationship between student and teacher.

Focus on cognitive aspects

Cognitive functioning changes day by day thanks to apprenticeships, which consist of training and assistance from the expert (coaching); continuous support and help through indications and feedback (scaffolding); a gradual reduction of assistance (fading) as the apprentice becomes more competent in articulating what they are doing and in talking about the experience of which they have become aware; thoughtful reflection on their performances and comparison of these with those of their peers or of experts, a comparison that enhances self-correction and self-regulation skills; finally, exploring and solving problems in an autonomous way, choosing new paths and solutions (Collins, Brown & Newman, 1995; Pontecorvo, 2000).

Focus on relational aspects

The focus of this meta-model involves attributing a fundamental value to the relationship between individuals, in this case between teacher and student (and between students), to allow the opening of a privileged channel to promote learning. This can concretely be achieved through feedback circuits that interchange with each other.

Feedback circuits (teacher-student, student-teacher, student-group, group-student, group-teacher, teacher-group). Feedback circuits in this theoretical-applicative model (RBILM) form a real network that allows a self-other evaluation, which is fundamental in the learning process.

STAGES of Relational-Based Learning (RBL)

Active involvement phase (feedback): this phase aims to integrate the Engagement phases of Inquiry-based learning (IBL), Scaffolding Feeding back (Scaff) and Cognitive Apprenticeship (CA) Modelling. All these phases of the three methodologies mentioned are aimed at stimulating curiosity and involving the person in the learning process.

Modelling/Explanation phase (feedback): this phase aims to integrate the phases of Scaff's Hints and CA's Explanation. The common goal of these phases is to explain certain steps and make learning easier.

Active Research phase (Education/Training) (feedback): this phase aims to integrate those of IBL Explore, Scaff Instructing and CA Coaching. The common objective is to assist the person in active research.

Problem-Solving phase (articulation, reflection) (feedback): this phase aims to integrate the Explain phases of IBL, Scaff Explaining and Scaffolding (Assistance) and CA Articulation. A common goal in these phases is to encourage stimulation through explanation.

Reflection Phase (Exploration, Evaluation) (feedback): this phase aims to integrate some aspects of the elaborated phases of IBL, of Scaff Modelling and of CA Reflection. A common goal seems to be that of re-elaboration.

Accompaniment Phase (Fading) (feedback): this phase aims to integrate the Evaluate phases of IBL, of Scaff Questioning and of Explorations and Fading of CA. The common objective of these phases seems to be to facilitate the independence of the subject.

Conclusions

The new integrated learning methodology "Relational-Based Inclusive Learning Methodology (RBILM)" is set up as a response to the challenges that the 21st century poses. In the current context, characterised by insecurity and continuous change typical of liquid societies (Bauman, 2000), and marked by a constant acceleration of the pace of life of modern society (Rosa, 2015), this new learning methodology has the objective of allowing an ever faster acquisition of concepts and information by enhancing the construction of the area of forces, autonomy and self-determination of students. The facilitation lies in the implementation of a general developmental process in which the construction of personal strength allows individuals to plan and implement in an autonomous and responsible way their own path of development within the dynamic, complex and tumultuous reality of the 21st century. The new inclusive and integrated methodology of learning with the involvement of different levels (cognitive, emotional, relational) will allow the flourishing of personal resources for full realisation of individual talents within the complexity of post-modern society.

METHODOLOGICAL SCALE “Common factors of learning”

Bibliography

Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In L. B. Resnick (Ed.), Knowing, learning, and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glaser (pp. 453-494). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (1995). L’apprendistato cognitivo. Per insegnare a leggere, scrivere e far di conto. In C. Pontecorvo, A. M., Ajello, & C. Zucchermaglio, I contesti sociali dell’apprendimento. Acquisire conoscenze a scuola, nel lavoro, nella vita quotidiana, (pp. 181-231). Milano: LED.

Dennen, V. P. (2004). Cognitive apprenticeship in educational practice: Research on scaffolding, modeling, mentoring, and coaching as instructional strategies. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (2nd ed.) (pp. 813-828). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Enkenberg, J. (2001). Instructional design and emerging models in higher education. Computers in Human Behavior, 17, 495-506.

Jarvela, S. (1995). The cognitive apprenticeship model in a technologically rich learning environment: Interpreting the learning interaction. Learning and Instruction, 5, 237-259.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McLoughlin, C. (2002). Learner support in distance and networked learning environments: Ten dimensions for successful design. Distance Education, 23(2), 149-162.

Pontecorvo, C. (2000). Manuale di psicologia dell'educazione. Bologna: il Mulino.

Rapporto Rocard (2007). Science education now: A renewed pedagogy for the future of Europe. European Commission. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/research/science society/document_library/pdf_06/report-rocard-on-science-education_en.pdf

Rosa, H. (2015). Accelerazione e alienazione. Per una teoria critica del tempo nella tarda modernità (Trad. it. E. Leonzio). Torino: Einaudi.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 17(2), 89-100.